An American with red hair and kind hands saved my life today so I could meet my daughter tomorrow.

Greta Klene could have written the line from memory by now. She didn’t have to look at the page. But she did anyway.

The ink had faded to a tired brown. The notebook paper had gone the color of old tea, edges soft and frayed. But the words themselves—those careful letters, each one formed by a nineteen-year-old boy learning to write with his left hand—were as sharp as the day they dried.

She sat at her kitchen table in Berlin, autumn rain ticking against the windows, and traced the sentence with her fingertip like it was Braille.

Her father’s hand.

Her father’s voice.

On the hospice bed in 1998, his grip had been weak, papery skin stretched over bones, but his eyes had been as steady as they’d ever been.

“Find him,” he had said. “Tell him thank you. Promise me, Greta. Do not let me die without knowing someone will tell him what his choice meant.”

She had promised.

He had closed his eyes still holding her hand, still holding that promise between them like something sacred.

And now, fifty years later, a new line glowed on her laptop screen beside the old words on the page.

I think I found him.

She hadn’t clicked the attachment yet. Her heart didn’t seem capable of it. It pounded against her ribs as if it too were trying to back away from the mouse, from the photograph, from the possibility that everything she’d been chasing half her life was suddenly, impossibly, real.

The email was from a name she hadn’t seen before.

Marcus Chen.

A history student in Boston, he’d written. Working on a thesis about American medics in the last weeks of the war in Europe. Digitizing transcripts from nursing homes in Massachusetts. Cross-referencing them with unit rosters, division histories, battlefield reports.

The sort of thing people with computers and time did now.

The sort of thing her father had never lived to see.

Greta swallowed, wiped her palms on her jeans, and clicked.

The photo bloomed onto the screen.

A young man stared back at her from seventy years ago.

U.S. Army uniform. Dust and mud smeared across the wool. A medic’s armband stark white against his sleeve, the red cross dark in the black-and-white image. His helmet sat low on his head, chinstrap loose. His smile was big, almost too big for his narrow face, as if he hadn’t quite learned how to tame it yet.

Red hair, even in grayscale. She saw it anyway. The shade announced itself in the way it caught the light, the way it made the freckles scattered across his nose and cheeks look like constellations.

He was maybe twenty-two, twenty-three. Barely older than her father had been.

Beneath that, another photograph. Color this time.

The same man, decades later, the red turned to white. Face mapped with deep lines, the corners of his mouth dragged down by gravity and years. But the eyes—the eyes were the same.

Kind, tired, curious. Blue like late summer sky seen through smoke.

James Mitchell, the caption read. Corporal, 90th Infantry Division, Charlie Company.

Below the pictures, the rest of Marcus’s message:

I interviewed him last week for my thesis. When I mentioned wounded Germans near Weissenberg in late April 1945, he got very quiet. Then he said, “We saved so many boys that week. American boys, German boys—it did not matter anymore. We just wanted them to live. I hope they made it home. I hope they had families.”

Mrs. Klene, I think this is your man.

He lives at Sunrise Senior Care, Springfield, Massachusetts.

Address, phone, visiting hours attached.

I hope I’m right.

Greta yanked her gaze away from the screen, back to the diary. The open pages looked suddenly very small.

An American with red hair and kind hands…

Her father’s words, written in fading ink, sat beside the stark proof of pixels and color.

“I don’t know his name,” the entry continued, the lines following the famous sentence less often quoted, but now more important than ever. “I don’t know where he is from. I don’t know if he has a family waiting for him, if he will survive this war, but I know he is why I am alive. He is why tomorrow exists.”

Her finger trembled over the last part.

If I have a daughter someday, I will name her Greta, after my grandmother who taught me that kindness is stronger than hate. And I will tell her about this day, about the American who proved that enemies are just people who have not met yet.

He’d written that on April 27th, 1945.

Sixteen months before she was born.

A nineteen-year-old kid in a prisoner-of-war camp, his right hand mangled, teaching himself to write with his left because he had to get it down, had to capture what had happened before the details slipped away into pain and morphine haze.

In that muddy field he hadn’t known if he’d ever see Hamburg again, let alone have a daughter or grandchildren. He had only known that today existed when it wasn’t supposed to.

Greta pressed the heel of her hand against her eyes until stars burst behind her lids.

What if it’s not him?

What if she got on a plane, flew across the Atlantic, walked into that nursing home, and found some other James Mitchell, some other red-haired corporal who’d saved some other German boy in some other field?

The 90th Infantry Division had been thousands strong. There had been plenty of redheads in America in 1945.

And what if it was him… but it was gone?

What if you survived artillery, frostbite, the weight of all the broken bodies you’d tried to patch up, you made it to ninety, and your memories finally scattered? What if she stood at his bedside with her hands shaking and her father’s diary wide open and watched him frown at her with polite confusion?

What if, after half a century of searching and hoping and promising, she got her answer and it was: I don’t remember?

It would almost be easier if the email were a mistake.

Almost.

The rain streaked down the window, blurring the Berlin street beyond. Fifty years of dead ends came back to her in a rush.

The letters sent in clumsy English to official addresses that bounced back with “insufficient information.” The hours spent in archives in Hamburg, Bonn, Washington, wherever she could cajole her way into a reading room. The faded rosters, roll calls, casualty lists.

The veteran reunions where she stood at the edge of circles of American men in baseball caps, listening to stories told in a language she had only half mastered, stepping forward when someone mentioned “medic” or “Weissenberg” or “Weissen…something.”

So many Jameses. So many Jims and Jimmies and red-haired farm boys who’d come home and become mechanics, mailmen, electricians, teachers.

Opa’s American, her children had called him when they were small. The ghost grandfather they were helping their mother look for in the early days of the internet, squinting together at message boards and grainy scanned photographs.

Her husband had never once told her it was pointless. He’d booked train tickets and babysitters. He’d held her when she came back from yet another veteran’s reunion with polite smiles and wrong faces.

Now, a stranger in Boston had sent her two photographs, an address, and a handful of words.

I think I found him.

Greta reached for her phone.

Her fingers typed the airline’s app password without needing to look. Frankfurt to Boston. Morning flight. One seat.

She entered her credit card information like she was in a trance. When the confirmation email pinged into her inbox, it felt more real than anything had in years.

Before shutting the laptop, she leaned over the diary and read the last sentence on the page out loud, the way you read scripture at a bedside.

“If I have a daughter someday, I will name her Greta…”

“I’m coming, Papa,” she murmured. “We’re going.”

She wrapped the diary in a square of silk the same deep blue as her grandmother’s apron had been, tied the cloth carefully, and laid the bundle in her carry-on bag.

Whatever happened in Massachusetts, he was coming with her.

This journey was as much his as hers.

The jet’s engines droned a thick white noise that wrapped around Greta like cotton. An overnight flight was always a disorienting experience, even when you weren’t crossing sixty years of history at the same time.

The cabin lights were dimmed. A few screens glowed above blankets. Someone a few rows back was snoring softly. The air smelled like coffee, reheated pasta, and the faint chemical tang of pressurization.

Greta sat with the diary on her lap, the silk wrap folded back. The overhead light made the pages glow.

On April 26th, 1945, Hans Klene’s life had split into “before” and “after.”

She imagined him there in Hamburg in 1926, a baby in her grandmother’s arms, years before the swastikas and slogans and marching boots. Her father had given her the cliff notes of his childhood so many times she could see them now as clearly as if she’d been there.

The jazz records that lived in a crate beside the radio, the way his father’s eyes lit up when Louis Armstrong’s trumpet came through the static. The green-grocer on the corner, Mr. Goldstein, who slipped an apple into Hans’s hand when his mother wasn’t looking.

Teachers assigning books whose titles would later appear on lists of “degenerate” authors.

Then the bonfires.

The posters.

The way Mr. Goldstein’s shop stayed shuttered one morning and never opened again.

He’d been old enough at ten to see the before, young enough at fourteen to be folded into Hitlerjugend meetings and drills and indoctrination. Old enough at seventeen to be handed a uniform and a rifle and told that the Americans were monsters.

That part of his story had always made her stomach twist.

The instructors with their charts and photographs and the map of the United States, a pointer jabbing at neighborhoods: “This is not a nation,” the veteran with the limp had told them. “This is a zoo.”

Americans were mongrels, they’d said. A mixed-up, weak race, a circus of gangs and jazz and chaos. Too soft, too divided to fight. They’d tear each other apart long before they could defeat Germany.

It had probably been comforting to believe that, to imagine the enemy as something less than you, something inferior, stupid, cruel. It made the fear smaller. It made the ration cards and the bombings and the letters edged in black worth it.

Never mind that the boy saying “He is so young” in a roadside ditch in 1945 had been looking at someone almost exactly his own age.

The captain’s voice crackled over the intercom in English and German, announcing their descent into Boston. Greta closed the diary, tucked it under her arm, and watched as the patchwork of city lights swam up through the clouds to meet them.

An ocean and half a century were shrinking under the plane’s nose.

She wasn’t sure which distance felt bigger.

Springfield, Massachusetts, smelled like leaves and wet concrete when the taxi pulled up in front of Sunrise Senior Care.

Greta paid the driver, hefted her bag, and stood there for a moment in the parking lot, the brick facade of the nursing home rising in front of her.

It looked like a hundred other facilities she’d seen over the years. Clean lines, big windows, small lawn. A flagpole out front. Benches where, in summer, residents would be wheeled out to feel the sun.

Everything about it was aggressively ordinary.

It made the knot in her chest tighten.

Inside, the air was warm, a little too fragrant with disinfectant and something sweet and generic. The reception desk was decorated with fake autumn leaves and a hand-lettered sign that said WELCOME FALL.

A television played quietly in the common room to the right, where three residents dozed and one woman in a floral blouse watched a game show with intense concentration.

The clerk at the desk—a woman in her thirties wearing a sunflower lanyard with an ID badge clipped to it—looked up and smiled automatically.

“Hi there. Can I help you?”

“Um,” Greta said, the English sticking for a moment in her throat. “Yes. I am here to see Mr. James Mitchell.”

“Family?”

Greta hesitated.

“No. Friend,” she said. There wasn’t a box for what she was.

“Okay, hon, just sign in, and I’ll let the floor nurse know you’re headed up.”

Greta scribbled her name in the visitor log. Seeing “Berlin, Germany” in the address line made her feel suddenly conspicuous.

She smoothed the silk-wrapped diary in her bag.

The elevator doors hummed open.

On the second floor, the hallway was lined with print reproductions of calm landscapes—lakes, trees, sunlit meadows. Somewhere, a radio played big band music low enough that she could only catch the occasional brassy swell.

A nurse pointed her toward the far end.

“He likes the window,” the woman said. “You flew in from Germany just to see him?”

“Yes.”

“That’s… something.” The nurse smiled, not unkindly. “He’s a good man.”

Greta’s breath caught.

You’ve never met him, she told herself. Not really. He could be cranky, dismissive, confused. He could look at you and see nothing. Don’t build him into a saint.

She walked down the hall anyway.

The door to his room was open.

He was there, in a wheelchair by the window, just like Marcus had said in his email. The garden beyond the glass was small, but somebody had taken care to make it pleasant: a maple dropping red leaves onto a path, a bird feeder swinging from a metal hook.

The man in the chair had a blanket over his lap, a sweater pulled tight around shoulders that seemed too narrow for his frame. His hair was white, thin. The skin along his jaw and neck sagged with the soft heaviness of age.

But the hands on the armrests were large and square, the knuckles knobby but strong.

Hands that had pressed against her father’s shoulder through wool and blood.

Hands that had steadied a pistol out of a boy’s grip and shoved it safely into the mud.

Greta stood in the doorway for a heartbeat, her fingers gripping the diary so tightly it hurt.

Then she stepped inside.

“Mr. Mitchell?”

He turned his head toward her voice. The motion was slow, but his eyes when they found her were clear and sharp, bright blue in a face creased by time.

“Yes?” he said. The voice had the soft rasp of the elderly, but there was strength in it yet.

“My name is Greta,” she said. “Greta Klene. I have… I have come from Germany to see you.”

He blinked.

“Germany,” he repeated, tasting the word like it was strange in his mouth.

“I know this must be unexpected, but I think…” She swallowed. “I think you saved my father’s life.”

For a second, nothing moved.

The air conditioner hummed. Voices drifted faintly from the hallway. Somewhere down the corridor a cart rattled by.

James Mitchell—Corporal, 90th Infantry, Charlie Company, retired high school teacher, widower, ninety years old—stared at her as if trying to see past her face, through layers of years and miles.

“I don’t understand,” he said, shaking his head slightly. “I mean, that’s… That’s a big thing to say.”

“In April 1945,” she said, the words coming faster now, the dam finally broken. “You were with the 90th Infantry Division, near a town called Weissenberg. You came upon a wounded German soldier in a roadside ditch. He was nineteen years old. His leg was shattered. He had a pistol pressed to his head. You…” Her voice wobbled. “You took the pistol away. You called for a medic. You saved him.”

Mitchell’s hands tightened on the armrests. The knuckles went white.

He looked down, then back up at her.

“There were a lot of wounded soldiers,” he said slowly. “We tried to help…all of them. Ours. Theirs. By then it didn’t much matter what color uniform they were wearin’. They were just boys bleeding in mud.”

“This one was named Hans,” Greta said. “Hans Klene. He was from Hamburg. He was my father.”

Something flickered across Mitchell’s face. Not recognition exactly, but an old, buried feeling stirred by the right combination of words.

“Your father…” he murmured.

She took a step closer, heart pounding, and unwrapped the diary.

“He wrote about you,” she said. “He kept this with him his whole life. He started writing in the field hospital, with his left hand, because his right was damaged. This is…this is the entry from the next day.”

She cleared her throat and read, her voice steady despite the tremor in her fingers.

“‘An American with red hair and kind hands saved my life today so I could meet my daughter tomorrow.’”

She looked up.

Mitchell’s eyes were wet.

“Red hair,” he said hoarsely, almost to himself. He reached one shaking hand up to touch his own scalp, as if remembering a version of it from a mirror long gone. “They used to call me ‘Red’ back then. I… I had hair like a matchstick.”

“I know,” Greta said, a laugh breaking through her tears. “I saw the picture.”

She held the photo out—the young medic in black and white, the grin, the freckles, the armband. Mitchell took it between thumb and forefinger, as though it might tear if he breathed on it.

“My God,” he whispered.

Greta sat down in the chair beside him.

“My father did not know your name,” she said. “He spent years trying to find out. He even got help from an American engineer after the war. But there were too many red-haired corporals. Too many medics. When he died, he made me promise I would keep looking.”

She took a breath.

“It has been fifty years, Mr. Mitchell. I… I think I found you.”

He was silent for a long time.

Outside, a bird landed on the feeder and flicked its wings, scattering seed.

When he finally spoke, his voice was thin but clear.

“Close the book for a minute,” he said.

She did.

He stared at the closed cover like he could see his own hands in there, working over fabric and bone.

“I was nineteen when I joined up,” he said. “Two years older than your daddy, I guess. From a little farm town in Pennsylvania nobody’s ever heard of. I didn’t know a damn thing about anything. Ivy League boys got officer school. Guys like me got bandages and morphine. Medic school.”

His mouth twisted in something like a smile.

“We hit France late. Got chewed up in hedgerows and mud. By the time we were pushing into Germany, I’d seen more insides of people than God ever intended.” He looked at her. “I remember… Weissenberg. I think I do. It was all running together by then, but I remember how quiet it got after that barrage. You know that kind of quiet where your ears ring and you start wonderin’ if it’s you or the world that quit making noise?”

Greta nodded. She’d heard that description from Hans, in almost the same words.

“There were bodies everywhere,” Mitchell went on. “Ours. Theirs. We were supposed to move, keep advancing, but the lieutenant…” He swallowed. “He had a conscience. Told us to check the ditches. ‘Anyone still breathing, you haul ’em out.’”

He closed his eyes.

“I saw a kid,” he said. “Skinny, scared. Left leg looked like it had been through a meat grinder. Blood all in the mud. He had a pistol to his head. I remember that part clear as day. Shaking so hard the barrel kept slipping. I thought, ‘Hell, he’s just a boy. Looks like my cousin Eddie.’”

His hand lifted, fingers curling around the memory of a rifle grip.

“I pointed the gun,” he said. “I could’ve… I mean, that’s what some guys did. End his pain. End the risk. But he looked up at me like a cornered deer. And I guess I just…couldn’t. So I told him something—God knows what, my German was awful—and I put my hand out. He let go of the pistol. I called Doc over. We splinted that leg as best we could. Gave him morphine. Sent him on a truck.”

He opened his eyes again.

“And that was it,” he said quietly. “I never knew his name. I never knew if he lived or died. Sometimes at night, in the worst of it, I’d see his face and a hundred like it, and I’d wonder. Did I help? Did it matter, or did he just die slower somewhere else?”

Greta swallowed around the lump in her throat.

“It mattered,” she said. “He lived. He kept the leg. He spent six months in a POW camp, came home to a ruined city, rebuilt it. He married. He had two children. My brother, Martin, and me. He had five grandchildren. He…he laughed a lot. He worked hard. He brought my grandmother flowers on their anniversary. He could be stubborn and proud and annoying. But he was here, Mr. Mitchell. Because of you.”

She opened the diary again, turning to the page her father had shown her when she was twelve, his finger tracing the words like a blessing.

“He wanted me to tell you something,” she said. “He said, ‘Tell him that every good thing in my life, every sunrise I saw, every meal I shared, every time I held my children, I owed to him. Tell him he did not just save one life. He saved all the lives that came after.’”

Mitchell’s shoulders shook.

She realized with a start that the old man was crying.

“I always felt guilty,” he said thickly, tears sliding into the wrinkles at the corners of his mouth. “You know that? I’d close my eyes and see the ones we couldn’t get to. Too far gone. Too late. I’d wonder if God kept a ledger, tallyin’ up the ones I failed. It… It does something to you, seeing that much hurt. I tried to make up for it, teaching after the war, trying to get kids to talk instead of fight. But I never knew if any of it…” He broke off, shook his head. “I never knew any of it stuck.”

“It stuck with my father,” Greta said softly. “Every year on April 26th, he told us the story. He called it his personal holiday. The day an American gave him back his life. He taught us English because of you. He made us learn it, he said, so we would never again see the world through only one language. He…he wouldn’t let us make jokes about ‘the Americans’ or ‘the British’ or ‘the Russians’ as if they were all the same. ‘Enemies are just people who have not met yet,’ he would say. ‘I met one in a ditch. He had red hair and kind hands.’”

Mitchell laughed through his tears, an incredulous, broken sound.

“That sounds like a man I’d have liked to know,” he said.

“You did,” Greta said. “For ninety seconds.”

She reached out without thinking and took his hand.

His skin was warm, paper-thin. The bones beneath felt fragile but stubborn.

She had imagined these hands for so long. It felt impossible that they were real and solid under her fingers.

“Thank you,” she said. “For giving me my father. For giving me my life. For giving my children their grandfather.”

Mitchell squeezed, weakly but with intent.

“Thank you,” he said. “For finding me. For letting me know it mattered. For letting me know he lived.”

They sat there for hours.

The nurse peeked in once, saw the two of them leaning toward each other, talking softly, and backed away without interrupting.

Greta told him about the rest: the field hospital in the converted barn, where Hans had shared a row of cots with American boys his own age. The older German soldier who’d asked if they were in heaven because he couldn’t understand being tended by the enemy.

The American doctor who’d come around with halting German, pronouncing Hans “lucky” to keep his leg.

“The POW camp wasn’t… what he expected,” she said. “He thought he would be tortured. Starved. But it was mostly boredom. Paperwork. Too much time to think. One of the American guards brought him engineering manuals when he found out what my father had studied. He said Germany would need men who could rebuild, not just destroy.”

Mitchell nodded slowly.

“Sounds like Sergeant Meyers,” he said. “He was always sneakin’ the Kraut kids books when we pulled guard. Got chewed out for it more than once.”

Greta smiled.

“He came home in 1945 to a city in ruins,” she said. “His father had been killed in a bombing. His mother and sister were living in a cellar. He helped rebuild Hamburg. He always said his leg hurt when it rained, but he never complained much. Only when the soccer games on Sunday went too long.”

She told him about Margaret, the girl who’d written letters during the war and waited afterward. About the small apartment where they’d raised their children. About Hans’s quiet friendships with American engineers during the occupation years.

“He tried to find you,” she said. “He had your hair color, your likely rank, your unit, the date. He and a Lieutenant Thompson wrote letters, but the answers…there were too many possibilities. Too many J. Mitchells. After a while he started to think maybe you’d died in some other field, some other war. But he never stopped telling the story.”

She told him about Hans at the kitchen table with a dictionary, making her repeat English words after him. About the night he’d finally shared the diary, letting her thumb the fragile pages with both awe and the clumsiness of a twelve-year-old.

“He said, ‘When you are older, when technology makes the world smaller, find him,’” Greta said. “‘Tell him thank you. Tell him his mercy was not wasted.’”

Mitchell listened with a stillness that seemed to fill the room. Every so often he’d close his eyes, and she wondered if he was matching her words with his own memories, laying them side by side like transparencies until they aligned.

When she asked about his life, his story came in fits and starts.

He’d come home in 1945 to a parade he’d wanted no part of. He’d gone to school on the GI Bill, thinking maybe he’d be a doctor, but his hands shook when he saw too much blood. Eventually he’d turned to teaching instead.

“High school history,” he said. “Figured if I could keep a bunch of seventeen-year-olds from killing each other, I’d be doing all right.”

He talked about the nightmares. The faces that had followed him into his thirties, forties, fifties. The way he’d avoided war movies, fireworks, even the sound of a car backfiring for a long time.

“I tried to get them to see each other as people,” he said. “The kids. Black kids, white kids, rich, poor. I’d tell ’em stories about the war, but not the ones with flags and glory. The ones with scared boys on both sides. Sometimes I thought I was just ramblin’ and they weren’t listening. Then one would come back ten years later and say, ‘Mr. Mitchell, I remembered what you said, and I didn’t swing that punch,’ and I’d think maybe—just maybe—it was worth it.”

“It was,” Greta said.

Before she left that afternoon, she asked if she could take a photograph.

Mitchell straightened a little in his chair, smoothing his sweater.

She placed the diary in his hands, open to the famous line, and stepped back. The late-day sun slanted through the window, turning his white hair into a halo.

“Ready?” she asked.

He nodded.

She clicked the shutter.

In the photo, when she looked at it later on the train back to Boston, his eyes shone behind wet lashes, his mouth curved in a tentative, wonder-struck smile.

She emailed a copy to Marcus that night with a long message of thanks.

You were right, she wrote. It was him.

Eighteen months later, Greta stood under an American sky again.

The cemetery was green and well kept, the grass clipped close. Headstones lined up in even rows, some old and darkened, some bright and new. There were flags on some, plastic flowers on others.

The Mitchell family had gathered in a loose cluster by the open grave. Children in dark jackets fidgeted beside parents. An elderly woman dabbed at her eyes with a tissue. A younger man who looked very much like James in the 1945 photo—same narrow face, same set of the jaw—stood with his arm around a woman in a navy dress.

The pastor’s words washed over Greta in English that she understood more with her heart than with her head.

“…a good and faithful servant…”

“…husband, father, teacher, friend…”

“…served his country…served his community…”

She held the diary in her hands like a talisman.

When the pastor finished and stepped back, the family’s eyes turned toward her.

James’s son—David—had asked her before the service if she would speak.

“You knew a part of him we didn’t,” he’d said, voice thick. “I think he’d like that.”

She hadn’t known how to explain that she’d only met the man twice in person and a hundred times in her father’s stories. That she knew nineteen-year-old “Red” from the inside out, but ninety-year-old Mr. Mitchell remained a brief, precious glimpse.

Now she stepped forward anyway.

“Thank you,” she said, nodding to the pastor, then to the family. She cleared her throat, and when she spoke again, her German accent was more obvious than usual. She didn’t try to hide it.

“My name is Greta,” she said. “I came from Germany to be here today. My father could not be here because he passed away some years ago. But in a way, he is very much here.”

She held up the diary.

“In April 1945, my father, Hans, was a nineteen-year-old German soldier lying in a ditch, bleeding into the mud. His leg was shattered. He had a pistol pressed to his head because he had been told all his life that Americans would torture him if he surrendered. That they were monsters. That he would be better off dead.”

She let the murmurs settle.

“An American soldier found him. He was also very young. Red hair. Freckles. Tired eyes. He could have walked past. He could have shot my father and not one of his officers would have questioned it. Instead, he took the pistol away. He put a hand on my father’s shoulder. He called for a medic. He stayed with him while my father screamed and bled and nearly passed out from pain. He chose mercy when the world was telling him to hate.”

She opened the diary to the marked page.

“The next day, in a field hospital, my father wrote: ‘An American with red hair and kind hands saved my life today so I could meet my daughter tomorrow.’”

A breeze stirred the pages. A few leaves skittered across the grass in front of the grave.

“My father did have that daughter,” she said, smiling through the sting in her eyes. “Me. He had a son. He had five grandchildren. He rebuilt houses and bridges instead of destroying them. He laughed, he loved, he grew old. Every year on April twenty-sixth he told us the story of the American who had given him his life back.”

She looked down at the coffin, then at the faces around it.

“When my father died, he made me promise to find that American. It took fifty years. Many wrong turns. Many ‘James Mitchells’ who were not this one. But with the help of a young historian and a very patient God, I finally walked into a nursing home in Springfield, Massachusetts, and met the man whose hands had been on my father’s shoulder in that ditch.”

She let herself look at David Mitchell then, at the way his jaw clenched.

“I told your father what his choice had done,” she said. “I told him about Hamburg, about my mother, about birthdays and Christmases and grandchildren. I told him that every good thing in my father’s life, every sunrise, every meal, every time he held us, was because of him. That he had not just saved one life, but all the lives that came after.”

Her voice steadied.

“He said he had always hoped the boys he saved made it home. That they had families. That they lived. I was able to look into his eyes and say, ‘Yes. He lived. And he was happy.’”

She closed the diary gently.

“At the end of his life, your father wondered, I think, if what he did in those terrible days had mattered,” she said. “I am here to tell you it did. It matters—right now, in this moment. I am here because of him. My children exist because of him. Somewhere in Germany, there are six energetic, loud, wonderful great-grandchildren of Hans and Margaret who owe their entire existence to an American farm boy who decided, in a field far from home, that a stranger’s life was worth saving.”

She took a breath.

“That is his legacy,” she said. “Not only as an American soldier, but as a human being. In humanity’s darkest hours, he chose kindness over cruelty. Mercy over vengeance. Hope over hate. That choice echoes forward through generations. I will tell my grandchildren about your father, just as my father told me. I will tell them that enemies are just people who have not met yet, and that one man with red hair and kind hands proved that with his actions.”

She looked up at the sky, at the white clouds drifting lazy across the blue.

“Danke,” she said softly. “Thank you, James.”

As she stepped back into the small crowd, David reached for her hand.

“Thank you,” he whispered, his voice breaking. “For giving us…that. For letting us see him the way you do.”

Greta squeezed back.

“Thank you,” she said, “for sharing him with us.”

Back in Berlin, on the next April 26th, Greta sat at her kitchen table with the diary open and a new photograph propped up against a mug of tea.

Her grandchildren—three of them, at least—clustered around her, sticky fingers on the edge of the table, eyes wide.

“Again, Oma,” little Lina said. “Tell it again.”

“You know this story by heart,” Greta protested.

“So do you,” Lina said seriously. “But you still read it.”

Greta laughed.

“Fair point.”

She smoothed the fragile pages and began.

“Once upon a time,” she said, “in a muddy field in a country far away, a nineteen-year-old boy named Hans thought he was going to die…”

She told them about the ditch, the shattered leg, the cold pistol barrel against hot skin. She told them about the red-haired American who bent down and said something Hans couldn’t understand, but whose tone he felt in his bones.

She read the line aloud, as she always did at the same point.

“‘An American with red hair and kind hands saved my life today so I could meet my daughter tomorrow.’”

“That’s you,” Lina said, even though she’d heard it a hundred times.

“That’s me,” Greta said. “And this is him.”

She picked up the photo of James Mitchell at ninety, holding the diary, eyes damp, mouth curved in that amazed, grateful smile.

“He was very old when I met him,” she said. “His hair was white instead of red. But his hands were still kind.”

“What happened after?” one of the boys asked, even though he knew the answer too. Children liked repetition. It was how they dug grooves in their memories.

“He died,” Greta said gently. “He was very tired. His family and I said goodbye. And then we told his story, like we are doing now.”

“Are you sad?” Lina asked.

“Yes,” Greta said. “And happy. Sad that he is gone. Happy that I got to find him. That I got to tell him thank you. That I got to close the circle.”

She looked down at the diary, at the neat left-handed script of a boy who’d been taught to hate and had chosen instead to be changed by kindness.

She thought of that muddy April morning, of boots in the mud and a voice saying something he didn’t understand but which meant: Don’t. Please don’t. You matter.

She thought of a farm boy from Pennsylvania who’d grown up, grown old, worried that the moments he’d chosen mercy might have been swallowed by the dark.

They hadn’t been.

They had made it across oceans and decades, across languages and broken cities and rebuilt lives, and come to rest here, in a Berlin kitchen where children with two countries in their blood leaned in to hear about how it had all almost ended before it began.

Greta closed the diary and laid her hand over the cover.

“Remember,” she told her grandchildren, “that every person you meet is someone’s child. Someone’s father. Someone’s future. Remember that you always have a choice, even when the world tells you otherwise.”

She glanced at the photo of James one more time.

“An American with red hair and kind hands saved my life today so I could meet my daughter tomorrow,” she read silently, letting the words settle.

Her father had been right.

Tomorrow did come.

And when it did, she found the man who had made it possible, took his hands in hers, and told him that his kindness had not been forgotten.

THE END

News

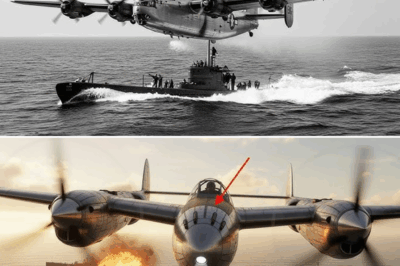

The Admiral Banished Her From the Carrier — Then a Nuclear Submarine Surfaced Against His Orders

The admiral didn’t raise his voice. That was what made it worse. “Commander Astria Hail,” Admiral Malcolm Witcraftoff said, each…

“YOU HAVE ONE MINUTE TO GET OUT,” HE SHOUTED. I SIMPLY SMILED AND SAID, “THANK YOU.” BUT SECONDS LATER,

He gave me one minute. “One minute to get out,” he shouted, voice booming against the glass walls of the…

CH2 – The Forgotten Plane That Hunted German Subs Into Extinction — The Wolves Became Sheep

The gray dawn broke over the North Atlantic like a bruise. Low clouds pressed down on a heaving slate sea….

CH2 – Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day…

May 18th, 1944. Biak Island, Dutch New Guinea. The air tasted like hot rust and rotting leaves. Every breath felt…

CH2 – “Sleep Without Your Clothes” the British Soldier Said – The Order That Terrified German Women POWs…

“Sleep without your clothes.” The words were plain, almost bored. But when the British private said them in clipped English…

CH2 – German Officers Smirked at American Rations, Until They Tasted the Army That Never Starved

December 17, 1944 Ardennes Forest, Belgium The ground didn’t crunch under Oberführer Klaus Dietrich’s boots so much as crack and…

End of content

No more pages to load