The German Shepherd would not stop pulling at the American sergeant’s sleeve.

It had started subtle: a tug at the cuff of Sergeant Robert Hayes’s jacket as his squad moved through the wet French woods. June 1944. South of Carentan. The forest was all slick mud and shell-splintered trees, the air still holding the faint chemical bite of the last bombardment.

At first, Hayes had shrugged the dog off, too focused on the quiet.

Silence in a combat zone was never real. It was just the space where you waited to find out who was going to move first.

The Shepherd—big, black-and-tan, ribs just starting to show under his coat—kept at it. He’d dart ahead ten yards, stop, look back, then run back to Hayes and grab his sleeve again. Teeth grazed wool and skin, never quite biting, frantic but careful.

“Sergeant,” Private Morrison whispered from behind him, “I think it’s trying to lead us somewhere.”

The dog barked once. Not a warning bark, not a challenge. Sharp. Urgent. Then it spun and disappeared deeper into the trees.

Hayes’s hand slipped automatically to the stock of his M1. Every nerve in his body voted no. German snipers loved tricks. They’d dangle something in front of Americans—a wounded man, a crying civilian, a stray dog—and wait for sympathy to drag them into a kill zone.

The patrol was six men: Hayes, Morrison, Chen, two riflemen from Baker Company, and a radioman whose face was more freckles than skin. They were already too far forward for comfort, shoulders tight under the weight of unseen rifles.

“Could be bait,” Chen murmured.

“Yeah,” Hayes said. “Could be.”

But the dog’s behavior was all wrong for bait. No training, no calculated distance. Just that wild, obsessive urgency. When it looked back, ten, twenty yards away, its eyes hit him like a hand on his chest.

Not fear.

Pleading.

Something inside him shifted. Hayes had grown up around farm dogs in Iowa, dogs that understood things before people did. He recognized the look.

“All right,” he said. “We follow him. Weapons ready. If this is a trap, we make it the worst one they ever set.”

They pushed into thick underbrush, branches slapping at their uniforms. The Shepherd stayed twenty yards ahead, weaving around trees, stopping at every rise to check that they were still coming. The further they went, the louder Hayes’s training screamed.

Away from our lines. Deeper into their territory. Into the teeth of it.

Morrison breathed hot air into his gloves. “Feels like we’re chasing a ghost, Sarge.”

“Ghosts don’t drool on your sleeve,” Hayes said, but his voice was tight.

Then, as suddenly as the dog had started, he stopped.

He sat down beside a twisted pile of branches, half-hidden in the undergrowth. For a second, Hayes saw nothing but leaves and blown dirt.

Then his eyes caught the boot.

Gray wool, German issue. A slashed, blood-caked trouser leg. The shape resolved into a body: a young man in a field-gray uniform, crumpled like a discarded coat. Blood had dried dark and stiff across his chest. His face was the color of melted candle wax, lips cracked and colorless.

The dog lay down beside him, pushing his muzzle against the man’s shoulder with a low whine.

“Jesus,” Morrison whispered. “He’s a Jerry.”

“No kidding,” somebody muttered.

Hayes dropped into a crouch, rifle up, heart pounding harder now than it had under shellfire. A wounded enemy sniper out here could still be dangerous. He scanned the trees, expecting the crack of a rifle at any second.

“Watch the perimeter,” he snapped. “360. I want eyes on every tree.”

Boots shifted in the muck as the squad fanned out. The forest held its breath.

Hayes leaned closer.

The German wasn’t dead. Not yet. His chest rose barely, each breath shallow and ragged. Eyes fluttered under lids that looked bruised from the inside. When they opened, just a slit, Hayes saw the quick calculation there—the flinch of recognition at American helmets and dark silhouettes.

Then something worse than fear.

Acceptance.

The boy—because he was a boy, Hayes realized, nineteen at most—let his eyes close again, as if this was just the last card in a bad hand he’d already seen the end of.

The dog whined louder, nose nudging the sergeant’s sleeve. Hayes finally understood what the Shepherd’s frantic tugs had been saying for the last ten minutes.

Please. Before it’s too late. Please.

He looked at the rifle half-buried under leaves beside the German. A scoped Mauser. Sniper rifle.

This kid had probably killed Americans. Maybe men Hayes knew. Men he was responsible for.

Behind him, Morrison spoke low. “We can’t just leave him, Sarge.”

“He’s a sniper,” one of the riflemen—Connelly—said flatly. “See that glass? How many of ours you figure he put on the ground? We got a job. He ain’t it.”

“The job is getting more of our guys home alive,” Hayes said automatically. But the words weren’t matching the weight he felt.

His gaze drifted back to the dog.

The Shepherd’s amber eyes were locked on his, wide and shining. No language, no allegiance, nothing but raw, desperate plea.

Hayes exhaled slowly, a cloud of white in the damp air.

“You know what they taught us about you?” he muttered to the German, half to himself. “Same thing they taught you about us, I bet.”

He thought about his own dog back home, an old mutt who slept on the porch of the farmhouse in Iowa, who had once refused to leave Hayes’s side when he’d come home from his first hunting accident with a sliced hand.

This German Shepherd had dragged an enemy squad through a forest instead of running. Had stayed for two days, if the dried blood was any sign. Had not left even when every instinct should’ve told him to.

Hayes made his decision.

“Nobody dies alone,” he said quietly. “Not on my watch.”

He raised his voice. “Morrison, get the stretcher. Chen, check your kit for plasma. Move.”

Connelly stared at him. “We patch him up, that’s one more Kraut we gotta feed and guard instead of—”

“Instead of what?” Hayes snapped. “Instead of letting him bleed out under a pile of sticks? He’s not an objective, Connelly. He’s a human being. We’re not leaving him.”

The dog let out a sound that might have been a sigh, head dropping briefly to the German’s chest as if finally, finally, someone had understood.

Three months earlier, in Munich, the posters on the wall had shown a very different American.

Obergefreiter Dieter Hoffmann stood in the training hall, shoulders back, hands at his sides, staring up at the face of his enemy.

The American on the poster was all exaggeration: sloping forehead, heavy jaw, crooked teeth bared in a snarl. His hands were claws. His boots were planted on the bodies of dead German children. Above him, in black Gothic letters: Sie kennen keine Gnade.

They know no mercy.

“This is your enemy,” the instructor had said. His voice was dry, matter-of-fact, like someone reading from a timetable.

“Americans torture prisoners for sport,” he went on. “They cut off ears for trophies. If you are captured, you will be paraded through their streets, beaten, starved. Better to save your last bullet for yourself.”

Dieter was nineteen.

He had been recruited straight out of the Hitlerjugend into sniper school. His file said he had good eyes, good hands, patience. He could lie motionless for hours during field exercises, barely breathing, waiting for a rabbit to step into his scope.

“You have the temperament,” his instructors told him. “Cold blood. That is what separates a sniper from ordinary soldiers.”

Dieter didn’t feel cold-blooded.

He felt terrified.

His family’s apartment in Munich’s Glockenbach district was small and always slightly damp, the wallpaper peeling. His father, a postal clerk missing his left arm from the last war, had pulled him aside the night before deployment.

“Whatever they tell you about the Americans,” his father whispered. The shadows in the hallway seemed to listen. “Remember, soldiers are soldiers. The ones giving orders…” He trailed off, eyes flicking toward the thin wall, toward the ever-present possibility of listening ears. “Be smart, Dieter. Stay alive.”

Dieter had nodded, not really understanding. His father had been gassed at Verdun. Had seen Americans up close. But the new propaganda, the relentless films and slogans and posters, painted a different picture.

These Americans were different, they were told. The soft doughboys of his father’s youth had been replaced by a new, brutal breed. Savage, degenerate, dangerous.

Then Blitz walked into his life and made everything messier.

The Shepherd arrived during Dieter’s final week of sniper training. He was three years old, big-boned and powerful, with a coat that caught the light like burnished metal. He had been bred for the army—scout dog, attack dog, messenger, the usual roles.

But Blitz had washed out.

“Too soft,” one trainer said. “Gets attached. Won’t bite when he’s supposed to.”

In a fit of cynical humor, they’d assigned him to Dieter. The sensitive sniper. The gentle failure of a war dog.

“Perfect pair,” the instructor had laughed. “Two soft hearts. Maybe together you make one hard one, eh?”

Dieter had reached out and Blitz had pressed that massive head into his hand, leaning into the touch with a sigh.

That was it.

Blitz slept by his bunk at night, warm and solid. During exercises, he trotted at Dieter’s heel, ears flicking, nose constantly testing the wind. When artillery simulators went off on the training field, Blitz pressed against Dieter’s side as if he could absorb some of his handler’s fear.

When they shipped out to France, the only constant was the dog at his side.

Villages blurred past as the German army fell back, regrouped, fell back again.

By early June, south of Carentan, Dieter’s unit had dug into a forest, thin line against a tidal wave. The Allies had come ashore in Normandy like a storm. The German army was splintering under the strain.

Dieter had killed four men in three days.

He could still see them if he closed his eyes: the flash of a face in his scope, the squeeze of the trigger, the distant jerk as a body folded. Training said good shot. Something else inside him contracted a little more each time.

After each shot, Blitz would find him in his hide and press close, warm weight anchoring him to the ground while Dieter’s stomach rolled. Once, he’d actually vomited into the dirt beside his rifle. Blitz had licked his cheek afterward, as if to erase the taste of it.

“They will kill us all,” one of the older soldiers had said around the cook fire one night, gesturing vaguely west. “Not today, maybe. But soon. We’re just buying time.”

Time ran out for Dieter the way it often did in that war.

With thunder.

The bombardment hit at dawn.

American 155s walked their shells through the forest with mechanical precision. One moment, Dieter and his spotter were in their carefully concealed nest overlooking a narrow road. Blitz lay curled at his feet, ears twitching at every distant boom.

The next, the sky caved in.

The first rounds landed two hundred meters away, tree trunks bursting into jagged spears. The second volley was fifty meters closer, the shockwave slamming against their eardrums, turning air into something thick and heavy.

“Raus!” the spotter shouted, scrambling out of the hide. “Move!”

Dieter grabbed his rifle, his pack. Blitz was already up, hackles high, barking in a pitch Dieter had never heard before—panic, raw and high.

They ran.

Around them, the forest dissolved into hell. The ground heaved like the deck of a ship in rough seas. Trees exploded, shards whistling through the air. A branch bigger than a man slammed into the ground where Dieter had been standing seconds before.

Smoke poured in gray sheets, choking. The air tasted like metal and burning earth.

Dieter lost sight of his spotter in the chaos. One second he was there, a dark shape ahead; the next, he was just gone, swallowed by smoke and fire and confusion.

“Blitz!” Dieter coughed, eyes watering. “Blitz, hier!”

The dog materialized at his side, bumping his leg, guiding him blindly between trees.

Then a shell landed directly behind him.

There was a moment—one surreal fraction of a second—when everything went quiet, colors sharpening, the forest frozen. Dieter felt himself leave the ground, weightless, as if he’d stepped off a cliff in a dream.

Then the tree trunk caught him.

He slammed into it sideways. Pain exploded along his ribs, sharp and white-hot. Something deep inside tore. He tumbled to the ground and lay there, air punched out of him, mouth opening and closing uselessly.

He tried to inhale. Fire answered.

Blitz barked. Once. Twice. The sound warbled strangely in Dieter’s ringing ears.

Men were shouting somewhere. German voices, panicked, falling back. Boots thudding past. No one stopped.

The bombardment rolled on, a relentless machine.

Time blurred after that.

When the last shell fell and the forest settled into a smoking ruin, Dieter tried to move his arm and felt nothing but distant pressure. He tried to call out and tasted blood instead.

His father had described this taste once, at the kitchen table. Metallic. Sweet in an awful way.

“The taste of your own lungs,” he’d said, and Dieter had swallowed hard and changed the subject.

Now he knew exactly what his father meant.

He could feel air bubbling in his chest, each breath a wet, rattling effort. One lung, maybe both, had been punctured. Ribs cracked. Maybe spine. Pain came in waves that washed everything else away.

Boots pounded past him, retreating. He saw gray uniforms through half-closed eyes. Some men glanced down. Most didn’t. A few looked straight at him, face pinched in a way that meant they’d already filed him as dead.

Leaving him there wasn’t cruelty. It was math.

Within minutes, the German voices faded.

The forest went strangely quiet, only the crackle of distant fires and the occasional groan of a dying tree branch breaking under its own weight.

Blitz pressed himself against Dieter’s side, whining, eyes wide and glassy. When Dieter tried to lift a hand, it barely twitched.

Two days bled together.

Blitz never left.

He brought water in his mouth, careful, somehow, to carry without swallowing. He’d disappear into the ruined woods, come back with muzzle dripping, and let water spill onto Dieter’s cracked lips. Dieter would drink as much as he could before coughing it back up, pink with blood.

At night, as cold settled into the broken forest, Blitz stretched his body over Dieter’s chest, sharing warmth, steady heartbeat thudding against shattered ribs.

Dieter’s mind frayed under fever and shock.

Sometimes he was back in his bed in Munich, listening to his mother hum in the kitchen. Sometimes he saw, with cruel clarity, the faces of the men he’d shot through his scope, the way their bodies dropped. Sometimes he heard his father’s voice at Verdun overlapping with the thunder in the forest.

But always, anchoring him, was the weight of Blitz.

On the morning of the third day—if it was morning; time had lost its edges—Dieter couldn’t open his eyes. They felt glued shut. He tried to say Blitz’s name and managed only a dry rasp.

He felt the dog’s warmth shift.

Blitz stood up.

Tags jingled softly as he moved away.

He’s leaving, Dieter thought, oddly calm. After everything, the dog was leaving. Of course he was. Even animals knew when to cut their losses.

Loneliness swept through him with a force that startled him more than any pain. Not fear of death. Fear of dying alone.

Then everything slid away.

He woke to English.

At first the words were just sound: harsh consonants, cutting through the fog. Then one name rose above the others.

“Blitz,” an American voice said, incredulous. “What is it, boy? What are you doing out here? Christ, look at him go.”

“Sergeant, he’s trying to drag you.”

“Okay, okay. I’m coming. Easy, boy.”

Light burned the backs of Dieter’s eyelids. He forced them open a fraction.

The helmets were wrong. Not the rounded, familiar German coal-scuttle shape, but smoother, flared rims. American.

Five, maybe six figures. Rifles unslung. Faces smeared with dirt and fatigue.

“This is it,” Dieter thought. “They’ll finish it. They’ll put a bullet in me and move on.”

He had been told, over and over, what Americans did to German prisoners. This would be merciful, comparatively.

One of the soldiers—tall, broad shoulders, sergeant’s stripes on his sleeve—knelt next to him and peered into his face.

“How old are you, son?” he asked in English.

It took Dieter a second to remember the words. School lessons from another lifetime floated up.

“Neun…zehn,” he croaked. “Nineteen.”

The sergeant’s expression flickered. For a heartbeat, Dieter saw something that looked almost like recognition.

He braced himself for disgust, for the rifle muzzle pressing to his temple.

Instead, the sergeant said, very quietly, “Nobody dies alone. Not on my watch.”

He turned his head. “Morrison, stretcher. Chen, see if we got any plasma left. Move it.”

Dieter’s brain couldn’t keep up.

This was wrong. Americans did not save German snipers. They did not call them son in a tone that sounded so…normal.

The sergeant unscrewed his canteen and lifted Dieter’s head with rough, careful hands.

“Water,” he said, as if explaining to a child. “Slow. Easy.”

Cold touched Dieter’s lips, shocking his cracked skin. He choked, coughing up more blood. The sergeant adjusted the angle, patiently waiting until Dieter managed a tiny sip.

“Good,” the man said. “Again.”

The water was the best thing Dieter had ever tasted.

Morrison arrived with a folding canvas stretcher. Private Chen, short and compact under his gear, had a plasma bottle in his hands, rubber tubing already uncoiled. They moved with an efficiency Dieter had only seen in his own medics treating German wounded.

“Punctured lung for sure,” Chen muttered, fingers searching for a vein in Dieter’s arm. “Probably more. We get him to the aid station, maybe he’s got a chance.”

“Why are you doing this?” Dieter tried to ask. It came out as a mangled whisper.

None of them seemed to hear.

They rolled him onto the stretcher as gently as they could. Every movement was a knife. Dieter couldn’t help the cry that escaped him. The dog pressed his nose against Dieter’s hand, whining, as if apologizing for the pain he couldn’t prevent.

“I know,” the sergeant said, voice low, hand gripping Dieter’s shoulder through the uniform. “I know it hurts. We’ve got you.”

Those words—We’ve got you—made less sense than anything else.

We were Americans. You was a German sniper. There was no we there.

They started walking.

Blitz trotted beside the stretcher, glued to Dieter’s side. When one of the riflemen moved too close, the dog’s lip curled, not in a threat, but a warning: Don’t hurt him. The soldier backed off automatically.

“Loyal dog,” Morrison observed between huffs of breath.

“Probably the only reason this kid’s still alive,” Hayes said. “Look at his muzzle—still damp. Where the hell did you find water, boy?”

He reached down briefly, fingers brushing Blitz’s neck.

The dog’s tail wagged once, quick and tentative, before he refocused on Dieter.

They offered Blitz a scrap of hardtack at one point. The dog sniffed it, ignored it, and licked Dieter’s fingers instead. He had priorities.

The walk to the aid station took forty minutes.

Each step was its own small eternity. The woods thinned. Artillery rumbled dull and distant. The air smelled less of smoke and more of raw earth and crushed weeds.

Every time Dieter surfaced from the fever haze, the same scene greeted him: Americans carrying him carefully, Blitz beside him, Hayes checking the plasma drip, adjusting the blanket somebody had thrown over him.

“Why?” the question circled, relentless.

Why would your enemy carry you like this when your own comrades had stepped over you?

Why?

The aid station was a French farmhouse halfway between destroyed and functional.

Somebody had painted a red cross on the barn door. The main living room had been turned into a ward, cots jammed so close together that the medics had to turn sideways to pass. The barn served as a surgical theater, the air inside sour with blood and antiseptic.

When Hayes’s patrol shouldered their way in with the stretcher, the place was already humming—moans, shouted orders, the constant low murmur of battlefield medicine.

“Another one?” a medic in a stained white apron called out. He ran a quick, practiced eye over Dieter’s uniform. “German.”

“Sniper,” Hayes said. “But still breathing.”

The medic shrugged. “Breathing’s my jurisdiction, not nationality.”

He lifted Dieter’s eyelid, checked his pulse.

“Pneumothorax,” he muttered. “Ribs like broken kindling. Possible internal bleeding. Get Captain Bradford.”

Captain Bradford, Medical Corps, arrived moments later. His face was drawn but focused, eyes clear as he assessed the mess of Dieter’s chest.

“He needs surgery now,” Bradford said. “We wait, he drowns in his own blood. Let’s go.”

Dieter’s stretcher pivoted toward the barn.

Blitz followed.

“Get the dog out of here,” a nurse snapped, moving to block him.

“He stays,” Hayes said, sharper than he meant to. “He led us to the kid. Probably kept him alive in the woods. He’s earned it.”

Bradford hesitated, then nodded. “Fine. As long as he stays out of the sterile field. We’ve operated in worse company.”

Blitz settled just outside the operating area, eyes never leaving Dieter as they lifted him onto a rough wooden table.

As anesthesia took hold, Dieter’s last clear thought was not about the knife or the bright light or the terror of being in enemy hands.

It was the sergeant’s voice, steady and sure.

“You’re a soldier, son. Same as us.”

The propaganda posters on the training hall wall in Munich burned away like paper under a match.

When he woke again, it was to sunlight and clean bandages and a pain that had changed character.

His chest still hurt, but it was no longer drowning him. Breaths still pulled at his ribs in sharp lines, but they came. His head felt like it was stuffed with cotton.

The barn was gone. He was in the farmhouse, in a row of cots. The ceiling beams were low. Flies buzzed lazily somewhere nearby.

He turned his head.

Next to his bed, Blitz slept curled up, head on his paws, breathing slow and deep.

“You’re awake,” a voice said in German.

Dieter blinked.

A medic stood beside him, uniform the same khaki as the others but name tape reading Schmidt. His accent was German softened by years of English.

“Your dog wouldn’t leave,” Schmidt said. “We tried three times to bring him outside. He growled. Not like he was going to attack—just…arguing with us. Captain Bradford finally said to let him stay. Said he’d never seen loyalty like that.”

Dieter tried to say thank you and managed a croak. Schmidt lifted a canteen to his lips, helping him drink.

The next three days dismantled his entire world.

German wounded lay in cots alongside American wounded. Different uniforms. Same bandages. Same groans when the morphine wore off. Medics moved between them without distinction, pressing fingers to pulses, adjusting dressings.

Captain Bradford checked Dieter’s chest twice a day, listening with a stethoscope, frowning thoughtfully, adjusting the drainage tube.

“Lung’s reinflating nicely,” he said one afternoon. “You’re going to make it, Hoffmann.”

Dieter stared at him. “You speak my name,” he said in halting English. “Not ‘Kraut.’ Not ‘enemy.’”

Bradford shrugged. “Easier than yelling ‘hey, you, collapsed lung.’”

The joke sat strangely on Dieter’s ears. Warm. Human.

Every evening, Sergeant Hayes appeared.

He never stayed long—fifteen, twenty minutes at most—but he came, dropping onto the stool by the bed with the controlled heaviness of someone whose body had forgotten what real rest felt like.

Sometimes he brought scraps for Blitz, who had taken to shadowing Hayes during the day when Dieter slept, then returning to the cot whenever Dieter stirred.

“Your English is pretty good,” Hayes said on the third evening, switching languages mid-sentence. “Where’d you learn?”

“School,” Dieter said. Talking hurt, but he wanted to. Needed to. “Before the war. We read…Hemingway. London.”

Hayes’s eyes lit for a second. “Jack London? Call of the Wild?”

“Yes,” Dieter said. “That one. Dog and man in the snow.”

“Good book,” Hayes said. “Hard book, but good.”

They sat in silence for a bit, the weight of the war pressing in around the edges.

Finally, Dieter asked the question that had been shredding his sleep.

“Sergeant Hayes,” he said carefully, searching for words. “Why did you save me? I am your enemy. I killed Americans.”

Hayes didn’t answer right away.

He leaned back, arms folded loosely over his chest, gaze drifting to the far wall and back.

“You want the honest answer?” he said at last.

“Yes.”

“That dog.”

Dieter blinked.

“The way he was begging us,” Hayes went on, nodding toward Blitz. “He grabbed my sleeve, tugged, wouldn’t take no for an answer. And when we found you, he lay down next to you like…like he’d die there if we didn’t do something.”

He rubbed a hand over his face.

“I couldn’t look into his eyes and walk away. Not after that. Made me think about my mutt back home. About loyalty. About what it says about a man that something that pure cares about him that much.”

He shrugged, almost embarrassed by his own honesty.

“Figured you couldn’t be all bad if a dog like that loved you,” he said.

Dieter swallowed hard. The ceiling blurred.

“They told us…” He had to stop and regroup. “They told us you torture prisoners. That Americans are savages. That you take…souvenirs.”

“Yeah,” Hayes said. “They told us Germans were all fanatics who’d fight to the last breath, shooting you in the back the second you turned around.”

He waved a hand, taking in the entire ward.

“Guess propaganda works best when the people on each side never get a chance to actually meet.”

He stood, easing the stool back. “Get some rest, Dieter. War’s almost over for you.”

“Sergeant,” Dieter called as he reached the door.

Hayes looked back.

“Thank you,” Dieter said. “For my life. For Blitz.”

Hayes just nodded. “Thank him,” he said, and stepped outside.

New prisoners arrived three days later.

They came in under guard, eyes wide, shoulders hunched as if expecting a blow. Some were wounded and went straight to cots. Others were whole but looked more broken than the men on stretchers.

“They will shoot us,” one whispered to another, voice shaking. “We will be tortured. Better to have died fighting.”

Dieter recognized the fear in their faces. He’d worn the same expression in his mind for months.

The words spilled out of him before he could think better of it.

“They won’t hurt you,” he called in German, pushing himself up on one elbow. His chest screamed. He didn’t care.

Heads turned.

“Americans saved my life,” Dieter said. “They give us food. Medicine. They treat our wounds.”

One older soldier snorted. “They have brainwashed you already,” he snapped. “Turned you into a puppet. You talk like them.”

Dieter gestured weakly at the ward. “Look around. German here. American there. Same bandages. Same blankets. They operate on us. Give us their morphine. Does this look like torture?”

Private Schmidt had been listening.

After the new prisoners were processed, he came over.

“You know what you just did?” Schmidt asked mildly.

“Told the truth,” Dieter said.

Schmidt smiled faintly. “The truth is what broke you free,” he said. “I left Germany in 1936. Saw which way the wind was blowing. But a lot of good people stayed. Believed what they were told because questioning was dangerous.”

He looked Dieter over, eyes kind.

“It takes courage to admit you were wrong,” he said. “You’ve got work to do with that courage.”

A week after his rescue, Dieter was walking.

Not far, and not without pain, but up and down the aisle between cots, Blitz pacing at his side, careful to match his speed.

Hayes came in one evening to find the Shepherd responding to English and German commands with equal enthusiasm.

“Sitz,” Dieter said. Blitz sat.

“Stay,” Hayes said. Blitz stayed.

“Smart dog,” Hayes observed. “Too smart for this damn war.”

“All of us are too good for this war,” Dieter said before he could stop himself.

Hayes looked at him, then smiled slowly. “Yeah,” he said. “You’re figuring it out.”

Dieter lowered himself back onto the cot, ribs complaining.

“What will happen to Blitz when I go to…P camp?” he asked. The word for POW in English still felt strange. “Can he come?”

Hayes’s face grew thoughtful. “Regulations say captured equipment—including animals—is property of the U.S. Army,” he said. “But Blitz isn’t equipment.”

He looked at the dog, at the way Blitz’s ears flicked at each of their voices.

“He’s…a soul,” Hayes said, stumbling a little over the word. “He chose to save you. That matters.”

“Will you take him?” Dieter asked.

The question hurt to ask, but it felt right. Blitz trusted Hayes now as much as he trusted Dieter. Maybe more. And what kind of life would a German dog have in a German city flattened and starving?

“When the war ends,” Dieter went on, “and you go home. He trusts you. He should…have a good life.”

“What about you?” Hayes countered. “What happens to you after this?”

Dieter looked down at his hands. They still shook sometimes.

“I don’t know if there will be an ‘after’ for Germany,” he said. “For Germans like me.”

He swallowed.

“Everything I believed in was a lie,” he said. “Everything I fought for was evil. How do I go home to that?”

Hayes sat again, the stool creaking.

“Listen to me,” he said quietly. “You were nineteen. You were lied to by people in power. That doesn’t make you evil, Dieter. It makes you a victim.”

“Victims become monsters,” Dieter whispered. “We did terrible things.”

“And you’re the one sitting here talking about it,” Hayes said. “That matters. The fact that you can see it now? That’s what counts.”

“Is it enough?” Dieter asked.

“It has to be,” Hayes said. “Otherwise there’s no hope for any of us.”

The day they moved Dieter to the POW camp, the air outside the aid station felt heavier than usual.

He stood in the yard, dressed in a clean but faded uniform with a red cross armband and a large “PW” chalked on his back. His ribs still hurt, but he could walk without feeling like the world tilted.

Hayes brought Blitz, freshly brushed, fur shining despite the war.

“I talked to my CO,” Hayes said. “I’m keeping him. When this is over, I’m taking him home to Iowa. Got a farm there. Fields, barns, kids to throw sticks. Dog heaven.”

Dieter knelt carefully. Pain flared, but he ignored it.

He wrapped his arms around Blitz’s neck and buried his face in the thick fur. The dog licked his cheek, tail wagging hard enough to shake his whole back half, utterly unaware of the human drama.

“Thank you,” Dieter whispered in German. “Für alles. For everything.”

He pulled back and looked up at Hayes.

“For everything,” he repeated. “For Blitz. For my life. For showing me what honor really means.”

Hayes reached down and hauled him to his feet with a firm grip.

“You survive this war, Dieter,” Hayes said. “You go home. You tell people what you learned. That’s how we make sure this doesn’t happen again.”

They shook hands.

German sniper. American sergeant. Enemies linked by a dog who refused to leave his injured master.

The war burned on for another eleven months. In POW camp, Dieter watched Germany collapse from a distance—bombed cities, surrender, trials. He heard stories in fragments, like bits of glass: camps liberated, numbers of dead too large to fit in his head.

He went home in September 1945 to a Munich that was rubble and dust.

Entire streets he’d grown up on were gone, replaced by piles of brick and twisted steel. The Glockenbach neighborhood had taken a bad hit. His family’s apartment building was a gaping hole.

He found his parents living in his uncle’s basement, three families sharing a space meant for coal and tools.

His father looked twenty years older, skin hanging loose, empty sleeve pinned neatly to his shirt.

“Dieter,” his father whispered when he saw him. “Mein Junge. We thought you were dead.”

“Almost was,” Dieter said.

He told them the whole story.

His mother wept quietly when he reached the part about Blitz bringing him water in the forest. His father wept openly when he described Hayes saving him.

“I tried to warn you,” his father said, voice rough. “Tried to tell you soldiers are just soldiers. It’s the men above them who twist everything.”

In 1947, with Germany slowly unfurling from the worst of the chaos, Dieter sat in a small room with a borrowed pen and a Red Cross form and wrote a letter.

He addressed it to: Sergeant Robert Hayes, Iowa, United States.

It felt ridiculous. America was enormous. Iowa was a blur on a map. But he wrote everything he could think of to help some clerk somewhere find the right farm.

Three months later, a letter came back.

The envelope was worn, corners soft. American stamp. His hands shook as he opened it.

Hayes’s handwriting was like his voice: firm, a little rough.

He wrote about the farm—cornfields, hogs, a white house that needed paint. About waking up some nights still hearing artillery. About how hard it was to learn to sleep without boots on.

And he wrote about Blitz.

“He’s happy here,” Hayes wrote. “Runs through the cornfields like he’s never known anything but freedom. Sleeps on the porch. Steals scraps from the kitchen. Sometimes, when he looks at me, I remember that forest in France, that moment I almost walked away. I’m grateful every day that I didn’t.

“That dog saved more than your life, Dieter. He reminded me why we were fighting. Not for territory or politics, but for the simple act of choosing compassion when cruelty would have been easier. He’s getting old now, but he’s loved. I hope that brings you some peace.”

It did.

Dieter kept that letter folded in his wallet until the day he died.

In 1950, Dieter walked through the doors of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität with a satchel full of borrowed books and a heart full of questions.

He studied history and education under professors who had survived exile, prison, or worse. Men and women who had hidden neighbors, lost colleagues, fought quietly from within.

One of them, an older professor with sad eyes and a sharp mind, pulled him aside after class one day.

“You have a responsibility,” the professor said. “You’ve seen both sides of the lie. You believed it. You broke free. You cannot keep that to yourself.”

Dieter nodded. “I know.”

He became a teacher.

He taught contemporary history and something no curriculum committee had a neat name for: critical thinking, conscience, doubt. His classroom never had enough chairs. Students sat on radiators, leaned against walls.

He started each semester the same way.

“I was you,” he’d tell them. “Young. Certain. Angry. I believed everything I was told. Every poster. Every speech. I was wrong about almost all of it.”

He told them about the propaganda posters, about sniper school, about the forest, about Blitz. About waking up in an American aid station and realizing the monsters he’d been taught to fear were just men, and often better men than the ones who’d sent him to kill them.

“Your job,” he’d say, “is never to stop asking why. Why am I being told this? Who benefits from my hate? What happens if I choose not to hate?”

His students called him “Herr Warum” — Mr. Why — behind his back.

He considered it the highest honor.

In 1961, a letter came from Iowa with bad news.

“Blitz passed peacefully this spring,” Hayes wrote. “Fourteen years old. That’s a good run for a shepherd. He died on the porch, in the sun, surrounded by my kids. I like to think he earned those extra years that night he refused to let you die.”

Dieter read the letter twice.

His wife Anna—whom he’d married in 1952, a widow who had lost her first husband on the Eastern Front—found him at the kitchen table, tears on his cheeks.

“That dog didn’t just save your life,” she said gently, resting a hand on his shoulder. “He saved your soul. And Hayes saved both of you.”

In 1967, Dieter stepped off a plane in Des Moines, Iowa, heart pounding harder than it had on any parachute jump.

America smelled different—corn and gasoline and coffee and something he couldn’t name.

Hayes stood at the end of the ramp, hair grayer, shoulders a little stooped, eyes exactly the same.

They recognized each other instantly.

“Sergeant,” Dieter said in English carefully.

“Dieter,” Hayes said, and then they were hugging, two middle-aged men clapping each other’s backs, laughing and blinking too fast.

The drive to the farm was all flat land and big sky. Hayes talked about crops and weather and his kids. Dieter watched the fields roll past, green and gold.

“This is where Blitz ran?” he asked.

“Every inch of it,” Hayes said, smiling. “Used to take off like a rocket every morning, then drag himself back at night like he’d fought the whole Wehrmacht.”

At the farm, Hayes led him around the house to a quiet corner under three oak trees.

There, a small stone marker sat in the grass.

BLITZ, it read. A GOOD DOG.

Dieter knelt, ignoring the twinge in his ribs that never quite went away.

He laid his hand on the warm stone.

In his mind, the years fell away. He saw Blitz’s face in the French forest, muddy and wild-eyed. Felt the dog’s weight across his chest in the freezing dark. Heard the whine when American boots appeared.

“Danke,” he whispered. “For dragging help. For not giving up.”

Hayes stood beside him, hand resting lightly on his shoulder.

“He never forgot you,” Hayes said. “Sometimes, near the end, he’d sit on the porch and stare east. I always figured he was thinking about you.”

They stayed there for a long time, two old soldiers, one old dog between them.

Dieter went home and kept teaching.

His students became teachers, journalists, judges, parents. They carried his story into classrooms he never saw, into courts, into conversations at kitchen tables.

They asked why a little more often.

In his final years, Dieter wrote a memoir.

He never tried to publish it. He bound the pages with string and handed copies to his children and his oldest students.

The last chapter was the forest in detail. The thunder. The tree. The dog. The Americans.

“I was trained to hate Americans,” he wrote. “To fear them. To believe they were less than human.

“But when I lay dying, it was an American who saved me. When I had nothing to offer in return, Americans gave me medicine, food, care. When my own comrades had written me off as dead, Americans carried me to safety.

“What does that tell you about the propaganda we believed? About the lies we were told? About the ease with which good people can be turned to evil, and the courage it takes to choose compassion over cruelty?

“And what does it tell you about a dog—just a simple, loyal dog—who refused to accept that his friend should die alone? Who bridged the gap between enemies with nothing but determination and love?”

He ended with the question he’d asked his students for decades:

“When have you looked at someone you were taught to hate and chosen instead to see a fellow human being? Someone who bleeds the same red, fears the same darkness, loves with the same desperate intensity?

“That is the question Blitz taught me to ask.

“That is the question that saved my soul.

“That is the question I hope you will carry with you forever.”

Dieter Hoffmann died in 1995, aged seventy.

His funeral in Munich was small by state standards and large by human ones. Three generations of students came, some with gray hair, some with ink on their fingers from the morning paper.

They told stories at the reception of “Herr Warum,” the teacher who made them argue with textbooks, who ruined propaganda for them forever, who made them see the people inside the uniforms in newsreels.

Among the flowers laid on his grave was a wreath that had crossed an ocean.

The card read:

For the friend our father never forgot, and the teacher who carried Blitz’s lesson forward.

With gratitude and love,

The Hayes family, Iowa, USA.

Half a world away, under the oaks in Iowa, Blitz’s stone grew soft-edged with weather, but the name stayed sharp.

If you stood quietly between those two graves—one in Munich, one in Iowa—and listened hard enough, you might have heard it:

The faint echo of a dog barking, urgent and insistent, refusing to let a man die alone.

Even in humanity’s darkest moments, there are choices.

There is the choice to believe the poster on the wall—or to believe the hand reaching down to lift you onto a stretcher.

The choice to walk away from a wounded enemy—or to follow a dog’s pleading eyes into the trees.

The choice to hold onto hate—or to let a German sniper’s dog refuse to leave his injured master until Americans saved him.

THE END

News

CH2 – How One Crewman’s “Mad” Rigging Let One B-17 Fly Home With Half Its Tail Blown Off

At 20,000 feet above the Tunisian desert, the tail of All-American started to walk away. Tail gunner Sam Sarpalus felt…

CH2 – The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men

The German officer’s boots were too clean for this part of France. He picked his way up the muddy slope…

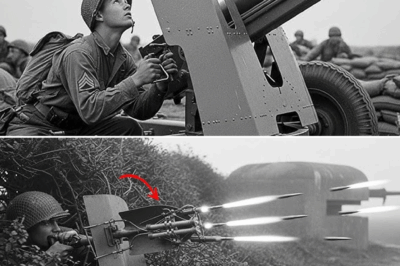

CH2 – This 19-Year-Old Was Manning His First AA Gun — And Accidentally Saved Two Battalions

The night wrapped itself around Bastogne like a fist. It was January 17th, 1945, 0320 hours, and the world, as…

CH2 – The German Boy Who Hid a Shot-Down American Pilot from the SS for 6 Weeks…

The SS officer’s boot stopped six inches from the boy’s nose. Fran Weber stood in the barn doorway with his…

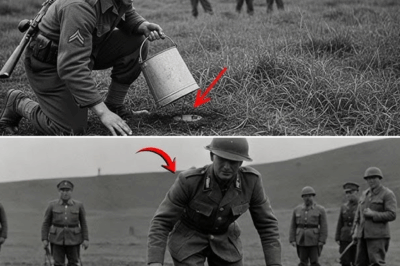

How One Private’s “Stupid” Bucket Trick Detected 40 German Mines — Without Setting One Off

The water off Omaha Beach ran red where it broke over the sandbars. Corporal James Mitchell felt it on his…

Germans Couldn’t Believe This “Invisible” Hunter — Until He Became Deadliest Night Ace

👻 The Mosquito Terror: How Two Men and a Radar Detector Broke the German Night Fighter Defense The Tactical Evolution…

End of content

No more pages to load