Part One:

The first time I met the old man at the blue house, it was one of those February nights when the cold sneaks through your jacket no matter how tightly you pull it shut. I was nineteen, broke, and working delivery for Tony’s Pizza to help Mom with rent. My Honda Civic coughed like a smoker every time I started it, and the heater worked about half the time, but it got me through my Thursday-night route.

The blue house sat at the very end of Maple Street, past where the streetlights thinned out and the pavement turned to cracked gravel. It looked like it hadn’t been painted since Reagan was in office—weathered boards, sagging shutters, a mailbox that leaned like it had given up trying to stand straight.

When the door opened, warm air rushed out, carrying the smell of coffee and something older—like paper and cedar. The man who stood there looked like he’d stepped out of another decade. Gray cardigan, neatly pressed khakis, silver hair combed back, and eyes so sharp they made you forget he was probably pushing eighty.

“That’ll be $18.50, sir,” I said, trying not to shiver.

He handed me three twenties and a five—then waited while I counted. “Sir,” I said, confused, “this is sixty-five dollars.”

He gave a faint smile, like he already knew I’d say that. “It’s correct. Keep the change.”

I blinked. Forty-seven bucks in tips—for one pizza? I thought maybe he’d made a mistake. “Are you sure, sir?”

“Yes.” He met my eyes with unsettling calm. “And tell your mother I’m sorry.”

Before I could ask what that meant, he shut the door.

I stood there with the box still warm in my hands, my mind tripping over those words. Tell your mother I’m sorry.

That night, I mentioned it to Mom. She was still in her scrubs, eating leftover Chinese food at the kitchen table, exhaustion written all over her face. “You ever know a guy named Voss? Lives over on Maple?”

Her chopsticks froze midair. It was only for a second, but I noticed.

“Why?” she asked, voice tight.

“He ordered pizza. Big tip. Said to tell you he’s sorry.”

Mom set the container down carefully. “He’s probably confused, sweetheart. You know how older folks can get.”

She went to bed early that night, leaving her dinner half-eaten. That never happened. Mom didn’t waste food. Or words.

By the fourth Thursday, I realized this wasn’t a mistake.

The order was always the same: one large pepperoni, extra cheese, nothing else. The routine never changed either—$18.50 for the pizza, $47 tip, and the same five words before the door closed. Tell your mother I’m sorry.

After the fifth week, curiosity started itching in the back of my brain.

“Mom,” I said one night while she folded laundry, “that Mr. Voss guy keeps saying the same thing every week. You’re sure you don’t know him?”

She slammed the iron down harder than she needed to. “Colton, some things are better left in the past.”

“But what if he owes you something? Or thinks he does?”

“What he owes or doesn’t owe isn’t our concern.” Her voice was clipped. “You deliver the pizza, take the money, and come home. Promise me.”

There was something about the way she said promise me—like she was asking for more than obedience. Like she was asking me not to reopen a wound she’d spent years closing.

I promised.

But I still kept delivering. Every Thursday at 8:15 sharp, my Civic would roll down Maple Street, headlights cutting through the dark, leading me to that peeling blue house.

And every Thursday, the same exchange.

Until week twenty-four—when everything changed.

That night, the porch light was off.

I remember standing there, pizza box in hand, staring at the darkness. Usually, he’d already be waiting by the door. I knocked once. Then again.

Finally, the door creaked open.

He looked worse. Paler. Thinner. The cardigan hung loose, and the tremor in his hands was worse than usual. His eyes, though—his eyes were still sharp, studying me like he was trying to memorize my face.

“Mr. Voss,” I said, “you okay? You look—”

He waved it off. “Just tired, son. That’s all.”

He handed me the usual bills—exact change plus forty-seven dollars.

But instead of closing the door, he hesitated. “You have her eyes,” he murmured.

I frowned. “Whose eyes?”

“Your mother’s. The same brown with gold flecks when the light hits.” His voice cracked a little. “Used to tell her they looked like autumn leaves with sunlight caught inside.”

A chill ran down my spine.

“You really knew her, didn’t you?” I asked quietly.

He nodded once. “Better than anyone.”

Something deep in my chest shifted. “Mr. Voss… who are you?”

Instead of answering, he reached into his cardigan and pulled out a small brass key. It looked old, the kind of thing that might open a grandfather clock or a locked memory.

“Next Thursday,” he said, pressing it into my palm, “if I don’t answer the door—use this. Second door on the left. Mahogany desk. There’s a drawer. Inside you’ll find answers to questions you haven’t asked yet.”

My hand closed around the key. “What’s this about?”

He sighed. “Because I might be wrong. Or I might finally be right. Either way, the truth is in there.”

“Sir, you’re scaring me.”

He looked at me, voice suddenly firm. “Promise me you’ll come. Whatever happens, promise me you’ll look.”

I hesitated. Then nodded. “I promise.”

His grip tightened on my wrist, surprising for how frail he looked. “And whatever you find, son… share it with your mother.”

That word again—son.

He let go, leaning against the doorframe. “Now go. It’s late.”

The door closed.

And I stood there, staring at the brass key gleaming in my palm under the streetlight, feeling like I’d just been handed the start of a secret that had been waiting nineteen years to be told.

That night, I couldn’t sleep. The key sat on my nightstand, catching the moonlight. Mom had already gone to bed, but I could hear her tossing in her room—like she felt the same disturbance in the air I did.

By Tuesday, I couldn’t take it anymore. I drove past the blue house. The lights were off, but through the curtain, I thought I saw movement.

He was still alive. For now.

That evening, Mom was folding laundry again, humming softly. Sunlight streaked through the window, catching in her dark hair—streaked with the faintest hint of silver now.

“Mom,” I said quietly, “we need to talk about Hendrickk Voss.”

The shirt slipped from her hands.

“Colton,” she whispered, “please don’t.”

“He’s sick. He gave me a key to his house. Said the truth is in his study. He said you deserve to know.”

She sank onto the couch, staring at her hands.

When she finally looked up, her eyes weren’t angry—they were tired, ancient.

“Your father’s name was Henry,” she said. “Henry Colton Dawson. Everyone called him Henry except me. I called him Henrik sometimes. Because I loved how it sounded.”

The world tilted.

“You told me he died.”

“He did,” she said softly. “At least… the part of him that remembered us did.”

Part Two:

When I was little, I used to ask Mom about my dad. She’d always give the same short, tidy answer. He died before you were born, sweetheart. No details, no photos, no family stories.

As a kid, I accepted that. As a teenager, I stopped asking. But now, with the brass key burning in my pocket and her saying his name out loud for the first time in my life, I realized how little of my own story I actually knew.

“Mom,” I said carefully, “are you saying Mr. Voss is actually… Henry Dawson? My father?”

Her voice trembled. “I don’t know, Colton. I don’t know what to believe yet. But if he’s remembering enough to find you—if he’s using the name Voss—then maybe his memory’s been coming back slowly. Maybe he’s been trying to find us.”

I tried to piece it together. “Then why would he pretend to be someone else?”

“Maybe shame,” she whispered. “Maybe guilt. Maybe he just didn’t know how to tell us.”

She stood up suddenly. “Get your keys. We’re going now.”

“Mom, it’s not Thursday yet.”

“If that man is your father,” she said, her voice fierce with something between fear and hope, “then we’re not waiting another day.”

We drove in silence. The sky was a bruised purple, clouds smeared thin by the wind. Maple Street was quiet, almost too quiet. No porch lights, no movement behind the curtains.

When we pulled into the cracked driveway, Mom hesitated before opening her door. “I don’t know if I can do this,” she whispered.

“You’ve waited nineteen years,” I said softly. “You can do this.”

She nodded, exhaled slowly, and followed me up the creaking steps.

I knocked three times, like always.

“Mr. Voss?” I called. “It’s Colton. I brought someone with me.”

For a moment, only silence. Then a faint voice: “Door’s open. I’m in the living room.”

Mom’s fingers tightened around mine as we stepped inside. The air smelled like coffee and cedar, same as always, but fainter now, as if even the house was running out of strength.

He was sitting in his armchair under a soft lamp, a blanket over his lap. The gray cardigan hung loose on his frame, his skin pale and thin. But when he looked up and saw Mom, something changed.

His entire face lit up.

“Judy,” he breathed. “My Judy.”

Mom’s hand flew to her mouth, and she let out a sound halfway between a gasp and a sob. “Henry…?”

He nodded, tears welling instantly. “Started coming back about a year ago. Pieces at first—music, laughter, the smell of coffee, the way you used to hum Beethoven while you studied. Then faces. Your face.”

She knelt beside him, her hands trembling as she took his. “Henry, I thought you were gone. They told me you didn’t remember me. That trying to remind you would hurt you.”

He reached out, brushing a lock of hair from her cheek. “It did hurt. But not remembering you hurt worse.”

I stood frozen, watching the two of them—the ghost story that raised me and the woman who never stopped mourning—finally occupying the same space again.

“Henry,” Mom whispered, “this is our son. Colton.”

He turned to me, eyes wet but sharp. “I know. I’ve known since the first night I saw him.”

My throat closed up. “You… you knew?”

He nodded. “You walked up my steps in that jacket two sizes too big, shivering but still smiling, and I saw her eyes. My heart knew before my mind did. But I couldn’t just say it—not until I was sure. Not until I remembered everything.”

I swallowed hard. “That’s why you said those words. ‘Tell your mother I’m sorry.’”

He smiled sadly. “Because that’s all I could offer until now.”

We sat there for a long while, letting the silence fill what words couldn’t. The room glowed with soft light, and for a moment, time seemed to fold in on itself—nineteen years gone, but not wasted.

Then Henry’s voice broke the stillness. “There’s something I need to show you both. The study. Second door on the left.”

He motioned for me to use the key.

The hallway was lined with framed sheet music and old photographs. I unlocked the study door, and the smell of dust and cedar hit me instantly. Bookshelves lined the walls, and in the center stood a heavy mahogany desk.

The drawer opened with a faint click. Inside were letters—dozens of them, all addressed to “Judy” in neat, careful handwriting. Some yellowed with age, some recent, written on hospital stationery and cheap notebook paper alike.

Mom stepped beside me, her hand trembling as she lifted the top one.

My Dearest Judy,

If you’re reading this, it means I’ve found the courage I never had when I should have. I remember pieces of us—music, laughter, promises. And though my mind betrayed me, my heart never did. It’s been thirty years, but I’m starting to remember our song.

Her breath hitched.

I thumbed through more envelopes. Tucked beneath them were newspaper clippings—my high school graduation, Mom’s promotion at Mercy General. A photograph of me on my first day at Tony’s Pizza. Notes scribbled on the back in his shaky handwriting: He looks just like me at nineteen.

My chest tightened.

He’d been watching us—quietly, respectfully—trying to bridge the gap between what he’d lost and what was still waiting.

“Mom,” I said softly, “he’s been keeping track of us. All these years.”

She pressed the letter to her chest, tears slipping silently down her cheeks.

When we returned to the living room, Henry was still in his chair, the blanket pulled high, eyes half-closed but alert.

“Find it?” he asked.

Mom nodded. “You remembered everything, didn’t you?”

“Not at once,” he said. “At first, it was just fragments. But then I saw him—our son—and it all came rushing back like a dam breaking.”

He motioned weakly toward the corner. “There’s one more thing.”

I followed his gaze. A violin case leaned against the piano. I carried it to him, and he unlatched it with trembling fingers.

Inside, the instrument gleamed like honey under the lamplight.

“This was mine,” he said. “Before the accident, I played piano mostly. But the violin was my first love. When I finally remembered how to play again, I realized something.”

He looked at me.

“It was meant for you.”

“Me?”

He nodded. “Your hands. Long fingers, like mine. You may not know music yet, but it knows you.”

He handed me the violin, and it felt alive in my hands.

“Keep it,” he said. “It belongs in this family again.”

I looked at him, overwhelmed. “Mr.—Henry—why wait all this time? Why not find us sooner?”

“Because I didn’t remember who I was,” he said simply. “When I woke from the accident, the doctors told me I was someone named Hendrickk Voss. They said my fiancée left. My parents made sure of that story. They thought they were protecting me. Maybe they were. But when I started to remember her—your mother—I didn’t know if she’d still want to see me. I’d been gone thirty years.”

Mom’s voice broke. “You were the love of my life, Henry. You still are.”

He reached out, gripping her hand. “Then maybe we can finish what we started.”

We spent the next hour talking—about music, memories, the years lost. He told me about the accident: a spring storm, a semi-truck jackknifing on the highway, and two months in a coma that erased a lifetime.

“They told me I was lucky to be alive,” he said, voice soft. “But for thirty years, I felt like a ghost wearing someone else’s skin.”

Mom wiped her eyes. “All that time, I thought you were dead.”

“In a way, I was.”

The clock ticked softly in the corner, steady and patient, like time itself was holding its breath.

At last, Henry leaned back, tired but peaceful. “Colton, come closer.”

I did.

“Your name,” he said, “your mother gave you my middle name, didn’t she?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Colton Henry Reeves.”

He smiled faintly. “She gave me a piece of myself back through you. You were the bridge between what I was and what I lost.”

He looked at Mom again. “And you—you never stopped waiting.”

She shook her head, tears glimmering. “I thought I had. But maybe waiting was the only thing I ever really did.”

The old grandfather clock struck midnight. Henry looked at both of us, his expression gentle but determined.

“There’s something else,” he said. “A truth I need to say before it’s too late.”

He motioned for me to sit beside him. “Your mother named you after me, son.”

Seven words. Simple. But they hit like thunder.

I froze, the violin slipping from my hands and thudding softly against the carpet.

For a second, nobody moved. The air itself felt charged, thick with everything those words meant.

“Henry Colton Dawson,” he said quietly. “She reversed it. Colton Henry Reeves. She kept me alive in your name.”

I stared at him, heart pounding. “You’re my father.”

He smiled through tears. “Always have been.”

Mom sobbed then—full, unrestrained, years of silence breaking all at once.

He opened his arms, and she fell into them. I joined them, and for the first time in my life, I felt what a family hug was supposed to feel like—messy, warm, and entirely real.

Henry passed two weeks later. Peacefully.

But in those two weeks, he gave us back thirty years.

Mom took leave from the hospital, and we practically moved into the blue house. Every morning, she made breakfast while I brewed coffee. We filled the hours with stories—his about the lost years, ours about the life he’d missed.

He showed us his study, the photos, the journals, the half-written letters he’d never mailed. He taught me the basics of violin, his hands guiding mine like we’d been doing it forever.

At night, Mom would play the piano, and we’d fill that little blue house with the music they once dreamed of making together.

When he was too weak to play, he’d just listen, smiling with eyes closed.

“You have her rhythm,” he’d tell me. “But my stubbornness.”

Mom would laugh softly. “He definitely got that from you.”

Those were the best days of my life. Short, but infinite.

He died on a Sunday morning in April.

Mom was holding his hand. I was in the kitchen, tuning the violin. He opened his eyes, whispered something I’ll never forget—

“Don’t stop the music.”

Then he was gone.

The funeral was small. Family we barely knew, a few of his old music colleagues, neighbors from Maple Street. Mom played Clair de Lune on the church piano—the same song he’d played when they first met. I played beside her, clumsy but steady.

The obituary read:

Henry Colton Dawson — beloved husband, devoted father, musician, reunited with his family after thirty years apart.

Afterward, Mom and I went back to the blue house. The sun was setting, washing the sky in gold.

She turned to me, brushing away a tear. “You know,” she said, “he used to say that love doesn’t die. It just waits for us to remember it.”

I nodded, gripping the violin case. “Then I guess he finally remembered.”

Part Three:

Grief has a strange way of reshaping time.

The two weeks after Henry’s funeral felt both endless and fleeting. Every corner of the blue house held an echo of him — a coffee cup left by the sink, his glasses resting on a stack of piano music, the indentation on his armchair that hadn’t faded yet.

Mom couldn’t bring herself to sell the place right away.

“It still feels like he’s here,” she said one morning as sunlight streamed through the curtains. “Like if I turn around quick enough, he’ll be sitting right there.”

I didn’t argue. I felt it too.

Every Thursday, at exactly 8:15 p.m., I’d still catch myself glancing toward the driveway, half-expecting to see his silhouette waiting by the window for his pizza — the ritual that had unknowingly built the bridge between us.

It took me a while to realize the ritual wasn’t about the pizza at all. It was about connection. About holding onto something small and ordinary when the extraordinary feels impossible.

Mom spent her days sorting through boxes in the study. Old sheet music, faded photographs, a stack of journals filled with his neat, looping handwriting. She’d pause now and then to read something, her expression softening, then breaking.

I tried to give her space.

But one evening, she called out, “Colton, come look at this.”

She was sitting cross-legged on the floor beside the mahogany desk. In front of her was a cardboard box labeled Letters (Unsent).

I knelt beside her.

“These were in the bottom drawer,” she said. “He must’ve written them after the accident, but before his memory came back fully.”

I picked one up. The envelope was yellowed, corners frayed. Inside, the letter began in shaky handwriting:

My Dearest Judy,

They told me today that I was engaged once. I asked to whom, but no one would tell me. My parents said it doesn’t matter now, that my mind needs rest. But at night, I hear music. A melody I can’t place. It feels like a memory I’ve lost, or a promise I’ve broken. If I ever find the woman who inspired that song, I’ll spend whatever years I have left apologizing.

Mom wiped a tear. “He wrote that three months after waking from the coma.”

I read another.

June 1989

I saw a nurse today who reminded me of someone. Brown eyes, kind smile. When she laughed, I felt a pain so sharp I had to excuse myself. My mother says I should stop chasing ghosts, but what if the ghost is my heart trying to find its way home?

I set the letter down, throat tight. “He never stopped searching for you.”

She nodded slowly. “Even when he didn’t know who I was.”

For weeks, we kept finding fragments of him — old photographs of college recitals, ticket stubs, a program from a concert he’d played the night before the accident. Each discovery felt like piecing together a puzzle whose final image we already knew but still couldn’t stop assembling.

And then one day, I found something that changed everything again.

I was in the attic, sorting through boxes labeled Music Archives. Most of it was dusty sheet music and old concert flyers. But one folder caught my eye — labeled April 7.

Inside were photocopies of wedding invitations, music selections, even a sketch of a small church with handwritten notes about seating arrangements. At the bottom of the stack was a single-page letter, typed, unsigned:

To My Judy,

If something ever happens and I don’t come back, promise me you’ll keep playing. Don’t let the music die just because I did. Music is our bridge, even if memory fades. Wherever I go, it will find me. I love you — Henry.

I carried the letter downstairs and handed it to Mom.

She traced the words with her fingertips, then whispered, “He wrote this before the accident. The night before our wedding.”

Tears welled in her eyes, but this time they were warm, not broken. “He was always so certain that love outlived everything — even death.”

As weeks turned into months, we settled into a rhythm again.

I still worked at Tony’s Pizza part-time. Thursday nights, I couldn’t bring myself to skip the shift. It felt wrong not to.

The new family that bought the blue house were kind — a young couple, Mark and Elise, with twin daughters who liked to chase fireflies in the yard. They ordered Hawaiian pizza every week, extra pineapple.

The first time I delivered to them, Elise smiled. “You used to deliver here before, didn’t you?”

“Yeah,” I said, my voice catching slightly. “For a long time.”

Mark looked around. “It’s a beautiful old place. The man who lived here before left a piano and a violin. Said they belonged to the house.”

I smiled faintly. “Yeah. They did.”

When I got back to my car, I sat there for a long time, listening to the girls laughing through the open window. The sound drifted through the same doorway where Henry once waited, and I felt this strange peace — like the house itself was healing, too.

Mom and I moved Henry’s piano into our living room. The violin, now mine, sat in a stand beside it. At first, I could barely play. But with every lesson he’d given me still echoing in my head, I practiced.

By summer, I could manage a few songs without making the neighbors hate me.

Mom would listen while making coffee or reading in the kitchen. Sometimes, I’d catch her humming along softly, eyes far away.

One evening, she set down her mug and said, “You know, he always believed the universe works in echoes. That what we lose eventually finds its way back — through sound, through people, through time.”

“I think he was right,” I said, bowing the violin gently. “The pizza was the echo.”

She smiled. “Maybe so.”

Then came April 7th — their would-be wedding day.

Mom wore the same silver necklace she’d worn every day for as long as I could remember, the one she used to keep tucked beneath her scrubs. I’d never realized until Henry mentioned it that it held her old engagement ring.

We decided to spend the evening quietly — no big gestures, no heavy talk. Just music.

“Play with me,” she said, sitting at the piano.

I picked up the violin.

The first notes were hesitant. Then smoother. The melody was Clair de Lune — the song that brought them together all those years ago.

Mom’s eyes glistened as she played. “He said this song sounded like sunlight breaking through clouds. He played it the night he asked me to marry him.”

As the final note faded, the room felt full — not with sadness, but with something bigger. Presence.

“I think he’s here,” she whispered.

“I know he is.”

After that, Thursdays changed.

They weren’t sad anymore. They became a reminder — a rhythm of memory and forgiveness.

Tony, my boss, still hollered from the kitchen, “Colton, your regular’s online two!” even though the old address now belonged to someone else. It became a joke between us.

I’d just grin, toss on my jacket, and say, “On it, boss.”

Sometimes life needs rituals to hold its shape.

One night, about three months after Henry passed, I found another envelope tucked inside the violin case. His handwriting was still firm, though the paper had yellowed slightly.

Colton,

If you’re reading this, it means I didn’t get to tell you everything in person. The $47 wasn’t random. It was the date — April 7th — the day your mother and I were supposed to get married. I wanted you to remember that number, to ask what it meant, because I knew she’d tell you when she was ready. I couldn’t give her the wedding I promised, but I could honor it one Thursday at a time.

You turned those deliveries into more than pizza runs. You brought me back to life, son. Never forget that. When you play the violin, you’re continuing what we started — music as memory, love as legacy. And if you ever doubt whether the universe notices you, remember how it brought a father and son together through a box of pepperoni pizza. That’s proof enough.

Love always,

Dad.

The word Dad hit harder than I expected.

I’d said it once to him — softly, awkwardly, the day before he died. He’d smiled, patted my shoulder, and said, “Took us nineteen years to get there, but worth the wait.”

I read the letter three times before showing it to Mom. She cried for a long time, then laughed through the tears. “Only Henry would turn a pizza tip into a love letter.”

That summer, we hosted a small memorial concert at the community center. Mom played piano; I played violin. We invited some of Henry’s old music friends, and Tony sponsored the pizza for everyone afterward — “large pepperoni, extra cheese,” just like Henry always ordered.

Halfway through the performance, I looked up and caught Mom’s eye. There was something in her expression — peace, maybe. Or completion.

When the last note faded, the audience rose to their feet. Not in thunderous applause, but in quiet respect.

Afterward, an older man approached us. “I played with Henry back in the day,” he said. “He used to talk about a girl who made him believe music could heal the soul. Looks like he was right.”

Mom smiled softly. “He always was.”

That night, we sat on the porch under a sky full of stars. The air was cool, the kind of early summer night where everything feels suspended — grief, love, hope.

Mom leaned her head on my shoulder. “You know,” she said, “there was a time when I thought the universe had taken everything from me. But now I see it just… stored it. Waited until we were ready.”

I nodded, looking up at the stars. “And when we were ready, it gave it all back.”

She smiled. “Exactly.”

We sat there quietly for a long while, listening to crickets and the faint hum of a distant train.

Then she said, almost to herself, “He’d be proud of you.”

I swallowed hard. “I hope so.”

“He would. You brought him home.”As the months rolled on, I started college full-time, majoring in music education. It felt right — like closing the circle Henry started.

Mom returned to work at the hospital, lighter now, carrying a peace I’d never seen in her before. Sometimes I’d catch her humming while cooking, a tune that sounded suspiciously like Clair de Lune.

On the anniversary of his death, we drove out to Maple Street. The new family had planted flowers along the walkway. The paint on the shutters was fresh, and the mailbox stood straight again.

I placed a single white rose on the porch and whispered, “Thanks for the music, Dad.”

The wind picked up, carrying the faint scent of cedar and coffee.

For a moment, I could’ve sworn I heard the faint sound of a violin drifting through the evening air.

Grief doesn’t end, I’ve learned. It just changes shape — becomes something quieter, something you can live beside without drowning.

And sometimes, on Thursday nights, when I pull up to a stranger’s house with a pizza box in my hands, I’ll catch myself smiling.

Because once upon a time, a lonely old man tipped me $47 every week and said five strange words that made no sense until they changed everything.

Tell your mother I’m sorry.

And now, every time I play the violin, I answer him back —

She forgave you. We both did.

Part Four:

By the time the second year passed after Henry’s death, life had begun to look almost ordinary again—except for the way the ordinary now glowed around the edges, like light spilling through a cracked door.

I was twenty-one, working part-time at Tony’s, full-time at community college. I taught beginner violin lessons at the youth center on weekends, mostly to kids whose parents couldn’t afford private tutors.

Mom said Henry would’ve been proud. “You’re giving back with music,” she’d tell me. “That’s exactly what he wanted his life to mean.”

Most nights, I still practiced on the same violin he’d handed me that last evening in his living room. The honey-colored wood had a warmth that never faded, even when the room was cold. Every time I drew the bow across the strings, I could almost feel his hands guiding mine—steady, patient, unhurried.

Tony still refused to change my Thursday shift. “You’re the only one who never screws up deliveries,” he’d grumble, flipping dough behind the counter.

I think he understood there was something sacred about Thursdays for me.

The new owners of the blue house—Mark and Elise—became regulars. Their twin daughters, Lily and June, would run out barefoot to meet me, squealing like they’d never seen pizza before.

“Did you bring the pineapple one?” Lily would ask every week, already knowing the answer.

“Of course,” I’d grin. “Same order, same time.”

When I handed Mark the box, he always tipped me five bucks and said, “We’re keeping the tradition alive, right?”

I never told him what the tradition really meant. Some stories don’t need explaining. They just need living.

One night in early spring, Mom came home from the hospital with a letter clutched in her hand. Her cheeks were flushed in that rare way that meant excitement instead of exhaustion.

“Colton,” she said, “you’re not going to believe this.”

It was from the Midwestern Conservatory of Music, inviting me to audition for their transfer program.

I’d sent an application on a whim months earlier, encouraged by one of my students’ parents. I never thought I’d actually get a reply.

“They want you to audition with your own piece,” Mom said, eyes shining. “Something original.”

That night, I sat in my room staring at the violin on the stand. My own piece.

Without even thinking, I began to hum the melody Mom used to hum when she cooked—soft, circular, unfinished. It was the same melody Henry had once called our bridge.

So I built on it. Added fragments of Clair de Lune, bits of Henry’s favorite ragtime rhythms, pieces of my own heartbeat woven between the notes.

I called it April Seventh.

Writing music is like talking to ghosts. Every note you put down feels like a conversation with someone you can’t quite see.

For weeks, I worked on April Seventh. I’d wake up at dawn, scribble notes before class, practice late into the night while Mom read in the next room.

Sometimes she’d poke her head in. “That part there,” she’d say, pointing to a measure. “It sounds like him.”

“I know,” I’d reply. “It’s supposed to.”

The song became our shared language again—the one we’d lost for decades.

By the night of the audition, I felt ready.

The conservatory’s recital hall smelled like polished wood and old ambition.

Students with violin cases and nervous smiles filled the waiting area.

When my name was called—Colton Henry Reeves—I felt a jolt of pride and ache all at once.

The stage lights were blinding, but comforting too—white and steady, like the light that had filled Henry’s living room that last night.

I lifted the bow.

The first note wavered, then steadied.

The melody unfolded like a story retold: hesitant, hopeful, rising into something that felt bigger than sound.

When I reached the bridge—the part I’d written for him—I felt the tears before I heard them in the music.

The violin sang. The hall echoed. And somewhere between the final chord and silence, I swear I heard his voice in my head: Don’t stop the music.

When I lowered the bow, the judges were silent for a heartbeat too long. Then one of them whispered, “Beautiful. Truly.”

I got in. Full scholarship.

Leaving home for the conservatory felt harder than I expected.

Mom helped me pack the violin, the old letters, and a framed photo of her and Henry from college that we’d found in one of his journals.

She smiled through watery eyes. “I think he’d like knowing you’re taking both of us with you.”

The night before I left, we played one last duet in our living room—her on piano, me on violin.

The house filled with warm, golden sound. At one point, she laughed mid-song. “You’ve gotten so good, I can barely keep up.”

“Guess I had a great teacher,” I said.

She stopped playing, looked at me, and whispered, “Both of us did.”

A year later, I came home for spring break. Maple Street looked different—fresh paint, trimmed lawns—but the old rhythms still hummed underneath.

The new family had turned the blue house into something out of a magazine. There were hanging plants on the porch, a new mailbox standing proud.

Mark was mowing the lawn when I pulled up.

“Colton!” he called, waving. “Long time, man!”

“Yeah,” I said, smiling. “Mind if I look around for a bit?”

“Of course not. Go ahead.”

Inside, the layout was the same, just brighter. The living room smelled faintly of lemon polish instead of coffee and cedar.

But when I looked at the corner where Henry’s chair used to sit, I could still see him there—cardigan, soft smile, eyes alive with secrets finally told.

Elise came in carrying a tray of lemonade. “You know,” she said, “sometimes the girls say they hear piano music when they’re falling asleep. We don’t even own one.”

I smiled. “Maybe the house remembers.”

She laughed lightly. “If it does, I hope it keeps playing.”

Before leaving, I slipped an envelope under their doormat. Inside was a thank-you card and a CD recording of April Seventh.

No explanation. Just a note that said, This music belongs here.

That summer, the conservatory invited me to perform April Seventh at the town music festival.

It would be my first public performance since Henry’s funeral.

Mom sat in the front row. When the lights dimmed, I stepped onto the stage, heart pounding.

I looked out and saw her smiling through tears, the necklace with her wedding ring glinting under the white lights.

Then I began to play.

The melody unfolded like a memory being reborn—rising, dipping, carrying everything that had ever been lost and found again.

At the crescendo, I imagined Henry standing at the back of the hall, arms crossed, that proud half-smile on his face.

When the final note faded, the crowd erupted. But all I could hear was the echo of his last words to me:

Your mother named you after me, son.

After the concert, we sat in the car for a long time before driving home. Mom finally spoke.

“There’s something I never told you about the day of the accident,” she said softly. “The last thing Henry said to me before he left for that rehearsal was, ‘Promise me, Judy, no matter what happens, keep the music alive.’”

She looked at me with trembling eyes. “You did that, Colton. You kept his promise for me.”

I reached over, squeezing her hand. “No, Mom. We did.”

She smiled, tears glistening. “Maybe that’s what love really is—keeping the promises someone else couldn’t finish.”

A few weeks later, a letter arrived addressed to The Family of Henry Colton Dawson.

It was from a woman named Margaret Voss—Henry’s sister, living in Vermont.

She wrote that she’d found out about Henry’s death through an old friend. She’d enclosed a photograph of their family estate and a note that said:

I’m sorry for the years of silence. Our parents made decisions none of us should have accepted. If you’re willing, I’d love to meet the nephew I never knew.

Mom looked at me. “Do you want to?”

I nodded. “He didn’t get to have his family back, but maybe we can give him one anyway.”

Margaret Voss turned out to be in her sixties, tall and elegant, with the same blue-gray eyes as Henry. When she opened the door, she gasped softly.

“You have his face,” she whispered. “God, Henry would’ve loved this.”

Over tea, she told us stories about his childhood—how he used to sneak into the attic to play an old violin their grandfather owned. How he’d spend hours teaching himself classical pieces by ear.

When I showed her the violin Henry had given me, she pressed her hands to her mouth. “That’s the same one,” she said. “He restored it himself in college. You have no idea how happy it makes me to see it still being played.”

Before we left, she handed me a small velvet box. Inside was a silver cufflink engraved with the initials H.C.D.

“Your father wore these to every performance,” she said. “He’d want you to have them.”

A year later, I graduated with honors. The conservatory offered me a position teaching young musicians. Mom cried through the entire ceremony, of course.

Afterward, I gave her a small box wrapped in sheet music. Inside was a gold locket shaped like a violin.

When she opened it, she found two photos—one of her and Henry from college, the other of me holding the same violin.

“Now,” I said, smiling, “you can wear both of us close to your heart.”

She hugged me tight, whispering, “You were always my best duet.”

Years later, after I’d moved into my own apartment, I still kept Thursdays sacred.

I’d order a pizza—large pepperoni, extra cheese—tip the delivery driver forty-seven dollars, and tell them, “Tell your mother I’m sorry.”

They’d always blink, confused, and I’d smile.

Because somewhere out there, maybe they’d go home, tell their mom the strange thing I’d said, and a story would start unfolding.

Maybe that’s how love keeps traveling—one ordinary Thursday at a time.

Part Five:

The years passed quietly, the way years do when life has found its rhythm again.

I turned twenty-eight, still teaching at the conservatory, still giving lessons to kids who reminded me of myself—awkward, hopeful, unaware of how much a single act of kindness could change a life.

Mom had retired from Mercy General. She’d taken up gardening, volunteered at the community center, and played piano for the church choir on Sundays. The silver in her hair had grown more pronounced, but her smile—her soft, steady smile—hadn’t aged a day.

Every April 7th, we still played Clair de Lune together.

Every Thursday, I still ordered the same pizza and tipped the driver forty-seven dollars.

Some rituals don’t fade; they become the compass points that keep your heart from drifting.

It was late autumn, the kind of cool evening that smells like woodsmoke and rain. I’d just finished a lesson with a student named Ethan—a quiet twelve-year-old who played like his life depended on it. His mom worked two jobs, his dad was long gone, and the violin was the one thing that steadied him.

After class, he lingered by the door. “Mr. Reeves,” he said shyly, “can I ask you something?”

“Sure.”

“Why do you always have pizza on Thursdays?”

I smiled. “Because it reminds me of where I came from.”

He looked puzzled, so I told him—about the old man who’d tipped me forty-seven dollars, about the apology, the key, the study, the photograph, and the seven words that had rewritten my life.

When I finished, Ethan’s eyes were wide. “That’s like a movie,” he whispered.

“Maybe,” I said. “But real life’s better, because you actually get to keep the people you find.”

He nodded, thoughtful. Then he asked, “Do you think your dad knows you still play?”

I smiled. “Yeah,” I said softly. “I think he never stops listening.”

The Call

Later that night, while I was packing up my violin, my phone buzzed.

It was Tony.

“Colton, you sitting down?” he said, his gravelly voice cutting through the line.

“Uh… yeah. Why?”

“You remember that big chain pizza place out on Route 14—the one putting us out of business?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, they just offered to sponsor a community music fundraiser. Guess who they want to headline it?”

“Who?”

“You,” he said, chuckling. “Apparently one of their district managers heard you play at the festival last year. Said your story ‘represents small-town heart.’”

I laughed. “You’re kidding.”

“Would I kid about free pizza? The gig’s next Thursday night. You in?”

Next Thursday. Of course.

“Yeah, Tony,” I said. “I’m in.”

It was held in the town square under strings of white lights, the kind that make everything look gentler than real life ever does.

The air smelled like garlic and tomato sauce, mixed with autumn leaves and nostalgia. Tables were lined with pizzas from every local place—including Tony’s.

He found me tuning my violin near the stage. “You nervous?”

“Always.”

He grinned. “Good. Means you still care.”

Mom arrived just before the show started, bundled in her favorite gray cardigan—the one Henry used to wear. Around her neck hung the locket I’d given her.

When the announcer called my name, she squeezed my hand. “Play for him,” she whispered.

I stepped up to the microphone.

“Good evening,” I said, the crowd settling into silence. “Some of you know me as the guy from Tony’s who still tips too much. Some of you know me as a music teacher. But before any of that, I was just a kid delivering pizzas to an old man who changed my life.”

A ripple of quiet laughter moved through the audience.

I smiled. “Tonight, I want to play something for everyone who’s ever been separated by time, by mistakes, by memory—and somehow found their way back.”

Then I lifted the violin and began to play April Seventh.

The music unfurled under the canopy of lights—warm, luminous, threaded through with everything we’d ever lost and found.

Somewhere near the back, I saw Mom close her eyes, her hand pressed to her locket.

And for a heartbeat, I could swear I saw him there too—standing behind her, cardigan neat, eyes bright with pride.

Two days later, I found an envelope in my mailbox. No return address. Inside was a single sheet of stationery, the handwriting unfamiliar but careful:

Dear Mr. Reeves,

I was at your performance Thursday night. My husband and I live on Maple Street, in the blue house you used to deliver to. Our daughters adore your music. After the show, they asked who the man in the photo on our piano was. We told them the truth—that he was the man who once lived here, the one who taught us that every house carries the memory of love. Thank you for bringing his story home.

Signed,

Elise and Mark Parker

P.S. The girls are learning violin now. They say the house helps them practice.

I laughed out loud, standing there on my porch, the letter trembling in my hand.

The house remembered, after all.

That Sunday, I visited Mom. She’d redecorated her living room since I’d left for college—new curtains, fresh paint—but the piano still sat in the same corner.

“Play something for me,” she said, smiling.

I set down the violin case. “Only if you play too.”

We launched into a piece Henry had loved—Moon River. Halfway through, she looked up at me, eyes shining.

“You know,” she said softly, “I still dream about that night sometimes. The first time he remembered me. It always starts with him saying my name—‘Judy’—and ends with those seven words.”

I nodded. “Your mother named you after me, son.”

She smiled. “That one sentence gave me everything back.”

The final notes faded, leaving only the hum of the strings and the sound of rain tapping against the window.

A year later, Ethan—the shy kid from my class—entered a regional music competition. He’d written his own piece, inspired by April Seventh.

He called it The Thursday Song.

When he played it at the recital, he wore a borrowed tie, hands shaking, but his bow never faltered.

After the performance, I asked what the song meant to him.

“It’s about how small things matter,” he said. “Like how one person can say something weird—like ‘Tell your mother I’m sorry’—and it ends up changing everything.”

I couldn’t speak for a moment. I just nodded and said, “You get it.”

Years later—after Mom passed peacefully in her sleep, after the conservatory named a scholarship in her honor, after I’d become “Professor Reeves” to a new generation of hopeful musicians—I found myself driving down Maple Street again.

It was evening, close to sunset. The blue house still stood, freshly painted now, porch light glowing softly.

I pulled over, just to sit there for a minute.

The new family was hosting a backyard birthday party. Children’s laughter spilled into the street, and someone was playing a tune on a portable speaker—an instrumental version of Clair de Lune.

I smiled, shaking my head at the sheer poetry of it.

Then I noticed a pizza delivery car pulling up. A young driver stepped out, maybe nineteen, holding a box that looked far too big for one person.

The door opened. Elise—the homeowner—smiled, handing him cash.

Something made me roll down my window. The driver’s voice carried faintly through the air: “Uh, ma’am, you gave me too much. This is forty-seven dollars extra.”

Elise smiled. “It’s correct.”

I froze.

“Tell your mother I’m sorry,” she added softly.

The kid blinked, confused. “Uh… okay, sure thing.”

As he turned back toward his car, his eyes met mine for the briefest second. He looked at me the same way I must’ve once looked at Henry—half curious, half unsettled, like some invisible hand had just nudged the gears of fate into motion.

He drove off, headlights cutting through the dusk.

I sat there for a long moment, the weight of time settling gently around me.

Then I whispered into the quiet, “Good job, Dad. The story keeps going.”

The next spring, I performed my final recital before retiring from the conservatory. The hall was packed with students, friends, and townspeople who’d followed our story for years.

Before I played, I told them the short version:

“Once upon a time, I was a broke college kid delivering pizza. An old man tipped me forty-seven dollars every Thursday and told me to tell my mother he was sorry. It took me six months—and a lifetime—to understand why. His name was Henry Dawson. He was my father.”

The crowd was silent.

I smiled. “Everything I’ve ever played since then has been a thank-you note.”

Then I lifted the violin—Henry’s violin—and began April Seventh one final time.

The music swelled, filling the hall, reaching up into the rafters and maybe, just maybe, beyond them.

I imagined him there in the front row, cardigan neat, smiling that quiet smile. Mom beside him, her hand resting on his.

And when the final note hung in the air, I let it fade slowly—until the silence became its own kind of song.

Afterward, as the audience filed out, I stayed on stage alone for a while. The white lights glowed softly overhead, like a benediction.

I placed the violin back in its case, running my hand over the smooth wood one last time. “You did good, old friend,” I murmured.

Outside, the night was cool and full of stars. I walked to my car, started the engine, and for no reason other than habit, drove toward Maple Street.

When I reached the end, I parked in front of the blue house. The porch light was still on, like always.

I didn’t get out. I didn’t need to.

The music, the memories, the forgiveness—they all lived here now, woven into the very wood of that house, into the air of that street, into every Thursday night that would ever come after.

And somewhere, maybe in the spaces between heartbeats and history, I could almost hear it again:

“Tell your mother I’m sorry.”

Then, softer, as if the wind itself carried the words—

“Your mother named you after me, son.”

That was the last delivery.

But it was never really about pizza.

It was about love—waiting, remembering, forgiving—and how sometimes the universe uses the smallest things to deliver us home.

THE END

News

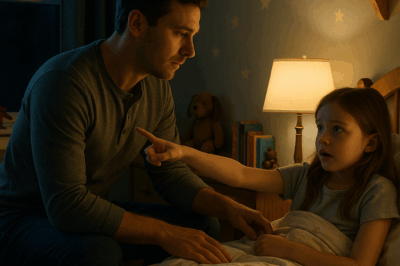

CH2 – WHILE BABYSITTING MY NEIGHBOR’S 2-YEAR-OLD, MY DAUGHTER CALLED FROM HER ROOM. ‘DAD…’

Part 1: I’d always believed our street was safe. The kind of place where porch lights glowed warm and steady,…

CH2 – THE CEO CALLED AN ALL-HANDS MEETING AND DEMANDED: “APOLOGIZE TO MY SON NOW, OR CLEAN OUT YOUR DESK.”…

Part I They say every company has a ghost. At Lexicon Systems, that ghost was me. Not the kind that…

CH2 – My Gay Best Friend and My Husband Fell in Love. I’m Losing My Mind…

Part 1: If you had asked me a week ago what the worst thing that could ever happen to me…

CH2 – MY 7-YEAR-OLD ASKED, “DAD, WHO’S THAT MAN WHO WATCHES ME SLEEP?” “NOBODY WATCHES YOU, HONEY…”

Part I You never forget the way your child looks at you when they ask a question that doesn’t belong…

CH2 – I Got On The Wrong Train By Mistake. A Stranger Said: “You’re Exactly On Time.”…

Part 1: It was the kind of cold November morning that made the whole city feel like it had given…

CH2 – “I Inherited a Rusty Storage Unit from My Grandpa — a Retired Navy SEAL. But When I Opened It…”

Part I The last time my father spoke my name in public, he said it like a disappointment he couldn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load