The first time Captain Sam Keene heard the phrase “exploding dolls”, he thought somebody in Corps had finally cracked from sleep deprivation.

It was June 1944, and Normandy felt like a fistfight in a phone booth—mud, smoke, wounded men stacked in aid stations that ran out of morphine before they ran out of blood. Keene was U.S. Army G-2, intelligence, attached to a division trying to grind inland from the beaches. He hadn’t slept more than two hours at a stretch since the landings. His world had shrunk into maps, radio traffic, and the constant arithmetic of casualties.

So when a liaison officer—breathless, grinning like a man who’d just seen a ghost—leaned into Keene’s tent and said, “You gotta hear what the Brits pulled the night we hit Omaha,” Keene almost threw him out.

“Not now,” Keene said, eyes on his situation map. “Unless your dolls can kill an MG-42.”

The liaison stared at him a beat, then lowered his voice. “They did,” he said. “Not with bullets. With… noise. Parachutes. Dummy drops. A whole German regiment went chasing shadows while we were getting chewed up on the sand.”

Keene looked up slowly.

Outside, artillery rolled like distant thunder. Somewhere beyond the hedgerows, German guns still owned the high ground. Somewhere behind Keene, the beachhead still swallowed men. Omaha was burning in the memories of everyone who’d been there, even if the actual fires were long out.

Keene had spent his adult life learning one truth the Army did not put on recruiting posters:

Wars are not won only by strength.

They’re won by time.

And time, in Normandy, was the difference between holding the beaches and getting thrown back into the sea.

“Start over,” Keene said. “Slow. What happened?”

The liaison took a breath, and the story that came out sounded like a tall tale until it didn’t. Until it became numbers. Timings. Patrol cycles. The kind of details that only exist when something actually happened.

Six men.

Two hundred burlap “paratroopers.”

Two gramophones playing boot-steps and shouted orders.

And for the first crucial hours of D-Day—while Americans bled on Omaha and fought to open roads from Utah—thousands of German troops hunted ghosts thirty kilometers away.

Keene stared at the liaison as if he were looking at a weapon he’d never seen before.

“Who led it?” Keene asked.

“Lieutenant Frederick Fowls,” the liaison said. “SAS.”

Keene had heard of the SAS. Everybody had. They were the guys who treated enemy territory like a personal challenge. The guys who slipped behind lines, cut wires, blew bridges, then disappeared.

But dolls?

Keene leaned back on his camp stool and listened.

And as the liaison talked, Keene began to understand something he’d never fully grasped in training back in Georgia:

The battlefield isn’t just where men stand and shoot.

It’s where men believe an enemy might be.

RAF Fairford, England

4 June 1944 — 2115 hours

The briefing room smelled like damp wool and cigarette smoke and the kind of stale anxiety that gets baked into wooden walls when too many men have stood inside them waiting to be told what to do next.

Lieutenant Frederick James Fowls sat with his squadron, twenty-eight years old, SAS, listening to an operational order that sounded like either genius or a prank.

Operation Titanic 4.

Jump with 200 “Roberts” near Lemenil-Viggo, 28 kilometers southwest of Utah Beach.

Mission: simulate an 82nd Airborne deployment in the wrong location.

Estimated duration: nine days until American forces overran the position.

Nine days.

Fowls didn’t flinch when the number was read aloud, but the number settled in his mind anyway, heavy as a pack.

Because nine days wasn’t a plan.

Nine days was a wish.

They were six men in the stick—Fowls plus five—carrying:

Sten Mk II 9mm

Webley .38 revolvers

Mills grenades

TR 1936 radio

And non-combat equipment that could get them killed just by being heavy.

Total stick weight: 680 kilograms.

Six men plus equipment plus a radio, plus what looked like an insane cargo manifest:

Two hundred cloth dolls.

Fowls inspected a “Robert” in his hand.

Height: 90 centimeters—three feet.

Material: Hessian sackcloth, filled with 4.5 kilograms of sand and straw.

Parachute: basic 3.6-meter canopy.

Attached devices:

Pintail rifle-fire simulator: 90 seconds of burst fire on ground contact

Window packet: aluminum chaff for radar echo

Explosive charge: 110 grams, 120-second delay, self-destruction

A RAF sergeant watched him weigh it.

“Looks like a scarecrow my grandmother made,” the sergeant said.

Fowls didn’t smile. He didn’t take offense either. His face had the calm, closed expression of a man who treated fear like weather: not something you argued with, just something you worked around.

He looked at the doll again.

A German soldier weighed seventy kilos.

An American paratrooper with full kit weighed one twenty-five.

The Panzergrenadier division defending this sector fielded fourteen thousand real men.

Fowls would drop with two hundred cloth ones.

Beside the dolls sat the audio equipment, crated like something stolen from a church social.

Two modified HMV gramophone players, portable, 8.2 kilograms each, with battery packs.

Playback duration: 45 minutes continuous.

The discs were pre-recorded:

Boots on gravel.

Two hundred men shouting orders in English.

“Move out!”

“Secure that flank!”

M1 Garand fire in controlled bursts.

Vehicle movement.

Engines grinding.

SAS doctrine for Titanic was blunt and practical.

Fowls would split the stick after landing:

Team A: Jenkins + two men — gramophone north

Team B: Fowls + two men — gramophone south

Separation distance: 400 meters to create illusion of a broad front.

Operational time: 15–20 minutes after Robert deployment, then exfiltrate east toward expected American advance.

The problem was weight.

Those gramophones and the radio meant each team carried 22.7 kilograms of dead weight—equipment that didn’t shoot back when Germans found you.

SAS doctrine recommended a maximum of thirty-five kilos per man on infiltration.

Fowls did the math and felt the quiet panic beneath it.

If Americans did not arrive in nine days, every extra kilogram would be carried for every extra day.

A flight lieutenant from 149 Squadron stood by the Sterling and stared at the cargo.

“You’re jumping with dolls,” he said, disbelief creeping into his voice.

Fowls explained the logic without emotion.

“Germans see parachutes. They fire signal flares. Entire regiments mobilize.”

The pilot frowned. “What if they realize they’re dummies?”

“The Pintail simulators fire for ninety seconds,” Fowls said. “The charges explode afterward. What remains is burnt sand and jute.”

The pilot persisted, as pilots do when they’re about to put men into the dark.

“And you six stay on the ground making army noises.”

Fowls nodded.

“For nine days,” the pilot said, as if saying it would make it ridiculous enough not to be true.

Fowls nodded again.

The pilot did not ask the obvious question.

What if the Americans don’t pass through in nine days?

Fowls had read intelligence summaries on the 352nd Infantry Division—concrete bunkers, 88mm guns, intact regiments. Utah Beach was 28 kilometers away. Omaha 35.

Nine days was optimism.

But optimism was what the plan required.

Fowls slung his Sten and boarded the Sterling.

Normandy, France

5 June 1944 — 2352 hours

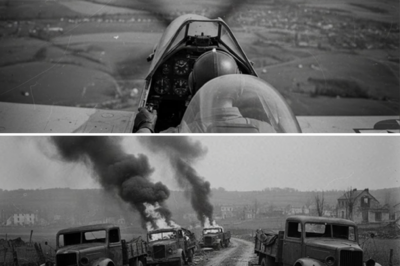

Altitude: 180 meters—600 feet.

Standard cargo drop height.

Air speed: 185 kilometers per hour.

Sky: full moon after rain, visibility good.

Norman bocage fields below looked like silver patchwork under moonlight—hedgerows like veins, lanes like scars.

At 2352, RAF crew began pushing Roberts through the side door at roughly 15 dummies per minute.

The last Robert went out at 0005 on the 6th of June.

Fowls and his stick jumped at 0007.

Freefall time: 22 seconds.

Landing: bocage field, tall grass one to one-and-a-half meters high.

Fowls hit hard, rolled, released his parachute, brought up the Sten, swept 360 degrees.

Darkness.

Grass moving in wind.

Fabric tearing.

Parachutes landing.

Jenkins appeared fifteen meters away, gave a hand signal: four fingers.

Four men accounted for.

Fowls waited.

The fifth man did not appear.

Stick of six reduced to five at the initial rally point.

Standard attrition for night jumps at low altitude—broken ankle, off-target landing, both common.

At 0011, the first Pintail detonation fired north—rat-tat bursts simulating M1 Garand fire.

At 0012, another fired west.

Between 0012 and 0015, Pintails cascaded across roughly a square kilometer. From a distance it sounded like a dispersed platoon opening fire.

Fowls timed it.

Ninety seconds of simulated gunfire.

After that, the charges would detonate.

He had ninety seconds to position gramophones before silence returned.

At 0013, Fowls split the stick.

Team A: Jenkins, Corporal Hewitt, Private Morrison—400 meters north. Gramophone behind a stone fence. Disc loaded: marching column + vehicle movement.

Team B: Fowls, Sergeant Davies, one private—350 meters south. Gramophone in a terrain depression. Disc loaded: orders + rifle fire.

At 0016, Fowls cranked the gramophone handle.

The turntable spun.

Boots on gravel.

Two hundred men marching.

Volume max.

On a calm night, sound carried 800 meters.

Fowls stared east toward the village lights—Lemenil-Viggo, 2.3 kilometers away.

Some German was listening.

Some German was reaching for a field telephone.

Some German was waking a company commander.

At 0018, first self-destruct charge: whump—orange flash at 300 meters. A Robert destroyed, leaving burning sand and jute.

Between 0018 and 0022, explosions cascaded—two hundred small detonations across the drop zone, intermittent flashes lighting the field like summer lightning.

At 0031, German reaction:

First signal flare—green—from Lemenil-Viggo.

Forty-second pause.

Three red flares.

Maximum alert.

Two white flares—illumination.

Fowls glassed the village through binoculars. Vehicle lights ignited, headlights covered, diesel engines stirring. Opel Blitz trucks. Reconnaissance platoon deploying.

At 0047, gramophones shut down.

Actual playback time: 31 minutes—fourteen minutes short of design spec, battery degradation or defect.

Fowls ordered equipment recovery.

They couldn’t risk capture.

They buried gramophones—eight minutes.

At 0103, Germans reached the drop zone.

Voices. Engines stopping.

Fowls estimated 40–60 soldiers searching the field. Flashlights bobbing. They’d find burnt sand, charred jute, fragments of Pintail simulators, two hundred craters where Roberts landed.

It would take twenty minutes for an officer to understand.

Dummies.

Another ten to report.

Another thirty to decide whether deception was total or partial.

Fowls needed sixty minutes of confusion.

He had 31 minutes of audio plus an estimated 40 minutes of German investigation.

Total: 71 minutes.

Enough.

At 0115, exfiltration began.

Five men.

Twenty-eight kilometers to Utah Beach.

Nine days until Americans arrived.

They started moving east.

6–8 June 1944

The first three days were the plan and the lie fighting each other.

SAS protocol: move only in darkness—1830 to 0500.

Distance per night: three to five kilometers through bocage so tight it felt like moving through a hedgerow maze built to trap men.

Daytime rest: improvised shelters, radio silence, rations—emergency biscuits, concentrated tea, chocolate.

On 8 June, 1400, Fowls heard heavy artillery to the west.

Utah was east.

The artillery was behind them.

Meaning Americans hadn’t advanced 28 kilometers in three days.

Probably still contained at the beachheads.

Fowls recalculated in his head like a man adjusting a sight picture.

If Americans advanced at two kilometers per day—slow in bocage—then Americans would overrun them in 14 days, not nine.

Fowls carried rations for ten.

On 9 June, 0730, the stick held a conference.

Option A: immediate exfiltration, move east, attempt to reach American lines—cross twenty-plus kilometers of German territory. Success probability: 40% by doctrinal assessment.

Option B: wait as planned. Risk: rations exhausted in five days, no certainty Americans would arrive.

Option C: active operations—remain, conduct sabotage, gather intelligence. Risk exposure increases capture probability. Benefit: keep Germans hunting here instead of sending troops to the beaches.

Fowls spoke quietly:

“We jumped to make the Germans think an army was here. We succeeded. But if we just wait, they’ll realize it was deception and reposition divisions to the beaches. If we keep acting—sabotage, intelligence—they’ll have to keep troops here to hunt us. Operation Titanic doesn’t end when the Roberts exploded. It ends when the Americans arrive or when we’re killed.”

Vote: unanimous.

Active operations.

10 June–22 June 1944

The Ghost War

On 10 June, 2345, they hit a German field telephone line—1.8 kilometers from Lemenil-Viggo—connecting a command bunker to an artillery position.

Guards: two sentries, patrol cycle ninety minutes.

Jenkins and Davies took security north and south.

Fowls and Hewitt cut three copper wires.

No fire, no drama—just silence that would bloom into confusion at dawn.

The Germans would have dead telephone in the morning. Six to eight hours to locate the break. Two to three to repair.

A day of disrupted communications.

Small impact.

But repeated, it became cumulative.

Then came the rhythm of it:

Sabotage: electrical transformer, 200g plastic explosive

Sabotage: telephone cable cut

Intelligence: convoy observed—12 Opel Blitz trucks moving west

Sabotage: fuel depot—five 200-liter drums, incendiary

Intelligence: unit ID—352nd Infantry Division confirmed

Sabotage: wooden bridge demolished

Intelligence: Panzer column observed—eight vehicles, likely 21st Panzer

Sabotage: secondary rail line cut with demolition charge

Then the cost.

Rations exhausted 19 June.

Foraging began. Eggs from isolated farms. Potatoes and vegetables taken at night. Water from streams purified with halazone tablets.

Risk increased every time they approached civilian life.

And every sabotage tightened the net.

German patrols increased from two per day on 10 June to five per day by 22 June.

The Germans were hunting.

Not paratroopers.

Not an invasion force.

Five men with a Sten and a radio.

But hunting all the same.

6 July 1944 — 0815 hours

The Radio Dies

The TR 1936 was their only link to Allied command.

During night movement, Davies tripped on a wire fence and fell—1.2 meters—with the 14.5 kg radio on his back.

Impact shattered thermionic valve number three.

Transmission impossible.

Fowls disassembled the radio, tried repair. The 3AT valve was irreplaceable.

He improvised—reconnected circuitry, bypassed the broken valve.

Outcome: receiver functional.

Transmitter dead.

They could listen.

They could not speak.

Fowls tuned to BBC.

News: American troops captured Carentan.

Carentan was eighteen kilometers northeast.

Americans were advancing—but north toward Cherbourg, not west toward Lemenil-Viggo and St. Lô.

Conclusion: they were isolated.

Americans might not reach them for days.

Possibly weeks.

Decision: continue operations until breakout to Allied lines became possible.

8–12 July 1944

The Hunt Tightens

German patrols intensified. Posters appeared on telegraph poles—German and French—rewards for information on saboteurs.

Dogs observed twice.

FA223 Dra observation helicopter spotted once, 10 July.

Countermeasures: daytime movement suspended, shelters changed every 24 hours, never sleep in same location, increased security distance from sabotage sites, reduced foraging.

On 13 July, 2340, first enemy contact.

Night movement near woodland three kilometers from St. Lô.

German patrol, six soldiers, at eighty meters.

Fowls ordered total immobility.

Patrol passed without detection.

Post-contact analysis: six German soldiers dedicated to hunting five commandos.

One-to-one ratio.

Inefficient.

But if there were six patrols—a battalion standard—that meant thirty-six soldiers hunting five men.

And if an entire battalion was dedicated to the hunt, then maybe the later citation’s line would be true:

That something like a division’s worth of attention—if not a full division—had been pulled to chase ghosts.

15 July 1944 — 0600 hours

The Breakout Decision

Forty days since jump.

Planned duration: nine days.

Rations: zero for twenty-six days.

Ammunition: Sten 94 rounds 9mm, Webley 47 rounds .45 ACP, Mills grenades three.

Health: weight loss eight to twelve kilograms. Davies showing dysentery symptoms. Fever. Weakness.

Radio still broken.

Twenty-three intelligence reports documented on paper.

Not transmitted.

Fowls said, “We’ve completed the mission. Germans kept troops here hunting us while Americans took Carentan and advanced north. But we can’t keep sabotaging without ammunition, and Davies needs treatment. We go east.”

Three nights of movement.

Objective: reach American positions near Lâmes sector (as they understood from broadcasts).

Night one: 15–16 July, 6.2 kilometers east. Two German patrols spotted. Avoided.

Night two: 16–17 July, 5.8 kilometers. Artillery sounds increased—combat zone closer. Davies worse.

Night three: 17 July, 0300, 3 kilometers only due to Davies.

At 0415, Fowls identified American positions roughly 2 kilometers distant—red tracers from .30 caliber weapons.

Decision: wait for dawn before crossing final gap to avoid friendly fire.

At 0430, holding position.

Fowls chose a drainage ditch 180 meters from the last fence before no man’s land.

Ditch depth 1.2 meters—cover.

Plan: at dawn around 0600, advance hands raised, identify in English.

Davies lay shaking.

Jenkins checked broken radio one final time.

Nothing.

Hewitt counted ammunition.

Forty-seven rounds .45 ACP.

Three Mills grenades.

And six weeks of intelligence.

At 0437 hours, Fowls heard boots.

German.

The patrol was close—forty meters.

You could hear the bolt of a Kar98k being drawn.

The German patrol stopped.

Fowls risked looking above the ditch rim.

A German soldier bent down and lifted something from the ground.

Olive-green parachute fabric—British issue.

The fabric Jenkins had used three days earlier to wrap a twisted ankle and discarded yesterday.

The soldier showed it to a sergeant.

The sergeant turned toward the ditch.

Fowls tightened his grip on the Sten.

Impossible decision.

Option A: open fire first. Surprise, but eight Germans versus five exhausted men. Noise would bring more patrols. No chance to reach American lines.

Option B: surrender. Possible survival as POW—but twenty-three intelligence reports captured.

Option C: wait and hope Germans pass. Unlikely.

Fowls prepared for A, but waited until the last second.

At 0440, Germans advanced, splitting patrol—four flanking south, four north—standard clearing method.

Distance: twenty meters.

Fowls whispered: “On my signal.”

Three grenades.

Then something happened that none of them could have planned.

At 0441, an explosion erupted behind the German patrol.

An American 81mm mortar round.

Then another.

Then four more.

A walking barrage.

The Germans threw themselves down. One panicked and ran—toward the ditch.

Fifteen meters.

Ten.

Fowls raised the Sten.

Did not fire.

The German soldier jumped into the ditch seeking cover.

He landed two meters from Jenkins.

In the chaos of shells, the soldier turned his head and saw five men in British uniforms.

His eyes widened.

At 0442, Jenkins struck him with the Sten buttstock. The soldier went limp.

Fowls heard shouts in German above them.

Mortars still falling.

He climbed to the ditch rim and saw five German soldiers running west, fleeing the barrage. Two lay wounded in the open.

One turned, raised his Kar98k.

Fowls fired the Sten—three rounds.

The German fell.

Then a new problem:

The Americans—180 meters away—didn’t know who Fowls was.

They saw muzzle flashes.

They saw Germans.

They fired.

.30 caliber tracers ripped past a meter above the ditch.

Fowls shouted, “Friends! British SAS! Don’t shoot!”

Impossible to be heard over mortars.

At 0444, German counterattack.

Vehicle approaching—likely an SdKfz 251 halftrack.

An MG42 opened fire toward the ditch.

Dirt exploded around them as if the earth itself had turned into shrapnel.

Fowls made a decision.

“Grenades. Now.”

Three Mills grenades.

Hewitt threw first—four-second fuse.

Second.

Third.

The halftrack stopped.

MG42 silenced.

At 0446, the situation deteriorated further.

Sten ammunition nearly gone—about twenty rounds remaining.

Germans reorganizing at sixty meters.

Americans still firing, still unaware the men in the ditch were allied.

At 0447, German infantry advanced—twelve to fifteen soldiers in a skirmish line, forty meters from the ditch.

Fowls fired the last Sten rounds.

Two Germans fell.

Then the Sten jammed—magazine empty.

German soldiers readied stick grenades.

They threw.

Fowls shouted down.

Five men flattened at the bottom of a 1.2-meter ditch.

Crump. Crump. Crump.

Explosions above, shrapnel hissing overhead.

Then the fourth grenade fell inside the ditch.

Three meters from Fowls.

Four seconds to detonation.

He couldn’t reach it to throw it out.

Jenkins tried.

Couldn’t reach.

At 0448, the grenade detonated inside the ditch.

All five men were wounded.

Fowls took shrapnel in left arm and thigh.

Jenkins caught fragments in his back.

Davies—already feverish—was unconscious and now had fragments in his legs.

Hewitt had a facial wound.

The fifth man took a severe abdominal wound.

At 0450, German soldiers appeared at the ditch rim, rifles pointed down.

Fowls raised his right hand.

Blood ran from his left arm.

A German sergeant shouted something—“Hand!”

Fowls understood enough.

Hands up.

The forty-two-day war of Frederick Fowls ended 180 meters from American lines.

17 July 1944 – April 1945

Prisoner

Fowls was treated at a German field hospital. Then transferred to a stalag.

Davies died of infection eight days after capture—likely dysentery plus wounds.

Documentation later mentioned SAS killed in Titanic but did not specify all names.

Fowls survived.

April 1945, Allied forces liberated prison camps.

Fowls repatriated to England.

Weight at capture: ~65 kg.

Weight at liberation: ~52 kg.

MI9 debriefing.

Escape and evasion intelligence.

The twenty-three handwritten intelligence reports on the 352nd were recovered—Germans had not destroyed them.

They later appeared as evidence in war crimes trials.

Spring 1945, at an awards ceremony, a general presented the Military Cross.

Citation praised extraordinary initiative and devotion to duty while operating behind enemy lines in Normandy for six weeks. Despite mistiming and failure of American forces to reach his position as planned, Fowls conducted sustained sabotage and intelligence gathering that drew away approximately one enemy division from the American area, contributing to the success of the landings.

The general did not mention the Roberts.

Did not mention the HMV gramophones.

Did not mention that six men, armed with cloth dolls, had held thousands of Germans chasing ghosts while Omaha burned and Utah fought to expand.

Postwar analysis—based on documentation—estimated that across Titanic sub-operations, the 352nd kept a regiment searching for paratroopers during the critical first three days. Elements of the 21st Panzer diverted to investigate drops elsewhere. Reserve troops retained in defensive positions instead of counterattacking beaches.

Conservative estimate: five to eight thousand German soldiers diverted in the first 72 hours.

Time gained: 24 to 48 hours without massive counterattacks on Utah and Omaha.

Cost: 11 SAS killed, executed, or missing.

Budget: £12,000 in 1944 currency.

And yet the operation never became a household story.

No Hollywood film.

No giant monument.

Just a burlap doll in a museum.

Years Later — An American Memory

Captain Sam Keene heard the story in a tent in Normandy and carried it like a new kind of weapon in his mind.

Not because dolls were funny.

Because the logic behind them was brutal and pure:

On D-Day, the enemy didn’t need certainty to react.

The enemy needed possibility.

A parachute in the dark was possibility.

Gunfire in a field was possibility.

Boots on gravel in the night—recorded, amplified, lying—was possibility.

For ninety seconds, a Hessian scarecrow fell from the sky and became indistinguishable from a living man.

For thirty-one minutes, gramophones made an army appear where none existed.

For seventy-one minutes, German officers argued whether the threat was real.

For three days, units stayed searching, probing, holding back reserves, because what if the drop wasn’t a trick?

And while that question lived in their heads, American soldiers climbed off landing craft, crossed fire lanes, and fought to make the beaches permanent.

Keene later wrote a line in his own notebook—a private note he never put in any official report, because nobody asked for poetry from intelligence officers.

“Wars are won by bullets, but invasions are won by hesitation.”

Frederick Fowls and his men manufactured hesitation with exploding dolls.

And that hesitation bought Americans time.

Time to build dumps.

Time to bring tanks ashore.

Time to push out of the surf and into France.

Time—measured not in speeches, but in hours.

The story stayed quiet.

Like the men who did it.

But it happened.

And on the most important night of the war, while Omaha burned, eight thousand Germans hunted ghosts.

THE END

News

CH2 – The Ghost Shell That Turned Tiger Armor Into Paper — German Commanders Were Left Stunned Silence

The hole was the size of a thumb. That was what got you, standing there in the Maryland winter with…

CH2 – Japanese Metallurgists Examined American Bullet Casings — Then Learned Why Their Own Weapons Jammed

The rain over Tokyo had a way of making the city feel like it was holding its breath. October 27th,…

CH2 – How One Woman Exposed a 6-Submarine Japanese Trap That Could Have Killed 10,000 Americans

At 2:17 a.m. on February 12th, 1944, Station HYPO didn’t feel like the nerve center of the Pacific War. It…

The Forgotten Plane That Hunted German Subs Into Extinction — The Wolves Became Sheep

May 1943. Gray dawn broke over the North Atlantic like a bruise spreading across steel. A lone merchant ship limped…

CH2 – They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass

May 1944. A P-51 Mustang screamed down toward a German convoy at seven hundred feet per second, nose pitched sixty…

His Crew Thought He Was Out of His Mind — Until His Maneuver Stopped 14 Attackers Cold

The first thing you learned in the Eighth Air Force was that daylight had teeth. Not the kind of teeth…

End of content

No more pages to load