Part 1

At 3:11 in the morning, a backhoe idled in my driveway like a dragon with heartburn. Its bucket hovered inches from the cedar shake roof I had spent six months restoring by hand. Diesel fumes mixed with fog, and the rhythmic hiss of hydraulics made my windows tremble.

I stumbled outside in flannel pajama pants and slippers, clutching my phone, heart pounding like I’d woken in someone else’s bad dream.

A woman in pearls and a tennis visor stood in the beam of the machine’s headlights, clipboard pressed to her hip like a sheriff’s badge.

“You have forty-eight hours or we flatten this pioneer hovel!” she screamed over the engine.

The operator—a weary man in a safety vest and the thousand-yard stare of someone paid just enough to ignore insanity—shrugged at me.

“Ma’am, it’s three in the morning,” I said, blinking. “You can’t—what—what is this?”

She jabbed her pen toward my cabin. “Section 9B of the community standards! Unsafe structures are subject to immediate abatement!”

Her voice was so shrill it sliced through the night. Windows lit up all down Sycamore Glenn Drive. Curtains twitched. Someone’s dog started barking.

That was how I officially met Sandra Withers, President of the Sycamore Glenn Homeowners Association. Seven years in power, self-appointed moral compass of the cul-de-sac, and self-proclaimed “guardian of suburban aesthetics.”

And me?

My name’s Owen Wrath—thirty-eight years old, divorced, quiet, mild-mannered, and allergic to conflict. I analyze data for a living. I collect old maps. I say “no worries” even when there definitely are worries.

All I wanted was peace and a place that didn’t smell like air freshener and HOA politics.

The Blackwell Cabin was that place.

Built in 1869 by a pioneer family, it sat at the edge of our development, where the neat lawns of Sycamore Glenn met the whispering pines. Everyone else saw a decaying log box that should’ve been bulldozed. I saw history—a place worth saving.

So, eighteen months ago, I bought it at a county tax auction for less than the price of a used car. It had been seized during an estate dispute. The siding was gray and brittle, the roof sagged, but the bones were strong. I spent evenings and weekends restoring it—by hand, board by board.

I learned how to split cedar shakes from YouTube and from a seventy-year-old craftsman named Dale, who smelled like tobacco and sawdust. I mixed lime wash using recipes from 1800s manuals. I hunted down square-head nails from salvage yards three states away.

Every shingle, every wavy-glass window pane was authentic. When I was done, the cabin looked like it had stepped out of a sepia photograph.

Sandra, however, saw it as an eyesore—a “frontier cosplay attraction” that clashed with her beige vision for the subdivision.

Her campaign against me began small.

A notice taped to my door: Unauthorized rustic aesthetic. Violation of bylaw section 7-12-f.

Except there was no section 7-12-f.

When I pointed this out during an HOA meeting, Sandra pursed her lips and fined me fifty dollars for “disrupting proceedings.”

Then came non-conforming fence height. I didn’t even have a fence—just an eighteen-inch cedar split rail around my herb garden. She measured it with a giraffe-shaped novelty yardstick, claiming it was “calibrated.”

Apparently, the giraffe didn’t lie.

I got another fine.

She accused me of using treated lumber (I wasn’t), forging receipts (I wasn’t), and planting “invasive vegetation.” That last one referred to my thyme plants, which she photographed at dawn like a detective at a crime scene.

But the real circus started when anonymous flyers began appearing in neighbors’ mailboxes:

Local man operates Frontier Cosplay Attraction — expect bonfires, goats, and possible health code violations.

Goats.

I didn’t have goats.

Mrs. Chen, from two doors down, asked if I’d be charging admission.

I laughed. She didn’t.

Then came an “emergency board meeting.” Three members—Sandra and two neighbors who looked perpetually trapped between fear and pity—voted my cabin an “attractive nuisance.” Sandra said it like she’d just invented the term.

She banged her walnut gavel and declared, “Your little log cabin fantasy ends now.”

That was when she sent the 48-hour demolition notice. Certified mail. Stamped with an eagle seal that looked suspiciously like it had been ordered from Etsy.

But Sandra wasn’t done.

She called county code enforcement three times in two days, pretending to be me. Claimed I’d discovered “black mold in biblical quantities” and a “rodent apocalypse.”

When inspectors actually showed up, they found nothing wrong. So she pivoted.

She hired a demolition company, prepaid them $4,000 out of HOA funds, and filed a “dangerous structure” complaint with—get this—the parks and recreation department.

The photo she attached wasn’t even my cabin. It was from a History Channel documentary about frontier cabins in Montana.

Then one night, she trespassed on my property and spray-painted a giant orange X across my restored door—the same door I’d spent three weeks sanding, repairing, and matching paint for.

She also cut the line to my security camera.

Unfortunately for her, I had a second camera.

And I had receipts—literal and figurative.

That night, while the backhoe idled like a dragon waiting for orders, I realized I was standing at the intersection of history and HOA madness.

And I decided—finally—that I wasn’t going to roll over.

The next day, I went to the county archives. The air smelled like dust and resolve.

That’s where I met Margaret, a librarian in her sixties with cat-eye glasses, a cardigan in July, and the aura of a woman who could find any document and win any argument using only her tone.

When I told her my story, she raised one eyebrow and said, “Let me see what we have.”

Twenty minutes later, she rolled out a cart stacked with leather-bound deed books, tax ledgers, and maps tied with string. Together we found it—the original Blackwell land patent, dated 1868.

And then she handed me the gold ticket:

A document from the State Historic Registry, filed five years ago. The cabin was officially protected as one of only three surviving pioneer structures in the county.

“Looks like your HOA president just threatened to demolish a state landmark,” Margaret said with relish. She labeled a folder Evidence for Mr. Wrath vs. Tyrant in perfect cursive.

I left the archives shaking with a mix of adrenaline and vindication.

By that afternoon, I’d filed for an emergency injunction with a lawyer who took the case on contingency.

“This,” he said, “is the most clear-cut abuse of HOA power I’ve seen in fifteen years.”

We called the State Historic Preservation Office.

The woman on the phone listened silently, then said, “Hold, please.”

It was the kind of hold that promised someone’s world was about to implode.

By sunset, my driveway was a scene out of a small-town thriller. A state preservation officer in a windbreaker. A county sheriff with a clipboard. And one very confused backhoe operator who kept apologizing and swearing he was “just doing his job.”

The officer confirmed it—the cabin was state-registered. The sheriff looked at Sandra’s fake seal and sighed.

“Ma’am,” he said, “you don’t get to invent government.”

The backhoe reversed slowly, beeping in retreat like a chastised animal.

The injunction landed at 6:47 p.m. Sandra’s empire cracked that very hour.

And that’s when things started to unravel.

Part 2

When the injunction papers hit Sandra’s mailbox, the entire subdivision vibrated with gossip.

Within 24 hours, Nextdoor lit up like a Vegas marquee.

“Emergency at Wrath’s Cabin!” one thread began.

“Police called to historic site dispute?” another speculated.

Someone even posted a blurry photo of the backhoe, captioned “Possible meth lab situation???”

By breakfast, half the neighborhood thought I’d been arrested.

By lunch, the other half thought I was a secret millionaire suing the HOA for ten million dollars.

Neither was true, though I did enjoy watching Sandra squirm in the middle of her own rumor tornado.

I didn’t see her for two days. When she finally emerged, visor tilted low, pearls clicking like nervous teeth, she was flanked by her two most loyal board members—Carol Pendergrass, who still used AOL email and considered decaf a sin, and Todd Simons, a man so conflict-averse he once apologized to his own lawnmower.

They went door to door with clipboards, spreading the gospel of “Property Values in Peril.”

I caught fragments of their pitch while raking leaves:

“Unsafe structure… liability nightmare… attracting unwanted attention.”

Unwanted attention?

She wasn’t wrong.

The State Historic Preservation Office had sent an investigator named Elaine Foster, a quiet woman in her forties with the unblinking stare of someone who had seen too many fake historic restorations. She carried a digital tablet, a laser measurer, and the aura of calm that only comes from wielding government authority.

She walked the perimeter of my cabin slowly, occasionally taking photos, occasionally muttering, “Remarkably well preserved.”

The sheriff stood beside her, jotting notes.

When Elaine finished, she looked at me and said, “Mr. Wrath, this is a legally protected structure under state law. Any demolition order issued without our authorization is invalid.”

Then she turned to the sheriff. “You’ll want to collect that seal she used. It qualifies as falsification of state emblems.”

Sandra, who had appeared halfway down the driveway like a groundhog smelling trouble, froze.

“Now, hold on,” she stammered. “I was acting in the best interest of the community!”

Elaine regarded her coolly. “The community doesn’t issue demolition permits, ma’am. The state does.”

It was the first time I’d ever seen Sandra’s confidence falter.

That night, I uploaded everything to the cloud:

Footage of Sandra spray-painting the X on my door.

Audio of her shouting at the backhoe operator.

The phony demolition notice with the Etsy eagle seal.

Her forged complaint to Parks and Rec.

I organized the files in folders labeled Evidence A through F and sent copies to my lawyer, Elaine, and—just for good measure—the local newspaper.

Within forty-eight hours, the Sycamore Glenn HOA was under state investigation.

The cracks spread quickly.

The board’s treasurer, Todd, resigned first. His “letter of departure” was written in Comic Sans and ended with, “I can’t keep explaining things I didn’t do.”

Then Carol called an emergency meeting at the clubhouse.

Sandra arrived fifteen minutes late, flanked by her husband, Gary, who looked like he’d rather be anywhere else, and wearing her trademark pearls of war.

I went too. I figured if they were going to keep playing HOA roulette with my life, I might as well watch the wheel spin.

The meeting started with Sandra slamming her walnut gavel, engraved with Wrath of Withers.

(I’d later learn she bought it online for $93 plus shipping.)

“This community,” she began, “is under attack by misinformation and outsiders who don’t understand our standards.”

Elaine, the state investigator, sat in the back row. So did the sheriff. So did Gerald, a forensic accountant with kind eyes and a satchel full of spreadsheets.

Sandra gestured toward me. “Certain individuals have taken it upon themselves to weaponize bureaucracy against honest volunteers—”

Elaine raised her hand. “Ma’am, the state is not a weapon.”

The room laughed—quietly, nervously.

Gerald stepped forward and cleared his throat. “I’ve been asked by the HOA’s legal counsel to review the financial records.”

He opened a binder thick enough to stun a moose.

“What I found,” he said, “is… concerning.”

Sandra’s husband coughed. Sandra’s pearls clicked faster.

Gerald continued: “Multiple unauthorized expenditures—including a $4,000 payment to Midwest Demolition Services, $180 to StickerPrintz.com for 500 custom ‘Unsafe Structure’ labels, and three separate orders of rubber seals marked ‘Official HOA Certified.’”

He flipped a page. “Also, a ceremonial gavel—labeled as ‘leadership enhancement tool.’”

Someone snorted.

Sandra’s voice cracked. “Those were administrative necessities!”

Gerald shook his head. “You also charged the HOA for $286 in ‘personal morale supplies’ from a craft store.”

Carol leaned in. “What’s that mean?”

He adjusted his glasses. “According to the receipt, two visors, a pearl polishing kit, and a novelty whistle set.”

The laughter wasn’t quiet this time.

Sandra slammed the gavel. “Order!”

The gavel head snapped off, bounced twice, and rolled under the vending machine.

I wish I could say I didn’t laugh, but I did. So did half the room. Even the sheriff bit his lip.

The aftermath came fast.

The HOA’s lawyer—who looked like he’d aged ten years in ten minutes—recommended Sandra step down pending investigation.

She refused.

She claimed it was all a “coordinated smear campaign.”

The state, however, didn’t deal in smear campaigns. They dealt in laws.

Elaine filed a formal complaint with the State Attorney General’s Office, citing possible fraud, misappropriation of funds, and destruction of protected property.

The AG’s office responded in less than a week.

Sandra received a letter requesting her “voluntary cooperation.”

She declined.

They sent a sterner one.

She hired a lawyer.

Then the HOA’s insurance company froze their accounts.

The neighborhood erupted like a pressure cooker.

People who’d lived under Sandra’s reign for years started comparing notes:

Fines for flower colors that “didn’t match the seasonal palette.”

Citations for “unauthorized wind chimes.”

Threats to confiscate Halloween decorations deemed “macabre.”

Someone started a group chat called Free Sycamore Glenn.

By day two, it had seventy members.

I mostly watched from the sidelines, trying to keep my head down while chaos bloomed around me. But there was one thing I couldn’t ignore: my cabin had become famous.

The local news station ran a story titled “Historic Cabin at Center of HOA Feud.”

They interviewed me on camera.

“So, Mr. Wrath,” the reporter asked, microphone glinting under the porch light, “what does this cabin mean to you?”

I looked at the wavy glass window behind her, the one I’d restored by hand. “It’s a piece of history,” I said. “But more than that—it’s a reminder that some things are worth standing up for. Even when it’s uncomfortable.”

The segment aired at 10 p.m. The next morning, my inbox had fifty messages—historians, preservationists, random strangers offering moral support.

Margaret from the archives emailed me one line:

“Well done, Mr. Wrath. Tyrants fall best when they trip over their own hubris.”

By mid-week, the HOA board called for a special session—open to all residents.

Rumor said Sandra planned to “clear her name.”

The clubhouse filled beyond capacity. Folding chairs lined the walls. The smell of microwaved popcorn hung in the air because, yes, people brought snacks.

I came early, laptop in hand, ready.

Sandra entered at 6:58 p.m., visor polished, pearls glowing under the fluorescent lights, and that same brittle confidence of someone trying to pretend gravity doesn’t exist.

She called the meeting to order with half a gavel.

“Neighbors,” she began, “you’ve been misled by false documents and slanderous media. I acted only out of duty to protect our homes from depreciation.”

A voice from the crowd shouted, “You tried to bulldoze history, Sandra!”

Another: “You fined me for having a birdbath!”

The sheriff entered through the side door, holding an envelope.

The room fell silent.

Sandra froze mid-sentence.

“Mrs. Withers,” he said, “I have a court order for your immediate removal from the HOA board, pending restitution hearings.”

She tried to hand him her gavel. It snapped completely in two.

Laughter again—louder this time, uncontrolled, cathartic.

The sheriff handed her the papers. “You’ll also need to schedule an appointment with the State Attorney’s Office. They’d like a word about your… creative documentation.”

Her visor slipped down over her eyes.

“This is outrageous!” she cried. “You’re all ungrateful! I made this neighborhood what it is!”

Someone in the back yelled, “Exactly!”

She stormed out. Pearls clattering. Doors slamming.

And just like that, the reign of Sandra Withers, HOA Queen of Sycamore Glenn, was over.

Afterward, Gerald the accountant sent me his final report:

Total misuse of HOA funds: $23,000.

Recommended restitution: Full reimbursement plus penalty interest.

Community morale: Recovering steadily.

He even added a handwritten note:

“P.S. I quit. Too much drama. Taking up pottery instead.”

I framed that one.

Elaine’s report to the state sealed the rest of it. Sandra’s actions had violated preservation statutes. The AG’s office fined her $23,000 and sentenced her to 200 hours of community service—specifically, cataloging historic artifacts under the supervision of one librarian named Margaret.

When I heard that, I nearly cried laughing.

Margaret emailed me again:

“Justice with cardigans, Mr. Wrath. My favorite kind.”

By the end of the summer, peace returned to Sycamore Glenn. The HOA elected a new board—three reasonable people who actually smiled.

Sandra’s house went up for sale. The listing described it as “lovingly maintained,” though I noticed the pearls didn’t make the photos.

As for me—I built a small plaque for the cabin door, carved by hand:

Blackwell Cabin (1869)

Restored and preserved by Owen Wrath, 2024.

State Historic Site — Protected by Law and Common Sense.

Neighbors stopped by sometimes, bringing coffee or baked goods, wanting to see the place they’d all heard about.

Even Mrs. Chen admitted, “You know, it’s actually… charming.”

I smiled. “Thanks. I try to keep the goats quiet.”

She laughed for the first time since I’d moved in.

That night, I sat on the porch beneath the warm glow of string lights, sipping bourbon. The air smelled like cedar and peace.

Somewhere down the street, a whistle blew—one long, defeated note.

I raised my glass to the sound and whispered, “Goodnight, Sandra.”

The cabin creaked softly in the breeze, like it was laughing too.

Part 3

When the dust settled—literally and figuratively—Sycamore Glenn began to feel like a town that had woken from a long, bizarre dream.

Lawns were still trimmed to regulation length. Mailboxes still matched. But something invisible had shifted in the air—like the neighborhood had exhaled for the first time in years.

For months, Sandra Withers had ruled the cul-de-sac like a monarch of beige, issuing decrees about acceptable mulch colors and the volume of wind chimes. Now she was gone, and in her place was a strange new phenomenon: neighborly freedom.

You could almost feel it at dusk when porch lights came on. People lingered outside. Kids chalked the sidewalks. Someone even installed a birdbath shaped like a flamingo—right on the corner lot. Under Sandra’s reign, that would have been a Class A misdemeanor punishable by two fines and a side of passive-aggressive newsletter entries.

Now it was just… cheerful.

I was still getting used to it. After so many months of tension—lawsuits, investigations, and late-night visits from county officials—the sudden calm felt suspicious. Like the universe had forgotten something.

Then, one morning, the local paper arrived with a photo that made me choke on my coffee.

There, on the front page, was Sandra Withers—in a county museum cardigan, her hair frizzed from humidity, pearls noticeably absent—cataloging old pottery shards at a folding table.

The headline read:

“Former HOA President Begins Community Service at Historic Museum.”

The photo captured her mid-scowl. You could almost hear the internal monologue: I’m surrounded by dust and peasants.

Margaret—the cardigan-clad librarian who’d saved my sanity—stood behind her in the photo, smiling faintly. I had no doubt she’d requested the assignment personally.

That clipping went straight on my fridge.

After the local coverage came the regional coverage.

A week later, a journalist from a national magazine called to ask for an interview.

“Your story,” he said over the phone, “is being shared on Reddit, Twitter, even a few home restoration forums. People are calling it ‘The Wrath of Withers Saga.’”

I snorted. “That sounds like a bad 80s metal album.”

He laughed. “Maybe so, but it’s gone viral. Folks love the underdog wins-against-entitled-HOA narrative. Would you be open to a feature piece?”

I wasn’t looking for fame, but I figured awareness might keep future tyrants in check.

So I agreed.

They sent a photographer—nice guy, mid-twenties, who brought his own step ladder. He spent three hours capturing the cabin from every angle. He asked me to pose with a hammer over my shoulder. I refused.

The article went live a month later under the title:

“The Man Who Stood Up to His HOA—and Saved a Piece of American History.”

It got shared thousands of times. People started driving by the cabin just to take pictures.

One family from Wisconsin even left a note in my mailbox: “We love what you did. You give us hope. HOA tried to fine us for sunflowers.”

My inbox overflowed with messages from strangers across the country. Some had horror stories about their own homeowners’ associations.

Others wanted restoration advice.

One woman from Arizona simply wrote: “Bless you for fighting the Beige Empire.”

Margaret emailed again, attaching a link to the article.

“I suppose you’re famous now,” she wrote. “Remember, celebrity is fleeting, but bylaws are forever. Guard your paperwork.”

I printed that too. Frame-worthy.

I hadn’t seen Sandra in person since her dramatic exit from the clubhouse meeting. But word traveled. Sycamore Glenn had a way of knowing everything without anyone saying anything.

First came the For Sale sign on her lawn. Then the whispers: her husband Gary had retired early and they were “downsizing.” A polite euphemism, I suspected, for “moving somewhere with no one who remembers the incident.”

During her last week in town, I saw her once—from my porch, late afternoon.

She stood by her mailbox, visor gone, holding a stack of envelopes. Her posture wasn’t the stiff, militant stance she used to have at board meetings. She looked smaller. Human, almost.

For a moment, I considered walking over—saying something gracious, maybe even forgiving. But then I remembered the orange X she’d spray-painted across my restored door, the sleepless nights, the forged notices, the lies.

I stayed on my porch, sipping coffee, watching quietly as she walked to her car and drove away.

The neighborhood didn’t cheer.

It just sighed.

Once the legal smoke cleared, I turned my attention back to what had started it all—the cabin itself.

Elaine from the preservation office connected me with a small grant for continued restoration. A local historical society offered volunteers. Suddenly, my quiet weekend hobby became a small community project.

Every Saturday, a few neighbors came by to help. Mr. Alvarez from across the street brought his grandkids. Carol—formerly Sandra’s right hand—showed up one morning with muffins and a guilty smile.

“I’m sorry,” she said simply. “I should’ve spoken up sooner.”

I handed her a paintbrush. “Then start with the window trim.”

Even Mrs. Chen contributed, donating potted lavender for the porch. “It repels bugs,” she said, “and tyrants.”

By summer’s end, the cabin looked better than I’d ever dreamed. The new lime wash gleamed under sunlight. The windows reflected the trees. And a small brass plaque by the door announced its historic status for all to see.

We held a little open house—free lemonade, cookies, and a short talk from Elaine about the preservation process. Dozens of people came, including a few reporters.

Kids asked if they could explore inside. I let them.

One boy pointed at the carved initials over the doorway—J. Blackwell, 1872—and asked if it was my name.

I smiled. “Nope. He was here long before me. But I think he’d be glad we saved his home.”

That night, as the crowd thinned and the sun dipped behind the pines, I sat on the porch again, watching the fireflies. It hit me how full-circle it all felt—how something so absurd, so stressful, had turned into something beautiful.

Maybe that was the universe’s sense of humor.

By autumn, “The Wrath of Withers” had become local legend.

Teenagers used it as shorthand:

“Don’t pull a Withers,” they’d say when someone overstepped.

The new HOA board—made up of actually reasonable humans—instituted a “Community Feedback Policy.” No more secret fines. No fake bylaws. Meetings were now recorded and publicly posted.

They even added a new clause to the bylaws, unofficially dubbed The Wrath Rule:

Section 12.4(b): “No officer or member shall take unilateral action affecting another resident’s property without documented authorization and full board approval.”

It was, essentially, a legal way of saying don’t be a Sandra.

At the annual block party, the new president, Janice Porter, raised her cup of lemonade and toasted me publicly.

“To Owen Wrath,” she said, “for proving that history—and sanity—can coexist in Sycamore Glenn.”

Everyone cheered.

I didn’t know where to look.

I just nodded and said, “No worries.”

Because old habits die hard.

Months later, on a rainy Thursday, I found an envelope in my mailbox with neat cursive handwriting. No return address. Inside was a short note:

Mr. Wrath,

I’ve had time to reflect. I took things too far. Perhaps I forgot that preserving beauty doesn’t mean controlling it. For what it’s worth, I did admire your craftsmanship.

—S.W.

No pearls, no threats, no legalese. Just that.

I stared at it for a long time. Then I folded it carefully and slipped it into the folder labeled Evidence for Mr. Wrath vs. Tyrant. It felt fitting that her apology would live among the wreckage she’d created.

That evening, I went to the museum where she was serving her community hours. Margaret met me at the door.

“You here to see the exhibit or the exhibit’s penance?” she asked dryly.

“Maybe both.”

Sandra was at the far table, cataloging 19th-century glass bottles, her hands steady, her face unreadable. She looked up once, caught my eye, and nodded. A brief, wordless truce.

I nodded back, then turned and left. It was enough.

Winter came. Snow blanketed the cabin roof.

Inside, I built a fire and watched the light dance across the old wooden beams. The place creaked, warm and alive.

Sometimes, when the wind blew through the trees, I could swear the house whispered. Maybe just the wood expanding, maybe something older. Either way, it felt like gratitude.

The story eventually faded from headlines, replaced by new scandals, new distractions. But in Sycamore Glenn, it lingered in the collective memory like a campfire story parents told their kids:

“Once upon a time, a man bought a cabin, and a lady in pearls tried to bulldoze it at midnight. But history fought back.”

And somewhere in the retelling, I became less of a guy in pajamas arguing with a backhoe and more of a folk hero—The Man Who Saved the Cabin.

I didn’t mind.

Every legend starts with someone refusing to back down.

Even the quiet ones.

That spring, a letter arrived from the State Historic Society. They wanted to designate the cabin as an official heritage site, complete with a roadside marker.

I stood on the porch, reading the letter, the smell of cedar and rain in the air, and smiled.

Somewhere, I hoped, J. Blackwell was smiling too.

Part 4

The snow had barely melted when the letter from the State Historic Society turned into something bigger.

They didn’t just want to recognize the Blackwell Cabin.

They wanted to research it — properly, archivally, like historians with white gloves and scanners and words like “artifact integrity.”

At first, I figured it would be a simple plaque dedication. Maybe a few speeches, a ribbon cutting, coffee in styrofoam cups.

But within weeks, the cabin became a small academic magnet.

The Society sent Dr. Helen Kearney, an architectural historian from the state university, along with a grad student named Malik, who had a camera drone and the enthusiasm of a golden retriever.

Their first day on site, Helen ran her hand across the front lintel, tracing the carved initials.

“J. Blackwell,” she murmured. “He wasn’t just any settler. He was one of the first documented carpenters west of the river. Built three churches, two barns, and—” she checked her notes—“vanished in 1881.”

“Vanished?” I asked.

She nodded. “There’s a note in the county ledger: ‘Property left vacant after the Great Storm.’ No heirs. No sale.”

That phrase—The Great Storm—hit something deep.

The storm that year had torn through the Midwest, erasing whole towns.

“Maybe he didn’t vanish,” I said. “Maybe he just didn’t make it.”

Helen smiled faintly. “Perhaps. But buildings like this? They’re time capsules. Sometimes they talk.”

It started with the floorboards.

One chilly afternoon, Malik knelt by the hearth, shining a flashlight into a seam between the planks. “Hey, Mr. Wrath,” he said, “you ever notice these?”

He pried up a loose board carefully. Underneath, the wood was dark and smooth — and carved.

Tiny initials, dates, and what looked like a symbol — two interlocking circles.

Helen crouched beside him. “That’s a family mark,” she said quietly. “They used to do that to claim lineage or ownership. This cabin might’ve been a workshop.”

I felt a jolt of pride, like the cabin was revealing its secrets to me personally.

They found more carvings along the beams—short inscriptions in faint, looping cursive.

Helen photographed each one, then read aloud:

“‘Jonas Blackwell, 1871. Mary’s prayer keeps this roof strong.’”

That line gave me goosebumps.

“Mary was his wife,” Helen said softly. “She died young. There’s a headstone with her name in the old cemetery off Route 8.”

I realized I’d driven past that cemetery dozens of times.

“Jonas must’ve built this place for her,” she said. “A promise kept in timber.”

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I sat by the fireplace, listening to the old logs creak, and imagined Jonas carving that inscription by lamplight, each stroke of his knife a vow.

It made every splinter, every hour I’d spent restoring this place feel like I’d been part of something much larger than me — a continuation of care.

By May, the dedication ceremony was set.

The state approved an official roadside marker. The local paper ran another story:

“Historic Blackwell Cabin to Receive Heritage Designation — Once Targeted by HOA, Now Protected Forever.”

The morning of the event, the sky was so blue it almost looked painted.

Dozens of people showed up—neighbors, preservationists, even Margaret from the archives (wearing her signature cardigan despite the heat).

Elaine Foster, the preservation officer, was there too, clipboard in hand.

She greeted me with her usual calm smile. “Well, Mr. Wrath. You’ve caused quite the ripple.”

“I try to use my powers only for good,” I said.

She chuckled. “Good. Let’s keep it that way.”

At ten sharp, the ceremony began.

Janice, the new HOA president, gave a brief introduction, highlighting “the importance of community collaboration.” (Translation: Let’s never have another Sandra situation.)

Then Helen stepped up and told the story of Jonas and Mary Blackwell — the carpenter and his wife, their home, their legacy.

When it was my turn, I kept it simple.

“I’m not a historian,” I said into the microphone. “I just saw something worth saving. I didn’t build this cabin, but maybe in some small way, I helped it keep standing a little longer. I think Jonas would’ve wanted that.”

There was quiet applause, the kind that comes from genuine warmth.

Then they unveiled the plaque.

BLACKWELL CABIN (1869)

Built by Jonas Blackwell, pioneer craftsman.

Preserved by the State of Illinois and citizens of Sycamore Glenn.

Restored 2024 by Owen Wrath.

For a man who liked quiet weekends and spreadsheets, I’d somehow ended up immortalized in bronze.

I wasn’t sure how to feel—humbled, mostly. And a little amused.

Margaret clapped the loudest. “Well done, Mr. Wrath,” she said afterward. “You’ve joined history’s stubborn people. It’s the best company there is.”

A week later, a rust-colored pickup truck rolled into my driveway.

The man who climbed out looked about sixty, with calloused hands and eyes that squinted against years of sunlight.

“Name’s Ray Blackwell,” he said, shaking my hand. “You’re the fella who saved my great-great-grandfather’s cabin.”

I blinked. “You’re—wait—you’re related to Jonas?”

He nodded. “Didn’t even know it was still standing till I saw the article online. My granddad used to tell stories about the old homestead, said it vanished after the storm.”

He ran his hand along the logs like he was touching the past itself. “Can’t believe it’s real.”

We walked the perimeter together. He pointed to a notch in the wall. “That’s his mark. He used to sign his work with that little ‘J’ carve. I’ve seen it on an old chest in my mother’s house.”

Inside, he stood by the hearth and grew quiet.

“My family lost everything after that storm,” he said softly. “But this—this survived. I can’t thank you enough.”

I shrugged. “Just did what felt right.”

He smiled. “You did more than that. You gave my family its story back.”

Before he left, he handed me a small wooden box. “Found this in my attic years ago. Thought you should have it.”

Inside were two items: a yellowed photo of Jonas and Mary standing in front of the cabin, and a folded letter dated 1871.

The handwriting was shaky but legible:

If you find this home, know that we built it with faith and sweat. May whoever keeps it next do so with care, and may this roof always hear laughter again.

— J. Blackwell

I didn’t realize I was crying until the ink blurred.

That evening, I framed the photo and hung it by the hearth.

The letter went into a shadow box beside it.

Every night since, when the fire flickers across those two faces frozen in sepia, I swear I can almost see them smiling — proud, maybe even relieved.

Because in the end, that’s what all of this was about: not victory, not revenge, but continuity.

One man’s stubborn devotion meeting another’s century later.

Sometimes I think about Sandra, somewhere out there cataloging artifacts, touching the same kind of old wood, the same handmade tools.

Maybe she finally understands what it means to preserve rather than destroy.

I hope so.

Summer rolled around, and with it came another envelope—this one embossed with a gold seal (a real one this time).

The state invited me to speak at the annual Historic Preservation Gala in Springfield.

The theme? “Ordinary People, Extraordinary Impact.”

I laughed out loud reading it.

Me, the introverted data analyst who once panicked over a lawn fine, was now keynote material.

I went anyway.

When I stepped onto that stage months later, surrounded by historians and officials in suits, I looked down at my notes, then out at the crowd.

“Sometimes,” I began, “history isn’t found in archives or textbooks. Sometimes it’s sitting on the edge of a suburb, waiting for someone stubborn enough to listen.”

I told them about the cabin, about the 3 a.m. backhoe, about the librarian with weaponized politeness, the accountant with ceramic frogs, and a community that rediscovered its backbone.

I ended with the line from Jonas’s letter.

There was silence—then applause that felt like thunder.

Afterward, Helen found me. “You should’ve been a writer,” she said.

“Too much paperwork,” I replied. “I’ll stick to cabins.”

That night, driving home under a canopy of stars, I passed the new roadside marker glowing under the headlights.

BLACKWELL CABIN (1869)

It gleamed like a promise.

I slowed down, rolled down the window, and listened.

The crickets. The faint rustle of the pines. The same sounds Jonas must’ve heard a hundred and fifty years ago.

History wasn’t just old—it was alive.

Part 5

The first summer after the preservation gala, Sycamore Glenn bloomed in ways it never had before.

Without Sandra’s surveillance, color crept back into people’s yards like a timid animal rediscovering trust.

Porches filled with mismatched chairs. Someone painted their front door teal. Carol Pendergrass hung a hammock between two trees and dared anyone to fine her.

No one did.

The HOA newsletter even changed its name from The Sycamore Sentinel to The Glenn Gazette.

The first issue featured an article titled “Community Spotlight: The Cabin That United Us.”

It felt good—normal, finally. Like the neighborhood had found its rhythm again.

But peace, I learned, isn’t just the absence of conflict.

It’s the presence of understanding.

Late one July morning, I got an unexpected email.

Subject line: “A Small Request – S. Withers.”

For a moment, I thought it was spam. Then I read:

Mr. Wrath,

I know I am likely the last person you wish to hear from, but I wondered if you might allow me to visit the cabin one last time. I’ve been working at the museum, as you know, and have learned more about the value of what I nearly destroyed. There’s something I need to say in person.

Respectfully,

Sandra Withers.

I stared at the screen for a long time.

Part of me wanted to delete it.

Another part—the part that restored an entire cabin with patience instead of anger—said maybe closure wasn’t for her alone.

So I replied.

Come by Saturday at noon. The porch will be open.

Saturday arrived bright and windless. The pines whispered softly, as if curious themselves.

When Sandra pulled up in her silver SUV, I hardly recognized her. No visor. No pearls. Just a simple blouse and jeans.

She looked smaller, lighter somehow.

She paused at the edge of the porch. “It’s beautiful,” she said quietly. “I never really saw it before. I just saw what I thought it should be.”

I nodded, letting her words hang in the air. “History doesn’t need approval,” I said. “Just care.”

She smiled faintly. “You’re right. I was wrong. About this place… about you… maybe about a lot of things.”

We walked inside. Sunlight filtered through the wavy panes, scattering across the floorboards Jonas had once carved.

Sandra stopped before the shadow box with the Blackwell letter.

She read it silently, then looked at me. “He said, ‘May this roof always hear laughter again.’ I suppose it has.”

Her voice trembled slightly. “You should know, I’ve been volunteering extra hours at the museum. They asked me to help with a new exhibit on civic responsibility. The irony’s not lost on me.”

That made me smile. “Life has a sense of humor.”

She exhaled. “I’m leaving Illinois next month. Moving near my daughter in Oregon. But before I go, I wanted to say thank you—for not turning this into vengeance.”

I thought of the night she’d spray-painted the X across my door, of the sirens, of the courtroom.

Of the months I spent rebuilding what she’d tried to erase.

“You already punished yourself more than I ever could,” I said softly.

Sandra nodded once. Then she reached into her bag and handed me a small box.

Inside was a gleaming brass nameplate engraved with elegant cursive:

The Wrath of Withers – 2024.

To those who learn the hard way.

I laughed before I could stop myself. “You kept the gavel plate?”

“Consider it irony therapy,” she said. “Goodbye, Mr. Wrath.”

“Goodbye, Sandra.”

She left quietly. No pearls clicking, no whistle. Just the sound of her car disappearing down the road, swallowed by summer air.

Two weeks later, I got another visitor—Ray Blackwell again, this time with his granddaughter, a teenager named June.

“She’s doing a school project on family history,” he said. “Thought she should see where it all started.”

June wandered through the cabin, wide-eyed. “It’s like stepping into a time machine,” she whispered.

When she saw the old photo of Jonas and Mary, she smiled. “They kind of look like us.”

Ray chuckled. “Good bones, bad haircuts.”

I showed them the letter, the tools, the preserved marks in the beams. June took photos for her report.

Before they left, she asked, “Mr. Wrath, can I quote you in my project?”

“Sure,” I said. “What for?”

She grinned. “My teacher asked what the lesson of all this was. I want to say, ‘You can’t bulldoze history—or decency.’”

I nodded. “That’s a good line. Better than I could’ve written.”

When they drove off, I stood there watching their taillights fade, thinking how stories echo in ways we can’t predict.

A man builds a home.

A stranger saves it.

A child learns from it.

And somewhere in between, time loops back on itself.

By autumn, the cabin had become a minor tourist stop—nothing official, but enough that people sometimes left notes on the porch rail.

Most were simple: “Beautiful restoration.”

Others more poetic: “My grandmother grew up in a place like this. Thank you for keeping it alive.”

One note, written on lined notebook paper, simply said: “If walls could talk, they’d thank you.”

That one I taped to the inside of the door.

The nights were quiet again. I’d sit on the porch with a mug of tea, listening to the chorus of frogs down by the creek. The cabin, once a battleground, now felt like the calm center of a story finished properly.

Sometimes, the faint smell of cedar smoke mingled with the cool air, and I thought of Jonas.

How he must’ve stood in the same spot, watching the same moon rise above these same trees.

History, I realized, isn’t just what we inherit. It’s what we choose to protect.

One cold December morning, my phone rang.

Margaret’s voice came through, crisp and amused as ever.

“Mr. Wrath,” she said, “I just received a donation of historic documents from a certain Mrs. Withers. Included was a folder labeled ‘Lessons Learned.’ Inside was a printed photo of your cabin.”

I laughed. “That’s almost… sweet.”

“She also enclosed a check for the county library’s preservation fund,” Margaret added. “Five thousand dollars.”

That stopped me cold.

Maybe people really do change.

“Consider the arc complete,” Margaret said. “Tyrant to benefactor. I’m retiring soon, you know. But I’ll leave a note in the archives: ‘Wrath vs. Withers—case study in poetic justice.’”

“Make sure it’s in the Dewey Decimal system,” I said.

She chuckled. “Always.”

On New Year’s Eve, I started a journal for the first time in years.

The first entry was short:

The cabin stands. The past breathes. The quiet feels earned.

Outside, fireworks flickered above the trees.

I watched their reflections ripple across the cabin windows, and for a moment, the glass looked like water — shimmering with color and life.

I thought about everything that had happened:

The backhoe at 3 a.m.

The fines.

The courtroom laughter.

The applause at the plaque unveiling.

The strange, unplanned community that had grown from all of it.

It struck me then that this was what home truly meant—not just a roof, but the stories it holds.

A year later, the state added a small secondary marker beside the main plaque:

SITE RESTORED THROUGH COMMUNITY EFFORT, 2024.

Proof that a neighborhood can remember how to care.

Tourists still came by sometimes.

Sometimes they met me, sometimes they didn’t.

But every visitor paused under that lintel, tracing the carved initials. And each one, whether they knew it or not, became part of the story.

One afternoon, a little boy looked up at me and asked, “Did you build it?”

I smiled. “No. But I made sure it stayed standing.”

He thought about that for a second, then said, “That’s even better.”

And maybe it was.

As evening fell, I lit a lantern inside. Its glow filled the cabin, flickering across the walls, steady and warm.

Outside, the pines swayed gently in the dusk, whispering their approval.

Somewhere out there, the past rested easy.

And for the first time in years, so did I.

THE END

News

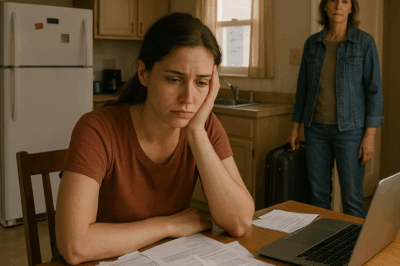

CH2 – My Mom Made Me Pay Her Bills for 11 Years — Then Left Me When I Needed Her Most…

Part One: If you had asked me at twenty what love meant, I’d have said: devotion. Not the movie kind,…

CH2 – MY WIFE SENT ME FLOWERS AT WORK ON VALENTINE’S DAY. MY COWORKER, A FORMER MEDICAL STUDENT…

Part 1: The flowers were bright, too bright—like a stoplight you don’t notice until you’re already in the intersection. A…

CH2 – Brother Sold My “Abandoned” House — It Was a Protected Federal Witness Property Worth $900K…

Part 1 The seventieth birthday cake was a hazard the insurance adjusters would have sighed about—seventy thin sticks of fire…

CH2 – DURING MY VASECTOMY PROCEDURE, I OVERHEARD MY SURGEON TALKING TO A NURSE: “IS HIS WIFE STILL IN THE WAITING ROOM?”…

Part 1 The anesthesia was supposed to make everything go quiet. It didn’t. The world went soft around the edges—gray,…

At My Dad’s Funeral, My Mom Was Traveling With Her Lover — But What Happened That Night…

Part 1 The rain came sideways that morning — the kind that never stops, the kind that turns a funeral…

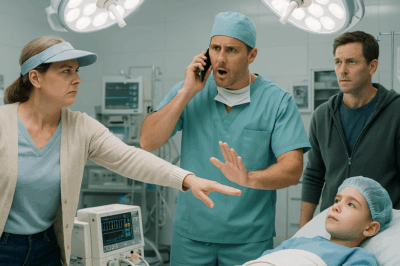

CH2 – HOA Karen Tried To Delay My Son’s Surgery—Doctor Called Police When She Touched Equipment…

Part 1: If you had asked me five years ago why I bought a house in Cedarbrook Landing, I would’ve…

End of content

No more pages to load