By the winter of 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic sounded like a broken heartbeat.

Convoys vanished off the map in a burst of static. Merchant ships went silent in the middle of a sentence. Men died without anyone on shore realizing they’d needed help until the sea sent their lifeboats back empty.

German U-boats prowled the shipping lanes like patient sharks. The Allies had radar sets, high-frequency direction finding, new tactics and new ships—but all of it depended on one simple, fragile thing:

The lines had to stay alive.

Inside a low brick building on the Liverpool waterfront, in a room full of humming relay racks and ink-stained charts, one of those lines flickered.

And a woman in a WRNS uniform heard it as clearly as if it were her own pulse going weak.

Eleanor “Ellie” Hart had grown up with the sound of static.

As a girl in the late twenties, tucked away in the back of her father’s shed behind a row of terraced houses, she’d learned to love the crackle and hiss of broken radios. Old sets ended up there the way stray cats did. Neighbors who couldn’t afford repairs dropped them off. “Maybe Mr. Hart can coax one more song out of it,” they’d say.

Her father did his best—wires twisted, valves swapped, solder applied in careful beads. But it was the day he slid a stubborn set aside and muttered, “You have a go, El,” that changed everything.

She was ten. Her hands were small, nimble. She knew nothing of Ohm’s law and voltage, but she understood puzzles, and she understood listening. She leaned in close, nose almost touching the dusty chassis, inhaled that peculiar smell of hot dust and old insulation, and heard…a hum.

Something in there wanted to work.

She followed the hum the way other kids followed music. She prodded, twisted, traced where the sound grew stronger and where it disappeared. When she finally spotted a tiny break in a coil of wire and soldered it back together—her first ugly blob of metal—she held her breath and flipped the switch.

The set crackled, whined, then found a station.

Her father laughed. “Looks like I’ve been demoted,” he said, pride hiding in the corner of his mouth. “You fix ’em now. I’ll make the tea.”

By 1940, the tea and the radios were both a lot more serious.

Germany’s warplanes had found Liverpool. The docks that had once smelled of fruit and wool and oil now reeked of smoke and the ghosts of burned ships. Convoys from America and Canada poured into the port—grain, tanks, men—and Nazi bombers did everything they could to choke that lifeline.

When the call came for women to join the Women’s Royal Naval Service—the Wrens—most of Ellie’s friends went into clerical posts. Typing. Filing. Answering telephones.

Ellie took one look at the recruiting forms and handed over her grease-stained references from a radio repair shop instead.

“I’d like wiring work,” she said matter-of-factly.

The petty officer behind the desk raised an eyebrow. Then he looked at the papers again, at the neat handwriting, at the list of sets serviced and courses passed.

“Wiring, is it?” he said. “We’ll see what the Admiralty says.”

The Admiralty, as it turned out, said yes.

Not loudly. Not publicly. But somewhere in the machinery of the Royal Navy’s engineering corps, a checkbox was ticked that allowed a twenty-seven-year-old woman with a quiet voice and steady hands into rooms normally reserved for men.

Those rooms were the nerve centers of a global war.

If the front lines were ships and guns and torpedoes, Ellie’s front line was copper. Coax. Switches. Codebooks. The jungle of cables that ran between Admiralty House in London, coastal command posts, escort group flagships and American convoys.

“Signals are the bloodstream,” her first supervisor told her on a wet autumn morning, flinging open the door to the relay room in Liverpool. “Ships are the fists. You keep the blood moving, Hart, or the fists don’t land.”

Rows of relay racks filled the narrow space, humming and chattering like a metallic forest. On the far wall, a row of operators sat with headsets on, jotting down coded messages as they came in, sending others out with practiced rhythm.

Ellie stepped into that world like she’d stepped into her father’s shed years before—with a sense of recognition.

The logic of it made sense to her. If this line failed, that coil overheated. If that relay stuck, this signal never reached the switchboard. Every part touched every other part. You couldn’t treat any wire as “just a wire.” It either carried life, or it didn’t.

Her title was humble: engineering rating, communications branch. Her pay was modest. Her reports went up the chain under the signatures of male officers who made corrections in red ink without really understanding what she’d done.

She didn’t care.

The first time a convoy arrived early because a weather warning she’d helped route around a faulty junction got through in time, she stood on the dock in the drizzle and watched men walk down gangplanks alive who might have been names on a list.

That was enough.

Every working line was a lifeline. Every hum in her headset was a heartbeat.

So when the hum stopped, she felt it viscerally.

And on one freezing night in December 1942, it nearly stopped for good.

The storm came in off the Irish Sea like a living thing.

By midnight, rain hammered the windows of the Liverpool base hard enough to blow in around the frames. Wind yanked at the blackout curtains. Somewhere out in the dark, sirens wailed half-heartedly, then died, drowned by the gale.

Inside the relay building, the air was hot and dry despite the weather, heated by lamps and equipment that never slept. Cigarette smoke curled toward the ceiling. The relay racks rattled and clicked, their coils and contacts running like a thousand tiny hearts.

Ellie sat on a tall stool, sleeves rolled up, a pencil tucked behind her ear. A wiring diagram lay open on the bench in front of her, its lines and symbols more familiar than London streets.

She heard the shift in sound before the alarm went.

The chorus of hums and clicks had a rhythm you could get used to. When a line dropped briefly, there was a hiccup, then recovery. When an operator mis-plugged a patch cord, there was a thin squeal until someone corrected it.

This was different.

Somewhere behind the racks, under the normal chatter, a low whine built and then flattened—like a note held too long on a violin string, then cut.

The red alarm light over the main status board started to flash, throwing garish pulses across the walls.

The duty officer, a thin lieutenant with permanent worry lines etched between his brows, lunged for the panel.

“Transatlantic trunk three down!” he shouted. “Repeat, three is down!”

The room, usually a model of controlled noise, lurched toward chaos.

Operators ripped off their headsets, shouting over one another.

“I’ve lost Halifax!”

“Convoy ONS-92 just went dead mid-report, sir!”

“Nothing on backup four—she’s flat as a pancake!”

Ellie slid off the stool, heart pounding.

Transatlantic trunk three was not just another line. It was one of the main cables carrying high-priority traffic between the British command and Allied forces on the far side of the ocean. Merchant convoys, escort group deployments, U-boat sighting reports—all of it pulsed through trunk three in bursts of Morse and voice.

If it stayed dead, they didn’t just lose a phone call.

They lost a grip on hundreds of ships.

“Locations?” the lieutenant demanded. “Give me positions.”

An operator slapped a chart onto the table. Red pencil marks dotted the Atlantic.

“There,” he said, jabbing. “Convoy HX-219. Five hundred ships, give or take. They’re about to hit the gap, sir.”

The gap.

That terrible stretch in the middle of the Atlantic where land-based air cover disappeared and U-boats hunted in packs, surfacing under the cover of darkness and storm.

Those five hundred ships weren’t alone—destroyers and corvettes and sloops escorted them—but the escorts needed information. Routing changes. Intelligence updates. Air cover coordination. Without a working line, the convoy was a blind giant, lumbering into a minefield.

“Has anyone checked the coastal repeater?” the lieutenant barked.

“Already on it,” another tech called from the far side of the room, headset clamped to one ear. “Line’s good to Holyhead. The fault’s somewhere between here and there on the main run—no visible breaks reported.”

“Could be sabotage,” someone muttered.

“Could be the bloody weather,” someone else snapped.

Ellie didn’t say anything. She moved.

She strode down the narrow aisle between the racks, gently but firmly shouldering aside two younger ratings who were already yanking patch cords and testing outlets at random.

“Stop pulling things blindly,” she said. “You’ll make it worse.”

“We have to find the fault, Hart!” one protested, his voice sharpened by fear.

“Yes,” she said calmly. “And we will. But not by thrashing.”

The status board over the main trunk rack showed trunk three as a column of dead red.

She closed her eyes for a second, mentally tracing the path. Cable from Liverpool under the Irish Sea to the relay at Holyhead. From Holyhead into the oceanic line. Into the Atlantic like a nerve stretching miles and miles through black, cold water.

They’d had damage before—anchors, storms, even enemy action. But this didn’t feel like an undersea break. If the cable had been severed, the diagnostics would show a hard fault. This was softer. Stranger.

She ducked behind the rack, into the narrow service corridor where cables ran in fat bundles along the wall like veins.

The air back there smelled different—drier, tinged with hot insulating varnish.

She ran her fingers along the cable leading to trunk three, feeling for obvious damage. Nothing. No charring. No break in the sheath.

“Check the relays!” she called.

A bank of glass-topped relay modules sat in a metal frame, each one switching its piece of the signal. The faces of most glowed a faint, healthy green, in time with the pulse of signals passing through.

One, midway down the stack, glowed wrong.

Not bright. Not dark. A faint, out-of-sync flicker. Like a candle guttering in a draft.

Ellie frowned. Her training, and a thousand hours listening to misbehaving circuits, told her that was the one.

She grabbed a hand lamp, wedged it between two racks, and leaned in, nose almost touching the coil.

The insulation looked…off. A film of dampness, darker where it had soaked into the lacquer wrapping. Humidity from the storm had snuck in around a poorly sealed vent. Over hours, maybe days, it had seeped into the coil’s innards. Under normal load, it would have been a nuisance.

On a night like this, under the strain of war-level traffic, it was poison.

Moisture plus voltage meant leakage. Leakage meant feedback. Feedback meant the signal tried to go where it shouldn’t, crossed its own path, and collapsed.

Somewhere thousands of miles away, that manifested as silence.

“The coil’s degraded,” she said, voice low, more to herself than anyone else. “We’re getting a feedback loop in the trunk. It’s blocking the whole thing.”

She straightened, wiping the back of her hand across her brow.

The solution existed in a tight, dangerous corner of her mind.

You could isolate the bad relay. Cut it out of the circuit. Re-route around it temporarily. But to do that, you had to open the frame, reach into a live system carrying enough current to knock you flat if you brushed the wrong contact. You had to cut and reconnect the heart of the main trunk while it was still beating.

“Isolate trunk three,” she called to the lieutenant. “We need to take it down at the rack.”

“We can’t take it down,” he shot back. “It’s already down.”

“I mean decouple it, sir,” she said. “So a fault here doesn’t drag the rest of the system with it.”

He hesitated. Then nodded curtly. “Do it.”

She reached for her tools—a small canvas roll of pliers, screwdrivers, and a soldering iron, the handle worn smooth where her hand normally gripped it.

Just as she unrolled it on the floor, the door banged open.

Spray and cold air rushed in along with a man in a wet greatcoat.

Commander Hughes, communications division. Ellie recognized his voice before she saw his face—that clipped public-school accent, the one that could sound amused or furious or both.

“What the devil is going on in here?” he demanded, shaking water from his cap.

“Transatlantic trunk three is down, sir,” the lieutenant said. “Hart’s found a fault in the main rack. She thinks she can patch it.”

Hughes strode over, peered at the glowing relay, then at the bundle of tools on the floor.

“You propose to work on a live trunk line?” he asked Ellie.

“Yes, sir,” she said. “If we re-route the current around that coil, we can restore function long enough to—”

“Stand down, Hart,” he snapped. “We’ll wait for command approval.”

She blinked.

“With respect, sir,” she said carefully, “by the time we get approval, that convoy will be in U-boat waters with no guidance. We have to act now.”

Hughes’ jaw tightened. Outside, thunder growled.

“If you fail,” he said, “you don’t just electrocute yourself and burn out one coil. You take down this entire facility. We lose every trunk for hours, perhaps days. We have protocols for a reason.”

Ellie felt the weight of thirty terrified men in the room pivot toward her and then back to him. The air soured with fear.

She could picture the memo trail already: unauthorized action, damage, court-martial. Woman oversteps. Woman fails. We should have kept them in the typing pool.

She swallowed.

“Sir,” she said, more quietly. “We already have failure. That line is dead. We are blind to five hundred ships. The risk of doing nothing is worse.”

His eyes flashed.

“That is not your decision to make,” he said. “I will not have a rating blow my relay room to bits on a hunch. Stand down until London replies.”

He turned to the lieutenant.

“Send an encrypted priority to Whitehall,” he ordered. “Report trunk failure. Request authorization for manual intervention.”

“Yes, sir.”

He was already halfway to the door when he wheeled back toward Ellis.

“And you,” he said, “will not lay a finger on that trunk without permission. Is that understood?”

Ellie held his gaze.

“Understood, sir,” she said.

He slammed the door behind him.

The relay room fell into a thick, tense silence.

On the wall, the column of red lights for trunk three still burned steadily.

On the chart, in red pencil, five hundred ships crept toward a kill zone.

The room’s attention drifted back to her.

“Can you really fix it?” the lieutenant asked, voice low.

“Yes,” she said. She didn’t add, probably. Probably wasn’t useful here.

“How long?” someone else whispered.

“Minutes,” she answered. “If I don’t die doing it.”

The joke fell flat.

She could hear Commander Hughes’ boots in the hallway, then the muffled thud of him stomping up the stairs toward the secure room where cipher messages were sent.

Whitehall was hundreds of miles away. The priority line was good, but even if it connected, the request would join a queue of crises. Someone there would weigh the options over a cup of tea, scratch their chin, consult a protocol manual.

By then, the convoy would be in the gap.

Ellie looked at the relay again.

The coil’s faint, sickly glow seemed to pulse in time with her own blood.

She thought about her father’s shed. About the first radio she’d coaxed back to life. About the feeling of turning chaos into coherence.

She thought about the men on those ships. Some British. Some Canadian. Many American. Young farm boys from Iowa standing watch on a blacked-out deck. New Yorkers sweating over engines in the bowels of liberty ships. Texans who had never seen the ocean before the war, now surrounded by it in every direction.

They didn’t know her. Would never know her.

But right now, they were counting on a signal.

There are moments in a life when the lines—actual copper lines and the other kind, the ones inside your head—line up in one direction.

Ellie felt them all point through her, toward the relay.

“Approval can wait,” she said under her breath.

She reached for her soldering iron.

She could have asked someone to stand as a lookout. She could have whispered to the lieutenant, begged for his blessing in secret.

She didn’t.

This wasn’t about defiance for its own sake. It was about the fact that there was only room for one pair of hands back there in the rack, and she knew hers were the ones that could do it.

She flicked the power switch on the soldering iron. The tip glowed dull orange. The smell of warming flux crawled into the air.

“Shut down nonessential local circuits,” she told the nearest tech. “I want as much reserve as we can spare.”

The second-tier lines feeding local command posts flickered briefly as their relays dropped. Grumbles rose from operators at the boards; she ignored them.

The closer she got to the rack, the sharper her focus became. The rest of the room blurred into meaningless shapes and sounds. All that existed was the faintly glowing coil and the wires leading into and out of it.

She unscrewed the glass cover, carefully setting it aside.

The coil sat there, a cylinder of copper windings wrapped around a core, glistening slightly with damp. It hummed with trapped energy.

A sane person would have powered the whole frame down.

But if she did, trunk three stayed dead until they could bring the whole thing back up piece by piece.

She didn’t have that luxury.

She needed to isolate the faulty section only. That meant cutting the incoming feed and shunting it around the coil to the outgoing line—an improvised bypass, what today’s engineers would call a hack, but which to her felt like adding a new line of code to a program written in copper and magnetic fields.

Her heart hammered, but her hands were steady as she reached in with insulated pliers.

“Hart?” the lieutenant said softly behind her.

“Yes, sir?”

“If this goes wrong,” he said, “I never saw you touch it.”

She almost smiled.

“Understood, sir.”

She pinched the input wire leading into the coil, feeling its faint vibration. Then, with a quick, decisive motion, she snipped it.

For an instant, the hum in the room faltered.

She moved fast, stripping the end of the cut wire, tinning it with solder, then bringing it into contact with the outgoing terminal on the far side of the coil, effectively bridging around it.

Sparks snapped as the live current met new metal.

The smell of ozone bit into her nose. The soldering iron hissed. A tiny molten bead of metal glowed on the joint, then cooled.

She didn’t breathe.

The rack rattled.

The red light for trunk three on the panel over her head flickered.

“Come on,” she whispered. “Come on, you stubborn thing.”

For a second, it went darker.

Then it flared green.

The hum in the room swelled like lungs filling.

On the operator boards, needles jumped. Headsets crackled.

“Halifax back online!” someone shouted.

“I’ve got convoy HX-219—repeat, I have HX-219 on channel!”

“Escort group B-3 acknowledging instructions—sir, they say they never lost us, just heard a bit of static!”

The lieutenant let out a breath that sounded suspiciously like a prayer.

Ellie pulled her hands back from the rack as if she’d been leaning over the edge of a cliff and finally stepped away.

Her palms shook.

She dropped the soldering iron into its cradle, switched it off, then sat back on her heels on the floor, letting the solid weight of the earth under the building push back up through her bones.

Someone clapped her on the shoulder.

“You did it, Hart,” the tech said, voice cracking. “Bloody hell, you did it.”

She looked up at the panel.

The column for trunk three glowed healthy, steady green.

On the wall chart, an operator picked up a red pencil and shifted the little mark for HX-219 a fraction of an inch along its projected course. The line from Liverpool to those five hundred hulls had been restored.

The convoy plowed on into the night, no longer blind.

Somewhere out in the black, a U-boat captain waited at periscope depth, his hydrophones full of propeller noises. He had his own maps, his own estimates, his own hopes.

He did not know that his prey had just received new orders—zigzags to adopt, escorts to redeploy, air cover to angle in from a different direction.

He only knew, hours later, that the sea seemed emptier than it should have.

Back in Liverpool, the relay room slowly shifted from stunned elation back toward work.

There were messages to send. Logs to update. Secondary systems to bring back online.

Ellie stood, brushing dust from her skirt.

Her gloves were scorched where a stray spark had nicked them. Her fingertips felt raw with adrenaline.

“Go home, Hart,” the lieutenant said quietly. “Before Hughes comes back and turns you into a bad example.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

She picked up her tool roll, re-tied it, and slipped it under her arm.

Outside, the storm had eased. Rain still fell, but in smaller, more tired drops. The air tasted of salt and coal smoke. The docks, in the blackout, were hulking shadows.

She walked through streets pocked with bomb craters, past houses with their fronts ripped away to show wallpaper and chairs and empty beds. A milk bottle lay unbroken on a doorstep next to a pile of rubble.

Liverpool slept, or tried to.

No one stepped out onto their stoops to applaud. No one threw open a window and shouted thanks.

No one knew that in a hot room by the docks, a woman had reached into an angry coil of electricity and bent it just enough to save their sons.

She didn’t need them to know.

But as she turned her key in the lock of the small rented room she called home and leaned back against the door, fatigue washing over her, there was a tiny ache deep in her chest.

Not for a medal. Not for a speech.

Just for someone—anyone—to say, That was the right call.

She shook herself.

The radios out there were humming again. That was enough.

She slept badly, reliving the moment when the wire had sparked, half expecting to wake to someone banging on her door with an arrest order.

In the morning, the knock came.

Not an arrest.

An inquiry.

Which was, in some ways, worse.

Commander Hughes’ office looked different in daylight.

Less like the den of a predator, more like a cupboard into which too much war had been stuffed. Stacks of files. A damp overcoat hanging on a peg. A framed photograph of a woman and two children on the corner of the desk, the glass cracked from some long-ago blast.

He sat behind the desk now, cap off, hair untidy. The anger from the night before had drained away, leaving something like exhaustion in its place.

A Board of Inquiry chair from London sat beside him, a middle-aged man with the pinched look of someone used to judging paperwork more than people.

Ellie stood at attention, hands at her sides.

“Hart,” Hughes said. “We need to hear your account of the actions you took last night.”

“Yes, sir.”

She told them.

She kept it technical, as much as she could. Coil degradation. Humidity. Feedback loop. Manual bypass. She didn’t mention the picture in her head of ships in the dark, because she suspected that argument wouldn’t make it into the record.

“And did you receive authorization to alter the trunk rack?” the chairman asked, pen poised.

“No, sir,” she said. “I did not.”

“You were expressly ordered to stand down,” Hughes added, the faintest edge back in his voice.

“Yes, sir,” she said again.

“And yet you proceeded.”

She thought about lying.

But she’d spent the whole war making sure lines told the truth. It felt wrong to corrupt that now.

“Yes, sir,” she said. “I did.”

Hughes opened his mouth. The chairman raised a hand.

“Commander, allow me,” he said.

He shuffled the papers in front of him.

“The logs show the trunk went down at oh-oh twenty-four hours,” he read. “Convoy HX-219 was in mid-transmission. Your repair was completed at oh-oh thirty-two. Barely eight minutes of outage.”

“That’s correct, sir,” Ellie said.

“Subsequent reports from convoy escorts indicate that updated routing information and intelligence regarding U-boat dispositions prevented an ambush. No ships lost in the period in question.” He adjusted his spectacles. “Five hundred vessels continued without serious incident.”

“Yes, sir,” she said, though she had not known the exact details until that moment.

The chairman leaned back, looking at Hughes.

“So,” he said dryly, “it appears Rating Hart’s unauthorized action prevented a significant loss of shipping.”

Hughes exhaled through his nose.

“I am aware,” he said.

“Under normal circumstances,” the chairman went on, turning back to her, “your disobedience would be cause for disciplinary action.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

He studied her for a long moment.

“What you did was dangerous,” he said. “If you’d failed, you could have crippled this facility, cost us more in the long run, and possibly killed yourself and others.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

“You understand that.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you would do it again?”

She met his gaze.

She thought of the hum dying. Of the blank patch on the board where the convoy had been. Of the eight minutes that now stretched out behind her like a chasm she’d just barely leaped.

“Yes, sir,” she said quietly.

He nodded once, as if he’d expected no other answer.

He capped his pen.

“The Admiralty is issuing a memorandum,” he said, flipping the top sheet around so she could see the heading. “It will note that an unnamed engineer undertook an unsanctioned but essential repair under extraordinary circumstances, resulting in the preservation of convoy communications. For operational security, your name will not be attached.”

So that was that.

No court-martial.

No commendation.

Just a line in a secret file that would sit in a cabinet somewhere in London, gathering dust.

“You will be transferred,” Hughes added, his shoulders slumping slightly. “Different station. Fresh start. Less temptation to…improvise.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

Anger flared in her, hot and bright. Not at the transfer. Transfers were part of the war. At the fact that the line in the report that would mention what she’d done would not have her name on it.

Her reports had been signed for her since the first day she’d walked into a relay room.

She’d told herself it didn’t matter.

Now, for the first time, she wondered if that had been entirely true.

She swallowed it down. War didn’t care about your feelings. Wires didn’t care who fixed them.

“Dismissed,” Hughes said.

She saluted, turned, and left.

Outside, the relay room hummed on.

Operators leaned over their boards, pencils scratching. The status panel glowed reassuring green. Somewhere out in the Atlantic, men drank bad coffee and cursed the cold, unaware that their voices were now traveling along a slightly different path through the machinery to reach home.

Ellie walked back to her station one last time.

A younger rating, newly arrived, glanced up at her.

“Did you hear about the ghost?” he asked excitedly, clearly unable to keep the story to himself. “Some phantom engineer who fixed the Atlantic trunk in eight minutes flat. They say the whole place was about to blow, and she—or he, I guess—just reached in and sorted it.”

She looked at him.

“Is that so?” she said.

He nodded vigorously. “They don’t know who it was. Just that it had to be a ghost. Or an angel.”

“Or someone who’d done their homework,” she muttered.

He didn’t hear.

She sat on her stool, unfolded a clean wiring diagram, and picked up her pencil.

“Every signal is a heartbeat,” she wrote in the margin, almost without realizing it. “Keep it alive.”

The war did not slow down because Ellie had saved a convoy.

U-boats kept prowling. Bombers kept flying. New technologies—proximity fuses, better sonar, even crude early computers—shouldered their way into the relay rooms.

Ellie went wherever the Admiralty sent her.

Belfast. Glasgow. A small anonymous station on the coast of Wales where the sea beat against the cliff outside so loudly that sometimes it drowned out the machines.

Her reputation moved with her, but only in whispers.

“Ask Hart,” people would say when a problem refused to yield. “She has a way with lines.”

Sometimes, when a particularly knotty fault surrendered, someone would grin and call her “the ghost.”

She never flinched. She never told them why the nickname fit.

Years of overnight shifts and equipment noise took their toll.

Her hearing developed a permanent fuzzy edge, a ring that never quite went away. The hand that held the soldering iron developed a tremor if she skipped meals or slept too little. She became adept at hiding both.

By 1944, the Admiralty decided they needed her more as a teacher than as a miracle worker.

“Time to make more of you,” a commander told her, trying to sound light about it. “We can’t keep relying on one ghost in every crisis.”

She was posted to a training facility, a nondescript building on the outskirts of Portsmouth.

There, in classrooms that smelled of chalk and oil, she stood in front of rows of fresh-faced ratings—men and women—and drew circuits on the board.

“This is not wires and metal,” she told them, tapping the diagram where the trunk lines met the relays. “This is blood and bone. Every connection that fails is a ship not warned, a man not called back from the dead. You will not treat any wire as trivial.”

She demonstrated proper safety procedures with ruthless precision.

“You do not touch a live trunk unless you understand exactly what it is doing,” she said, more than once. “And if you have to break that rule, you’d better be damned sure why.”

Her students respected her. Some feared her. All left her classroom with an appreciation for the fact that the difference between a successful repair and a disaster could be as thin as one bit of solder.

They heard stories, of course.

About the phantom engineer in Liverpool who had once risked everything to keep a line alive.

Ellie sat in the back of the mess hall once as a group of new recruits swapped rumors.

“They say he—it—was court-martialed,” one insisted.

“No, no,” another corrected. “He was promoted and shipped to some secret bunker under London. My cousin heard it from a bloke who—”

“They say it was a woman,” a third cut in.

The table fell silent, then erupted into laughter.

“Don’t be daft,” the first one scoffed. “They don’t let women near that kind of stuff.”

At the far end of the table, Ellie picked up her cup of tea, warmed her hands around it, and smiled into the steam.

It was easier that way.

When the war ended, she faded from the Admiralty’s active lists the way a line faded from a status board—slowly, then all at once.

She left the service with a modest pension, a handful of medals for general war service, and a trunk of carefully folded uniforms.

Civilian life felt strangely quiet.

No status boards. No red alarm lights. No convoy charts.

She found work in civilian telecommunications, helping rebuild the damaged networks of a battered country. She taught younger engineers how to lay cable around craters, how to splice lines in basements with no power, how to keep things running when supplies were rationed and everything had to be patched, re-used, re-imagined.

She never married.

Partly because the men she met often thought engineering was a phase she’d grow out of.

Partly because, in the deep of the night, when the house was still, she still heard the hum of the relay racks and felt more married to that memory than to any human.

She kept a notebook on her kitchen table where she scribbled sketches of circuits, ideas for fail-safes, ways to build redundancy into fragile systems.

She wrote into that notebook the way other women wrote diaries.

On one page, in ink faded now to brown, she had written, almost as if reminding herself:

“Every signal is a heartbeat. Keep it alive.”

She died quietly in the late 1970s in a small flat in Portsmouth, her passing noted by a few former colleagues who remembered “that bright Wren who could fix anything.”

Her medals and uniforms went into a trunk in an attic, along with the notebooks, where dust settled on them.

The war rolled farther into the rearview mirror of history.

New wars came. New technologies. Computers, satellites, fiber optics.

The convoys of ships across the Atlantic were replaced by streams of data under it.

And one day in 1989, a naval historian opened a file in the archives and saw a familiar word that didn’t quite connect:

Ghost.

His name was Martin Cook. He was the sort of man who enjoyed footnotes more than headlines.

He’d set out to write a monograph on Royal Navy communications doctrine during the Second World War—something only other historians and a handful of signal officers would ever read. It had led him into basement rooms lined with boxes. Boxes had led to files. Files had led to memos.

And one memo, buried under a stack of more urgent wartime directives, had snagged his attention.

“UNSANCTIONED BUT ESSENTIAL ACTION BY ENGINEER RATINGS, LIVERPOOL STATION,” the heading read.

He read on.

The memo detailed a trunk line failure in December 1942. The timelines. The potential risk to convoy HX-219. The manual intervention by an unnamed engineer.

“By means of a hazardous but technically sound bypass of a degraded relay coil,” the memo said, in the dry language of bureaucrats, “communications were restored within eight minutes, thus averting probable severe losses to shipping.”

There was a scrawl in the margin. Faded pencil, more personal.

“Talk to E. Hart about this.”

Cook sat back.

E. Hart.

He rifled through adjacent folders, fingers nimble despite the dust. Service records. Station lists. Training rosters.

He found her in a personnel file: “Hart, Eleanor. WRNS. Engineering rating, communications branch.”

Her postings matched the memo’s date. Liverpool in late 1942. Transfers thereafter.

There were no commendations in her file beyond the generic. No formal recognition that she had done anything unusual.

He traced her through postwar employment records. England still appreciated good engineers; she’d found work in civilian telecoms.

He found notice of her death. He found a listing for next of kin—a niece in Guildford.

Two weeks later, he sat in that niece’s front room, a cup of tea on a crocheted coaster in front of him, and watched as she hauled a dusty trunk down from the attic.

“We wondered what to do with all this,” she said, more bemused than anything. “Aunt Ellie never spoke much about the war. Just said she did wiring for the Navy.”

Cook opened the trunk as if it might contain unexploded ordnance.

Neatly folded uniforms. A WRNS cap, its badge tarnished. A handful of medals, mostly for general service. A stack of notebooks.

He opened one.

Circuits. Diagrams. Notes in a precise, looping hand.

He flipped past pages of calculations and paused at one with a small, almost casual line scribbled along the bottom margin:

“Every signal is a heartbeat. Keep it alive.”

He felt a shiver run down his spine.

He turned another page and found a rough sketch of a relay rack. A bypass line penciled in around a coil.

The date in the margin: December ’42.

He took a breath.

“This is it,” he murmured.

“What?” the niece asked.

He closed the notebook gently.

“The night your Aunt Ellie saved five hundred ships,” he said.

She stared at him.

“Aunt Ellie?” she repeated, as if trying to reconcile the quiet old woman who’d fixed her toaster and refused to drive a car with the idea of someone performing miracles in a storm.

He wrote the article over the next three months, the way you write something when you know only a handful of people will ever read it but you also know it has to be written.

“The Woman Who Saved the Atlantic Line,” he titled it.

He published it in a modest naval journal. It did not make front pages. It did, however, find its way into the hands of the right people in the Royal Navy.

People who understood that while the world liked to remember admirals and decisive battles, it owed just as much to the anonymous hands that had kept the lines alive.

In 1992, on the fiftieth anniversary of her unsanctioned repair, they decided to say her name out loud.

The old Liverpool base had changed.

The docks around it had modernized, containers stacked where crates and oil drums once stood. The relay room had long ago been stripped of its wartime equipment. Computers now sat where relay racks once hummed.

But the brick building was still there.

On a gray December morning, under a sky that could have belonged to 1942, an honor guard stood at attention outside the entrance. Officers in modern uniforms mingled with veterans in old caps and coats. A few walked with sticks. Some rolled up in wheelchairs.

Inside, a brass plaque lay under a Union Jack.

The First Sea Lord made a short speech.

“We are here,” he said, “to honor a woman who, with one act of courage and ingenuity, saved countless lives—not with guns or ships, but with a soldering iron and a refusal to accept silence.”

He gestured to a framed photograph—Ellie in uniform, hair tucked neatly under her cap, eyes steady.

“Eleanor Hart,” he said, “did what she thought was necessary. For operational security, her name was kept secret. Today, we correct that.”

They pulled away the flag.

“In memory of engineer Eleanor ‘Ellie’ Hart,” the plaque read. “Whose courage and skill restored the Atlantic line on 12 December 1942, saving lives unseen.”

In the crowd, an elderly man with watery blue eyes and a convoy badge on his lapel pressed a hand to his mouth.

“I remember that night,” he whispered to the man next to him. “We were halfway to Iceland. Thought the world had forgotten us. Then the radio flickered back and told us to turn thirty degrees north. We missed a wolf pack by hours, they said later. We never knew who’d done it.”

Now he did.

Tears carved clean paths down cheeks creased by years of salt and wind.

Young signal officers in crisp uniforms stood a little straighter as the story was told. Some had heard the ghost tale in training. Now they had a name.

At the Royal Navy’s communications school, Ellie’s photo went up on the wall, next to a simple engraving of her words:

“Every signal is a heartbeat. Keep it alive.”

In lectures on redundancy and fail-safe design, instructors pointed to her improvised bypass as an early example of crisis innovation—the kind of thinking that modern software engineers might use when they added one critical line of code to reroute traffic around a failing node.

Because that was what she had done, in essence.

In a network made of copper and coils instead of fiber and routers, she had written a new instruction—go here, not there—with flame and metal instead of keystrokes.

One line of code, executed under pressure, that changed the outcome of a battle.

Engineers—men and women both—took inspiration from her. Especially the women, who saw in her a proof that their place in the story did not have to be footnotes.

Her notebooks and tools went into a glass case in a small museum, displayed not as relics of quaint old technology but as artifacts of a mindset: that precision, care, and bravery in the quiet rooms behind the front lines were as heroic as any charge.

Outside of the Navy, the world moved on, as it always does.

But every year, on the anniversary of her repair, the communications control room to the Atlantic fleet held a minute of silence.

Ships at sea were notified in advance.

At oh-oh thirty-two Zulu, the time her bypass had come live, transmissions paused. Consoles went quiet. Radar screens kept sweeping. Men and women stood at their posts and listened to the vast, living silence of the modern ocean—the hiss of waves against hulls, the tick of cooling metal.

Then, at the end of sixty seconds, links came back up. Messages flowed again. Routine status reports. Weather advisories. Emergency calls from fishing boats. Position updates from nuclear submarines.

In a destroyer’s ops room, a young petty officer might lean over her console and whisper, just loud enough for herself to hear:

“Cheers, Ellie.”

Technology had evolved in ways Ellie Hart could never have imagined. Satellites tied continents together. Fiber optic cables carried terabits of data every second under the same ocean where she’d once fought to keep a single line alive.

But at the core of all that, the principle remained the same:

Connections saved lives.

Lose them, and the mightiest fleet in the world blundered in the dark. Keep them, and you had a fighting chance.

History remembers admirals and battleships. It remembers Churchill’s speeches and Roosevelt’s signatures. It remembers U-boat aces and the tonnage they sent to the bottom.

It rarely remembers the woman sitting on a cold floor in a relay room, soldering iron in hand, fingers inches from enough current to stop her heart, who says, “Approval can wait,” and adds the one line of code that keeps five hundred ships on the map.

But sometimes, when the right file gets opened and the right story gets told, that changes.

Eleanor Hart never saw the plaque.

She never heard the minute of silence.

She never watched young engineers, male and female, run their fingers over the engraved words “Every signal is a heartbeat. Keep it alive,” and feel something settle in their chests.

She didn’t need to.

The night she walked home in the rain, exhausted, hoping only that the radios would keep humming till morning—that was enough for her.

The rest is for the rest of us.

THE END

News

CH2 – Paralyzed German Women POWs Were Shocked By the British Soldiers’ Treatment…

On a desolate stretch of road in northern Germany, in the wet, uncertain spring of 1945, a convoy of British…

CH2 – How One Mechanic’s ‘CRAZY’ Trick Let Him Fight 50 Japanese Zeros ALONE — And Saved 1,000 Allies…

At 8:43 on the morning of August 15th, 1943, First Lieutenant Kenneth Walsh watched his wingman scatter across the…

CH2 – How One Crewman’s “Mad” Rigging Let One B-17 Fly Home With Half Its Tail Blown Off

At 20,000 feet above the Tunisian desert, the tail of All-American started to walk away. Tail gunner Sam Sarpalus felt…

CH2 – German Sniper’s Dog Refused to Leave His Injured Master — Americans Saved Him…

The German Shepherd would not stop pulling at the American sergeant’s sleeve. It had started subtle: a tug at the…

CH2 – The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men

The German officer’s boots were too clean for this part of France. He picked his way up the muddy slope…

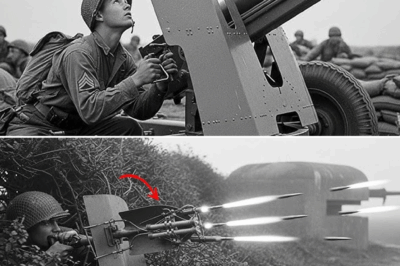

CH2 – This 19-Year-Old Was Manning His First AA Gun — And Accidentally Saved Two Battalions

The night wrapped itself around Bastogne like a fist. It was January 17th, 1945, 0320 hours, and the world, as…

End of content

No more pages to load