The German officer’s boots were too clean for this part of France.

He picked his way up the muddy slope like a man trying not to scuff his own dignity, white flag in one hand, the other smoothing invisible wrinkles from his field-gray tunic. Behind him, on the far side of the ruined bridge, seven hundred German soldiers waited among trees and rubble and camouflaged guns.

On the hill above, thirty-five American paratroopers watched him come.

Sergeant Jake McNiss leaned on his rifle and squinted down the slope. He was twenty-five years old, face streaked with dried mud and war paint, hair hacked into something halfway between a Mohawk and a bad barber joke, uniform torn, boots caked in three days’ worth of blood and grass stains. He hadn’t shaved in a week. He hadn’t eaten anything but grass and rainwater in three days.

And the United States Army had tried to throw him out eight separate times.

The officer stopped halfway up, as if he’d just realized how much uphill was left, then pushed on to the little flat spot just below the American line. He planted the white flag in the ground like he expected applause.

“Sergeant!” he called in careful English. “I am asking you to surrender.”

Jake stepped out from behind a splintered tree trunk and walked down until he stood ten yards from the officer, just far enough that neither of them could pretend this was a friendly visit.

The German took him in—war paint, Mohawk, the filthy state of him—and his mouth twitched, like he’d expected scared kids, not this half-starved scarecrow with crazy eyes.

“You are McNiss?” he asked.

“That’s me,” Jake said. “You’re early. We figured you’d try dying this afternoon.”

The German blinked. “You are surrounded. You have no food, no water, no reinforcements. This position is untenable.” He spoke like a man reading off a menu. “You have, by my count, thirty to forty men. I have more than seven hundred. If you surrender now, I give you my word your men will be treated according to—”

“Hold up,” Jake said mildly. “How many?”

The officer frowned. “Seven hundred.”

Jake whistled low. “Boys,” he called over his shoulder, “hear that? There’s seven hundred of ‘em. I owe somebody ten bucks.”

A few tired chuckles floated down from the American foxholes.

The German officer composed himself. “Sergeant, you must understand. No help is coming. You are cut off from your army. Your bridge is destroyed. You have no mission. There is no escape. Surrender is the only logical choice.”

At the mention of the bridge, something like a grin tugged at the corner of Jake’s mouth.

The bridge. Yeah. That figured.

He looked past the German, down at the twisted wreck of stone and steel they’d spent all of June 6th bleeding for while every German gun in Normandy tried to turn them into fertilizer.

He watched the river crawl around the wreckage and thought briefly of the planes—his own planes—rolling in low and fat and friendly, sunlight glinting off American stars on their wings before they’d dropped bombs right on top of the damn thing. Right on top of him.

Logic, huh?

“Let me save you some time, Captain,” he said. “You got three options. One, you turn around, go back down that hill, tell your boys it’s canceled on account of we’re in a bad mood. Two, you sit down here with me, we talk it over, maybe we figure out how you can live long enough to lose this war somewhere else. Three, you walk back down there, tell your men to attack uphill into fortified machine-gun positions held by paratroopers who have been eating grass for three days and are extremely, extremely pissed off.”

The German’s jaw tightened. “You are in no position to make jokes, Sergeant. You have no supplies. We have artillery. We have armor. You cannot win.”

“Didn’t say anything about winning,” Jake said. “I’m saying if you pick door number three, you and a whole lot of your friends are going to die badly before lunch, and I’m fresh out of sympathy.”

The officer studied him for a long moment, looking for something—fear, maybe, or bluff. He found neither.

“What you are doing is not rational,” he said. “This is madness.”

Jake’s eyes went distant for a second, across the river, across the days, back to a burning plane over Normandy and a bridge that didn’t exist anymore because some staff officer had misread a map. Back before the Mohawk, back before the war paint and the grass.

Back before Fort Benning, before the Army had lined him up with a thousand soft-handed boys and tried to cram him into a mold he had never fit.

“Buddy,” Jake said quietly, “logic was back in Georgia. Out here, all we got is the job.”

He turned, walked back up toward his line without looking to see whether the German had saluted or sputtered or pulled a pistol. It didn’t matter. That part was finished. The next part would start when the artillery did.

Behind him, the officer called something in German and trudged back downhill, white flag folded away like a tool he wouldn’t be needing again.

The first time the Army tried to get rid of Jake McNiss, he was standing in a mess line in Fort Benning, Georgia, holding a tin tray that still smelled faintly of bleach.

It was 1942, the Great Depression had bled into a war, and Jake was nineteen, skinny but hard from long Oklahoma farm days, one of ten kids who’d grown up thinking “supper” meant whatever you had managed to trap or shoot that afternoon.

He had a buzz cut instead of a Mohawk, no war paint yet, just a pair of gray eyes that always seemed to be measuring things: distances, angles, the way a man’s tone told you more than his words.

The mess sergeant slid a scoop of eggs onto his tray, then a couple of pancakes that looked about as excited to be there as the men eating them. Another soldier bumped Jake from behind, impatient.

Jake stepped forward. The cook dropped a pat of butter onto his plate, the first thing that had looked like real food all morning.

He moved down the line.

Halfway to the end, a staff sergeant with a bulldog neck and an easy sneer reached out with his fork and dragged the butter off Jake’s tray onto his own.

Jake stopped.

“Sergeant,” he said, calm as a Sunday morning, “you just stole my butter.”

The sergeant didn’t even look up. “Move along, private. You got your issue.”

Jake looked at his tray: limp eggs, rubber pancakes. Then he looked at the butter, slowly melting into the sergeant’s grits.

“I didn’t,” he said.

The sergeant raised his head, eyes mean. “You calling me a thief, boy?”

“I’m calling that my butter,” Jake said. “And I’m telling you, polite as possible, to give it back.”

The mess hall went quiet in the way a building full of men goes quiet when it smells a fight. Forks paused halfway to mouths. Somewhere a chair scraped.

The staff sergeant stood up, coming in close so Jake could smell stale coffee on his breath.

“You think you’re some kind of hotshot?” he growled. “You ain’t nothing but another Okie farm boy in government pajamas. You don’t own a damn thing here. Not your butter, not your rifle, not even your own sorry ass. The Army owns you. Now move. Along.”

Jake looked at him, at the chevrons, at the ring of soldiers watching with that hungry look men get when someone else is about to make their day interesting.

Then he sighed.

“Sergeant,” he said, “I came here to kill Nazis, not to get pushed around over breakfast.”

He set his tray on the nearest table.

The first punch broke the staff sergeant’s nose with a wet crunch. Blood sprayed across the pancakes like syrup. The second punch put him hard on his back, staring up at the ceiling fans while the mess hall exploded.

By the time the MPs arrived, Jake was standing calm beside the unconscious sergeant, hands at his sides, breathing hard but steady.

“You done?” one MP asked.

“For now,” Jake said.

Two hours later he stood at rigid parade rest, knuckles scraped, in front of Captain Harris’s desk. The captain was a lean man in his thirties with the worn patience of someone who’d spent too long dealing with Army paperwork and young idiots.

He flipped through Jake’s thin file, which already had more ink than most.

“You’ve been here one week,” Harris said. “One week, and I already have a formal complaint for assaulting a noncommissioned officer.”

“Yes, sir,” Jake said.

“You broke his nose.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Over… butter.”

Jake’s jaw twitched. “With respect, sir, it wasn’t about the butter.”

“Oh?” Harris leaned back. “Enlighten me.”

Jake stared straight ahead over the captain’s shoulder. “Sir, you asked me yesterday if I understood discipline. I do. Discipline is doing what needs doing when it needs doing, whether you feel like it or not. That sergeant wasn’t enforcing discipline. He was throwing his weight around. That kind of thing gets men killed where it counts.”

Harris rubbed his eyes. “God help me, I think you actually believe this isn’t your fault.”

“It’s my fault I hit him,” Jake said. “That part’s on me. But if you let men like that train your paratroopers, you’re gonna have a lot of dead boys in French fields, sir.”

Silence stretched between them.

“You know,” Harris said finally, “if I were smart, I’d sign these discharge papers and send you back to your fishing hole in Oklahoma.”

“You might be smart, sir,” Jake said. “Or you might be wasting the best demolition man in this battalion.”

Harris raised an eyebrow. “You, huh.”

“Ran your training course this morning,” Jake said. “Beat your record by forty-seven seconds.”

That part, at least, was undeniable. The report was on Harris’s desk: fastest time on the demolition course in Fort Benning history. He’d thought it was a clerical error.

“You unattached farmboy from Ponca City just waltzed in here and beat every trained man I’ve got on explosives,” Harris said.

“Yes, sir.”

“And then broke a staff sergeant’s nose.”

“Yes, sir.”

Harris stared at him another long second, then snorted.

“You’re an insubordinate pain in the ass, McNiss,” he said. “You refuse to stand at attention. You won’t salute unless someone’s won your personal stamp of approval. You called morning colors a ‘dog and pony show’ in front of my first sergeant.”

Jake said nothing.

“But,” Harris went on, “you can run, you can shoot, you can blow things up exactly when and how I tell you to. You’re exactly the kind of lunatic we need to drop out of airplanes behind German lines.”

Jake felt the smallest spark of exhilaration flare in his chest. He kept it off his face.

“So here’s the deal,” Harris said. “I should kick you out. Instead, I’m going to do something that, if my mother were here, she would call damned foolish.”

He shuffled papers, pulled out a single sheet.

“I’m putting you in charge of your own platoon.”

Jake blinked. “Sir?”

“You heard me. We got ourselves a little collection of problem children here in Benning. Men too good at killing to throw out, too bad at following orders to keep with regular troops. You’re going to live with them, train with them, command them. Your own barracks. Your own little kingdom of misfits. Far away from the rest of my formation so you don’t infect anybody.”

Jake opened his mouth, then closed it. Finally he said, “What’s the catch?”

“The catch,” Harris said, “is that if your little circus embarrasses this division again, I will personally see to it that your next assignment is shoveling horse manure at some supply depot in Kansas until this war is over. Do I make myself clear, Private?”

“Yes, sir.” Jake’s mouth almost curved into a grin. “Crystal.”

They called themselves the Filthy Thirteen before the Army did.

The name started as a joke, the way most true things do. There wasn’t actually thirteen of them at first—just Jake and a handful of men the 101st Airborne had stamped “discipline problems” in red ink and quietly shuttled off to the far corner of Fort Benning.

Jack Wimmer came first, a thick-muscled coal miner from Pennsylvania with forearms like tree trunks and a calm, unsettling way of looking at a man like he was measuring whether his nose would break left or right. He’d broken three MPs’ noses over a poker game and still held the best marksmanship scores in the regiment.

Then came Charles Plowo, lean and sharp in that New York way, who spoke four languages and could switch accents mid-sentence. He’d been running a black-market supply racket out of the quartermaster’s office, trading Army socks and rations for cigarettes and whiskey in three different towns before someone with a ledger noticed things didn’t add up.

Robert Conn showed up with a smile on his face and fresh powder burns on his hands after he’d decided to see what would happen if you wired a latrine with enough TNT to “make it interesting.”

Joe Allescuitch from Chicago walked into Jake’s barracks, saw two duffel bags on his bunk, dropped them on the floor, and knocked the owner out with a single punch. He’d gone fourteen for fourteen in boxing matches during basic and never learned the phrase “pick on someone your own size.”

They came one by one, each with an incident or eight trailing behind them like empty shell casings.

Each time, Harris would appear in Jake’s doorway, folder in hand.

“Another gift for you, McNiss,” he’d say. “Too mean to discharge, too crazy for anyone else.”

Jake would square the new arrival with that measuring gaze of his, looking past the swagger and the bruises for one question: Could this man do the job when it counted?

If the answer was yes, he stayed. If it was no, Jake went back to Harris and, with no joy and no drama, asked that the man be reassigned.

“Discipline and obedience,” Jake told them the first night they were all finally under one roof, “are two different animals. The officers up the hill don’t know the difference, so they get offended when you don’t dance to their music. I don’t care if you salute. I don’t care if your boots shine. I don’t care if you call me ‘sergeant’ or ‘hey, you.’”

They were lounging on bunks and footlockers, some smoking, some cleaning rifles, everyone listening without looking like they were listening.

“What I care about,” Jake said, “is that when I say ‘get up that hill,’ you don’t argue about the angle. I care that when it’s dark and loud and bad up there, you can put bullets where they need to go and charges where they’re supposed to blow. I care that you don’t leave your buddy hanging. Be competent or be gone. That’s the only rule.”

“So we ain’t gotta salute nobody?” Joe asked from his bunk.

“You salute whoever you honestly think deserves it,” Jake said. “Just don’t be surprised if they throw you in the stockade for it.”

Wimmer spat tobacco into an old can. “What about showering?”

Jake looked at the lineup of dirt-streaked faces and stained undershirts. “I said competent,” he replied. “Didn’t say pretty.”

Someone snorted. Someone else muttered, “Filthy sons of—”

“Thirteen,” Plowo said from the corner, counting heads. “We’re thirteen if you include Sergeant Butter Thief here.”

The name stuck.

The Army hated them in all the predictable ways.

They hated that the Filthy Thirteen skipped morning parade formations if there was live-fire training to be had, or showed up late with mud on their boots and grins on their faces. They hated that the platoon’s quarters constantly smelled like gun oil, sweat, and contraband bacon instead of disinfectant. They especially hated that every time there was a competition—marksmanship, obstacle course, demolition drills—Jake’s filthy little circus dismantled everyone else’s scores.

Harris, for his part, watched the numbers with a sinking kind of pride.

“Your men are winning every contest I put in front of them,” he told Jake one evening, sliding test results across his desk. “They’ve set new records in route marches, demolitions, hand-to-hand, pistol, rifle, even damn bayonet drill. The only category they’re failing is uniform inspection. I have other officers asking why I don’t make you shape them up. I’d like to know that myself.”

Jake shifted in his chair. “Sir, with respect, if you want men who can stand at attention, there’s plenty down the hill. You want men who can hit French beachheads at midnight and wreck German supply lines on no notice, that’s us. I ain’t wasting time polishing boots while there’s bridges that need blowing.”

“Your insubordination is undermining discipline,” Harris said, but there wasn’t much heat in it.

“Sir, when one of your parade-ground units can outshoot, outmarch, and outfight my boys, I’ll put ‘em in a line and teach ‘em to shine for you,” Jake said.

Harris stared at him for a long moment, then barked a short laugh he tried, and failed, to cover with a cough.

“Get out of my office, McNiss,” he said. “And try not to start any international incidents.”

The second time the Army seriously thought about getting rid of Jake, it was because of two military policemen and a street sign.

It was a Friday night in town off-base, the air thick with cigarette smoke and jukebox music, the bar full of uniforms. The Filthy Thirteen occupied a corner table littered with empty glasses and dented beer cans. For once, they weren’t causing trouble. Trouble came to them.

Two MPs in crisp uniforms pushed through the door, eyes already narrowed. They did a slow, disapproving circuit of the room and settled on Jake’s table like vultures picking a carcass.

“You men from Benning?” one asked.

“Nope,” Joe said. “We’re the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.”

The MP ignored him. His gaze fixed on one of Jake’s men who’d dozed off with his head on his folded arms, a half-finished beer beside him.

“You,” the MP said, jabbing a finger. “On your feet. You’re drunk and disorderly.”

Jake stood up before the private could. “He’s off duty,” he said. “We all are. We’ll take him back to barracks. No harm done.”

“Sit down, soldier,” the MP snapped. “We’ll handle this.”

Jake’s eyes cooled. “That’s one of my men you’re talking about.”

“And I’m ordering you to sit down,” the MP repeated, hand drifting toward his holster. “Unless you’d like to spend the night in lockup with him.”

Jake looked at the man’s hand, then at his face.

“Well,” he said softly, “if you’re gonna pull a gun on me…”

The first MP’s jaw broke as easily as the staff sergeant’s nose had.

The second MP had his pistol halfway out before Joe hit him from the side like a freight train. The Colt 1911 skittered across the floor. Somebody stepped on it. Somebody else kicked it away. The jukebox hiccuped and kept playing.

When the MPs woke up, Jake was sitting at the bar sipping water, both of their pistols lined up neatly beside him.

“Those are government property,” one MP mumbled through split lips.

“Yes, sir,” Jake said. He picked one up, checked the chamber, then headed outside.

On the street, beneath a flickering lamppost, he raised the pistol, sighted on a metal sign that read NO PARKING, and emptied the magazine. The .45’s bark echoed down the block. The sign danced and tore, riddled with perfectly spaced holes.

He reloaded with the second pistol and repeated the exercise on the back of the same sign, just to be sure.

By the time the town cops arrived, they found Jake sitting on the curb, pistols unloaded and laid out beside him, hands resting peacefully on his knees. He stood when they told him to, didn’t resist when they cuffed him and marched him off to their truck.

In the morning, he was back in front of Harris’s desk with a swelling bruise on his cheekbone and that same unreadable expression.

“Eight disciplinary write-ups,” Harris said, flipping the file open. “Assaulting a staff sergeant. Assaulting two MPs. Shooting up a street sign with government sidearms. Refusing to salute. Refusing to stand at attention. Refusing goddamn everything.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I should court-martial you,” Harris said. “You know that? I should toss you in Leavenworth, let you break rocks for the rest of this war.”

“Yes, sir.”

Harris slammed the folder shut. “Instead, I’m going to offer you a bet. There’s a long-standing record at this post for a forced march: one hundred and thirty-six miles to the next base in full combat kit. A handful of men have finished it. Nobody’s ever done it without changing socks and boots. You volunteer your merry band of lunatics to attempt it. You, personally, finish it without so much as a blister, I tear up this paperwork. All of it.”

Jake thought of Leavenworth. He thought of his men. He thought of walking.

“How much time we got?” he asked.

Harris glanced at his watch. “You step off at 0600 tomorrow.”

Jake nodded once. “We’ll be ready.”

Ten days later, he limped back into Fort Benning looking like something the cat wouldn’t have had the heart to drag in.

He dropped his sixty-pound rucksack with a thud, stood at loose attention in front of the cluster of officers and medics waiting for him, and stared straight ahead while a doctor knelt to unlace his boots.

The crowd murmured as the boots came off. Jake wiggled his toes.

Not a blister. Not a raw spot. Just calloused, ugly feet that had been hauling him across fields and backwoods since he was ten years old, now wrapped in sweat-soaked socks that somehow hadn’t chewed him up.

The doctor looked up at Harris, eyes wide. “I don’t believe it.”

Harris stared down at Jake, then at the crumpled stack of disciplinary forms in his hand.

“Well, hell,” he said softly.

He tore them cleanly in half.

England looked gray even when the sun was out.

By early 1944, Jake and the Filthy Thirteen had traded the red clay of Georgia for damp English mud and stone villages where the pubs shut down early and girls laughed in accents the men couldn’t quite mimic no matter how many times Plowo coached them.

They were supposed to behave. There were signs reminding them, there were lectures from officers, there were British MPs and American MPs and a whole formal structure of Allied cooperation.

Jake lasted about a week before he looked at the British rations—watery stew, thin bread, not nearly enough meat for men who’d be jumping out of planes soon—and decided, as he usually did, that the rules were stupid.

He borrowed a battered bicycle, slung his M1 Garand over his shoulder, and pedaled out into the countryside.

If anyone had asked him, he would have said he was just stretching his legs. If they’d followed him, they would’ve seen him ditch the bike in a hedgerow, slip into the woods, and move like he’d been born there. Which, in a way, he had, just a different forest.

The deer in England weren’t that different from the deer in Oklahoma. Rabbits were rabbits anywhere. Pheasants made a lot of noise and not much effort to stay alive if you knew how to move.

By the end of the week, the Filthy Thirteen were eating better than the officers—fresh meat, stews thick enough to stand a spoon in, rabbit roasted over stolen bricks behind the barracks. When game got scarce, Jake improvised, bundling duffel bags of Army TNT and fishing line down to the river at night.

“Sergeant, this is insane,” Wimmer whispered the first time, watching Jake slip a small charge under a tree-snagged bend in the water.

“That’s what they said about putting men in airplanes,” Jake replied. He lit the fuse, stepped behind a boulder, and grinned as the muffled blast turned a stretch of river into a boiling cauldron of stunned trout.

Word got back to the locals, and then higher.

One morning, Jake found himself standing in front of Harris again, only this time there was another man in the office, a tight-lipped British gentleman in a tweed jacket who looked like he’d never been truly hungry a day in his life.

“This is Lord something-or-other,” Harris said, clearly struggling not to grin. “His estate borders the training area.”

Lord Something sniffed. “Your men are poaching my game,” he said. “On my land. With your Army’s weapons. And”—he seemed personally offended by this part—“they are fishing with explosives. The local magistrate is very interested in prosecuting these crimes.”

“That so,” Jake said.

Harris gave him a look that translated to: shut up, for once.

“Sergeant,” the British lord said, “the war effort does not give you license to trample property rights and the laws of this country.”

Jake thought of the rations. He thought of the jump they were about to make.

“With respect, sir,” he said, choosing his words very carefully, “my men are scheduled to jump behind German lines in a few months to blow up bridges and cut rail lines and generally make Adolf Hitler’s life miserable. They’re going to do that on whatever food you feed them. You want us to go in there on boiled cabbage and half a sausage, or on full stomachs?”

The lord’s nostrils flared. “That is not the—”

“What are you going to do?” Jake added, looking from him to Harris. “Send me on an impossible jump into German-occupied territory?”

Harris closed his eyes briefly, shoulders shaking once.

When the British officer left, he turned to Jake.

“You do realize,” he said, “that you get away with this because we have no idea how to threaten you.”

“That’s kind of the point, sir,” Jake said.

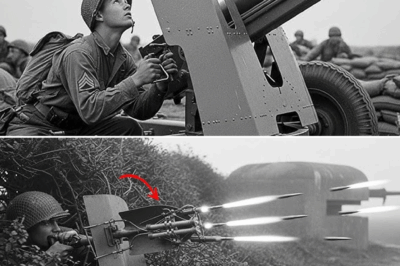

June 5th, 1944, tasted like oil and metal and anticipation.

On the airfield in England, under a low cloud ceiling shot through with a skinny moon, the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne strapped on gear until they looked like men made of canvas and steel.

Jake sat on an overturned crate near the C-47 that would take him to France, carefully painting white streaks across his face. The paint was supposed to cut down on reflection; he didn’t mind that it made him look like something that had crawled out of an old Comanche nightmare.

His hair, raggedly shaved into a Mohawk, stuck up in uneven bristles beneath his helmet. Around him, the Filthy Thirteen sat or squatted, shaving heads, painting their own faces, laughing louder than the rest.

A Stars and Stripes photographer walked past, stopped, stared, and raised his camera.

“What the hell are you supposed to be?” the photographer asked.

“Americans,” Jake said. “The kind they warned your mother about.”

The shutter snapped.

The camera captured white stripes, dark eyes, grim smiles. It captured war paint, Mohawks, bare jerseys with dog tags hanging against sunburned chests. It captured something the brass would later call “morale” and the men would privately call “being too dumb to be scared.”

At 11:47 p.m., Jake’s C-47 engines coughed to life. The men filed in, heavy with equipment: rifles, ammo, grenades, demo charges, rations, all the things men carry when they don’t expect anyone else to help them.

The plane rose into the night.

Over the Channel, the mood was steady, almost calm. Men checked and rechecked static lines, adjusted harnesses, slapped each other’s helmets in rough affection.

Jake sat near the door, feeling the vibration of the plane in his bones, thinking of nothing in particular. When you’ve already decided you’re dead and anything else is extra, there isn’t much left to worry about.

At 1:23 a.m., they crossed the French coast.

German flak opened up like the sky was ripping. 88mm shells and 37mm cannons, tracers stitching red lines through the dark. The plane lurched, metal screaming, men grabbed at the webbing or their stomachs.

“Stand up!” the jumpmaster yelled, voice cracking. “Hook up!”

Jake rose with the others, clipped his static line to the cable overhead, shuffled toward the open door where night and fire waited.

At 1:26 a.m., an 88mm shell found the C-47’s fuel tank.

The world became light and force and noise.

The explosion tore through the fuselage. Fuel ignited. The tail of the plane separated like a toy broken by a careless child. Men were there one instant and gone the next, flung into nothing without chutes deployed.

Jake felt himself ripped backward, felt heat on his face, heard screams that might have been his own. The shock yanked his static line taut.

Then he was outside, falling.

Shrapnel and fire spun around him. A piece of the plane, still burning, tumbled past. The wind clawed at his gear. The chute snapped open above him, jerking his spine like a cruel joke. One panel was on fire. Two others were shredded. He had just enough time to register all three facts before he hit the ground.

He hit water.

The field below, marked on some staff officer’s map as “open,” was flooded. Jake plunged beneath the surface, his pack and gear dragging him down like hands. Mud sucked at his boots. Panic flared for a half second, the animal kind.

Then training and a lifetime of swimming in Oklahoma ponds took over. He cut his harness with numb fingers, shrugged out of his gear, pushed toward light.

He surfaced gasping, spitting water, coughing.

Around him, the night was chaos: burning planes carving orange scars into the sky, parachutes drifting, some on fire, some too low. Gunfire cracked from unseen positions. Men shouted in English and German.

He got his feet under him, waded to a hedgerow, and took stock.

Rifle: submerged, but salvageable. Ammo: wet, but he’d fired in rain before. Legs and arms: hurt, but working. Head: attached.

He reached for the first thing he always reached for: his men.

By dawn, he’d found nine members of the Filthy Thirteen. Four were confirmed dead. The rest were scattered God-knows-where.

Nine men was enough.

He gathered them in a ditch, mud to their knees, faces pale under the war paint.

“Chef Dupon,” he told them, tapping the crude map he’d taken off a dead officer. “There’s a bridge over the Merderet River there. That’s our mission. We take it, hold it, and we keep Jerry from rolling his armor straight into the boys on the beach.”

“Intelligence says how many?” Wimmer asked.

“Two hundred,” Jake said.

“Us?” Joe asked.

Jake looked at them. “Nine.”

Silence. Then Plowo chuckled. “Odds are improving, Sergeant. Could be ten.”

The others laughed because the alternative was something like crying.

“All right,” Jake said. “Move quiet. Use cover. We’re not fighting the whole German army, just whoever’s stupid enough to stand between us and that bridge. Shoot straight. Don’t be heroes. Heroes get statues. We’re here for wreckage.”

They moved.

Through hedgerows and ditches, through fields churned by tank tracks and studded with dead cows, across lanes where burning C-47s lay in pieces, they moved like they practiced back in Georgia: low, fast, quiet.

The Germans around Chef Dupon were not expecting nine men to attack two hundred.

They were expecting chaos. They got it, just not the kind they’d planned.

Jake’s team hit forward positions first: a machine-gun nest here, a mortar team there, always from an angle, never from where a manual said they should. They’d appear, kill, disappear before anyone could respond.

By nine that morning, they’d gathered more strays—paratroopers from other units, lost and disoriented, grateful for someone who seemed to know where the hell he was going. Nine became fifteen, then twenty, then thirty-five by the time they reached the bridge.

The fight for Chef Dupon was ugly and short. The Germans had numbers but no idea where the Americans would hit next. Jake’s men moved like a wolf pack—one element pinning, another flanking, no unnecessary shouting, no wasted shots.

By 11:00 a.m., the Stars and Stripes could have run a picture of Jake and his men standing on the bridge, rifles slung, eyes darting up and down the river.

“Bridge is ours,” Joe said.

“For now,” Jake replied.

At 2:17 p.m., German artillery found them.

The first shells landed wide, throwing up geysers of dirt and river water. The second salvo walked closer. Shrapnel shrieked like angry metal birds. Men dove for cover, clutching at helmets, teeth grinding.

“Dig in!” Jake bellowed over the noise. “We ain’t dying in some Frenchman’s front yard. Get those foxholes deeper!”

By late afternoon, they were as ready as a few dozen men could be under falling steel.

That’s when the American planes showed up.

Four P-47 Thunderbolts, big and beautiful, swept down the river valley at low altitude. The sun glinted off their wings. The white stars on their fuselages shone.

Jake’s heart lifted. He scrambled out of his hole, waving his arms.

“Friendly aircraft!” someone shouted. “Signal panels! Get ‘em out!”

Colored panels went up. Men waved helmets and shirts. Someone fired a flare.

The P-47s banked.

“Hell yeah,” Joe yelled. “They’re gonna strafe those Krauts on the far—”

The first bomb fell short.

The second didn’t.

The bridge they’d spent all day bleeding for disappeared in a geyser of fire and stone. The world turned upside down again. Men were thrown to the ground. The air filled with dust and disbelief.

When the planes roared past, trailing exhaust and American flags, the bridge at Chef Dupon was a jagged, smoking ruin. The Merderet River flowed around its broken supports like nothing had happened.

Jake lay on his back in the dirt, ears ringing, lungs burning with dust. For a moment, he thought he might be dead again. Then he realized he was laughing.

He sat up, coughing, chuckling, unable to stop.

“Sergeant?” Wimmer asked, staggering over. “You hit your head?”

Jake pointed at the collapsed span, wheezing. “They… they bombed their own damn bridge,” he said, incredulous and amused all at once. “We spent all day taking it and Headquarters just… crossed it off the list.”

The men stared at him like he’d lost his mind.

“What now?” Joe demanded. “Mission’s shot. We can’t hold a bridge that ain’t there.”

Jake wiped tears of laughter and dust from his eyes and got serious.

“No bridge means no tanks, at least not here,” he said. “But the Krauts still need this crossing. They’ll try to ford it, throw up pontoon bridges, something. High ground over there”—he pointed to the hill that would, three days later, host a German officer with a white flag—“dominates this whole mess.”

He looked around at his exhausted, hungry men.

“We’re cut off,” he said plainly. “No supplies, no reinforcements, no way home that doesn’t involve a lot of walking through angry Germans. We can either try to sneak out in ones and twos and hope we don’t get picked off… or we can make them pay for blowing up our hard work.”

He jerked a thumb at the hill.

“Dig in up there,” he said. “We’re going to ruin somebody’s week.”

Terrain decides battles. Jake had learned that long before some West Point instructor wrote it on a chalkboard.

The hill above the destroyed bridge had three natural choke points: a narrow road cut between two rises, a game trail along the slope, and a shallow ravine that provided the only covered approach from the west.

He walked the ground with a practiced hunter’s eye, seeing lines of fire and dead space instead of deer trails and rabbit runs.

“Thirty-cal here,” he told Wimmer, marking a spot that covered the road. “Another over there for the ravine. BAR teams: you’re swinging, you plug whatever hole opens up.”

He put his best riflemen in elevated positions where they could see down into the approaches. He told them, “Officers first, NCOs second. You see someone waving their arms and pointing, you shoot him before he can finish the sentence.”

He kept five men in reserve, a little attack dog of a squad whose only job was to go where things looked worst and hit back hard.

When he’d walked the line, talked to each man, checked ranges and sight lines, he called them together one last time.

“All right, listen up,” he said, voice carrying over the murmur of men digging and cleaning weapons. “We’re not getting relieved. Not today. Maybe not ever. No planes are going to drop down out of that sky to save our asses. The only thing coming over that hill is Germans.”

Silence.

“So here’s how it’s going to be,” he went on. “We stay low. We don’t waste ammo. We let ‘em come in close, bunch up on those approaches. Then we show them what thirty-five pissed-off paratroopers can do when you cut their rations.”

Someone snorted. Someone else muttered, “I could go for some grass right now.”

A ripple of rueful laughter broke the tension.

“If you’re scared, that’s fine,” Jake said. “Everybody’s scared. You’re not scared, you’re either lying or stupid, and I ain’t got much use for either. You focus on your sector. You do your job. You trust the man on your left and your right. We hold until we can’t. Then we hold some more.”

He looked at their dirty, skinny faces, at the war paint flaking on his own hands.

“We didn’t come here to surrender,” he said softly.

June 7th dawned gray and damp. German scouts probed the edges of the American positions and fell back, leaving bodies among the hedgerows.

On June 8th, the Germans pushed harder, sending squad-sized elements up the approaches. Each time, the Americans cut them down. Each time, Jake adjusted his line, moved men like a gambler shifting chips, always trying to stay one bet ahead.

By the morning of June 9th, the German officer had his answer to how stubborn these Americans were. He walked up with his white flag, offered surrender, and got Jake’s three options instead.

At 9:14 a.m., he chose option three.

Artillery came first, as it always did. Shells rained down on the forward slope of the hill, tearing trees, gouging earth, making the world an endless series of concussions. Jake’s men hunkered on the reverse slope, behind the crest, out of direct blast. Dirt and rocks rained down on their helmets.

“Stay small,” Jake shouted over the din. “It’s just noise until it’s not!”

When the barrage lifted, the first wave moved in: two hundred German infantry advancing uphill in tight formation, rifles at the ready, machine-guns leapfrogging behind them.

Jake waited.

“Easy,” he murmured, even though most of his men couldn’t hear him from their positions. “Closer. Closer…”

A hundred yards.

“Guns,” he said into the dirt, knowing Wimmer could hear him on the other end of the line. “Now.”

Two Browning M1919 machine-guns opened up like doors slamming. 500 rounds a minute from each barrel, tracers reaching out and touching the German ranks.

Men fell. Men tripped over the men in front of them. The formation wavered, then bunched tighter, making the Americans’ job easier.

Rifle fire joined in, individual cracks punctuating the sustained growl of the Brownings. The BAR gunners waited for the tell-tale silhouette of machine-gun teams trying to set up; when they saw them, they poured fire into them until they toppled backward.

The first wave lasted three minutes.

When it was over, forty German bodies lay on the slopes. The survivors crawled, stumbled, or ran downhill, leaving rifles, helmets, and pieces of themselves behind.

The Americans ducked back, checked weapons, swapped belts, counted ammo.

“You all right?” Jake shouted down the line.

“We’re fine,” someone called back. “They’re the ones having a bad day.”

At 11:00 a.m., mortars joined the party.

Rounds popped and whistled, then exploded along the crest. Bark flew off trees. A shard of hot metal sliced a groove in Jake’s helmet, ringing his ears. He blinked, swore, spat blood where he’d bitten his tongue.

“Still here,” he muttered.

The second wave came in under the falling mortar shells, trying to use the explosions as cover. They fared no better. The Americans had learned the rhythm of the barrage, the pattern of the German advance.

Again: machine-guns, rifles, BARs. The Germans fell, crawled, died.

Around midafternoon, the Germans got serious.

Artillery, heavier this time. The kind that made the earth jump. Jake huddled low, feeling each blast in his chest. He could hear the men cursing, praying, laughing hysterically, sometimes all three.

When the guns stopped, he knew something worse was coming.

He was right.

Two tanks rolled into view on the road below: squat, thick-armored beasts with 75mm main guns and coaxial machine-guns. Panthers, maybe. Maybe something older. The exact model didn’t matter. What mattered was that Jake had no bazookas, no anti-tank mines, not so much as a Boy Scout with a satchel charge.

“Aw, hell,” Joe said from his foxhole, peering through binoculars. “They brought the big boys.”

“Let ‘em come,” Jake replied.

The tanks ground up the narrow road, infantry clustered behind them, using their hulks as cover. The armored beasts fired as they moved, shells slamming into the hillside, chewing up the forward slope.

Jake watched their arcs.

Too low.

The angle of the hill meant the tanks couldn’t elevate their guns high enough to hit the American positions on the reverse slope. They were pounding empty ground while the men who’d kill them watched from above.

“Machine-guns,” Jake called. “Forget the tanks. Hit the cherry stems.”

His gunners swung their barrels, ignored the looming armor, and focused on the infantry clustered behind.

The first burst caught a group of Germans still in the tank’s shadow, mowing them down. The rest scattered, instinctively moving away from the hulks that had previously protected them.

Without infantry to screen them, the tanks were alone in a narrow defile, exposed to—if not the Americans’ fire—then to the limits of the terrain. They couldn’t advance off the road without risking bogging down. They couldn’t pivot without exposing weaker armor. They couldn’t hit what they needed to hit because the hill didn’t care about their engineering.

For half an hour, the tanks barked at empty air and soil while the Americans tore up every German foot soldier foolish enough to try to support them.

Finally, the tanks backed down the road, clanking in what looked suspiciously like frustration.

The sun slid westward. Smoke hung low over the hill.

German casualties climbed past a hundred dead, many more wounded.

American casualties: zero.

They held through the night, trading watches, chewing on grass and strips of leather, rationing water like misers. Men shivered in their foxholes and whispered about home, about pancakes and real coffee and girls who’d said they’d wait.

On June 10th, with the morning mist still clinging to the ground, someone on the eastern ridge shouted, “Movement! American!”

Every man on the hill turned to look.

From the tree line, dirty shapes materialized, moving cautiously, weapons at the ready. For a sick heartbeat, Jake thought it might be another attack. Then he saw the distinctive helmet shape, heard voices calling in flat Midwestern English.

“82nd!” someone yelled. “It’s the Eighty-second!”

They came up the hill in ones and twos, eyes wide at the carnage on the slopes, the burnt patches, the shell craters. At the top, an officer in a filthy uniform found Jake leaning on his rifle.

“Who’s in charge here?” the officer asked.

Jake straightened out of habit. “That’d be me, sir. Sergeant McNiss.”

The officer looked around at the ragged paratroopers, at the layered positions, at the thin line of tired faces holding rifles that hadn’t shaken even once.

“How many casualties?” he asked.

Jake shrugged. “Couple twisted ankles. One fella nicked his thumb cleaning his Garand.”

The officer scowled. “I’m not in the mood for jokes, Sergeant. I asked for your casualties.”

Jake met his eyes. “Zero, sir.”

The officer stared.

“How many Germans?” he asked quietly.

“Last I walked the hill last night, I counted a hundred twenty-seven that won’t be writing home,” Jake said. “More wounded. They left some down there. We couldn’t get to all of ‘em.”

The officer shook his head slowly, then looked back down the hill, as if trying to reconcile the numbers with the ground.

“You boys need anything?” he asked finally.

Jake’s stomach chose that moment to growl loud enough to be heard.

“Well,” he said, deadpan, “if you got something that used to be a cow, we’re tired of eating grass.”

You would think, hearing that story years later in some quiet VFW hall, that the Army would have lined up medals for Jake. Silver Stars at least. Maybe a piece of ribbon with the word “Honor” in it.

Instead, they gave him a Bronze Star, a handshake, and new orders.

There was always another impossible job.

By December 1944, Jake had survived six months in France. The Filthy Thirteen were down to four original members. The rest were dead, wounded, or scattered to other units.

The next job came when the German army launched one last desperate punch through the Ardennes, catching the Allies off guard. They called it the Battle of the Bulge later, on maps and in books. At the time, it felt a lot simpler: too many Germans, too much snow, not enough of anything else.

In the town of Bastonia, Belgium, the 101st Airborne and elements of other units found themselves surrounded: eleven thousand Americans cut off, no land route for supplies, no way out.

“Pathfinders,” someone at headquarters said. “We need pathfinders.”

Pathfinders were the men who jumped first, before the main drop, to set up radio beacons and mark drop zones. They went in small, light, and usually alone.

They asked for volunteers.

Jake raised his hand because that’s what he’d signed up for—dangerous, stupid missions that made sense only if you assumed someone at the top had a plan.

On December 18th, at 3:47 a.m., he and nine other Pathfinders climbed into C-47s again.

The weather was worse than anyone wanted to admit: heavy fog, low clouds, ice on the wings, visibility measured in curse words. German anti-aircraft batteries bracketed the approaches to Bastonia like they’d read the same manuals the Americans had.

The pilot looked back at the men in the belly of the aircraft, expression pale.

“This is suicide,” he told the jumpmaster. “I can’t see the town. I can’t see the ground. I’m flying on instruments and guesswork.”

The jumpmaster looked at Jake.

“You still in?” he asked.

Jake shrugged. “I’ve survived worse,” he said. “Let’s not break the streak now.”

He jumped into fog at a thousand feet with no idea where the ground was, where the lines were, or whether there would be anything under him when the chute snapped open.

For a moment, it was like falling through milk. No stars, no sense of up or down, just the hiss of air and the faint, distant thud of artillery.

Then he dropped through the cloud layer, and Bastonia was there below him: a shattered little town ringed by flashes and shell bursts, full of men in American uniforms looking up in disbelief as paratroopers materialized out of the fog like ghosts.

His chute flared. He hit hard, rolled, came up with his rifle half-raised.

An American sergeant in a heavy overcoat stared at him.

“Who the hell are you?” the sergeant demanded.

“Pathfinders,” Jake said. “Where ain’t the Germans?”

The sergeant gestured in a slow circle. “Pick a direction.”

Eight of Jake’s ten Pathfinders made it into the town. Two had gone down outside the perimeter and didn’t answer calls. Jake wrote their names down in the private list he kept in his head, the one he visited at night when he couldn’t sleep.

He split the survivors into two teams: one for the east side of town, one for the west. Each team set up radio equipment—antennas, beacons, homing devices—and started bouncing signals between them to make it harder for German artillery to triangulate.

At 10:17 a.m., Jake keyed his radio.

“Bastonia to Allied command,” he said. “Bastonia to Allied command. Americans still holding. Request immediate resupply drop. Priority: ammo, medical, food, in that order.”

Static hissed for a breathless second. Then a voice crackled back, faint but there.

“Bastonia, this is Allied command. Copy your situation. Weather is negative. Flak is heavy. We’ll send what we can.”

At 11:34 a.m., the first C-47 came in over the town.

It was just one plane, flying low and slow through clouds that wanted to eat it. German flak clawed the air around it. The pilot held his nerve, held the line Jake’s beacons gave him.

Bundles tumbled out of the back: canisters on parachutes, bundles of crates, everything strapped and marked.

Some drifted outside the perimeter and were lost. Most fell where they were supposed to: into streets and fields held by cold, hungry Americans who looked up like men seeing water after a week in the desert.

“Tell that pilot he’s got a drink waiting in heaven,” one infantry lieutenant muttered, hauling a crate of ammunition into cover.

Jake called in another drop. Then another. Then another.

For the next twenty-four hours, those morse-code bleeps and crackling radio calls were the thin line between the 101st and catastrophe.

“Bastonia to command. Drop successful. Shift three hundred yards west, repeat pattern.”

“Copy, Bastonia. Godspeed.”

Planes came in singly or in pairs. Some made it, some didn’t. One C-47 took a flak burst in the wing, wobbled, dropped its load, and managed to limp back into the clouds trailing smoke. Another took hits right over the drop zone, exploded, and rained burning aluminum and courage down onto the town.

Jake felt every loss contract behind his ribs, but he didn’t stop. There wasn’t time to mourn each metal coffin. There was only the math: drops completed, supplies received, guns still firing.

By December 20th at 10:17 a.m., he’d coordinated 247 successful resupply drops. 247 planes, thousands of pounds of ammunition, food, bandages, whiskey in hidden bottles, letters from home taped to boxes.

The men on the ground kept fighting. The town held.

When Patton’s Third Army finally punched through the German lines and reached Bastonia on December 26th, they found men in ragged uniforms, shooting from foxholes half filled with snow, eating better than expected and using ammunition like water thanks to a handful of pathfinders who’d jumped into a surrounded city because someone had to.

There was no medal for that, not then. Pathfinder operations were classified. Files were stamped, locked away. No one outside a small circle of men in windowless rooms knew what Jake had done.

Jake didn’t care much. He’d kept eleven thousand American soldiers from starving or running dry in their rifles. That was enough.

After Germany surrendered in May of 1945, the 101st stayed in Europe as part of the occupation.

They found Herman Göring’s abandoned castle, all marble halls and stolen paintings, wine cellars and stables full of racehorses that had once belonged to people now dead or missing.

The Army put guards on the place. The guards were supposed to keep enlisted men from looting. Jake considered looting a harsh word for “redistributing Nazi luxuries.”

One night, he and a handful of paratroopers threw a party. They drank Göring’s expensive liquor out of tin cups and rode his horses bareback around the courtyard, whooping like rodeo clowns.

During the chaos, Jake met a German girl named Amelia in the kitchen, trying to salvage something like normal life out of the wreckage. She told him, in halting English, that her father had been the leader of the local Hitler Youth chapter.

“That so?” Jake said, pouring coffee into a mug that probably belonged in a museum. “Well. Nobody’s perfect.”

He thought it was hilarious. The Army did not.

They shipped him home to Arkansas for medical treatment not long after, citing “fatigue” and “chronic minor injuries.” Which was Army talk for: this man has been shot at too many times and keeps finding trouble in his off hours.

At the hospital, he got in one last scrap with military police after one of them decided wounded paratroopers shouldn’t be allowed to drink beer on the steps.

“Once I’m a civilian,” Jake told the MP commander afterward, eyes flat, “I’ll come back and we’ll settle this properly.”

Someone in a higher office read that line and decided, finally, that the cost-benefit on keeping Jake McNiss in uniform had tipped the wrong way.

They discharged him. Honorable.

Three years, five months, twenty-six days of service. Four combat jumps. Hundreds of confirmed kills. Multiple missions that staff officers would give impressive names in after-action reports.

Never promoted past private on paper, no matter how many times men had called him “Sergeant” on battlefields because paper didn’t mean much out there.

They handed him a train ticket and a small stack of papers and told him he was a civilian again.

Civilians didn’t wake up gasping in the middle of the night, tasting dust and cordite, hearing the ghost-echo of artillery.

Civilians didn’t see bridges burning every time they closed their eyes. They didn’t hear P-47 engines Christmas-caroling in their skull. They didn’t feel like they’d left most of themselves on a hill above a destroyed bridge or in a foggy Belgian town.

Jake did.

At first, he tried to pretend it was just nerves. Back home in Oklahoma, the sky was big and open, the fields flat and honest. His parents were older. Some of his siblings had moved away, some had kids of their own. The world had a vacuum where the war had been.

He got a job at a refinery, then lost it after he almost choked a supervisor for shouting at a kid who’d spilled oil. He tried working construction. The noise made him jumpy.

So he drank.

Whiskey quieted the noise for a while. It blurred the edges of the nights. It made the faces in his dreams less sharp, at least until it didn’t.

By 1951, the habit had its hooks in him like shrapnel. He woke up most mornings with his head pounding, mouth dry, and a vague sense of having survived another battle he couldn’t remember.

One wet night outside Ponca City, he wrapped his car around a telephone pole.

He’d been doing sixty on a road that was built for forty, the world sliding pleasantly around him. A deer—or maybe nothing at all—flashed in his headlights. He jerked the wheel. The car skidded, hit mud, left the road, and met the pole with the sick crunching sound of metal giving up.

He woke up three days later in a hospital bed, skull fractured, ribs broken, lungs wheezing like rusted bellows.

A doctor stood over him. “You should be dead,” the man said bluntly.

Jake stared at the ceiling tiles, counting them like he’d once counted artillery shells.

He thought of the plane exploding over Normandy. He thought of German shells walking up a hill toward his foxhole and stopping one crater shy. He thought of flak bursts around C-47s in Bastonia, of burning planes falling just short of his beacon. He thought of sliding on ice in a Belgian street and somehow not catching the bullet meant for the man behind him.

He thought: How many times does a man get to pull this trick?

That night, lying in a hospital bed with pain chewing on his bones, Jake had what some people later would have called a religious experience. He didn’t see angels. No voice boomed from the ceiling.

He just realized, with a cold clarity, that if he kept going the way he was going, he was going to die in a ditch in Oklahoma with a bottle in his hand, and that would make a mockery of every man who hadn’t made it home from Chef Dupon or Bastonia.

He decided that maybe all those close calls meant something.

The next day, he told the nurse he was done with alcohol.

She snorted. “I’ve heard that before,” she said.

He smiled faintly. “Yeah,” he said. “But the war hadn’t tried to kill them first.”

He quit drinking that week. He never touched a drop again.

Some people find God in church pews. Jake found Him in the arithmetic of survival: the odds he’d beaten, the friends who hadn’t, the fact he was still breathing when so many better men were not.

If someone asked him later, he’d shrug and say, “Figured if Somebody went to all the trouble to keep me alive, I ought to start acting like it.”

Six months later, he met Mary Catherine at a church picnic.

She was an Oklahoma girl with clear eyes and a stubborn streak that could stop a tornado. She knew he’d “seen action” in the war—every man her age had, in one way or another—but he never told her the details, and she never pushed.

He liked that about her. She liked that he worked hard, listened more than he talked, and didn’t drink even when other men did.

They got married with a small ceremony and a big potluck. Jake wore a suit that felt stranger than any uniform he’d ever been in. His family came. Some of the Filthy Thirteen sent letters or gifts from wherever they’d ended up.

They had three children over the next handful of years: two boys and a girl.

When his oldest son asked, at age six, “Daddy, did you shoot bad guys in the war?” Jake looked at his small, earnest face and thought about how to answer.

“I was a paratrooper,” he said finally. “My job was to keep my friends alive and get home so I could be your daddy.”

The boy considered this, nodded solemnly, and went back to playing with his wooden airplane.

Jake got a job at the Ponca City Post Office. It was steady work: sorting mail, selling stamps, guiding grandmothers through the mysteries of money orders. It kept his hands busy and his days predictable.

He liked that the worst thing that could happen in a shift was a lost package or a customer who insisted their letter to Boise should have arrived yesterday.

His coworkers knew he’d been in the war. Everyone of that generation had some connection. But they didn’t know he’d once held a bridge against seven hundred Germans with thirty-five men and zero casualties. They didn’t know he’d jumped into Bastonia and called down manna from metal birds.

They just knew that Mr. McNiss was steady, polite, and very good at carrying heavy sacks without complaining.

On Sundays, he went to church with his family, sat in the same pew, sang the hymns in a rough baritone. He coached Little League, teaching kids to keep their eye on the ball and their mouth shut when things didn’t go their way.

He never marched in parades. He never joined the color guard on Memorial Day. The uniforms in his closet stayed on their hangers, growing dusty.

“Daddy, why don’t you wear your medals?” his daughter asked once, having found the little box in a drawer while looking for tape.

He closed the drawer gently.

“Because war isn’t something to brag about,” he said. “It’s something you get through. Those men they gave medals to? Most of ‘em would’ve traded the metal for another day with their buddies.”

She frowned, not quite understanding, and he was glad. There were some things he’d come to believe children didn’t need to understand.

He didn’t lie about his service. He just… edited. Smoothed out the edges. Left out the part where he’d laughed while his own Air Force bombed his bridge. Left out the part where he’d told a German officer to go to hell with perfect tactical reasoning.

The nightmares never fully stopped. Some nights, Mary Catherine woke to find him sitting on the edge of the bed, staring at the wall, jaw clenched.

“You all right?” she’d ask.

“Yeah,” he’d say. “Just walking a hill I ain’t on anymore.”

She’d put a hand on his shoulder. He’d lie back down. The house would settle around them like a foxhole, warm and safe.

As the years went on, the kids grew up. They left home, got married, had kids of their own. Jake became a grandfather before he felt ready, then settled into the role like he’d settled into most things: quietly, with more competence than he let on.

In the post office, younger workers started taking over the heavy lifting. He moved slower, but his hands were still sure when he counted out stamps or sorted envelopes.

If you’d walked into that post office in, say, 1980, you would have seen an elderly man behind the counter with thinning gray hair and deep lines at the corners of his eyes. You might have thought he’d spent his life in small-town routines.

You would not have guessed that the same man had once jumped into flak over Normandy with a burning parachute, or that he’d stood on a hill in France and turned seven hundred German soldiers into a bad memory with thirty-five men who were tired of eating grass.

He liked it that way.

He lived quietly, loved his wife, spoiled his grandkids, paid his bills, went to church, and showed up when people needed help moving furniture or fixing a fence.

He’d killed a lot of men. He’d watched friends die. He’d been very, very good at doing things no human being should be good at.

For the rest of his life, he tried to be good at simpler things.

In 2013, at age ninety-three, Jake McNiss lay in a hospital bed for the last time.

His hair was thin and white. His face had the soft collapse that comes when muscles finally admit they’re finished. But his eyes were still the same storm-cloud gray.

Mary Catherine held his hand. Their children and some of their children gathered around, murmuring, shifting, overwhelmed by the slow-motion magnitude of losing the man who’d always been there.

“Daddy,” his daughter whispered. “You all right?”

“I’m fine,” he said, because that’s what he always said. His voice was papery, but there was still a thread of humor in it. “Doc says I might have to sit out the next war, though.”

A nurse chuckled despite herself.

One of his grandsons, a teenager with a buzz cut, stepped closer.

“Grandpa,” he blurted, “did you really jump out of airplanes in the war?”

Jake looked at him, at the haircut that echoed his own long-ago youth.

“I did,” he said.

“Were you scared?”

“Every time,” Jake said. “That’s how you know you’re still paying attention.”

The boy bit his lip. “Mom says you were some kind of hero. Held off a whole German army or something. Is that true?”

Jake’s eyes flicked to his daughter. She flushed.

He considered lying. He considered deflecting.

In the end, he decided the boy was old enough for one truth, if not the whole carnival.

“My unit got into some scrapes,” he said. “We did our jobs. We got lucky more than once. The heroes, far as I’m concerned, are the ones who didn’t come home to sell stamps.”

He squeezed the boy’s hand with what little strength he had.

“If you ever end up in a spot where someone’s telling you to do something dumb that’s going to get people hurt,” he said softly, “remember: obedience and discipline ain’t the same thing. Do the job, not the nonsense.”

The boy nodded, eyes shining.

That night, after the visitors left, Jake lay half awake, listening to the beeps and sighs of hospital machines.

He walked the hill at Chef Dupon in his mind, checked his lines, heard again the soft rasp of earth on shovels, smelled the mix of sweat and cordite.

He walked the streets of Bastonia, felt snow under his boots, heard the drone of approaching C-47s, the chatter of flak.

He visited each place he’d left a piece of himself, rolled them between mental fingers like old coins.

He thought of the German officer with the white flag, of the calm offense in his voice when he’d called surrender logical.

He thought of the mess hall at Fort Benning, of a pat of butter melting into someone else’s grits and a young man deciding that some things were worth punching over.

He thought of Lord Something’s outraged face as he complained about poached pheasants while boys practiced dying for his freedom.

He thought of his men, the Filthy Thirteen, most of them gone now, their names carved in stone or forgotten by everyone but men like him.

And he thought of that line he’d always claimed as a joke, the one he’d toss off when people asked why he’d volunteered.

“I wanted to kill Nazis, eat breakfast, and go home.”

He’d done the first part more thoroughly than anyone should. He’d done the second in too many countries, sometimes chewing grass under artillery fire. He’d spent the last forty years doing the third in the most ordinary, extraordinary way possible: selling stamps, coaching kids, loving his family.

Three items on a list. All checked off.

That felt like enough.

He let out a long breath, like a man at the end of a long march taking off his pack.

Somewhere far away, artillery echoed, but it was faint now, like a storm on another horizon.

The monitors hummed and blinked. His heart, which had pounded on too many drop zones, finally decided it had put in its time.

The nurses found him with a small smile on his face.

The obituary in the local paper read:

JACOB E. MCNISS, 93, of Ponca City, passed peacefully surrounded by family. He was a devoted husband, father, and grandfather, a retired postal worker, and a veteran of the Second World War.

It didn’t say anything about the hill. Or the bridge. Or the fact that exactly seventy years earlier, the Army had tried and failed to kick him out eight times before realizing the only useful thing to do with a man like that was to point him at impossible jobs and get out of his way.

People who’d bought stamps from him shook their heads, surprised he was gone.

Somewhere in a box in an attic, a small stack of medals tarnished slowly.

In a field in France, grass grew tall over a hill that remembered a few loud days in June. In a Belgian town, old men who’d once been freezing boys still told stories about the night angels fell out of the fog with radio beacons and stubbornness.

And if you listened hard enough, on some quiet American morning when the sky was the color of faded photographs, you might have sworn you heard a rough Oklahoma voice say, with that dry humor:

“Kill Nazis. Eat breakfast. Go home. That was the deal.”

He’d kept his end.

THE END

News

CH2 – This 19-Year-Old Was Manning His First AA Gun — And Accidentally Saved Two Battalions

The night wrapped itself around Bastogne like a fist. It was January 17th, 1945, 0320 hours, and the world, as…

CH2 – The German Boy Who Hid a Shot-Down American Pilot from the SS for 6 Weeks…

The SS officer’s boot stopped six inches from the boy’s nose. Fran Weber stood in the barn doorway with his…

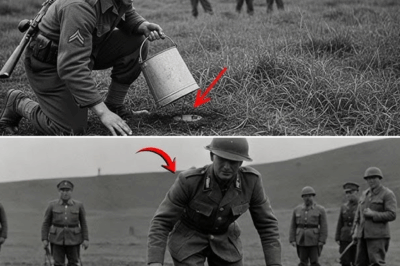

How One Private’s “Stupid” Bucket Trick Detected 40 German Mines — Without Setting One Off

The water off Omaha Beach ran red where it broke over the sandbars. Corporal James Mitchell felt it on his…

Germans Couldn’t Believe This “Invisible” Hunter — Until He Became Deadliest Night Ace

👻 The Mosquito Terror: How Two Men and a Radar Detector Broke the German Night Fighter Defense The Tactical Evolution…

How One General’s “IMPOSSIBLE” Promise Won the Battle of the Bulge

The Impossible Pivot: George S. Patton, the 72-Hour Miracle, and the Salvation of Bastogne I. The Storm of Despair in…

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

🎯 The Unconventional Weapon: How John George’s Civilian Rifle Broke the Guadalcanal Sniper Siege Second Lieutenant John George’s actions…

End of content

No more pages to load