On the morning of February 1st, 1944, the world narrowed down to a lump of frozen earth, a too-heavy gun, and the sharp, metallic snap of bullets passing six inches from a young man’s face.

Private First Class Alton Warren Nappenburger lay belly-down on a low rise of ground near Cisterna di Latina, Italy, his chest pressed into the cold soil, his cheek on the worn wood of a Browning Automatic Rifle. Three German MG42 machine guns were tearing his platoon apart from positions somewhere between eighty-five and a hundred-twenty yards away.

He had twenty rounds left in his magazine. Eleven kilograms of steel and wood in his hands. And every German gun within three hundred yards now had one target:

The kid on the little rise.

Doctrine said: Seek cover. Stay low. Don’t expose yourself.

Twenty-year-old Alton Nappenburger did the opposite.

He’d crawled to the highest point in that field and stayed there.

1. The Deer Hunter

To understand how a brick-factory kid from Spring Mount, Pennsylvania, ended up alone on a bare little hill in front of an entire German counterattack, you have to rewind a decade and a half, to a boy with a .30-30 and a borrowed tree stand.

Alton was born December 31st, 1923, the last baby of the year in a town nobody outside Montgomery County had heard of. Spring Mount was rural country: patchwork fields, second-growth woods, and a sky big enough to swallow your worries if you stared at it long enough.

His father worked in a factory. His mother kept the house and kept three kids fed during the hard years. Money was tight enough that every shot had a dollar sign attached to it.

By twelve, Alton had a rifle in his hands more often than not. Hunting wasn’t a hobby. It was a way to put meat on the table and some pride in his old man’s eyes.

His father’s rule was simple: You get one shot. Make it count.

A .30-30 Winchester cartridge cost money. You didn’t blaze away at movement. You waited. You breathed. You read the woods.

That was how he learned about elevation.

Other kids still-hunted, creeping along the deer trails, hoping to stumble into a shot. Alton’s father preferred stands—especially high ones.

“Deer live down there,” his father told him, pointing along a muddy trail carved through the underbrush. “They look out, not up. You get above ‘em, you see the trails, the crossings, the bedding areas. You see everything. They don’t see you.”

The first time Alton climbed into a tree stand, the world changed. It wasn’t just the height. It was the perspective.

From up there, he could see how all the trails connected. Where the does came out at dusk. Where the old buck circled downwind. Where the patch of thick brush acted like a funnel.

Height meant vision. Vision meant control.

He learned to sit six hours without moving more than a finger. He learned to watch, not just look. To notice the flick of an ear, the twitch of a tail, the way the woods went quiet one heartbeat before something stepped out.

Patience became muscle memory. The rhythm was always the same:

Study the ground first. Pick the right stand. Go high. Wait. One shot, one deer.

Later, when he was loading bricks instead of cartridges, he didn’t know those lessons were burrowing deeper than any math problem he’d ever seen.

But they were.

2. Drafted

Before the war, Alton’s world shrank to ten-hour shifts at the brick factory.

Fifty-pound bricks, stacked, carried, loaded. Heat in summer that felt like you were working inside the sun. Cold in winter that made the mortar on your gloves freeze stiff.

The work built his back and his legs. It didn’t change much else.

Then December 7th, 1941, happened, and everything changed.

Pearl Harbor woke up a country that had been half-trying not to look at Europe. The papers filled with pictures of burning ships and lists of the dead. Men lined up at recruiting offices.

Alton didn’t. Not right away.

He was nineteen, and the factory needed bodies. His father’s job came with a draft deferment. His didn’t.

The letter came from the Selective Service in March 1943, a thin envelope with a heavy future.

Report for induction.

He didn’t feel like a hero when he boarded the train for Fort Meade, Maryland. He felt like a brick-handler who’d been told to carry something different.

Basic training taught him a new language: eight-round clips, field-stripping, forced marches. They handed him an M1 Garand first: .30-06 rounds, semi-automatic, eight shots of American industrial confidence.

He learned how to walk low and run fast. How to hit the dirt when someone yelled, “Incoming!” How to clean mud out of a barrel with cold, numb fingers.

The instructors hammered doctrine into them.

Use cover.

Stay low.

Conserve ammunition.

“Your head is not bulletproof,” one sergeant barked. “If I see you standing up on any battlefield, I will personally shoot you myself.”

They laughed. Then they ran more laps.

After a few weeks, a supply sergeant looked at Alton’s height and shoulders and handed him something heavier.

“Congratulations,” he said. “You’re the BAR man now.”

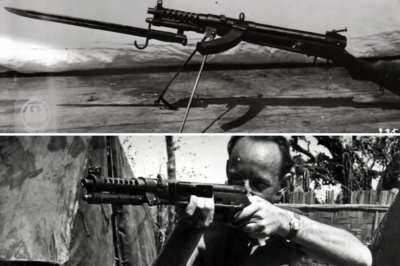

The Browning Automatic Rifle, M1918A2. Eleven kilograms loaded. Twenty-round box magazine. Same .30-06 cartridge as the Garand, but more of it, faster.

Two rates of fire: slow, three to four hundred rounds per minute; fast, five to six hundred. No quick-change barrel. No tripod. No water cooling.

“The BAR is your girlfriend now,” the sergeant told him. “You sleep next to it. You clean it better than your teeth. You drop it, I drop you.”

In doctrine, the BAR was the squad’s light machine gun. It was there to put lead in the air, to make the enemy keep their heads down.

In practice, it meant the heaviest load on the longest marches.

Alton adjusted the sling and thought: It’s just a different kind of rifle. Same job. See first. Shoot first.

They taught him to shoot from a prone position, to hug the dirt and crawl. They taught him fire discipline: short bursts, not wild sprays. They told him to stay in the low ground, to use ditches and walls, to never silhouette himself on a ridge.

He listened. He learned.

But the woods of Pennsylvania hadn’t gone anywhere. Somewhere in the back of his brain, a hunter’s logic quietly disagreed.

3. Italy

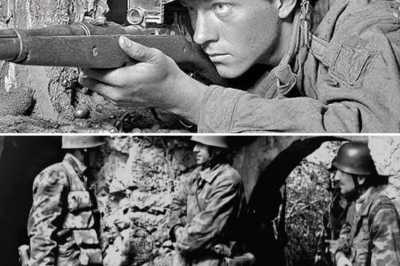

The Third Infantry Division—the “Rock of the Marne”—shipped out to the Mediterranean in late 1943.

Alton brought his BAR aboard the troop ship like a man bringing a familiar tool into an unfamiliar job.

They hit the beaches at Salerno in Operation Avalanche. It was his first real taste of war, and it was nothing like training.

Artillery punches in the air that you felt in your lungs. The crack of German rifles. The MG42’s mechanical scream, a high-pitched tearing sound that didn’t sound like anything that should come out of a human world.

He did his job. He fired when told. He learned how long you could stay in one place before someone started walking mortar rounds toward you.

The campaign blurred: the Volturno River, muddy and cold, crossing under fire. The long slog toward Monte Cassino, where the monastery sat like a watching god on a blasted hill.

He didn’t rack up a kill count. He didn’t win medals or headlines. He carried the BAR and tried not to think about what each trigger squeeze meant to whoever was downrange.

The platoon called him “Nappy.” It was shorter than Nappenburger and easier to shout over gunfire.

He was twenty by the time the division got orders for a new operation: a landing behind German lines at a place called Anzio.

Operation Shingle, January 22nd, 1944.

The idea was simple on paper: land fifty kilometers south of Rome, outflank the Gustav Line, and smash open the road to the capital.

They came ashore to a strange, almost eerie quiet. The Germans were surprised, scattered. For once, Allied troops stepped onto an Italian beach without being immediately shredded.

But the man in charge, General John P. Lucas, hesitated.

Instead of pushing hard for Rome, he dug in.

That gave Field Marshal Albert Kesselring exactly what he needed: time.

Within forty-eight hours, hardened veterans from the Hermann Göring Panzer Division and the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division were streaming in from the north and south, tightening a ring around the shallow Allied beachhead.

By January 30th, the Anzio perimeter was a long, thin oval fifteen kilometers deep and twenty-five wide, backed up against the sea with nowhere to run if it broke.

The Germans intended to break it.

They hit the Rangers first.

4. The Walk to the Null

Darby’s Rangers were supposed to punch through the German lines and seize the town of Cisterna di Latina, a road hub that would have opened a crack in the German ring.

They vanished instead.

Seven hundred sixty-one Rangers were killed or captured in the fields and ditches before Cisterna. A whole hard-fighting force, swallowed in a day.

The Third Division tried to break through to help them and failed. The ground was too flat, the enemy too strong, the machine guns too fast.

By the evening of January 31st, rumors ran through the company like cold water: Germans massing for a major counterattack. The kind that didn’t just push you back a line or two—it shoved you into the sea.

Company C got orders: reconnaissance patrol near Cisterna. Find the German positions before the hammer came down.

Alton packed six magazines for his BAR. One in the gun, five on his belt. Twenty rounds each.

One hundred twenty bullets between him and whatever the next day brought.

The morning of February 1st was gray and cold. Central Italy in winter is a damp chill that gets into your bones and lives there.

The patrol stepped off at 11:30.

Thirty to forty men spread out in a ragged line, moving across low, open farmland.

No hedgerows. No stone walls. Just recently harvested wheat fields, the stubble ten to fifteen centimeters high. The soil was semi-frozen, crusted on top, soft underneath.

The only variation was in the tiny, natural folds of the earth—depressions barely a foot deep, hardly enough to hide a man lying flat.

The orders were simple: advance three hundred meters, locate the Germans, and pull back.

Alton walked on the right flank, BAR at the ready, breath puffing in little clouds.

His hunter’s eyes went to work on instinct.

Too open, he thought. Too quiet.

In the woods back home, a silent patch was either empty or full of eyes.

The men around him scanned ahead, looking for obvious things: trenches, bunkers, helmets. He watched for less obvious ones: a darker patch in the field, a crease where there shouldn’t be one, a flash of glass.

He didn’t see the guns.

He heard them.

At 11:45, the first MG42 opened up.

5. Caught in the Crossfire

If a bolt-action rifle is a hammer, the MG42 is a buzz saw.

The sound ripped across the field—a high, tearing shriek at 1,200 rounds per minute, like someone running a chainsaw through sheet metal.

The first burst cut down three men before anyone knew where to dive.

The rest threw themselves into whatever shallow hollows they could find, trying to melt into ten inches of earth.

A second MG42 answered from the left, then a third from the right.

In less than fifteen seconds, the patrol was in a textbook crossfire: three machine guns on a shallow arc, overlapping lines of fire, no cover worthy of the name.

The lieutenant shouted something about flanking, about smoke. Nobody could move.

Every time someone lifted their head above the stubble, the nearest gun walked a line of bullets right at them.

Alton hugged a shallow depression, BAR pointed forward, heart pounding.

He couldn’t see the nests directly, but he could read the field.

The first MG42—ahead, maybe eighty-five yards. Muzzle flashes flickered low over a slight dip in the earth. Smoke puffed where the barrel met the air.

The second—off to the left, about a hundred yards. He caught glimpses of the belt-feeder’s hands, the glint of steel as the barrel shifted.

The third—right, farther out, maybe a hundred-twenty yards. That one was better camouflaged. All he had was the sound: sharper, a little delayed.

Three guns. Three crews. At least six to nine men. Probably more infantry scattered around.

The Americans had a handful of rifles, one BAR, a few grenades, and dirt that barely covered their elbows.

Fifteen minutes passed like that.

Bullets snapped overhead, smacking into the ground, kicking up tiny geysers of dirt. Men tried to shift positions by inches. Each time, the MGs stitched lines close enough to brush boots and helmets.

Alton pressed his face into the cold soil, breathing in the smell of dirt and cordite.

He thought about the woods.

Back home, if you walked into an open field with deer bedded on the far side and no cover between, you didn’t try to crawl through the grass and hope they didn’t see you.

You found a different angle. A different height.

He looked ahead.

Sixty yards in front of him, the field swelled into a small rise—a low knoll, maybe two or three meters higher than the surrounding ground. To everyone else, it was just another bump in a bad landscape.

To a hunter, it was a stand.

From up there, he realized, he’d be able to see over the little folds of earth, to pick out the guns that were only flashes and noise from down here.

He’d also be the highest thing in a very flat field.

They’ll see you, the survival instinct whispered.

They’ll shoot at you, another part of his brain answered.

But if they’re shooting at me, he thought, they’re not shooting at the rest of the boys.

He turned his head toward the nearest American, huddled in a depression to his left.

“I’m going to that knoll,” he said.

The soldier stared at him like he’d announced he was going to sprout wings and fly away.

“You’re insane,” the man hissed. “You’ll be dead in ten seconds, Nappy.”

“They can’t kill all of us if they’re shooting at me,” Alton said.

He didn’t say it dramatically. He said it the way you’d say, The trail’s going to cross by that oak. Simple fact.

Far behind them, the lieutenant couldn’t see him. No one had ordered this. No manual suggested climbing the only obvious piece of ground in front of three enemy machine guns.

Doctrine said: Stay low.

The hunter in him said: Go high. See more. Control the field.

He slid the BAR forward and started to crawl.

6. The Crawl

It was sixty yards from his shallow scrape to the base of the knoll.

Sixty yards in an open field with three MG42s tearing up the world around him.

He kept the BAR tucked tight with his right hand, dragging it along next to his body. His elbows and knees pulled him forward in jerky, inching motions. The semi-frozen earth scraped skin through his fatigues.

Ten yards ahead, a dead American lay facedown in the stubble, arms sprawled.

Alton crawled past him.

He’d look later, if he lived, see who it had been.

An MG42 swept the area, bullets walking two meters to his left, stitching a line of dirt fountains toward the lieutenant’s position.

He froze, pressing himself into the cold ground, every muscle screaming to keep still.

Ten seconds.

The gun fell silent—barrel change or belt reload.

He moved again.

Thirty yards.

Forty.

Fifty.

He stayed low, using the tiny undulations of the terrain to mask his approach. The Germans focused on the main American line. Big movements, bigger targets.

At fifty yards, he reached the base of the knoll. The ground began to slope upward.

The next few yards would take him above the level of the field.

If they saw him now, he’d be a man on a range silhouette.

He went anyway.

He crawled the last meters, heart pounding, every inch a dare.

Then he was on top.

7. The Stand

He flattened himself out again, BAR forward, and let his eyes adjust to the new angle.

The field opened up around him.

Behind, sprawled across a hundred-fifty meters of front, thirty Americans were pinned wherever they’d managed to fall. Some moved. Some didn’t.

Ahead, he saw what had been hidden from ground level.

MG nest number one: eighty-five yards straight ahead. Three men in a shallow pit behind low sandbags, the MG42 on a tripod. The gunner hunched behind the sights, the assistant feeding the belt, the third man spotting.

MG nest number two: a hundred yards to the left. Two men visible, one firing, one feeding. Their position was a little sloppier, bags piled low, barrel rock-steady.

MG nest number three: a hundred-twenty yards to the right. More cleverly dug-in. All he could see was the stuttering, dark line of the barrel and the occasional glint of a helmet as the crew shifted.

He had 20 rounds left in his current magazine and five more on his belt.

He switched the BAR’s rate selector to slow—three to four hundred rounds per minute. He’d grown up counting cartridges. He wasn’t about to hose away his entire load in two seconds.

Closest threat first.

He settled into the stock, cheek against the gouged wood, sights aligned on the gunner in nest one.

Breath in.

Hold.

Squeeze.

The BAR thumped four times in a quick, controlled cough.

The gunner jerked backward, dropped out of sight.

The assistant froze, his hands still on the belt. Shock is universal. For a second, he looked around, trying to understand why the man behind the gun had disappeared.

Alton fired three more shots.

The assistant toppled sideways across the MG’s receiver.

The third man in the pit reacted the way a lot of men do when hell lands in their laps. He ran.

Nest one went silent.

For an instant, across the field, there was a jagged little hole in the curtain of fire.

The men in nests two and three noticed.

It took them about five seconds to figure out where the killing had come from.

Then both MG42s swung toward the knoll.

8. Human Bait

The world around him detonated into moving air and sharp, invisible lines of death.

The unique sound of supersonic rounds zipped and cracked overhead. Bullets tore into the top of the knoll, throwing up spouts of dirt. One snapped past his ear close enough that he could feel the hot rush of its wake.

Another snapped through his sleeve, jerking the fabric, leaving a neat, ragged hole and unmarked skin.

A third slammed into the BAR’s wooden stock, gouging out a long, splintered groove where his cheek had rested seconds earlier.

Instinct, training, and a decade of deer hunting all agreed on one thing: don’t stay in one place.

In the woods, deer go on alert when something big and still appears where nothing was before. Hunters know to shift just a little, to break up the pattern.

On a battlefield, German gunners aim where they last saw you.

Alton rolled two meters to his right, hugging the knoll’s curve. It wasn’t much, but it was enough. Bullets chewed the spot he’d just vacated.

They wanted him. Every gun in the area was swiveling toward the idiot kid who’d climbed the only bump in the field.

Good, he thought, in the narrow, focused way that shows up when you’ve decided you’ve probably already spent your life.

If they’re shooting at me, they’re not shooting at the boys behind me.

He kept moving, a meter at a time, every few seconds. Never predictable, never settling, making the Germans adjust and re-acquire.

That was the “human bait trick” in its rawest form.

It wasn’t complicated. It was just ugly.

Make yourself the juiciest target around, and you control where the enemy looks.

From the American line behind him, men glanced up, stunned, when they realized the thunder centered on the knoll. For the first time in nearly half an hour, some of them could raise their heads more than an inch without getting them shot off.

One of them shouted something unprintable about Nappy losing his mind.

Then they started to understand what he was doing.

9. The Grenadiers

At 12:12, Alton spotted movement to his left.

Two German grenadiers were advancing from that side, moving in textbook tactical bounds. Five to ten meters at a crouched run, then drop. Then the other man would sprint past him.

They were Panzergrenadiers, infantry trained to fight alongside armor. He could tell by the kit and the way they moved.

Each had three or four Stielhandgranaten—stick grenades—tucked through their belts. Pistols at their hips, rifles slung.

They were coming for the knoll.

That was smart. You don’t leave an outpost of American courage sticking out like that if you have any say in it. You close in. You lob explosives. You finish it.

Distance: forty yards.

Thirty.

Twenty-five.

From that elevation, Alton could see them clearly. They could see him too if they looked.

He didn’t fire yet.

In the woods, you didn’t take a shot at a deer the second it came into view. You waited for the right moment. Too early, and you scared the animal and blew the chance. Too late, and it stepped behind a tree.

He let them come.

At twenty yards, they were committed. Too far to throw accurately yet, too close to back out.

He thumbed the selector to slow. He wanted control.

He put the front sight on the lead man’s chest.

Squeeze.

The BAR spat six quick rounds.

The first grenadier folded, momentum carrying him forward as he crashed into the dirt.

The second ripped a grenade from his belt, arm cocking back in a practiced motion.

Alton shifted a fraction, pressed the trigger again. Four rounds.

The second man jerked as if punched, the grenade leaving his hand in a weak arc. It sailed wide and detonated fifteen meters away, the explosion kicking up a shower of dirt and debris that pattered against the knoll.

Two more men down.

Two more sets of eyes off the field.

The MG42s punished him for that, their tracers carving dirty orange lines around his position.

He rolled again. Kept moving. Kept breathing.

10. Silencing Nest Two

MG nest number two was still spitting death.

It sat a hundred yards left, a little farther than the first, low in the ground, sandbags just high enough to conceal most of the crew.

At that range, with that kind of position, he wasn’t looking to put every bullet into a man’s chest. He needed to make them duck.

He flicked the BAR to fast—five to six hundred rounds per minute.

He touched the trigger for a burst, riding the recoil, walking the tracers into the pit.

Ten rounds flew in a second and a half, five of them incendiary tracers that etched bright streaks through the air.

The MG42 shut up for a moment. Instinct, again: when bullets start chewing the sandbags in front of you, you tend to get your head down.

He hit them again. Eight rounds this time. He saw one man flinch, then slump backward, his body falling against the gun.

The second man tried to pull the MG back into action, hands on the grips, teeth bared.

Alton sent six more rounds into the nest.

The second man disappeared.

Nest two went quiet.

The field behind the knoll shifted almost physically. Where three cutting lines had scythed, now only one was left.

So far, he’d burned through somewhere between fifty and seventy rounds. His barrel was hot enough to brand cattle. The BAR wasn’t built for sustained machine-gun work. It was a glorified automatic rifle that some ordnance officer had decided could fill a light machine gun role.

Overheat it, and it could seize or fire uncontrollably.

He eased off the rate, thumbed the selector back to slow.

He popped the magazine, weighed it in his hand, gauging the emptiness by feel.

Three rounds left.

He slapped it back in.

Nest three was still up, at a hundred-twenty yards, and whoever was running it was angry.

Bullets hammered the knoll. One hit six inches from his head, blowing a divot in the dirt and showering his face with soil.

Another struck the BAR’s stock again, deepening the gouge where his cheek had nestled an hour ago.

Another ripped his sleeve open from wrist to elbow, flapping fabric.

Skin intact. Luck, angle, God, whatever you wanted to call it.

He moved again. A meter to the left this time. Then back. Never a pattern.

He knew he couldn’t do this forever.

Then the infantry came.

11. The Assault Platoon

Around 12:30, he saw them: gray-green figures emerging over a slight fold in the field to his rear right.

Twenty to thirty German soldiers, spaced, moving in a disciplined staggered line.

An assault platoon.

They were coming not from directly ahead, but from behind his original line—circling, trying to hit the knoll from an angle the BAR couldn’t easily cover and then roll up the American platoon from the side.

Initial distance: about a hundred-fifty yards.

He made a decision.

MG nest three was too far, too well-dug-in for precise work with his remaining rounds. The infantry were a closer, far more immediate threat.

He turned his body, pivoting the BAR to face the advancing line.

Selector: fast.

At a hundred yards, he started firing.

Four-round bursts, each about half a second, then shift aim.

The first man in the line jerked and went down, rifle spinning away.

The second caught a round in the leg, collapsing with a scream that cut across the field even through the gunfire.

Third. Fourth. Fifth.

In thirty seconds, five or six of the advancing Germans lay still or writhing.

The rest scattered, dropping into whatever depressions they could find, vanished in the stubble and folds.

Alton didn’t stop. Every time he saw a helmet lift, a shoulder shift, he stitched a short burst at it.

One man tried to crawl forward, hugging the ground. A few yards. Another. Head up for a quick look.

Three rounds. He lay flat and didn’t move again.

Another shifted too close to a dead comrade, using the body as cover. That worked right up until a tracer found him.

Fire from the knoll pinned the assault as thoroughly as machine-gun fire had pinned the Americans earlier.

From somewhere in the German line came harsh shouting, commands, curses.

After a minute of that one-sided exchange, the survivors began to withdraw, belly-crawling backward, then getting up to scamper out of range when they thought they were far enough.

Ten to twelve more Germans out of the fight. Some forever, some for long enough that they wouldn’t be a problem in the next half hour.

The human bait trick had teeth.

Alton’s magazine did not.

He squeezed the trigger and heard the worst sound in combat short of a click when you expect a boom:

Click.

Empty.

12. The Gamble

He rolled back into a little fold at the top of the knoll and slapped a fresh magazine home.

It was his last full one.

Twenty rounds.

The MG42 in nest three was still spraying the area, cutting the top of the knoll to ribbons. Each burst sounded a little more strained, a little more panicked.

He risked a quick look. At that distance, he still couldn’t see much. Just the dark mouth of the barrel and the shimmer of heat in front of it.

His ammo situation was simple math now.

Last mag, plus whatever he could scrounge.

He thought about the dead American at the bottom of the knoll.

He’d seen the man’s cartridge belt on the way up. M1 Garand clips. Same .30-06 cartridges. Different format.

Garand: eight-round en-bloc clips that fed straight into the rifle.

BAR: twenty-round detachable box magazines.

You couldn’t jam a clip into a BAR. But you could strip the rounds out and push them into a magazine, one by one.

Under fire.

In an open field.

He had a choice: stay up here and run dry in the next engagement, or crawl back down into the gun-swept field and try to steal bullets off a corpse.

Certain risk now versus certain death later.

He made the same choice he’d made when he crawled off the line toward the knoll.

Move.

At about 12:43, he started down.

13. Reloading Under Fire

He slid backward off the crest, keeping his body as low as possible, BAR clutched tight.

The moment he left the relative shelter of the knoll’s crown, the MG42 spotted movement and pounced.

Bursts chewed up the slope around him, dirt spattering his helmet and neck.

He kept going, counting the yards in his head.

Five.

Ten.

Fifteen.

The German gunner walked his fire where he thought Alton would be. Alton wriggled slightly to the side, always trying to stay one step ahead of someone he couldn’t see.

A grenade detonated five meters away, a sharp, concussive thump that rattled his bones and filled his mouth with the taste of dust and metal.

He didn’t stop.

He reached the body of the dead American he’d passed earlier.

The man lay on his back now, moved slightly by the blasts or the shifting earth. His eyes were half-open, staring at a sky that had nothing to offer.

Alton didn’t let himself think much about it.

He stripped the man’s cartridge belt off with fumbling fingers. Six Garand clips. Eight rounds each. Forty-eight cartridges.

No BAR magazines. The man had carried an M1.

He fumbled an empty BAR magazine out of his pouch and pressed the first clip against his palm, pushing the cartridges out into his hand.

The shells felt colder than the ground, smooth brass in his shaking fingers.

One by one, he thumbed them into the BAR mag.

One.

Two.

Three.

Four.

He flinched as an MG42 burst went by overhead, a whipcrack line of sound.

Five.

Six.

Seven.

Eight.

He grabbed a second clip, stripped it. Cartridges dropped into the magazine, his fingers slipping a little on the metal.

Nine.

Ten.

Eleven.

Twelve.

His hands were shaking too much now to move at full speed. He wanted twenty in there. He doubted he’d get twenty in there.

Thirteen.

Fourteen.

Fifteen.

Sixteen.

Another burst. Closer. Dirt peppered the side of his face.

“Good enough,” he muttered.

He shoved the half-full magazine into place. He stuffed the remaining clips—about thirty-two loose rounds—into his pockets.

Then he crawled back up.

Bullets chased him. Grenade fragments harried him. He moved anyway.

At 12:46, he was back on the crest.

14. Two Hours on the Knoll

The next hour was a blur composed of patterns.

The Germans tried again, from left, right, center.

Small groups, probing, hoping to catch the BAR reloading or the man behind it flinching.

Each time, Alton answered.

He’d pop up just enough to see, fire controlled bursts, then shift position and vanish again behind the little curves of the knoll.

He developed a rhythm.

Fire.

Move two meters.

Reload.

Fire.

Move.

Reload.

Each reload now involved feeding loose cartridges from clips into magazines by hand. Two to three minutes, if he hurried, each minute an eternity when you’re the center of attention for every gun within three hundred yards.

He’d strip rounds, push them into the mag until his hands slipped or the shells wouldn’t seat smoothly anymore, then slam the magazine home and get back to the business of making sure nobody got close enough to lob a grenade into his face.

The BAR’s barrel grew so hot you could have fried an egg on it. Heat shimmered in the air around the muzzle. He knew the danger of cook-off—rounds firing from residual heat without a trigger pull—but there wasn’t much to be done about it. He couldn’t swap barrels the way a German crew could with an MG42.

All he could do was control his bursts, give the gun seconds to breathe between strings.

Around 13:20, somewhere in that long, ragged stretch, MG nest three finally went silent.

Whether his rounds had finally found a gap in their cover, or a mortar round from further back had hit, or the crew had simply decided they’d had enough and crawled away, he never found out.

He only knew the sudden absence of that particular tearing sound made the field feel different.

They weren’t done yet. Snipers took potshots. Rifles cracked. A stray machine gun from farther back sent experimental lines of tracers his way now and then.

But the worst of the crossfire was gone.

Behind him, for the first time in two hours, American soldiers could move.

They crawled. They slid. Some stood and ran low to new positions. Stretchers appeared, medics grabbing the wounded and dragging them back toward the relative safety of the beachhead.

No one advanced very far. They didn’t have to. The mission now wasn’t to charge the German lines and take ground.

The mission was survival.

And that depended, to a surprising degree, on one young man refusing to get off a little hump of dirt.

15. Walking Off the Hill

At 14:00 hours—two and a half hours after the first MG42 had opened up—the immediate danger in that particular slice of Italy eased.

The German infantry had pulled back to regroup. Their immediate attempt to roll up that sector of the line had failed.

The platoon’s officer cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted toward the knoll.

“Nappy! Get down here!”

Alton fired his last rounds in a short, bitter burst toward a distant flash of movement. Then he got to his knees and finally, carefully, stood.

His legs nearly shook out from under him. His arms felt like someone else’s.

He slung the BAR, barrel still warm enough to hurt, stock scarred with a long, ugly groove where the bullet had chewed into it.

He walked back toward the American lines.

It wasn’t a triumphant march. He wasn’t thinking about victory. He was thinking about not falling on his face.

Men stared at him as he came off that knoll.

His uniform had three fresh bullet holes—through the sleeve, through the jacket, near the hem. The fabric flapped in the cold breeze. No blood.

The BAR’s stock was splintered where a 7.92mm round had chosen wood over bone.

His face was streaked with dirt and sweat and powder. His eyes looked like someone had wiped them clean of everything but exhaustion.

“You held ‘em for two hours alone,” somebody said quietly.

He didn’t answer. His mouth was too dry, his brain too empty.

A medic grabbed his arm and ran practiced hands over his torso, searching for unseen wounds. Nothing. Not a scratch.

Call it luck. Call it Providence. Call it physics and angles.

Whatever it was, it had left him intact.

Behind him, bodies lay in arcs that told their own story.

16. Counting the Dead

A few days later, when the front in that sector had shifted and the immediate pressure relented, intelligence officers and staff NCOs walked the field around the knoll.

They were looking for hard numbers to match the stories that had already started circulating.

From the crest of the knoll outward, in a rough 180-degree arc, they counted German bodies.

Near the remains of MG nest one, three dead men. Nest two, two to four more, depending on how you estimated the blood trails leading away. Two grenadiers below the left flank of the knoll.

In the areas where the assault platoons had tried to advance, ten to twelve bodies, plus signs of wounded being dragged off—bloody bandages, dropped equipment, churned soil.

Around other approach routes, more. Soldiers killed in ones and twos, hidden in little dips, sprawled where they’d thought they were safe.

In total, somewhere around sixty German casualties—dead and seriously wounded—could be traced to that two-hour window and that one BAR on that one knoll.

Numbers in war are slippery. Some reports rounded it to fifty-two. Others said “at least sixty.” In the end, the exact figure mattered less than the effect.

A German counterattack that should have smashed a company and rolled a section of the beachhead into the sea had instead broken against a bump in the earth and a twenty-year-old who refused to lie down.

The division’s commanding general, Lucian Truscott, heard about it.

He called Alton a “one-man army.”

Headquarters recommended the Medal of Honor.

17. After the Hill

The war didn’t end for Alton just because someone pinned a ribbon on a piece of paper with his name on it.

From February through May 1944, the Third Infantry Division kept fighting out of the Anzio pocket.

Artillery barrages. Counterattacks. Mud. Blood. Another day, another field, another set of orders nobody below the rank of colonel really understood.

On May 23rd, the Allies launched Operation Diadem, the breakout from Anzio.

This time, they pushed.

The German lines buckled. They didn’t break cleanly, but they gave way enough for the American and British divisions to finally move inland.

On June 4th, they marched into Rome.

Locals leaned out of windows, threw flowers, shouted “Americani!” Priests crossed themselves as the long columns of tanks and trucks rolled in.

Somewhere in that line was a quiet kid from Spring Mount who’d learned long ago that being higher than your target gave you an edge.

He didn’t wave much. He didn’t grin for the cameras.

He just kept walking, hands on the worn strap of a BAR that had already seen more war than many men.

On May 26th, 1944, the Army paused the shooting long enough to hold a ceremony.

The Medal of Honor is the highest award for valor the United States can give. They don’t hand it out like candy. When they do, it’s usually in a formal setting, with generals and flags and a reading that sounds like Scripture written in the language of war.

They read Alton’s citation aloud.

They talked about how he had “moved to an exposed knoll and from this position engaged the enemy machine guns, killing the crew of one and forcing the others to cease fire.” They mentioned bullets striking within six inches of his body, hitting his clothing and rifle. They described how he crawled fifteen yards under heavy fire to retrieve rifle clips from a fallen comrade and reloaded his BAR by hand, then returned to the crest to continue firing.

They said he had “singlehandedly broken up a determined enemy attack” and that his “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life” had reflected the highest credit on him and the armed forces.

He stood there, twenty years old, with five months of combat behind him, while a general pinned a five-pointed star on his chest.

Flashbulbs popped. Hands were shaken. Someone told him to look at the camera.

Later, they sent him back to the United States.

18. Human Bait on Tour

War doesn’t just run on bullets and gasoline. It runs on money, too.

War bond tours were the home-front side of the fight. You took a young man who’d done something nobody could quite believe, cleaned him up, put him in a uniform that didn’t smell like fear and mud, and sent him around the country to stand on stages in front of crowds.

He’d tell his story. Or a version of it. People would buy bonds. Factories would get funded. Ships would be built. The war machine would keep turning.

Alton did his duty there, too.

He stood under hot lights in school auditoriums and on courthouse steps, with the Medal of Honor star on his chest, and tried to explain how a brick-factory kid had ended up on that knoll.

He talked about his buddies.

He talked about the German machine guns.

He sometimes left out the part about spilling his own fear into the dirt through his pores.

He didn’t brag. He didn’t romanticize it. He didn’t have to. The facts were dramatic enough on their own.

Whenever a reporter asked him what had possessed him to crawl toward the highest, most exposed point on the battlefield when every instinct says to dig deeper, he’d shrug.

“Somebody had to do something,” he’d say. “They were getting chewed up. From up there I could see ‘em better. They could see me better too. But if they were shooting at me, they weren’t shooting at my brothers.”

The phrase “human bait trick” came later, wrapped around the story by others. He never used those words. Not then.

He just told it the way it had felt: a series of practical decisions made in a place where staying still equaled death.

When the tour ended, and the war started winding down, the Army had to decide what to do with men like him.

Some stayed in, made a career of it.

He went home.

19. Doctrine and the Null

The Army didn’t rewrite its field manuals because one private had broken the rules and survived.

The books still said:

Use cover.

Stay low.

Don’t expose yourself unnecessarily.

Those things stay true in most fights.

But Alton’s story got told at the Infantry School at Fort Benning.

It became a case study, not in recklessness, but in adaptation.

Terrain plus situation overrides doctrine.

On a flat field with shallow depressions and enemy guns in low positions, the highest exposed point had become, paradoxically, the best place from which to control the fight.

From that elevation, a single man with a BAR and the willingness to be a target had controlled the geometry of the battlefield.

Exposure equaled visibility.

Visibility equaled control.

Control changed the outcome.

Instructors used his story as an example of initiative when command is paralyzed. When the lieutenant can’t see, when the sergeant’s pinned, the private with a view has to think for himself.

They emphasized that you don’t go looking for knolls to die on in every fight.

But they also emphasized that sometimes, the “unsafe” move, made at the right time for the right reasons, is the only one that makes everyone else safe.

20. Back to Pennsylvania

After the headlines faded and the war tapered off into occupied zones and treaties, Alton went back to something like normal life.

He returned to Pennsylvania. The factory and the fields were still there. Spring Mount still smelled like damp earth and exhaust and someone somewhere burning leaves.

He got work as a truck driver. Later, he became a supervisor on an asphalt paving crew. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was honest, solid, needed.

He married. Had kids. Later, grandkids.

He didn’t hang the Medal of Honor in the front hall. He didn’t introduce himself as a hero.

Local veterans knew. Word gets around. But he wasn’t the type to hold court at the VFW, regaling everyone with the same story every Friday night.

If someone asked directly, he’d answer. If they didn’t, he let the subject rest.

He took his kids and then his grandkids into the woods when deer season came around.

He showed them how to read a trail, how to pick a stand, how to sit still when your legs itched and your nose wanted to sneeze.

“Up there,” he’d say, pointing to a good tree, “you can see everything. They don’t think to look up.”

He didn’t always add: Sometimes that works the other way around, too. Sometimes being where they’re looking is how you save the ones they’re not.

He passed on a civilian version of the skill that had saved him and thirty men on a February day in Italy.

Quiet. Simple. Practical.

21. The End of the Trail

On June 9th, 2008, at eighty-four years old, Alton Warren Nappenburger died.

He’d lived long enough to see his kids grow up, his grandkids born, a world that had been rip-torn by war put itself back together in new, complicated ways.

The Army buried him with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

The headstone is simple.

Name.

Rank: Private First Class.

Decoration: Medal of Honor.

No mention of the number of Germans he killed. No mention of the two hours on the knoll. No mention that, for a brief, brutal stretch on February 1st, 1944, a twenty-year-old deer hunter from Spring Mount, Pennsylvania, had been the most important piece of terrain in a ten-square-kilometer patch of Italy.

Somewhere near Cisterna di Latina, that field still exists.

Maybe the knoll has been plowed flatter by decades of farming. Maybe it’s still there, a modest bump in a landscape of wheat and memory.

If you stood on it on a cold morning and looked out across the distance, you might see nothing but stubble and sky.

If you knew where to look, though—if you’d read the reports, heard the stories—you might be able to picture it layered over with another morning:

Three MG42s, stuttering fire from dug-in positions.

Thirty American soldiers pinned in shallow depressions, afraid to move.

A kid from Pennsylvania deciding that if nobody else could see, he’d climb to where he could.

He climbed the knoll the way he’d once climbed into a tree stand.

He lay down.

He waited.

He shot.

He survived.

And he turned himself into human bait so his brothers in arms could live long enough to go home.

Doctrine said: Seek cover.

On that day, on that field, Alton Warren Nappenburger said, in action if not words:

Go high. See more. Control the field.

The cost was his safety.

The payoff was thirty men walking away from a place they should have died.

The stories that filtered back to America said he’d killed fifty-two Germans that day. The numbers on the ground, later, suggested closer to sixty.

He never corrected anybody.

Numbers were for the historians.

For him, the only math that mattered was simple:

More of them got to go home because he didn’t come down from that knoll.

That was enough.

THE END

News

CH2 – American Engineers Test Captured Japanese Type 100 Submachine Gun — Then Realized Why It Failed

March 1944 Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland The crate looked like every other crate that passed through the ordnance receiving…

CH2 – Sniper’s “Stupid” Mirror Trick — The Secret That Tripled His Speed

Metz, France November 3, 1944 — 6:47 a.m. The bakery had died before dawn. Its front wall was half…

CH2 – Sniper’s “Stupid” Mirror Trick — The Secret That Tripled His Speed

February 14, 1943 0347 hours North Atlantic, 600 miles east of Newfoundland The SS Robert Perry broke in half in…

CH2 – How One Metallurgist’s “FORBIDDEN” Alloy Made Iowa Battleship Armor Stop 2,700-Pound AP Shells

November 14th, 1942 Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pennsylvania The projectile hung in the cold air like an accusation. A 2,700-pound steel…

CH2 – How One Farmhand’s “STUPID” Rope Trick Destroyed 35 Zeros in Just 3 Weeks

By dawn on May 7th, 1943, Henderson Field smelled like every airfield in the Southwest Pacific: burned fuel, hot aluminum,…

MY OLDER BROTHER ARRESTED ME ON CHRISTMAS EVE IN FRONT OF MY ENTIRE FAMILY. I THOUGHT MY LIFE WAS…

I can still smell that night. Roasted meat. Cinnamon cookies. Pine from the Christmas tree. The house was so…

End of content

No more pages to load