Part One

At 3:11 in the afternoon, the cul-de-sac WhatsApp chat lit up like a Christmas tree on fire.

Someone had posted a video of the HOA golf cart skidding sideways down Alderrest Drive, mud spraying in all directions, the board members screaming like a community theater version of Titanic.

Two of them were holding patio umbrellas — open — as if they’d help.

Behind them, the hillside peeled away like fondant sliding off a cake left too long in the sun.

And leading the parade of panic, in her pink windbreaker and pearls, was Mara Yates, President of Ridge View Overlook Homeowners Association, shrieking at the top of her lungs, “It’s only a minor slippage!”

If you’d seen the footage without context, you might’ve thought it was a comedy sketch.

But I was the one who’d written six separate reports warning that this would happen.

And the road that was now surfing its way into the valley below?

That was the one I lived on.

My name is Caleb Royce, and I moved to Alderrest Drive for three simple reasons: the quiet, the birds, and the way the morning fog sits in the valley like a sleeping cat.

After fifteen years working as a geotechnical engineer, I wanted a place where the ground didn’t move unless I told it to.

Irony has a sense of humor I don’t appreciate.

I’m the kind of man who prefers porch coffee over gossip, diagrams over drama, and data over denial. Unfortunately, those values don’t play well in an HOA ruled by a woman who believes physics is a matter of personal confidence.

Mara Yates had been HOA president for seven consecutive years — a tenure she liked to describe as “a commitment to maintaining excellence” and everyone else called “a reign of terror with better landscaping.”

She was fifty-three, wore her blonde highlights like battle armor, and wielded her clipboard as if it were Excalibur.

Her nails were manicured into sharp, weapon-grade French tips that she used to point, accuse, and occasionally tap menacingly on the conference table.

Every meeting followed the same format:

Mara opens with a quote about positivity and unity.

Someone raises a legitimate issue.

Mara interprets it as a personal attack.

The issue is dismissed as “non-aligned with community morale.”

Someone gets fined.

She had fined a neighbor for planting “unapproved perennials,” another for hosting an “unregistered garage sale,” and me — repeatedly — for trying to keep the street from collapsing.

It started innocently enough.

A rainy February afternoon, a few hairline cracks in the asphalt near my driveway.

Most people wouldn’t notice, but I see soil movement the way a doctor sees symptoms.

The slope behind Alderrest was steep — 35°, maybe more — with an old subdrain system installed sometime in the early 2000s.

It hadn’t been maintained in years, and the community’s “decorative retaining wall” was built for looks, not load.

To the untrained eye, it was charming — stacked river rock with lavender planters.

To my eye, it was a death wish with curb appeal.

I wrote a five-page report with diagrams, photos, and recommendations:

Jet the subdrains.

Regrade the slope.

Install proper retaining systems before the next winter storm.

I emailed it to the HOA with the subject line:

“URGENT: Hillside Stability and Imminent Risk Assessment.”

Mara replied five hours later:

“Dear Mr. Royce,

Thank you for your enthusiasm regarding community maintenance.

However, please refrain from distributing alarming material that could negatively affect property values.

The board had a consultant review the slope in 2008 and found it perfectly stable.

Best,

Mara.”

I’d just been told by a woman with a degree in marketing that geology was subject to majority vote.

When the next rainfall hit, I taped off the slope behind my fence and laid sandbags along the runoff channels.

It wasn’t pretty, but it worked.

A week later, I got a letter.

“Violation: Unsightly Materials Visible from Common Area. Fine: $250.”

I called Mara.

She said, “Caleb, we can’t have a panic aesthetic. It spreads fear.”

“I’m preventing erosion, not hosting a panic parade,” I said.

“Still, the bags clash with the natural palette. Maybe you can replace them with decorative river rock?”

River rock.

The same kind of rock that water loves to slide over like a slip ’n’ slide.

I refused.

She doubled the fine for “noncompliance with aesthetic directives.”

Data vs. Denial

I decided to fight fire with science.

I installed a tilt sensor and a ground moisture monitor halfway down the slope.

Every week, I uploaded graphs to the community portal showing the incline angle and water saturation levels.

The data was clear: the hillside was slowly shifting.

Mara responded by circulating a glossy flyer at the next HOA meeting with the headline:

“Don’t Let Fearmongers Devalue Our Homes!”

The flyer had a photo of the hillside on a sunny day with a rainbow overlay and, in smaller print:

“Our hillside is stable. We had a consultant look at it in 2008.”

She even started calling me Doomsday Royce.

I didn’t mind.

I’d been called worse by county lawyers.

The final straw came in May, when her “Beautification Task Force” decided to pressure wash the moss off the communal stairwell.

I’d explicitly warned them that the runoff would drain into the same clogged subdrain system that was already on the brink of failure.

They ignored me.

They sprayed everything — stairs, railings, each other — using industrial-grade pressure washers.

They washed the moss right into the drain I’d marked with orange paint.

A week later, my tilt sensor recorded a 2° movement.

That might not sound like much, but in my field, it’s a whisper of disaster.

I emailed Mara again.

She fined me $300 for “alarmist communication tone.”

By November, the soil was waterlogged.

Hairline cracks had deepened into jagged seams.

The sound of trickling water echoed beneath the pavement like a pulse.

Then came the atmospheric river — a storm system so relentless it felt like the sky itself was melting.

I stayed up that night watching my monitor ping.

2°, then 3.5°, then 5°.

At 5°, the soil beneath Alderrest wasn’t a slope anymore. It was a conveyor belt.

I called the county geohazards unit, filed an emergency report, and then — because I’m apparently an optimist — called Mara one last time.

“Mara, the slope’s moving. I’m telling you as a professional, close the road right now.”

Her voice was steady, almost cheerful.

“Caleb, we can’t just panic every time it rains. People are already calling me worried about your negativity. I think we need to set an example of calm.”

“What does that even mean?” I asked.

“It means we’re having a Positivity Walk.”

I blinked. “You’re—what?”

“A community walk to demonstrate confidence in our infrastructure. We’ll film it for the Facebook page.”

I was speechless.

She added, “You’re welcome to join us if you promise not to bring your orange cones.”

I hung up before I said something unprintable.

Alderrest at 3:11 p.m.

The next afternoon, I stood at the top of the hill with my camera running, documenting the cracks widening near the curb.

Below me, the HOA golf cart rolled into view.

It was decorated with balloons.

Mara stood in the passenger seat, wearing a sash that said Positivity Walk Lead, waving like a parade queen.

Behind her, two board members clung to patio umbrellas as if this were going to be a whimsical jaunt through a storm instead of a descent into geological chaos.

They drove straight past my barricade.

Past the ROAD CLOSED sign I’d zip-tied to sawhorses.

Past the orange cone marking a sinkhole that had already swallowed part of the gutter.

“Cones are a suggestion, not a rule!” Mara shouted, and I swear I have it on video.

Then the hill moved.

It began as a vibration, deep and low, like the earth clearing its throat.

The pavement shuddered.

The white paint of the golf cart’s tires blurred as it fishtailed.

And then — all at once — the hillside let go.

A section of Alderrest Drive, maybe fifty feet across, dropped six feet in a single, wet lurch.

The golf cart lurched sideways, sliding on liquefied clay.

Mud geysered from the broken curb line.

The hydrangea garden at the bottom vanished under a brown wave.

Mara screamed — not words, just sound.

Two board members tried to jump out and immediately slipped, surfing down in a tangle of umbrella fabric and business casual khakis.

The HOA mailbox cluster tore loose and rode the wave like a toboggan straight into Mara’s yard.

It was the single most satisfying act of poetic justice I’ve ever witnessed.

By the time emergency sirens wailed through the valley, the cul-de-sac chat was a wall of panicked texts.

“Is everyone okay?”

“My fence is gone!”

“Someone check on Mara!”

I just sat on my porch, soaked in rain, coffee mug in hand, watching gravity prove my point in real time.

Nobody died.

Which, considering the stupidity involved, was a miracle.

We had a few sprained ankles, one dislocated shoulder, and several shattered egos.

But the real damage was only beginning.

Because the county had seen the emails.

The fines.

The warnings ignored.

And they weren’t just angry — they were taking notes.

When the emergency crew arrived, one of the geotechnical engineers stepping out of the truck was Dr. Russell, the man I’d interned for fifteen years ago.

He took one look at the slope, at the burlap “safety garlands” still fluttering in the wind, and asked out loud,

“Who the hell decorated this hazard?”

I raised my hand. “The HOA president.”

He nodded grimly. “Then I hope she’s ready for a geology lesson she’ll never forget.”

Part Two

When I bought the cedar A-frame on Alderrest Drive, I thought I was buying serenity.

It sat at the end of the ridge where fog rolled in every morning, softening everything until even the power lines looked romantic.

I’d pictured early coffee on the deck, the smell of wet pine, the peace of hearing only birds and the occasional neighbor’s dog.

What I hadn’t pictured was being fined three separate times for unsightly caution tape.

I made the rookie mistake of thinking reason could exist inside a homeowner’s association.

The first time I showed up to a Ridge View Overlook board meeting, I brought slides.

Actual slides. Soil cross sections, moisture charts, a short video explaining what happens when subsurface drains fail.

The meeting was held in Mara’s living room because, as she said, “it promotes a sense of community.”

In practice it meant she could sit in her high-back chair beneath a framed motivational quote that read Progress Through Positivity and glare at us over her glass of Chardonnay.

I had just pulled up the first graph when she interrupted.

“Caleb, before you go on, let me ask—how many of your neighbors have complained about the hillside moving?”

“None yet,” I said. “Because it hasn’t collapsed yet. That’s the point of prevention.”

She smiled. “Exactly! So maybe we can keep this brief. We don’t want to end on a negative note.”

I kept going anyway. I showed the boring logs I’d drilled myself, the groundwater readings, the slope angle.

I explained what “factor of safety” meant — basically, how close a hillside was to deciding gravity’s had enough.

Mara tapped her pen against her wineglass.

“So, in your professional opinion, this ‘factor of safety’ thing is… low?”

“Yes. Critically.”

She nodded slowly, like a teacher humoring a particularly imaginative student.

“Well, I appreciate your passion, but the board’s budget is already allocated. We’ve committed to upgrading the pergolas by the pool this quarter.”

“The pergolas won’t matter if they slide into the canyon,” I said.

A few people laughed nervously. Mara didn’t.

“Let’s all try to keep a constructive tone. Fear doesn’t build community.”

When I sat down, the agenda moved on to “Holiday Light Uniformity Standards.”

That was my first lesson: data doesn’t stand a chance against décor.

Two weeks later, heavy rain started up again.

The storm drains gurgled like they were choking.

A section of curb on the downslope side began to separate from the asphalt — just half an inch, but enough to make my stomach knot.

I emailed the HOA another report: photos, measurements, timestamps.

Mara responded the next morning:

“Caleb, the board has reviewed your concerns and concluded that you are over-monitoring.

Please refrain from creating unnecessary panic in the neighborhood.”

Over-monitoring.

That’s what she called it when I noticed the ground was literally moving.

After that, the fines arrived like junk mail.

$250 for “unsightly caution tape.”

$300 for “negative community tone.”

$500 for “installation of non-approved safety devices.”

Each notice came in an envelope embossed with the HOA logo — a stylized mountain that, in hindsight, looked disturbingly like it was sliding downhill.

When I replaced the sandbags she ordered me to remove, she cited me for “defiance.”

I asked her in writing if “defiance” was an actual clause in the bylaws.

She replied with a smiley-face emoji and a line that said, “Let’s all try to stay positive!”

If passive aggression were a renewable energy source, Ridge View Overlook could’ve powered the entire state.

By early spring, I’d run out of polite words.

The slope behind my house was oozing water like a sponge.

I fenced off the area with orange safety netting and put up a sign that read ACTIVE SLIDE AREA—DO NOT ENTER.

Mara showed up that afternoon with two members of her Beautification Task Force, wielding pruning shears like bayonets.

“Caleb,” she said, “this is a visual blight.”

“It’s a warning,” I said. “And it’s keeping people off unstable ground.”

“But it’s orange. Nothing else in the community is orange.”

“That’s because orange gets people’s attention.”

She smiled the way people do right before they call the cops.

“I’m replacing it with something that fits our palette.”

The next morning my safety fencing was gone.

In its place, she’d strung burlap ribbons threaded with sprigs of lavender.

It looked like a wedding aisle for people with a death wish.

I took photos for documentation.

By evening she’d fined me again for “unauthorized signage.”

For a few blessed months, the weather stayed dry.

The grass browned. The cracks in the pavement stopped widening.

Even I started to relax, convincing myself maybe the slope would hold another season.

But every time I walked past the decorative retaining wall, I heard it — a faint hollow sound, like tapping on a drum.

The soil behind it had separated. The wall was performing the structural equivalent of jazz hands.

When I mentioned it at the July board meeting, Mara said, “We’ll revisit the issue when it rains again.”

I looked around the room. Nobody met my eyes.

Everyone wanted peace, even if it meant pretending physics took vacations.

By October, drizzle returned. The first storm hit hard.

Water pooled across Alderrest Drive where the pavement had sunk.

I measured the depression: three inches at center.

I sent an email titled “Emergency Maintenance Needed.”

This time, Mara didn’t reply at all.

Instead, two days later, she dropped a glossy flyer in every mailbox.

Across the top in cheerful blue letters:

“Slope Serenity — Keeping Ridge View Beautiful and Strong!”

Below was a photo of the hillside bathed in sunshine with a cartoon rainbow stretched across it.

The caption read:

“Don’t let fearmongers ruin our view. Ridge View’s hillsides were certified stable by a consultant in 2008.”

She had underlined “2008” like it was a sacred date.

I decided to take human opinion out of it entirely.

I installed a tilt sensor halfway down the slope — a compact device that measures ground movement in degrees.

Then I wired it to my phone.

Every Sunday I posted the readings to the community portal.

At first, people ignored them.

Then they started commenting things like, “Thanks, Caleb! So interesting!”

Then Mara deleted the posts for “causing unnecessary anxiety.”

I reposted them.

She locked my account.

So I printed them out and taped them to the community bulletin board instead.

The next morning they were gone, replaced by a flyer advertising the upcoming “Positivity Potluck.”

December came in gray and heavy.

Every storm rolled straight in from the Pacific like a freight train.

Rain hammered the roofs day and night.

My tilt sensor went from a stable 0° to 1.7° in forty-eight hours.

Then 2.3°. Then 3°.

At 3°, the soil wasn’t resting anymore — it was creeping.

I emailed Mara again, copying the entire board and the county’s geohazards unit.

“Immediate action required. The subdrain system is nonfunctional. The slope is at critical saturation.

Recommend road closure and evacuation of downhill homes.”

Mara’s response came twenty minutes later:

“Caleb, thank you for your input. We can’t keep alarming residents every time it rains.

Please allow the board to handle this internally.”

She attached a photo of herself holding an umbrella with the caption “Staying positive!”

I forwarded the whole chain to the county office and made sure to timestamp it.

Something in me knew this was the point of no return.

The next day, Mara announced her plan.

An email blast went to every homeowner:

Subject: Community Confidence Walk — Saturday 3 p.m.

Dear neighbors,

Let’s show Ridge View we believe in our infrastructure!

Join the HOA board for a joyful ride down Alderrest Drive in our official golf cart to demonstrate that our community is safe, strong, and positive.Please wear cheerful colors. Rain gear optional!

–Mara Yates, HOA President

I reread it three times, certain it had to be parody.

It wasn’t.

I called her.

“Mara, you can’t drive down that road. It’s unsafe.”

“Caleb, we can’t give in to hysteria.”

“This isn’t hysteria. It’s hydrology.”

She laughed lightly. “I appreciate your passion.”

“Mara, if you take that golf cart down there, the road could give way beneath you.”

“Oh, Caleb,” she said, almost pitying, “you really should attend one of our mindfulness workshops.”

By Saturday morning, the rain hadn’t stopped for three straight days.

Runoff poured from the hillside like veins opening.

I set up barricades: sawhorses, cones, a bright red sign that read ROAD CLOSED – ACTIVE SLIDE.

I sent one final text to Mara.

“Do not drive on Alderrest. The slope is unstable. I’m not kidding.”

She left me on read.

At 2:45 p.m., I watched from my porch as she gathered the board at the top of the street, all smiles, glittery sash reading Positivity Walk Lead.

At exactly 3:00, the golf cart began its descent.

At 3:11, Alderrest Drive collapsed.

When the county trucks arrived hours later, sirens wailing, one of the engineers — my old mentor, Dr. Russell — stepped out, looked at the mess, and muttered,

“Jesus Christ, it’s a landslide with gift wrapping.”

I could’ve told him that gift wrapping was mandatory here.

Part Four

If the landslide had been the explosion, the hearing was the slow, methodical cleanup — not of mud, but of egos.

Three weeks after Alderrest Drive tried to relocate itself downhill, every folding chair in the county commission auditorium was filled.

Neighbors who hadn’t spoken in years sat shoulder to shoulder, clutching Styrofoam coffee cups like life rafts.

Everyone wanted to see how Mara Yates would talk her way out of this one.

The county had bundled everything together: emergency abatement order, violation of public safety codes, and interference with a government hazard notice.

They even listed my email chain as Exhibit A.

The moment I walked in, Mara looked away.

She was in her full boardroom armor — navy blazer, pearls, perfect hair.

Her lawyer, a narrow-shouldered man named Dunlap, had the haunted expression of someone who’d realized too late that his client was both wrong and loud.

At the other table sat the county’s team: engineers, a geologist, a public safety officer, and a city attorney with the calm smile of a man about to enjoy himself.

I sat behind them with Tina, who had the video cued up on her laptop.

“Still can’t believe she drove into it,” Tina whispered.

“Believe it,” I said. “I’ve got the footage to prove it.”

Dunlap stood first, buttoning his suit jacket like a magician about to perform an illusion.

“Your Honor,” he began, “this was a natural disaster — an act of God exacerbated by historic rainfall. The homeowners association acted in good faith, relying on prior reports certifying the hillside as stable.”

The judge, a silver-haired man named Harold Miles, lifted an eyebrow.

“Prior reports?”

“Yes, Your Honor. From 2008.”

The courtroom murmured.

Miles leaned back. “Counselor, I was still paying my student loans in 2008. You want to rest your case on a document older than my dog?”

Dunlap stammered something about precedent.

The judge motioned for the county to proceed.

Exhibit A

The county attorney, Ms. Ortega, approached the projector screen and clicked through a series of slides.

Each one was an email from me, time-stamped, polite, and increasingly desperate.

“March 8th — evidence of ground movement behind Alderrest Drive.”

“April 2nd — subdrain system clogged; recommend jetting immediately.”

“June 15th — slope saturation high; recommend retaining wall reinforcement.”

“October 28th — imminent risk of failure; close the road.”

Every email was signed Caleb Royce, P.E.

Ms. Ortega turned to the judge. “These were sent directly to the Ridge View Overlook HOA board and its president, Ms. Yates. No action was taken. In fact, the board issued fines against Mr. Royce for what they termed ‘negative community tone.’”

The audience laughed softly.

Judge Miles smirked. “Negative tone? That’s a new one.”

“Your Honor,” Ortega continued, “not only were warnings ignored, but safety measures were removed—sandbags replaced with decorative rocks, safety fencing replaced with burlap ribbons. All to maintain aesthetic consistency.”

She clicked to the next slide: a photo of the lavender-studded burlap strung across a crumbling slope.

Someone in the audience gasped.

Someone else muttered, “That’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever seen.”

Mara’s jaw tightened.

Exhibit B

Tina stepped up like she’d been waiting her whole life for this.

She connected her laptop to the projector and hit play.

The screen filled with rain, shouts, and the now-infamous image of the HOA golf cart skidding sideways down Alderrest Drive.

Mara’s voice shrieked over the speakers: “It’s only a minor slippage!”

Every laugh in the room was involuntary.

Even the bailiff covered a smile.

Then came the part where she physically moved my traffic cone.

On screen, she said, “Cones are a suggestion, not a rule!”

The judge paused the video and looked over his glasses.

“Ms. Yates, did you say that?”

She lifted her chin. “I believe I was attempting humor in a stressful situation.”

Miles deadpanned, “Well, your timing was tragic.”

Exhibit C

Dunlap tried to recover by calling their so-called “expert.”

A thin man in a wrinkled suit shuffled to the stand.

He introduced himself as “Consultant Alan Frey.”

Ms. Ortega approached.

“Mr. Frey, you authored the report Ms. Yates relied upon?”

“Yes. The 2008 slope stability assessment.”

“Could you remind the court where that assessment was conducted?”

He cleared his throat. “Uh… the Eastwood Terrace subdivision.”

The room erupted in whispers.

Ortega frowned. “Eastwood Terrace? That’s five miles away.”

“Correct. Similar topography, though.”

Judge Miles blinked. “You mean to tell me this report wasn’t even for Alderrest Drive?”

Frey nodded meekly. “It was a comparable case study.”

Ortega smiled. “Comparable in that both locations experience gravity?”

The audience laughed outright.

The judge banged his gavel once but couldn’t hide his grin.

Exhibit D

Next came the county’s geotechnical engineer — Dr. Russell himself.

He set a model on the table: a clear plastic box filled with layered soil and a miniature retaining wall.

Beside it sat a pitcher of water.

“This,” he said, gesturing to the model, “is Alderrest Drive.”

He poured water over it. Slowly, the soil turned dark and heavy.

“The more water, the less shear strength. Eventually—”

He tipped the box slightly. The soil slumped forward, the miniature wall tipping over.

“—it moves downhill. That’s what gravity does.”

Mara’s lawyer objected. “Your Honor, this demonstration is prejudicial.”

Miles stared at him. “Are you objecting to physics?”

Laughter rippled again.

The objection was overruled.

Russell turned toward the defense table.

“When you decorate a hazard instead of reinforcing it, you aren’t preventing failure. You’re holding a garden party for one.”

That line made the evening news.

When it was Dunlap’s turn to cross-examine me, he tried a new tactic — attack the messenger.

“Mr. Royce, you’re a resident of Ridge View Overlook, correct?”

“Yes.”

“And you’ve had disagreements with the HOA board before this incident?”

“I’ve disagreed with their disregard for safety, yes.”

He paced a little. “Isn’t it true you used phrases like ‘inevitable collapse’ and ‘critical hazard zone’? Don’t you think that language was alarmist?”

“Not when it was accurate.”

“So you admit your tone could have caused community panic?”

I leaned forward. “If panic had gotten them off that road, maybe we wouldn’t be here.”

The courtroom murmured approval.

The judge didn’t even hide his smirk.

When they called Mara, she glided up like she was stepping into a pageant, not a deposition.

She swore the oath with one hand on the Bible, the other clutching her clipboard.

“Ms. Yates,” Ortega began, “why did you proceed with the so-called Positivity Walk after receiving multiple warnings?”

Mara smiled tightly. “We wanted to show calm leadership. People were scared. Property values were at stake.”

“And you thought driving a golf cart over a collapsing road would help property values?”

She bristled. “Optics matter. We wanted to project confidence.”

“Confidence in what, exactly?”

Mara hesitated. “In our hillside’s stability.”

Ortega held up a photo of the aftermath — the slope torn open, mud everywhere.

“How confident do you feel about it now?”

Mara’s lips trembled. “We couldn’t have known.”

Ortega flipped to one of my emails. “Mr. Royce told you exactly what would happen.”

Silence.

Finally, Mara said softly, “We thought he was exaggerating.”

The judge leaned forward. “Ms. Yates, gravity is not known for exaggeration.”

It took less than two hours for the court to rule.

The HOA was found guilty of negligence and obstruction of emergency safety measures.

The association’s board was dissolved, and an independent receiver was appointed to oversee all maintenance and repairs.

Then came the personal judgment.

The county assessed full liability for damages against Mara Yates herself — over $842,000 in emergency stabilization costs, plus fines, plus restitution to affected homeowners.

Her lawyer tried to appeal for leniency.

The judge shut him down.

“Ms. Yates, leadership means taking responsibility, not selfies during disasters. This court sentences you to 180 hours of community service with the county flood mitigation department. Maybe there you’ll learn to appreciate caution tape.”

The gavel came down with a crack that echoed like thunder.

The local paper ran the headline:

“HOA President Blames Positivity; Gravity Disagrees.”

The video went viral — a mix of slapstick and schadenfreude.

Reporters camped outside Ridge View for days.

I started getting emails from engineers across the country: “You’re the guy from the golf cart landslide, right?”

Tina put her footage online and donated the ad revenue to the county disaster relief fund.

Last I checked, it had half a million views.

Mara, for her part, vanished for a while.

Her house went up for sale within the month.

The new owners, bless them, installed a proper retaining wall before moving in.

The receiver took over HOA operations.

For the first time, things actually got done — drains cleared, soil tested, roads repaired with proper grading.

Nobody talked about positivity anymore. We talked about stability.

At the next neighborhood gathering, someone handed me a mug that said I TOLD YOU SO in big orange letters.

I laughed harder than I had in years.

Sometimes justice doesn’t need to shout.

Sometimes it just lets the hill speak for you.

Part Five

Three months after the landslide, Alderrest Drive no longer looked like a disaster zone.

The county contractors had carved away the broken asphalt and rebuilt the slope with layers of soil nails and concrete retaining systems.

From my porch, I could see new drainage pipes gleaming silver in the sunlight, slotted neatly into the hillside like stitches on a healed wound.

For the first time in years, I could sit with my morning coffee without feeling the ground hum beneath me.

Peace had returned—real peace, not the kind that came from glittery flyers promising “community serenity.”

The irony wasn’t lost on anyone.

The same neighbors who’d avoided me for months were now calling me “the guy who saved the block.”

If I had a nickel for every “you were right,” I could’ve paid Mara’s legal fees myself.

The independent receiver took over HOA operations and treated them like a construction site instead of a country club.

Gone were the floral letterheads, the pink clipboards, and the mandatory positivity workshops.

The new board meetings had a different soundtrack: printers, calculators, and the blessed silence of professionalism.

The first order of business was reinstating my “negative tone” reports as official reference documents.

They even framed one of my emails—the one titled “Imminent Risk of Failure”—and hung it in the new clubhouse with a plaque that read:

“LISTEN TO YOUR ENGINEERS.”

Tina got elected to the new board.

Her first motion was to implement a “No Fine Without Cause” rule.

Her second motion was to ban glitter from all official signage.

“Glitter’s a gateway to denial,” she said, and no one argued.

Mara started her community service the following month.

I didn’t go looking for her, but word travels fast in Ridge View.

She was assigned to the County Flood Mitigation Depot, the very place that distributed the orange sandbags she’d once called “visual pollution.”

They made her wear a bright yellow vest that said VOLUNTEER – PUBLIC SAFETY across the back.

Every Saturday, she stood under a canopy handing out sandbags to residents preparing for storm season.

I drove by one afternoon on my way to a site inspection.

She was stacking bags with surprising efficiency, hair tied back, nails unpainted for once.

When she saw me in the driver’s seat, our eyes met for half a second.

She didn’t look angry.

She looked tired—like someone who’d finally realized the world doesn’t bend to optimism.

I gave her a small nod. She didn’t return it, but I saw the faintest twitch of acknowledgment before she turned back to her work.

Maybe that was her version of an apology.

Or maybe gravity had finally done the explaining for me.

Winter came again.

The rain returned, softer this time.

It drummed on the new drainage grates, ran neatly down the reinforced channels, and vanished into the storm system like it was supposed to.

The first big storm of the season hit on a Tuesday night.

I sat by the window, watching the slope hold firm.

No slides. No cracks. No late-night emergency alerts.

Just water moving exactly where it should.

I raised my mug to it.

To science, to stubbornness, to orange cones and ugly sandbags—the unglamorous heroes of every hillside.

The neighborhood came alive again once the fear lifted.

We started having weekend barbecues, this time with actual safety clearances.

Kids rode bikes down the upper section of Alderrest, the one that still existed.

Even the valley view looked cleaner somehow, as if the storm had rinsed away all the pretense along with the mud.

At one gathering, Greg Walters—the treasurer who’d been on the golf cart—came up to me holding a beer.

He’d fractured his wrist in the slide but kept his sense of humor.

“Caleb,” he said, “I think we owe you a plaque.”

“You owe me a functioning drainage system,” I said.

He laughed. “We’ve got both now.”

Patty Lin, the Beautification Chair, had become unexpectedly humble too.

She’d started volunteering for the new safety subcommittee and was learning how to read soil stability reports.

“Better late than never,” she told me one afternoon, holding a clipboard full of slope angle diagrams.

“I still like flowers,” she said, “but maybe they belong in pots, not retaining walls.”

Progress comes in strange packages.

A few weeks later, a local news station called.

They were doing a segment called “When Homeowners Know Best” about ordinary residents who’d stood up to bad management.

The reporter asked, “What did it feel like, watching them drive right into something you predicted?”

I thought about the golf cart, the umbrellas, the streamers.

Then about the mud, the noise, the relief when no one died.

“Like watching a slow-motion science experiment with people you warned not to light the fuse,” I said.

She laughed awkwardly. “And how did it feel when you were proven right?”

“Expensive,” I said. “Being right usually is.”

They aired the interview that weekend.

My phone buzzed with messages from old colleagues:

“That line—‘Being right is expensive’—chef’s kiss.”

If there’s ever a quote for my gravestone, it’ll be that one.

By spring, the hill looked better than it ever had.

Where there’d once been burlap ribbons and lavender sprigs, there was now steel-reinforced concrete, drainage trenches, and proper grading.

It wasn’t pretty, but it was safe.

The county engineers even planted native grasses for erosion control—actual ground cover instead of Mara’s “aesthetic mulch.”

When the sun hit the new retaining wall, it gleamed faintly silver, like a monument to common sense.

Sometimes I’d stand there and think about everything that happened—the fines, the arguments, the laughter in court.

It still amazed me how far people will go to avoid an ugly truth.

They’ll build fences around it, decorate it with flowers, call it negative energy.

But the truth doesn’t need anyone’s approval.

It just waits.

And when it moves, you either get out of the way or get buried.

Life settled into something normal again.

I went back to work consulting on hillside stabilization projects.

Clients started requesting me specifically—apparently “the engineer who predicted the HOA landslide” sounded credible.

Tina and I started having coffee every Sunday.

She’d tease me that I should write a book.

“Call it The Slope Always Wins,” she said once.

I laughed. “Too on the nose.”

But I did start writing—notes, reflections, diagrams—because maybe she was right.

Not about the title, but about the lesson.

The world’s full of Maras, people who think reality can be negotiated if you smile hard enough.

And it’s full of people like me, too: the ones who keep raising flags no one wants to see.

Both kinds are necessary, I guess.

But only one of them keeps the ground from moving.

In late February, another atmospheric river swept across California.

The emergency alerts lit up my phone, but I didn’t panic this time.

The slope held.

Every drain ran clear.

The lights stayed on.

Around midnight, I walked outside to check the sensors.

Rain hissed against the new concrete.

The hillside stood solid beneath the downpour—quiet, unmoving, honest.

Across the valley, lightning flashed, illuminating the neighborhood below.

For a moment, I thought about Mara—somewhere out there, maybe stacking sandbags, handing them out to strangers.

Maybe she’d learned something.

Maybe she hadn’t.

Either way, the lesson was written into the ground now.

I raised my mug to the rain and whispered to the night,

“Here’s to ugly safety and inconvenient truth.”

Every field has its own laws.

In mine, the first one is simple: Everything eventually moves downhill.

The second: The higher you build your ego, the longer the fall.

When people ask what really caused the Alderrest Slide, I give them the technical answer first—clogged subdrains, saturated clay, loss of shear strength.

But if they ask what really caused it, I tell them the truth:

It wasn’t rain.

It wasn’t soil.

It was pride.

Pride that thought appearance could hold back gravity.

Pride that fined people for being honest.

Pride that mistook confidence for competence.

And in the end, gravity doesn’t negotiate with pride.

It just waits for the perfect moment—and then, inevitably, it wins.

On calm mornings now, when fog curls through the valley like a sleeping cat, I sit on my porch with coffee and listen to nothing but birds and wind.

No arguments, no fines, no false optimism—just the quiet hum of a world that finally learned its lesson the hard way.

Because I warned them about the landslide.

They drove in anyway.

And when they ran for their lives, the only thing that stayed standing

was the truth.

THE END

News

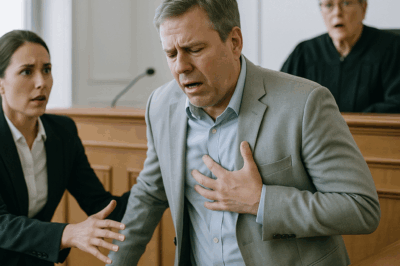

CH2 – Judge Did Not Believe My Wife Abused Me Until I Collapsed From A Heart Attack While Testifying…

Part One: If you’d met us seven years ago, you’d have said we were perfect. That’s what everyone said. “Clare…

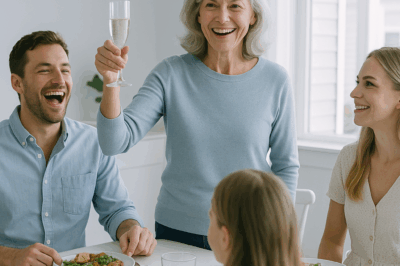

CH2 – “AT YOUR AGE, YOU SHOULD BE THINKING ABOUT DEATH, NOT DREAMS,” LAUGHED MY SON. BUT I MADE A TOAST!…

Part One: The candles on my seventieth birthday cake flickered like a row of tired stars, their flames trembling in…

CH2 – Lost My Kids & Husband to Sister’s Lies — 2 Years Later My 8yo Called Crying “Mom, Look What I Found”…

Part One If you’d asked me three years ago what happiness looked like, I would’ve pointed to the house on…

CH2 – At the Family Gathering, My Sister Publicly Called Me a ‘Cheapskate’ — But What I Did Next Silenced Everyone…

Part One: If you’ve ever walked into a place expecting love and walked out carrying heartbreak, you’ll understand me. My…

CH2 – Mom Said “You’re Just Jealous And Broke.” So I Froze Every Account—And 92 Calls Followed…

Part 1 My mother’s text came at 8:43 p.m. on a Tuesday night. You’re just jealous and broke. Don’t ruin…

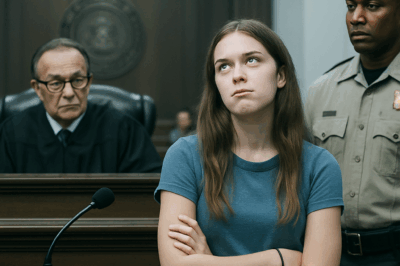

CH2 – Teen Girl Disrespects Judge Caprio in Court – Instantly Gets What She Deserves…

Part 1 Providence Municipal Court. Tuesday morning. 9:47 a.m. The heavy wooden doors swung open, and the click of expensive…

End of content

No more pages to load