PART 1:

The Tuesday morning sun poured through the tall windows of Providence Municipal Court, turning the polished wooden floors into strips of gold.

Judge Frank Caprio adjusted his glasses, scanning the docket in front of him — the usual list of speeding violations, expired meters, and parking citations.

He’d seen a thousand mornings just like this one.

But that day, something in the air felt heavier — the kind of stillness that often arrived before a story worth remembering.

“Next case,” the clerk called. “Robert Martinez. Violation of handicap parking regulations. Citation number 47,829.”

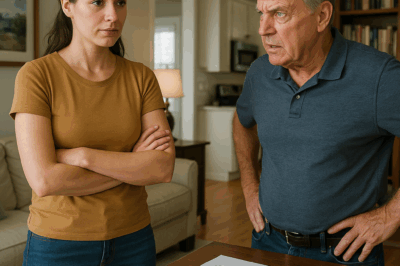

From the back of the courtroom, a man slowly rose.

Robert Martinez looked like life had tested him too many times and kept a few of the marks.

His graying hair was trimmed, his clothes pressed, but his gait was uneven. He gripped a cane in one hand, his right leg dragging slightly with each step.

Every move seemed to cost him something.

The murmurs in the gallery faded into silence as everyone watched this clearly disabled man approach the bench — a man accused of illegally using a handicap parking space.

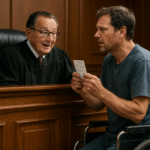

Even Judge Caprio’s eyebrows lifted slightly. “Mr. Martinez,” he said, his voice gentle but firm. “You’re here for a parking violation — specifically, illegal use of a handicap space. But before we go further, forgive me for the obvious question: you appear to have mobility issues. Don’t you qualify for a handicap permit?”

Robert stopped at the podium, his cane resting against the edge. His voice trembled slightly, but not from weakness — from months of held-back frustration.

“Your Honor, that’s exactly the problem. I’ve been trying to get a permit for eight months.”

The courtroom stilled.

Caprio leaned forward. “Eight months?”

“Yes, Your Honor. Eight months of forms, doctors, and waiting lists that lead nowhere.”

The judge motioned for him to continue. “Tell me what happened that day, Mr. Martinez.”

Robert took a slow breath, steadying himself.

“It was September 15th. Thursday. I had a doctor’s appointment downtown — my neurologist, Dr. Patricia Williams. I have multiple sclerosis. It’s been getting worse over the past two years.”

A ripple of empathy moved through the room. Even the court reporter’s fingers paused for a moment.

“I parked near the medical center,” Robert said. “Every regular space was full. But there were three open handicap spaces right by the entrance. I sat in my car for a while, wondering what to do. I don’t have a permit, but I can barely make it twenty yards some days. That day was bad — my left leg was numb, my balance off.”

He swallowed hard. “So I parked there. I put a note on the dashboard explaining that I was disabled and in the process of getting my permit. I listed my doctor’s name and number. I hoped whoever saw it would understand.”

Judge Caprio nodded slowly. “But when you came back…”

“There was a ticket. $150 fine. The note didn’t matter.”

Caprio leaned back in his chair, folding his hands thoughtfully. “Tell me something, Mr. Martinez. Why don’t you have a permit yet?”

Robert sighed, the kind of sigh that carried a lifetime of bureaucracy.

“I applied in January. The DMV told me I needed Form DMV-205, signed by my doctor. I did that. Then they said it was outdated — they’d switched to DMV-205A. So I went back. Dr. Williams filled out the new form. But then they wanted more paperwork — medical records, diagnostic proof, and a letter from my neurologist.”

“Which took how long?”

“Three weeks.”

“And when you turned it in?”

“They said my neurologist’s letter didn’t count because she wasn’t on the list of certified disability evaluators.”

The judge’s eyes darkened. “You’re telling me that even after two doctors confirmed your condition, the state still wanted another exam?”

“Yes, Your Honor. I had to see a state-approved evaluator. The earliest appointment was six weeks out.”

Caprio pinched the bridge of his nose. “Unbelievable.”

The spectators shifted, whispering quietly.

Robert continued, “I finally saw Dr. Kim, a state evaluator. He spent fifteen minutes with me — made me walk across the room, tap my knees with a hammer — and agreed I qualified. Then it took him two more weeks to send the report to the DMV.”

“And?”

“When I brought it in, the clerk said the report was missing a code number for their system. I had to go back to Dr. Kim’s office.”

Caprio’s mouth opened slightly, then closed again. “Let me guess. He was unavailable?”

“He was on vacation,” Robert said with a bitter smile. “For three weeks.”

There was a low murmur of disbelief from the courtroom.

“Mr. Martinez,” Caprio said, his tone growing sharper — not at him, but at what he represented. “So from January until July, you’d completed three doctor visits, multiple forms, and the state still hadn’t issued your permit?”

“That’s right.”

“And by then?”

“By then,” Robert said, “the original application form had expired. Six months validity. I had to start the entire process over again.”

An audible gasp came from somewhere behind the defense tables. Even the bailiff looked up from his clipboard.

Caprio leaned forward, elbows on the desk. “You had to start over.”

“Yes, Your Honor. Back to my doctor, back to my neurologist, back to the evaluator — only now the evaluator was booked until September.”

The judge shook his head slowly. “Eight months. You spent eight months trapped in paperwork while your condition worsened.”

“Yes, Your Honor.”

The courtroom had gone completely silent. The fluorescent lights buzzed faintly overhead.

“Tell me about the day of the citation,” Caprio said softly.

Robert’s voice broke slightly. “It was one of my bad days. My balance was gone. My leg wouldn’t cooperate. I was already late for my appointment and running out of energy. When I saw those handicap spaces, I knew I shouldn’t — but I also knew I couldn’t make it from the far end of the lot.”

“You left a note,” Caprio said.

“Yes, Your Honor. With my doctor’s information. I thought maybe someone would understand.”

“But they didn’t.”

Robert shook his head. “No.”

Caprio sat back in silence for a long moment. He tapped his gavel lightly against the bench — not in judgment, but in thought.

When he finally spoke, his voice was measured, heavy with empathy.

“Mr. Martinez, I’ve been on this bench for a long time. I’ve seen more parking tickets than I can count. But what you’ve described today is more than a violation. It’s a failure — not yours, but ours.”

Robert’s lips trembled. “Thank you, Your Honor.”

“I understand the law,” Caprio continued. “It says that parking in a handicap space without a permit is a violation. But the purpose of that law is to protect accessibility, not punish those who are already suffering.”

He leaned forward. “Technically, you broke the law. But morally?” He shook his head. “The law broke you.”

The courtroom held its breath.

Caprio turned to his clerk. “Is his medical documentation here?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” the clerk said, handing over a folder.

Caprio flipped through the papers, reading the dates, the doctor’s letters, the state forms stamped and restamped like relics of absurdity.

He looked back up at Robert. “Do you have your permit now?”

Robert nodded. “Finally, yes. Arrived last week. Eight months and seventeen days.”

Caprio smiled faintly. “Congratulations. Though I’d call it more survival than success.”

Laughter rippled softly through the courtroom — not mocking, but in shared disbelief.

The judge’s tone shifted. “Mr. Martinez, this court finds that you did, in fact, park in a handicap space without a permit. But it also finds that you did so out of necessity and in good faith. The system that should have supported you failed miserably.”

He picked up the ticket from his desk and tore it neatly in half.

“Citation dismissed.”

The courtroom erupted in applause before Caprio raised a hand to quiet them.

“But I’m not finished,” he said. “My clerk will assist me in drafting a formal letter to the Rhode Island Department of Motor Vehicles detailing your experience. No one with a legitimate disability should wait eight months for access they’re entitled to by law.”

Robert blinked hard, tears welling in his eyes. “Thank you, Your Honor. I don’t know what to say.”

“Just keep walking, Mr. Martinez,” Caprio said kindly. “That’s enough.”

As Robert turned to leave, dragging his leg and gripping his cane, the room stayed silent.

Not out of pity — but out of respect.

Caprio watched him go, then looked at the clerk.

“Please file that letter today,” he said quietly. “And get me the contact at the DMV director’s office. This one matters.”

“Yes, Your Honor.”

When the next case was called, the courtroom slowly returned to its rhythm — but the air had changed.

Every person in that room, from the bailiff to the teenager waiting for his speeding fine, knew they’d just witnessed something rare:

a reminder that justice, at its best, isn’t about punishment.

It’s about humanity.

And that morning, humanity had won.

Sure — here’s where the story expands beyond one morning in court.

This next part follows what happens when a small act of compassion starts to ripple through an entire system.

PART 2:

The day after the hearing, the Providence Municipal clerk’s office was busier than usual.

Reporters had already called twice asking for comment. Someone from the Providence Journal wanted to confirm if Judge Caprio had really torn up a ticket in open court.

Caprio didn’t like spectacle, but he also didn’t hide behind procedure.

He walked into his chambers, closed the door, and sat at his desk to write the letter he’d promised.

To the Director, Rhode Island Department of Motor Vehicles:

Yesterday, this court heard the case of Robert Martinez, citation #47,829, issued for parking in a handicapped space without a permit. The facts were clear; the law was not. Mr. Martinez suffers from multiple sclerosis, a progressive condition that limits his mobility. For eight months he attempted, in good faith, to obtain the required permit. He was met with delays, contradictions, and inefficiency. This is not simply administrative backlog; it is the systemic denial of accessibility to a disabled citizen.

I urge your department to review its policies and procedures regarding handicap permit applications. No citizen should spend the better part of a year proving a condition that is already documented by licensed physicians.

If the purpose of these permits is to assist, not punish, people like Mr. Martinez, then the process must reflect that purpose. I respectfully request a report on the department’s intended steps to prevent such failures in the future.

Respectfully,

Judge Frank Caprio

Providence Municipal Court

When he finished, he read the letter aloud, adjusted a few words, and signed it in blue ink.

Then he handed it to his clerk. “Send it certified. And copy the Attorney General’s office. If there’s a reform to be made, I want people who can make it reading this.”

Three days later, the phone started ringing.

A spokesperson from the DMV wanted to schedule a meeting.

A local news crew asked to film a short segment about the case for their community program.

Caprio wasn’t interested in publicity, but he agreed to the interview if they would focus on the issue, not on him.

When the segment aired that Sunday night, Robert Martinez was at home in his small apartment, watching from his recliner with his cane leaning against the wall beside him.

The footage showed his slow walk to the bench, his quiet voice as he explained his condition, and the judge’s final words: “The law broke you.”

Then the news anchor turned to the camera.

“Since this case, the DMV has confirmed an internal review of the state’s disability permit process.”

Robert exhaled, tears blurring the screen.

For the first time in years, someone had believed him without making him prove it twice.

A week later, a manila envelope arrived at the courthouse addressed simply to “The Judge Who Helped Me.”

Inside was a handwritten note:

Dear Judge Caprio,

I saw your letter on the news. I’m a veteran with a spinal injury. I’ve been waiting six months for my own permit. What Mr. Martinez went through — I’ve been living it too. Thank you for making someone listen.Sincerely,

Thomas Reynolds, Cranston, RI

Caprio read it twice, then set it beside a stack of others that began arriving that same week — from nurses, social workers, caregivers, and disabled residents across Rhode Island.

Each letter told a different version of the same story: long delays, lost forms, endless loops of reapplication.

“Looks like Robert Martinez wasn’t the only one,” his clerk said, sorting through the pile.

“No,” Caprio murmured. “He was just the one who walked through my courtroom first.”

Robert himself came back to the courthouse two weeks later — not for another ticket, but to say thank you.

He wore a dark jacket and carried his cane like it was part of him.

When he stepped up to the clerk’s window, people in line stepped aside.

Caprio happened to walk through the lobby at that moment.

“Mr. Martinez,” he said, smiling. “You didn’t have to come back.”

“I wanted to, Your Honor,” Robert said. “I just wanted you to know they called me.”

“The DMV?”

“Yes. A supervisor. She apologized — said they’re changing the policy. They’re adding a fast-track for medical re-evaluations and an online system so people don’t have to wait in person for every step.”

Caprio’s face lit up. “That’s good news.”

Robert nodded. “You made it happen.”

Caprio shook his head. “You did, Mr. Martinez. You told your story. All I did was listen.”

By mid-October, the Providence Journal ran an editorial praising the court’s compassion and demanding broader reform.

Local legislators took notice. Within months, a proposal was introduced at the State House to simplify disability certification for parking permits.

Caprio was invited to speak at a committee hearing, but he declined. Instead, he sent a written statement.

“Let the record show,” he wrote, “that the spirit of the law must always outrank the bureaucracy that enforces it.”

It became a line quoted in papers across the state.

For Robert Martinez, life was still hard.

Multiple sclerosis didn’t get easier.

But small things began to change.

He received a new parking placard in the mail — permanent, with an expiration date of five years instead of one.

He started volunteering with a local disability rights nonprofit, helping others navigate paperwork and appointments.

When asked why he did it, he said, “Because once someone believes your story, you start believing it too.”

Judge Caprio kept working the bench, one citation at a time.

A speeding teenager.

A single mother with unpaid fines.

A retiree confused about meter times.

But something in the room was different now.

People looked at him with a little more hope — like maybe the system wasn’t only about punishment after all.

One afternoon, after dismissing a minor case, Caprio looked out at the packed courtroom and said something that wasn’t on the record:

“Everyone in here has a story. If we forget that, we forget what justice is for.”

The following spring, a letter arrived from the governor’s office.

It contained a single page, embossed with the state seal.

Dear Judge Caprio,

We wish to inform you that, due to your correspondence and testimony, the Rhode Island DMV has implemented new procedures for disability permit applications. Average processing time has been reduced from 90 days to 15. Your advocacy directly impacted this reform.Respectfully,

Governor Elaine Russell

Caprio folded the letter carefully and placed it in a drawer in his chambers. He didn’t tell the press. He didn’t need to.

That evening, as he left the courthouse, he spotted Robert Martinez waiting by the steps.

Robert’s cane tapped softly against the stone.

“Judge,” Robert said, smiling. “Did you hear? They passed the reform.”

“I did,” Caprio said. “I think you’re the reason it passed.”

Robert chuckled. “Funny. I came here months ago feeling like a criminal. Now people stop me on the street to thank me.”

“They should,” Caprio said. “You gave a face to a problem.”

Robert hesitated. “Your Honor, can I ask something? Do you ever get tired of hearing all these cases? All the small stuff?”

Caprio looked out at the skyline glowing gold in the evening light. “There’s no small stuff when it’s somebody’s life.”

That night, the local news aired another story — not about bureaucracy this time, but about people.

The segment showed Robert helping another disabled veteran fill out a new online application.

A voice-over explained how his case had led to statewide change.

At the end of the clip, the reporter asked him, “Do you feel justice was served?”

Robert smiled faintly. “Yeah. Justice isn’t just what happens in court. It’s what happens after.”

From that day forward, Caprio kept a new sign on his bench.

Simple words, carved in wood:

Justice with Compassion.

He didn’t need to remind himself why he put it there.

He just wanted everyone else who stood before him to see it.

Got it — let’s keep going.

This next part takes the story further into what happens when compassion becomes a headline and real people start to push back.

PART 3:

By summer, the story had outgrown Providence.

What started as a quiet dismissal of a $150 ticket had turned into something else—a symbol.

Clips of Robert’s case from the local broadcast were being shared online, millions of views on social media under captions like “This is what justice should look like.”

For the first time in decades of municipal hearings, Judge Caprio’s courtroom had gone viral.

The phone at the clerk’s office rang constantly.

Producers from national news outlets wanted interviews.

Morning talk shows wanted Robert and the judge sitting side by side, talking about “compassion in the justice system.”

Caprio refused most of them.

“I’m not interested in being a celebrity judge,” he said. “I’m interested in making sure people like Robert don’t get buried by red tape.”

Robert, on the other hand, wasn’t sure what to do with the attention.

He’d never been on television before; now strangers stopped him in the grocery store to shake his hand.

They called him “the man who changed the system.”

He still walked with a cane. He still fought flare-ups. But for the first time in years, people saw him as more than his illness.

In late June, Caprio received a formal request from a Boston-based legal association inviting him to speak at their annual conference on “Restorative Justice and Public Trust.”

He almost declined—it wasn’t his style—but his law clerk, Hannah, insisted.

“Judge, you always tell people that justice has to listen. Maybe this time, people need to listen to you.”

He agreed.

The conference hall was filled with lawyers, clerks, and policy makers from all over New England. When Caprio stepped onto the stage, there was polite applause.

He didn’t bring slides or statistics. He just told Robert’s story.

When he finished, the room was silent for a long moment. Then, one by one, people stood up and applauded. Not the performative kind, but the kind that meant something.

A week later, the backlash began.

Anonymous op-eds appeared online accusing Caprio of “judicial overreach” and “playing politics with emotions.”

One radio host sneered, “Since when do judges decide law based on feelings?”

The DMV’s regional director sent an internal memo—leaked within hours—complaining that the new reforms were “a logistical nightmare” and that “certain high-profile cases had forced rushed policy changes.”

When a reporter read the quote to Caprio, he simply said, “If compassion is inconvenient, that’s a problem worth having.”

Robert felt the backlash too.

A few bloggers dug into his personal history—medical records, old jobs, even his divorce—and painted him as “a manipulative opportunist.”

He stopped reading the comments.

He focused on his volunteer work instead, helping disabled veterans navigate the new permit application system.

One morning, a woman named Sandra stopped him outside the disability center.

She was in her forties, her leg brace shining in the sun.

“Mr. Martinez,” she said softly, “I got my parking permit last week. Took two weeks. Not eight months. Because of you.”

He didn’t know what to say. So he just smiled and nodded.

By autumn, Judge Caprio’s chambers were receiving letters from as far away as California.

A high school civics teacher in Oregon wrote,

We watched Robert Martinez’s case in class. My students are talking about what fairness really means. Thank you for showing them that kindness belongs in courtrooms.

Caprio pinned that letter to his corkboard. He kept adding new ones until the wall looked like a patchwork of humanity—each note a story of someone who’d stopped feeling invisible.

But not everyone wanted to celebrate.

A month later, Caprio received a summons of his own—an official request to appear before the state judicial review board.

The complaint: “Inappropriate use of courtroom discretion and public advocacy on active legal policy.”

He smiled faintly when he read it.

“I must be doing something right,” he told Hannah.

The hearing was held in a gray conference room at the state house.

A panel of five judges sat behind a long table.

The senior member, Judge Eleanor Jameson, adjusted her glasses. “Judge Caprio, we appreciate your time. This inquiry is procedural, not punitive.”

“I understand,” he said.

She continued, “You dismissed a citation under extraordinary circumstances. You also corresponded directly with a state agency. Some have argued this exceeds your purview as a municipal judge.”

Caprio nodded. “That’s true. I did write that letter.”

“Why?”

“Because the man I saw that morning wasn’t just a defendant. He was a citizen being crushed by the weight of our process. I believed my duty extended to fixing the process that failed him.”

The panel was silent.

Judge Jameson leaned forward. “Do you believe the law should be guided by empathy?”

“I believe the law without empathy stops being justice,” Caprio said simply.

The board’s review concluded two weeks later with a unanimous decision:

No violation. Commendation for civic integrity.

A copy of the ruling was published quietly on the state website. But people noticed.

The same week, a national magazine ran a cover story titled “The Kind Judge: Can Compassion Reform the System?”

Caprio didn’t read it.

He was too busy preparing for court.

One rainy Tuesday, nearly a year after the original ticket, Robert Martinez returned to that same courtroom.

He wasn’t on the docket. He was there as a guest.

The case being heard that morning was painfully familiar:

A young woman with cerebral palsy had parked in a handicap space without a permit.

Her temporary tag had expired during a hospital stay, and she’d been fined.

When the judge asked if she had anything to say, she stammered, “I couldn’t walk that day, Your Honor.”

Caprio glanced at Robert in the front row, then back at the woman.

“I know someone who understands exactly what you’ve been through,” he said.

He gestured toward Robert. “Would you mind standing, Mr. Martinez?”

Robert rose slowly, cane in hand.

The courtroom murmured. Everyone recognized him from the news.

Caprio smiled gently. “This gentleman’s story changed the way we handle these cases in Rhode Island. And I’m not about to undo that progress.”

He turned back to the young woman.

“Case dismissed. And my clerk will help you file for a renewal before you leave the building.”

The room erupted in soft applause.

Robert’s eyes glistened.

Justice, full circle.

After court, Robert waited for the woman in the hallway.

She thanked him through tears.

He just shook his head. “Thank the judge. He listens.”

She smiled. “You gave him something worth hearing.”

That evening, Caprio found a small envelope on his desk.

Inside was a handwritten card:

*Your compassion reached further than you’ll ever know.

Anna and her daughter, Grace.*

He didn’t remember the names, until he realized—Grace was the young woman from that morning’s case.

He closed his office door, sat in the quiet, and smiled.

When asked years later what case he remembered most, Judge Caprio never hesitated.

“Robert Martinez,” he’d say.

“The man who reminded me that laws are just words until someone gives them a heart.”

PART 4:

It had been seven years since the morning Robert Martinez limped to the podium of Judge Caprio’s courtroom.

Seven years since the sound of a gavel turned into something much larger than a single ruling.

The world had moved on, as it always does, but the echo of that decision kept finding new places to land.

By 2027, Rhode Island’s new disability access law was in full effect.

Processing time for handicap parking permits averaged nine days.

Renewals could be handled online.

Medical certifications were recognized across state lines, removing the need for multiple evaluations.

The DMV director—no longer the same one who had complained about “inconvenient compassion”—kept a framed copy of Judge Caprio’s letter on her office wall.

At the bottom of it, she’d written in blue ink:

If compassion is inconvenient, fix the system, not the compassion.

At Roger Williams University School of Law, Professor Hannah Delgado—once Judge Caprio’s law clerk—stood before her class of future attorneys.

On the projector behind her was a photo of the old municipal courtroom.

“This,” she said, tapping the image, “is where justice met humanity.

Judge Caprio taught me that precedent doesn’t just live in law books—it lives in people.

Today we’re studying discretionary authority. Tomorrow, we’ll talk about moral courage.”

A hand went up in the back of the room.

“Professor Delgado, do you think it’s dangerous when judges let emotion guide rulings?”

Hannah smiled.

“Emotion isn’t the danger. Indifference is.”

Robert Martinez had become something no one, least of all he, expected: an advocate.

He worked part-time with the Rhode Island Disability Alliance, traveling between community centers, hospitals, and schools to speak about accessibility and reform.

The cane was still there, but so was a confidence that hadn’t existed before.

People listened when he spoke.

He wasn’t just “that guy from the viral video” anymore.

He was living proof that the system could change—if someone cared enough to push.

One day, a high school student named Ellie approached him after a talk.

She had cerebral palsy and was studying pre-law.

“You’re why I want to be a lawyer,” she said.

Robert smiled, a little embarrassed. “That’s a lot of pressure.”

“It’s not,” she said. “You already did the hard part.”

He carried that line with him for weeks.

The following spring, Robert received a formal invitation in the mail.

The City of Providence invites you to attend the dedication of the Caprio Center for Civic Justice.

He stared at the envelope for a long time, smiling.

It had been years since he’d seen the judge in person.

He’d followed the news—Caprio’s retirement, his ongoing work with local charities—but they hadn’t spoken since the final interview after the reforms passed.

The ceremony took place on a bright April morning.

The new building stood beside the courthouse where everything began.

Reporters, city officials, and former defendants filled the seats.

A large bronze plaque read:

In honor of Judge Frank Caprio — who reminded us that mercy is not the absence of justice, but its fulfillment.

When the applause quieted, the mayor took the podium.

“Before we invite Judge Caprio to speak,” she said, “we’d like to recognize the man whose story started this journey—Mr. Robert Martinez.”

The crowd turned as Robert rose slowly from his seat, leaning on his cane.

He made his way to the stage, each step a memory.

Caprio smiled as Robert approached.

They hadn’t aged the same—Caprio’s hair silver, his posture still proud; Robert a little more bent, but steady.

They shook hands like old friends.

“Mr. Martinez,” Caprio said into the microphone, “when you stood before me that morning, I thought I was just hearing another case.

I had no idea I was meeting a teacher.”

Robert chuckled. “You were the teacher, Judge.”

Caprio shook his head. “No. You taught me that justice without empathy is just paperwork.”

When it was Robert’s turn to speak, he looked out at the crowd.

“I used to think justice was something handed down from people like Judge Caprio,” he began.

“But I’ve learned that it’s something we build together—every time we choose to care instead of look away.

If I’ve learned anything from this journey, it’s that one voice can start a conversation, but compassion keeps it going.”

The audience stood in applause.

Caprio’s eyes glistened.

After the event, Caprio invited Robert into his office—smaller now, more personal.

Books lined the walls, photos of family and decades of service on every shelf.

On his desk sat a framed letter, faded but preserved.

Robert recognized it instantly.

“The DMV letter,” he said.

Caprio nodded. “The one that started all this. I keep it as a reminder that even small acts matter.”

Robert smiled. “You really think one letter can change the world?”

“No,” Caprio said. “But it can change a life. And that’s how the world changes—one life at a time.”

They sat in silence for a moment, two men who had walked through different storms to arrive at the same calm.

That fall, the Caprio Center launched a scholarship in Robert’s name for law students dedicated to disability rights.

Ellie—the girl who’d told him she wanted to be a lawyer—was its first recipient.

When she received her certificate, she sent Robert a short note:

You made it possible for people like me to believe the law has a heart.

Robert framed it and hung it beside his front door.

One evening, years later, a local TV segment aired a clip titled “Where Are They Now?”

It showed Robert, now in his sixties, helping an elderly woman into her car in a hospital parking lot.

The camera zoomed in on the sign above the space:

RESERVED FOR DISABLED PERMIT HOLDERS.

The narrator’s voice said, “Because of Robert Martinez and Judge Frank Caprio, these spaces—and the dignity they represent—exist without barriers.”

Robert didn’t see the segment.

He was too busy loading the woman’s walker into her trunk.

As the sun set over Providence, a new day of cases began in the same courthouse where it all started.

A young judge took the bench beneath the same carved words: Municipal Court of Providence.

She was nervous but steady.

Before calling the first case, she glanced at a small plaque mounted beside her seat.

It read:

Justice with Compassion — In memory of Judge Frank Caprio.

She smiled softly. “Let’s begin,” she said.

And somewhere across town, Robert Martinez sat on his porch, cane resting beside him, watching the sunset bleed across the sky.

His phone buzzed—a message from Ellie.

A photo of her in a courtroom, standing before a judge, wearing a lawyer’s pin.

We did it, Mr. Martinez.

He typed back, his hands shaking slightly:

You did it. Keep going.

Then he put the phone down, leaned back, and closed his eyes.

He wasn’t just the man from the video anymore.

He was part of the reason the system had a soul again.

THE END

News

CH2 – At Dinner, My Fiancée’s Friends Demanded I “Prove My Worth” By Paying Their $800 Tab…

Part 1 I’ve spent my career making sure things get from Point A to Point B efficiently, but no one…

CH2 – They Said the Alpha King’s Bride Was Ugly — Until He Lifted Her Veil and Stood Frozen…

Part 1 The scent of burnt sage and bitter herbs filled the narrow cabin, swirling through the air like a…

CH2 – MY SON CAME HOME FROM SCHOOL, LOOKING TERRIFIED. “DADDY, TEACHER SAID I SHOULD NEVER TELL…”

PART 1: The day started like any other—coffee half-drunk, morning news humming in the background, the faint smell of wet…

CH2 – When I Came Home from NATO Duty, I Didn’t Expect My Own Father to Drag Me Into Court…

Part 1 They say when you come home from war, you don’t just unpack your bags—you unpack everything you carried…

CH2 – “You’re Not My Husband or My Owner,” My Fiancée Said After Taking the Waiter’s Number. I Nodded and Left…

Part 1 I used to think love could survive anything. Distance, doubt, even pride. I was wrong. My name’s Victor…

CH2 – My DAD Tried To STEAL My Daughter’s COLLEGE FUND. I Set A Boundary. He’s Still Mad…

Part One: The night smelled like cinnamon and cheap victory. Mom’s store-bought pies were sweating under their fake “homemade” crusts….

End of content

No more pages to load