On a desolate stretch of road in northern Germany, in the wet, uncertain spring of 1945, a convoy of British lorries crawled through the mud like tired animals.

The war in Europe, people kept saying, was over.

But for the women in the back of the last truck, jostling against one another under a sagging canvas roof, it felt less like an ending and more like a strange, suspended fall. The bombs had stopped. The artillery had gone quiet. The uniforms outside were a different color now. And yet nothing inside their own bodies had changed.

They were still broken.

The rear of the lorry smelled of damp wool and blood that was starting to sour. Rain seeped in around the seams of the canvas and tapped softly on helmets and hair. Two dozen German women lay or half-sat on folded stretchers lashed crudely to the sides, or on rough benches that had not been designed for the paralyzed.

Most were young—barely out of girlhood—former communications aides, clerks, drivers. Auxiliary personnel who had drifted toward the front as the Reich dissolved, same way debris is sucked toward the center of a whirlpool just before it disappears.

They had shrapnel embedded in spines. Bullet wounds tunneling through backs. Vertebrae fractured by blast waves that had thrown them like dolls. Their injuries had been examined in the last weeks of the war only long enough for someone behind a clipboard to scrawl “Transport if possible” or “Not fit to move—leave.”

Then the front moved anyway.

Now, tossed about with each rut in the road, they carried with them:

Uncleaned wounds. The heavy, hollow realization that their legs did not answer when called. The ice-cold dread of a future they could not picture.

They said little.

They had been taught that silence was strength and that crying was for the weak. They had been taught many things.

Near the tailgate, propped against the wooden slats and trying not to show how much the jolts hurt, lay Aara.

Her dark hair clung to her forehead in damp curls. Mud and soot had fused with the last remnants of Berlin powder on her cheeks. She had been a signals operator in the capital—telephones, codes, endless hours in headphones connecting voices that barked orders she was not allowed to question.

That felt like another life now.

Aara’s lower body was a void. In the last raid near the Chancellery—one more shrieking descent of steel into a city already blown open—a building had folded inward. Something heavy had slammed across her back. There had been a bright flash of pain, and then…nothing. No sensation from the waist down. No movement. Just the smell of dust and her own fear.

She had climbed out of that rubble with her arms, dragging her dead legs behind her until other hands pulled her the rest of the way. She had done her duty, she thought bitterly. She had become one more piece of wreckage.

Now she lay in British custody. Her mind still worked with frantic precision, cataloging every sound of the engine, every attempt at translation from the girl near the front who knew a little English, every sideways glance from the other women.

Her expression stayed fixed in that tight, skeptical mask she’d perfected since childhood, eyes narrowed slightly, lips pressed together. It was her last shield: watch everything, trust nothing.

To Aara’s right, wedged between a crate of bandages and another wounded woman, sat Greta.

Greta’s hair had once been the color of summer straw. Now it looked washed-out in a way that had nothing to do with rain. She couldn’t have been more than twenty. Before the last months, she’d been an office clerk in a provincial town, stamping documents, filing forms, drinking weak coffee, watching trains from her second-story window and imagining…well, she was no longer sure what she’d imagined.

Near the end, when the front swallowed her town, the Party had “invited” her to help at a nearby logistics unit. “Just typing,” they’d said. A shell had landed during a night barrage as she was running between buildings with a crate of files in her arms. A single bullet from a burst of machine-gun fire had entered her back and exited just above her hip.

She remembered the impact more than the pain. Like being punched by God.

No sensation below the wound now. Doctors—those who still cared enough to glance at her—had used the word Querschnittslähmung in tired voices: paralysis. Complete.

Greta’s face was very pale. Her jaw clenched and unclenched almost imperceptibly, as if she were still trying to keep her teeth from chattering out of the shock.

Across from them lay Liisa.

Older than the others by a decade, maybe more. Her blonde hair had gone silver at the temples, twisted back under a torn scarf. Before everything, she had been a supervisor in a communications office, the kind of woman younger girls either feared or admired. The sort whose shoes clicked down corridors while others jumped out of the way.

Her injury had come from a collapsing stairwell and bad luck. A chunk of masonry had struck her high on the spine, snapping her head back so hard something inside gave way. She still had some movement in her arms, some sensation in her hands. But every attempt to turn her neck sent white-hot lightning through her entire body.

She had spoken maybe ten words since they loaded her onto the truck.

Not because she couldn’t.

Because silence was the last border she controlled.

None of the three reached out to touch the others. None sought comfort in shared misery. Culture, training, and raw pain built walls higher than language barriers.

Besides, what could you say?

“I hurt?” They all did.

“I’m afraid?” They all were.

So they endured. They listened to the canvas whistle in the wind. To the squelch of tires. To the dull thunk of their own expectations:

The British will be cruel. The British will use us. The British will show you in their faces all that you have lost.

That was what they had been told.

That was what they had believed.

The convoy finally slowed.

Brakes squealed. Gears ground reluctantly. The truck lurched once, twice, then shuddered to a stop.

Outside, boots hit the ground. Men’s voices, speaking English in those clipped, rhythmic patterns, moved along the line of vehicles. A barked order. A short laugh. No drunken shouting, no wildness—just the businesslike choreography of men who had been doing this for a long time.

The tailgate banged down.

Cold, gray light knifed into the dark interior as a gloved hand pulled the canvas flap aside. Aara squinted, then adjusted. The first thing she saw was a Sten gun, hanging on a strap across a khaki chest.

Then she saw the man carrying it.

British sergeant. Late twenties, maybe. Weathered face, jaw clenched around whatever he was holding back. Mud spattered on his boots, his webbing, his cap. His expression was careful; it might once have been warm, or hard, or both. Right now it was simply…professional.

He swept his gaze over the women. Aara braced for the curl of a lip, the flare of contempt.

His eyes were searching, not sneering.

He spoke in English, voice steady. Then he half-turned, and a young woman in a British uniform—cap perched askew over dark hair—translated into stiff but earnest German.

“Right, then, ladies,” the sergeant had said. “We’ve arrived. We’ll move you on stretchers now, one at a time. No need to hurry.”

“No need to hurry,” the interpreter repeated, the phrase sounding strange in their language. “We lift you one by one. Slowly.”

Aara’s breath hitched.

She had prepared herself for rough hands, for barks of “Up, up!” or “Move!” For the impersonal shove of victors dealing with broken enemies.

Instead, two British soldiers climbed into the lorry—muddy, tired, smelling of cigarettes and wet wool. One looked down at the clipboard in his hand, then at Aara.

His eyes flicked to her legs, then back to her face. Not in disgust. Just assessing.

“Let’s get you sorted,” he said quietly. The interpreter tried to keep up.

They slid a canvas stretcher under her with practiced care. As they lifted, Aara couldn’t suppress a wince. The muscles in her shoulders flared—her arms were the only part of her still doing more than their share of work these days.

One of the men felt her tense and adjusted his grip, shifting the angle so her upper back stayed straight.

“Easy now,” he murmured, English rounding his vowels.

The interpreter didn’t translate that. She didn’t need to. Tone traveled well enough.

No rebukes. No sighs of impatience at her involuntary groan. No jokes tossed over her head at “the cowardly Frauleins.”

It was almost worse than abuse.

She did not understand what to do with the absence of cruelty.

Greta’s turn came next. Her stretcher wobbled as they navigated a muddy rut near the tailgate, and she bit back a cry, hands gripping the sides until her knuckles turned white. One of the privates glanced down.

“Sorry, miss,” he said, carefully correcting, then, “Greta, ja? Nearly there.”

She watched his face, searching for mockery.

There was none.

Liisa, with her fragile neck, was moved last. The soldiers checked her brace twice, conferred in low voices with the nurse who’d been riding with them, and then lifted her like glass.

The building they were carried toward sat low and solid on the edge of what looked like a small camp. Wire fencing. Timber watchtowers. Armed men. From a distance, it might have been mistaken for a prison.

Up close, the smell gave it away.

Disinfectant. Boiled water. A hint of carbolic soap. Under it, the sharper tang of antiseptic.

Aara had been in German aid stations that reeked of blood and unwashed bodies, corridors filled with men moaning on stretchers while overworked orderlies stepped around them.

This place smelled like someone had attacked it with a scrub brush until they were satisfied.

Inside, the ceilings were low, the walls whitewashed so recently flecks still flaked away under the bump of a stretcher. Tables had been pushed aside to make room for lines of beds. A big clock ticked on one wall—pure, indifferent rhythm.

They were processed, but not like cattle.

Names, spoken in German, written in neat English letters. Former units. Location and date of injury. A brief pause from a clerk when Aara said “Berlin” and “Chancellery,” then only a nod.

“Medical next,” the interpreter told them.

Two British doctors waited at the far end of the ward.

One was tall and gaunt, sleeves rolled up over wiry forearms, stethoscope hanging around his neck. The other was shorter, his hair thinning prematurely, spectacles perched low on his nose as he read a chart. Both wore khaki shirts under white coats. Neither smiled. But neither wore the look of faint revulsion Aara had grown used to seeing from some German doctors when a case didn’t seem “worth it.”

“We are here to stabilize your condition,” the tall doctor said. His German was halting, so he nodded to the nurse to relay it more clearly. “Your wounds will be cleaned, dressed, and assessed for long-term care. We will prevent infection where we can. We will manage pain.”

He said it like a checklist, like a mechanic reciting the steps for a tune-up.

Clinical.

Not sympathetic.

But not cruel.

Liisa watched him approach with cold, narrowed eyes. She had not been offered treatment without strings since the war began, and even then it had often come with threats. You want bandages? You want morphine? Sign here. Work there. Tell us this.

Now, the doctor touched the edge of her brace with two fingers.

“When did you lose sensation in the legs?” he asked, through the nurse.

She hesitated.

“After…after the second blast,” she said finally, voice like gravel. “There was a…fall. Stairs.”

He palpated gently along her shoulders, then down her spine as far as she could tolerate. His hands were impersonal but careful. Every time she stiffened, he paused, letting the pain ebb before continuing.

“We will get you into a suitable traction brace,” he said, dictating an order. “The damage is severe, but we must prevent further injury.”

No lecture. No, Well, perhaps you should have stayed at home instead of doing a man’s job. Just an assessment, and a plan.

Greta flinched when it was her turn, but the shorter doctor had the kind of face people trusted without meaning to.

He examined the bullet wound on her back, the angry red track where metal had torn flesh on the way in and out. The skin around it was swollen, shiny with inflammation.

“These must be thoroughly cleaned,” he said, his mouth tightening. “Infection risk is very high.”

Greta stared up at him. Wounds that don’t kill you outright still kill you later, she thought numbly. That had been the rule these last months.

“We will keep you in this ward for continuous observation,” he added.

Her mind snagged on we. Not “you Germans.” Not “the enemy.” Just “we, the staff of this place, doing what we do because that is what we do.”

Aara’s exam was last.

She’d suspected the worst. She’d tried, when no one was looking, to dig fingernails into her thighs, to see if pain would flare.

Nothing.

The doctor’s hands were systematic. He tapped the knee with a rubber hammer. No reflex. He pricked the skin lightly with a pin. No flinch. He watched her eyes, not trusting her words alone.

“The spinal cord is impacted,” he said at last, voice lower, the way mechanics spoke when they knew a bearing had seized and there was no saving it. “Full mobility may not return.”

He saw her jaw tighten.

“We will provide mobility aids and physical therapy,” he went on. “The war is over. Your fight now is different.”

She lay still while he wrote.

Her mind, for once, was not racing ahead. It sat frozen over a single word: may.

May not.

Which meant—illogically, absurdly—may.

After the examinations, they were rolled into actual beds.

Not bedframes in corridors, not pallets on floors. Real beds. Clean sheets that scratched slightly, but in a friendly, familiar way. Wool blankets that smelled of soap instead of mildew.

Water came in cups. Food in bowls—a thin broth, yes, but hot. Soft bread. Even tea, weak and pale but hot enough to hold between cold hands and feel something like human again.

They ate.

Greta’s shoulders slumped with the first spoonful. The tension in her jaw, which had been welded tight against agony for weeks, eased by slow degrees. Liisa eyed the tray as if it might vanish, then lifted the cup, fingers awkward around the porcelain, and sipped.

Aara took tiny bites, her mind cataloging each new taste against memory:

This is not substitute coffee laced with barley husks. This is not scraped-bottom-of-the-barrel soup.

This is normal. This is ordinary.

Why?

No one gave speeches. No one demanded confessions in exchange for seconds.

Lights dimmed at night instead of bombs falling.

The ward breathed.

For the first time in months, Greta slept without waking every fifteen minutes to the sound of her own ragged breathing, convinced it was someone else’s. Her dreams were no kinder, but her body, at least, had been allowed to collapse.

Aara lay awake far longer. The quiet pressed on her ears. The warmth of the blankets wrapped around her dead legs, and the absence of sensation there scared her more than any artillery ever had.

She stared at the white ceiling and thought about propaganda.

She thought about posters that had shown British soldiers with leering mouths and bloody knives, about radio voices that had promised Allied troops would treat all Germans like vermin.

She thought about the hands that had lifted her, the food that sat warm in her belly, the clinical, indifferent care of the doctors.

Her worldview, which had already cracked under the bombs, now developed hairline fractures in places she couldn’t even see yet.

Morning brought with it clattering trolleys, muffled orders, and something that sounded dangerously like…routine.

Breakfast.

Bed checks.

Nurse Margaret—the stern-faced woman who spoke only odd shards of German—made her rounds, straightening blankets, checking bandages, adjusting pillows. Her English name sounded foreign in Aara’s head, but there was an odd comfort in attaching to this woman something other than “Sister” or “Nurse.”

She did not smile much. Her brow furrowed often. But her hands, even when brisk, never hurt more than they had to.

After breakfast, the tall doctor reappeared with a clipboard and the interpreter at his side.

“You will begin light occupational therapy,” he announced.

The phrase in German—Arbeits-therapie—made several women flinch.

“This is not labor duty,” he said immediately, hearing their silence and misreading it only slightly. “This is for your bodies and your minds. To prevent muscles from wasting away. To keep your thoughts from…going in circles.”

He could have said “to keep you from madness.” He didn’t.

The word “mobility” came up again. So did “capability.”

Later that morning, two orderlies wheeled Aara into a small room off the main ward.

A workbench had been set up there, lower than standard. On it sat piles of small items—gauze packets, rolls of surgical tape, wooden splint slats, little labeled jars of pills.

An American technician—judging by the accent and the shoulder patch—stood with his arms folded, consulting her file. He looked to be in his thirties. Tired, yes, but with that tethered energy of someone who liked to keep his hands busy.

“You were a signals operator, yeah?” he said, glancing up. “Good with organizing. Good with details.”

The interpreter relayed, stumbling through the English words.

“You have…Organization ability,” she translated. “That is what we need.”

The idea that anything about her was needed by anyone anymore landed on Aara like a small, unexpected weight.

She looked at the table.

Gauze in one pile. Tape in another. Splints leaning against one another like pick-up sticks. Chaos.

She knew chaos. She knew what to do with it.

Her fingers began to move almost before she consciously decided to cooperate.

Open each package. Check the size. Put like with like. Stack them neatly. Label them, in German and English if she could puzzle out the words.

The workbench became a little world she could control when everything else had been stripped away.

No one shouted if she made a mistake and had to resort. No one demanded she hurry. The American read a manual in the corner, occasionally glancing over, satisfied with the growing order.

Aara’s mind, which had been chewing on fear like gristle for days, found relief in the simple, repetitive motion.

Greta’s therapy room was brighter, but no less challenging.

A British orderly—no older than she was, hair cropped short, sleeves rolled up—stood at the end of the plinth, cradling her calf in his hands.

“We must keep the tissues pliable,” he explained, speaking slowly so she could catch at least the rhythm even if the words were hazy. The interpreter supplied the missing pieces. “We move the joints so they do not freeze. Understand?”

He flexed her ankle gently.

She watched.

She felt…nothing.

Her stomach heaved.

“Try to breathe with it,” he said, demonstrating exaggerated inhales and exhales. “Small effort is still effort.”

He moved her legs, his motions careful, attentive.

Greta’s eyes pricked with tears at the uselessness of her own body.

She waited for the sigh. The eye roll. The muttered English she wouldn’t understand but would feel anyway.

Instead, the orderly met her gaze and nodded once.

“Good,” he said. “You’re doing grand.”

She wasn’t doing anything. That he credited her anyway confused her in a way pain never had.

Liisa’s treatment was more complex.

They fitted her for a more permanent cervical collar and a full body brace that looked, in the workshop, like something out of a medieval torture chamber.

Straps. Buckles. Rigid plates.

The doctor walked her through each piece as they assembled it around her, translating in simple German.

“This will hold your neck,” he said. “So the broken bones do not move.”

“This will hold your shoulders.”

“This one, your upper spine.”

His fingers brushed her collarbone once, light, nothing more than contact.

“You have endured much,” he said, almost as an afterthought, in English. “We will give you the best chance we can.”

The interpreter, sensing something personal there, did not repeat it word for word. But Liisa saw the doctor’s eyes.

They did not see her as a warning. Or a failure. Or a burden.

They saw her as a…task.

An obligation.

It was an identity she hadn’t allowed herself to imagine.

Days passed.

The routine, strange at first, began to feel almost…safe.

They woke. Ate. Endured the small humiliations of bedpans and sponge baths. Worked at what they could. Rested under clean blankets.

The camp’s guard towers never went away. Nor did the barbed wire. If you looked outside the hospital windows, you still saw men with rifles walking patterns along the perimeter.

But inside, the structure was not built around punishment.

It was built around healing.

That, more than anything, disoriented them.

In a pause in her work one afternoon, Aara watched the British technician assembling a simple wooden wheelchair in the corner.

He checked the line of the wheels, squinted down the frame, adjusted the bearings, spun the rims, tightened the bolts, then spun them again.

She recognized that concentration. The way his hands moved, measuring force, feeling for resistance. She had seen that posture before, more times than she could count.

Not on a battlefield.

In a library in Berlin, where she’d once arranged books by subject and color, wanting them to be both useful and beautiful.

In her own movements as she’d laid out switchboard cables in perfect loops, hiding mess under polished functionality.

I used to care about things like that, she thought suddenly.

She realized she missed the version of herself who had not been exhausted all the way to the bones.

Greta, in a rare off-session moment, found herself near a window that overlooked the small yard at the center of the compound.

British soldiers were playing football there in their shirtsleeves, boots kicking up little sprays of dust. A guard tower loomed over one corner of the makeshift pitch, but the men below seemed unaffected. Laughter carried faintly through the open window.

One man slipped, landing hard. His mates stopped at once, hands extended, pulling him up, clapping his back, teasing him.

Fields of mud and blood and bodies had taught Greta to see uniforms as instruments. Tools. Cogs in a machine that had ground everything to rust.

She had not seen men…laughing.

“Off duty, lads,” her orderly said, following her gaze, misreading her expression as curiosity instead of grief. “Everyone needs a break.”

Everyone.

It sounded blasphemous to the part of her that had believed service meant obliteration.

Liisa’s first trip to the courtyard came on a day when the clouds broke.

They wheeled her out, brace strapped tight. The air smelled of damp earth and something faintly floral. It took her a moment to locate the source—the narrow strip of garden along the far wall, where someone had dared to plant flowers in a place defined by barbed wire.

Sun touched her face.

The world widened beyond the rectangle of ceiling that had been her horizon for weeks.

She inhaled slow, deliberate.

Her hands, resting on the arms of the chair, trembled.

In the evening, in the common room, the three women sat together for the first time where they could look at one another without craning necks.

Specialized chairs, yes. Cushions arranged just so. But they were upright. At a table.

Books in German sat on a side shelf, donated or confiscated, it was impossible to tell. Some of the other women picked them up, turning pages as if they’d forgotten how paper felt.

Others simply watched.

Aara had one of the thinner volumes open in front of her, but her eyes weren’t tracking the lines. Instead, they followed the tiny beats:

Greta’s head resting back, jaw unclenched, breath moving in and out without hitching.

Liisa’s shoulders, no longer held in that perpetual, rigid brace of bracing for impact.

Her own hands, lying still on the tabletop, not shaking.

Tension had not vanished. It had shifted.

Where fear had once sat, coiled and ready to strike at any kindness as a trick, there now coiled something more dangerous to everything they had been taught:

Doubt.

Gratitude felt like betrayal. To accept simple decency from the enemy seemed a kind of treason to all the speeches, the banners, the sacrifices.

“What if,” Aara thought, staring at the words on the page and seeing none of them, “they lied to us about everything?”

The question lodged somewhere under her breastbone and refused to be coughed up.

It would be a while before she dared say it out loud.

The morning they were told they were being moved again dawned bright and brisk.

There was a different kind of activity in the ward—charts being checked twice, bandages refreshed, braces tightened with extra care. The interpreter, now familiar enough to greet them with a nod instead of a stiff introduction, made the rounds with the doctor.

“You are being transferred,” she explained. “To a larger hospital. With specialists. Orthopedic, neurological. For long-term care.”

The words bounced around the room and landed in twenty different places.

“Specialists?” Aara repeated, cautious.

“The British army’s own,” the doctor confirmed. “They treat their wounded there. You will be wards of that hospital until you are fit to travel home.”

It was one thing to be stabilized in a converted camp, treated like an emergency that needed to be contained.

It was another to be told the enemy would devote permanent resources to you.

The modified ambulance that took them away was nothing like the lorry that had brought them.

Padded. Quiet. Springs that softened the bumps instead of amplifying them. Nurses who adjusted pillows mid-journey, checking pupils, murmuring reassurance.

They passed through countryside that looked less blasted than the regions near the front. Bombed bridges had been replaced by temporary spans. Fields, though scarred, showed hints of green.

It felt like traveling from one world into another.

The British military hospital rose up from the outskirts of a town like something from a different century.

Brick and glass and steel, all angles and clean lines. Not temporary. Not scraped together out of scavenged parts. A campus. Buildings connected by covered walkways. Lawns trimmed. Flowerbeds. Trees.

They were wheeled through corridors that smelled of polish and antiseptic.

And then into a ward that stopped them cold.

Beds lined both sides. IV poles, monitors, equipment Aara didn’t recognize. Nurses moving between them with efficient purpose. All of that was expected.

What wasn’t expected was who was in the beds.

British soldiers.

Young men. Old enough to be called men, at least. Some had hair still in the close-cropped military cut. Some had curls growing in over bandaged scalps. Some were missing legs, sheets folded carefully over empty space. Some had arms in slings, faces partially hidden by gauze. A few—like them—wore body braces, collars, the strange tools of a spine that would no longer carry weight on its own.

They were not hidden away.

They were laughing. And shouting. And crying openly when pain climbed too high.

The staff did not shush them. Did not move them behind screens.

Aara’s bed was parked across from one occupied by a British captain whose chest down was as still as stone.

He sat in a chair, his uniform blouse folded neatly on the bedside table, an odd device attached to the armrest—a mechanical claw of sorts, controlled by a series of cables and levers.

A nurse with her hair tucked under a cap adjusted the position of a box on the table. Inside were wooden blocks, each with a letter painted on it.

“Let’s spell your name again, shall we, Captain?” she said cheerfully.

The captain grinned crookedly. “As long as you don’t make me spell ‘Worcestershire’ again, Sister. That’s just cruel.”

The nurse laughed.

He focused on the device, manipulated it clumsily with his wrist. The claw closed over a block, lifted it, moved it, put it down. His face lit up like a boy’s.

He was not being pitied. He was being trained.

He was not an embarrassment. He was a project.

Dieter in Munich, Aara thought suddenly, remembering her father. Gassed, broken, sent home to limp in the shadows, always behind the brave stories.

Here, men like him were front and center.

Liisa watched as a private with paralyzed legs gripped a set of parallel bars, his knuckles white, sweat slicking his hair to his forehead.

“Come on, Tommy,” the therapist urged, one hand hovering at his back. “Weight through your arms. One foot forward. That’s it. Other foot.”

Tommy’s face crumpled. “I can’t,” he choked. “It’s useless.”

His mates—clustered at the end of the bars—leaned in.

“Don’t be daft,” one called. “You made it through the Scheldt, you can make it down that bloody bar.”

“Two inches, that’s all,” another added. “We’ll buy you a pint for every inch.”

The therapist kept his voice steady. “You are angry,” he said, as if diagnosing an engine. “That is all right. Be angry at me, but keep moving.”

Tommy, sobbing now, dragged one foot forward.

The room cheered.

They clapped for inches.

Liisa’s throat burned. Her own tears had been held back for so long they had grown barbs.

In the next bed over from Greta’s, an older soldier lay with both legs ending at the thigh. His wife sat on the mattress. Two children clambered over his blankets, arguing about who got to draw in his cast with a stub of pencil. At one point, the youngest pressed a sloppy kiss to the man’s cheek. He laughed, grabbed the child with his one good arm, and tickled him until they both wheezed.

Nobody shushed the children.

Nobody told them to go away so their father could be miserable in peace.

Greta watched the scene as if peering through glass at a life form she’d never seen.

In her own village, men had come home from the front in bits and pieces and been ushered into back rooms. Their missing limbs were not talked about. Their pain was a private matter, to be borne silently.

Here, it was…normal.

The woman noticed Greta’s gaze, offered a small nod. Not quite a smile, but something like solidarity.

Greta looked away quickly, shame and something else bubbling in her chest.

A nurse came to adjust her position.

“Are you all right?” she asked in simple, careful German.

Greta swallowed.

“Yes,” she lied.

What she wanted to say—but had not yet found the words for—was:

No. No, I am not all right. Because everything I was told about you people is unraveling in front of my eyes, and I do not know what to do with the pieces.

At some point that first afternoon, Aara noticed that the British staff treated her, Greta, and Liisa in exactly the same way they treated the British patients.

Same briskness. Same occasional jokes to break tension. Same frowns when a bandage had to be redressed. Same layout of pills in little paper cups on bedside tables.

The only difference was the language, and even that was being bridged by interpreters and common gestures.

If there was a policy of distinction, she could not discern it.

That was, in some ways, the hardest blow of all.

It would have been easier if there had been insults. If the doctors had said, “We do this because we are civilized, not like you,” or “Remember this when you think of your Führer.”

But no one used the word Führer at all.

Their treatment was not a morality play.

It was…medicine.

Recovery in a place like that was not a straight line.

There were days when a small improvement—a twitch of sensation, an extra degree of bend in a stiff joint—felt like victory. There were days when nothing went right, when spasms seized muscles that no longer obeyed, when pain behind the eyes or between the shoulder blades made even breathing feel like effort.

Through it all, the staff’s commitment did not waver.

Aara was introduced to an English language tutor who gave her simple exercises, recognizing that her mind needed work as much as her body did. It was odd, at first, to write words like “table” and “window” in another language, to hear her own voice wrap around foreign vowels.

She picked it up quickly. Signals work had trained her ear and her brain for patterns.

“Very good, Miss Aara,” the tutor said one day after she translated a form letter from English into German almost flawlessly. “You’ve a knack for this.”

He jotted a note in her file.

“Administrative potential,” it said in English. “Possible translation work.”

Greta, after weeks of guided movement, felt an unfamiliar sensation one morning when the orderly moved her foot.

“Did you feel that?” he asked, eyes sharp.

She hesitated.

Maybe she’d imagined it. The faintest kind of pressure. Like a finger tracing over a drawing of her leg instead of the leg itself.

“Yes,” she whispered. “I think so.”

He grinned. “Well, then. That’s something. Now we have to convince the rest of you to remember it.”

They added short sessions on crutches to her schedule, each step along the parallel bars a lesson in balance, fear, and stubbornness.

Liisa’s pain lessened by increments as the braces did their job.

She began to speak in full sentences again.

The doctors, recognizing the steel in her, spoke to her not as a fragile artifact but as a partner in her own care.

“These are your options,” one said, laying out sketches of surgical possibilities. “Each carries risk. We do nothing, you stay as you are. We attempt this, you may gain some stability, maybe some improvement. We attempt that, and the risk to your life is higher.”

No one had ever explained choices to her like that. Especially not about her own body.

“You decide,” the doctor concluded, through the interpreter. “We will abide by your decision.”

Liisa stared at the charts.

Her mind, rusty but still sharp, began to work.

She chose the option with lower risk and lower reward, because she had seen too much death to gamble what she had left.

They did not argue.

They scheduled the surgery.

In the months that followed, whispers of repatriation grew louder.

The war was truly over. Governments were rebuilding. Papers were being signed in conference rooms far away from beds where women painfully learned to sit up on their own.

The hospital staff treated the news with measured caution.

“Yes, you will go home,” Nurse Margaret told Aara when she asked. “No, we don’t know exactly when. Your bodies have to be ready, and so does your country.”

Ready for what, Aara wondered.

Ready to feed them? To house them? To look them in the eye?

Leaving the hospital, when it came, did not feel like release.

It felt like being removed from a bubble of clear rules and clean sheets and placed back into a world that had none.

Aara was given a wheelchair. Not one of the institutional ones. A custom-made chair, adjusted for her height, her arm strength, her needs. The metal frame shone in the thin sun the morning she was wheeled to the front of the hospital.

“Your chair,” the orderly said, almost proudly. “Yours, miss. Goes where you go.”

A stamp on a piece of paper bore the British Army crest and words in German that entitled her to medical supplies for a period after her return.

Greta received her crutches—size adjusted, rubber tips checked twice for grip—and a short letter from the orderly who had worked with her.

“Don’t stop,” he’d had the interpreter write. “On bad days, remember that the first step is always the hardest. You did that here. You can do it again.”

Liisa met with the doctor one last time.

He handed her a packet—thick, several pages, all in German.

“This is your medical history,” he said. “Detailed. Any doctor who reads it will know what was done, what is still needed.”

She flipped through. Each entry was dated, signed, noted with care.

“You did not have to write this,” she said quietly.

He frowned, not understanding.

“We had to,” he corrected. “Otherwise, the system fails.”

That was, she realized, the difference in a sentence.

To him, failure of the system was unthinkable.

To the men she had served back home, failure of people had been unremarkable.

The nurses and doctors assembled at the hospital entrance as the ambulances and trains were readied.

They did not line up to give stirring speeches. There were no flags waved. Only nods. A few awkward smiles. A couple of quick handshakes.

“Live well,” the doctor said to Liisa.

“We hope you find peace,” Margaret told her, the stern lines of her face softening just enough to reveal the woman under the routine.

The women were driven to a railhead, then loaded onto a train heading east.

The carriage they were in was clean. Not luxurious. But clean. Not packed with standing bodies. Just enough people for conversation if anyone had felt like speaking.

They watched the landscape change out the windows.

Fields grew poorer. Towns more shattered. By the time they crossed into what had been Germany proper, the damage was everywhere. Bombed-out factories like broken teeth. Bridges collapsed into rivers. Rows and rows of houses with their fronts torn off, rooms exposed to the sky like dollhouses.

The smell seeped in.

Not disinfectant, not polish.

Ash. And something sour, behind it. A nation that had burned itself from the inside.

At last, the train squealed to a stop in a station with half its roof missing.

Announcements were made. Papers checked. Passengers separated into lines based on destinations that no longer sounded like real places.

The women went their separate ways.

Aara’s Berlin was rubble.

Streets she had walked as a girl were now jagged canyons of brick and twisted metal. The apartment building where her parents had lived had taken a direct hit. A basement shelter was all that remained, and there were no bodies to mourn properly. Only whispers from neighbors about “that night” and shrugs.

She found a room in a crowded flat—three families to an apartment—and rolled her British-made chair up and down stairways with the help of whoever happened to be around. Her arms, strengthened by months of propelling herself through hospital corridors, obeyed her.

Work, amazingly, found her.

There was a need for anyone who understood both German and English, who could file, organize, translate the flood of forms coming in and out of provisional government offices and Allied headquarters.

She sat at a battered desk, the legs of her chair scuffed by the concrete, and typed letters that began “To whom it may concern” and “In reference to your request.”

She watched the men around her—former Party members trying to reinvent themselves, women worn to shadows by hunger, Allied officers with tight mouths and tired eyes.

She insisted on proper forms. Clear signatures. Accurate records.

She insisted, quietly but firmly, on not allowing people to disappear into corners because their stories were uncomfortable.

She had been given dignity by an enemy.

She would not be stingy with it now.

Greta’s village had not been bombed.

The war had simply…rolled past and taken everything with it.

The farm her parents had worked was a patchwork of cratered fields and collapsed barns. The cows were gone. The chickens, too. The house still stood, but with a roof that sagged in the middle like a man’s back after too many hard winters.

Her mother met her at the lane, hands fluttering, eyes wide with the double shock of seeing her daughter alive and seeing her daughter leaning on crutches.

“You’re home,” she said, voice cracking. “Praise God. You’re home.”

Greta hugged her awkwardly, the crutches clattering.

She had been afraid she would be treated as a burden. Another mouth to feed in a place with no food. Another problem for an old woman with a bent back and weak lungs.

Instead, her mother insisted she retire to a chair in the corner.

Greta refused.

She had not spent months fighting her own body just to sit still and watch others move.

She began where she could begin: the earth behind the house.

Small, careful steps. Crutches biting into soil. Each swing of her leg a reminder of the British orderly’s voice: Small effort is still effort.

She cleared a patch. Dug with a hand trowel. Planted seeds scrounged from neighbors or saved from the last thin harvest.

The soil did not care that she moved slowly. It did not judge the unevenness of the furrows.

It only answered what it had always answered:

Effort.

Days grew into weeks. Shoots appeared. Her mother laughed out loud the first time she saw green push up through the brown.

Greta slept at night with the smell of dirt under her fingernails and the ache of honest work in her shoulders.

She still woke sometimes with the ghost sensation of legs that didn’t move.

But when she swung herself out of bed in the morning, she had somewhere to go besides the chair in the corner.

Liisa settled in a small town that had managed, by some accident of geography or fortune, to escape the worst of the bombing.

A distant relative had a spare room. It was up one flight of stairs. By the third day, routines had formed: a neighbor boy would come in the morning, help her navigate down, and come again at dusk to help her back up.

She hated the dependence.

She also cherished the fact that help came not with a lecture, not with a demand, but with casual normality.

“You’ll get the hang of it yourself soon,” the boy said once, grinning. “You’re stubborn.”

She was.

She taught herself tricks with her hands—how to lift and turn with the strength of her arms, how to slide from chair to bed without wrenching her neck. All the little maneuvers the British occupational therapists had drilled into her now became part of her daily vocabulary.

She did not praise the British openly. That would have been unwise in a town still nursing its resentments.

But when neighbors began to mutter bitterly about “what they did to us” and “how they humiliated us,” she would say, “They also built hospitals.”

When someone called Allied soldiers monsters, she would reply, “The monsters I knew did not sit for hours moving a stranger’s legs back and forth so the muscles would not die.”

Her voice was low. But it carried.

The world moved on.

Maps were redrawn. Alliances shifted. Newspapers found new enemies to caricature.

No headline ever read: WOUNDED GERMAN WOMEN RECEIVE UNEXPECTED CARE FROM BRITISH ARMY. No treaty included clauses on minimum dignity owed to defeated foes.

History, in its official narratives, cared more about conferences and front lines.

But the three women, and dozens like them, carried something back to their broken country that could not be measured in borders.

They had gone into captivity convinced that strength was brutality, that mercy was weakness, that enemies were less than human.

They came out with a different, more dangerous knowledge:

A nation’s true power is revealed not in how it kills its enemies, but in how it treats them when they can no longer stand.

They had expected torment.

They had expected humiliation.

They had braced themselves to become symbols of defeat.

And instead, they had been turned—slowly, carefully—back into people.

Years later, Aara would wheel herself through the corridors of whatever office she was working in, her chair’s metal gleaming dully in the fluorescent light, and she would pause when she saw someone being dismissed because they were inconvenient.

She would think of Margaret’s stern face softening as she said, We hope you find peace.

Greta would bend over her garden—older now, hands more gnarled, but steady—and teach a neighbor’s child how to push a seed into the earth.

“You don’t need to be perfect to make things grow,” she would say. “You just need to show up.”

Liisa would sit in her chair by the window, brace long gone but posture still straight, and watch the children in the street gathering around a man on crutches, asking him questions, not recoiling.

She would think of a British captain learning to use a mechanical claw, and of the way his mates had made space for both his grief and his laughter.

No statues would ever be raised to the British sergeant who had said, “Right then, ladies,” instead of sneering. Or to the doctor who had written long notes in careful German for an enemy’s future physician. Or to the orderly who had held a paralyzed German girl’s legs and said, “Good, that’s something.”

But in their small, stubborn lives, the women made a kind of monument anyway.

They refused to forget.

They refused to return fully to a worldview that measured worth in hardness alone.

The quiet realization that had begun in a British truck in the rain, and deepened in a ward filled with the wounded of both armies, stayed with them to the end of their days:

Humanity can survive even on a desolate stretch of road in a defeated country.

And sometimes, the ones who remind you of that are the very people you were taught to hate.

THE END

News

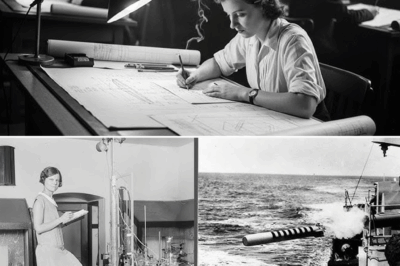

CH2 – The Female Engineer Who Saved 500 Ships With One Line of Code

By the winter of 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic sounded like a broken heartbeat. Convoys vanished off the map…

CH2 – How One Mechanic’s ‘CRAZY’ Trick Let Him Fight 50 Japanese Zeros ALONE — And Saved 1,000 Allies…

At 8:43 on the morning of August 15th, 1943, First Lieutenant Kenneth Walsh watched his wingman scatter across the…

CH2 – How One Crewman’s “Mad” Rigging Let One B-17 Fly Home With Half Its Tail Blown Off

At 20,000 feet above the Tunisian desert, the tail of All-American started to walk away. Tail gunner Sam Sarpalus felt…

CH2 – German Sniper’s Dog Refused to Leave His Injured Master — Americans Saved Him…

The German Shepherd would not stop pulling at the American sergeant’s sleeve. It had started subtle: a tug at the…

CH2 – The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men

The German officer’s boots were too clean for this part of France. He picked his way up the muddy slope…

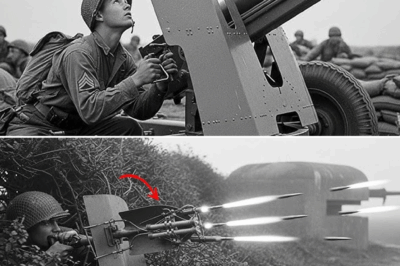

CH2 – This 19-Year-Old Was Manning His First AA Gun — And Accidentally Saved Two Battalions

The night wrapped itself around Bastogne like a fist. It was January 17th, 1945, 0320 hours, and the world, as…

End of content

No more pages to load