By six-eleven in the morning, July 27, 1945, the sun wasn’t even fully up but the heat was already on its way. Central Texas had a habit of giving you a preview of the day’s misery before breakfast, and that day was no different. The wheat field behind the Reed farmhouse rolled out like an ocean of dull gold, the heads heavy and brittle, bending just enough in the faint breeze to remind a man how close he was to losing everything.

Thomas Reed wiped a sleeve across his forehead and stared at the tractor like it was a mule that had just laid down in the traces.

The John Deere Model B sat squarely in front of him, green paint faded, yellow wheels dusted the same color as the wheat. It had been the best purchase of his life in 1939, back when the headlines were still about Europe and not about boys from Comanche County. Now the tractor looked as tired as he felt. The war in Europe was technically done—newspapers said “Victory” and “Surrender” and the radio kept talking about occupation forces—but none of that felt finished out here.

Not with the Pacific still burning.

Not with one son somewhere in France and the other listed as “missing” in the Philippines.

And certainly not with the damn tractor refusing to start.

He’d cranked until his shoulder throbbed and his bad knee complained, until sweat dripped off his nose and onto the dusty steel. Nothing. Just a cough, a stubborn silence, and one thin puff of black smoke that felt like the machine laughing at him.

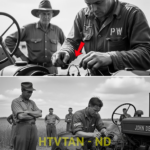

Behind him, twelve men in faded khaki shirts and trousers stood in a loose cluster, waiting. Each shirt was stenciled with two black letters—“PW”—front and back. Prisoner of War. German. They watched him with that peculiar, guarded stillness he’d come to recognize since the POW work details had started showing up last year.

They knew a lot about waiting.

Farther back, near the fence line, a U.S. Army guard leaned against a mesquite post, his rifle slung but not forgotten, cap tilted low against the coming sun. He’d already peeled off his jacket, dark sweat blossoms visible under his arms. It was going to be another furnace of a day.

“Come on, you old fool,” Reed muttered, giving the tractor’s sheet-metal hood an angry slap. “You picked one hell of a time to quit.”

He could almost feel the wheat staring back at him, reproachful. Two more days of this heat and wind and the heads would start shattering. Grain would hit the ground instead of the wagon beds, and what didn’t blow away would rot. This harvest wasn’t just about making it to next season. It was about the bank note in Brownwood, about ration stamps stretched too far, about feed for the few hogs he had left, and seed for another year he wasn’t even sure he wanted.

Six years of drought and rationing, of counting sugar crystals and bacon slices and wondering which neighbors’ windows would get the next gold star banner—six years of tight belts and tighter hearts—and now it all came down to one dead engine.

He pried the hood open again and bent over the machinery, breath coming rough, the familiar tang of gasoline and old oil rising to meet him. He knew the basics—spark, fuel, air—but this was beyond his usual “bang it with a wrench” level of expertise. He traced wires with calloused fingers, wiggled connections, checked the fuel shutoff to make sure it hadn’t been bumped. Everything looked…fine.

Fine, but not working.

“Any luck, Mr. Reed?” The guard’s voice floated over, lazy but curious.

“No,” Reed shot back without looking up. “You see any angels with wrenches, send ’em over.”

The guard chuckled. “All I got is Germans.”

Reed straightened, squinting toward the line of POWs. Some looked away when he met their eyes. A couple stared back, not defiant, just…flat. One of them, a thin man with a narrow face and a hooked nose, followed his every move with a mechanic’s focus. Reed had noticed him before. He moved like he understood tools the way a preacher understood scripture.

The man took a cautious step forward.

“Sir?” he said, the word thick with an accent but clear enough.

Reed turned fully, resting one hand on the open hood. “What is it?”

The German swallowed, choosing his English carefully. “Tractor. I…can look? Maybe fix.”

A couple of the other prisoners flicked glances at him—warnings or encouragements, Reed couldn’t tell. The guard snorted.

“You gonna let Rommel there under your hood, Mr. Reed?” he called. “Next thing you know it’ll be headed for Berlin.”

Reed’s first instinct was to wave the POW off. These men had worn the other uniform. Some of them probably still dreamed in “Heil Hitler” and goose-steps. And this machine was all he had. If this stranger stripped something, broke something he couldn’t replace…

But the wheat was there, and the clouds creeping up out of the west were already streaked dark with coming rain. And when Reed looked at the German’s face, he didn’t see a Nazi poster boy. He saw a man who looked older than his years, eyes hollowed by things that weren’t Texas sun.

“You know engines?” Reed asked.

The German nodded once. “Engines are same anywhere,” he said, with a small shrug. “I work…before war. Daimler. Aircraft engines, cars. Mechanic.”

“Name?” Reed asked.

“Carl Weber,” the man said slowly. “From Stuttgart.”

The name triggered something faint in Reed’s mind, the memory of headlines about that city burning under waves of Allied bombers. He shoved that thought aside.

“And if you break it worse?” Reed asked. “You going to pull that plow yourself?”

A flash of humor passed across the POW’s face, quick and shy.

“Then you tell captain I need no shipment home,” Carl said. “I stay here. Pull plow forever.”

The guard laughed out loud. A couple of the other prisoners did, too—the sound light, surprised, almost startled out of them. Reed exhaled hard, then stepped back and jerked his chin toward the open hood.

“All right, Carl-from-Stuttgart. Go ahead,” he said. “But I’m watching every move. And you—” He pointed at the guard. “If he runs for the fence, shoot the tractor, not him. I need the tractor more.”

“Yes, sir,” the guard replied, grinning. “Ain’t nobody out here dumb enough to run, anyhow.”

Carl approached the machine like a man approaching a skittish horse, careful, respectful. His hands bore the faint gray stains of old grease that never fully washed out. He set his fingers on the hood’s edge as if reminding himself the metal was real, not part of some waking dream.

“Magneto?” he asked, glancing at Reed.

Reed blinked. “Magneto’s over here.” He tapped the housing. “Far as I can tell, it’s getting fuel. Just no spark.”

Carl nodded and leaned in. The other prisoners shifted closer by instinct, drawn toward the familiar shape of machinery pulled apart. The guard straightened a bit, rifle still slung, eyes sharpening.

For a moment, the only sounds were the buzz of cicadas and the faint creak of wheat against wheat.

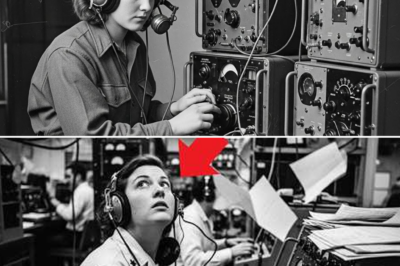

In 1945, the United States held more than four hundred thousand German prisoners of war scattered across camps from New Jersey to California. Almost fifty thousand of them were in Texas alone—brought over in convoys watched by destroyers, processed through barbed-wire compounds in places like Hearne, Hereford, and Camp Bowie near Brownwood, then parceled out in work details to do the jobs American hands had left behind.

Thomas Reed hadn’t asked for prisoners. The War Manpower Commission had. The local county agent had shown up one dusty afternoon in ’44 and made his pitch with a pamphlet and a tight little smile.

“Look, Tom,” the man had said, “you can’t bring in that crop alone. Most of the boys are gone, and the few that are left are working three farms each. The Army’s got these Germans under guard, under the Geneva thing, and they’ll pick up part of the tab. They get paid eighty cents a day, same as if you hired local, but Uncle Sam handles that. You just feed ’em lunch, stick to the rules, and sign the papers.”

At first the idea had turned Reed’s stomach. His own sons were in uniform. Henry, the oldest, had written from France in a cramped script about hedgerows and church steeples and a kind of mud that soaked into your bones. Mark, the younger one, had shipped out to the Philippines and then just…stopped writing. A telegram had come instead. “Missing in action,” it said, as if a boy could be misplaced like a tool.

Now this same government wanted him to shake hands with the enemy at his own fence line and put tools in their hands.

But wheat didn’t care about flags, and banks didn’t take ideology as payment. The first work detail had arrived in a deuce-and-a-half truck at dawn one morning, stepping down one by one, guarded by a kid from Ohio who looked like he should still be in high school.

The Germans had been quiet then, too. Eyes down, faces tight. They were issued canvas work gloves and wide-brimmed hats for the sun and sent into the fields with instructions sharper than any scythe: “You do your job, you follow orders, and you don’t start nothing. You start something, you’ll wish the war had killed you instead.”

That had been almost a year ago. They’d been back a dozen times since, different faces in the same khaki uniforms, barbed-wire patches sewn on where rank used to be. Reed still thought of them as strangers, not by name. He knew they loved coffee if they could get it, hated the taste of black-eyed peas, and sometime during the long rows their shoulders straightened as the rhythm of work took over and whatever they’d carried from Europe loosened its grip for a while.

But he’d never let one of them inside his tractor’s guts.

Until now.

Carl Weber found the cracked ignition wire like a doctor finds a bad bone.

He ran his fingers along the line from the magneto to the distributor, bending it gently, feeling for give. When he hit the fracture, the insulation split open, revealing a thin, corroded bite in the metal core. He pressed it back together, and the wire flexed limply like an old man’s wrist.

He frowned. “You have new wire?” he asked.

“No,” Reed said. “Nearest parts I don’t already have are twenty miles away and the store’s not even open yet. Even if it was, we ain’t got time to drive there and back.”

Carl’s eyes flicked around the yard. Barn. Tool shed. Fence. Wheat. Sky. Then his gaze settled on the strands of barbed wire running in a dusty line behind the guard, metal catching the new light.

He pointed. “That. Fence wire. I can…borrow a little.”

The guard barked a laugh. “Ha! You hear that, Mr. Reed? Kraut wants to fix your John Deere with barbed wire. That’ll be something to tell the boys back home.”

Reed narrowed his eyes. “You can’t just tie barbed wire in for insulation,” he said. “You’ll short out the whole thing. Or fry the magneto.”

“I don’t tie like that,” Carl said calmly. “I make…how you say…brace. Wrapping. Force wire together tight. Current,” he added, tapping his own chest with two fingers as if mimicking electricity. “Needs only little path. I give it path. And nail. For contact.”

“A nail,” Reed repeated slowly. “You’re gonna fix my tractor with barbed wire and a nail.”

Carl met his eyes, steady as a level.

“Yes,” he said. “Unless you have better idea.”

Reed didn’t. What he had was a field aging toward uselessness and thunderheads thickening in the hazy west like a promise. He jerked his head toward the fence.

“Sergeant,” he called to the guard, “you mind if he clips a piece?”

The guard shrugged, pushing off the post. “So long as nobody’s running through the gap,” he said. “Don’t see why not. Wire’s Army’s problem. Tractor’s yours.”

Reed dug in his pocket and came up with a pair of old pliers, the handles worn smooth where his thumb had rested for twenty years. He handed them to Carl.

“Fine. Take just what you need. This better be one hell of a trick.”

Carl took the tool reverently. “Is stupid trick,” he said with a faint, crooked smile. “But sometimes stupid works.”

He walked to the fence, the other prisoners parting to let him pass. They watched with hooded eyes as he knelt at the bottom strand and worked the pliers with short, economical movements. No wasted effort. The wire snapped with a sharp, metallic twang. The guard shifted his feet but didn’t raise his rifle.

“Don’t go making a habit of that,” he said mildly. “Army hates it when the cows start voting with their feet.”

Carl didn’t answer. He was already walking back, looping the length of barbed wire loosely around one palm. He sat on the tractor’s running board and leaned in again, eyes narrowing in concentration.

First he used the pliers to strip back the brittle insulation around the broken section of the original ignition wire, exposing clean metal on each side. Then he took the fence wire and, with hands that remembered a hundred other repairs in a hundred other shops, bent it carefully around the wounded joint, twisting it into a tight spiral that bridged the gap and wrapped the wire like a steel bandage.

He left the barbs facing outward, clear of everything else.

“Need nail,” he said. “Small. Straight.”

Reed barked a short laugh, half disbelief, half nerves. “You already took my fence. Now you want my barn, too?”

He strode toward the weathered building anyway, boots kicking up little ghosts of dust. Inside, the barn was cool for the moment, still smelling of hay and horses even though both were in short supply now. He plucked a short, straight nail from a coffee can on the workbench and headed back.

Carl rolled the nail between his fingers, then pressed it into the magneto coil’s fractured contact point, using the barbed wire spiral to cinch it tightly into place. Every motion was precise, deliberate, like someone tying a fly or soldering a fragile circuit.

The other Germans had edged closer, their usual detached reserve eroded by curiosity. They spoke quietly among themselves in German, the consonants heavy and unfamiliar to Reed’s ear, but he didn’t hear hostility in it. Just commentary, the same kind of muttering that local farmers did over the hood of a pickup.

“Was macht er da?” one asked.

“Improvisiert,” another replied. “Wie immer.”

The guard scratched at his jaw. “I’ll be damned,” he said under his breath. “If that thing turns over I’m writing home about it.”

Carl tightened the last twist and tugged gently to test his work. The makeshift joint held, the nail wedged snug in its new duty as a contact. He exhaled, wiped his palms on his trousers, and stepped back from the machine.

“Try now,” he said.

It was six forty-seven by Reed’s watch. Thirty-six minutes since he’d hit the cracked wire with his knuckles and muttered a curse. Thirty-six minutes that felt longer than some of the years he’d spent on this farm.

He wrapped his hand around the starter crank, feeling the familiar weight and the tremor in his own arm. He shot a glance at Carl.

“You sure about this?” he said.

“No,” Carl answered honestly. “But we will see.”

Reed set his feet and pulled.

The engine turned, coughed once, and fell silent.

He pulled again. A cough, a wheeze, a puff of black smoke that crawled out of the exhaust pipe like an insult, then faded.

Third time, he told himself. Third time’s the charm or the curse.

He pulled a third time, every muscle from shoulder to spine tightening with the effort. The crank spun, the engine rolled…and caught.

The sound started as a stumble, an uncertain clatter, and then smoothed out into a deep, steady rumble that vibrated through the tractor’s frame and into the ground beneath their boots. Exhaust puffed in a strong, regular rhythm. The flywheel spun clean.

For three long seconds, no one moved.

Then the guard whooped, a rough, delighted shout that broke the spell. One of the prisoners slapped Carl on the back. Another threw both arms up and yelled something that sounded very much like “Jawohl!” The rest laughed, smiled, clapped hands, the restraint cracking just a little.

Reed just stared. The machine that had refused him, mocked him, sat dead and stubborn for two days now idled as if nothing had ever been wrong. The barbed wire and the nail were hidden under the hood, but in his mind’s eye he could see them, holding that lifeline of electricity together.

He swallowed, throat suddenly dry.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he said softly. “You crazy son of a gun actually did it.”

Carl ducked his head, a shy grin pulling at one corner of his mouth.

“Stupid trick,” he said. “But like I say…sometimes stupid works.”

Reed let out a breath that felt like it had been stuck in his chest since the telegram came about Mark. It wasn’t that big, not compared to missing sons and dying towns and ruined cities across the ocean, but it was something. Something that worked. Something fixed.

“Get up on the wagon!” he yelled to the prisoners, his voice suddenly loud again. “We’re burning daylight. We got two days, maybe less, to get this wheat in before that storm hits, and I’ll be damned if we let it rot.”

The men scrambled into motion with an energy that surprised him. Whatever else they were, they were people used to hard work. They clambered onto the wagons, grabbed pitchforks, fell into place.

As Reed pulled himself up onto the John Deere’s metal seat, he looked down at Carl.

“You ride with me,” he said. “I want you where I can find you if that thing decides to die again.”

Carl nodded and stepped onto the small platform beside the tractor seat, steadying himself with one hand on the fender. The guard trudged back to the fence line, settling his cap a little lower as the sun flexed its strength.

The tractor rolled forward, tires crushing the dirt, the engine humming, the field of gold opening itself in front of them like a fragile promise.

They worked until the sky went from pale pink to white-hot blue and then to the washed-out gold of late afternoon. The wheat hissed and whispered as it fell, the wagons filled, emptied, filled again. Sweat soaked through shirts, trickled down spines, stung eyes. Dust coated teeth, turning spit to mud.

By midmorning, Carl’s “stupid” repair had earned a new name.

“The wire trick,” the guard called it, leaning on his rifle as he watched Reed release the clutch and start another pass. “Hey, Herr John Deere, that barbed wire thing holding up?”

Carl answered without taking his eyes off the row. “Is only lazy current,” he said. “Tell it where to go, it goes.”

That got a laugh from several directions, English and German blending for one brief moment into something less divided.

At lunch, they ate sitting in the narrow shade of the wagon, the guard perched just far enough away that his rifle could see everything. Mrs. Reed brought out cornbread and beans and coffee in a big enamel pot. She ladled it into tin cups for the prisoners with the same brisk efficiency she used for the guard, her husband, her own children. The Geneva rules said the POWs had to get the same food as American enlisted men, and she took rules seriously, even when they applied to men who had once worn a swastika on their sleeves.

Carl cradled the cup in both hands, inhaling the coffee’s sharp smell before drinking. It was weaker than what he remembered from home, but after camp chicory and thin substitutes it tasted like a gift.

Reed watched him over the rim of his own cup.

“You ever think you’d end up fixing some Texas farmer’s tractor?” he asked.

Carl smiled faintly. “No,” he admitted. “I learn English in school, you know. We think we use for reading American magazines, maybe talking to customers sometimes. Not for…this.” He gestured, taking in the wheat, the sun, the wagon, the guard, the letters “PW” stamped on his own chest.

“You were a mechanic back home?” Mrs. Reed asked, surprising everyone, including herself. She rarely spoke to the prisoners beyond “Food’s ready” and “Don’t track mud in the kitchen yard.”

Carl nodded. “Ja. Cars, sometimes trucks. Before war I think maybe get bigger shop. Then…” He lifted his fingers, letting them tumble down like little falling bombs. “Then everything change.”

There was a moment of quiet. The cicadas filled it.

“How old are you?” Reed asked.

“Twenty-seven,” Carl said.

“Too damn young,” Reed muttered, almost to himself. “My boy Henry’s twenty-three. He’s in France still, last I heard.”

Carl’s expression shifted. “He writes to you?”

“Sometimes,” Reed said. “When he can. Army don’t exactly give them a desk and stationery and tell ’em they got to keep their old man posted.”

“And other son?” Carl asked cautiously. “Guard, he say…”

The guard looked up sharply, but Reed waved him off.

“Missing,” Reed said flatly. “In the Philippines. I don’t know if that means he’s dead, or sitting in some camp over there like you are here, or somewhere in between. Army says ‘missing in action’ and expects that to cover it.”

Carl stared at his beans, appetite suddenly dulled. In his mind’s eye he saw other camps, other fences. Some with Geneva posters in three languages reminding guards how to treat prisoners. Some without.

“In war,” he said quietly, “there is much between. Not only alive, not only dead. Many…what is word…shadows.”

Mrs. Reed cleared her throat. “Well,” she said, standing, “shadows or not, these plates won’t wash themselves. Tom, if that tractor of yours keeps running, I suppose we’ll get this harvest in yet.”

Reed looked toward the horizon. The clouds there were darker now, the edges sharp, like bruises blooming against the far sky.

“If it keeps running,” he agreed. “We’re going to keep at it till we can’t see.”

They did, too.

By the time the first low growl of thunder rolled across the plains, the last wagon had been backed into the barn. The grain bin was fuller than it had been in three years. The tractor’s engine finally chugged to a halt, hot metal ticking softly as it cooled. Reed climbed down from the seat, joints protesting. The German prisoners sat on the wagon’s edge, chests heaving, shirts plastered to their backs with sweat and grim satisfaction.

“Good work,” Reed said, surprising himself again. “All of you. Couldn’t have done this without you.”

One of the older prisoners gave a small nod, as if accepting a simple fact rather than thanks. Carl just looked toward the west, where the clouds were now stacked high and heavy, the leading edge of the storm dragging curtains of rain under it.

“No,” he agreed. “You could not.”

The guard checked his watch. “Truck’ll be here in about an hour to haul ’em back to camp,” he said. “You want ’em to wait out the storm in the barn?”

Reed glanced toward the farmhouse, where a thin plume of chimney smoke said his wife was already thinking about supper.

It had been a long time since he’d sat at the table with more than his immediate family. A long time since the kitchen had held more conversation than the scrape of cutlery and the faint, worried whisper of prayer. There were rules about fraternization, of course. Guidelines about how close you were supposed to get to the men behind the PW stencils.

But there was also something else—a weight in his chest that felt, for once, slightly lighter. Today had gone right, for a change. Somebody who was supposed to be his enemy had put his hands into the heart of his livelihood and pulled it back from the brink.

He chewed on that for a moment, then looked at the guard.

“What’s the regulation say about feeding ’em in the house?” he asked.

The guard shrugged. “Regulation says you gotta feed ’em something,” he replied. “Don’t say where. Camp commander probably wouldn’t like it if you sat ’em at the family table, but I ain’t in the habit of writing essays about every farmer’s supper arrangements.”

“So that’s a ‘do what you want, I’ll look the other way’?” Reed asked.

“That’s a ‘your risk, sir,’” the guard said with a half-smile. “You invite ’em in, you vouch for ’em.”

Reed glanced at the men—tired, dusty, young and old, faces lined by more than just Texas sun. He thought of Henry, somewhere in ruined towns with names he’d never be able to pronounce properly. Of Mark, whose name lived now only on a telegram and a folded flag in the hall closet.

He thought of the barbed wire wrapped around that ignition wire, holding current like a handshake.

“All right,” he said finally. “We’ll eat in the house tonight.”

The kitchen table at the Reed farmhouse was long and scarred, its surface bearing marks from a thousand meals and a hundred homework sessions and one or two awkward family arguments cut off halfway when someone knocked at the door. Tonight it bore something else: a line of faces that would have looked more at home on the other side of the ocean.

Mrs. Reed had hesitated only once. Then her practical nature had taken over. Men were men. Men who had worked in her fields all day in that heat deserved beans and cornbread at least as much as any local boy. She put extra plates on the table, moved the jar of wildflowers to the mantle, and told her youngest to make sure the forks all matched.

The Germans filed in two by two, hats in their hands, eyes flicking around as if soaking in every detail. The ticking wall clock, the faded Bible on the shelf, the photograph of Henry and Mark in their uniforms perched beside a ceramic rooster.

The smallest Reed child—a boy of six with a cowlick that refused discipline—stared openly. “Daddy,” he whispered, tugging at his father’s sleeve, “they don’t look like the pictures in the magazine.”

“What pictures?” Reed asked, though he knew.

“In the paper,” the boy said. “The ones with the devil horns and the fangs.”

Reed’s gaze slid over his guests. One had a crooked nose that had been broken and never set right. Another had a gap in his teeth, another a scar along his jaw. None had horns or fangs.

“Real life’s different than pictures,” Reed said quietly. “They’re just men, Billy. Same as anybody else.”

The guard took up a position by the door, rifle leaned against the frame within easy reach. He looked almost as uncomfortable as the prisoners, unused to being inside a stranger’s home in anything but an official way.

They took their seats—Reeds at one end, guard at the side, POWs filling the length. Carl sat opposite Reed, hands folded loosely on the table, posture stiff, as if he were afraid to knock something over by accident.

Mrs. Reed served cornbread, beans flavored with a hint of bacon grease, and black coffee strong enough to make spoons stand up. It wasn’t fancy, but it was hot and filling.

For the first few minutes, the clink of fork on plate and the occasional murmur were the only sounds. The Germans ate carefully, as if afraid someone might change his mind and snatch the plates away. The Reeds ate a bit more quickly than usual, the presence of strangers making every bite feel like part of a performance.

Then Billy tumbled his toy truck onto the table.

It was a little metal thing, chipped red paint, wooden wheels, one axle slightly bent so that it always listed to one side. It skidded across the tablecloth and bounced against Carl’s cup.

“Sorry,” Billy whispered, eyes wide. “It always does that.”

Carl picked up the toy, turning it over in his fingers. He touched the bent axle with the gentle assessment of a man evaluating a problem.

“This is easy,” he said, half to himself.

Reed tensed. “You break that, my wife’ll have your hide harder than the U.S. Army ever will.”

Carl smiled faintly. “No break,” he promised. “Fix.”

He set the truck down, placed one thumb against the warped wheel, and with a small, practiced twist, straightened the axle just enough. The wheel spun more evenly now. He rolled the truck back to Billy, who caught it and then set it down on the table, eyes widening as it trundled in a nearly straight line.

“Daddy!” Billy said. “He fixed it!”

“Guess he did,” Reed said, something loosening in his chest again.

“Thank you,” Billy said solemnly to Carl.

“You are welcome,” Carl replied. “I fix big engines, little trucks…all same.”

The guard chuckled. “You’re gonna have a business waiting when you get back home, Weber,” he said. “People’ll line up for your stupid wire tricks.”

One of the older Germans spoke up, his English heavily accented but understandable. “Is good to feel useful,” he said. “Even with…this.” He tapped the PW stencil on his chest with two fingers.

Conversation, once started, began to find its own path, wandering between English and halting German and the universal language of names and places and shared complaints.

Reed talked about the early years of the war out here—about gasoline rationing and rubber tires so thin you could see daylight through them, about the way the local dance hall went from crowded to half-empty over the course of a summer as boys joined the Army. Mrs. Reed shared the story of driving into town the day the news about Pearl Harbor had hit, the way people had stood in little clusters on the sidewalk around radios, faces pale, hands clenched.

Carl spoke quietly about Stuttgart, about growing up with streetcars rattling by and the smell of the river when the wind blew just right. He talked about working in the Daimler factory, about engines that had to be precise to a hair’s width because the planes they went into flew too fast and too high for anything less. He mentioned the first time the air raid sirens had gone off, how he’d almost laughed from nerves, how nobody laughed later when the sirens became as regular as church bells.

“What was it like?” Billy asked. “With the bombs.”

“Billy,” Mrs. Reed said sharply. “That’s not—”

“No, it is okay,” Carl said gently. He thought for a moment, searching for words that wouldn’t paint too much. “Is like thunder,” he said finally. “Only the thunder is below you, coming from the ground. And the light…very bright. After, there is much dust. You cannot see, you cannot breathe. But then, you do. Or you do not.” He shrugged. “Many do not.”

One of the POWs at the far end of the table cleared his throat. “My village,” he said, in heavily accented English, “is gone. No map has it now. Just…field.”

Mrs. Reed’s hand tightened around her fork. Across the table, the photograph of Henry and Mark gleamed faintly in the lamplight.

“I’m sorry,” she said, surprising herself again.

“So am I,” the man said simply.

Reed studied their faces, one by one. Some were probably hard-core Nazis. Statistics said they had to be. Some had likely done things he didn’t want to imagine. But sitting at his table under his roof, eating his beans, talking about their mothers’ kitchens and lost streets…they looked less like the caricatures in the newsreels and more like the farmhands he’d hired in the Depression.

The war, he realized, had a way of flattening people into symbols. This table, tonight, was doing the opposite.

Later, after the plates were cleared and the lamps turned down, Reed walked them all back out to the yard. The rain had started, fat drops pattering on the hard-packed earth, raising that smell of wet dust that always made him think of childhood. The truck from Camp Bowie rumbled up the road, headlights cutting long beams through the dark.

The prisoners climbed into the back one by one, ducking under the canvas, faces ghostly in the brief light. Carl paused at the tailgate and looked back toward the barn, where the John Deere sat under shelter, the repaired wire hidden, the harvest safe.

“Thank you,” he said to Reed, the words careful. “For…today. For trusting.”

Reed shifted, uncomfortable under the weight of gratitude from someone he was supposed to hate.

“Thank you for fixing my tractor,” he said gruffly. “Don’t think I’ll forget that trick anytime soon.”

Carl hesitated, then offered his hand.

It was a risk. A risk for him, in case some officer later decided he’d crossed a line. A risk for Reed, in case someone in town decided shaking hands with the enemy meant he’d forgotten which side he belonged to.

Reed took it anyway.

Carl’s grip was firm but not crushing. His palm was calloused, familiar.

“Peace,” Carl said quietly, in English. “Maybe, sometime, it will come.”

“Maybe,” Reed said. “In the meantime, we fix what we can.”

The guard cleared his throat gently. Carl climbed into the truck. The canvas flapped closed. The engine growled, gears clunked, and the vehicle pulled away, taillights glowing red through the rain.

Reed stood under the drizzle until the truck’s rumble faded, listening to the ticking of cooling metal in the barn, the rush of water in the gutters, and the faint, steady beat of his own heart.

Two months later, the war ended everywhere.

Japan surrendered after words none of them had heard before—Hiroshima, Nagasaki—suddenly became part of conversations in the feed store and the barber shop. The newspapers printed pictures of mushroom clouds and cities turned to ash. Some men cheered. Some went very quiet. The gold stars in windows didn’t change; they just stopped multiplying.

The Army began sending prisoners home. The big camps emptied slowly, like bathtubs with a leaking plug. Convoys headed east, then east again, then out across the Atlantic. Some prisoners were glad to go. Some feared what they’d find on the other side of the ocean more than anything they’d faced behind American barbed wire.

One crisp October morning, Reed got a letter from the camp liaison officer out at Bowie. Typed on Official United States Government Letterhead, it notified him—courteously and without much sentiment—that the work details would be discontinued after that month. The last of the Germans would be shipped out.

He read the letter twice, then folded it and slid it into the drawer where he kept his seed catalogues and his boys’ letters.

On a gray afternoon not long after, an olive-drab truck rolled up his drive one last time. The guard was a different man now, older, with tired eyes. The prisoners in the back were older, too, in a way that had nothing to do with birthdays.

Carl was among them.

He stepped down from the tailgate with his duffel over his shoulder, the letters “PW” on his shirt faded from many washings. Reed met him halfway, boots thudding on the packed earth between house and barn.

“They say you go soon,” Reed said. “Back to…Stuttgart, was it?”

“Yes,” Carl said. “Transport ship. New York, then sea. They say…country is not like before. I believe them.”

Reed nodded. “We’ve heard. Radio says it looks like somebody scraped half of Europe off the map and started over.”

Carl’s gaze drifted toward the barn. “Tractor still works?” he asked, with a flicker of that earlier grin.

“Starts on the first crank most mornings,” Reed said. “I left your stupid wire trick in there. Figure if it ain’t broke…”

“Don’t fix,” Carl finished.

They walked to the barn together. Inside, the John Deere sat where it always had, slightly off-center, as if it had come in too fast one day and never been nudged straight. Reed flipped open the hood. The barbed wire wrapped around the ignition wire still gleamed faintly, rust just beginning to bite at the edges. The nail was in place, stubborn as ever.

Carl reached out and touched the repair lightly, fingertips resting on the crude splice like a priest touching an altar.

“I make many fixes in my life,” he said softly. “This one…maybe most important.”

Reed’s throat tightened. He cleared it brusquely.

“Hang on,” he said. “Got something for you.”

He rummaged on a shelf, pushing aside a jar of bolts and an old carburetor, until he found the photograph he’d had the man from town take. He brushed a smear of dust off the front and handed it over.

It was a simple picture: the Reed family standing in front of the John Deere, wheat field behind them. Thomas, shoulders squared. Mrs. Reed, hands resting on Billy’s shoulders. An empty space where one might imagine Henry and Mark standing, if the timing and the war had been kinder. And beside the tractor, slightly apart but clearly part of the group, stood Carl in his PW shirt, hands at his sides, expression caught between solemn and hopeful.

“For you,” Reed said. “So you don’t forget how to fix things properly.”

Carl stared at the photograph, eyes drinking in every line. His own image looked strange to him—thinner, perhaps, than he felt, but more solid than he’d been when he first stepped off the train at Camp Bowie.

“Thank you,” he said. His voice caught. He swallowed and tried again. “Thank you, for letting me be…what is word…more than prisoner. For letting me feel useful again.”

Reed shrugged, uncomfortable with praise.

“You earned it,” he said. “Besides, that stupid wire trick saved my farm. Bank was breathing down my neck. Without that harvest, you might’ve been shipping me to a camp somewhere.”

Carl laughed, a short, surprised bark of sound.

“I do not think Geneva have article for American farmers,” he said. Then, more seriously: “If you ever come to Germany…” He trailed off, glancing toward the horizon like he could see across the ocean. “There will be…how you say…coffee. And workbench.”

Reed stuck out his hand again.

“You get your country put back together first,” he said. “Maybe someday.”

They shook, firmly, once more.

The guard’s voice cut across the barn. “All right, fellas, time to load up. Boat won’t wait for you.”

Carl slung his duffel back over his shoulder, photograph held carefully in his other hand. At the barn door, he paused and looked back one last time at the John Deere, at the barbed wire glinting under the dull light.

“Peace,” he said again.

Reed nodded. “Peace.”

The journey home took thirty-one days.

Carl stood at the ship’s rail as New York’s harbor receded, the Statue of Liberty a ghostly shape in the mist. He’d never imagined he’d see it at all, let alone from the deck of an Allied troopship heading the wrong direction. Men clustered in knots on the deck, talking about home and bread and their mothers’ faces, about the fear that no longer having a home to go to was worse than any prison.

In Bremerhaven, the shoreline looked like something from another world. Cranes leaned at crazy angles, their steel bones exposed. Warehouses were smashed blocks of concrete and twisted rebar. The air tasted like ash and coal dust.

They disembarked in silence, boots crunching on broken glass. Trains took them inland, through landscapes that looked as if a giant child had stomped his way across them in a temper. Towns were flattened, roofs gone, streets choked with rubble. In some places, small flags or bits of cloth fluttered from broken windows, signals of life in the wreckage.

Stuttgart was worse.

The factory where Carl had once spent his days tightening bolts to precise torque values was a blackened shell. The brick walls still stood in some places, but the roof was gone, the interior an unrecognizable heap of metal and ash. The familiar hum of machinery was replaced by the hollow drip of water and the echo of his own steps.

He found where his parents’ apartment building had been by memory and the shape of the street, not by any remaining label. Neighbors—some familiar, some new, all thinner than they ought to be—told him there had been a raid in March of ’44. The building had taken a direct hit. No survivors.

For a while, Carl wandered.

He found work where he could—hauling bricks, shoveling debris, trading a day’s labor for a half-loaf of bread. He slept in a crowded shelter at first, then in a room above a butcher’s shop that had only half a roof but four walls and a door. Time blurred, measured not in days or months so much as in gradually shifting colors—from gray despair to a more tentative, fragile hope.

He gravitated back to machines as soon as he could. People still needed bicycles to get to the places where food appeared, needed carts to haul rubble, needed generators to power the few lights that could be coaxed back on. He fixed what he could with what he had—old parts salvaged from the ruins, twisted metal straightened and given new purpose.

Eventually, he rented a small corner of a building that still stood mostly upright, its windows patched with scavenged glass. He scrubbed the walls, swept the floor, and hung a sign outside on two rusty nails:

Weber Maschinenservice.

Weber Machine and Service.

Inside, above his workbench, he tacked up one photograph.

The Reeds, the tractor, the wide Texas sky.

When customers asked about it, he would smile and say, “A friend, very far away, who taught me something important about fixing things.”

He didn’t tell them everything. Not about the hopeless morning and the barbed wire, not about the cornbread and the little boy’s toy truck, not about the way a handshake had felt like a bridge built over a very deep chasm. But the photograph watched over him all the same.

Years passed. The city rebuilt itself in fits and starts. New buildings rose where old ones had fallen. Children played among foundations that had once been craters. People talked less about the war and more about the price of bread, the availability of soap, the strange American music coming over the radio.

Carl grew older. His hair thinned. He gained a small belly from sitting more and lifting less. His hands remained steady, though, able to coax a stubborn engine into motion with the same patient stubbornness he’d shown that morning on the Texas farm.

One day in the spring of 1947, he sat at his bench, looking at the photograph, and thought about the harvest.

He wondered if the tractor still ran.

On a scrap of paper, he began to write, his English rusty but serviceable:

Dear Mr. Reed,

I hope the harvest was good this year…

He told them, in simple words, that he was home. That Germany was broken but alive. That sometimes, when he fixed engines, he could still hear the wind moving through Texas wheat. That he was grateful for the day they’d trusted him with their machine and, more importantly, with their table.

He signed it “Carl Weber” and added the address of his little shop. He put the letter into an envelope, addressed it carefully to the Reed place in Texas, and walked to a post office that had only half its original bricks but all of its stubbornness.

Months later, in May of that year, the letter arrived at the Reed farm.

Mrs. Reed found it in the mailbox, the foreign stamp catching her eye. She brought it inside, wiped her hands on her apron, and called her husband.

“Tom,” she said. “You better come see this.”

He opened it at the kitchen table, Billy watching with big eyes. The words were a little crooked, the grammar odd in places, but the meaning was clear. When he reached the line about the Texas wind, his throat tightened.

“Can I see?” Billy asked.

Reed handed the letter to him. The boy traced the loops and lines with one finger.

“He remembers us,” Billy said, wonder in his voice.

Mrs. Reed framed the letter and hung it on the mantle beside the picture of Henry and Mark.

Over the years, the ink faded some. The paper yellowed. But the weight of the words never did.

Time moved in its unhurried, relentless way.

Camp Bowie was torn down eventually, its barracks and fences dismantled. Where the razor wire had once caught the light, new housing developments rose, each with its own neat rows of mailboxes and carefully tended lawns. People shopping at the grocery store on Saturdays no longer thought about the days when POW work details had walked down Main Street under armed guard, passing in front of the hardware store and the druggist’s and the barbershop.

A few remembered, though.

In barns and sheds across central Texas, the legacy of those work details outlasted the fences. Tractors with odd welds on their frames that never seemed to crack. Gearboxes that shifted smoother than factory-fresh ones. And every now and then, under a layer of dust and chaff, a length of barbed wire that had been repurposed into something other than a barrier.

In 1984, a journalist from Dallas drove out into that country with a tape recorder, a notebook, and an idea. He’d heard from an uncle about German POWs picking cotton and chopping wood, about a few who had married local girls and come back after the war with green cards and thick accents. He wanted to write about it—a story of a time when America had kept its enemies behind fences but also at workbenches and kitchen tables.

He used old county records and thicker older phone books to find names. One of them was Thomas Reed, Jr.—Billy, long since grown, now with rough hands of his own and hair that had gone more silver than brown.

The journalist stepped out of his car into the same yard where the truck from Camp Bowie had once parked. He wiped sweat from his forehead and walked up to the porch, where a man in his mid-forties—Reed’s grandson—leaned against the rail.

“I’m looking for Mr. Reed,” the journalist said. “I heard he might have a story about a German POW and a tractor.”

The younger man smiled. “You want my daddy,” he said, jerking his chin toward the barn. “He’s out back. Still tinkering with that old Deere.”

Inside the barn, Thomas Reed Jr. stood beside the John Deere Model B. Its paint was more rust than green now, its tires replaced twice, its seat showing the scars of a welding repair from the sixties. But the engine block was the original. And under the hood…

Under the hood, the barbed wire was still there.

The journalist asked his questions. Reed Jr. answered in a slow drawl, the words coming easier once he started talking. He told him about that July morning in 1945, about the way his father had cursed and the POW had stepped forward and the guard had laughed. He showed him the framed letter still hanging on the mantle, the photograph of the family and the enemy mechanic standing together in front of the wheat.

Then he led the reporter back to the barn, patted the hood of the tractor, and opened it up to reveal the repair. The wire was rusted now, but the shape of the spiral was still clear, the nail still wedged in place.

“You ever think about replacing it?” the journalist asked.

Reed Jr. shook his head.

“Nope,” he said. “Dad always said, ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’ And I figure if something made by your enemy and a bit of scrap can hold this long, you don’t mess with it.”

He grabbed the crank and gave it a pull.

The engine coughed, sputtered, hesitated—for a second, the barn held its breath—and then roared to life, settling into that same deep, familiar rumble.

Reed Jr. smiled, his eyes distant for a moment, seeing not the worn boards of the present but the younger face of his father and the thin German POW with the mechanic’s hands.

“Still works,” he said quietly. “Guess he fixed more than just metal that day.”

Across the ocean, in Stuttgart, a small workshop went quiet in 1972.

Carl Weber died in his sleep, according to his neighbors. His nephew came to clear out the shop, sorting through drawers of bolts and piles of manuals, packing away wrenches that had worn grooves into his uncle’s palms. The sign—Weber Maschinenservice—came down with a reluctant creak of nails.

Above the workbench, he found the photograph.

He took it down carefully, flipped it over, and saw there was writing on the back in his uncle’s neat, deliberate German script.

“Frieden beginnt mit Vertrauen,” it said.

Peace begins with trust.

The nephew studied the faces in the photograph—the American family, the German mechanic, the tractor behind them, the open sky above. He didn’t know the full story, but he could guess. His uncle had always spoken of “Texas” with a peculiar softness in his voice, like a man recalling a dream that had felt more real than reality.

He slid the photograph into a box labeled “Keep.”

Stories have a way of settling into the land that holds them.

Out in those quiet Texas fields, when the wind is just right and the wheat—or what little is left of it in a world of subdivisions and paved roads—rustles against itself, there is a sound like an old engine turning over. It’s not much. Just a hum, a vibration, a memory.

Somewhere in that hum is a stubborn tractor that wouldn’t start, a field that nearly went to waste, a barbed wire fence that surrendered a small piece of itself for a different purpose. Somewhere in it is a mechanic from Stuttgart whose clever “stupid” wire trick did more than bridge a gap in an ignition circuit.

It bridged, for a moment, a gap between enemies.

And in that gap, for the space of a harvest and a shared meal, something small but important was repaired—something that had been broken long before the first shot of that war was ever fired.

The tractor ran. The farm survived. A letter crossed an ocean. A photograph hung on two different walls in two different countries. And men who had every reason to distrust each other chose, for one brief moment, to do the opposite.

Peace doesn’t always arrive with treaties and parades and headlines. Sometimes it arrives with the twist of pliers on a length of barbed wire, with a nail ground down against a barn step, with a hand extended across a barn doorway.

Sometimes it begins with a “stupid” wire trick that saves a Texas farm.

THE END

News

CH2 – This Is the Best Food I’ve Ever Had” -German Women POWs Tried American Foodfor The First Time

May 8, 1945 Outside Darmstadt, Germany The war in Europe was over. Officially, it was V-E Day. In London,…

Sister Mocked My “Small Investment” Until Her Company’s Stock Crashed

If there’s one thing I learned growing up Morrison, it’s this: Thanksgiving at my parents’ estate was never about…

CH2 – They Mocked His Canopy-Cracked Cockpit Idea — Until It Stopped Enemy Fogging Tactics Cold

February 1943. The Spitfire clawed its way up through the gray over the English Channel, engine howling, prop biting…

My Grandson Called Me From The Police Station Saying “Coach Webb Beat Me… But They Think I Att…”

In thirty-eight years as an educator, I learned that phone calls after midnight never bring good news. Parents don’t…

IN COURT, MY SON POINTED AT ME AND YELLED, “THIS OLD WOMAN JUST WASTES WHAT SHE NEVER EARNED”

If you had told me that one day my own child would stand up in a courtroom, point at…

How an 11-Second Signal From a Farm Girl Prevented 38,412 Deaths in a Valley Built to Kill

At 05:46 in the morning, under a low ceiling of fog rolling across the French bocage, an entire Allied…

End of content

No more pages to load