At 05:46 in the morning, under a low ceiling of fog rolling across the French bocage, an entire Allied corps—38,412 men, 612 tanks, 1,184 trucks, and three full artillery battalions—was marching straight into a valley that had never been meant for anything but killing.

On a map it was nothing: a narrow crease of land, 1.2 miles from ridge to ridge, with hedgerows climbing the slopes like lines on a palm. To the planners in gray uniforms twenty miles east, it was Killzone Delta, a place where math, steel, and gravity would do what bullets and courage could not.

At 05:47, Panzer elements began to creep into their attack lanes, engines muffled, armor cloaked under nets and branches. At 05:49, 172 German artillery pieces—88s, 105s, and Nebelwerfer batteries, some of them naval guns dragged inland and buried in the earth—stood loaded and ready, barrels dialed into pre-registered coordinates that overlapped like the teeth of a trap.

The fog had grounded Allied reconnaissance aircraft. The frontline commanders believed the valley was clear. The move made sense from a distance. A straight road, a shorter route, a chance to get armor and supply trucks through the hedgerow maze faster than the Germans expected.

On paper, it was efficient.

On the ground, it was suicide.

And no one in that marching column, no one in the command caravans, no one in the staff tents hunched over maps, knew it.

What they also didn’t know—not yet—was that on the ridge overlooking that valley, hidden behind the cracked boards of a half-collapsed barn, a seventeen-year-old farm girl was listening to a German radio signal so closely that she heard something every trained operator before her had dismissed.

It wasn’t a word.

It wasn’t even a sound.

It was the lack of a sound—an extra 0.88 seconds of silence—that should not have been there.

Anomalies that small did not show up in manuals. They didn’t get you promoted. They didn’t fit inside the neat boxes on Allied signal diagrams.

But that 0.88-second gap would become the key to one of the most improbable rescues of the war in Europe.

And the only reason anyone noticed it at all was because that girl had spent four years repairing fence-wire radios on her family’s farm.

The Girl Who Listened

She hadn’t planned to be anywhere near a battlefield.

Her world, before the war, had been forty-two acres of stubborn soil outside Saint-Lô. The loudest sounds most days were the wind thrumming through the wheat, the rattle of a loose barn shutter, the cough of her father’s battered tractor as it fought another season.

The farmhouse was stone and wood, patched more times than she could count. The barn smelled of hay, oil, and the faint sourness of old milk. Fence posts leaned like tired soldiers. The hens complained from their coop every time the weather changed.

What set her apart from every other farm child in Normandy wasn’t visible. It was that thing she built when she was twelve: a radio made from a cracked cigar box, scraps of copper wire stripped from the fence line, a bit of pencil lead, and two bolts pulled from an old butter churn.

It barely worked.

The little thing buzzed more than it spoke. When it did pick up a signal, it was usually a distant station, muffled and fading in and out as if it couldn’t decide whether it wanted to cross the channel. But that box changed the shape of her world.

While other girls in the village traded ribbons or practiced songs in church, she sat with the headphones smashed against her ears, eyes narrowed, listening. She learned to tell when a station across the sea changed operators by the way the rhythm of the Morse altered—same code, different hand.

By thirteen, she could hear variations in Morse rhythm the way another child might hear the difference between blackbird and sparrow. When rain was coming, she knew it from the static long before a single cloud showed on the horizon. When a storm was close, the sky hissed in the wires.

Her father shook his head, half proud, half worried.

“Radio is for the cities,” he’d mutter, though he’d linger in the doorway, pretending to fix a latch while she chased faint dots and dashes across the noise.

Her mother made the sign of the cross the first time they heard London speak through the crackling. “It’s not natural,” she whispered. “Voices from nowhere.”

The girl didn’t care whether it was natural. It worked. It connected their small patch of France to something larger, something humming and alive beyond the horizon.

Then the Germans came, and radios became illegal for civilians.

Uniformed men with hard faces and strange accents swept through the region. They posted notices on walls. They took down flags. They made lists of who owned what.

Her father hid the cigar-box set in the attic under old boards and burlap.

It didn’t stay hidden for long.

She rebuilt a new one from leftover farm scrap—a coil from a broken lantern, wire from a forgotten roll, bits of metal salvaged when no patrols were in sight. She hollowed out a grain sack and hid the set inside, the lead of the headphones disappearing into a pile of burlap any German might kick and never notice.

Her mother scolded in whispers.

“They shoot people for less,” she said. “They disappear them.”

The girl looked at her with the stubbornness that would define the rest of her life.

“If I can hear them,” she said, “they can’t surprise us.”

So she listened.

At first, she heard only distant stations pushed aside by German broadcast power. Then she began to pick up the occupier’s own transmissions: crisp, confident dots and dashes, the handwriting of the key as distinctive as any signature.

She didn’t understand the codes, but she heard the rhythm. The way certain operators rushed their sequences. The way others held a beat between groups. The way field units sounded different from static command posts.

She filled a school notebook with crude notes: times, call signs, the “feel” of the key.

When Allied bombers roared overhead at night and German guns opened up, she could tell which battery was firing by the sudden bursts of chatter on the net. When patrols moved through the area, she heard their support units checking in.

By the time the Allies landed in Normandy in June 1944, she was seventeen.

Her cigar-box radio was in its third incarnation, each version cleaner and more sensitive than the last.

The landscape changed almost overnight.

Convoys of olive-drab trucks thundered down the lane where only carts had gone before. Men in uniforms with strange patches set up tents in fields and strung wires across hedgerows. The air smelled of dust, gasoline, and sweat.

One afternoon, the girl watched a small team of signal corps soldiers set up a portable mast in the corner of their field, just beyond the barn. The corporal in charge was a stocky man with a sunburned nose. He moved with the weary precision of someone who had done the same job a hundred times in a hundred different places.

He caught her watching.

“You ever seen a real set before?” he asked in slow, heavily accented French.

She shrugged.

“Once or twice.”

He grinned and, on a whim that probably changed more than he’d ever realize, held out a pair of headphones.

“Try it,” he said.

He expected fumbling. He expected giggles, or at best, a hesitant dab at the dials.

Instead, she adjusted the gain with three quick flicks, tuned out the drift by ear, and matched two overlapping frequencies faster than he could with instruments.

He blinked.

“How did you—?”

She handed the headphones back, expression blank.

“Your left line is off by one kilohertz,” she said.

Within a week she was volunteering at the backup radio post the Americans had set up in a wooden shed that had once stored hay and broken tools.

Officially, she was a messenger assistant. She swept floors, fetched forms, boiled coffee.

Unofficially, by the second week, she was sitting in the chair in front of the receiver more often than some men whose stripes said it should be their job.

The others called her over when “something sounded strange.” They couldn’t explain why, but they trusted her ear. She was seventeen, barely a woman. Men twice her age, who’d fought in North Africa and Italy, underestimated her until the first time she corrected their timing by a fraction of a beat, or pointed out that a German signal wasn’t from a static base but from a moving column because the harmonic wavered by two cycles.

She wasn’t trained.

She wasn’t certified.

She was right every single time.

She started keeping ledgers. Not one, not two, but three thick notebooks filled with neat handwriting. Timestamps, modulation notes, idiosyncrasies. Micro-pauses in enemy traffic, odd noises under the main signal. She assigned each German operator a nickname based on their key style and logged when shifts changed.

It looked obsessive.

It was obsessive.

But in an occupation where surprise meant death, obsession with enemy patterns was sanity.

And it was the only reason that, on a fog-choked morning in June, she heard the gap.

0.88 Seconds

By 05:12 that day, the fog over the bocage had thickened into a gray curtain so dense the nearest hedgerow dissolved into a smear. Out in the fields, Allied scouts advancing ahead of the armored column could see no farther than sixty yards.

The radios were alive with routine.

Check-ins, grid references, short strings of codes that meant everything and nothing.

“Red Two, this is Red One, over.”

“Column clear to phase line Alpha, over.”

Nothing sounded unusual.

Static crackled. Men yawned and stretched in cabs while engines idled. Somewhere, a cook cursed a burned hand. Somewhere else, an officer checked his watch and wondered if the fog would lift before noon.

In the shed on the ridge above the valley, the girl sat at her console, headphones pressed over her hair, the weight familiar and comforting.

The German frequency she was monitoring had been quiet for twenty minutes. When it came to life again, at first it sounded like any other encrypted transmission: shortened bursts of dots and dashes, content scrambled by machinery.

She listened out of habit.

Then she frowned.

The gap between two groups of characters—so small another ear might not have noticed—stretched just a fraction too long.

Not a broken transmission.

Not static.

Not jammed.

Just wrong.

She glanced at the field clock nailed to the wall above the door. The red second hand ticked past the twelve. She reset her small, battered stopwatch with a thumbnail and counted silently with the rhythm of the code.

Tap-tap-tap, pause.

Tap-tap, pause.

Tap-tap-tap-tap, longer pause.

Her thumb clicked the stopwatch when the silence began and again when the signal resumed.

0.8 seconds longer than it should have been.

The number meant nothing without context. To most operators, it was nothing. Atmospheric conditions, tired fingers, a momentary glitch in a generator.

To her, it was a footprint.

Enemy units changed their gap intervals only under specific circumstances. It was something she’d deduced months earlier from listening to hours of German traffic and cross-referencing patterns in her ledgers. That slight elongation appeared only when the Germans passed certain kinds of encrypted movement orders.

The content was unreadable.

The pattern was not.

She flipped open ledger book number three, the thick one with smudged edges and bent pages. Her finger ran down a column of dates and notes until it stopped.

There.

Twelve weeks earlier.

A nearly identical gap.

She traced the entry.

“Engineer units. Mobile. Pre-Kahn ambush.”

Her throat tightened.

She checked the rest of the details on the page. Harmonic buzz, slight wobble in the lower band, faint ringing under the transmission like a distant bell.

She listened again to the tape from that morning, head bent, jaw set.

There it was: that faint metallic ring.

Most people wouldn’t have noticed it. It lived on the edge of hearing, a ghost note under the main signal, one of those things you couldn’t have pointed out if someone asked you to but that your brain recognized when it appeared.

She had chased that ring before.

It belonged to a specific German Panzer engineer company whose generator had a cracked flywheel. The crack caused a repeating vibration that translated into a tiny resonance in the transmitted signal. She had logged it the first time she’d heard it and then, like a birdwatcher recognizing a rare song in a new forest, she’d marked it every time it appeared again.

The last time she’d heard it, Canadians had walked into a valley near Caen and been slaughtered within hours.

Her hand hovered over the page.

Same anomaly.

Same cracked flywheel.

Same engineer company.

Her pulse quickened.

This transmission wasn’t just routine chatter. It wasn’t some rear guard reporting chow shortages.

It was movement.

She slid her stool back and crossed the shed in three strides, ledger in hand.

The operations desk was cluttered with forms, coffee rings, and a map pinned to a board with colored pins stabbed into it like a child’s game. A lieutenant in a wrinkled shirt sat behind it, rubbing his eyes.

“I’ve got something,” she said. Her French came out faster than she meant. She caught herself and repeated in careful English. “German engineers. The crack-wheel company. They’re moving.”

The lieutenant took the ledger as if it might explode.

He glanced at her notes, then at the map.

“We’ve got nothing on that, kid,” he said, using the English word he always used when he was too tired to remember that she understood more than he thought. “Scouts say the valley’s clear. Recon is grounded, but we’re not seeing any armor massing.”

“Listen,” she said, tapping the ledger. “The gap. The ring. It’s the same pattern as before Kahn.”

He exhaled sharply through his nose, the way officers did when they wanted a problem to go away by calling it something else.

“It’s humidity,” he said. “Atmospherics. This valley traps moisture. Everything echoes.”

“Humidity doesn’t change timing,” she said.

He gave her that tired half-smile she had come to hate.

“Good work,” he said. “We’ll keep an eye on it.”

He set the ledger aside, already reaching for another stack of reports.

She stared at him for a heartbeat, then turned without a word and went back to the receiver.

Fine.

If they wouldn’t listen, she would.

She slid the headphones on again and rewound the tape, replaying the segment one more time, this time slowing the speed.

The static roared, a familiar ocean.

The code came through again, slowed, deepened. Under it, the faint ring pulsed: one every 3.2 seconds.

Ring.

Ring.

Ring.

She checked her notes.

That interval—3.2 seconds—matched exactly the cracked flywheel’s rotation frequency she had logged months earlier.

It wasn’t just similar.

It was identical.

Engineer company present.

Engineer company meant one thing: they were laying communication lines, marking coordinates, wiring fire control nets for a synchronized artillery barrage.

Engineers did not travel alone.

They traveled with guns.

She looked up at the Allied movement schedule pinned to the wall. Handwritten times, unit designations, rough distances.

The lead battalion of the corps was scheduled to reach the mouth of the valley at 06:07.

The Germans, if they followed their Caen pattern, would let the entire first brigade enter the valley, then fire the opening salvo around 06:09—enough time for the kill zone to be full, but not so much that the column could react.

She could see it.

Infantry pinned in the open under a rain of steel. Tanks pushed forward by the weight of the vehicles behind them with no room to maneuver, road clogged by burning hulks. Casualty reports written in columns of numbers instead of names.

She had read the reports from Caen. She had studied them the way other girls studied fashion magazines.

Two thousand four hundred thirty-six casualties in under four hours.

The trap had been perfect.

This one was better.

More guns. Better concealment. Denser fog.

If she stayed silent, the ambush would unfold.

If she spoke, she would violate protocol.

Volunteers did not transmit priority alerts.

Volunteers did not touch the code key without direct orders.

Volunteers did not override chain of command.

The rules were clear.

The consequences for breaking them were, too: immediate removal from duty, reprimands, possibly worse if anyone up the line wanted to make an example.

She thought, briefly, of the corporal who had first handed her headphones and raised an amused eyebrow when she showed him his own frequency drift.

She thought of her father hiding the cigar-box radio in the attic because the Germans shot people who listened when they weren’t supposed to.

She thought of the soldiers in the trucks rumbling down the road toward the valley, men who had faces and names, even if she only knew them as voices over the radio asking for weather updates or complaining about rations.

The second hand on the field clock ticked to 06:04.

Two minutes until the vanguard reached the valley mouth.

She replayed the tape one last time, all doubt narrowed to a razor’s edge.

The anomaly pulsed exactly where it shouldn’t.

The flywheel sang its cracked mechanical song underneath.

The engineer pulses ticked out their fire control rhythm: three… pause… three… pause.

Everything pointed in one direction.

The Germans were ready.

The guns were loaded.

The valley was primed.

She inhaled.

Then she reached for the transmitter.

Eleven Seconds

The key was small and cold against her fingertips.

Her thumb trembled once, then stilled.

If she was wrong, she would be the girl who cried wolf over static, who halted an entire corps for nothing, who shattered the trust that had allowed her into the shed in the first place.

If she was right, and stayed silent, 38,412 men would march into an invisible coffin.

She adjusted the gain, retuned the frequency a fraction lower, and flipped the switch that connected her not to the main high-traffic net—crowded, monitored, and vulnerable to German intercept—but to Auxiliary Line 3.

Auxiliary 3 was the forgotten line.

An old circuit, originally installed as backup, now barely used. Most units didn’t bother to monitor it anymore. The equipment at corps headquarters was out of date, the receiver shoved into a corner rack where dust settled on its dials.

Most operators left it on for form’s sake and ignored it.

Most.

She tapped the key.

Her message was short: thirty-one characters. Eleven seconds from first transmission to last.

It wasn’t a wordy warning full of detail. There wasn’t time for that, and long messages drew more attention.

It was a timing code, a unit designation, a position hint, strung together in a pattern that anyone trained in Allied staff work would recognize as urgent.

Then it was gone.

Eleven seconds.

A single drawn-out breath.

On the ridge, the shed hummed softly.

She let her hand drop into her lap and closed her eyes.

There was nothing she could do now but wait.

The Man Who Heard

At corps headquarters, miles to the rear, the operations floor was a hive of organized chaos. Maps covered the walls and tables, littered with grease-pencil marks and colored pins. Cigarette smoke hung under the rafters. Telephones rang. Typewriters clacked. Men shouted over each other and then fell quiet at the bark of an order.

Auxiliary Line 3 sat off to the side, its receiver metal casing dented, its speaker warped.

Major Steven Hellbrook sat at a nearby desk nursing a lukewarm cup of coffee.

He wasn’t supposed to be on duty.

He was supposed to be asleep.

But he had fought insomnia since his telegraph engineer days in the civilian world, before the war, when the night shift meant overtime pay and lonely offices, and old habits died hard.

When he couldn’t sleep, he did what he had always done.

He listened.

Auxiliary 3 crackled in the corner.

Most nights—most mornings, at that hour—it carried nothing but ghost static and the occasional test pulse.

At 06:05 and a handful of seconds, it spat out a brief burst of code.

Hellbrook’s head snapped up.

He knew the timing pattern before he translated the content. He had helped design parts of it, had sat in a cramped room in London two years earlier and argued over how long a corps-level emergency code should be.

He replayed the signal, hand on the volume knob.

Thirty-one characters.

Timing block. Unit marker. A short, unmistakable phrase that made his blood run cold.

AMBUSH VALLEY STOP HOLD ALL.

He replayed it again to be sure, then slammed his coffee down so hard it sloshed over the rim.

“Who’s on Aux Three?” he barked.

Blank stares.

“Sir, nobody—”

“We just got a priority warning,” he said. “Eleven seconds. I want that on every net now.”

A captain opened his mouth to protest.

“Sir, we can’t halt an entire corps on an unsourced—”

“Yes, we can,” Hellbrook snapped. “We can and we will. If I’m wrong, I’ll write the apology letters myself. Get me the field net.”

He grabbed the nearest mic, thumbed the switch, and spoke with the clipped precision of someone who had once sent telegrams for people waiting on news of births and deaths.

“All units, all units,” he said. “This is corps headquarters. Immediate halt. I say again: immediate halt. Hold current positions. Acknowledge by call sign.”

The order shot out into the morning.

Across thirty miles of French countryside, radios crackled in tanks, trucks, and staff cars.

Some men cursed.

Some assumed it was a typo and asked for confirmation.

The confirmation came back hard and fast.

“Halt where you are,” Hellbrook repeated. “This is not a drill.”

On a narrow road half a mile from the valley mouth, the driver of Sherman C-22 slammed his boot on the brake.

The tank screeched, treads grinding, the turret commander swearing as he grabbed for balance.

Behind him, a line of armor and trucks did the same, metal shuddering, voices rising in confusion.

The fog pressed in, blank and impenetrable ahead.

Somewhere a platoon sergeant stuck his head out of a truck canvas flap and shouted, “Why the hell are we stopping? We’re on schedule!”

Then, at 06:07:18, the valley ahead of them erupted.

Killzone Delta Misfires

From the ridge, the girl felt it first as a vibration through the floorboards.

A low, rolling thump that shook dust from the rafters and made the coffee in mugs quiver.

Then the sound hit.

A wall of noise that flattened the air, a roar of 172 guns firing in near perfect unison.

The valley below disappeared into flashes and smoke.

She staggered to the doorway of the shed and clutched the frame.

White and orange bursts stabbed up through the fog, columns of dirt and rock geysering where shells hit the ground.

It was a hellish kind of beauty, symmetrical and terrible.

The German gunners had done their work well.

They had multiplied arcs and ranges, mapped the valley into a grid, and assigned each square to specific barrels. Their fire control pulses—the ones she had heard—had synchronized every lanyard pull, every trigger press.

Steel rained down on where, by every plan they had drawn up, Allied men and machines should have been.

They weren’t there.

The road at the valley mouth was empty.

The line of tanks that should have been halfway down was still stacked at the entrance, halted by a voice that had traveled from her fingers, to a forgotten line, to a sleepless major.

She watched the first barrage finish, the echoes bouncing back and forth between the ridges.

Her heart hammered.

If she’d been wrong, that barrage might have landed harmlessly in a field while she cost the Allies a momentum they couldn’t afford to lose.

If she’d been late, the shells would have scythed through steel and bone.

She had been neither.

She gripped the wood so hard splinters bit into her palm and didn’t notice.

Inside the valley, nothing lived but torn earth and smoke.

On the German side, confusion rippled.

Forward observers, their view limited by fog and the sudden smoke, peered through binoculars, expecting to see shattered columns, burning wreckage, men stumbling in panic.

They saw exploded dirt.

Their training told them to let the barrage run.

Their instincts whispered that something had gone wrong.

They fired again, though less perfectly.

The second barrage chewed the same empty ground, shifting slightly, trying to rake a target that wasn’t where it should have been.

On the ridge, Allied spotters blinked grit from their eyes, pressed phones harder against their ears, and began to talk faster.

“Counterbattery, get ready,” one shouted. “We’ve got muzzle flashes. Give me bearings. Give me anything.”

Allied radar, primitive but effective, caught the flare signatures. The fog that had hidden the German guns when they were silent now betrayed them when they spoke.

Coordinates flowed back to the gun crews behind the Allied lines.

At 06:09, thirty-eight M7 Priest self-propelled guns opened fire.

The first counterbattery salvo hit three German 88s on a forward slope. One gun vanished in a direct hit. Another flipped backward, its crew thrown like rag dolls. The third was mangled, barrel split like a peeled banana.

The Nebelwerfers, those menacing multiple-rocket launchers that had been assigned to rake the valley floor, caught the second wave. A salvo landed among their pits just as crews were loading. Rockets cooked off in their frames, turning launch positions into instant infernos.

The Panzer engineer unit that had laid out the trap scrambled to restore broken lines. Shell bursts had sliced through cables, turned carefully plotted fire nets into tangled nonsense.

Somewhere in the chaos, a battery commander shouted into a dead handset, realized he was blind, and made the worst decision of his career: he ordered his crews to fire independently, without centralized control.

Guns that had been part of a chorus broke into a discordant solo.

Their efficiency vanished.

Their positions, however, remained exactly where Allied spotters had just plotted them.

On the valley’s southern flank, the Allied corps commander stared through field glasses, jaw clenched.

He didn’t yet know why the halt order had come.

He didn’t know who had sent it, or from where.

He didn’t need to.

The evidence was in front of him: a valley that should have been a graveyard now churned under misdirected fire, the ridges exposing muzzles.

“Counterattack,” he said simply. “We’re not bleeding for this valley. They are.”

The Battle That Didn’t Happen

For the next hour, the fight belonged to the guns.

The Allies had time now.

Time they hadn’t been supposed to have.

Time to move their own artillery into better positions, to lay cables, to shift ammunition trucks out of harm’s way.

The 38 Priests fired until their barrels glowed, then rotated crews and kept firing.

Shell after shell found the German batteries that had been so carefully hidden at dawn.

Camouflage nets burned.

Gun shields buckled.

Gunners dove for cover or ran, stumbling through smoke and shrapnel.

Typhoon fighter-bombers, grounded earlier by fog, finally clawed into the sky as the weather lifted, just enough.

They spotted the thick pillars of smoke rising from the ridges and followed them, noses down.

Rockets slashed into German positions. One battery after another disappeared under explosions and flame.

German command logs from that day, later captured and translated, called it a “structural collapse of timing.”

The ambush had rested on a simple assumption: they would have at least fourteen minutes of uninterrupted firing time before Allied units could react.

They got twenty-eight seconds before the corps halted.

Another minute before counterbattery fire started.

By noon, of the original 172 German guns assigned to Killzone Delta, fewer than sixty remained operational.

In the valley, where there should have been hundreds of destroyed vehicles and thousands of bodies, there was only torn earth.

Seventeen Allied soldiers were injured that day in the sector. All minor. A few cuts from stray shrapnel. One broken arm from a truck collision when drivers braked too fast at the halt order.

Zero tanks lost.

Zero trucks destroyed.

Zero infantrymen caught in the kill zone.

The Allied corps advanced later that afternoon through terrain that should have been their grave, leaving fresh tracks in dirt that had already been churned by steel.

They seized a ridge line that German planners had expected to hold for at least another week.

Momentum—an invisible, heavy thing in war—shifted.

What had been a potential disaster became a textbook case in how to turn an enemy’s preparation against him.

The reports, when they were written days later, were full of numbers and acronyms and grid references.

In one appendix, the analysts noted that the failure of the ambush had delayed German operational plans in the sector by approximately fourteen hours as artillery units tried to regroup and reposition.

Fourteen hours.

Enough time for Allied engineers to fortify crossroads, for ammo convoys to get ahead, for infantry to dig in where otherwise they would have been running.

It was a gap in time created by another gap.

0.88 seconds of silence.

Eleven seconds of code.

Aftermath in a Shed

In the little radio shed on the ridge, when the first German barrage hit the empty valley, the girl sagged against the doorframe and let out a breath that tore at her chest.

She had broken the rules.

The regulations posted on the wall—she knew them by heart—might as well have been written in another language now.

Something inside her said, You did it.

Something else whispered, If you’re wrong, if they find out and decide it was all for nothing, they’ll send you home.

An hour later, the lieutenant came in, face ashen.

He looked at her for a long moment.

“Good instincts,” he said gruffly.

It wasn’t an apology.

It wasn’t praise.

But it was the closest he’d ever come to either.

Later that day, a messenger brought a folded note from corps headquarters.

It contained one line in careful English.

Keep listening.

No name.

No explanation.

She folded it and tucked it into the back of ledger number three.

She did not see the casualty estimates.

She did not see the maps with circles drawn in red showing where the shells had landed and where bodies would have been if the column had walked on.

She did not see the after-action graphs that compared the valley that morning with Caen, that other valley where no one had heard what she had heard and more than two thousand men had paid for it.

Volunteers didn’t get those briefings.

Volunteers swept the floor after the officers left, turned off lamps, and filed flimsy carbon copies of orders into battered cabinets.

The entry about her 11-second transmission was filed in Appendix 14B of the signal corps records, in a section marked “Protocol Violations: Operator Discipline.”

It noted that an unauthorized individual had transmitted a priority alert on Aux 3.

It added, in handwriting squeezed into the margin, “Result: corps halt—prevented casualty event. No further action.”

Then it went into a folder, and the folder went into a box, and the box went onto a shelf.

The war moved on.

So did she.

A Cigar Box and a Letter

When the guns finally fell silent months later and flags that had been banned were flown in the village square again, the girl went home.

The fields were scarred with tracks and craters, but the wheat returned. The barn roof got patched. The tractor coughed to life. Life, in its stubborn way, pushed over and around the war’s wreckage.

She married a carpenter who had kind hands and didn’t mind when she kept the radio on too loud. They had two children. They planted trees to mark their births.

She didn’t go to celebrations for veterans.

She wasn’t one.

She had never worn a uniform.

She had never fired a gun.

When people spoke of the war, they spoke of the men who had gone to the front, of those who hadn’t come back, of towns that had been leveled and built again.

Her part in it was a sliver of memory she mostly kept to herself: the smell of warm equipment, the taste of bad coffee, the way her heart had felt like it would break her ribs when the guns opened on the empty valley.

She kept the cigar-box radio.

It sat on a shelf in her bedroom, wrapped in linen when not in use.

Sometimes, when the world felt too quiet, she’d unbox it, string a coil of wire along the window frame, and listen to the static.

“The static makes the world feel honest,” she once told her daughter, who had asked why she liked “the nothing noise.”

She grew older.

Her hands stiffened, but her hearing never dulled.

She could still tell when rain was coming by the way the air changed.

She could still pick out a mis-tuned violin in a crowded room.

She could still, if she’d had the chance, have told you which operator on the old German net was about to make a mistake by the way his key stuttered.

She never spoke of Killzone Delta.

It was, in her mind, just another day she’d done what she knew how to do: listen, decide, act.

It wasn’t heroism.

It was habit.

In 1984, a British military historian sat in a reading room half a continent away, paging through declassified signal corps files.

He wasn’t looking for her.

He was studying artillery, trying to trace patterns in the way both sides had used their guns in Normandy.

He flipped through Appendix 14B almost as an afterthought.

His eyes snagged on a paragraph about an unauthorized transmission on Aux 3 that had halted a corps on June 24, 1944.

The note said the action had “prevented casualty event.”

There was no operator name.

He frowned, intrigued.

Historians are like radio operators, in a way. They listen for anomalies in the noise.

He went looking.

He cross-referenced the time stamp with battle reports from that day. He read about the valley that had been meant to be a kill zone and wasn’t. He saw the crater analysis, the planned German fire grids, the casualty estimates.

He followed the paper trail through operator logs and volunteer rosters until he found a line on one list: a local farm girl’s name with a pencil note beside it.

“Exceptional hearing. Good instincts.”

It took him six months to find her address.

He knocked on her farmhouse door, hat in hand, heart pounding harder than it had any right to for a man who spent his days with books instead of bullets.

She opened the door slowly. Her hair was gray now, pinned back in a bun. Her hands were lined, the skin thin over knuckles that had gripped more laundry than headphones in the years since.

“Yes?” she said.

He introduced himself, stumbling over the French.

When he told her why he’d come, she laughed, a soft, disbelieving sound.

“You’ve made a mistake,” she said. “I wasn’t… important.”

He opened his briefcase and laid out the documents on her kitchen table.

The appendix. The map of Killzone Delta with circles showing where shells had landed. The report from the operational research section that compared the valley to Caen.

Finally, he slid a letter across to her.

A copy.

The original sat in an archive box in yet another country.

It had been written decades earlier by a man who had marched with the corps that morning.

He had survived the war, gone home, married, had children and then grandchildren.

He had always wondered why they’d stopped outside that valley, why the order had come when it did.

He had written, “I never knew who saved us. But I’ve had forty more years with my wife, three children, and five grandchildren because someone stopped us from entering that valley. Whoever you are, thank you.”

She read the letter once, lips moving with the words.

Then again.

Then a third time.

She did not cry.

She did not puff up with pride.

Her expression was something harder to define—part shock, part recognition, part a quiet, heavy sadness that all those years, the weight of that morning had been sitting somewhere, waiting to be named.

“I didn’t know,” she said finally.

The historian nodded.

“No one expected you to,” he said. “Wars are made of a million things. Some of them are big, like tanks and generals. Some of them are small, like eleven seconds of code on a forgotten line.”

She looked down at the letter.

Her hands, those hands that had once hovered over a key in a shed on a ridge, lay flat on the table beside it.

Later, she placed the copy next to the cigar-box radio on her bedroom shelf.

She told her daughter only one thing about it.

“Don’t throw this away,” she said, resting her hand on the lid of the old set. “It helped me hear something important once.”

She didn’t explain what.

She didn’t have to.

History, as it tends to, remembered the day in terms of units and maps and casualty figures.

The official record says that on a foggy morning in Normandy, an Allied corps avoided annihilation in a valley built to kill them.

Operational research reports list 172 German guns, 38 Priests firing in counterbattery, an estimated 18,000 men who would have died in the first hour if the plan had gone as the Germans intended.

Historians talk about timing, about doctrine, about the interplay of fog and radar and reconnaissance.

Buried in one appendix, for decades, was a note about an unauthorized signal sent by a volunteer.

It lasted eleven seconds.

It carried thirty-one characters.

It violated protocol.

It saved thousands of lives.

The girl who sent it never wore a ribbon or a medal.

She never gave a speech about courage.

She lived, and worked, and aged like millions of others whose names never find their way into history books.

But for 0.88 seconds of silence, and eleven seconds of defiance, she stood between 38,412 men and the jaws of a valley that had already been measured and marked for their deaths.

Sometimes the things that change the course of a day—of a battle, of a life—aren’t the loud moments.

They’re the gaps.

The instants when someone hears something everyone else has dismissed as nothing and decides, against rules and fear and habit, to act.

On the morning at Killzone Delta, a seventeen-year-old farm girl listened more closely than anyone else.

The valley stayed empty.

The guns found only dirt.

And tens of thousands of men marched on to lives they never knew they almost didn’t have.

THE END

News

“Where’s the Mercedes we gave you?” my father asked. Before I could answer, my husband smiled and said, “Oh—my mom drives that now.” My father froze… and what he did next made me prouder than I’ve ever been.

If you’d told me a year ago that a conversation about a car in my parents’ driveway would rearrange…

I was nursing the twins when my husband said coldly, “Pack up—we’re moving to my mother’s. My brother gets your apartment. You’ll sleep in the storage room.” My hands shook with rage. Then the doorbell rang… and my husband went pale when he saw my two CEO brothers.

I was nursing the twins on the couch when my husband decided to break my life. The TV was…

I showed up to Christmas dinner on a cast, still limping from when my daughter-in-law had shoved me days earlier. My son just laughed and said, “She taught you a lesson—you had it coming.” Then the doorbell rang. I smiled, opened it, and said, “Come in, officer.”

My name is Sophia Reynolds, I’m sixty-eight, and last Christmas I walked into my own house with my foot in…

My family insisted I was “overreacting” to what they called a harmless joke. But as I lay completely still in the hospital bed, wrapped head-to-toe in gauze like a mummy, they hovered beside me with smug little grins. None of them realized the doctor had just guided them straight into a flawless trap…

If you’d asked me at sixteen what I thought “rock bottom” looked like, I would’ve said something melodramatic—like failing…

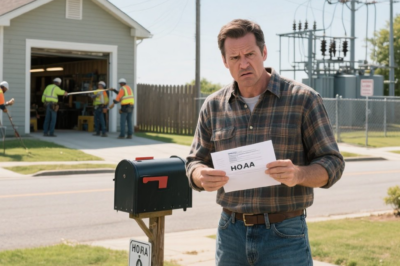

HOA Cut My Power Lines to ‘Enforce Rules’ — But I Own the Substation They Depend On

I remember the letter like it was yesterday. It came folded in thirds, tucked into a glossy HOA envelope that…

I Overheard My Family Planning To Embarrass Me At Christmas. That Night, My Mom Called, Upset: “Where Are You?” I Answered Calmly, “Did You Enjoy My Little Gift?”

I Overheard My Family Plan to Humiliate Me at Christmas—So I Sent Them a ‘Gift’ They’ll Never Forget I never…

End of content

No more pages to load