At 8:43 on the morning of August 15th, 1943, First Lieutenant Kenneth Walsh watched his wingman scatter across the sky above Vella Lavella and knew two things with cold, mechanical certainty.

In about ninety seconds he was either going to die…

…or he was going to do something no American pilot had ever done before.

The sky over the Solomon Islands was that washed-out Pacific blue that made distances lie. The sea 19,000 feet below looked like brushed aluminum. A few stray clouds drifted, useless for cover. Sunlight flashed on wings and canopies, on spinning propeller hubs, on the blunt noses of bombers that suddenly looked very small and very alone.

Walsh’s Corsair—F4U-1, bent wings, big nose, 2,000 horses pushing him through thin air—shuddered as he rolled level. His right hand sat on the throttle, palm sweaty inside his glove. His left gripped the stick, steady, knuckles pale but not white. He could feel the engine’s vibration through the seat, through the rudder pedals, through his teeth.

His section leader was gone. One 20mm shell through the cockpit from a diving Zero, and the man was just…meat and smoke. The wingman had broken formation in blind panic, pitching into a useless downhill turn that took him straight through a curtain of tracers. Someone else had bailed out, parachute a white flower far below that would probably never open fully before a Zero found it.

Walsh was alone at 19,000 feet.

Alone with fifty Zeros.

He saw them as specks at first. Then as shapes. Then as teeth.

They were coming down out of the high sun, out of Rabaul. Fifty Mitsubishi A6M fighters—thin, elegant, lethal. Fifty of the most maneuverable aircraft in the Pacific, flown by pilots who had been fighting since Wake and the Marshalls. Their average combat hours beat his by a factor of four. Some of them had more time in a cockpit than he had on the planet.

They were angling not for him but for the bombers below.

Twelve TBF Avengers, each lugging a torpedo, each with three men aboard. Thirty-six Americans moving at 180 knots, fat, level, focused on their own run-in toward Japanese supply lines.

American doctrine was clear as scripture: Outnumbered more than three-to-one? Disengage. Extend. Live to fight another day. One fighter pilot wasn’t worth a bomber formation. But one fighter pilot and the entire formation? That was disaster math.

Walsh’s thumb rested on the gun switch. Six .50-caliber Brownings in his wings, 2,300 rounds of ammunition that suddenly felt like drops in a very large bucket.

He could almost hear his instructors: If you are badly outnumbered, your job is survival, Lieutenant. Get out. Don’t be a hero. Heroes are just dead men with good press.

He looked down. The Avengers droned on, oblivious for the moment. He pictured the crews: pilots checking gauges, radiomen hunched over sets, gunners peering into the empty blue, trusting the thin layer of fighter cover above their heads.

Fighter cover that no longer existed.

Fifty Zeros. Twelve bombers. One Corsair.

Walsh had ten seconds to decide which list he belonged to.

He took a breath. Felt it fill his lungs. Felt the engine’s torque trying to twist the airframe. Felt the way the nose wanted to yaw left as the prop bit and bit and bit into air.

He’d felt that kind of twist before.

Not in a cockpit.

In a garage in Brooklyn.

In 1930, the engines he listened to were flathead Fords and worn-out Chevys, not Pratt & Whitney Double Wasps. The air smelled of oil and gasoline and hot metal instead of hydraulic fluid and avgas. The soundscape was different but the logic was the same.

Systems. Always systems.

The sign over the garage door on Flatbush Avenue read “Patrick Walsh & Sons Automotive,” though Patrick Walsh had only one son and only one nephew, and neither of them had been consulted when the paint was slapped on in 1923. It was already peeling by the time young Ken learned how to spell his own last name.

His father had worked the docks until a crane cable snapped and physics turned lethal. Ken was thirteen. His mother was suddenly a widow with more bills than options. School became a luxury they couldn’t afford. The day after his fourteenth birthday, Ken stood under that crooked sign while his uncle held a rag between his hands and looked him over.

“You listen,” Uncle Pat said. “You listen to the machines. They’ll tell you what’s wrong if you pay attention.”

For six years, Ken Walsh took things apart and put them back together.

He learned that a knocking sound under load wasn’t just “a knock”—it might be a bad con-rod bearing, or detonation, or timing. Each problem had symptoms that connected to causes, and the causes connected to other systems.

A slipping clutch wasn’t just a clutch. It was wear on the friction surface, sure, but it was also the way torque loaded the transmission. A brake pull under hard pedal didn’t just mean “something wrong with the brakes”; it meant weight transferring forward, a sticking cylinder here causing drag there, fluid pressure different left and right.

“You can’t fix one thing in isolation,” Uncle Pat said one afternoon, both of them elbow-deep in the undercarriage of a ’36 Ford. “Engine makes torque. That torque goes down the shaft, into the differential, out to the wheels. Every place that force passes through, it changes something.”

He rapped the drive shaft with his knuckles.

“You balance this wrong, the whole car shakes. Customer complains about the steering, not the shaft,” he went on. “So if you only look at the wheel, you never solve the real problem. You think about the system, Kenny. Always.”

By 1941, Kenny could listen to an engine idling two blocks away and tell you if the valves needed adjusting. He could take a car around one corner, feel a vibration at thirty miles per hour, and say, “Left rear bearing’s going. Two weeks until it fails. Three if you’re lucky.”

Forty-two dollars a week. Enough to keep his mother fed. Enough to buy himself the occasional new shirt and dream, quietly, about a shop of his own someday.

Then December 7th happened.

On the morning of December 8th, the line at the Marine Corps recruiting station on Court Street curled out the door and halfway down the block. Kenny stood in it, hands in his pockets, heart beating hard.

“What can you do, son?” the recruiter asked when his turn came.

“Fix engines,” Walsh said. “Cars, trucks. Probably planes, if you show me how they come apart.”

The recruiter looked at his test scores. Mechanical aptitude in the rafters. Spatial reasoning like a draftsman. Problem solving off the charts.

“The Corps doesn’t need another mechanic,” the recruiter said. “We need pilots.”

Walsh blinked. “I don’t know how to fly.”

“We’ll teach you.”

“I signed up to turn wrenches,” Walsh said, stubborn.

The recruiter leaned his elbows on the desk. “Look, kid. You can fix one plane at a time on the ground…or you can keep a dozen from coming home on fire. You’re too smart to live under a hood your whole life. This war needs brains in cockpits.”

Walsh thought about it. Thought about his uncle, about his mother, about Pearl Harbor, about the pictures in the newspapers. He thought about the way engines felt under his hands and the idea of being inside the machine instead of under it.

“Okay,” he said. “Show me.”

If the recruiter had told him they were sending him to die in training, he might’ve reconsidered.

The Corsair looked like something a kid would draw if you asked him to sketch “airplane with the biggest engine possible.” Giant round nose. Bent wings. Long fuselage. It sat on the ramp at Pensacola like a predator that hadn’t decided who it was going to eat yet.

They called it the Ensign Eliminator. The Widowmaker. Hog. Bent-wing bastard.

Between February and August 1943, the Navy lost seventy-six of them in training accidents. Not combat. Training. Fifty-four pilots died without ever seeing a Japanese round.

It wasn’t malice. It was physics.

The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp was eighteen cylinders of American overkill. Two thousand horsepower. The propeller up front was thirteen feet in diameter and turned clockwise when viewed from the cockpit.

Newton’s Third Law didn’t care about nicknames. The prop spun one way, the airframe wanted to roll the other. At low speeds, when the ailerons didn’t have much bite, that torque could flip a Corsair onto its back before a pilot could say oh hell.

Most students fought it.

On takeoff, they’d shove the throttle forward, feel the plane start to yaw and roll left, and haul the stick right with white-knuckled fury. Sometimes they’d win the tug-of-war. Sometimes they wouldn’t. Sometimes the aircraft would begin to oscillate—left, right, left again, magnifying each time—until one wing grabbed more lift than the other and the whole thing cartwheeled.

From the ground, it looked like a toy tossed by a drunk child.

Walsh’s first few flights left him exhausted. He could handle the mechanics—gear up, flaps up, power settings—but every takeoff felt like wrestling a bull.

On his third training flight, they climbed to 8,000 feet over the Gulf, Pensacola a hazy smudge behind them. His instructor, Captain Robert Fraser, rode in the other Corsair in their little two-ship, watching him.

“Okay, Walsh,” Fraser said over the radio. “Power-on stalls. Bring her to the edge, hold it, then recover on my command.”

Walsh pulled back, feeling the buffet, the shudder that said, You’re almost out of lift. He held the nose high. Fraser’s voice came calm.

“Now add power.”

Walsh pushed the throttle forward. The Corsair’s engine thundered. The nose wanted to yaw left. The left wing dipped. Walsh fought it, cranking in right aileron, then more when that seemed to do too much, then back left.

The plane rocked like a drunk on ice.

“Relax your grip, Walsh,” Fraser said. “You’re strangling the stick.”

“I’m trying to keep it level, sir,” Walsh grunted.

“You’re trying to cancel out two thousand horsepower with your forearms,” Fraser replied. “How’s that working?”

Walsh gritted his teeth. His shoulders ached. Sweat ran down his back.

“Not great, sir.”

“Exactly.” Fraser’s tone changed. Less drill instructor, more…teacher. “Listen. The torque’s constant at a given power setting. It’s not random. It’s a steady force. You don’t fight a steady force moment by moment. You balance it.”

Walsh frowned. “Sir?”

“Set your trim and aileron for what you know the plane is going to try to do,” Fraser said. “Not what it’s doing right this second. Let it want to roll left. You just control how far it gets.”

The words dropped into Walsh’s brain and hit something that had been waiting since a Ford drive shaft in Brooklyn.

Torque doesn’t just hit one part, kid. It goes everywhere. You don’t fight it with your hands—you account for it in the whole system.

Walsh eased back the throttle, leveled off, and took a breath. He looked at his trim wheels, at the little tab indicators. He thought about how much rudder he normally had to kick in to keep the nose straight during a full-power climb. He thought about how much aileron he ended up holding.

Then he did what he’d always done in the garage: he tried to fix the problem before it made noise.

He rolled a few degrees of right rudder trim in. Dialed in a hint of right aileron. Got the plane flying hands-off straight and level at cruise.

“Okay, sir,” he said. “Again.”

“Your show,” Fraser replied.

Walsh eased back on the stick, brought the nose up, felt the buffet start again. The Gulf spread out below, steely and indifferent. He added power smoothly, watching the needle climb, feeling the engine load.

The nose wanted to yaw left.

The trimmed-in rudder pushed back.

The wings wanted to dip.

The ailerons he’d set quietly said, Not so fast.

The aircraft didn’t lurch or buck. It simply…accepted the power.

Walsh held the attitude. No wrestling. No overcorrection. The stick was light under his hand, not a barbell.

“Fraser, you see that?” Walsh said, hardly believing it.

On the other end, a low whistle came through the headset.

“What did you just do, Lieutenant?” Fraser asked.

Walsh tried to explain: torque, systems, anticipating instead of reacting.

Fraser was quiet for ten full seconds.

“Whatever that was,” he said finally, “keep doing it.”

Walsh did.

He set trim before he moved the throttle. He thought about where forces would go, not where they already were. On takeoff, he rolled in rudder trim, took a breath, pushed the throttle in slowly until he felt the tail lift. His ailerons were already whispering no to the torque before it shouted.

Where other students fishtailed and bounced and occasionally broke things, Walsh’s Corsair went straight, lifted clean, and climbed.

His landings smoothed out. His aerobatics sharpened. He burned less mental energy on just keeping the wings level and had more left to think tactically.

The instructors noticed.

“Mechanically perfect,” Major Gregory Grace said after watching one of Walsh’s check flights. “He flies like he can already see what the plane’s going to do five seconds from now.”

Walsh didn’t think of it that way. To him, it was just fixing the system.

By the time he graduated in February 1943, he had 112 hours in the Corsair. More than half of them were spent not just flying but demonstrating to other pilots. “Set your trim before you need it, not after you’re already in trouble,” he’d say, tracing little diagrams in the air with his hand. “Stop fighting and start balancing.”

In May, he shipped out to the Pacific with 189 hours in type and a record that was, on paper, boring: zero accidents, zero ground loops, zero go-arounds.

In a war that was burning through pilots like kindling, “boring” was starting to look like genius.

The Solomons in mid-’43 were a long way from Brooklyn, but the logic of the machines hadn’t changed.

The first time Walsh saw a Zero for real, it was coming down out of the sun over Rennell Island, a sliver of white fire against a too-bright sky.

“Bandits, eleven o’clock high, two miles!” someone shouted over the radio.

Walsh craned his neck. He was on Ken’s wing—today it was Ken in his own head, not Lieutenant Walsh—flying cover for a flight of SBDs. His Corsair hummed steady, engine happy in the cool air above the water.

The Zero slid into view, more graceful than any training silhouette. It rolled, diving, nose pointed at the formation.

Walsh’s hand moved almost on its own. He pushed the nose down, not toward the Zero, but away. Down meant speed. Speed meant energy. He felt the Corsair accelerate, the airframe humming as they passed 300 knots, then 350.

He didn’t try to turn into the Zero. The Japanese pilot wanted that: a turning fight, a spiral of decreasing circles where the lighter Zero could cut inside his arc and fill his cockpit with fire.

Walsh went vertical instead.

He pulled back hard. The Corsair arced up, up, converting all that horizontal speed into altitude like a roller coaster cresting a hill. The G-load pressed him into his seat, his vision graying at the edges.

Below, the Zero tried to follow.

Gravity and the laws of horsepower didn’t care about reputation. At that speed, climbing at that angle, the Zero’s engine was working past what it could really give. The nose rose, the airspeed bled off, and the elegant killer from Rabaul started to wallow.

Walsh felt his plane reach the top of its climb, momentary weightlessness, then pushed the stick forward and rolled. Inverted. Nose pointed down now, the Zero laid out in his windscreen, fat and slow and right where math had put it.

He squeezed the trigger.

In the Pacific sky, Jack London’s wolves were made of rivets and aluminum, and the only law of the wild that mattered was energy.

By mid-July, he had three kills.

Not flukes. Not “got lucky, hit him from behind.” Each one the result of that same kind of thinking: speed isn’t just “fast,” it’s stored altitude. Altitude isn’t just “high,” it’s stored speed. You spend one to buy the other, and if you keep your books balanced better than the other guy, you live.

He taught his wingmen to do it. Some listened. Some didn’t. The ones who listened tended to come back with more paint on their kill flags.

But nothing he’d seen, nothing he’d done, nothing he’d read in tactics manuals, had prepared him for the sight of fifty Zeros all at once.

Now, above Vella Lavella, Walsh felt the old habits slide into place.

Check trim. Check fuel. Check ammo counters. Twelve Avengers below. Fifty Zeros above. Airspeed 240 knots. Altitude 19,000 feet. Engine temperature nominal. Oil pressure good.

His radio was a chaos of overlapping voices on both sides. Japanese chatter on one frequency, rising in pitch as they sighted him. American voices on another, bombers calling headings, someone screaming about taking fire.

Doctrine said: Disappear. Dive away. Lead them on a chase. Save the plane.

His eyes went to the Avengers again. Twelve blunt-nosed, rugged birds. Each one carrying a torpedo that could gut a transport ship. Each one crewed by three men who had woken up that morning and eaten powdered eggs and written quick letters and climbed into their cockpits believing the fighters upstairs had their backs.

He thought about his father under that crane. The way a cheap cable had snapped and three men had died because somebody had decided the system could handle just a little more stress.

He thought about Uncle Pat saying, “You think about the whole thing, Kenny, or you miss the part that kills you.”

It wasn’t just 36 men.

Those Avengers were heading for Japanese supply lines. Ships full of fuel, ammunition, food, reinforcements. Every ton of that cargo that reached its destination meant more Allied dead down the line. The math ran forward: bombers survive, ships sink, battles later are easier, men he would never meet live through campaigns they otherwise wouldn’t.

In a garage in Brooklyn, you misdiagnosed a bearing and you bought yourself a complaint and a bad reputation.

Up here, you misdiagnosed the system and you bought body bags.

“Sorry, Major Grace,” Walsh murmured. “Sorry, doctrine.”

He eased the throttle forward, feeling the engine’s response, trimming ahead of the torque already.

“Let’s dance,” he said.

The first Zero came out of his eleven o’clock high, what any instructor would have called a textbook bounce.

Walsh saw the glint, then the shape. Sleek, clean lines, rising sun on the wing. It dropped its nose and committed to the dive, cannon already twitching.

At 800 yards, the Zero opened up.

Walsh saw the winking of the guns, saw the tracer stream fling itself into the empty space where he would be if he continued straight and level.

He didn’t yank away.

He turned toward the Zero.

Not hard. Just enough. A twenty-degree bank, nose edging up, making his aircraft a little bit bigger in the Zero pilot’s windscreen. He knew what it looked like from the other cockpit: a crazy American willing to go for a head-on pass, turning his nose into a spear of guns.

A head-on at combined 600-plus miles per hour was madness. At that closure rate, they’d have barely a second to aim. One twitch. One mistake. Mutual kill.

Walsh had no intention of going through with it.

At 400 yards—half a football field in a fraction of a heartbeat—Walsh slammed the stick hard right and stomped right rudder.

The Corsair snapped.

Two thousand horsepower and heavy wings made for a roll rate that felt like somebody had grabbed the tail and flung it. Walsh felt the world spin in a blur of blue and silver: sky, ocean, Zero, sky again.

He came out of the roll on his side, nose pointed up, pulling hard.

The Gs hit him like a truck. His vision tunneled, gray curling in at the edges. He breathed like they’d taught him: short, sharp, tightening his legs to keep blood in his head.

Below, the Zero who’d been diving on him screamed through the space he’d vacated, overshooting, control surfaces biting into too-thin air at too-high speed.

At 300 knots, the Zero was a gymnast.

At 400-plus in a steep dive, it was a thrown brick, just like everything else.

Walsh’s Corsair, climbing, cut across the Zero’s projected path like a crossing guard stepping into traffic at exactly the right second.

He rolled at the top, bringing his nose down. The Zero flashed through his gunsight for a heartbeat.

Walsh squeezed the trigger.

Six Brownings barked. The aircraft shook with recoil. Tracers reached out, a bright, deadly thread.

He saw the right wing of the Zero rip apart in a spray of fragments. A puff of smoke. A sudden bloom of flame.

The Japanese plane rolled, so fast it had to be uncontrolled, and dropped toward the sea, trailing black.

Walsh didn’t watch it hit. He didn’t have time.

“Splash one,” he muttered, more to keep his brain organized than to boast.

Two more Zeros dove on him, nose down, wings shivering as they picked up speed.

He felt a kind of clarity he’d only ever experienced under a car with a wrench in his hand. The chaotic mess of threats resolved into vectors, speeds, altitudes. He wasn’t seeing planes; he was seeing energy states.

He didn’t try to turn tighter than they could. He let his engine work.

He rolled into them again, then climbed, always climbing, always trading speed for height at the last possible moment, forcing them to follow him into the vertical where their engines couldn’t keep up.

They tried to stay with him.

They stalled.

For a pilot trained to think of “maneuverability” as how tight you could carve a horizontal circle, it must have been infuriating—this American refusing to play their game, insisting on running the fight on a tilted axis where their hard-earned advantage vanished.

Walsh reversed, came down, fired.

Second Zero spiraled away, trailing fuel.

Third tried to break before he got into position, snapping right. Walsh was already rolling, anticipating the escape, like feeling a vibration in a steering wheel and knowing which bearing would fail.

He saw a brief flash of canopy. A helmet. Then his gun sight’s pipper slid across the Zero’s nose and he fired again.

The cockpit exploded in shattered glass and blood. The plane rolled, its pilot slumped.

Three kills in less than ninety seconds, and in front of him the blue was now full of red suns.

They were talking about him on the Japanese radios now.

He didn’t speak the language, but tone carried. He heard clipped words, rising in pitch, overlapping. Commands. Swears, probably. Someone laughing a little too high and a little too long. Nerves.

He didn’t have the luxury of enjoying that.

He checked his fuel. The needle sat at a number that left him a sour taste in his mouth. Fifteen minutes of hard flying left. Maybe twenty if he babied it. Then a long glide home or a short, fiery drop into the ocean.

“Stay away from the throttle,” his practical brain whispered. “Save what you can.”

“Those torpedo boys didn’t get that memo,” another voice shot back. “They’re still flying their profile like you’re up here doing your job.”

He looked down. The Avengers were dots now, five miles to the west and low, heading toward their run-in.

He turned his nose, keeping himself between the majority of the Zeros and the bombers like a man stepping between a gang and a friend.

Six Zeros came in from his six o’clock, line abreast, a textbook coordinated bounce.

Damn, he thought. They learn fast.

At 400 miles per hour, they’d eat him alive if he let them get in phase.

Walsh did something his instructors would’ve called suicidal.

He chopped his throttle.

From 350 knots, he pulled back to 280 in the space of a few seconds, nose coming up just enough to dig into the air. The Corsair groaned, but he kept her honest.

Behind him, the six Zeros were committed.

They were in the dive, engines screaming. They couldn’t bleed that much speed that fast without stalling or breaking something. They overshot. All six of them slid right past him, formation unraveling like a bad weld under stress.

For one beautiful moment, the sky in front of him was all enemy.

Walsh shoved the throttle back up. The Double Wasp roared in his ears, prop biting. The Corsair surged.

He picked the trailing Zero—the one with the least room to maneuver—and walked his tracers up from tail to cockpit.

The Zero became a fireball.

The remaining five broke in different directions, instincts screaming Get clear of this lunatic.

Walsh didn’t chase. He climbed again, always up, always thinking about the bombers and the time.

Every time he pointed his nose down to take a shot, he paid for it with fuel and altitude. He couldn’t afford to spend both chasing one or two kills. He had to think like an engineer triaging a failing system: fix the fault that will kill you first.

Right now, that fault was massed, coordinated attacks.

He saw them clustering again, smaller knots of Zeros trying to gather into a hammer to smash him flat.

He wouldn’t let them.

They came in from three directions at once—above, sides, below—a convergence of twenty fighters that should have been impossible to survive.

Walsh went for the biggest group.

He yanked the nose up and flew straight into the eight Zeros diving from in front and above, ignoring the ones on his flanks and low.

Eight against one.

Somewhere in a boardroom back in the States, men with maps and pointers would’ve marked this as “loss probability: 100%.”

At 800 yards he fired straight into the center of their formation.

He wasn’t trying to hit a specific plane. He was throwing a wrench into the gears.

Tracers slashed through the air. The lead Zero flinched, veering instinctively. The one to his right caught three rounds through the engine cowling and peeled away trailing smoke. The others reflexively jinked, their tight pattern unraveling under the simple, human urge not to fly into gunfire.

By the time they got their act together again, the perfect firing solution they’d built was gone. Now they were just eight planes in roughly the same sky, each pilot on his own.

Walsh rolled, stuffing the nose down and right toward one of the side groups. Same trick. Burst of fire into their path. Another scattering.

They were starting to fear him. He could feel it as much as see it.

Fear made people reactive. Reactive pilots gave initiative away. Initiative was energy in another form.

Walsh grabbed it with both hands.

Fifteen minutes.

That’s how long the whole mad engagement lasted, though if you’d asked Walsh later to guess, he’d have told you it felt like five seconds and five hours at the same time.

His muscles burned from constant G-loads. His eyes throbbed from scanning, scanning, scanning, never trusting any piece of sky for more than an instant.

He watched his ammo counters dwindle. Saw one gun go dry, then another, then another, adjusting his bursts to compensate, shortening them, conserving.

He smelled cordite constantly now, a bitter tang in the back of his throat.

He lost track of how many times he went vertical, how many times he rolled to get a shot and then broke away without taking it, refusing to give into the temptation to waste energy on a low-probability kill when his job was bigger.

He was aware of individual Zeros the way a man in a bar fight is aware of fists—fleetingly, in flashes of motion and impact—but the thing he was really fighting was their ability to concentrate.

Every time a Japanese pilot tried to assemble two or three wingmen into a coherent attack, Walsh appeared in their path like a ghost, guns flashed, smoke blossomed, formations shattered.

It wasn’t sustainable.

The fuel gauge was honest. The plane didn’t care how noble the mission was; when the tanks ran dry, it was a glider.

At 8:54, he looked at the clock on his panel and knew he had a choice: keep dancing until the music stopped or bug out now and pray the bombers had gotten through.

Then he heard the call.

“TBF formation to cover—uh, Corsair One-Five, you still with us out there?”

Static. Then another voice, calm, almost disbelieving.

“Avenger lead to any friendly—bombers are feet wet, egressing target. All aircraft accounted for. Appreciate the company, whoever you are.”

Walsh let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding.

Twelve bombers.

Thirty-six men.

Every one of them still talking, still flying.

He scanned the sky one more time. Counted.

Thirty-eight Zeros still in view. He’d flamed four for sure. He’d seen at least three more trailing smoke, damaged. Others might have been hit by their own mistakes, by collisions, by panic.

He flicked his radio to the squadron frequency.

“Marine One-Five to base,” he said, voice steady despite the adrenaline shaking his bones. “Lavella patrol complete. Bombers clear. Request vectors for home.”

The Zeros did not follow him when he turned for the dot on the horizon that was Munda Airfield.

They were low on fuel now themselves. Low on ammo. And maybe, just maybe, low on stomach for more of this particular brand of insanity.

Walsh landed at 9:27.

He rolled to a stop on the strip, engine idling, hands suddenly shaking so hard he had to grab the dash.

Ground crew swarmed the Corsair. Someone yanked his canopy open. Hot, humid air rushed in, carrying the smell of burned powder and jungle rot.

“How bad’d they get you, Lieutenant?” a mechanic called up to him.

Walsh blinked, as if he’d forgotten the plane had skin.

He climbed down and walked around the Corsair slowly.

Seven holes. Jagged, snapped metal, torn paint. Bullets had walked across the wings and the fuselage, searching for something vital. None had found it.

“Lucky,” someone muttered.

Walsh shook his head.

“Balanced,” he said softly.

He still had twenty-three rounds in his guns.

Twenty-three .50-caliber bullets.

The intelligence officer debriefed him for two hours in a hot tent, pencils scraping across paper as he tried, again and again, to explain it.

“Energy,” Walsh said. “It’s all energy. Speed, altitude—two sides of the same coin. The Corsair’s engine gives you more of it than the Zero has. If you spend it right, you never give them the kind of turning fight they want.”

“But fifty, Lieutenant?” the intel officer said, frustration fraying his tone. “You’re telling me you engaged fifty enemy aircraft alone for fifteen minutes and they never once pinned you?”

“They tried,” Walsh said. “I just didn’t let them do it on their terms.”

He talked about chopping throttle to make them overshoot, about driving into formations to break them, about firing at the group instead of individual planes to disrupt coordination. He talked about the vertical, about how the Zero lost its edge when it had to climb hard.

The intel officer’s notes went up the chain. Some colonel somewhere underlined the word “vertical” three times.

Other pilots came by his tent that night, some with awe in their eyes, some with skepticism.

“You really stayed in there with fifty?” one asked.

“Twelve Avengers,” Walsh said. “They had names, too. I just didn’t know them.”

On November 28th, 1943, in a ceremony that felt weirder than any dogfight, Kenneth Walsh received the Medal of Honor.

The citation used phrases like “extraordinary heroism” and “valiant devotion to duty.” It mentioned that he had “faced an overwhelming number of enemy fighters” and “continued to protect the bomber formation despite heavy odds.”

It did not mention torque.

It did not mention energy.

Medals were for courage, not for applied engineering.

But in ready rooms from the Solomons to the Marshalls, pilots talked less about the ribbon and more about the tactics.

“Don’t turn with a Zero,” they’d say, echoing doctrine. Then they’d add, “Go up. Make him bleed off speed. Make him climb into your guns.”

Walsh trained twenty-three pilots personally before he rotated home in March 1944. He didn’t have a formal syllabus. He had a stool, a chalkboard, and a Corsair out on the ramp.

He’d draw diagrams: circles for turning fights, arrows for climbs and dives, little triangles showing where energy increased or decreased. He’d write words like “POTENTIAL” and “KINETIC” and draw equals signs.

Then he’d take them up and show them.

“You feel that mush when you go too vertical in the Zero?” he’d say over the radio as they practiced mock fights. “That’s him running out of power. That’s your cue. You don’t chase him. You wait for him to stall, then you drop on him.”

Slowly, like oil seeping through a machine, his way of thinking spread.

The kill-to-loss ratio for Marine Corsair squadrons changed. In early 1943, it was ugly—one Corsair lost for every 1.3 Japanese planes shot down. By late 1944, that number had flipped on its head and grown fangs. Eleven-to-one. Eight-to-one. Numbers that made planners blink.

Some of that was better hardware—improved canopies, clearer sight lines, minor fixes. Some of it was experience. But in squadron bar stories, a lot of it tracked back to “that crazy mechanic from Brooklyn who went up against fifty and lived.”

Japanese pilots noticed, too.

Intercepted radio traffic from late ’43 had new notes: warnings about Corsairs that climbed instead of turned, curses about Americans who refused to get into the kind of dances the Zero loved.

By mid-1944, smart Zero pilots picked on Wildcats and Hellcats when they could.

A Corsair flown by a Marine who understood Walsh’s lessons was a bad bet.

Some analyst years later—safe behind a desk, with stacks of after-action reports and loss charts—ran the numbers.

He looked at the bombers that survived that August 15th mission. Looked at the supplies they destroyed. Looked at the ground units that didn’t get those supplies, the battles that broke differently because of it. Looked at the Marine pilots who came home because they’d learned to fly in the vertical.

He wrote a line in a report that would never be read by the men who’d made it true:

Estimated Allied lives preserved directly and indirectly by Walsh’s actions and subsequent tactical innovations: in excess of 1,000.

A round number. An approximation. But every digit in it stood on a real man’s heartbeat.

Walsh stayed in the Marine Corps after the war.

He flew F9F Panthers over Korea, jets this time, no prop torque, different envelope. But the physics hadn’t changed. Speed was still energy. Altitude still a bank. He taught a new generation how to think in three dimensions while others were content with two.

He retired as a colonel in 1962. Two wars. 473 combat missions. Twenty-one confirmed kills. Fifty-three more probables and damaged.

Numbers, again. Engineering without context.

He died on March 30th, 1998. Heart failure at eighty-one.

At Arlington, under a sky that looked very different from the one over Vella Lavella but obeyed the same rules, more than two hundred Marine aviators came to see him off.

Some of them had flown with him. Old men now, stooped, their own hearts ticking toward final approach. Some were younger, hair still regulation short, g-suits still hanging in lockers at Miramar and Beaufort and Cherry Point.

They’d all climbed into cockpits at some point and rolled inverted and pulled down through a maneuver that felt like it might rip their wings off, and somewhere in the back of their minds they’d heard a voice:

The plane’s a system. Balance it before it bites you.

At the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Quantico, tucked under the sweep of a glass-and-steel wing that echoes a Corsair’s bent smile, there’s a photograph of a young man standing beside a dark blue fighter.

The aircraft number on the landing gear door reads 15.

Four small Japanese flags are painted under the canopy.

The plaque says:

First Lieutenant Kenneth A. Walsh, Medal of Honor recipient, engaged 50 Japanese fighters alone over Vella Lavella on 15 August 1943, protecting a bomber formation from destruction.

It does not mention Brooklyn.

It does not mention an uncle with grease on his hands explaining how torque walks through a system.

It does not mention a young Marine sitting in a hot cockpit over Pensacola, realizing that if you stop fighting your machine and start understanding it, it will take you places no doctrine ever dreamed of.

But if you stand there long enough, watching the way the light reflects off the bent wings in the photograph, you might start to see what he saw on that morning over Vella Lavella:

Lines and arcs.

Speed and height.

Inputs and outputs.

One man and one machine, balancing a system gone mad just long enough to keep a thousand other hearts beating.

Not bad for a mechanic.

THE END

News

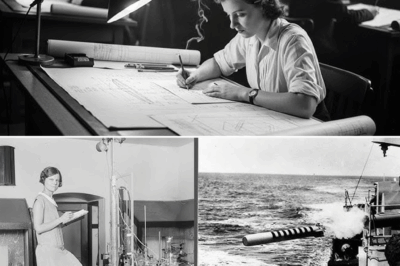

CH2 – The Female Engineer Who Saved 500 Ships With One Line of Code

By the winter of 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic sounded like a broken heartbeat. Convoys vanished off the map…

CH2 – Paralyzed German Women POWs Were Shocked By the British Soldiers’ Treatment…

On a desolate stretch of road in northern Germany, in the wet, uncertain spring of 1945, a convoy of British…

CH2 – How One Crewman’s “Mad” Rigging Let One B-17 Fly Home With Half Its Tail Blown Off

At 20,000 feet above the Tunisian desert, the tail of All-American started to walk away. Tail gunner Sam Sarpalus felt…

CH2 – German Sniper’s Dog Refused to Leave His Injured Master — Americans Saved Him…

The German Shepherd would not stop pulling at the American sergeant’s sleeve. It had started subtle: a tug at the…

CH2 – The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men

The German officer’s boots were too clean for this part of France. He picked his way up the muddy slope…

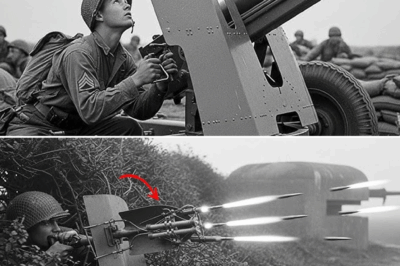

CH2 – This 19-Year-Old Was Manning His First AA Gun — And Accidentally Saved Two Battalions

The night wrapped itself around Bastogne like a fist. It was January 17th, 1945, 0320 hours, and the world, as…

End of content

No more pages to load