December 8, 1944

Somewhere in the Ardennes Forest, Belgium

The radio was dying, and it was taking three battalions with it.

Captain Robert Chen hunched under a sagging shelter half strung between two fir trees, snowflakes dusting the shoulders of his overcoat and melting into the fabric. The cold clawed through his gloves as he pressed the headset tighter against his ears, as if his fingers alone could squeeze a signal out of the static.

Nothing. Just that dry, maddening crackle.

He glanced at the SCR-300 radio sitting in the snow beside his boots—a green metal backpack set with dials and a long whip antenna that disappeared into the white air. It was supposed to be the wonder box, the set that let infantry officers talk to artillery like they were in the next room. It had cost more than every rifle in his company put together.

Right now it wasn’t worth a plugged nickel.

“Anything?” he asked.

His radio operator, Corporal James Mitchell, had the other headset on, his nose red from the cold, fingers working the tuning dial with the slow, careful motions of a man whose hands no longer trusted themselves.

Mitchell shook his head.

“Just snow, sir,” he said. “Different flavor, same noise.”

Beyond their little patch of fir trees, the Ardennes forest stretched out in a maze of white trunks and black branches. Somewhere out there, in a sixteen-square-mile wedge of Belgium, more than 3,200 American soldiers waited on coordinates that Chen could not send.

Three battalions—infantry spread along a thin line, artillery dug into frozen fields behind them—were depending on his team to spot German positions and call in fire if the enemy moved. The Germans were massing. The scouts had seen signs—tracks in the snow, muffled engines, the occasional flicker of light where no light should be.

“Radio check, battalion, this is Able-Fox Two-Two, over,” Mitchell said into the microphone, his breath fogging around the mouthpiece.

The headphones answered with a burst of static that sounded like someone tearing paper very slowly.

Chen’s jaw clenched.

“Try backup frequency,” he said.

“We’ve tried all of ’em, sir,” Mitchell replied. “Twice. I even tried that Italian music station we were picking up last month. Nada.”

Chen looked past him, over the ridge, to where the sky was a little lighter. Somewhere beyond that lay battalion headquarters and three artillery battalions whose guns could throw shells ten miles.

Without the radio, those guns might as well have been on the moon.

“Tube problem?” Chen asked.

Mitchell shook his head.

“Swapped out the tubes an hour ago,” he said. “Checked the antenna, the power pack, the connectors. It’s not us.”

“Weather, then?”

Mitchell shrugged. “Radio worked fine in the rain at Anzio,” he muttered. “Guess it doesn’t like snow.”

Chen tried to ignore the hollow feeling crawling up from his stomach.

They’d been briefed on the SCR-300 back in England. Lightweight—if you considered forty pounds “light.” Rugged. Reliable. “Most advanced field radio in the world,” the Signal Corps officer had said, his voice full of conviction that sounded borrowed.

No one had mentioned that when the temperature dropped low enough, the damn thing might just give up.

Chen reached for the handset himself, more out of habit than hope.

“This is Able-Fox Two-Two, fire-control net, come in,” he said. “Any station this net, say again, any station this net, this is Able-Fox Two-Two—”

Static hissed back at him, as indifferent as the wind.

He handed the handset back to Mitchell, then opened his map case with stiff fingers. The paper was stiff and cold, the ink a little blurred from damp.

Three battalions, under his sector, hung on the thin line he traced with his gloved finger.

Without artillery support, if the Germans pushed, they’d be on their own.

He thought briefly—not with any real seriousness—about sending a runner. But in this terrain, in this cold, through these woods? No runner could move faster than German shells once the offensive began.

He stared at the useless radio for a moment.

“We’ll keep trying,” he said. “They’ll get it sorted at higher. Has to be a corps-level issue.”

Mitchell didn’t answer. They both knew that somewhere behind them, other officers were pressing other headphones to their ears and hearing the same dead snow.

Behind them, three thousand two hundred men waited for coordinates that weren’t coming.

Chen didn’t know it, not then.

He didn’t know that the salvation he needed wasn’t coming from some Signal Corps colonel in a warm bunker, or from a shipment of new radios by air.

It was coming from a girl in a factory in New Jersey who made sixty-two cents an hour and whose tools, at that moment, included a hairpin holding her hair off her face.

The Mystery at Fort Monmouth

Nine months earlier

March 1944, Fort Monmouth, New Jersey

The radios worked perfectly.

That was the problem.

Lieutenant Colonel Howard Brennan stood in the temperature test chamber at the Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories, hands on his hips, watching a technician in a white lab coat take readings off an oscilloscope. Outside, spring sunshine tried to warm New Jersey. Inside the chamber, the air was twenty degrees Fahrenheit and dropping.

On the metal rack in front of them, three SCR-300 radios hummed quietly, tubes glowing orange like sleepy fireflies.

“Forty degrees,” the technician said. “Signals are clean, sir. No deviation.”

Brennan’s jaw worked.

“Keep going,” he said.

They’d been at this for weeks. They’d run radios in heat, in cold, under vibration, in humidity that felt like a steam bath. They’d re-soldered connections, swapped tubes, checked every component.

Here, on benches in Fort Monmouth, the SCR-300 passed every test.

In Italy, up in the Apennines, the bastards were quitting.

“Thirty degrees,” the tech called out. His breath fogged in the cold air. “Radios still solid. No signal loss.”

Brennan could hear, in memory, the voice of the infantry captain he’d interviewed two weeks earlier, fresh from the front in Italy.

“…worked fine at dusk,” the captain had said, eyes tired, hands wrapped around a mug of coffee like it was the only warm thing left in the world. “Then it got cold. Couple hours before dawn, we tried to raise battalion. Nothing. Dead. Sat there in the dark, listening to that static, wondering if we’d missed a change in orders. I’ve never felt so damn alone.”

It wasn’t just a nuisance. During one operation, an entire company had spent eleven hours without contact because all three of their radios had gone bad the same night.

When dawn came and the radios warmed, they worked like nothing had happened.

“Twenty degrees,” the technician said. “Still good. No distortion.”

Standing just behind Brennan, Major Patricia Kowalsski hugged her clipboard closer to her chest. She was one of fourteen women technical officers in the Signal Corps, recruited not as novelty but as necessity. Men were overseas; the work here couldn’t wait.

She’d been the one to go to the Apennines, to sit with radio operators from frontline units and listen to their stories.

The pattern had been as obvious as it was maddening.

Fine during the day. Fine at dusk. Then, sometime after midnight, as the temperature dropped—silence. Not always. But often enough that the men had a name for it: “The Midnight Freeze.”

She’d typed up the field reports, highlighted the temperature ranges, circled the repetition.

Cold. Radios silent. Warm. Radios fine.

Brennan had read the reports, chewed on them, and thrown every test he could think of at the problem.

And still, here in the lab, the radios behaved like model students.

“Ten degrees,” the tech said. “Signals are starting to show minor noise on the scope, but still within tolerance.”

Kowalsski flipped through the latest batch of field reports.

“Intermittent failure rate: thirty percent of units in extreme cold,” she said quietly. “Same story from three different divisions.”

“Thirty percent,” Brennan repeated.

Out in the real world, where bullets flew and shells fell, “thirty percent” meant three out of ten platoons suddenly found themselves unable to ask for help at the worst moment.

Brennan looked at the radios, at the neat rows of wires and components.

Something was wrong, and it was hiding.

He just didn’t know yet that the person who was going to find it wasn’t in that building.

She was a few miles away, on a factory floor in Newark, with a pair of pliers and a notebook no one had asked her to keep.

Newark Nights

Continental Radio Manufacturing Plant

Newark, New Jersey

Second shift at Continental started when the sun went down.

The factory smelled like hot metal and rosin flux and tired people. Machinery clanked and whined on the first floor where presses stamped out metal chassis. Upstairs, under long rows of fluorescent lights, women bent over benches, soldering irons in their hands, weaving and inspecting the ropework of wires that would become the guts of military radios.

At Inspection Station 12, Margaret Flynn checked another harness.

She held it up to the light, turning it slightly, the way you might tilt a book to catch the sun.

Red, green, black: wires twisted in pairs and bundles, insulation shining under the lamps. She checked each solder joint against the spec sheet pinned to the brown wallboard, eyes flicking, hands steady.

No breaks. No cold joints. No mixed colors.

She made a small tick mark in her notebook and put the harness in the “pass” bin. Reached for the next.

Sixty-two cents an hour, she reminded herself, wasn’t bad.

It wasn’t good, either—not compared to the dollar twenty or more the male assemblers took home downstairs. But it beat weaving cloth in the textile mill, and it beat the nickel-and-dime jobs she’d had before that.

More importantly, it mattered.

On the wall across from her bench, a faded War Department poster showed a smiling GI with a rifle slung over his shoulder.

“His life is in your hands,” the slogan read.

She believed that.

Her brother’s best friend, Danny Keenan, had shipped out with one of the first units to North Africa. They’d grown up on the same block in Newark, trading baseball cards and milk money. His last letter had mentioned a “new radio set” that let him talk to tanks like they were next door.

If some bad harness crossed her bench and made it into one of those sets, someone like Danny might be out in the dark, pressing a headset to his ear and hearing nothing.

That thought did more to keep her focused than the posters.

Behind her, someone cleared his throat.

“Flynn,” Mr. Donnelly said. “Gather round. New spec sheets.”

Donnelly had run the wire inspection department for twelve years. He wore his tie too tight and his patience too loose. His gray hair curled above his ears like steam.

The inspectors pushed back from their benches and crowded around as he handed out thin sheaves of paper.

“The Army’s revised the harness for the SCR-300,” he said. “Redundant connections here, here, and here.” He tapped the schematic with a chewed pencil. “You all check solder points in red as Class A. That means shiny, no pits, no voids. Got it?”

The other women nodded, some scribbling notes. Most of them had been doing this long enough that changes in specs were just another piece of paper to file.

Margaret took the sheet and studied it.

The new lines ran along the right side of the diagram, parallel to the primary oscillator leads. Distance between them… she squinted… less than three-sixteenths of an inch.

She frowned.

The oscillator was the heart of the radio—at least, that’s what the manuals in the plant library had said. It set the frequency. It needed stability. She’d read about “interference” and “coupling” in the evenings, curled in the one armchair in the family apartment while her mother listened to the news on the Philco.

She’d also noticed something else.

In her little notebook, tucked under the blotter on her bench, she’d been jotting down numbers for months.

Dates. Contract numbers. And, lately, a column marked “Cold fails?”

Continental got some of the field returns back—units flagged by the Army as having failed in service. Sometimes the harnesses came back to her bench with red tags. “No fault found” was the usual conclusion. The harness would work just fine when they tested it warm.

Still, she’d noted that the paperwork on many of those red-tag units mentioned “cold weather operations,” “mountain,” “winter.”

There was a pattern there, stubborn as a stain no one else seemed to see.

Now they were adding wires alongside the oscillator leads.

Tighter than before.

More metal in close quarters.

She looked up from the diagram.

“Excuse me, Mr. Donnelly?” she said.

He was already halfway back to his office, tallying production totals on his clipboard. He stopped, turned, and frowned.

“Yeah, Flynn?”

“I have a question about the new wiring,” she said.

“It’s all there in black and white,” he said. “Extra eyes on those joints, that’s all. We’ve got quotas to meet.”

“I understand that,” she said carefully. “But I’m… concerned about the spacing between the redundant lines and the oscillator leads. In cold conditions, if the insulation contracts, the wires could get too close. At radio frequencies…”

His expression shifted as she spoke.

Impatience darkened into something like amusement.

“Flynn,” he said, “the spec comes from Army engineers. People with degrees. They’ve considered every factor. Your job is to inspect what they design, not redesign it.”

She felt heat rise in her cheeks.

“I’ve been tracking cold weather returns,” she said, a little more quickly. “We’ve had a higher number of SCR-300 harnesses coming back with field failure labels. The notes mention Italy. Mountains. Winter. If we run those redundant wires right next to the oscillator leads, I think it might make whatever problem is already there worse.”

Donnelly sighed.

“Engineers have been working on this for eight months,” he said. “You think they missed something a ninth-grade dropout in Newark caught in her spare time?”

The words stung, not because they were unexpected, but because they hit very close to the thin, sore place inside her where she kept her regrets about leaving school.

She swallowed.

“I think sometimes it helps to look at patterns from the bench, not just the drawing board,” she said.

For a heartbeat, he held her gaze.

She wasn’t challenging him, not exactly. She was just too stubborn to back down.

“Your concern is noted,” he said finally, in the tone of a man filing a piece of paper in a trash can. “This conversation is over. Get back to work.”

She did.

But she did not let it go.

Notebook and Hairpin

The plant library was a small room on the third floor, wedged between the drafting office and the stairwell. It smelled of paper and dust and something chemical—maybe the ink, maybe the glue.

Most of the women who worked at Continental never saw it.

Margaret had found it by accident one night when she’d taken the wrong set of stairs and followed the wrong hallway.

She had stood in the doorway, staring at the shelves of technical manuals, until the librarian—a thin man with glasses and a sympathetic beard—had cleared his throat.

“Can I help you?” he’d asked.

“Do you have anything on the SCR-300?” she’d replied.

That had been six months ago. Since then, her name had appeared on the checkout card of every manual that mentioned “oscillator,” “frequency,” or “field harness.”

Now, after her exchange with Donnelly, she spent her lunch break in there, the new spec sheet spread open on the table, SCR-300 assembly manual beside it.

She traced the oscillator circuit with her finger.

From the frequency crystal here… through the amplifier… along the leads…

The redundant wiring in the new spec took a path that paralleled the oscillator line for about six inches.

She imagined the harness in three dimensions, wires bundled, tied, twisted.

In warm conditions, the insulation—rubber, cloth—kept them separated. In the cold, that insulation shrank, stiffened.

At radio frequencies, two conductors running side by side behaved like the plates of a capacitor. Signal energy could “leak” from one to the other.

She didn’t know the math the engineers used to calculate capacitance. But she didn’t need the formulas to know that letting the oscillator’s “clean” frequency bleed into adjacent lines could smear the signal.

Which sounded a lot like “degradation.”

Which sounded a lot like “dead radios in Italy at midnight.”

She sat back, chewing on her lower lip.

The fix, in principle, was simple.

Keep the wires apart. Rigidly. No matter how cold it got.

But how?

Metal brackets would require a rework of the harness design. Plastic spacers would mean new tooling. None of that could happen overnight.

A scrap of wire? Maybe. Something springy. Something that could be bent into shape and clipped over the wires, holding them in place.

Something cheap.

She thought about it for three days.

While she tested harnesses. While she ate supper at the crowded kitchen table with her mother, her brother Thomas, and her kid sister Ellen. While she washed dishes, steam curling around her face.

On the third day, back at her bench, she reached up to tuck a loose strand of hair back under the pin that held it out of her eyes.

And stopped.

The hairpin was a simple piece of spring steel, bent into a narrow U-shape, flattened at one end. Every woman on the floor wore at least two. They’d been warned in orientation about loose hair around moving machinery.

She pulled it out and looked at it.

Flexible. Strong enough to grip hair. Strong enough to grip wires. Already mass-produced by the millions.

Cost? A pack of bobby pins was, what, fifteen cents at the corner store? That made each pin less than a nickel.

Maybe less if the Army bought in bulk.

That night, in the kitchen, after everyone else had gone to bed, she emptied her hairpins onto the table.

She dug Thomas’s needle-nose pliers out of his toolbox. She stole Ellen’s school ruler.

She bent.

Straightened.

Bent again.

She formed a series of clips, each one shaped to fit snugly over two parallel wires, keeping them separated by a precise quarter-inch gap.

She tested them on an old piece of lamp cord she’d stripped.

Clip. The wires sat in the grooves she’d bent into the pin, held firmly, not pinched.

She bent another. Tried a slightly different twist. Compared tension.

By midnight, her hands ached, but she had a little row of prototypes lined up like tiny steel seahorses.

She chose three that matched her measurements and slipped them into an envelope.

The next morning, she was at the plant an hour early.

“We’ll Test It”

“Five minutes,” she said, standing in the doorway of Donnelly’s office.

He looked up from his clipboard, eyebrows lifting as if she’d suggested knocking down a wall.

“It’s seven in the morning, Flynn,” he said. “What are you doing here? Your shift doesn’t start until eight.”

“I have a solution,” she said, holding up the envelope. “For the cold-weather radio failures.”

He set the clipboard down slowly.

“Unless you’ve got a spare general in that envelope, I don’t—”

“It’ll take five minutes to explain,” she said. “If I’m wrong, you can tell me to shut up and I will. But if I’m right…”

She let the sentence hang.

He sighed, pushed his chair back, and stood.

“All right,” he said. “Five minutes. If nothing else, I need the walk.”

At Inspection Station 12, she’d laid out a new SCR-300 harness on the bench—one built to the revised spec with the redundant wiring.

She unfolded the diagram and pointed.

“Here’s the oscillator,” she said. “Here’s the new line. They run parallel for six inches.”

He grunted.

“We’ve had a lot of field failures tagged ‘cold weather,’” she said. “I went back through the acceptance test records and cross-checked them with the harness batches. There’s a higher incidence in units built since we started using this revised layout.”

“You could just be seeing patterns where there aren’t any,” he said, but there was less bite in it than before.

“Maybe,” she said. “But if you run wires this close in parallel, you get capacitive coupling. Interference. If the insulation contracts in the cold, spacing decreases, coupling increases. Signal degrades. Which matches what the field reports describe—radios work fine until the temperature drops below twenty degrees. Then they get noisy or go dead.”

She opened the envelope and took out one of the bent hairpins.

“This keeps them apart,” she said.

She slid the hairpin over the bundle, the curved steel clipping around the two key wires she’d identified. The bent sections held them a quarter-inch apart.

“If we place three of these along the run,” she said, “the spacing stays constant. Even if the insulation shrinks, the wires can’t move closer than this.”

Donnelly picked up the harness, turned it over, and studied the little clip.

“This is… a hairpin,” he said flatly.

“Yes,” she said. “Spring steel. Already in mass production. Costs maybe four or five cents per unit in quantity.”

He kept looking at it.

“What I can’t do here,” she added, “is prove it. Not without cold testing.”

“We don’t have a fancy Army test chamber,” he said. “This is Newark, not Fort Monmouth.”

“We have the cold storage room,” she said. “Where you keep temperature-sensitive materials.”

He blinked.

“You want to put a harness in the freezer?”

“Two harnesses,” she said. “One standard, one modified. Leave them overnight. Tomorrow we take them to Testing, put them on the bench, run signal through them, and see which one sings and which one dies.”

He opened his mouth, closed it, then laughed once—short and surprised.

“You’re very sure of yourself, Flynn,” he said.

“I’m sure of the pattern,” she said. “And the physics, as far as I understand it.”

He weighed the harness in his hand.

“This is clever,” he admitted. “Very clever. But I can’t authorize a design change based on a theory from someone the Army doesn’t even know exists.”

“So let’s give them something they can’t ignore,” she said.

He stared at her for another moment, then nodded, more to himself than to her.

“All right,” he said. “Two harnesses. Two different outfits. Overnight in the cold room. If the tests show a difference… we’ll talk to Foster.”

Dr. Raymond Foster was Continental’s chief engineer. MIT twice over. He carried his degrees in his posture.

Margaret didn’t let herself think that far ahead yet.

That night, under Donnelly’s supervision, the cold-room attendant hung two harnesses on labeled hooks in the walk-in refrigerator at the back of the plant. Frost gathered on the metal racks. Breath steamed in the air. The thermometer on the wall read zero.

One hook: “Standard.”

The other: “Modified — Flynn.”

The next morning, the harnesses went to the testing department.

The test bench had an insulated platform, a signal generator, an oscilloscope tuned to show any noise on the line.

Technician Sam Hall, who’d been testing equipment since before Margaret had left school, clipped the standard harness into place first.

Signal on. Thirty above. Clean wave.

They extended the harness into a makeshift cold box—a metal box packed with dry ice, rigged in a hurry since they didn’t have a proper environmental chamber.

Temperature inside: twenty degrees. Then ten. Then zero.

Hall frowned.

“Getting spurs,” he said. “Lot of hash on the line. That’s ugly.”

“Quantify ‘ugly,’” Donnelly said, hovering behind him.

Hall twiddled the dial, watching the screen.

“Call it forty percent degradation,” he said. “Not what you want in the middle of a firefight.”

They ran the same test with the modified harness.

Signal. Warm. Clean.

Cold. Still clean.

Hall whistled.

“Well, I’ll be,” he said. “Whatever you’ve got on that rig, it’s doing the job. No extra noise. Rock steady.”

Donnelly looked from the scope to the hairpins, then over his shoulder at Margaret.

“How soon can you document this?” he asked.

She pulled a folder from her bag.

“I already did,” she said.

Inside were hand-drawn diagrams—top views, side views—of the hairpin clips, with dimensions down to the sixteenth of an inch. Assembly steps. Notes on placement.

She’d spent the last week drawing them by the dim light of the kitchen lamp, erasing and redrawing until the lines were clean.

For the first time since she’d met him, Donnelly smiled at her without condescension.

“You might just have something here, Flynn,” he said.

The Engineers

The conference room smelled faintly of coffee and pipe smoke.

Margaret sat at the far end of the long table, her notebook in front of her, hands folded to keep them from fidgeting.

On the other side, five men in suits and ties paged through the test results. At the head sat Dr. Raymond Foster, hair thinning, eyes cool, a pencil tapping silently against his teeth.

Donnelly had introduced her as “the inspector who came up with the hairpin modification.” That alone had made at least one of the engineers’ eyebrows climb.

“Miss Flynn,” Foster said now, without looking up, “walk us through your reasoning one more time.”

She did.

She talked about field failures tagged “cold weather,” about the timing with the revised harness spec, about the proximity of the redundant lines to the oscillator leads.

She explained, in words she’d pieced together from manuals and library books, how capacitive coupling between parallel conductors increased as spacing decreased, especially at radio frequencies.

She described the cold-room test, the oscilloscope traces.

Foster didn’t interrupt, but two of the others did, occasionally.

“What makes you think insulation contraction is significant enough to matter?” one asked.

“I don’t have precise coefficients,” she admitted. “But we know rubber stiffens and shrinks in the cold. Even a change of a fraction of a millimeter over several inches of run could affect coupling.”

The man nodded, grudgingly.

Another asked, “Why a hairpin? Why not design a proper spacer?”

“Because they need a solution now,” she said. “Thousands of radios are already in use. Manufacturing new harnesses would take weeks, maybe months. A hairpin is cheap, light, and already mass produced. You can ship a handful in an envelope and have a radio operator in Belgium install it in fifteen minutes with a pair of pliers.”

Foster finally looked up at that.

That was the other half of the problem. Not just finding the flaw, but fixing it in a way the Army could actually use in the field.

He set the pencil down.

“Miss Flynn,” he said, “how did you learn about capacitive coupling?”

She considered answering “the library,” but decided honesty would do better than modesty.

“I inspect harnesses eight hours a day,” she said. “I see how they’re built. I see which ones come back from the field with complaints. I read the manuals because I wanted to understand what I was looking at. When I saw the revised spec and thought about the cold-weather failures, the pattern seemed… obvious.”

One of the engineers snorted softly.

“Obvious to you,” Foster said, cutting the man off with a glance. “Not, apparently, to the lieutenant colonels at Fort Monmouth.”

He leaned back in his chair and steepled his fingers.

“The tests confirm your theory, Miss Flynn,” he said. “The modified harness eliminates the interference completely under cold conditions. The question now is how fast the Signal Corps can swallow their pride and change their procedure.”

Within twenty-four hours, Continental had packaged the test data, the diagrams, and a politely worded Engineering Change Request that boiled down, in plain language, to:

Your radios don’t work in the cold. Here’s why. Here’s a five-cent fix.

The request went out by courier to Fort Monmouth.

On the receiving end, in a stack of reports on Major Patricia Kowalsski’s desk, a folder with the Continental logo landed with a soft thump.

Kowalsski’s Call

Fort Monmouth, again

Major Kowalsski had developed a bit of a reputation around the labs.

Partly because she was a woman in an officer’s uniform carrying a technical briefcase.

Partly because she had a habit of returning from field trips with questions no one wanted to answer.

She sat now in her narrow office with the Continental folder open, reading the request.

Hairpin modification… wire spacing… capacitive interference… documented cold-weather tests…

She felt a prickle up her spine—the sensation of a puzzle piece finally finding its groove.

The field reports she’d brought back from Italy were still fresh memories. Men with chapped hands and hollow cheeks hunched over cups of bad coffee, telling her there had to be something wrong with the radios because they did everything by the manual and the damn things still quit when the temperature dropped.

She’d written her recommendations, urged further testing, then watched as the problem was bounced from desk to desk, each officer adding his initials and not much else.

Now some civilian outfit in Newark claimed to have the answer.

She flipped to the test data.

The oscilloscope traces from Continental’s cold-box tests were clear: the standard harness came apart under cold conditions, the modified one didn’t.

There, on the last page, someone had included a pencil sketch of the hairpin clip. In the margin, in a different hand, someone had written, almost amused: Bobby pin???

She smiled despite herself.

She marched the folder down the hallway to Lieutenant Colonel Brennan’s office.

He looked up as she knocked and entered without waiting for an answer, as was their quiet habit.

“Sir,” she said, dropping the folder on his desk. “You’re going to want to see this.”

He opened it, read, and his eyebrows climbed.

“A hairpin,” he said flatly.

“Yes, sir,” she said.

“How much do we pay Continental for these radios?” he muttered.

“Four hundred dollars apiece, last I saw,” she said.

He scanned the summary again, then looked up.

“You believe this is the answer?” he asked.

“It matches the pattern,” she said. “Timing with the revised harness spec. Cold-weather failure. Fix that requires no new manufacturing—just some bent wire and a pair of hands. It’s elegant.”

He grunted.

“Elegant” was not often a word applied to Signal Corps problem-solving.

He leaned back.

“All right,” he said. “We’re not taking a civilian contractor’s word on faith. We’ll replicate their tests. Today.”

Within hours, five SCR-300 sets in the Fort Monmouth lab wore improvised wire clips shaped out of hairpins supplied by a slightly bewildered secretary.

They went into the temperature chamber.

Down the thermometer slid.

Eight hours later, Brennan and Kowalsski stood looking at oscilloscopes that showed clean, stable signals.

“It works,” the test tech said. “In the cold, in heat, under vibration. It just works.”

Brennan exhaled, a long breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding for months.

“All right,” he said. “Patricia, you get the fun job. We need this in Europe yesterday. Harness replacement is out. We can’t pull thousands of radios out of line. How fast can we push a field modification out?”

She thought for a moment.

“Hairpins are cheap and light,” she said. “We can ship bags of them by air. One tech sergeant in each division, a jeep, and Margaret Flynn’s instruction sheet. They go unit to unit, retrofit in place.”

“Margaret who?” he asked.

She tapped the cover of the folder.

“Continental attributes the modification to one of their inspectors,” she said. “Nineteen-year-old. No degree. Works nights.”

Brennan stared at her, then shook his head and laughed once.

“Eight months of engineers beating their heads against a wall,” he said. “And a girl in Newark holding her hair up finds the missing brick.”

“It’s not a bad metaphor, sir,” she said.

He straightened.

“Get it done,” he said. “Write up the field mod instructions in plain language. Diagrams, big arrows, no math. I want couriers on planes by morning.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

As she left his office, she allowed herself one brief, private smile.

Somewhere out there, in some factory, a young woman who got paid half of what a man did for the same work had just out-engineered a roomful of colonels.

And somewhere even farther out, in a snowy forest in Belgium, a captain and a corporal stared at a dead radio and wondered how they were going to keep their men alive.

Hairpins to the Front

The Ardennes, December 10, 1944

Two days of static.

That was how long Captain Chen’s world had been narrowed to the hiss in his headphones and the growing certainty that the problem was not going away on its own.

The cold had settled in deeper. Frost rimed the edges of foxholes. Men huddled in twos and threes, their breath hanging in clouds. Rumors moved through the ranks like smoke—German armor massing, something big coming.

Chen felt naked without the radio net.

He’d been a schoolteacher in California before the war. He’d stood in front of chalkboards and explained algebra to sixteen-year-olds who’d rather have been anywhere else. Clarity had been his job—making numbers make sense.

In the Army, they’d handed him binoculars and a radio and told him his new job was to see what the enemy was doing and make it make sense to the artillery.

He took that job very seriously.

Which was hard to do when the instrument that connected his eyes to the guns refused to cooperate.

On the third day of radio silence, a jeep ground its way up the icy track to his observation post.

Chen stepped out from under the fir branches, hand on the butt of his pistol more out of habit than fear. The jeep’s windshield was down, its canvas top dusted with snow.

A tech sergeant in Signal Corps brassard and heavy gloves climbed out, flexing his fingers.

“Captain Robert Chen?” he called.

“That’s me,” Chen said. “You’re a long way from a warm tent, Sergeant.”

The sergeant’s breath puffed white as he grinned.

“Tech Sergeant Daniel Woo, Signal Corps,” he said, offering a gloved hand. “I’ve got something for you, sir. Straight from the wizards at Fort Monmouth.”

Behind him, in the jeep’s back seat, a wooden box sat wedged between coiled cables and a toolbox.

Chen raised an eyebrow.

“If it’s a new radio, I’ll take two,” he said.

“Not exactly,” Woo said.

He walked around to the back, flipped the lid off the box, and reached in.

His hand came out holding… a small cardboard packet. The kind Chen’s kid sister might have carried in her purse.

Woo tore the top off the packet and shook a single object into his palm.

A hairpin.

Black, thin, slightly curved.

Chen stared at it.

“You came all the way up here to give me a woman’s hairpin?” he asked.

Woo’s grin widened.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Apparently this five-cent trick is going to save your three-battalion radio net.”

Mitchell, who had wandered over at the sound of the jeep, peered at the pin.

“You’re kidding,” he said. “That thing’s going to fix a four-hundred-dollar radio?”

Woo shrugged.

“Orders from the top, Corporal,” he said. “Some civilian inspector back in Jersey figured out a flaw in the harness wiring. They tested it every which way at Fort Monmouth. It works. We’re retrofitting as many sets as we can reach.”

He handed Chen a folded sheet of paper.

“Field Modification Instructions — SCR-300 Cold Weather Harness,” the heading read.

Underneath, in clean, legible lettering, were step-by-step instructions and three simple diagrams.

The style looked… feminine, Chen realized. Not that letters had genders, but something about the way the curves flowed reminded him of his mother’s grocery lists.

“Who wrote this?” he asked aloud.

“Name on the engineering change paperwork was ‘Flynn,’” Woo said. “Margaret. She works at Continental. That’s all I know. I’m just the delivery boy.”

Chen read the sheet quickly.

Remove the back cover. Ease out the harness. Locate the oscillator leads—red and green, labeled. Identify the redundant lines. Bend hairpin into specified shape. Clip over wires at three marked positions, maintaining quarter-inch spacing.

Reassemble. Test.

He exhaled.

“All right,” he said. “Mitchell, get the toolkit. Sergeant Woo, you can walk me through this while we freeze our fingers off.”

They set the radio on an ammo crate in the lee of a tree to shield it from the wind.

Mitchell unscrewed the back panel and swung it open, exposing the dense forest of wires and components inside.

Woo leaned in, breath fogging over the chassis.

“Okay,” he said. “Here’s your oscillator bundle. See the red and green twisted pair? And here’s your redundant circuit running parallel. That’s the problem child. We’re going to keep ’em from getting too friendly with each other.”

He took out a small pair of needle-nose pliers from his kit and bent the hairpin into a squared-off U, following the little drawing on the instruction sheet.

Mitchell watched, then mimicked the shape on a second pin.

“This is going in my memoirs,” he muttered. “The day we fixed a radio with bobby pins.”

“Make that three battalions,” Chen said absently, eyes scanning the treeline while they worked.

They slid the first clip over the wires, guiding the oscillator leads into one groove, the redundant line into the other. The spring tension of the steel held them in place.

Two more clips along the run.

All told, the modification took twelve minutes.

Mitchell reassembled the radio, fingers moving more quickly now that there was something like hope in the air.

“Power up,” Woo said.

Mitchell flipped the switch. The tubes glowed faintly.

He put on the headset, pressed the earcups down, turned the tuning knob.

For a second, there was the familiar hiss of static.

Then, like a voice emerging from a crowded room, a clear tone cut through.

“…Fox Two-Two, this is Battalion, do you read, over…”

Mitchell’s mouth fell open.

“Jesus,” he breathed. Then louder: “Yes, sir, we read you! This is Able-Fox Two-Two, radio check green, over!”

He shoved the spare headset at Chen.

“Take it, sir.”

Chen pressed it to his ears and heard the clean, blessed sound of someone on the other end of the line.

“Fox Two-Two, this is Battalion,” the voice said. “We’ve been trying to raise you for two days. Authentication Charlie-Three. Report situation, over.”

Chen felt something unclench in his chest.

“This is Able-Fox Two-Two,” he said. “Authentication Charlie-Three confirmed. We’ve observed enemy movement in grid squares—” He rattled off the coordinates he and his observers had been sitting on, useless, for two nights. “Request immediate fire mission from all batteries able, over.”

“Fox Two-Two, roger,” Battalion replied. “Stand by for fire missions, over.”

Within twenty minutes, the first shells were on their way.

Chen stood in the snow, headset on, watching as distant flashes from friendly guns lit the horizon and dark columns of smoke began to bloom where German units had been staging.

Next to him, Woo tucked the remaining packets of hairpins back into his box.

“I’ve got ninety-nine more of these to deliver before dark,” he said. “Hope they’re all this appreciative.”

Chen looked at the small, ordinary thing in his hand—the U-shaped sliver of steel that had made the difference between shouting into the void and calling down steel on the enemy.

“Sergeant,” he said, “next time you get back to wherever this came from, I want you to pass along a message.”

“I can try, sir,” Woo said. “There’s a lot of layers between here and Newark.”

“Doesn’t matter,” Chen said. “Just tell them… tell her… whoever thought of this, that she gave us our voice back.”

Woo nodded.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

He climbed into his jeep, gears grinding as he set off toward the next unit.

Mitchell watched him go, then looked at the radio, cables snaking into the snow like roots.

“Imagine that,” he said. “All these tubes and coils and Army dollars… and the thing that saves the day is something my kid sister uses to keep her bangs out of her eyes.”

Chen smiled grimly.

“If it works, Corporal,” he said, “I don’t care if it’s held together with chewing gum and rosary beads.”

Behind them, artillery shells whistled overhead, their arrival downrange marked by dull concussions that rolled through the frozen forest.

Three battalions had their fire support back.

Because somewhere, nine months earlier, a girl at a factory bench had refused to ignore a pattern.

Recognition

January 15, 1945

Fort Monmouth, New Jersey

The ceremony was small.

A few rows of folding chairs. An American flag on a stand. A lectern that had seen more lectures than awards.

Margaret stood at the side of the room, feeling strange in her best dress instead of her factory slacks, hair braided and pinned in a way that made her feel both younger and older.

She had never been on an Army base before. Men in uniforms moved through the corridors, some with stripes, some with bars, some with stars. The sound of typewriters and telephones hummed behind office doors. Outside, trucks rattled past on the road.

Mr. Donnelly sat in the third row, his tie straighter than she’d ever seen it. Dr. Foster occupied the second row, beside a woman in uniform with major’s oak leaves on her shoulders—Major Kowalsski, introduced to her earlier as “the one who pushed your modification through.”

At the front, Brigadier General William Harrison cleared his throat.

“Miss Flynn,” he said, beckoning her forward.

Her legs felt a little rubbery as she walked to the lectern.

Harrison held a small case in one hand, a piece of paper in the other.

“When we started getting reports of SCR-300 failures in cold weather,” he said, “this post spent eight months trying to figure out why. We tested components, we analyzed circuits. We froze perfectly good radios trying to make them fail here the way they failed in Italy.”

A few chuckles rippled through the room.

“We didn’t solve it,” Harrison went on. “Not here. Not with all our degrees and labs. The solution came from someone we’d never met. Someone who, frankly, we didn’t know existed until very recently.”

He looked at her, smiling.

“Miss Margaret Flynn, wire harness inspector at Continental Radio Manufacturing,” he said. “Who noticed a pattern, trusted what she saw, and had the courage to tell people who outranked her—by quite a bit—that something in our design was wrong.”

He opened the case and took out a medal on a ribbon.

“On behalf of the Signal Corps and the United States Army, I’m authorized to award you the Meritorious Civilian Service Award,” he said. “For identifying and solving a critical design flaw that had significant impact on combat operations.”

He pinned the medal to the front of her dress.

It felt heavier than it looked.

He shook her hand.

“What impressed me most,” he said more quietly, just for her, “wasn’t just that you found the solution. It was that you persisted after people told you to get back in your lane.”

She thought briefly of Mr. Donnelly’s first reaction. Of the word “dropout.”

“I just paid attention to patterns,” she said. “And I didn’t like the idea of radios dying in the cold when someone was depending on them.”

He smiled.

“Keep not liking that,” he said.

Afterward, in the hallway, Dr. Foster caught up with her.

“You’ve made us all look very clever, Miss Flynn,” he said dryly. “Continental’s getting a lot of praise for its ‘innovative engineering.’”

“You did the tests,” she said.

“You did the thinking,” he replied. “We’d be fools not to use more of that.”

He cleared his throat.

“We’d like to offer you a promotion,” he said. “Technical inspector. More responsibility. More authority to flag potential design issues. Pay to match.”

Her heart thumped.

“That’s very generous,” she said, trying not to sound as breathless as she felt.

“It also comes with a condition,” he added. “We’ll sponsor you for engineering courses at Newark College of Engineering, if you’re interested. Part-time, evenings. You’d keep working with us.”

She stared at him.

“Me?” she said, before she could stop herself.

“Yes, Miss Flynn,” he said, amused. “You. You’ve already demonstrated an engineer’s instincts. Might as well get you the credentials to go with them.”

She thought of the notebook under her bench. Of the manuals in the plant library. Of the way the oscillator circuits had started to look less like arcane diagrams and more like stories she could read.

“I’m interested,” she said.

“Good,” he said. “Consider this the first of many designs you’ll improve.”

Major Kowalsski joined them then, smiling.

“Congratulations,” she said. “You’ve made a lot of radio operators very happy.”

“I’m glad,” Margaret said. “Do you think—” She hesitated. “Do you think I’ll ever hear from… any of them?”

“The soldiers?” Kowalsski asked.

“Yes,” she said. “I know that sounds… silly. But I keep thinking how they must feel out there when the radios work again because of a hairpin.”

“It doesn’t sound silly at all,” Kowalsski said. “And I’d be very surprised if you don’t get at least one letter.”

She was right.

In April 1945, an envelope with an APO address arrived at the Flynn apartment in Newark.

Margaret sat on the edge of the bed she shared with Ellen and read the neat handwriting, hands trembling slightly.

Dear Miss Flynn,

I wanted you to know that the radio modification you designed reached my unit in December during some of the most difficult days we experienced.

The ability to restore communication made a difference I cannot adequately express in words. Because of your ingenuity, I could coordinate support for the men under my command. Because of your persistence in pursuing a solution despite resistance, we had the tools we needed when we needed them most.

I don’t know if anyone has properly thanked you for this. So please accept my gratitude on behalf of everyone who benefited from your work.

You gave us our voices back when we needed them most.

Sincerely,

Captain Robert Chen

112th Infantry Regiment

She read it twice. Three times.

Then she slid it into her notebook, between her early scribbles about oscillator leads and wire spacing.

If anyone asked her, years later, what her proudest achievement was, she would show them that letter.

Not the medal. Not the degree. Not the patents.

That letter.

The Long Echo

The war ended.

The SCR-300s, with their hairpin-steadied harnesses, kept talking through the last offensives into Germany, through final skirmishes on cold hills and cautious patrols along quiet rivers.

In Norway and Italy, in Belgium and the Vosges, signal units followed Fort Monmouth’s instructions, bending hairpins into clips, sliding them over bundles, laughing in disbelief when the static cleared.

By late December 1944, more than three thousand radios in the European theater had been modified with Margaret’s trick. Failure rates in the cold dropped from around thirty percent to under two.

Commanders stopped cursing the sets and started trusting them again.

Back home, the engineering journals took notice.

In March 1946, the Journal of the Institute of Radio Engineers ran a dry, technical article about “Field Modification to Mitigate Temperature-Dependent Capacitive Interference in SCR-300 Harnesses.”

Buried in the middle, it credited “M. Flynn” with the initial insight about wire spacing and insulation contraction.

The article noted, in its understated way, that the modification cost the Army approximately four cents per radio in materials, took fifteen minutes to install, and had saved at least $160,000 in parts and shipping costs compared to replacing harnesses wholesale.

It did not attempt to quantify how many lives had been saved by radios that worked when the mercury fell.

Margaret started evening classes at Newark College of Engineering that fall.

She walked into lecture halls full of men in tweed jackets and Army surplus coats and took notes in precise handwriting.

She worked days at Continental as a technical inspector, red-flagging design quirks, suggesting alterations, earning a reputation as a young woman you ignored at your peril.

She learned the math behind the instincts she’d already been using.

She graduated in 1951, one of a handful of women in a sea of dark suits, and took her place in Continental’s engineering department.

Over the next quarter century, she worked on transistorized radios, early satellite communication systems, the first fumbling attempts to link computers over long distances.

She filed patents. She gave talks. She mentored younger engineers—men and women both—who sat in conference rooms and heard her tell the story of the hairpin.

“Engineering isn’t about showing off how smart you are,” she would tell them. “It’s about solving problems that matter, with whatever you’ve got. Sometimes that’s a million-dollar lab. Sometimes it’s a five-cent piece of wire holding your hair back.”

Signal Corps officers toured the Continental plant years later and told new hires the story from their side—the freezing radios, the frustration, the unexpected fix.

Somewhere in Georgia, at the Signal Corps Museum at Fort Gordon, an SCR-300 sits behind glass, a faded olive-drab backpack case with a whip antenna.

Next to it, under softer lights, a small display holds three items: a coiled wire harness, a bent hairpin clip just big enough to fit over two wires, and a folded instruction sheet.

The caption reads:

“Field modification developed by civilian inspector Margaret Flynn (Continental Radio) to correct cold-weather failures in SCR-300 radio sets. Implemented across European Theater, winter 1944–45. Material cost per unit: approx. $0.04. Operational impact: significant.”

Visitors drift past.

Some smile at the idea that something so small could matter so much.

Others, the ones who’ve had to fix things with whatever was at hand, nod as if of course it was like that.

In Chicago, years after the war, Captain (now Mister) Robert Chen keeps a different memento in his desk—an old, slightly rusted hairpin he’d pulled from the bottom of a supply crate after the war.

He shows it to his kids once, when they ask about the medal in his closet and the map on his wall.

“This,” he says, “is what saved our hides in the Ardennes. Not just this exact pin, but an idea like it. A girl in Jersey thought our radios shouldn’t die in the cold. She figured out how to keep them alive.”

He doesn’t remember her name until he digs out the copy of the letter he sent in 1945.

When he reads “Dear Miss Flynn” again, his throat tightens.

He wonders briefly what she did with her life.

In Newark, decades later, a retired engineer named Margaret sits in her kitchen with a cup of tea, a stack of old papers on the table.

On top lies a yellowed copy of Captain Chen’s letter.

Below it, her first notebook from Continental—pages filled with neat diagrams and the early seeds of a theory that became a field mod.

Her arthritis makes her fingers stiff, but she can still pick up a hairpin and bend it with a certain familiarity.

She laughs softly at herself.

All the satellites, all the conferences… and this is the story they keep asking for.

“How did you fix the radios with a hairpin?”

She never minds telling it.

Because it is, in its bones, an American story.

Not in the mythic sense of lone geniuses and overnight miracles, but in the quieter ways.

A teenage girl who didn’t finish high school, working second shift, paying attention.

A factory that bothered to listen to one of its lowest-paid employees when she had something to say.

An Army that, however grudgingly, adopted a “not invented here” fix because it worked.

A captain in a frozen forest, willing to trust a piece of bent wire he’d never seen before.

A small act of stubborn attention rippling outward through wires and snow and time.

In December 1944, in the Ardennes, the SCR-300 radio had a flaw that turned the most advanced field communication system in the world into a dead box when the temperature dropped.

The fix did not come wrapped in an official stamp.

It came from a five-cent hairpin.

From a girl who refused to believe that “good enough” was good enough when men’s lives were on the line.

And three battalions, spread across sixteen square miles of Belgian forest, heard artillery on the way again instead of static.

Because Margaret Flynn looked at a diagram, frowned, and thought, That’s too close.

Because she had the nerve to say so.

Because someone, finally, listened.

THE END

News

I showed up to Christmas dinner on a cast, still limping from when my daughter-in-law had shoved me days earlier. My son just laughed and said, “She taught you a lesson—you had it coming.” Then the doorbell rang. I smiled, opened it, and said, “Come in, officer.”

My name is Sophia Reynolds, I’m sixty-eight, and last Christmas I walked into my own house with my foot in…

My family insisted I was “overreacting” to what they called a harmless joke. But as I lay completely still in the hospital bed, wrapped head-to-toe in gauze like a mummy, they hovered beside me with smug little grins. None of them realized the doctor had just guided them straight into a flawless trap…

If you’d asked me at sixteen what I thought “rock bottom” looked like, I would’ve said something melodramatic—like failing…

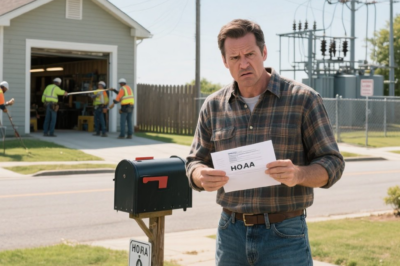

HOA Cut My Power Lines to ‘Enforce Rules’ — But I Own the Substation They Depend On

I remember the letter like it was yesterday. It came folded in thirds, tucked into a glossy HOA envelope that…

I Overheard My Family Planning To Embarrass Me At Christmas. That Night, My Mom Called, Upset: “Where Are You?” I Answered Calmly, “Did You Enjoy My Little Gift?”

I Overheard My Family Plan to Humiliate Me at Christmas—So I Sent Them a ‘Gift’ They’ll Never Forget I never…

“We gave your whole wedding fund to your sister. She deserves a proper wedding.”

I always assumed that if my life imploded, there would at least be warning signs—sirens, flashing lights, maybe an earthquake….

My Mom’s New Boyfriend Grabbed My Phone—Then Froze When He Heard Who Was Speaking…

By the time the sirens started screaming down our street, the turkey had gone cold. The holiday music had died…

End of content

No more pages to load