At 9:23 a.m. on March 25, 1941, nineteen-year-old Maggie Batty stared at a sheet of encrypted Italian naval traffic and thought, If I screw this up, people are going to die—and one of them might be my brother.

The clock on the wall of the converted Virginia farmhouse ticked too loudly. It always did when a new intercept came in. The office was cold enough for her to see her breath; the radiators along the baseboards clanged and hissed but never quite got around to heating anything. Outside, the muddy yard of “Station Liberty” was full of uniformed kids not much older than she was, ducking from one clapboard building to another under low gray clouds. Inside, the “cottage”—a drafty wing of the big house that still smelled faintly of hay and horse—was full of failure.

Failure in neat manila folders. Failure in pigeonholes and file cabinets. Failure in the metal baskets stacked floor-to-ceiling along the wall behind her: hundreds of Italian Navy Enigma messages, every one of them still just random five-letter groups. Every one of them a blindfold tied over the eyes of Allied ships in the Mediterranean.

Maggie flexed her freezing fingers and pulled the latest sheet closer.

CALL SIGN: XYZ14

ORIGIN: SUPERMARINA, ROME

ADDRESSEE: FLAGSHIP VITTORIO VENETO

TIME: 0847/25 MAR 41

Then, line after line of near-meaningless blocks:

SQPPB NQUGF ZSLIO …

One more message from a Navy they couldn’t read. One more letter to the bottomless pile.

Except this time, the fear sitting in the back of her skull had a specific face: her brother Jeff’s.

Jeff Batty, twenty-three, Lieutenant (junior grade), United States Navy. Communications officer attached to a British heavy cruiser running convoy duty in the Mediterranean. He’d joined up the moment Europe caught fire. He’d written home about blue water, white caps, and Italian submarines that wouldn’t stop coming. His letters were all jokes and doodles and exaggerated tales, right up until the one that had arrived in their parents’ Cleveland mailbox a week ago.

They’ve got us half-blind out here, Mags.

No one knows where the big Italian ships are. It’s like playing chicken on a highway with the headlights off. Don’t worry Mom and Dad with that—just you. I know you wanted to “do your bit” with codes or whatever. If you ever get a chance to help in this theater… take it. We kinda need it.

She’d read that line three times, then folded the letter back along its creases and slid it under her pillow in the women’s bunk room here at Station Liberty.

Three days from now—March 28—Jeff’s convoy was scheduled to leave Malta, loaded with British and American fuel and ammunition bound for Egypt. Nobody at this station was supposed to know that, but intelligence was a leaky ship; you picked things up. That convoy was a fat, slow bullseye.

If the Italians knew about it, they’d send everything they had.

And Maggie was supposed to help make sure they didn’t.

She pushed Jeff out of her mind and focused on the sheet. Letters only. Just letters. People’s lives were math now: rotors and plugboard pairs and probabilities.

“Batty.” A dry voice floated across the room. “You talking to the paper again?”

She looked up. Professor Dylan Knox—always “Doc” or “Dilly” behind his back—stood in the doorway to his tiny office, mug of black coffee steaming between his fingers. He was fifty-six, looked seventy, and walked like each step hurt. He was wearing the same threadbare brown suit he’d worn yesterday, and the day before that, and probably back when Woodrow Wilson was still President. The suit smelled faintly of pipe smoke and chalk dust.

“You’re muttering,” he said, in his faint Boston accent. “Especially bad when the subject can’t mutter back. Drives the rest of us around the bend.”

“Sorry, sir,” Maggie said.

He shuffled closer, peered at the page through his thick rimless glasses, then at the growing mound of similar pages on her desk.

“How many Italian naval intercepts on your stack now?”

“Counting this one? I think… two hundred and three, sir.”

“And we have successfully read…”

“Zero,” Maggie said.

“Ah yes. My favorite number.” His mouth twisted into something that flirted with a smile. “Carry on.”

He turned to go back into his office, then paused. “But don’t be afraid to offend the machine a little.”

“Offend it, sir?”

He tap-tapped the paper with a yellowed fingernail. “The boys over in Washington say this thing is mathematically unbreakable. They love that word. ‘Unbreakable.’ Very clean. Very modern.” He shrugged. “Mathematics describes what’s possible. Humans decide what actually happens. We’re not at war with Enigma, Miss Batty. We’re at war with the men who use it. And men are lazy, prideful, scared, horny, bored. All the things math is not.”

His eyes twinkled for a moment. “So look for bad habits. That’s where the cracks start.”

She nodded. He shuffled back into his office, shutting the door against the cold.

Maggie lowered her eyes to the message again.

Mathematics versus human laziness. Fine. Great. Except she wasn’t a mathematician, and human laziness had stubbornly refused to show up for the last six months.

She’d been at Station Liberty for exactly half a year. Six months since she’d walked away from University College London—where she’d been studying abroad when the war broke out—and then from college entirely when she came home to the States. Six months since a gray-haired man from the War Department had pulled her aside after a language exam and asked, very politely, if she could keep secrets.

“This is a quiet war,” he’d said. “Someone has to fight the part that doesn’t make the newspapers.”

And here she was. One of the youngest members of the U.S. Navy’s hush-hush code and cipher section, buried in a former horse farm in rural Virginia, being told to break a code that everyone called impossible.

Enigma. Three rotors, each with twenty-six positions, cycling with every keypress. A ring setting for each rotor. A plugboard that swapped pairs of letters in front of and behind the rotor maze. Change all of that every twenty-four hours. Multiply the combinations. Get a number so big it made her head hurt: 10 to the 23rd, roughly.

One hundred and fifty-nine quintillion possible daily keys.

British mathematicians in their manor houses had been chewing on German Enigma for years. They’d built machines to hammer through keyspace. They’d turned cribs and known phrases into footholds. They’d had some success. But the Italians?

The Italian naval Enigma, the variant used by the Supermarina and the battle fleet, had beaten them cold.

Nineteen months of nothing.

Until this cold March morning in Virginia, when one overworked Italian radio operator in Rome made a mistake.

The first thing Maggie did with any new message was mechanical: count things.

She took a pencil, tapped the eraser twice against the pad of her left thumb, and started marking the page. Line by line, she made tiny ticks in the margins for each occurrence of A, B, C, all the way to Z. Encrypted text from a good machine with good procedures should look like static—nothing but noise in every direction. But humans never quite managed perfect randomness. Certain letters loved to clump together; certain bigrams showed up too often.

You could never tell which of that was the machine and which was the man.

Twenty-seven minutes of counting later, she frowned.

The pattern wasn’t in the counts. It was in the page itself.

Five-letter groups marched across the paper in double-spaced lines. Her eye snagged on one in the third line:

SQPPBN

There was something about the way the letters sat together. The repetition of the P, that B that felt like a hinge. She’d seen that group before. Not today. In the pile.

She scanned downward.

There. Fourth line from the bottom.

SQPPBN

Same group. Exact match. Same ordering, same everything.

Her heart banged once, hard.

That wasn’t supposed to happen.

Every time you hit a key on an Enigma machine, the rotors stepped. Type the same letter twice in a row, you didn’t get the same ciphertext letter twice; the internal wiring changed between keystrokes. That was the point. That was why every mathematician on both sides of the Atlantic walked around calling the thing “unbreakable.”

The odds that the same six-letter plaintext chunk, encrypted at two different points in a message, with the rotors in two different positions, would reduce to the same six-letter ciphertext chunk were… what? A billion to one? Ten billion?

Unless.

Unless it wasn’t random at all. Unless the same six-letter plaintext sequence had been typed in two places where the guts of the machine happened to have rotated into the same pattern.

Highly unlikely. Not impossible.

And if it weren’t random, if it were the same exact Italian word typed by some bored, rushed, possibly lazy radio operator, then the machine’s big scary space of 159 quintillion keys suddenly had a human fingerprint pressed into it.

Maggie leaned back, closed her eyes for a moment, and heard Doc Knox’s voice in the back of her head.

We’re not chasing the machine. We’re chasing the man.

What would the man have done?

She opened her eyes and stared at the two copies of SQPPBN. One at position forty-seven in the message. One at eighty-seven. Forty characters apart.

Radio operators padded short messages. Standard practice. You never sent a message that said something as nakedly useful to the enemy as “Fleet here, going there, at this time.” You bolted nonsense to the front and back. Useless flourishes. Fillers. Words that meant nothing so that the important stuff disappeared inside like raisins in a loaf.

The filler was supposed to be different every time.

Supposed to be.

Maggie pulled open the top drawer of her desk and flipped through her notes until she found the scrap she wanted: Doc Knox’s messy handwriting, scribbled during a lecture weeks ago.

ITALIAN PADDING HABITS

— “PER X” / “PERXXX” — VERY COMMON

— “NONSENSO”

— RANDOMIZED CITY NAMES

He’d circled PERXXX three times. Per X. For X. To X. A dozen possible insignificant uses.

He’d said, offhand, “If some Italian petty officer ever decides his life is short enough already, he’ll use that same lazy padding twice in a row. And when he does, I want one of you to catch it.”

Maggie set the scrap next to the intercept.

Six letters.

PERXXX would be seven counting the space.

But an operator in a hurry, one thumb pressed to a cigarette, might jam on something like PERPER, or PERTUT, or a meaningless fiction that still started with that basic stem. Or maybe the sense was reversed. Maybe the filler was something like NAVNAV, or MAREMA, or some shorthand she didn’t know.

Either way, if SQPPBN mapped to the same six-letter Italian plaintext block in both places, she had what cryptanalysts called a “crib.”

A guess.

A crazy one.

Her pulse picked up. Her pencil tapped faster against her thumb.

All she had to do was turn that crazy crib into a full set of rotor and plugboard settings for March 25, 1941.

In the next… what? Forty-eight hours? Seventy-two? Before the Italians changed keys again and this whole thing reduced back down to static?

Before Jeff’s convoy sailed.

The door to the cottage banged open.

Cold air swept in along with Commander James Bradshaw, U.S. Navy, on loan from Intelligence for the sole purpose of making sure nobody in the cottage did anything too interesting without permission.

He always looked out of place here. Too crisp. Too regulation. His hair actually obeyed his hat, which offended Maggie on some deep level.

“Knox,” he called. “You got a minute?”

Doc’s office door opened. He stepped out, coffee still in hand. “I can give you two. After that the mind rebels.”

The commander’s eyes swept the room, taking in the stacks of Italian intercepts, the chalkboard full of rotor diagrams, the seedy collection of tired young analysts.

His jaw tightened.

“In private,” Bradshaw said.

The door shut behind them.

Maggie scooted her chair back half an inch so she could hear. The cottage’s walls were thin; sound seeped right through.

“This section was told to stand down on Italian naval work a month ago,” Bradshaw said quietly but sharply. “Those orders came from very high up, Professor.”

“And yet the Italian Navy continues to exist,” Doc replied dryly. “A mystery for the ages.”

“We don’t have the manpower to waste on something all the experts say is impossible.”

“Experts. You mean the nice boys with the degrees from Princeton who already decided they don’t like being wrong.”

Bradshaw’s voice cooled another ten degrees. “You’ve got until oh-eight-hundred tomorrow to show me something. Anything. Otherwise I am shutting this whole little hobby shop down and sending your people where they’ll be useful.”

Silence for a beat.

“Very well,” Knox said.

The office door opened. Bradshaw came out, stepped past Maggie’s desk without a glance, and left the cottage.

Doc lingered in the doorway, looking older than he had an hour ago.

Maggie swallowed. “Sir?”

He checked his battered watch. “We have… twenty-two hours and thirty-three minutes before the good Commander swings his axe. Give or take.” He looked directly at her. “You have something better than zero for me by then?”

Her mouth went dry.

She turned the page so he could see the twin SQPPBN groups. “I think so, sir.”

He leaned in. Saw them immediately. His eyebrows rose a millimeter.

“Interesting,” he said.

“They’re forty characters apart,” she said quickly. “Same six-letter group. Statistically that’s—”

“Strange,” he finished. “Which means someone got lazy.”

He shuffled to her other side, picked up the scrap about padding habits, and squinted at it. “You’re thinking filler word?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Any candidates?”

“Not yet. But if I assume it’s the same word in both places, I might be able to work backwards through the rotors. If I can align where the machine would have been for the second occurrence with where it was for the first, I can… walk the difference, I guess. See which rotor settings would make that possible.”

Maggie heard how insane it sounded as she said it out loud.

Doc Knox’s eyes didn’t leave the page. “You know we’re not supposed to be working on this traffic at all.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You know if you’re wrong, the brass will have confirmation they need to call this a waste of time. They will shut us down. You’ll be lucky to be sorting weather reports in Omaha for the rest of the war.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You know if you’re right, but you can’t prove it by tomorrow morning, they’ll call it a fluke anyway. And they’ll still shut us down.”

She held his gaze. “Yes, sir.”

He studied her for a long moment. Then—slowly—he smiled.

The first real smile she’d seen from him in weeks.

“Well,” he said softly. “Then I suppose there’s only one thing to say.”

“What, sir?”

He tapped the ciphertext.

“Prove it works.”

From noon to sundown, the cottage ceased to be a room and became a lighthouse with a single beam aimed at the space between two six-letter groups.

Maggie barely moved from her chair.

She transcribed the message cleanly into her notebook, marking where each letter fell in the sequence. She labeled the positions of SQPPBN as i through i+5, and j through j+5, then worked out how many rotor steps apart they had to be. Forty letters in the ciphertext didn’t necessarily equal forty steps on the rotors—because of how the machine advanced—but she could bracket the possibilities.

She sketched the wiring sequences of the three rotors they knew the Italians favored. Rotor I, II, III. Then all the possible orders they could be in. Then she started doing what the math boys said was pointless.

She guessed.

Not in the way they meant. Not blind throws into a quintillion-sized void. This was a hunter’s guess. Her father used to take her and Jeff to an overgrown lot outside Cleveland to watch freight trains hauling ore. You couldn’t see the whole train at once, but if you saw a red boxcar and knew the order of the cars was mostly fixed, you could make a good guess where the second red one would show up if they were both on the same line.

Same theory.

If SQPPBN was the same Italian word twice—padding, some standard nothing phrase—then the Enigma machine must have been in two states that, run against the same six plaintext letters, produced the same six ciphertext letters. That put constraints on how the current ran through the rotors.

Some rotor starting positions wouldn’t allow it. Some plugboard wirings would make it impossible. She began eliminating them, scribbling lines through combinations in her notebook, flipping pages when she filled each one.

By three p.m., her head was pounding.

By four, sunlight had faded to gray at the cottage windows and the radiators had given up entirely.

By five, her fingers were cramped into a permanent claw around the pencil.

The only breaks she took were to run to the bathroom and splash cold water on her face. She ignored the sandwich one of the other girls tried to slide onto her desk. Her stomach had closed itself off, declared independence.

At some point, a pair of Marine guards trundled a heavy safe into Knox’s office. The cottage went quiet while they spun the dial and signed the log.

Inside that safe was the only piece of physical machinery that mattered more to her right now than the beating of her own heart: a captured Italian naval Enigma, salvaged by the British from a snagged submarine and shipped to the States under guard.

The machine was their oracle.

If she found a key, it could tell her whether she was a genius or a fraud.

At six-thirty in the evening, with the light outside almost gone, Maggie stared at a single line in her notebook. All the others were crossed out. This one was not.

Rotor order: II-III-I

Ring settings: 04-17-22

Starting positions: G-Q-L

Plugboard pairs: (A-T) (B-M) (C-R) (E-L) (G-H) (N-P) (O-S) (Q-V) (W-Z) (Y-J)

If she treated the plaintext behind SQPPBN as PERXXX—“PERXxx”—with the last three letters floating, this configuration made the wiring work out. The double P’s mapped to double letters in positions that couldn’t have been produced otherwise. The internal logic of the rotors held.

“Internal logic.” She almost laughed. She was inventing phrases now.

Her pencil hovered over the page. This is crazy. A voice that sounded suspiciously like her mother’s piped in. You dropped out of college, Margaret. You are nineteen. You are trying to out-compute a machine and two continents of experts.

Then she thought of Jeff’s letter, of the offhand line about headlight-off highway chicken.

What did he write, when he was that scared? Who did he write to?

Her.

She stood up on legs that didn’t feel attached and walked to Knox’s office. Her knuckles rapped once on the doorframe, more out of habit than intention.

“Come,” he said.

She stepped in. The office contained one battered oak desk, one chair that looked old when Teddy Roosevelt was President, and enough cigarette smoke to kill a small animal. Maps of the Mediterranean and North Africa were taped to the walls, complete with pins and colored string.

Doc looked up from his notes and watched her come in. His eyes flicked to her notebook.

“Well?”

“I’ve got something,” she said, voice rough.

“Mathematically perfect or intuitively offensive?”

“A little of both,” she admitted. “But I think it might be the daily key.”

He held out his hand.

She gave him the notebook.

He skimmed her elimination work with a speed that made her brain hurt. He didn’t question her every step. That was the scariest part. If he’d challenged her at every line, she could have shrugged and said I tried. Instead he nodded occasionally, as if each insane leap made a dangerous kind of sense.

At the key block, he stopped. His mouth twitched.

“Per X,” he said.

“Assuming, sir,” she said quickly, “that the Italians reused some form of that padding twice.”

“A crazy assumption,” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

He closed the notebook and pushed back his chair. “Let’s light the candles then.”

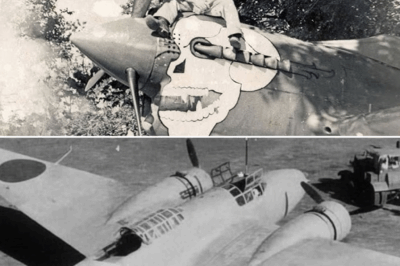

From the safe, he drew the Enigma machine: black metal case, hinged wooden lid, keyboard with stark white letters. It was ugly, in the way a spider is ugly. Too many legs, too many shiny parts, a functional malice.

He set it on the desk between them, its surface worn where other desperate fingers had once rested.

“You set the rotors,” he said quietly. “It’s your beast.”

Her hands shook as she took the machine’s rotors out and arranged them: II, III, I, in the order she’d written. She slotted them onto the spindle, watching the tiny notches align. She turned the rings to 04, 17, 22. GQL in the windows. She flipped open the plugboard and wired the pairs with black patch cables: A to T, B to M, and so on.

When she finished, she sat back. The machine looked exactly the same.

“That’s the thing about the universe,” Doc said dryly. “More fragile than it looks. One flipped bit here, one typo there, everything changes.”

He slid the plaintext/ciphertext sheet toward her.

“We’ll start with your SQPPBN,” he said. “See if we get anything that looks like Italian. Ready?”

No, she thought.

“Yes,” she said.

She set her fingers on the keys and typed S, Q, P, P, B, N.

The machine clacked and whirred. Six lamps lit up, one after the other, tiny spotlights in the gloom.

P. E. R. Q. U. E.

She stared.

P E R Q U E.

Perque. Because.

Italian. A real word.

She looked up at Doc. His eyes were bright.

“Continue,” he said.

She rolled the rotors back to GQL. Took a breath. Fed the entire message through, letter by letter. The machine chattered like a possessed typewriter. The lamps winked. She scribbled the outputs in her notebook without letting herself translate.

When it was done, her hand ached and the room buzzed with a stunned silence.

Doc reached for the notebook, read the first full line of decoded text, and let out a sound somewhere between a laugh and a groan.

“What is it?” she asked, throat tight.

He read aloud, in a rusty approximation of Italian, then translated as he went.

“Fleet… attack… scheduled… Crete… twenty-seven March.”

Her pulse roared in her ears.

He flipped the page. Another message, same day, same key. Bulk orders about fleet dispositions, fuel states, air cover. Rendezvous points.

They had it. The Italians’ daily key. The whole plan.

Doc Knox sat slowly back in his chair, notebook still in his hands, like a man holding a live grenade that had decided, inexplicably, not to go off.

“What you just did,” he said softly, “you understand what it means?”

“Does it mean Jeff’s convoy doesn’t have to sail blind?” she asked.

He studied her for one long second, then nodded once.

“Yes,” he said. “Yes, it does.”

The cable to Washington went out ten minutes later.

Knox locked the Enigma machine back in the safe and signed the log with a hand that didn’t quite tremble. Maggie hovered by the door while he phoned the secure line.

“Commander Bradshaw?” he said when the operator patched him through. “Yes, it’s Knox. I have your ‘something.’ Italian naval Enigma key for twenty-five March. Yes, I’m sure. Because I’m reading their mail.”

A pause. Maggie could practically hear Bradshaw’s stiff posture relaxing through the line.

“I need this passed to the British Mediterranean Fleet at once,” Knox said. “Priority Ultra. Yes, Ultra. We have details of a planned major Italian sortie near Crete on the twenty-seventh. And Commander? I will require my ‘hobby shop’ to remain open a little while longer.”

He hung up. He didn’t look triumphant. He looked tired.

“What happens now?” Maggie asked.

“Now,” he said, “we see what the British do with a crystal ball.”

Half a world away, in Alexandria, Egypt, Admiral Andrew Cunningham—the Royal Navy’s hard-jawed, American-born commander in the Mediterranean—read the decoded Italian messages twice.

His staff watched his face as he scanned the lines.

Three heavy cruisers. Two destroyers. One battleship, Vittorio Veneto. A powerful Italian battle group sailing from Taranto to intercept British convoys south of Crete on March 27. Departure time. Course. Planned rendezvous points. Air cover details.

Everything.

If those messages were genuine—and Ultra intelligence had been right too many times to doubt now—the Supermarina had just handed him their throat.

“Gentlemen,” Cunningham said, “they think they’re setting a trap.”

He folded the message.

“Let’s show them how it feels.”

Maggie didn’t sleep the night of March 26. She and the rest of the “Italian cell” at Station Liberty worked in shifts, running every new intercept they got through the key she’d found, checking for signs the Italians suspected anything.

They didn’t.

The next day, March 27, they kept doing the same thing. Each new message was a fresh drip of gasoline onto a fire only they could see.

She watched the pins on the cottage’s Mediterranean map shuffle, as reports came in—British aircraft sightings, Italian position checks, fuel state updates—filtered and delayed by hours, compressed into colored wool and tiny flags.

On the map, everything looked small.

In her head, when she pictured it, the scale exploded.

Out there were ships the size of skyscrapers lying on their sides. Thousands of men in steel corridors and cramped bunks. Above them, the weight of the sea. Between them and death, a few inches of plate armor and the assumption that their messages were unread.

At four in the afternoon, a liaison ran in from the radio room holding a flimsy marked MOST SECRET. His breath puffed in front of his face; he’d sprinted from the other building.

“From British Med Fleet HQ,” he said, handing it to Knox. “Time-lagged. Reporting Italian battle group departing Taranto. Eighteen hundred hours local. Looks like your friend in Rome was telling the truth.”

Knox read it, nodded curtly, and pinned a marker on the map near the heel of Italy’s boot. “There,” he said.

He picked up another marker and placed it off Crete. “Convoy route.”

Then, slowly, he positioned three small blue pins farther south and east—battleships, an aircraft carrier, cruisers, destroyers. Cunningham’s force.

“You want to know the funny thing, Miss Batty?” he said.

“Sir?”

“If you stand far enough back, they all look the same size.”

She stared at the little blue and red dots so hard her eyes burned.

“Do we know… how it ends?” she asked.

“We know where they’re going to be,” he said. “We know Cunningham likes to play his cards close. We know we read Italian mail, and they do not read ours.” He tapped the British pins. “But battles are decided in a very local way. By the man looking through the periscope. By the captain who decides to turn left instead of right. By the gunner who flinches at the wrong time.”

He shrugged. “Sometimes by a petty officer padding his messages with lazy little words.”

He didn’t say what she was thinking: And by a nineteen-year-old girl having a crazy hunch in a cold room in Virginia.

They didn’t hear about Cunningham’s golf game in Alexandria until later, in a wry summary from the British.

On paper, it sounded like something out of a movie.

On the afternoon of March 27, while Italian spies watched the harbor and reported that the British fleet was still at anchor, Cunningham dressed in casual clothes and went to the club. He played a slow, very public round of golf. He waved to acquaintances. He made sure to be seen.

Only when the sun dropped and the Italian agents saw him heading home, seemingly for a quiet night ashore, did the real show begin.

Cunningham’s crew had been quietly making their preparations for forty-eight hours. Ammunition loaded, engines hot, crews at their stations. As soon as darkness fell, they eased out of harbor under radio silence. Three battleships: Warspite, Valiant, and Barham. One aircraft carrier, Formidable. Four light cruisers. Thirteen destroyers.

Everything the Royal Navy had in that theater.

They slipped into the Mediterranean night, their wakes hidden, their radar sets sweeping blackness the Italians couldn’t see.

The Italians thought they were the hunters.

They were sailing into an ambush planned by someone who had read their playbook three days in advance.

The next day, March 28, the cottage became a strange halfway place: half radio shack, half altar. Everyone spoke in low voices, as if the wrong word might jinx a fleet half the world away.

British reconnaissance planes spotted the Italian force south of Crete that morning. Maggie read the sanitized version of that contact report while she chewed stale coffee cake and tried not to throw up.

At ten-thirty a.m., the Formidable launched a strike: Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers, slow and vulnerable, flying low over the waves under flak that turned the sky into a black confetti of death. Maggie tried not to picture the pilots’ faces. They weren’t much older than she was.

One of those torpedoes slammed into Vittorio Veneto’s port side at 15:19 hours, just aft of the engine room. The impact tore a thirty-foot hole in the hull. Seawater rushed in, flooding boiler rooms. The battleship’s speed dropped from twenty-eight knots to twelve. She wasn’t dead, but she was hurt badly, a prize buck suddenly limping.

The Italian admiral, Angelo Iachino, ordered the cruisers to shelter his flagship. The whole force turned away from the British and ran northwest, toward home.

Out of context, that might have worked.

The thing about Ultra was that there was no out of context. Cunningham knew exactly where they’d turn. He slid his battleships and cruisers on parallel courses like chess pieces, placing them squarely between the Italians and Taranto.

When Formidable’s second wave damaged the heavy cruiser Pola so badly her engines died, Iachino faced a choice. Leave seven hundred and fifty men stranded on a dead ship in waters you knew your enemy was hunting? Or send help?

He chose the human thing. He detached the heavy cruisers Zara and Fiume, along with the destroyers Alfieri and Carducci, ordering them back to tow Pola to safety.

Five ships. Five future wrecks.

From Station Liberty’s perspective, it all appeared as terse lines on paper.

Pola engines disabled, position grid reference X.

Zara, Fiume, Alfieri, Carducci detach for assistance.

Maggie traced the movements on the map with her fingertip, feeling chill.

“That’s them,” she said softly.

Knox nodded.

“The five,” he said.

Night fell over the Mediterranean like a curtain coming down.

On one side: the crippled Pola, listing slightly, crew huddled on deck in the dark, waiting for their sister ships to arrive.

On the other: Cunningham’s battle line, three gray giants sliding through the water with their lights out, radar sets cutting through the dark three times further than human eyes.

Between them: a patch of black ocean that was about to become hell.

Shortly before eleven p.m. local time—22:27 to be precise—British destroyers on the edge of Cunningham’s formation picked up radar contacts: ships approaching the stationary blip that was Pola.

They turned toward the unknown targets, closed in, peering into the night. The Italians had no radar. They saw nothing.

Then all three British battleships eased into position, broadside to the oncoming cruisers, just 3,800 yards away.

Point-blank range for fifteen-inch guns.

On Warspite’s bridge, an American liaison officer—Lieutenant Jack “Tex” Harding, on exchange duty—later said it felt “like standing in a movie theater before the reel starts, waiting for the projector to kick over.”

“Can you see them?” Cunningham asked his gunnery officer.

“Yes, sir,” the man replied. “They’re right where the Yanks said they’d be.”

Cunningham checked his watch. 22:28.

“Turn on the lights,” he said.

In the cottage, no one heard the thunder of the actual guns. But when the British summary came through forty-eight hours later, Maggie relived it in her head so vividly she swore she could smell saltwater and cordite.

On Cunningham’s order, the battleships’ searchlights flicked on simultaneously. Beams of stark white light knifed out across the dark, stabbing the night until they found metal. They splashed over Zara and Fiume like divine judgment, lighting hulls and superstructures, rails and gun turrets, every rivet picked out in merciless detail.

For three heartbeats, the Italian crews froze.

They’d been sailing in blackness, alone with the stars and their own breathing. Now they were standing naked in a ring of light, unable to see anything past the glare.

Then the world blew apart.

Warspite fired first. Eight fifteen-inch guns spoke with one voice, belching flame and smoke, hurling 1,920-pound armor-piercing shells across two miles of water.

At that range, missing was nearly physically impossible.

Three shells slammed into Fiume’s midships, punching through her armor belt, detonating deep inside. Internal bulkheads shredded. Ammunition lockers went up. A flash fire raced through passages. Men died without ever understanding what had hit them.

Moments later, Valiant and Barham opened up on Zara. Eight shells smashed into her forward superstructure and bridge. The ship’s commanding officer died instantly, nearly vaporized. In the engine rooms, scalding steam and shrapnel turned the compartments into ovens.

Italian gun crews tried to respond. Blinded by searchlight glare, seeing only white, they fired where they thought the enemy had to be. Their shells screamed into the dark, falling harmlessly hundreds of yards short or long, splashing tall geysers in empty water.

The British kept firing. Methodical. Every thirty seconds, another salvo. The glow from the guns strobed across the water, an obscene fireworks show no one had bought a ticket for.

On the cottage map, those shells were invisible. But Maggie read the after-action numbers: one hundred thirteen fifteen-inch rounds fired at Zara, with roughly eighty percent hitting. That kind of accuracy would have sounded made-up in a war movie.

It was very real when you had radar, prior knowledge, and two miles of distance.

At midnight, with both heavy cruisers burning and sagging in the water, Cunningham ordered his destroyers to finish off the cripples and the two escorts. Torpedoes arrowed through the dark. Alfieri broke in half and sank within four minutes. Carducci took three hits and exploded, a column of flame and smoke visible for miles.

Farther off, still helpless, still dead in the water, the crew of Pola watched the sky light up and heard distant thunder and didn’t know whose funeral they were hearing.

By four a.m., British destroyers had pulled alongside Pola. Boarded her. Found a crew shocked into near-catatonia. The British ordered them into boats, took about two hundred fifty prisoners, then fired torpedoes into the abandoned hull.

Pola slipped under at 04:10, stern first.

Five warships gone in one night: three heavy cruisers, two destroyers.

Casualties would never be known with exact, ledger-book precision, but the estimates settled around 2,303 Italian sailors lost—drowned, burned, or blown apart in steel rooms turned into coffins.

British losses?

One aircraft and its three-man crew, lost in the earlier airstrike.

Three to 2,303.

On paper, it looked like a mistake in the accounting. In reality, it was what happened when perfect surprise collided with industrial-scale firepower.

All because one Italian petty officer had reused a lazy filler phrase.

All because one American girl in a cold Virginia farmhouse had been stubborn enough to notice.

They didn’t tell Maggie the casualty numbers right away.

Someone higher up had decided the raw figures weren’t good for the analysts’ sleep schedules. As if anyone slept, anyway.

What they told her first was simpler: The battle group had been shattered. The Italian Navy had retreated into harbor, rattled and bloodied, and wouldn’t sortie in strength again for a very long time. The Mediterranean balance had tipped.

Oh, and Jeff’s convoy?

She got that update in the form of a typewritten slip slid under her coffee mug three mornings later.

CONVOY MW-6 ARRIVED ALEXANDRIA UNHARMED 02 APR 41. NO SHIPS LOST. BATTY, LT(JG) J., REPORTED AMONG PERSONNEL DISEMBARKED.

She stared at the words until they blurred, then set the mug aside and pressed the paper flat with both hands.

Jeff was alive.

He’d sailed through waters that could easily have been crawling with Italian heavy units waiting behind the horizon. He hadn’t. Because those units were either limping back to port or at the bottom of the sea.

Because she’d seen six repeated letters on a piece of paper and been crazy enough to chase them.

She slipped that slip of paper into the same envelope as Jeff’s last letter and slid them both under her pillow.

A week later, a new letter arrived from the Mediterranean, mailed long before the battle but delivered just in time for dramatic coincidence.

Hey kid, Jeff had written, in his sloppy, tilted hand. Got another convoy coming up. They keep telling us it’s all under control. I don’t know about that. But I do know I feel better knowing you’re in some smoky room somewhere doing math instead of out here. Feels like somebody’s got our backs.

He signed it, as always, Love, J.

He had no idea how literally that would turn out to be.

The Official Secrets Act—and its American equivalents—were very clear: no talking.

Maggie signed her life away in ink, promising never to breathe a word about Station Liberty or Enigma or Ultra or any of it to anyone who wasn’t cleared.

Not her parents.

Not Jeff.

Not the husband she’d meet, a fellow analyst with quick hands and a bad sense of humor, who’d share her bunk in cheap apartments and pass her coded notes between desks when workdays stretched fourteen hours long.

She and Doc Knox kept working Italian naval traffic all through 1941 and into ’42. The Italians, appropriately horrified by Cape Matapan, tightened up procedures. They trained their radio operators harder. They randomized padding better. They made fewer lazy mistakes.

But fewer wasn’t zero.

Once you understood how a machine could fail, you could spot the tiny ways it continued to falter. You could build new cribs from old ones. You could guess new keys from past patterns. Breaking Enigma once didn’t mean you had it forever, but it meant you’d stopped staring at a blank wall. Now you were dealing with a door. Sometimes it was locked. Sometimes somebody forgot to jiggle the handle.

The British called their intelligence “Ultra” because it was above top secret. It fed into every major decision in the Mediterranean. Convoys were rerouted around lurking submarines. Battleships didn’t sail on days the Italians had air cover ready. Eventually, when the Desert Fox ran out of fuel in North Africa, some of that was because tankers carrying his gas never made it past British submarines who knew exactly where to wait.

In the after-action reports and official histories, people would talk about “the advantages of Allied codebreaking” and “signals intelligence.” They’d mention Bletchley Park. They’d lionize Alan Turing and whichever admiral had the best publicist.

Maggie’s name would not appear.

She didn’t expect it to. Not really. She was a woman, nineteen, without a degree. When the war ended, she went back to school on the G.I. Bill that had been grudgingly extended to some civilians. She finished a degree in history. She married her fellow analyst, Keith. They moved to upstate New York. She started writing about something that had nothing to do with steel or guns: gardens.

She liked the way plants took chaos and made it look deliberate.

Jeff survived the war. He came home, carried some things in his eyes that never entirely left, but he made a life. He married. He had kids. When they got together at Thanksgiving, he’d slap her on the shoulder and say, “Good thing you didn’t join the Navy, kiddo. You’d have hated the food.”

Sometimes, after a glass of wine, he’d tell stories about convoy duty. About nights when they’d expected to see muzzle flashes on the horizon and instead just saw stars. About one particular run, near the end of March ’41, that had been so… uncannily smooth.

“Whole time,” he said once, “it felt like somebody upstairs nudged the game board in our favor. Like maybe, just for a week, the universe wasn’t totally out to get us.”

Maggie smiled and said, “Maybe you were due for some luck.”

She never said, “It wasn’t the universe, Jeff. It was a filler word.”

In 1974, long after the war had become something in movies and parades, the British and American governments finally loosened their grips on some codebreaking secrets. Enough years had passed that Enigma and its cousins were museum pieces. Enough technology had changed that no one was going to copy those old methods wholesale.

Books started to appear. The Codebreakers. Enigma. Ultra Secret. They talked about Bletchley Park, about the British mathematicians, about the huge bombes grinding through keyspace. A few mentioned “Italian naval work” in passing. None got the details right. Most didn’t mention Station Liberty at all.

One afternoon, Keith came home waving a newspaper.

“Hey, Maggie,” he called. “Looks like they’re finally letting the cat out of the bag. They’re talking about ‘us.’”

She took the paper, sat at the kitchen table, and read an article about codebreakers that included exactly one sentence on the Italian theater. It was so bland it could have been about crossword puzzles.

“How do you feel?” he asked.

She thought about the cottage. The cold. The smell of coffee and chalk and old smoke. The moment P E R Q U E had lit up on the Enigma’s lamps. The image of searchlights igniting the night above dark water. The little blue pins sliding safely into Egypt.

“Like someone summarized my entire twenties in a footnote,” she said.

Keith rested his hands on her shoulders. “Footnotes hold the whole story together,” he said. “Nobody reads them, but if you take them away, everything else starts to wobble.”

She snorted. “Very poetic for someone who once misspelled ‘cipher’ in an official memo.”

He kissed the top of her head. “I had a good editor.”

The recognition, when it came, was small and almost embarrassing. A plaque from the NSA. A certificate from GCHQ in Britain, acknowledging “significant contribution to wartime signals intelligence operations in the Mediterranean theater.” A quiet ceremony in a windowless auditorium in Maryland with stale cookies and bad coffee.

Someone mispronounced her last name as “Betty” over the microphone.

She shook the hand of a director she’d never meet again.

Later, when she was home, she tucked the certificate into a manila folder along with the old slips she’d stolen from Station Liberty when no one was looking: copies of the first decoded message, the internal memo about the Battle of Matapan, Jeff’s convoy report.

She didn’t hang it on the wall.

She didn’t need to.

She knew what she’d done.

In 2013, two months before Maggie’s ninety-second birthday, a college kid from Ohio emailed her out of the blue.

He was working on a podcast about “unsung World War II heroes,” he explained. He’d found her name in a declassified document about Italian naval Enigma. There wasn’t much there, but enough to intrigue him. Would she be willing, he asked, to talk about her work?

“To be honest,” he wrote, “I’m tired of hearing the same Turing and U-boat stories over and over. I want to tell people about the weird, tiny moments that actually turned the tide. Your name keeps showing up next to something called ‘Matapan.’ I had to Google it. That battle was insane. Five ships in one night? That’s… nuts.”

For a long time, she stared at the blinking cursor in the reply window.

Her fingers hovered over the keys.

She’d promised not to talk. But the promises had expiration dates. Most of the men who’d made her sign the forms were gone. The war had shrunk into history and then into nostalgia and then into background noise.

The kids needed stories. Not the big ones—the banner headlines and the speeches—but the small ones. The ones where a single human decision, a tiny human flaw, cascaded into something too big for any one person to take credit for.

She started to type.

She told him about Station Liberty’s creaking floors and cold radiators. About Doc Knox and his insistence that machines were only as good as the sloppy humans who fed them. About six letters that repeated when they shouldn’t have. About assuming something crazy—that an Italian petty officer had reused a filler word—and treating that assumption as a lever to pry open a machine the experts had declared invincible.

She sent the email before she could change her mind.

A few months later, her grandkids showed her a video online. A grainy headshot of her younger self, the only one she’d let the Navy take, faded and serious. A voiceover—American accent, fast, informal—telling the story in language aimed at viewers who’d grown up thinking encryption meant Wi-Fi passwords.

“Imagine this,” the host said. “You’re nineteen. You dropped out of college. You’re working in this freezing mystery farmhouse in Virginia. The smartest guys in the country have all said, ‘This thing can’t be cracked.’ And then you notice… six letters repeat. Same letters, same order. That is not supposed to happen. That’s where most of us would shrug and go, ‘Weird.’ But Maggie Batty? She bets the war on it.”

They’d dramatized some things, simplified others. They’d gotten the casualty count close—five ships, 2,303 Italians.

They’d called what she did a “crazy trick.”

She smiled at that.

It had been crazy. She’d known that at the time. She’d done it anyway.

When the video got to the part where the searchlights came on and the battleships fired, one of her grandsons—tall, awkward, face dotted with acne—whistled.

“That’s brutal,” he said. “Like… a slaughter.”

She nodded.

“It was,” she said quietly.

“And you…” He hesitated. “You kind of did that?”

The question hung there.

She thought of Jeff’s convoy. Of the ships that didn’t sink. Of the Italian sailors who never knew why the night had suddenly turned into day and then into fire.

“I helped make it possible,” she said. “That’s not quite the same thing as doing it. Admirals make choices. Captains give orders. Gunners pull triggers. Codebreakers move them around the board.”

“Do you ever feel bad about it?” he asked.

“Every war makes someone feel bad,” she said. “The trick is picking which someone you can live with. I decided I’d rather see my brother come home and some fascist admiral spend the rest of his career hugging the shoreline.”

He thought about that.

“That makes sense,” he said, slowly.

Later that night, lying in bed, she listened to the old farmhouse’s pipes rattle—different farmhouse, different state, same stubborn refusal to be quiet—and let her mind drift back to that cold room in 1941.

She could still see the page. The stupid, repeating SQPPBN. She could still hear Doc Knox’s voice: Prove it works.

If she hadn’t noticed?

If she’d looked up at the clock right then, or gotten distracted by a cough, or gone to get more coffee?

Maybe someone else would have seen it. Maybe not. Maybe the Italians would have sailed out of the dark and slammed into Jeff’s convoy. Maybe the Mediterranean would have tilted a little further toward Rome and Berlin. Maybe history would have diverged in a thousand subtle ways.

We like to tell ourselves big machines and big ideas run the world. But more often than not, it’s one person, in one room, noticing something that doesn’t look quite right—and being stubborn enough to chase it.

Machines have limits, Doc had told her once. Humans have hunches.

Maggie Batty—nineteen, half frozen, worried sick about her brother—had followed a hunch that everyone smarter than her would have called insane.

She’d looked at six repeated letters and seen the hinge of a naval campaign.

To the men on the Italian cruisers, the night of March 28 felt like an act of God. They never knew the “miracle” that killed them started in a farmhouse an ocean away, with a girl tapping a pencil against her thumb and muttering to herself.

They never knew that the weakness in their perfect machine wasn’t a wire or a rotor, but one of their own, bored and tired and typing the same filler word twice.

They never knew that a “crazy trick” and a set of quick, freezing fingers had turned their hunt into their funeral.

History almost didn’t know that either.

But the universe, however indifferent, occasionally allows the truth to leak out through cracks in the classification system.

Enough for a kid on the internet to say, wide-eyed into a camera, “So yeah, that’s how one girl’s crazy little pattern glitch sank five warships in a single night.”

Maggie smiled when she heard that line. For once, the headline wasn’t entirely wrong.

She closed her eyes.

In the dark behind her lids, six letters glowed: SQPPBN.

Then they resolved, one after another, into something softer.

P. E. R. Q. U. E.

Because.

She thought of all the “because”s that had stacked up over the years. Because she quit school. Because she said yes to a strange man with a clearance badge. Because a professor in a wrinkled suit believed in a nineteen-year-old’s instincts. Because a petty officer cut corners. Because a brother asked his kid sister to “do her bit.”

Because, because, because.

The causes didn’t excuse the effects. They didn’t diminish the dead or inflate the saved. They just… were.

Human fingerprints on the gears of history.

Maggie let out a slow breath and, for the first time in a long time, let herself feel unqualified pride.

Sometimes, one crazy trick is exactly what the moment needs.

THE END

News

My Coworker Tried To Sabotage My Promotion… HR Already Chose ME

When my coworker stood up in the executive meeting and slid that manila folder across the glass conference table, I…

My Sister Said, “No Money, No Party.” I Agreed. Then I Saw Her Facebook And…

My name is Casey Miller, and the night my family finally ran out of chances started with one simple…

Emily had been a teacher for five years, but she was unjustly fired. While looking for a new job, she met a millionaire. He told her, “I have an autistic son who barely speaks. If I pay you $500,000 a year, would you take care of him?” At first, everything went smoothly—until one day, he came home earlier than usual and saw something that brought him to tears…

The email came at 4:37 p.m. on a Tuesday. Emily Carter was still in her classroom, picking dried paint…

CH2 – They Mocked His “Farm-Boy Engine Fix” — Until His Jeep Outlasted Every Vehicle

On July 23, 1943, at 0600 hours near Gela, Sicily, Private First Class Jacob “Jake” Henderson leaned over the open…

CH2 – Tower Screamed “DO NOT ENGAGE!” – Illinois Farm Boy: “Watch This” – Attacks 64 Planes Alone

The first time anyone on the ground heard his voice that morning, it sounded bored. “Dingjan Tower, this is Lulu…

CH2 – A British Farmer Took Pity on German POW Girls — Decades Later, the Entire Village Were Amazed

If this were one of those long-form videos on an American history channel, the narrator would probably start like…

End of content

No more pages to load