Part I

The engines of the B-17 bomber Ye Olde Pub trembled against the December wind as it climbed through the thin gray skies over Bremen, Germany. Inside the fuselage, frost clung to metal panels and breath turned to mist. Ten young Americans sat in that flying fortress, their eyes sharp, their hearts thundering in rhythm with the four Wright Cyclone engines pushing them toward enemy territory.

Second Lieutenant Charlie Brown, just twenty-one, sat in the pilot’s seat, his hands steady on the yoke. His knuckles were pale in the cold, but his grip didn’t waver. This was his first mission as lead pilot. Nerves churned beneath the calm surface he forced himself to maintain.

The intercom crackled.

“Approaching target zone,” came the voice of the navigator, 1st Lt. Al Sadok.

Charlie nodded and checked his instruments. “Copy that. Let’s make this clean, boys. Drop and get the hell out.”

Below them stretched the industrial sprawl of Bremen, a gray patchwork of smoke, factories, and anti-aircraft batteries. The Luftwaffe had teeth here. Everyone knew that. The crew of Ye Olde Pub had joked about it during breakfast that morning—forced bravado masking dread. No one laughed now.

Charlie looked over at his co-pilot, Lt. Spencer Luke, whose jaw was tight, his eyes forward. Behind them, the radio operator checked his gear, and the tail gunner muttered a quiet prayer under his breath.

The bomb bay doors opened. The wind screamed into the cabin.

“Bombs away!” The bombardier’s shout was barely audible over the engines. Seconds later, the B-17 lurched as its deadly load dropped toward the smoking city below.

Then came the flak.

Explosions erupted around them, black puffs of death. The aircraft jolted violently; fragments of shrapnel shredded through the fuselage. The smell of burning metal and hydraulic fluid filled the air.

“We’re hit!” shouted the engineer. “Engine number two’s losing pressure!”

Charlie gritted his teeth and fought the controls. The bomber shuddered and dipped.

“Feather number two!” he barked.

“Feathering!” came the reply, but the response was followed by another explosion.

A flak shell tore through the nose. The blast sent the bombardier flying backward, his chest soaked with blood. The front plexiglass shattered, letting in an icy gale. Charlie’s ears rang; his face stung from splinters of glass.

He heard someone scream behind him. The right wing was on fire.

“Jesus Christ,” Spencer muttered, looking out the window. “We’re sitting ducks.”

“Stay with me,” Charlie ordered. “Keep us level.”

More flak. More damage. The bomber staggered through the air, a wounded bird bleeding smoke.

Then came the fighters.

Messerschmitt Bf 109s sliced through the sky—sleek, silver, deadly. The first strafing run tore across the bomber’s tail. Bullets ripped through aluminum, punched holes through the fuselage, shredded oxygen lines. The right waist gunner, Sgt. Alex Yelesanko, fired back furiously, his twin .50 cals spitting fire.

Two more Bf 109s swooped in. One came straight for the nose. Charlie jerked the yoke, but too late—the German guns chewed through the fuselage. The radio operator went down screaming.

“Tail gunner’s out!” someone shouted.

“No, he’s alive! He’s hit bad but breathing!”

The oxygen system was gone. They were freezing, gasping in the thin air. The altimeter needle dropped—14,000 feet… 13,000… 12,000.

Charlie fought the controls, his vision blurring. “Hold her together!”

The enemy fighters peeled off one by one, assuming the bomber would crash. The Ye Olde Pub had fallen far behind its formation—alone, limping, losing altitude.

Charlie looked around. The navigator was bleeding. The bombardier was unconscious. Only three of the ten men could still move.

He thought of home—of the Appalachian hills where he grew up, of his mother’s kitchen, of the way the sunlight hit the front porch when he was a kid. He thought of how young they all were. Too young.

“We’re not dying over Germany,” he whispered.

He turned the bomber toward the North Sea, toward home.

The instruments were erratic; half the gauges didn’t even register. Frost crept along the shattered windows. The tail section was barely attached.

“Spence,” Charlie said quietly, “if we make it back, drinks are on me.”

Spencer managed a weak grin. “You’re damn right they are.”

The B-17 limped westward, alone in the vast gray sky. Then, through the shattered glass, Charlie saw it—a flash of silver catching the morning sun. A single aircraft rising toward them.

“Oh no…” Spencer’s voice was grim. “He’s coming back to finish us.”

The Messerschmitt 109 approached fast, sleek and deadly, like a hawk descending on a crippled sparrow. The black cross on its fuselage glinted in the light.

Charlie reached for the trigger on the control yoke, ready to fire what little ammo they had left. The B-17’s guns were jammed or destroyed, but instinct took over.

The German fighter slowed as it came alongside. Charlie’s breath caught. The enemy plane drew parallel—so close he could see the pilot’s face through the canopy.

For a long, surreal moment, they just stared at each other.

The German pilot looked to be in his late twenties, maybe early thirties. Blond hair under a leather cap, eyes an intense, piercing blue. His aircraft bore victory marks—many of them. This was a killer.

But his guns didn’t fire.

He tilted his head, studying the wreck that was Ye Olde Pub. He could see the torn fuselage, the holes big enough to crawl through. He saw the dead and wounded men inside, the pilot’s pale face streaked with blood.

Then, astonishingly, the German raised one gloved hand and motioned downward—trying to signal them to land.

Charlie stared, confused. Land? In Germany? That would mean capture—prison camps, interrogations.

“No way,” he muttered, shaking his head. He pointed west.

The German frowned, then nodded once. To Charlie’s disbelief, the Messerschmitt pulled in close again—so close their wingtips almost aligned—and began flying beside them.

“What the hell is he doing?” Spencer whispered.

Charlie didn’t answer. He didn’t know.

Below them, German anti-aircraft batteries tracked the bomber. The flak gunners saw the American craft, prepared to fire—but then noticed the German fighter escorting it. They hesitated. Surely it was being captured or guided.

For the next ten minutes, the two planes—enemy and ally—flew together across northern Germany. Every second felt like a lifetime.

Inside Ye Olde Pub, the surviving crew watched through shattered windows as the German fighter held formation. None fired. None spoke.

At last, as the coastline appeared ahead—the icy expanse of the North Sea glittering below—the German pilot turned his head once more. He met Charlie’s eyes through the glass. Then he raised his hand in a crisp salute.

Charlie, heart pounding, returned it.

The Messerschmitt rolled gently to the right, peeled away, and vanished into the clouds.

Silence filled the bomber.

Spencer exhaled slowly. “Did that just happen?”

Charlie nodded, unable to speak. His throat was tight.

It took everything they had to keep the Ye Olde Pub airborne across the water. The engines coughed and sputtered, the airframe groaned. Somehow—by miracle or mercy—they made it to the English coast.

RAF Seething airfield scrambled emergency crews when they saw the wreck limping in. Fire trucks raced along the runway as Charlie brought the bomber down. The landing gear locked at the last possible second. The plane hit the tarmac hard, skidding to a halt in a shower of sparks.

The crew stumbled out—bloodied, frostbitten, barely conscious. One man was dead. Eleven were alive.

The ground crew gaped at the B-17. There were holes the size of doors in the fuselage. One propeller was gone. Half the tail had been shredded away. No one could believe it had flown.

Later, during the debriefing, Charlie told his commanding officers what had happened—the German fighter who had escorted them to safety.

The reaction was immediate and cold.

“Never speak of this again,” one officer said flatly. “Not to the crew, not to anyone.”

Charlie frowned. “Sir, he saved us. He could’ve killed us all, but he didn’t.”

The officer’s jaw tightened. “If word gets out that German pilots are showing mercy, it could create confusion. Sentimentality. We can’t afford that. You understand?”

Charlie hesitated. “Yes, sir.”

But he didn’t understand. Not really.

That night, alone in his bunk, he thought of those blue eyes staring at him through the shattered glass. Of that salute. Of the choice that had spared ten men.

And in the silence, a question took root in his mind—one that would stay there for forty years.

Who was he?

Part II

When the war ended, Charlie Brown was twenty-three years old and already an old man inside.

He had flown more missions after that December day, but none like Bremen. None that would etch themselves so deep into his bones. By the time he completed his combat tour, he’d seen enough destruction for ten lifetimes. His hair had thinned, his hands trembled when the engines roared, and he’d learned to stop talking about fear.

He went home to West Virginia that summer, stepping off the train into a world that had moved on without him. The hills were green, the air thick with honeysuckle and coal dust. His mother cried when she saw him. His father, stoic as ever, just nodded and said, “You did your part, son.”

Charlie smiled and tried to believe that was enough.

But the nights were another story. The war followed him home. The sound of engines in the distance could freeze him mid-step. When a truck backfired, he ducked for cover before he realized where he was. He dreamed of falling—always falling—over a gray sea under a frozen sky.

And sometimes, in that space between sleep and waking, he saw the German pilot again.

Those blue eyes behind glass. The salute.

Then the crash of gunfire, the whine of engines, and he’d bolt upright, drenched in sweat.

He didn’t talk about it. Not to his parents, not to his friends, not even to the men who’d been with him on Ye Olde Pub. They all had their own ghosts to wrestle. When they gathered once, a few years later, they spoke of the war the way old football players talk about high school—loud and laughing, careful never to look too deep.

Charlie never told them the truth—that a German pilot had saved them.

He’d been ordered not to.

And in time, silence became habit.

In 1949, restless and searching, Charlie joined the newly formed U.S. Air Force.

He needed the sky. The sound of engines calmed him more than silence ever did. He became a career officer, known for his discipline and quiet intelligence. His colleagues respected him, even if few ever got close enough to call him friend.

He married a nurse named Eileen, who loved him with patient kindness. They had two children—first a daughter, then a son. On weekends, Charlie mowed the lawn, grilled burgers, and pretended the world made sense.

But at night, Eileen sometimes found him sitting in the dark, staring out the window.

“You okay?” she’d whisper.

He’d nod. “Just thinking.”

She never pressed.

He served in Laos and Vietnam during the 1960s, not as a combat pilot this time but as an Air Force adviser and later a State Department attaché. The jungles and humid air reminded him that war never really ends—it just changes shape. He saw the same young faces he’d once known, only the names were different.

When he retired in 1972, Charlie and Eileen moved to Miami, Florida, chasing sunlight and quiet. He started tinkering with inventions—tools, gadgets, anything mechanical. He liked working with his hands. The precision gave him peace.

To neighbors, he was just a polite man with kind eyes and a faint Southern accent. They didn’t know about the war medals tucked away in a drawer. They didn’t know about the nightmares.

His daughter, Susan, once said that sometimes, in the middle of the night, she’d hear him cry out—brief, choked, like a man drowning. By the time she’d reach his room, he’d be awake, eyes wide and far away.

“Bad dream, Daddy?” she’d ask.

He’d smile weakly. “Just a dream, honey. Go back to bed.”

But it wasn’t just a dream. It was the same memory over and over—the crippled bomber, the flak, the German pilot alongside them. The look they shared, brief and impossible, before he disappeared into the clouds.

And always, the same question that haunted him more as the years passed:

Who was he?

At reunions of bomber crews, Charlie sometimes thought of telling the story. He’d start to, then stop. The warning from his commanding officer still echoed: Never speak of this again.

The war had been brutal. There was no room for sentiment in a world that demanded enemies. You couldn’t tell stories about mercy when people were still counting graves. But the longer Charlie lived, the less that warning made sense.

He’d seen too much cruelty to believe in black-and-white morality. He’d seen what hatred did to men. And the memory of that German fighter—the one who had looked at him, seen his broken plane and dying crew, and chosen not to pull the trigger—was the one thing that still reminded him there had been humanity left in the world, even then.

By the early 1980s, Charlie was in his sixties. His children were grown, his hair white, his posture a little stooped. He’d buried friends, lost his wife to illness, and retired twice. Yet still, that question lingered. It wasn’t just curiosity—it was an ache.

Sometimes he’d catch himself staring at the sky, whispering, “Are you still out there, whoever you were?”

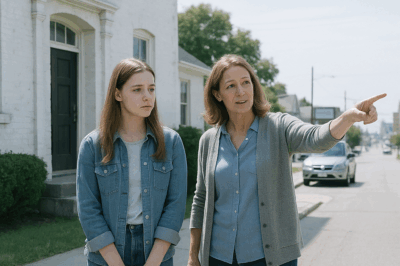

In 1986, Boeing hosted a reunion called The Gathering of the Eagles in Boston—a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the B-17 Flying Fortress. Veterans from across the country attended. Charlie almost didn’t go. He told his daughter he was too old for nostalgia. But she insisted.

“Dad,” she said, “you owe it to yourself.”

He arrived in his best blazer, medals polished but discreet. The room was a blur of laughter, old uniforms, and gray-haired men clapping each other on the back. Models of bombers hung from the ceiling. Photographs of smiling crews lined the walls—men frozen in time before the world took their innocence.

When the microphone passed to him, Charlie hesitated.

“Lieutenant Colonel Charlie Brown,” the announcer said. “Lead pilot of Ye Olde Pub, 379th Bomb Group.”

Applause. Whistles. He nodded politely and stepped forward.

Someone asked, “What was your most memorable mission, Colonel?”

He froze. For forty-three years, he’d avoided that question. But surrounded by men who understood the sky—the fear, the loss, the strange brotherhood of it—something in him cracked.

He took a breath.

“Well,” he said slowly, “there was one over Bremen, December 1943…”

And for the first time, Charlie told the story.

The crippled bomber. The German ace who appeared on their wing. The silent escort through enemy skies. The salute.

When he finished, the room was silent. Then the questions came all at once.

“Did you ever find out who he was?”

“No,” Charlie admitted. “I never did.”

“Have you ever tried to?”

Charlie shook his head. “Honestly? I was told not to. But… maybe it’s time.”

That night, back in his hotel room, he lay awake staring at the ceiling. The war was half a century gone, but for the first time he realized he didn’t want to die without knowing. Without saying thank you.

He turned on the lamp, sat at the desk, and began writing a letter.

He started with official channels—old habits died hard.

He wrote to the U.S. Air Force Historical Office, explaining the date and mission details. He contacted the West German Air Force, now part of NATO, requesting access to Luftwaffe records from December 1943.

The replies came slowly, if at all. Some were polite rejections; others said records were incomplete or destroyed. One archivist wrote, “Sir, even if records survived, identifying one pilot from one day is near impossible.”

Charlie didn’t care. He’d faced worse odds.

He combed through his own logs and crew notes. He studied maps, trying to recall the exact route they’d flown, the point where the German had appeared. Bremen. The North Sea. Somewhere near Wilhelmshaven, maybe.

Weeks became months. Letters piled up on his desk—each one a dead end.

His daughter worried. “Dad, you’re obsessing.”

“I just need to know,” he said quietly. “He risked everything for us. The least I can do is find his name.”

He joined veteran newsletters and associations, sending out inquiries to any contact who might have known Luftwaffe pilots. Most wrote back with sympathy but no leads.

Still, he persisted.

Every night, he’d sit by the phone, a cup of coffee cooling beside him, scanning through documents by lamplight. He was sixty-four, his eyesight failing, but determination burned in him like it had in that cockpit all those years ago.

Three years passed. Nothing.

And then, one morning in late 1989, he tried a new approach.

He wrote a detailed account of the encounter and mailed it to the Combat Pilots Association Newsletter—a publication read by both American and German veterans. He described everything: the date, location, the bomber’s condition, even the enemy plane’s markings. And at the end, one simple line:

“If you were that pilot—or if you know who he was—please contact me. I owe him my life.”

He mailed the letter, said a silent prayer, and waited.

Thousands of miles away, in Vancouver, Canada, an old man named Franz Stigler was also waiting.

He had been a Luftwaffe ace during the war—a decorated fighter pilot with more than two dozen kills. But after December 20th, 1943, something in him had changed. He’d landed his Messerschmitt that day near Bremen and told no one what he’d done. If the Nazis had discovered he’d spared an enemy bomber, it would have meant execution.

He carried that secret his whole life.

In 1953, he’d immigrated to Canada, married a woman named Agnes, and built a quiet life as a businessman. He went hunting in the Rockies, fished in mountain streams, told no war stories. But sometimes, when the wind howled through the trees, he thought of that B-17. The shattered fuselage. The faces inside.

He never knew if they’d made it home.

He wondered for decades.

In January 1990, Franz was flipping through his copy of the Combat Pilots newsletter when a headline caught his eye.

“B-17 Pilot Seeks German Who Spared Him, Bremen 1943.”

His heart stopped.

He read the letter once, twice, three times. The details matched—everything matched. The date. The location. The description of the bomber’s condition. Even the salute.

His hands trembled as he reached for pen and paper.

“Dear Lt. Colonel Brown,

I was the one.

—Franz Stigler”

He mailed the letter to Miami, Florida.

On January 18, 1990, Charlie Brown found an envelope from Canada in his mailbox. The handwriting was neat, European. He opened it carefully.

Inside were four words that made his breath catch:

I was the one.

He sat down heavily at the kitchen table, reading the letter again and again. His hands shook. Tears filled his eyes.

Forty-seven years of silence ended with four words.

He called the number written at the bottom. A man answered in a gentle German accent.

“Mr. Stigler?” Charlie asked, his voice trembling.

“Yes,” Franz replied. “Are you… Charlie Brown?”

“Yes, I am.”

There was a pause, heavy with emotion. Then Franz said softly, “It is good to finally hear your voice.”

They talked for hours.

Franz described his aircraft in detail—the Messerschmitt Bf 109G, its yellow nose, the emblem on the tail. He recounted how he’d pulled alongside the bomber, seen the crew’s condition, and remembered his commanding officer’s words: ‘If I ever see you shoot at a man in a parachute, I’ll shoot you myself.’

He told Charlie, “To me, your bomber was like a man in a parachute. Helpless. I could not shoot.”

Charlie listened, tears streaming down his cheeks.

“I thought about you every day,” he whispered.

“I too,” Franz said quietly. “Every day.”

When the call ended, Charlie sat for a long time in silence, staring at the phone.

For the first time in forty-seven years, the nightmares eased. The question that had haunted him finally had an answer—and that answer had a name, a voice, a heart.

He looked out at the Miami sunset and whispered, “Thank you.”

Part III

The letter had been brief, but the call that followed changed both their lives.

After that first conversation in January 1990, Charlie and Franz spoke almost every week.

They talked about everything—the war, their families, their faith, the strange path that had led them back to each other nearly half a century later.

For the first time, both men could speak about that day freely.

No officers.

No propaganda.

Just two old pilots revisiting the single moment that had defined them.

Franz had been twenty-seven in December 1943, a Luftwaffe ace flying out of a base near Bremen. By then, the war had changed. Germany was losing. Pilots were exhausted, cities in ruins. Every sortie felt like a suicide mission.

He’d already lost his brother August, shot down over the North Sea in 1940. The grief hardened him. He kept flying, because it was all he knew.

But the day he saw the B-17 changed him.

“I remember it exactly,” he told Charlie during one of their early calls. “You came out of the clouds like a ghost. I saw holes everywhere—your tail almost gone, one engine burning, the nose shattered. I flew beside you, and I saw your men. Some were bleeding, some not moving. You looked… finished.”

He paused, his voice soft with memory. “I thought of my brother. Of all the men I had seen die. I thought, what honor is there in shooting this? This was not war anymore. It would have been murder.”

He explained that he had tried to signal Charlie to land in Germany, where the crew might get medical attention. But when Charlie refused and turned west, Franz made his decision. He’d fly beside them long enough to keep German flak gunners from firing.

“If anyone had seen me,” he said, “they would have called me a traitor.”

Charlie remembered his words from that night so vividly that it chilled him. “Your commanding officer—you mentioned something about parachutes?”

Franz chuckled softly. “Ja. Gustav Rödel. He told me once: ‘If I ever see or hear you shoot at a man in a parachute, I will shoot you myself.’ I never forgot that. To him, there was a line between honor and cruelty. And to me, you were just like those men in parachutes. You were helpless.”

The more they spoke, the more parallels they found in each other’s lives. Both had left the war behind to start over. Both had built new families, chased quiet peace after chaos. Both had been haunted by the same memory—one wondering if he’d spared lives, the other wondering if he’d been spared by chance.

By March 1990, Charlie said, “We’ve got to meet, Franz. After all this time—I want to shake your hand.”

Franz laughed. “I think we can do better than that.”

The First Meeting

They agreed to meet that summer in Seattle, at a veterans’ gathering hosted by Boeing. Cameras would be there. The company wanted to capture their reunion on film—a story of enemies turned brothers. Charlie didn’t care about cameras; he just wanted to see the man who had haunted his dreams for forty-seven years.

The day they met, the Seattle sky was pale and drizzling. Reporters stood back as a black sedan pulled up outside the hotel.

Charlie stood on the sidewalk, nervous as a cadet again, his dress coat buttoned tight against the chill. He’d lost weight over the years, his posture bent, but his eyes still carried that steady calm of a man who’d spent a lifetime looking up at the sky.

The car door opened.

A tall man stepped out—broad-shouldered despite his age, with a silver mustache and the straight-backed bearing of a soldier who never forgot parade ground discipline. Franz’s face broke into a smile as soon as he saw him.

“Charlie!” he called.

Charlie’s throat tightened. He didn’t move for a second. Then the years fell away, and he went forward fast, his arms open. Franz met him halfway. They embraced like brothers, clapping each other’s backs, both laughing and crying all at once.

For the crowd watching, it was a moment out of time—two men who should have killed each other, instead locked in a hug that defied history.

Franz turned to the cameras, his eyes wet, and said softly in his German-accented English, “I love you, Charlie.”

Charlie’s voice trembled when he answered. “I love you too, Franz.”

They sat together for hours, drinking coffee and talking as if the decades apart had been days. They compared details of that fateful mission—the weather, the altitude, the positions of their aircraft. Everything matched.

Charlie told him about Ye Olde Pub’s landing at RAF Seething, how the ground crews had stared in disbelief at the shredded bomber that somehow stayed in the air. Franz described how he’d landed back at his airfield and said nothing to anyone, afraid the SS would find out.

“You would have been executed?” Charlie asked.

Franz nodded. “Yes. Without question. To spare the enemy was betrayal.”

Charlie shook his head slowly. “You risked your life for us.”

Franz smiled faintly. “You were not my enemy that day. You were a fellow pilot, doing his duty. That was enough.”

When they parted that first evening, they hugged again, promising to stay in touch. Neither could stop smiling.

Charlie told reporters, “It’s like finding a brother you never knew you had.”

A few months later, Charlie arranged something even more special. He invited Franz to meet the surviving crew of Ye Olde Pub.

They gathered in a hangar in Florida, where a restored B-17 stood gleaming under fluorescent lights. The veterans, gray-haired and stooped now, lined up as Franz entered. There was a beat of silence, then one by one, the men stepped forward and shook his hand.

“Sir,” said one, voice thick with emotion, “if not for you, my kids wouldn’t be here.”

Franz swallowed hard, unable to speak.

Charlie’s daughter, Susan, brought her children—wide-eyed teenagers—to meet the man who’d saved their grandfather. They handed him a small framed photo: Ye Olde Pub crew, 1943, smiling in front of the bomber before the Bremen mission.

Franz stared at it for a long time, his eyes glistening. “So young,” he murmured. “So full of life.”

That evening, they all had dinner together. Laughter filled the room. The air buzzed with stories of the war—some grim, some absurdly funny. By the end of the night, Franz stood, lifted his glass, and said quietly, “To all the men who didn’t come home. And to those who did—may we never forget what mercy costs.”

Over the next few years, Charlie and Franz became inseparable. They phoned each other weekly, sometimes daily. They met at air shows, veteran gatherings, and museums. They gave joint talks about their story—not as propaganda, but as a living testament to humanity.

Wherever they went, audiences wept.

Charlie’s nightmares faded. He slept peacefully for the first time in forty-seven years. He told friends that hearing Franz’s voice had “quieted something deep inside me that had never stopped screaming.”

Franz found his own peace, too. He’d lived with guilt for decades—not for sparing lives, but for surviving when so many of his countrymen didn’t. He’d lost his brother, his friends, his home. But now, in Charlie, he found something that made it all bearable.

During one visit, Franz handed Charlie a small leather-bound book—his Luftwaffe flight log. Inside the cover, he had written:

“In 1940, I lost my only brother as a night fighter.

Thanks, Charlie. Your brother, Franz.”

Charlie couldn’t speak. He just closed the book and hugged him tight.

Not everyone celebrated their friendship.

Franz received letters from former German comrades who called him a traitor for sparing American lives. Some Canadian neighbors shunned him when they learned he’d been a German pilot. Others accused him of whitewashing history.

His response was always calm.

“They would never understand,” he told Charlie once. “They weren’t there. They never saw what I saw that day.”

Charlie had his critics too—men who said he was glorifying the enemy. But he didn’t care. “If a man risks his life to show mercy, that’s not the enemy,” he said. “That’s the best of what we can be.”

They both came to realize that their story wasn’t really about war. It was about what survives after war—the stubborn spark of decency that refuses to die even when surrounded by darkness.

Their families grew close. Charlie’s children called Franz “Uncle Franz,” and his wife Agnes became like an aunt to them. Holidays, birthdays, and family gatherings often included both men, sitting side by side at the table, trading jokes in their distinct accents.

In their twilight years, they’d meet in person whenever possible—Miami, Vancouver, Seattle, even small-town airfields. Franz would grin every time he saw a B-17 on display. “My old friend,” he’d say. “I almost shot you once.”

Charlie would laugh. “And I almost died of heart failure when I saw you coming.”

Once, while visiting an air museum, a young boy approached them shyly and asked, “Were you really enemies?”

Franz smiled down at him. “For ten minutes,” he said. “And brothers ever since.”

In interviews, both men often struggled to explain what had bound them together so completely. Charlie once told a journalist, “I think Franz and I were meant to meet. The war just got in the way for a while.”

Franz phrased it differently: “In war, we are told to hate. But hate is easy. Mercy—that is the hard thing.”

As the years rolled by, their story spread far beyond veteran circles. Newspapers, documentaries, even school textbooks began mentioning the encounter between the two pilots. They became symbols—not of combat, but of compassion.

When asked if he considered Franz a hero, Charlie smiled. “He was more than that. He was proof that you could still be human, even when the world told you not to be.”

In the mid-2000s, both men slowed down. Franz’s eyesight was failing; Charlie had heart problems. But they still talked on the phone every week, their voices warm with friendship.

When one would end a call, he’d always say, “I love you, brother.”

And the other would reply, “I love you too.”

The bond was unbreakable. They’d started as enemies, crossed half a century of silence, and found family where war once demanded hatred.

In 2008, at age ninety-two, Franz Stigler passed away in Vancouver, surrounded by family. When Charlie received the news, he wept quietly, holding the old leather flight logbook in his hands.

Eight months later, on November 24, 2008, Charlie Brown followed him.

They were buried thousands of miles apart—Franz in Canada, Charlie in Florida—but those who knew them said it didn’t matter. Their story had already tied them together forever.

After their deaths, their families helped complete a book about their story, titled A Higher Call. It became a bestseller, read by millions. But those who had known the two men said the real legacy wasn’t in print—it lived in how they had lived the last years of their lives.

Charlie’s daughter said at his funeral, “My father carried a question for forty years. When he finally found the answer, he found peace. Franz didn’t just save his life in 1943. He saved it again in 1990.”

At Franz’s service, a Canadian veteran stood and read a passage from his memoirs:

“Compassion does not recognize uniforms. In that moment over Bremen, a man remembered his soul. That was Franz.”

History is full of battles, but few moments remind us what it means to remain human within them.

For ten minutes in 1943, two men looked across a gulf of war and saw each other not as enemies, but as men.

Forty-seven years later, they met again—not as soldiers, but as brothers.

For the next eighteen years, they shared what the world had almost stolen from them: peace.

And in the end, they left behind a story that outlived both of them—a testament that even in the darkest skies, mercy can still fly.

THE END

News

CH2 – Nobody From My FAMILY Came To HOSPITAL “Not Even My HUSBAND” Nor My Closest — Then Nurse…

Part 1 The fluorescent lights above hummed in an even rhythm, a sound so constant that after a while, I…

CH2 – I Heard My Fiancé Tell Friends: “It’s Just Business. Her Money, My Looks.” I Texted: “Your Mic’s On.”

Part One: My name is Bonnie Tony, and until a few months ago, I thought my life was exactly where…

CH2 – HOA Banged on My Door at 6AM—My Day Off I Fired Warning Shots. They Sued I Won Big…

Part One At 6:04 in the morning, my doorbell camera caught a cardigan silhouette whacking my door with a clipboard…

CH2 – WHEN I LEFT THE ORPHANAGE AT EIGHTEEN, MY TEACHER ADVISED ME TO GO TO THE NOTARY FIRST AND FIND OUT…

Part One The notary didn’t even look up when he said it. “No one left you anything.” The words fell…

CH2 – I Warned the HOA About the Landslide—They Drove In Then Ran for Their Lives…

Part One At 3:11 in the afternoon, the cul-de-sac WhatsApp chat lit up like a Christmas tree on fire. Someone…

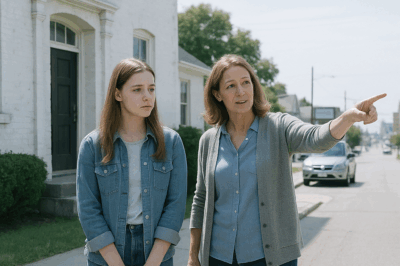

CH2 – Judge Did Not Believe My Wife Abused Me Until I Collapsed From A Heart Attack While Testifying…

Part One: If you’d met us seven years ago, you’d have said we were perfect. That’s what everyone said. “Clare…

End of content

No more pages to load