They called it the Black Pit.

Sailors said the words with a shrug and a joke because that’s what you do when you’re scared. You laugh. You toss a cigarette butt into the wind and pretend your palms aren’t sweating inside your gloves.

But everyone in the North Atlantic in 1943 knew what it really meant.

The Black Pit was the stretch of ocean out beyond the reach of land-based aircraft, beyond the comfort of radar coverage, beyond help. No patrol bombers from Iceland, no Hudsons from Newfoundland, no blips on a screen in some warm operations room. Just gray water, gray sky, and whatever hunted in between.

Out there, ships simply vanished.

1. Convoy in the Dark

September 1943. Somewhere west of Ireland, deep in the Pit.

Forty merchant ships struggled westward through sleet and breaking seas—grain, ammunition, oil, steel, and everything else a nation at war needed. Tankers labored along, decks sheened with freezing spray. Liberty ships and British tramps plowed the swells, their bows rising and slamming down like they were trying to punch through the ocean itself.

On the escort screen, an aging destroyer pitched and rolled, her decks slick, her crew hollow-eyed from too many watches on too little sleep.

In the darkened sonar shack below decks, a young rating named Parker sat with headphones clamped to his ears, face half-lit by the ghostly glow of dials.

He listened to the sea.

Most of the time, the ocean sounded like static—distant hiss, the rush of water against hulls, the occasional ping of his own ship’s active sonar.

That night, for a long time, it was just that. Hiss and nothing.

Then the world exploded.

The first ship took the hit two columns over. Parker heard the muffled thump through the hull half a second before the deck seemed to shudder under his chair.

He tore the headphones off and staggered to the hatchway as alarms began to howl. Out on the starboard wing of the bridge, the night was suddenly orange and white—a column of fire and steam towering up from where a merchantman had been.

“Jesus,” someone breathed beside him.

The ship’s sirens shrieked. The destroyer heeled hard over, racing for the contact they didn’t have.

Out in the convoy, chaos erupted. Ships veered, some slowing, some speeding up, fouling their stations. Signal lamps blinked frantically. The escort captain shouted orders down voice tubes, voice steady only because it had to be.

Another explosion tore the dark open. Then another.

Parker scrambled back to his set as the sonar chief barked in his ear, “Find them!”

He pinged. The active sonar sent out a sharp note that went singing into the deep.

Nothing came back.

Depth charges rolled off the stern anyway, hissing and thumping into the sea. They blossomed below in soundless blooms of water and pressure.

No bodies surfaced. No oil slick marked a kill. Just darkness and cold.

On the bridge, the captain gripped the railing so hard his fingers ached.

The reports that eventually reached the Admiralty in London sounded dry on paper.

CONVOY ONS-18: 11 SHIPS SUNK IN SINGLE ATTACK

HEAVY LOSSES OF BULK CARGO AND OIL

ESCORT UNABLE TO LOCATE OR DESTROY ENEMY SUBMARINES

The paper didn’t carry the screams over the radio, the sudden emptiness on the horizon where ships had been.

Another convoy followed, and another. The numbers turned into obituary lines.

Something new was out there.

Something no one could see or hear coming until it was too late.

2. The Homing Death

The engineers called it the G7es “Zaunkönig,” the wren.

The sailors called it the homing death.

Before the new torpedo, U-boats had fired either straight-running weapons or those that homed on magnetic fields. Those you could dodge, sometimes. They ran a set pattern. They reacted to the iron in a keel.

This one listened.

Inside its fat cigar of a body, a simple but vicious mind spun to life once it was in the water. Twin microphones, one on each side, fed a tiny guidance system. It searched not for metal or wakes, but for sound.

Propeller screws.

Destroyers, with their big engines and fast-turning blades, were shiniest in that invisible world. The very ships meant to protect convoys now drew the torpedoes like magnets.

You didn’t see them coming.

You heard them. Sometimes.

Men on listening sets reported a faint hum in the water, a rising whine that climbed in pitch like a kettle coming to boil. Then nothing but white noise as the torpedo turned tighter and tighter and the escort tried to run.

Sometimes they outran it. More often they didn’t.

Within weeks of the Zaunkönig’s first attacks, Allied shipping losses doubled. Destroyer captains ordered silence at sea—no unnecessary engine noise, no music on the mess deck, no idle banging.

The torpedoes still found them.

In the mess hall of an escort base, a veteran summed it up for a new officer.

“You never saw them,” he said, turning his mug between reddened fingers. “You just heard that little hum and then—” he made a fist opening. “Hell.”

Across the Atlantic, in rooms full of maps and coffee and cigarette haze, planners felt the bottom drop out of their calculations.

The Atlantic lifeline wasn’t a slogan. It was reality. Without convoys, Britain would starve. Without fuel, planes wouldn’t fly, tanks wouldn’t move, factories would go quiet.

Hitler’s U-boats had already made the northern sea one of the war’s bloodiest battlegrounds. Now, with their new acoustic teeth, they threatened to snap the rope entirely.

Admirals demanded answers.

Scientists, pulled into the fight, stared at the data and felt very small.

Out of that desperation, in a cold hut on England’s southern coast, a quiet young physicist began to ask an impolite question:

What if, instead of making the torpedoes deaf, we made them hear the wrong thing?

3. The Woman Who Built Ghosts

On the Dorset coast, the wind knifed in off the Channel and slapped at the blackout curtains of a cluster of wooden huts surrounded by barbed wire.

The sign said something bland: TELECOMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH ESTABLISHMENT. It might as well have said DO NOT ASK QUESTIONS.

Inside, the place hummed.

Generators throbbing in concrete sheds. Typewriters clacking. Oscilloscopes buzzing faintly. The smell of hot solder, boiled tea, and damp wool.

Young men in rumpled uniforms and civilian sweaters argued over equations and circuit diagrams. Mathematicians scribbled on blackboards until their cuffs were chalk-gray. Engineers in rolled sleeves wrestled radars the size of refrigerators into submission.

Most of them were loud. Most of them had been the brightest kid in their school and carried that confidence like another badge.

Joan Curran moved quietly among them.

She was twenty-seven, Welsh-born, Cambridge-trained. Short dark hair, clear eyes, a practical way of moving that wasted no motion. There was nothing particularly dramatic about her at first glance. She looked like she should be in a library, not a war.

Cambridge hadn’t even given her a proper degree when she studied there. Women, in those days, could do the work, sit the exams, outperform most of the men—and receive only a note of thanks. The parchment came years later, backdated like an apology.

The war didn’t care about parchments.

What the Telecommunications Research Establishment cared about was results.

Radar had been one of those results. Not just the radar itself—those rotating dishes on towers and ships—but the tricks built around it.

Three years earlier, Curran had helped invent one of the biggest: strips of aluminum foil, cut to specific lengths. Drop enough of them from a bomber and German radar saw a whole air raid where there was none, or lost real planes in a blizzard of echoes.

They called it “Window.” On the ground, it looked like confetti. In the air, to an operator staring at a green screen in an underground bunker, it looked like ghosts.

Curran knew how to make enemies miss what mattered.

Now there was a new riddle on her workbench.

4. The Torpedo That Thought

They brought her the problem in pieces.

Admiralty officers came down from London, their uniforms neat and their faces pinched from long nights.

They didn’t tell her everything. Clearance levels and old habits and the simple fact that some of them weren’t sure what to make of a woman in a lab coat surrounded by wires and oscillators.

But they told her enough.

New German torpedo. Acoustic homing. Designation G7es. Frequency range 24 to 30 kilohertz—that humming band where Allied propellers sang their song. Twin hydrophones in the nose. Simple filter to ignore random noise, focus on a steady mechanical beat.

“Once it’s in the water, it listens,” one engineer said, voice flat. “And once it hears a destroyer, that’s that.”

Curran listened more than she talked.

She asked for test records. For copies of every sonar trace a convoy had managed to capture before being cut off. For fragments of torpedoes fished up from the sea floor. For every scrap of documentation the Admiralty’s own scientists had generated trying to fight this thing.

They gave her what they could.

Paper piled up on one wall of her hut, in stubby pencil lines and precise ink: graphs of frequencies, Doppler shift curves, decibel readings. She pinned them up one by one until the wood disappeared.

On the floor beneath the charts, she laid out small wooden blocks carved into rough hull shapes, little wooden screws, tiny microphones. She built a toy ocean on the planks, a model to think with.

Her husband, Samuel, worked in a neighboring building on radar electronics and proximity fuses. At night they walked home under blackout curtains and compared puzzles.

“How do you fool a machine that listens?” Sam would ask after a day wrestling with circuits.

“Make it hear the wrong thing,” Joan would say.

Back in her hut the next morning, wrapped in an extra sweater against the draught, she turned that line over and over.

An acoustic torpedo didn’t care about flags. It didn’t know which ship was friend or foe. It was a mechanical predator, head full of microphones, running on mathematics and mechanics.

If you couldn’t stop it from listening, maybe you could change what it heard.

The Royal Navy’s own research staff had tried a grab bag of ideas.

Underwater flares. Noise bursts. Cancellation waves meant to erase the ship’s own signature.

Nothing worked.

The sea swallowed energy fast. Sound attenuated with distance. Moreover, the torpedo’s own logic—that simple wiring that told its rudder, “turn toward the louder side”—wasn’t fooled by tricks that just made things messy.

You needed something louder than a destroyer. Something that roared across the same frequency band, but from somewhere the torpedo would do no harm.

The idea must have sounded childish to some: tow a noisemaker behind a ship, like tying tin cans to a wedding car.

Childish or not, Curran started sketching.

5. “Louder Than Any Engine Alive”

She drew pipes first.

Hollow steel cylinders, open at both ends, tied together in frames. Water moving through them would rattle and hammer, especially if interrupted by blades or fins.

Add chains. Add holes to make turbulence. Encase the whole contraption in a cage so it didn’t tear itself to pieces.

Attach the thing to a cable behind a ship and let the propeller wash do the work.

Noise. Lots of it.

She built a version no bigger than a breadbox and lowered it into a test tank, a long concrete pool half full of chilled water. A motor at one end pumped water past the device. Hydrophones—underwater microphones—sat in the tank at measured distances.

When she spun the pump up, the device shook against its tethers like a maddened animal.

The noise in her headphones wasn’t music, it was chaos—clattering, roaring, a scrape and crash of frequencies right where the Germans’ torpedoes liked to feed.

It drowned the recorded hum of a ship’s screw completely.

She smiled, just a little.

Engineers who wandered past stuck their heads in the hut and winced.

“Sounds like the devil’s own bagpipes,” one muttered through his teeth.

The name stuck.

In the Admiralty paperwork, the project was code-named “FXR.” In the messes and on the decks, men would call it “Foxer,” a word that sounded like trickery and noise mashed together.

The first full-sized unit, no longer breadbox-sized but the size of a steel trash can, went over the side of a test vessel off Portland Harbor on a January day that felt like the world had forgotten how to be warm.

On deck, sailors in duffel coats and watch caps eyed the thing as it clanked on the davits. It looked like junk—pipes, chains, plates bolted together in ugly frames.

When they dropped it, the ship’s stern jerked like it had snagged on a reef. The tow cable snapped taut and began to hum as if alive.

The water behind the destroyer boiled with bubbles and spray.

In the sonar hut, the operators frowned as their displays went from clear to clogged. The ship’s screw signature vanished under a thunder of metallic screams.

“Bloody hell,” someone said.

From the test boat a mile astern, another crew listened through their own hydrophones. All they could hear was the Foxer.

No ship’s beat. No other sound.

The dummy torpedoes they dropped into the water that day spiraled toward the roar every time. They curved away from the quiet line of the tow ship’s hull and chased the decoy until their batteries died and they sank, harmless.

The Foxer worked.

It also blinded the ship towing it.

Escort captains, when briefed, protested. “How are we supposed to fight if we can’t hear anything?” they asked. “Sonar is our only chance of catching the U-boat before it kills us.”

Curran’s answer was blunt.

“Better deaf than dead,” she said.

The Admiralty, staring at loss curves that looked like heart attacks, agreed.

They ordered Foxers into production.

6. The Roar Behind the Convoy

On Christmas Eve 1943, in weather that would have made a landlubber swear off the sea forever, a convoy left Liverpool under low clouds.

The destroyers HMS Fame and HMS Inconstant trailed something new behind them—chains and frames they could not see, twisting and shrieking in the black water.

On the plotting table, the convoy had a designation and a path. On the ocean, it was a line of lights that winked as waves passed, each lamp a promise of cargo and human beings inside.

In the control room of U-275, a German Oberleutnant named Schumacher listened on his hydrophones as the sounds of the convoy washed in.

Merchant screws, slow and heavy.

Escort screws, faster, harder.

And behind them, something he had never heard before.

It was as if someone had thrown a piano into a crusher and then turned the volume up. A crashing, grinding, shrieking racket that rolled across the headphones, louder than any propeller.

Schumacher frowned.

Static? Malfunction?

He checked his equipment again. No. The noise was out there, real. Behind the escorts. Following them like some mechanical phantom.

He made his choice.

The G7es torpedo slid into the tube. Men slammed doors, spun wheels. Compressed air hissed.

The weapon shot into the Atlantic and dove.

In the British destroyer’s sonar room, a rating’s hand jerked at a new sound in his headphones—a rising whine, faint and then growing.

“Torpedo bearing green two-oh!” he shouted.

The captain ordered a sharp turn, screws biting the sea harder as the helm answered.

The whine in the water shifted.

And then, seconds later, a deep boom rolled up from astern.

The destroyer shuddered—not from impact, but from the distant concussion.

On the fantail, men stared back at a plume of water and bubbles well behind them, in the line of the tow cable.

The Foxer had screamed louder than the ship’s own heart. The torpedo, in love with noise, had swerved off target and died chasing trash.

The destroyer plowed on.

The next day, a terse signal reached London.

DEVICE FXR EFFECTIVE. ONE TORPEDO DECOYED.

In Joan Curran’s hut on the Dorset coast, an Admiralty liaison handed her a thin slip of paper.

She read it through once, then set it down on the bench and leaned against the table, suddenly aware of how tired she was.

One sentence. One torpedo.

A hundred men who’d sleep in their bunks that night instead of in the cold dark.

Physics, writ in steel and water.

She picked up her pencil and went back to her graphs.

The war did not pause for congratulations.

7. Filling the Ocean with Lies

The Foxer spread.

Within weeks, production lines across Britain turned out decoys: frames of steel pipes, chains, plates. Each unit looked like something thrown haphazardly into a scrapyard. Each one had to be built to exacting specifications of size and hole placement to scream at the right frequencies.

Convoy JW 58 to Russia sailed with Foxers rattling behind its escorts.

ONS 29 across the Atlantic, CU 49 with fuel, HX 300—the largest convoy of the war with over 160 ships—all dragged chains that churned the sea into so much angry water.

Out in the North Atlantic, the soundscape changed.

Hydrophone operators on U-boats, once used to picking out the steady thrumming signatures of individual ships, found their ears filling with clamor.

Noise. Constant, brutal, unstructured noise.

Destroyer screws became whispers behind the roar.

Torpedoes tuned to lock onto the loudest source followed the Foxer instead of the hull. They veered away from their supposed prey and exploded in turbulence miles behind.

Some U-boat commanders, after losing expensive weapons to metallic ghosts, refused to fire acoustics at all. They switched back to straight-running fish when they could. Others cursed and guessed and hoped.

In escort messes, men grumbled about the Foxer’s downside.

Towing the thing made the ship vibrate. The jury-rigged brackets shook. Dishes rattled in racks. Bulkheads thrummed.

Sonar screens went from clean to snow.

“You can’t hear a bleed’n’ thing with that thing out,” one chief sonarman said. “Might as well stuff cotton in your ears and go for a stroll.”

But as one sign in HMS Dakins’ wardroom reportedly put it:

IF YOU CAN STILL HEAR IT,

YOU’RE STILL ALIVE.

The numbers backed the sentiment up.

In the autumn of ’43, the charts at the Admiralty had shown shipping losses climbing—forty-five merchant vessels sunk in a single month.

By March 1944, the line bent down.

Shipping losses fell to their lowest of the war. Six ships that month instead of dozens.

Not zero. The North Atlantic was still a kill zone. Storms still took ships. U-boats still sank ships with straight-runners or from close-in attacks.

But the acoustic terror—the silent homing death—had lost its edge.

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest campaign of the war, had tilted.

Commanders credited new escort tactics, long-range aircraft, code-breaking, and all the other tools that had slowly strangled the U-boat arm.

Somewhere down the list, in a footnote, they mentioned an “acoustic decoy device developed by TR&E.”

Joan Curran’s name didn’t appear.

She didn’t ask that it should.

8. Ghosts in the Headphones

In Germany, Admiral Karl Dönitz read his own charts and saw the disaster from the other side.

The number of U-boats that failed to return rose steadily. Forty in June 1944 alone. Thirty thousand submariners would never see land again by war’s end.

The hunters had become the hunted.

German engineers scrambled to claw back the advantage.

They modified the G7es, trying to teach it to ignore the loudest noise and seek a steadier beat—the so-called T11 Zaunkönig II, a counter-countermeasure envisioned to pierce through the Foxer’s racket.

Tuning analog circuits in a torpedo was harder than designing them in a quiet lab. Getting enough of them into enough boats in time was harder still.

The war was already slipping away. Normandy. The Russian advance in the east. The cracking of Italy.

Foxer’s children, meanwhile, grew more refined.

At sea, tactical officers adjusted formations to compensate for the decoys’ sonar blinding effect. Ships towed Foxers in specific patterns, staggered distances, to leave listening gaps where other escorts could hear.

In the huts on the Dorset cliffs, Curran and her colleagues tweaked pipe diameters, hole patterns, chain lengths. New variants—FXR2, FXR3, “Fanfare,” “CAT”—altered the sound, the frequency mix, the durability.

The principle stayed the same: when the enemy pointed an ear at you, overwhelm it with a louder lie.

In a quiet moment, leaning against the doorframe of her hut with a cup of rapidly cooling tea, Curran watched a test rig churn the tank water into froth. The hydrophones registered a familiar wall of noise.

Somewhere out in the Atlantic, she knew, dozens of full-sized versions were doing the same thing on a much grander scale.

She wrote a line in one of her reports, the ink neat but the sentiment fierce:

“Where perception is a weapon, deception must be the shield.”

The sentence described sound waves and frequency bands.

It also described her war.

9. The Men Who Never Knew Her

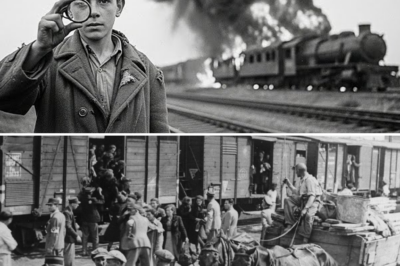

There’s a photograph from late 1944—black and white, of course—that shows a convoy arriving in Liverpool.

Men lean over rails, waving at the docks. Tugs bustle around them. On shore, cranes like skeletal arms reach out to grab cargo that will end up in factories and depots and, eventually, on battlefields across Europe.

You can’t hear a photograph.

But if you could press your ear up against that image, somewhere in the mix of fog horns and shouted orders, you might hear a memory of metal screaming in the ship’s wake.

Sailors named their Foxers like they named their ships.

Old Growler. Metal Mary. The Screamer.

When one jammed or snapped its tow cable and went silent, men felt a new kind of fear. Not of the roaring clatter, but of its absence.

Quiet used to mean peace.

Out there, for years, quiet had meant death.

In the control room of a British escort, a chief engineer wrote in his log after yet another failed torpedo attack, “The quiet is worse than the noise. In silence, you remember what the ocean used to take.”

The sailors on those ships didn’t know the name of the woman who had put that noise behind their sterns.

They knew some boffin down in a hut had cooked up something that made German torpedoes run stupid. They heard rumors of “mad scientists” with wires and bats and vacuum tubes.

They rarely pictured a young woman with a Welsh accent tightening a bolt on a frame in a lab coat smeared with oil.

Curran moved on even before the war ended. In late ’44 she transferred north to join her husband in Scotland, working on another set of secret problems—atomic detection, nuclear research.

Her Foxer files went into cabinets stamped SECRET. Her decoys stayed in use, shrieking in the deep, protecting ships she’d never see.

When the war finally ended—VE Day, the crowds in London, the headlines and the bells—she listened to the celebrations and thought not of parades but of charts.

Loss curves that had flattened. Lines of zeros under “Ships Sunk” for convoys that would once have been slaughtered.

Somewhere, men were home with their families because a torpedo had chased the wrong sound.

10. After the Noise

Peace is quieter, but not always gentler.

The convoys stopped running. Shipyards slowed. The labs along the coast were emptied, their equipment either cannibalized for peacetime projects or sealed away until someone in a later war might need them.

The files stayed closed for decades.

Official histories of the Battle of the Atlantic came out, thick books with pictures of admirals, maps of convoy routes, tales of code-breakers and brave captains and crucial battles.

In the index of one such volume, published years after, the name “Curran, Joan” appeared once, spelled slightly wrong in a footnote about radar and “Window.”

Foxer rated a paragraph or two.

That was how it went.

Awards went to men in uniform, committees, institutions. That didn’t bother her much, or so she insisted when friends brought it up.

“I was lucky,” she said once. “Most of us never see our work save anyone. I did.”

She and Samuel helped build Britain’s postwar nuclear program. The world’s dangers shifted from torpedoes to missiles, from portholes to mushroom clouds.

But the principle she’d nailed down in those freezing huts by the sea refused to die.

When the Cold War slid the planet into a new kind of chill, navies on both sides of the iron curtain quietly fitted their submarines with noise-makers—compact, high-tech descendants of Foxer. Sleek canisters that could be dumped overboard to spin and scream, drawing modern acoustic torpedoes away.

Different tech. Same trick.

If the enemy listens, lie louder.

In 1993, almost fifty years after she’d first sketched a pipe and a chain on a scrap of graph paper, she received some formal recognition for her work on radar countermeasures. Ceremony, speeches, nice handwriting on nice paper.

Foxer barely rated a mention.

She didn’t correct the oversight.

She died in 1999, aged eighty-three, the arc of her life crossing from horse carts and crystal sets through the most mechanized slaughter in human history, into an age where her grandchildren could pull a computer from their pocket that would have made the wartime boffins gape.

The ocean had long since fallen quiet again, at least to human ears on deck.

Deep below, in a world still full of military machines, the echoes of her ideas rolled on.

11. Why It Matters on This Side of the Ocean

It would be easy, sitting in an American living room decades later, to file all of this under “British history.”

Joan Curran was Welsh. Her lab was on the Dorset coast. British convoys streamed into Liverpool and Glasgow. British destroyers with “HMS” on their sterns towed Foxers.

But the ocean doesn’t care about passports.

Those convoys carried American wheat and steel and oil. They carried Lend-Lease cargo from US ports. They carried Jeeps and bombs and radios plenty of American factories had stamped out.

On their decks, more and more as the war went on, were American soldiers. GI’s leaning on railings, duffel bags at their feet, watching gray waves race by on their way to Europe.

Every ship that made it through the Black Pit meant more than a British headline. It meant food in New York and London, tanks in Patton’s army, planes in the 8th Air Force, fuel in the refueling trucks that fed the Red Ball Express.

Every ship that didn’t, every Liberty ship that went nose up and down in fire, meant some family in Kansas or Kentucky or Ohio got a telegram with a line that began, “We regret to inform you…”

The new German torpedoes didn’t care if the hull they hit was painted gray or black. They just listened and killed.

Curran’s invention didn’t care either.

It screamed behind British and American escorts alike. It protected Canadian ships, Norwegian ships, Free French ships, stragglers and flagships.

It was one more reminder that the war in the Atlantic was an Allied war in the broadest sense—a joint venture in survival.

And that sometimes, the quietest person in the room, in the smallest hut on the edge of a foreign coast, makes the biggest difference to people who will never know her name.

12. The Last Echo

Today, if you walk into a naval museum—one of those places with polished cases and plaques and the smell of old paint—you might see a weird piece of gear hanging behind glass.

It looks like junk. Rusted pipes, flanges, a length of chain. The label underneath might read something like:

ACOUSTIC DECOY, TYPE FXR “FOXER”

ROYAL NAVY, 1943–45

Most visitors glance and move on. The battleship models and the sleek jet fighters grab more attention.

If you linger, if you imagine that ugly contraption not as metal on a hook but screaming in black water, you might feel the hair on your arms stir.

You might picture a dark Atlantic night, a convoy crawling under low clouds, a destroyer rolling in the swell with that thing thrashing behind it.

You might picture a German torpedo racing through the water, microphones hungry, turning and re-turning toward the loudest thing it can hear.

You might imagine it curving away from the destroyer’s hull, away from the crowded mess decks and the sonar hut and the bridge, and plunging into the roar.

You might hear, in your mind’s ear, the boom farther astern, the cheer on deck, the sigh in some communications hut when the convoy’s arrival signal comes in: ALL SHIPS SAFE.

And if you listen very carefully in that museum hush, between the murmur of other visitors and the faint hum of air conditioning, you might hear something else.

A quiet Welsh voice, a long time ago, saying to a skeptical officer:

“It hunts by hearing. So let’s give it something else to hear.”

In a war full of giant machines and famous names, that sentence is one of the reasons free nations sit where they do today.

Hitler’s U-boats were winning.

Until one woman’s invention made them chase ghosts.

THE END

News

CH2 – Why One Captain Used “Wrong” Smoke Signals to Trap an Entire German Regiment

The smoke was the wrong color. Captain James Hullbrook knew it the instant the plume blossomed up through the shattered…

CH2 – On a fourteen-below Belgian morning, a Minnesota farm kid turned combat mechanic crawls through no man’s land with bottles of homemade grease mix, slips under the guns of five Tiger tanks, and bets his life that one crazy frozen trick can jam their turrets and save his battered squad from being wiped out.

At 0400 hours on February 7th, 1945, Corporal James Theodore McKenzie looked like any other exhausted American infantryman trying not…

CH2 – The 12-Year-Old Boy Who Destroyed Nazi Trains Using Only an Eyeglass Lens and the Sun…

The boy’s hands were shaking so hard he almost dropped the glass. He tightened his fingers around it until…

CH2 – How One Iowa Farm Kid Turned a Dented Soup Can Into a “Ghost Sniper,” Spooked an Entire Japanese Battalion off a Jungle Ridge in Just 5 Days, and Proved That in War—and in Life—The Smartest Use of Trash, Sunlight, and Nerve Can Beat Superior Numbers Every Time

November 1943 Bougainville Island The jungle didn’t breathe; it sweated. Heat pressed down like a wet hand, and the air…

CH2 The Farm Kid Who Learned to Lead His Shots: How a Quiet Wisconsin Boy, a Twin-Tailed “Devil” of a Plane, and One Crazy Trick in the Sky Turned a Nobody into America’s Ace of Aces and Brought Down Forty Japanese Fighters in the Last, Bloody Years of World War II

The first time the farm kid pulled the trigger on his crazy trick, there were three Japanese fighters stacked in…

CH2 – On a blasted slope of Iwo Jima, a quiet Alabama farm boy named Wilson Watson shoulders a “too heavy” Browning Automatic Rifle and, in fifteen brutal minutes of smoke, blood, and stubborn grit, turns one doomed hilltop into his own battlefield, tearing apart a Japanese company and rewriting Marine combat doctrine forever

February 26, 1945 Pre-dawn, somewhere off Eojima The landing craft bucked under them like an angry mule, climbing one…

End of content

No more pages to load