At 20,000 feet above the Tunisian desert, the tail of All-American started to walk away.

Tail gunner Sam Sarpalus felt it before he saw it. One moment the big Boeing B-17F was plowing steady through the thin blue air, engines droning that familiar four-part harmony. The next, the whole rear end of the airplane lurched upward like it had run into a wall.

The sound hit him a split second later—metal tearing through metal, a shriek so loud it cut through the engine noise and drilled into his bones. His turret shuddered, plexiglass buzzing around his head. For an instant he thought a shell had detonated inside the aircraft.

Then daylight exploded where daylight wasn’t supposed to be.

Sam twisted in his cramped compartment, looking forward through the narrow tunnel that connected his tail position to the rest of the fuselage. His blood went cold.

A diagonal gash ran across the belly and side of the airplane, a jagged open wound that started on one side of the fuselage and ended near the other. Sunlight poured in, throwing hard white stripes across twisted aluminum and torn insulation. Beyond the rip he could see the Sahara twenty thousand feet straight down.

The tail section he was sitting in no longer lined up with the rest of the bomber. It was canted off to the right, swaying a good foot and a half out of alignment. It moved with a slow, sickening lag, like a door on busted hinges.

Sam didn’t know it yet, but he was effectively riding in a separate airplane—one connected to All-American by a few bent spars, a narrow strip of skin on the right side of the fuselage, and whatever mercy the laws of physics had left.

He keyed his intercom, throat dry.

“Tail to cockpit,” he said. “We been hit bad. I repeat, we been—”

His voice vanished under the roar of wind hammering through the wound.

Twenty minutes earlier, it had been just another trip home from hell.

February 1, 1943, three hundred miles northwest of Biskra, Algeria. The 97th Bombardment Group was turning back from Tunis, its mission done. Bomb bays were empty, gun barrels hot, and the flight formation had relaxed into that tired, loose trailing stack that meant “we’re not dead yet.”

They had hit the German-controlled port hard—warehouses, dockside fuel, anything that would make life miserable for Rommel’s supply officers. Flak over the target had been nasty but not crippling, a black, blooming garden they’d punched through at altitude. A couple of holes in the skin, one rattled gunner, nothing that kept them from forming back up over the coast.

Kendrick Robertson “Sunny” Bragg Jr., twenty-five years old, Georgia born, football man from Duke before the war, sat in the left seat of All-American’s cockpit. His hands rested easy on the yoke, fingers stained with grease and sweat. Beside him in the right seat, co-pilot Guy Boyd scanned the sky and engine gauges, a cigarette unlit at the corner of his mouth, waiting for the “smoke break” at the end of the mission.

“Not a bad Sunday drive,” Boyd said, peering past his oxygen mask at the wingtip of the lead aircraft. “I’ve seen worse.”

“You jinx me, I’m throwing you out without a chute,” Bragg drawled back.

He said it lightly, but in the back of his mind something darker ticked off numbers. They all knew the odds. In Europe, the average life expectancy for a bomber crew was eleven missions. All-American was already working her way through that ledger. Twenty-five missions was supposed to be a full tour. The math never did add up neatly.

Behind them, navigator Harry Nuill hunched over his chart table, pencil moving in cramped little arcs as he plotted their way home across an expanse of sand that, from twenty thousand feet, looked like an ocean somebody had drained.

Bombardier Ralph Burbridge, crouched in the nose, had his hands resting on the black metal body of the Norden bombsight. The thing sat there like a captured piece of alien technology—an $8,000 analog computer wrapped in glass and secrecy. During the bomb run, it had flown the aircraft like it always did, whisper-fine corrections through electric servos while Ralph watched the crosshairs drift over the target.

Now, bomb bay doors closed and target behind them, the Norden sat idle. Its little gyros spun, humming to themselves.

In the radio compartment, flight engineer Joe James listened to the background murmur of the interphone, eyes flicking between his panel of engine instruments. Waist gunners Elton Cond and Mike Zuk stood at their open windows, .50s slung on pintles, scanning for fighters. Ball turret gunner Elton Cond—smallest man on the crew, jammed into a clear glass bubble underneath the fuselage—watched the world spin slowly below his boots. Radio operator Paul Galloway checked frequencies and thought about the coffee back at Biskra.

Back in the tail, Sam Sarpalus sat with his knees pulled up, eyes on the sky behind them. He’d been the last line of defense more than once. Today the sky was clear, blue, bumping along gently with the usual little thermals.

That’s when the call came from the top turret.

“Bandits! Two o’clock high, coming in!”

The air inside the bomber snapped taut.

Two gray shapes slashed out of the sun, rolling in from above and ahead of the formation, angular and murderous.

Messerschmitt fighters. B-109s. They looked like sharks compared to the fat American bombers, all slender noses and big props and lethal intent.

Every man in All-American knew what to do without being told. Shoulders tightened. Fingers found charging handles.

“Gunners, open fire at will,” Bragg said into the intercom, voice flat.

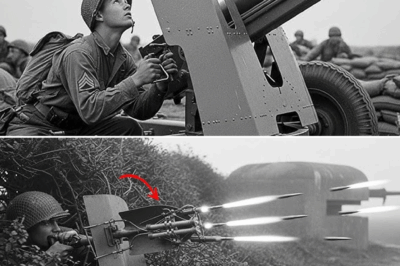

Lead bomber’s top turret opened up first, twin fifties stuttering lines of orange fire. Other ships joined in. The sky filled with tracers, bright threads of red and white reaching for the darting gray shapes.

One Messerschmitt swooped too close to the overlapping arcs. Somebody caught him square. He belched smoke, rolled over on his back, and dropped—wing over wing, a black smear dragging behind him, vanishing into the yellow haze below.

The second fighter kept coming.

Its pilot was Feldwebel Eric Poxia, sixteen-victory ace, the kind of man whose picture might have been on a German recruiting poster somewhere. He’d survived Russia. He’d survived the Mediterranean. He wasn’t planning on dying over the Sahara.

He lined up on All-American’s belly, 20mm cannons blinking, and made his run.

Gunners aboard Lid Bomber and All-American both stitched him. Heavy slugs stamped holes across his wings, chewed into his engine block, shattered something vital in the nose.

But battle damage didn’t obey polite physics. A hit didn’t always flip a plane over neatly and send it tumbling away.

Sometimes a wounded bird did exactly the wrong thing.

Poxia’s Messerschmitt bucked, rolled, and instead of breaking off clean, it drifted down and in, directly across All-American’s path. Maybe he was dead at the controls. Maybe he was half-conscious, hands too slow. Either way, his fighter dropped under the bomber’s belly like a knife slipping under a rib cage.

Bragg saw a flash of gray in the corner of his eye, felt a chill that had nothing to do with altitude.

“Hang on—”

He didn’t finish the sentence.

The Messerschmitt’s wing sliced into the B-17’s fuselage just aft of the waist gun positions, carving a brutal diagonal through the semi-monocoque shell. It chopped clean through the left horizontal stabilizer and most of the fuselage frame, like an axe driven three-quarters through a tree trunk.

The impact sounded like the world ending.

The tail kicked up. The nose dropped. All-American yawed, rolled, tried all at once to tear itself apart.

In the cockpit, the yoke was suddenly a meaningless wheel in Bragg’s hands. He pulled. Nothing. He pushed. Nothing. The familiar, living resistance of the control surfaces was gone.

“Flight controls!” he barked. “I’ve got nothing!”

“Same here!” Boyd shouted, knuckles white on his yoke.

Behind them, steel control cables that ran the length of the fuselage—linking their hands to the tail’s rudder and elevators—hung in ragged, flapping ends, sliced like strings on a broken guitar.

In the tail, Sam Sarpalus saw the sky where the airplane used to be and realized he was alive not because of design, but because of blind luck.

The manual was brutally clear about this sort of thing.

Every training lecture, every emergency procedure, every fireside war story from old hands boiled down to one truth: catastrophic structural failure in a heavy bomber meant one thing.

You bailed out.

If your tail broke half off, you abandoned ship. If you lost your elevators and rudder, you abandoned ship. You didn’t argue with physics. You didn’t argue with Boeing’s engineers. You didn’t argue with gravity.

But nobody had written the procedure for what to do when you were twenty thousand feet over a desert that wanted to kill you just as badly as the enemy did.

Bragg’s mind ran the math in flashes.

They were three hundred miles from Biskra. Below them, the Sahara spread out in endless shades of tan and gold. It wasn’t empty—nothing in wartime North Africa was truly empty—but it was contested. Rommel’s Afrika Korps might have been in retreat, but German and Italian patrols still prowled. The front line wandered like a drunk across the map, shifting day by day.

If his crew bailed out now, ten parachutes would drift down into a no-man’s-land of rocks, scrub, and shifting loyalties.

Some might land near Allied troops. Some might land near Axis patrols. Some might come down hard on a ridge, break an ankle, crack a spine. Nights were cold enough to kill a man who couldn’t move. Days were hot enough to bake him dry.

Maybe six out of ten would survive long enough to see another bomber. Maybe fewer.

On the other hand, he was trying to fly an airplane whose tail was attached by habit and a few metal threads, with no rudder and no elevators.

Every expert he’d ever met—flight instructors, engineering officers, grizzled captains in ready rooms—would have told him the same thing: you cannot fly a B-17 without tail control. Not for long.

The aircraft would wander into a climb or a dive, oscillate, build up forces, and eventually tear itself apart. You might get one heroic moment of level flight. You were not getting ninety minutes.

“Cockpit, this is radio,” Galloway’s voice came over the interphone, ragged. “We… we still flying?”

“More or less,” Boyd muttered.

Bragg stared straight ahead through the windshield. The horizon wobbled, but it was still there. The engines hummed. The wings hadn’t fallen off.

Not yet.

He reached down and keyed the intercom master.

“Crew,” he said. His voice came out even, full, the way it did when he called signals on the football field. “Stand by to bail out. Don parachutes and wait on my order.”

In the nose, Burbridge froze, one hand on the bombsight.

In the waist, Cond and Zuk looked at each other.

In the ball turret, Elton swallowed hard.

Back in the tail, Sam craned forward, staring at the swinging tunnel and trying not to think about how far it was to the ground.

Bragg let his finger rest on the switch another second, then took it off.

He could hear his flight instructors in his head, could practically feel some Boeing engineer waving a slide rule at him, insisting that this was suicide.

He thought about his crew instead. Ten men who’d flown with him over flak and fighters for months. Men who trusted him with their lives, in a way no referee had ever trusted him with a football.

They had signed up to fight Germans, not to die quietly in a desert while arguing with a sand dune about which side it was on.

“All right,” he said quietly.

He looked over his shoulder.

“Joe,” he called. “Get back there and tell me how bad it is.”

Flight engineer Joe James unbuckled from his jumpseat behind the cockpit and started aft.

The fuselage, normally a single solid tunnel of aluminum and rivets, was now a creature that flexed under him. The floor trembled. The skin creaked.

He squeezed past the radio compartment, through the waist gunner section where Cond and Zuk held onto their guns and tried to look useful. The wind from the gash tore at his clothes, yanked at the maps tacked to the bulkhead, fluttered loose insulation like shredded cotton candy.

When he reached the edge of the wound, he stopped dead.

Three-quarters of the way across the fuselage, there was simply… nothing. No floor. No skin. No frame. Where there should have been aluminum and stringers and ribs, there was open blue air and, far below, an awful lot of sand.

The left horizontal stabilizer—one of the broad tailplanes that made the B-17 such a steady platform—was gone, cleanly severed. Only the right side remained, and even that was held on by what looked like a drunk welder’s last few tacks.

The tail section—Sam’s old home—hung out behind the wound, connected to the rest of the plane by a handful of twisted frame members on the right and a scrap of torn skin on the top. It swayed with each gust, a lazy, horrible pendulum.

Joe’s brain, which had spent years learning about load paths and stress concentrations from maintenance manuals, tried to convince him this was an illusion. The rest of him knew better.

He keyed his throat mic.

“Cockpit, this is James,” he shouted over the howl of the slipstream. “We’re cut three-quarters through, maybe more. Left horizontal’s gone completely. Tail’s hanging on the right side only. If it lets go, it’s taking the tail gunner with it.”

Silent beats passed on the line.

“Can we keep flying?” Bragg asked.

Joe glanced back at the swinging tail, then at the nothing under his feet.

“Sir, by the book, no,” he said. “By reality… it’s somehow still here. But if that tail tears free, it may hit the stabilizer that’s left. Might rip the rest off. Recommend we get Sarpalus forward now. Tunnel’s warping. He waits, he’s not getting through.”

“Copy,” Bragg said. “Get him moving.”

Joe crawled closer to the tunnel, grabbing handholds where he could.

“Sam!” he yelled. “You still back there?”

The tail gunner’s voice came back tight. “Yeah!”

“You gotta come forward now. Tail might not ride with us the whole way.”

There was a pause. Sam had spent the last few minutes in a box of plexiglass watching the rest of his airplane threaten to leave him behind. The idea of climbing out into that swaying, narrowing passage didn’t thrill him.

“Copy,” he said anyway, because staying put wasn’t much of a plan either.

He swung his legs out of the turret, grabbed the sides of the tunnel, and started hauling himself forward. The fuselage flexed under his hands, the opening yawning wider beneath his knees. He tried not to look down.

“Don’t think about it,” Joe said, reaching back for him. “Just keep coming. One grab at a time.”

Sam gritted his teeth, feeling every sway, every metallic groan. A gust of wind shoved the tail sideways another few inches; the tunnel’s edges creaked, narrowing.

He made it through with inches to spare, Joe grabbing his harness and yanking him into the waist section as the passage buckled a little more behind him.

They both lay there for a second, panting.

“You’re done with that seat for today,” Joe said.

“No argument here,” Sam replied, voice shaky.

Up front, All-American was still miraculously flying, but “flying” had become a generous word.

With the elevator and rudder cables severed, Bragg and Boyd had no normal way to control pitch or yaw. The yokes moved freely in their hands, connected to nothing but their own fear. Ailerons on the wings still responded—roll control was there if they needed it—but with that tail damage, heavy banking was a good way to finish the Messerschmitt’s job.

The bomber wanted to do its own thing. It rolled and hunted, tail wagging behind them like a broken kite.

On a normal day, the solution would have been obvious: get to a safe bail-out altitude, put her on autopilot, and walk out, one after another, into the sky.

Bragg’s gaze slid sideways, resting for a moment on the metal case mounted between them on the cockpit ceiling. The automatic pilot unit. It took inputs from the same cables that no longer existed. Useless now.

He set his jaw.

“Nobody bail out yet,” he said into the intercom. “We’re staying aboard. We’re going to see if we can fly this girl home.”

There was a ripple of disbelief down the line.

“Sir, with no tail—” someone began.

“I’m aware of what we don’t have,” Bragg cut in. “Until we’re over friendly ground, bailing out’s a last resort, not a plan.”

he let that sit. People needed orders. They also needed to know he wasn’t just whistling in the dark.

And then, somewhere in the back of his head, a memory floated up. A training session in Florida. A bombardier’s lecture he hadn’t quite slept through.

The Norden.

“Harry!” he called. “Ralph!”

In the nose, Ralph Burbridge startled.

“Yes, sir?”

“That bomb sight of yours,” Bragg said. “You told me it talks to the autopilot, right? Flies the plane on the bomb run.”

“Yes, sir,” Ralph said slowly. “We sync it to the C-1 autopilot. Norden feeds it corrections. It actuates servos in the tail to trim us on heading and altitude.”

He paused, seeing where this was going and not liking it.

“Sir, the cables—”

“The cables to our wheels are cut,” Bragg said. “But you said those servos are back by the rudder and elevators themselves. Electric motors, right? Wired straight in?”

“Yes, sir. Cables to the autopilot unit, electric lines to the servos.”

Bragg’s heart kicked.

“Then the cables between our yokes and the tail can be lying in the desert for all I care,” he said. “You might still have a line.”

Ralph stared at the Norden like he’d never seen it.

He had been told this thing was for one sacred purpose: putting bombs on target. He’d memorized the oath about destroying it rather than letting it fall into enemy hands. He knew the combination of the safe they stored it in between missions. He knew how to baby its gyros, how to lead an entire formation over a target using its math.

He had never heard anyone say, “Use it to fly us home.”

“Sir, we only ever use it for a few minutes on the run,” Ralph said. “I’ve never—there’s no procedure…”

“Can it control pitch?” Bragg demanded. “Rudder?”

“Yes, sir. In theory.”

“Then we’re using it,” Bragg said. He looked over his shoulder. “Harry, you feed him headings. Ralph, you’re flying this bird. You and that little miracle box.”

In the nose, Ralph’s hands hovered over the controls. The bombardier’s station was a cramped cave of glass and metal, the bombsight mounted on a pedestal directly in front of him, pointing out into the slipstream.

“Me?” he blurted.

“You,” Bragg said. “You’re the only one with a control system that’s still talking to our tail.”

There was a beat of silence in the interphone, the kind that happened when everybody in a ten-man crew processed the same crazy thought.

In the next bomber over, some Boeing engineer would have fainted.

Ralph swallowed.

“Roger that,” he said. “I’ll do it.”

He reached for the Norden’s controls, hands trembling only slightly.

Behind him, Bragg turned back to Boyd.

“We’re not completely dead yet,” he said. “We still got throttles.”

Boyd nodded, already there. “Four engines, four levers,” he said. “Differential thrust.”

“Exactly,” Bragg said. “We push up on the left pair, she’ll want to yaw left. Throttle back on the right, she’ll follow. Might be enough to keep our nose where we want it.”

“It’s crude,” Boyd said.

“Crude’s fine,” Bragg replied. “Crude beats falling.”

Out over the desert, All-American began to fly in a way no B-17 had ever been asked to fly before.

Bragg and Boyd took the throttles in both hands, nursing power settings like surgeons working a dying heart. Push on the left engines, feel the nose swing gently left. Ease on the right to bring it back. Combos of all four to keep airspeed right in the narrow window between “not enough lift” and “too much stress on that maimed tail.”

Back in the nose, Ralph synced the Norden to what was left of the autopilot, flipping switches he’d only touched for practice, routing control through the little analog brain into electric lines that ran aft to the servo motors near the crippled tail surfaces.

He nudged the bomb sight’s control handles.

Tiny impulses flowed down the wires, into the servos. The motors whirred, their gears turning minutely, moving the elevator and rudder just enough to trim the bomber.

Normally, those electric corrections were layered on top of the pilot’s own inputs, smoothing things out, holding a precise course on a bomb run.

Now they were it. The only tail input All-American had left.

The tail, already swinging eighteen inches out of line with each breath of wind, responded late and exaggerated, like a drunk trying to follow dance steps.

Ralph gritted his teeth and tried to think ahead of it.

He wasn’t a pilot. He was a bombardier. His job description said “calculate trajectories,” not “save ten men by turning a secret bomb sight into the world’s strangest flight control system.”

He did it anyway.

“Okay,” he muttered, mostly to himself. “If the tail’s swinging right, I need to start feeding left before she gets there…”

He eased the control bar. The nose dipped a hair. The tail’s sway damped, a fraction of an inch less violent.

“Ralph?” Bragg’s voice ghosted down from the intercom. “How’s she feel?”

“Like steering a car with the wheel connected to the tires by rubber bands,” Ralph shot back. “But she’s responding.”

That was enough.

Bragg looked at his airspeed indicator. Nearly 180 miles an hour, normal cruise. The tail shuddered every time they hit a bump. Fast air was good for lift. It was hell on the damage.

He eased the throttles back until the needle settled around 155.

At that speed, the wings still carried them. The tail—such as it was—still held on. Any slower and they risked a stall, a wing dropping, a roll they might not have room to catch. Any faster and turbulence threatened to finish what Poxia had started.

A tightrope, strung between Tunis and Biskra.

“Ninety minutes,” Nuill said from his chart table, doing the math. “At this speed, we’ve got about an hour and a half.”

“Then let’s not waste ‘em,” Bragg said.

He keyed the intercom again.

“Crew, listen up,” he said. “We’re still in the air. Burbridge has us trimmed. Boyd and I’ve got some kind of steering. We’re turning for home. Keep your chutes on. Eyes peeled for fighters. We’ll reassess when we’re over our lines.”

He could have told them they were one servo failure away from spinning into the desert. One unexpected gust away from the tail finally walking off.

Instead he said, “We’re doing fine. We’re going to make it.”

Sometimes leadership was honesty. Sometimes it was selective honesty.

Behind them, the rest of the formation tightened around All-American as long as they dared.

Bragg’s B-17 flew wounded and slow. The others throttled back to stay with her, guns still scanning for more gray shapes in the sky. For a while, they formed around her like a moving shield, unwilling to leave her alone out there.

But fuel didn’t care about feelings. Eventually, they had to make their own call. Formation leaders gritted their teeth, gave farewell radio calls, and pushed their throttles forward.

The other bombers pulled ahead, little silver crosses on the horizon. One of them, camera already mounted in the navigator’s window, captured a photograph as they passed.

In it, All-American flies with a yaw to her tail, a great silver wound slashing across her flank, daylight visible straight through her body. It looks like she should already be in pieces.

She wasn’t. Not yet.

Now she was alone.

Back at Biskra, they saw the photograph before they saw the plane.

Major Robert Coulter, who had led the day’s mission, stood in the operations tent of the desert airfield, dust swirling in through the flaps, sweat drying on his neck. He held the photo between thumb and forefinger, angling it toward the light.

There was no way to sugarcoat what it showed.

The 97th’s engineering officer, Captain William Morrison, peered over his shoulder.

“Jesus,” Morrison said softly.

The picture didn’t lie. Three-quarters of the fuselage aft of the waist was hanging open. The left horizontal stabilizer gone. The tail aligned only by stubbornness and a few strips of metal.

“You said he leveled out after the hit?” Morrison asked.

Coulter nodded. “I watched him.”

“He’s still transmitting,” the radio operator at the corner table added. “We’ve been getting position reports.”

Morrison shook his head slowly.

“Bob, that’s not survivable,” he said bluntly. “If what you saw is what this photo shows, that tail should already be gone. And even if it isn’t, he’s got no rudder, no elevators. You can’t control a B-17 like that. He might keep it straight for a while, but the second he tries to land, the stresses—”

“He says he’s coming home,” Coulter said. “Says he’s going to try.”

“That’s suicide,” Morrison snapped. “We should order him to bail out now, while he’s over sand we control.”

Operations officer Captain James Harrison stepped in.

“If they bail out, they’re scattered across the desert,” he said. “Half of them break something. Night falls, temperature drops. Maybe they get picked up. Maybe they don’t. Maybe the first friendly they see has a swastika on his armband.”

“And if he tries to land an airplane that’s already halfway in the scrap pile?” Morrison shot back. “He flares, tail takes the load, snaps off, they cartwheel. All ten dead.”

The tent filled with overlapping arguments.

“He might not even have landing gear!”

“Hydraulics go aft, too—”

“Better a busted leg on the ground than a funeral detail picking up what’s left off the runway—”

“Harrison’s right—”

“No, engineering says—”

The flap opened.

Lieutenant Colonel Frank Armstrong stepped in, ducking his head against the sunlight. Dust shone in the air around him as everybody shut up.

Armstrong had been with the 97th since the beginning. He’d watched them fly out over French ports and Italian marshalling yards, counted them back in through smoke and haze, and written too many letters to too many families when the numbers didn’t match.

He held out his hand. Coulter gave him the photograph.

Armstrong studied it a long moment, face unreadable. Then he passed it to Morrison again.

“Bill,” he said. “From an engineering standpoint, can that airplane land safely?”

Morrison didn’t hesitate. “No, sir,” he said. “Not under any textbook I’ve ever read.”

Armstrong turned to Harrison.

“From a survival standpoint,” he said, “what are his crew’s chances if they bail out now?”

Harrison exhaled.

“Better than zero,” he said. “Maybe sixty-forty they all make it back, eventually. Maybe.”

Armstrong walked to the operations map, traced the line from Tunis back to Biskra with a fingertip.

He’d been a bomber pilot himself before the war. He knew what it felt like to sit in a cockpit and have someone on the radio tell you your odds from the comfort of solid ground.

“Here’s what we’re going to do,” he said. “We’re going to clear the runway. Every ambulance, every fire truck, every medic we’ve got, lined up and ready. Then we’re going to talk to Lieutenant Bragg.”

“Sir—” Morrison began.

Armstrong raised a hand.

“We are not ordering that crew to jump or to land,” he said. “We’re going to inform their aircraft commander of his options and let him make the call. He knows the condition of his ship. He knows his crew. We don’t second-guess that from a tent.”

He nodded at the radio operator.

“Get me All-American.”

Up in the thin air over the desert, Bragg had settled into a grim rhythm.

His left hand rode the inboard throttles, right hand the outboards. Boyd mirrored him, ready to nudge or grab as needed. They fed power back and forth in little pulses, keeping the nose pointed generally west. The compass drifted, corrected, drifted again.

Behind them, Nuill called out headings and drift corrections, eyes flicking between the chart and the drifting world beyond his ports.

In the nose, Ralph sat hunched over the Norden, a tethered man steering a wounded giant.

He didn’t think about how long he’d been at it. He thought about the feel of the airplane under his hands. Each nudge on the bomb sight hit those servos a fraction of a second later and translated into a lazy rise or fall in the nose, a slow twist in the tail.

The tail’s swing had become something like a heartbeat to him. He could feel when it started to wander too far and feed a little correction just before it did. If he waited until it moved, he was too late. He had to trust his gut.

Sweat ran down his back in cold trickles despite the altitude.

At some point, Galloway came on the intercom and said, “Ralph, you doing okay up there?”

“Ask me in ninety minutes,” Ralph muttered.

Static popped in their headsets.

“All-American, this is Biskra,” a voice said. “Come in.”

Bragg thumbed his mic.

“Biskra, All-American,” he said. “We read you. Go ahead.”

“This is Lieutenant Colonel Armstrong,” the voice replied. Calm. Steady. “We’ve seen the photograph of your aircraft. We have some idea what you’re dealing with.”

Bragg looked at the hole behind him without turning. He could imagine the picture.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “We’ve seen it up close.”

There was a pause.

“Lieutenant,” Armstrong said, “from what we can tell, your aircraft has suffered catastrophic structural damage aft of the waist. Engineering believes a landing attempt is extremely hazardous. However, if you bail out, your crew will be scattered across desert that is not fully under our control.”

“Understood, sir,” Bragg said.

“We are clearing the runway,” Armstrong went on. “All emergency services will be standing by. You are authorized to attempt a landing at your discretion. If you believe that’s not possible, you are authorized and encouraged to bail out when you deem conditions safest. The decision is yours, Lieutenant.”

Bragg let that sink in.

The decision had been his since the moment Poxia’s wing cut them open. But hearing it said out loud was a different kind of weight.

Somewhere in the back, somebody whispered, “What’re we gonna do, Sunny?”

He didn’t answer that voice right away.

He thought about the football field at Duke, four years before the war. Fourth and long, last quarter, coaches yelling from the sidelines, crowd roaring. The safe play versus the one that might actually work if you had the guts to call it.

He thought about Joe’s voice over the intercom, talking about the tail, about Sam nearly trapped back there. He thought about Ralph in the nose, hands glued to the Norden, inventing a new flight procedure with every breath.

He thought about the Sahara below and the desert nights that could freeze you where you lay.

“Biskra,” he said finally. “We copy. We appreciate the options.”

He glanced at Boyd, at the needles on the panel, back at the horizon.

“We’re coming home,” he said. “Advise emergency crews to stand by.”

“Roger, All-American,” Armstrong said. “Runway is yours.”

Bragg cut the intercom to the ground, flipped back to the internal channel.

“Crew, this is the pilot,” he said. “You heard the colonel. We can jump into the sandbox and hope the right folks find us first. Or we can try to put this girl down and walk away as a group.”

He paused just long enough.

“I’m taking her in,” he said. “If any of you can’t live with that, speak up now and we’ll talk you through bailing out when we’re over friendlier terrain.”

Silence. Then, one by one:

“Radio copies. I’m staying.”

“Waist gunner. I’ll take my chances on wheels.”

“Ball turret. I ain’t about to climb out of this sardine can into the sky if I don’t have to.”

“Tail gunner here. Already crawled through hell once today, skipper. We finish it together.”

Nobody chose the silk.

“Okay then,” Bragg said quietly. “Let’s bring her home.”

Ninety minutes after a Messerschmitt fighter had ripped her almost in two, All-American limped toward Biskra airfield.

The desert runway appeared first as a thin gray line on the horizon, then as a strip scratched into the sand, ringed with tents and trucks and men who all suddenly had very little else to do but stare.

At the edge of the strip, ambulances and fire trucks lined up nose-to-tail. Medics stood ready with stretchers and bandages. Ground crews clustered in clumps, shielding their eyes against the glare as they looked north.

On the operations tower, Armstrong raised binoculars.

“There,” someone said.

A speck appeared in the blue. It grew, resolving into a familiar shape marred by an unfamiliar wound.

Through the glass, Armstrong saw it: the tail offset, the huge diagonal gash in the fuselage, the way daylight shone straight through the back third of the bomber when the angle was just right.

“Good Lord,” he murmured.

As All-American crossed the field at two thousand feet, three red flares arced from her cockpit—signals of distress, of wounded aboard, of “clear my way.”

She banked away gently, starting a wide, lazy circle to set up for landing. It was not the crisp, steep pattern of a healthy bomber. It was a slow, careful dance, Bragg and Boyd working the throttles, Ralph feeding the Norden tiny corrections, all three men aware that any violent turn might make the tail finally give up.

On her downwind leg, the runway stretched out beneath and behind them. Turning base, the airfield slid off Bragg’s left shoulder. Final approached like the end of a sentence.

“Okay,” Bragg said, more to himself than to anybody else. “Let’s not mess this up.”

“Air speed one-four-zero,” Nuill called. “Altitude fifteen hundred.”

Bragg breathed in through his nose, out through his mouth. They had no flaps—hydraulic lines severed with the tail. No flaps meant a higher approach speed and a shallower angle, more runway needed to stop.

They also had no tail wheel, or at least no guarantee that it still worked. If it did, it would be a miracle. If it didn’t… they’d find out soon enough.

“Ralph, I need us rock steady,” Bragg said. “Shallow glide, no sudden anything.”

“I’ve got you,” Ralph replied, hands white on the Norden’s bars.

He could see the runway through the plexiglass of the nose, a strip of gray rushing up at them. He watched for drift, fed a touch of rudder here, a hint of elevator there, trying to keep their descent smooth.

“Altitude thousand,” Nuill said. “Speed one-thirty-five.”

On the ground, Morrison watched through his own binoculars.

“He flares, that tail’s going to take the whole load,” he muttered. “It’ll snap right—”

“Enough, Bill,” Armstrong said quietly, eyes never leaving the approaching bomber.

“Five hundred feet,” Nuill called. “Speed one-thirty.”

Bragg eased the throttles back, feeling the airplane settle, its weight shifting onto their shared judgment. The nose dropped slightly.

“Little nose-up, Ralph,” he said.

Ralph nudged the Norden. Somewhere aft, the servos whined, the mutilated elevator shifted. The nose rose a degree.

The runway filled the windshield. Bragg could see the vehicles lined up alongside. Could see medics staring up at him. Could see one of the fire crews making the sign of the cross.

“Two hundred feet,” Nuill said, voice higher than normal. “Speed one-twenty-five.”

“Hold it,” Bragg murmured. “Hold it…”

“One hundred. One-twenty.”

The aircraft seemed to hover in that last hundred feet, every bump magnified, every gust a hand trying to shove them off course. Bragg flew with his fingertips on the throttles, mooding power in little pulses.

“Fifty. One-fifteen.”

“Ralph, give me a kiss of nose-up,” Bragg said. “Just a kiss.”

The bombardier obliged. The nose tipped up another hair. The main gear, fixed and sturdy under the wings, angled toward the concrete.

“Thirty.”

“Twenty.”

The first contact with Earth was almost gentle.

The main wheels kissed the runway, bounced once, then settled. The B-17’s suspension absorbed the shock, giving them something they hadn’t felt in ninety minutes: a sensation of solid ground pushing back.

“Touchdown,” Boyd breathed.

Bragg pulled the throttles to idle, feet finding the brake pedals.

“Easy,” he said. “Nice and easy…”

They rolled. Ninety. Eighty. Seventy miles an hour.

Back where the tail used to be, where structure gave way to air, the hanging section finally dropped.

With no functioning tail wheel and a jagged edge instead of a smooth skid, the torn metal slammed into the runway.

The sound reached the crew as a long, grating shriek, like a hundred nails dragging across a blackboard the size of a barn.

The airplane lurched. For a sick second, Bragg felt the tail trying to swing them sideways. Ground loop, Morrison’s voice whispered in some corner of his head. When a crippled aircraft digs a tail in and spins, flipping and rolling, shedding wings and lives.

“Hold her!” Boyd yelled.

Bragg did. He pressed the left brake a hair more than the right, kept his hands light on the throttles even though they were at idle. The plane wanted to swing. He didn’t let it.

Looking out his left window, he watched sparks geyser up from behind them as the torn tail dragged down the runway, showering the concrete with burning metal.

Sixty. Fifty. Forty.

Then, finally, blessedly, they were just a rolling box of battered aluminum coming to a stop.

Thirty. Twenty. Ten.

All-American shuddered to a full halt. Silence crashed into the cockpit.

For three full seconds, nobody moved.

Then Bragg exhaled and keyed the intercom.

“Crew, report,” he said.

One by one:

“Radio okay.”

“Waist okay.”

“Nobody in the tail to ask.”

“Ball okay, bit shaken.”

“Bombardier… I think I just flew an airplane, sir.”

Laughter crackled down the line, half hysterical, half relieved.

“Everybody’s accounted for,” Bragg said. “Nobody’s dead. I’ll take it.”

He reached up, flipped the battery switch to off. The cockpit fans wound down with a soft whine.

Outside, ambulances and fire trucks converged, sirens whooping. Men with stretchers sprinted toward the bomber’s side door.

The ground crew clustered around the gash, staring. Up close, the damage was worse than the photograph.

The fuselage skin folded back like a peeled sardine can. Internal frames were torn and bent at impossible angles. You could stand on the ground and look straight through the bomber’s body out the other side.

Engineering officer Morrison walked up slowly, eyes wide. He reached out and laid a hand on a torn frame, as if to reassure himself it was real.

“This is impossible,” he whispered. “This airplane should not have flown.”

The side hatch popped open. A figure dropped to the ground: flight engineer Joe James, eyes blinking in the sunlight. He stared around at the sea of faces.

Behind him, the rest of the crew started to emerge, stiff and blinking and grinning like drunks.

Ralph climbed down from the nose, hands still curled like he was holding the Norden’s controls.

Sam dropped to the ground and looked back at the tail that had tried to leave him behind.

Finally, Bragg stepped out of the cockpit, sliding down to the ground.

A medic rushed up, stretcher ready.

“Are you hurt?” he demanded. “Any injuries? Who needs—”

Bragg waved him off with a tired grin.

“No business, Doc,” he said, Georgia drawl as thick as red clay. “We’re walking in.”

Behind him, All-American stood, an icon of aluminum stubbornness.

The photograph of All-American in flight—the one Cliff Cutforth had snapped from the neighboring bomber—made the rounds fast.

It showed a B-17 with a tail that had no business attached to anything but a junkyard, cruising level over the desert like she didn’t know she was supposed to be dead. It became a symbol of the Flying Fortress’s toughness, plastered on morale posters and newspaper front pages.

Stories sprouted around it like weeds.

Back home, people said the crew had tied the tail on with parachute cord. They said they’d been flying back to England, not to a dusty strip in Algeria. They said they’d jettisoned their bombs after the hit, not before. The legend took on a life of its own, the way good stories always do.

Years later, in one of his last interviews before his death, bombardier Ralph Burbridge chuckled when he heard the tall tales.

“No, we didn’t tie the tail on with rope,” he said. “Nothing back there to tie it to, anyway. And we weren’t flying back to England. It was three hundred miles from Tunis to Algeria. We’d already dropped our bombs on the way in. The Messerschmitt hit us going home.”

What he did confirm, and what mattered more than the rumors, was the heart of it.

“Nobody had ever used the Norden like that before,” he said. “We were making it up as we went. Every input I made, I didn’t know if it would help or make things worse. But Lieutenant Bragg trusted me. And I wasn’t going to let him down.”

The engineers took notes. Somewhere in a manual, a new line appeared: “In the event of primary tail control cable failure, the Norden bombsight autopilot system may provide limited emergency pitch and yaw control sufficient to maintain level flight until crew can bail out.”

They wrote it like a footnote. They didn’t mention that a crew of ten had already flown that line right up to its edge and then beyond, all the way to a full-stop landing.

All-American herself got a second life.

The damage was too severe for her to go back to front-line bombing, but the mechanics at Biskra shook their heads, rolled up their sleeves, and did what Americans always did with bent machines: they fixed what they could and repurposed the rest.

She flew again as a “hack”—a utility ship hauling cargo, personnel, and mail between bases. No one ever shot at her quite so viciously again. In March 1945 at Lucera Airfield in Italy, with the war’s end in sight and shelves of new airframes waiting, she was finally dismantled for salvage.

After surviving the impossible, All-American was broken down for parts to help other birds fly.

All ten men who’d been aboard her that day over Tunisia survived the war.

Tail gunner Sam Sarpalus never again took a solid tail for granted. Joe James kept crawling out into dangerous spaces to tell pilots what they really didn’t want to hear. Harry Nuill kept drawing lines on maps and measuring the distance between fear and home.

Ralph Burbridge went home with a story nobody quite believed when he told it right, so he learned to tell it short instead.

Lieutenant Kendrick “Sunny” Bragg went back to Georgia, got into real estate, and mostly kept his mouth shut about being the guy in that one famous picture.

When people asked, he shrugged.

“We did what we had to do,” he’d say. “Desert didn’t look friendly. The old girl still had some fight in her. We just hung on.”

He died in 1999 at the age of eighty-one, a quiet man from Savannah who had once looked at a shredded tail and a set of dead controls and refused to accept that “impossible” meant “already decided.”

The 414th Bombardment Squadron, which had watched All-American limp back, adopted a new emblem: a happy little puppy praying on top of a damaged tail section. Someone started humming a song with a line about “coming in on a wing and a prayer,” borrowed from another damaged bomber’s story. The phrase stuck anyway.

The real legacy of All-American and her mad, patched-together flight control rig wasn’t in the patch art or the posters. It was in the way airplanes changed afterward.

Engineers took note. Redundant systems became more than an idea—they became doctrine. Multiple hydraulic lines. Electric backup controls. Separate paths for critical cables. “Fly-by-wire” decades later would take the concept of separate control routes and turn it into an art.

Modern pilots sit in glass cockpits with computers that cross-check each other a thousand times a second. Somewhere in that chain of thinking, there’s a line that runs back to a bomb sight in a B-17 nose over Tunisia, and a bombardier who used it to fly home.

But even more than that, the lesson lived in the heads of anyone who ever heard the story and understood what it really said.

Sometimes the manual isn’t enough.

Sometimes the problem you’re staring at wasn’t anticipated by the men who wrote the rules. Sometimes the engineers, the instructors, and the experts are all correct on paper—and still wrong about what a handful of stubborn people can pull off when the alternative is unacceptable.

On February 1, 1943, ten men sat in a bomber over the Sahara with half a tail, no cables to their rudder or elevators, and a creeping certainty that they had no right to be alive.

One of them looked at a top-secret bombsight and thought, Well, it moves the tail, doesn’t it?

One of them thought, Four throttles still work.

All of them thought, in one way or another, We’re not done yet.

They used what they had. They trusted each other. They ignored the odds. They turned “impossible” into “hard, but doable.”

And a wounded Flying Fortress named All-American came trundling down a desert runway on two good wheels and a shower of sparks, her crew walking away into the sun with nothing more than ringing ears and one hell of a story.

THE END

News

CH2 – German Sniper’s Dog Refused to Leave His Injured Master — Americans Saved Him…

The German Shepherd would not stop pulling at the American sergeant’s sleeve. It had started subtle: a tug at the…

CH2 – The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men

The German officer’s boots were too clean for this part of France. He picked his way up the muddy slope…

CH2 – This 19-Year-Old Was Manning His First AA Gun — And Accidentally Saved Two Battalions

The night wrapped itself around Bastogne like a fist. It was January 17th, 1945, 0320 hours, and the world, as…

CH2 – The German Boy Who Hid a Shot-Down American Pilot from the SS for 6 Weeks…

The SS officer’s boot stopped six inches from the boy’s nose. Fran Weber stood in the barn doorway with his…

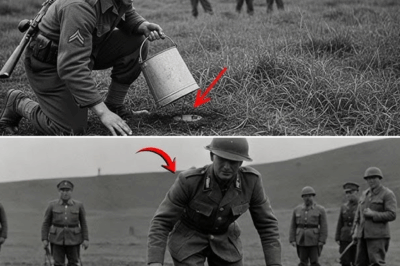

How One Private’s “Stupid” Bucket Trick Detected 40 German Mines — Without Setting One Off

The water off Omaha Beach ran red where it broke over the sandbars. Corporal James Mitchell felt it on his…

Germans Couldn’t Believe This “Invisible” Hunter — Until He Became Deadliest Night Ace

👻 The Mosquito Terror: How Two Men and a Radar Detector Broke the German Night Fighter Defense The Tactical Evolution…

End of content

No more pages to load