Part 1

The seventieth birthday cake was a hazard the insurance adjusters would have sighed about—seventy thin sticks of fire flickering in a crescent, smoke curling like a warning under Mom’s kitchen ceiling. Phone flashes burst, and the crowd squeezed tighter around her like she was a local celebrity. Aunt Diane, beaming and commandingly off-key, launched into a louder rendition of “Happy Birthday,” harmonies sliding off like oil on water. Next to Mom stood my brother, Derek—broad-shouldered, clean-shaven, cufflinks glinting—his arm loosely draped around his wife, Amanda, who favored the camera with an angle she’d rehearsed.

I hovered in the doorway with a glass of sparkling cider. I’d been hovering for three years—on the edges of rooms, on the edges of conversations, on the edges of a life I could neither explain nor escape.

“Sarah, get in the photo!” Aunt Diane called without really looking at me, like a teacher tossing a participation point at the quiet kid. No one shifted to make room. No one moved their ankles to open a lane.

“I’m good here,” I said, the words swallowed by the choir of “toooooo you.”

The song ended. Mom leaned to blow, and Derek performed his favorite trick: make himself the hero. He waved air with a magazine, he kissed Mom’s cheek for the camera, he tapped a fork to a glass and declared, “Speech!”

“I just want all my babies together,” Mom said, clutching her pearls like she hadn’t practiced it in the bathroom mirror. “Family is everything.”

Family is everything, and secrets are the solvent.

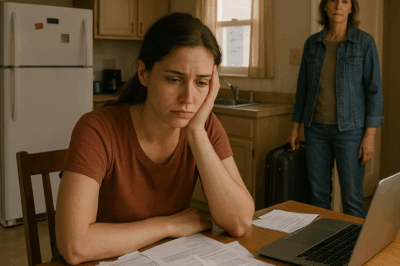

I took a sip of cider I didn’t want. The bubbles scratched my tongue. Three years of birthdays missed, of Thanksgivings with an empty chair, of Christmases where my name was no more than a line on a card—they had stacked like unfiled paperwork on my back. It wasn’t a breakdown. It wasn’t some mysterious vanishing act. It was the Witness Security Program, but I couldn’t say the acronym out loud. I couldn’t say anything. My life had been redacted in black bars and sealed envelopes.

I’d been a senior accountant at Morrison & Price, a mid-sized firm with bland carpet and politely competitive coffee mugs. The day my life detonated, I was reconciling a client’s cash receipts—one of those glossy “legitimate” operations downtown that always paid invoices by wire at 4:58 p.m. I noticed a pattern in the fractions, an elegant repeating decimal never landing quite right. Money laundering doesn’t always wear a ski mask. Sometimes it slips around a ledger in silk gloves.

I reported it. I testified. The U.S. Attorney’s Office called me “essential.” The marshals called me “relocatable.” I moved. My phone became a monitored instrument. The three-bedroom colonial I’d bought in a Philadelphia neighborhood near Rittenhouse—my miracle at twenty-six, my proof I could build a world with spreadsheets and grit—was locked down as a protected asset. No visitors without escort. No contractors without clearance. No sale, no transfer, no keys under the mat like a normal person’s life.

My family knew none of this. To them, I’d left. To them, the house was a ghost. To them, I’d turned my back on blood.

From the “Happy Birthday” scrum, Derek caught my eye with a captain’s smirk. His voice rose as the party slid into coffee. “So, Sarah,” he announced, theatrically stretching the syllables like a judge calling a case, “we need to talk about your property situation.”

“Pi—what?” I said, then corrected myself, “My what?”

“Your house.” He said the word like other men say “your garbage.” “The one you abandoned. The one sitting empty for three years in a good neighborhood. The one choking on back taxes.”

“I didn’t abandon—” I started.

“—your mysterious job,” Amanda sang in a brittle soprano. “The one that’s so important you can’t be bothered to come home.”

“I’m here now,” I said, softer than I meant to.

“After three Christmases,” Derek clipped. “Two Thanksgivings. Mom’s last birthday. You waltz in for one party and think that’s a refill of goodwill?”

Dad set his coffee down a little too hard. “Derek, what’s this really about?”

“I’m getting to it,” he said, and pulled out his phone like a magician producing a dove. He tapped, found his screen, then held it up to me: a real estate listing, the paint on my porch brighter than it ever was in life. SOLD, the banner screamed. $875,000. My living room captured in golden-hour light. My kitchen counters cleared of their old toaster, staged with lemons I never bought.

My heart did something quiet and dangerous. “You sold my house,” I said. Not a question. A diagnosis.

“I handled your abandoned property,” he corrected, savoring the syllables. “You weren’t paying the taxes. The HOA was threatening liens. Somebody had to act like an adult.”

“How,” I asked calmly, because calm is a tool, “did you sell a house you don’t own?”

“Power of attorney,” Amanda chimed, pleased to be needed. “He got it notarized. Two years ago, when you were barely functional.”

A hot, clean certainty slid through me. “I never gave you power of attorney.”

“Sure you did.” Derek swiped. A document sprang up, stamped, signed, a notary seal puckered like a kiss of doom. My signature appeared there—my tidy accountant’s loop—but it was wrong in the way a perfectly mimicked accent is wrong. The cross on the “t” too assertive. The “S” not quite right where muscle memory should curl.

“That’s not my signature,” I said.

“Oh, come on,” Derek rolled his eyes. “Classic Sarah. Excuses. You were a mess, you don’t even remember what you signed. I sold it last week. Closed. Clean. You should be thanking me.”

“Where’s the money?” I asked.

“What money?” he said, stone-stupid denial.

“The $875,000.”

“I used it to pay off your debts,” he said, like a martyr reading his citations. “Taxes. HOA. Landscaping. The legal fees I incurred handling your mess. And after everything Mom and Dad did for you, I thought a little compensation was appropriate.”

“How much?” I asked.

“Two hundred,” Amanda said crisply, proud to have memorized a number. “Which is more than fair, considering.”

“And the rest?”

“Expenses,” he said with a shrug that told me the word had been a down comforter for weeks. “About fifty grand left.” He pulled a white envelope from his jacket and tossed it on the coffee table like a goody bag. “A gift, for finally showing up.”

I didn’t pick it up. I could feel Aunt Diane’s glare warming my cheek; Uncle Mike’s mouth had already formed the syllables of ungrateful.

“You forged my signature,” I said.

The room erupted. “Don’t you dare,” Mom snapped, tears already loaded like ammunition. “Don’t you start accusing your brother. He has been here. He has been present.”

“You were gone,” Aunt Diane added, indexing her grievances with a raised finger. “You won’t say where you live, what you do. You flit in and out like a ghost. Derek did what needed doing.”

“The house wasn’t abandoned,” I said. “It was being maintained. The taxes were paid. The mortgage was current.”

“By who?” Derek challenged. “Because I drove by a dozen times and it looked like a funeral home for roaches.”

“Empty doesn’t mean abandoned,” I said.

“It means you weren’t there,” Amanda snapped. “And when you’re not there, the world moves on.”

I felt my phone buzz in my pocket. Three times. Four. The vibration was not random. The U.S. Marshals Service watches more than threats; it watches stress. The “fitness watch” on my wrist did two jobs, and it had just filed a report.

Around me, the family tribunal nodded and clucked. “Finally making sense?” Derek asked, tipping an imaginary hat. “Take the fifty. Be grateful. We did you a favor.”

My phone buzzed again. The doorbell rang.

“I’ll get it,” Emma—mid-twenties, sweet, a witness to a war she didn’t start—said, and padded down the hall. We heard the door open, a gust of October, and a man’s voice professional enough to chill a room.

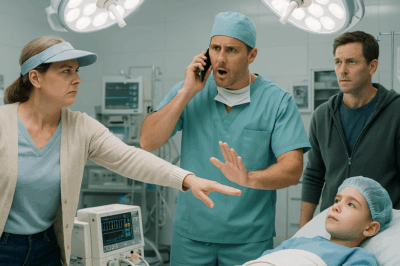

“U.S. Marshals Service. We need to speak with Sarah Mitchell immediately.”

The living room froze as if God had pressed pause. Emma reappeared, color drained. “Sarah,” she said. “There are… federal marshals here.”

“I’ll handle it,” I said, and stood.

Two men stepped into Mom’s living room that smelled like frosting and coffee and a lifetime of television. Deputy U.S. Marshal James Walsh led; his suit was federal-issue, his eyes not. He’d seen me bawl on a government couch the day they moved me; he’d watched me rebuild a life with receipts and routines. Behind him was a younger marshal, Chin, whose hand rested near his hip in a way that had no patience for nuance.

“Ms. Mitchell,” Walsh said, voice steady, eyes quietly concerned. “We need to speak with you now.”

“What is happening?” Dad demanded, half-rising.

“Sir, please remain seated,” Chin said without raising his voice. It still felt like a wall.

Walsh didn’t take his eyes off me. “Our property monitoring system flagged an attempted sale of your Philadelphia residence, recorded last week. Can you explain?”

“I didn’t authorize any sale,” I said, loud enough for the room, clear enough for the record. “I haven’t been to that property in three years. Per program protocols.”

“Program?” Derek blurted, going the color of copy paper. “What… what program?”

Walsh turned slowly. “And you are?”

“Her brother,” Derek said. “I sold the house. She abandoned it. I had power of attorney. The sale was completely legitimate.”

Walsh’s jaw flexed once. “Deputy Chin, call it in. Possible federal property fraud, witness security violation, and unauthorized access to protected assets.”

“Whoa—what the hell is going on?” Derek’s voice cracked.

Walsh faced him fully now, all the friendliness slid off and put in a drawer. “Mr. Mitchell, the property you sold is a federally protected asset held under the authority of the U.S. Marshals Service in connection with an ongoing federal prosecution. It cannot be sold, transferred, accessed, or discussed without authorization. The act you committed is not only void—it is a federal crime.”

Mom began to cry in earnest. Aunt Diane put a hand over her mouth like she was in a daytime soap. Uncle Mike muttered overreach.

“You never told us,” Derek said—accusation dressed as defense.

“She couldn’t tell you,” Walsh said. “That is the point of classified. And forging a power of attorney doesn’t become legal because you didn’t know the statute.” He held out a hand. “Show me the document.”

Derek fumbled with his phone, palms sweating. He pulled up the JPEG and thrust it out. Walsh looked for three seconds. “Fraudulent,” he said. “Ms. Mitchell was in federal protective custody on the date this purports to be notarized—Oregon, to be exact. The notary stamp is counterfeit. The signature is forged. And even if it weren’t, witnesses cannot assign authority over protected assets.”

“How was I supposed to know?” Derek shouted. “No one tells us anything!”

I faced him. “You didn’t care. You saw a house you didn’t earn and money you wanted.”

“We’re family,” he said, as if the word were a multi-tool that could pry open any locked door.

“Family doesn’t counterfeit,” I said.

“Ms. Mitchell,” Chin said, phone pressed to his ear, “command confirms. Task force is aware. Funds will be frozen. Title clouded. They’re dispatching a recovery team.”

Amanda began to cry, mascara drawing two black commas down her cheeks. “What will happen to Derek?” she asked, the you monsters silent but screaming.

“That depends,” Walsh said, and looked at me. “Ms. Mitchell, do you wish to press charges?”

The room stopped breathing. Every eye turned to me like I had a lever in my hand.

Derek, who had called me weak since third grade, stared with a boy’s panic in a man’s suit. He shook his head minutely—no, no, don’t—then pulled his mouth into the smirk he’d raised me with. “You wouldn’t,” he said, trialing bravado like a parachute he wasn’t sure would open. “You can’t… you can’t do that to me.”

I thought of the ledger entries that didn’t add, the long instructions whispered in fluorescent rooms, the morning I signed away my routines and handed over the keys to the life I’d built because justice needed a witness more than a woman needed comfort. I thought of a corpse that could’ve been me if someone had found a loose thread to pull. I thought of my house, staged with someone else’s lemons and someone else’s lie.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

Mom let out a sound like fabric tearing. “He’s your brother,” she gasped.

“He’s a criminal,” I said. “And he almost got me killed.”

Walsh stepped forward, his voice shifting into the rhythm that turns a life into a case. “Derek Mitchell, you are under arrest for fraud, forgery, and obstruction of justice relating to a protected federal witness asset. You have the right to remain silent…”

Chaos is never cinematic when it’s yours. It’s just loud and close. Amanda shrieked while grabbing his sleeve; Mom said no like it could become a spell if she said it enough times; Dad called me heartless like an old habit. Chin maneuvered, practiced and precise, and the cuffs clicked like a period, not an exclamation.

I stood very still. Somewhere in another room, a video of Mom’s cake burned thirteen seconds too long and hit a million views on an aunt’s Facebook. In our room, my brother was a defendant.

“Ms. Mitchell,” Chin said, the gentleness of professionals who deal in emergencies, “we need to move you. This incident could compromise standing protocols.”

“I understand,” I said.

Mom lunged forward and grabbed my wrist. “Don’t do this,” she pleaded, as if asking me not to touch a hot stove. “Don’t take your brother away.”

“I’m not taking him anywhere,” I said, and freed my wrist. “Consequences are.”

“You’re destroying this family,” Dad spat, like the judge he wasn’t.

“No,” I said, and looked at Derek as Walsh guided him toward the door. “He did.”

We stepped out onto the porch into an October that smelled like cinnamon and police plastic. The neighborhood watched through blinds. A neighbor’s dog barked into a story they would tell at dinner. You’ll never guess.

In the back of the government SUV, Walsh turned in his seat. “You okay?”

“I’m fine,” I said.

“That was your brother,” he said, not as a reproach but as a footnote.

“I know,” I said.

“Media will make hay,” he warned. “It won’t affect the prosecution, but it will be… noisy.”

“It’s been noisy for three years,” I said.

He smiled, a brief human thing. “Fair point.” He checked his watch. “We’ll stage you in Delaware tonight.”

We drove through a city that didn’t know my name, past a dozen homes that housed their own unspeakable catastrophes. The safe house in Delaware was a beige townhouse that had been painted so many times the walls felt like a stack of documents. Chin cleared the rooms and briefed the protocols. Walsh stood at the laminate counter, reviewing an email on his phone.

“Your brother will likely plead out,” he said. “Evidence is clean. The AUSA is furious. He’ll do time.”

“How much?” I asked.

“Two to five, depending on the judge,” Walsh said. “Restitution. Supervision. The buyers will be made whole. Title restored. Your house remains protected.”

I nodded. “Okay.”

“For what it’s worth,” Walsh said softly—man to woman now, not marshal to witness—“you did the right thing.”

I looked past him to a window that reflected a woman I recognized again. “It wasn’t the easy thing.”

“Right things rarely are,” he said, and his phone chimed again, and the world rolled forward.

Three hours later, the local news found its headline: FEDERAL WITNESS’S BROTHER ARRESTED FOR FRAUD — $875K HOUSE SALE VOIDS. By morning, Dad had given a quote to a sympathetic reporter about ungrateful daughters, and Aunt Diane had posted a prayer hands emoji over the words FAMILY FIRST.

I ate a government-provided granola bar and stared at a government-provided wall and waited for the trial I’d been living inside to reach a courtroom I could speak in without code.

Somewhere in Philadelphia, in a house I hadn’t seen for three years, my porch light—on a smart timer the Marshals controlled—clicked on. The steps glowed the same soft yellow as the day I signed the deed, twenty-six and invincible and not yet a target in a case whose name I can’t write here.

I breathed. I slept. In the morning, I began again.

Part 2

The safe house walls were the color of bureaucracy—off-white with the shine of paint applied in a hurry. The door hinges whispered when they moved, the HVAC hummed with the commitment of a government line item, and the blinds were the kind that clipped shut with a sound you couldn’t mistake for anything in the wild. Deluxe, in the way precooked airline meals were once called deluxe.

Chin swept the townhome the way he always swept a new space—methodical, laminated, his attention like a laser level. He checked returns in doorjambs, found a loose baseboard nail with a thumb, and wrote it on a yellow 3×5 card he slid beneath the toaster. Walsh set my temporary phone on the counter, then leaned on his knuckles like a man who knew the exact weight of the corner he was carrying.

“Today is triage,” he said. “Tomorrow is cleanup.”

I nodded and poured water into a kettle. My hands shook a little, but not from fear—adrenaline has a shelf life. The noise at Mom’s house was already a story that didn’t belong to me. The one that did was here: the soft butter knife, the dented saucepan, the laminated protocol binder on the table.

Walsh slid me a printed summary, stapled at the top: Property Incident — Mitchell, S. (Protected Asset). I skimmed. FUND FREEZE: Initiated. TITLE CLOUD: Initiated. RETRIEVAL: Pending buyer cooperation. NOTIFY: AUSA/Judicial.

He took out his phone and hit speaker. “We’re calling the AUSA,” he said. “You’ll want to hear the plan.”

The Assistant U.S. Attorney was a woman named Koh, all steel in a silk blouse. Her voice came through the little speaker like a string pulled taut.

“I’ve already contacted Title,” she said. “They’ve frozen disbursement and flagged the file. Proceeds are sitting two layers deep in escrow. We’re filing an emergency order to void the recording with the county.”

“What about the buyers?” Walsh asked.

“They’ll be made whole,” Koh said. “But they’re not going to enjoy the next forty-eight hours.”

“Who are they?” I asked.

“A pediatrician and a high school physics teacher,” Koh said. “They thought they were upgrading for a baby. They used a buyer’s agent with too much confidence and a title office with not enough imagination. They’ll be angry. They’ll be loud. You will not engage.”

“Understood,” I said, and meant it, mostly.

“And Ms. Mitchell,” Koh added, a shift in her tone that suggested she’d scanned my file in detail, “I’m sorry your family is a public mess. It complicates things. It does not compromise them.”

“What about my family’s mess has ever been quiet?” I said, dry enough to make Walsh glance at me with a flicker of a grin.

“We’ll arraign your brother on the initial charges tomorrow,” Koh went on. “The judge on duty this week is procedural to a fault. He’ll hold him. If Defense is smart, they’ll talk deal before lunch.”

“What’s the range?” Walsh asked.

“Two to five, depending on acceptance of responsibility and whether we tack on aggravated identity theft,” Koh said. “He forged a notary seal across state lines and touched a protected witness asset. I could make a meal of that.”

I said nothing. I was public property for a living now; my opinions were privileged only in my head.

“We’ll brief at 0700,” Koh finished. “Get her settled, Jim.”

“Copy,” Walsh said, and the call clicked dead.

He looked at me, weighing whether to offer the kind of consolation he was bad at or the kind of clarity he excelled in. He chose the latter.

“You’ve been through worse,” he said simply.

“I keep telling myself that,” I said.

He tapped the protocol binder. “Door code changes every twelve hours,” he said. “No porch lights unless we call it. Shower curtain stays closed. Stagger your blinds. This bathroom fan rattles—Chin will fix it.”

“Already did,” Chin said from the hall, not looking up from the outlet he was tightening. He pocketed the faceplate screw and added another note to the toaster card.

“Food drops are Tuesdays and Fridays,” Walsh said. “Don’t DoorDash. Don’t Amazon anything big. Pay cash. Keep the TV off unless you want to see your name in a font that doesn’t suit you.”

I turned on the kettle. It shivered as it warmed. “How’s he doing?” I asked, meaning Derek.

Walsh’s face didn’t move much. “He’ll look worse before he looks better.”

“Will he call me?” I asked.

“He can,” Walsh said. “He won’t. Not yet.”

I made tea. It tasted like carpet. I held the mug anyway.

The morning news opened with drone footage of the Philadelphia rowhouses along my old block—somber piano under a B-roll of brick that had survived worse. A chirpy anchor with a sympathetic eyebrow delivered the copy.

“—in a shocking twist, sources say the homeowner’s sibling executed the sale using fraudulent documents while the homeowner was under federal protection as a witness in a major money-laundering investigation—”

They cycled through the greatest hits: a blurred photo of me from five Christmases ago, Derek with his varsity grin from a charity 5K, our house with a SOLD banner that had aged a decade in a day.

Mom appeared on a local station in a cardigan that had been on our couch for twenty years. She clutched a tissue like she was auditioning for a role she had been playing my entire life. “We didn’t know,” she said, voice shaking on cue. “We would never put Sarah at risk. Derek was just trying to keep the neighborhood from turning on us.”

Aunt Diane posted a selfie prayer, head bowed under the words GOD GRANT US STRENGTH and three hundred comments that were alternately crucifix emojis and snake emojis, depending on which side of the family’s mythology you subscribed to. Someone started a GoFundMe for Derek’s legal defense called Keep A Good Man Free with a goal of $50,000 and a photo of him helping Mom carry groceries in 2016.

I turned the TV off. The room felt smaller without the phantom square of blue light.

Walsh arrived at 0615 with coffee so strong it might’ve melted an insecurity. We drove to the federal courthouse through a tunnel of October light and the hiss of tires on damp ramps. I went in the witness entrance with a badge that wasn’t my driver’s license but worked more often. Walsh walked me past detectors with a nod the guards knew, then tucked me in a small windowless room where public truth gets typed and private truth gets debated.

Koh came in with a tablet and the posture of a woman who breaks her heels and keeps walking anyway. Her suit was navy. Her eyes were focus and caffeine. She set a file in front of me. US v. Mitchell.

“You won’t need to say anything today,” she said. “But you should hear what’s said.”

“I’m good at hearing what people don’t say,” I said.

“I know,” she said. “That’s why you’re here.”

We watched the arraignment on a wall-mounted monitor—a courtroom in a high school geometry problem: lines, angles, rectangles, a judge whose expression had probably been carved by a sculptor named Procedure. Derek stood in a suit he hadn’t expected to need on a Wednesday, jaw clenched, wrists unadorned now that the cuffs had come off. Amanda sat behind him, mascara recalibrated, posture ramrod with grievance.

The prosecutor of record for the hearing—an associate from Koh’s team with shoulders that said he still played defense in a rec league—read the charges. Fraud. Forgery. Obstruction related to a protected federal witness asset. The clerk asked the questions that begin every federal chapter. Derek’s answers were clipped. Yes. Yes. Yes. Not guilty.

Defense counsel was a man I recognized from billboards on I-95—Have You Been Wronged? Call Sutter & Sutter. He attempted to make the case that this was a family dispute inflated by federal overreach, an issue of technicalities, not intent.

Koh’s associate politely eviscerated him with phrases that had case law tucked into them like razors: mens rea is not an element there, strict liability on the protection statute, the notary seal is counterfeit on its face, the protected asset registry controls.

The judge set bond high enough to feel like a decision but not high enough to inflame the caricature of bias. The conditions were the usual: surrender passport, no contact with the witness, stay at your address, check in with Pretrial Services. Amanda squeezed Derek’s arm; he didn’t turn.

“Counsel,” the judge said to both tables, “I expect plea talks to be substantive. We’re not going to waste the court’s time pretending this didn’t happen in a way the statute contemplates.”

He rapped his gavel like punctuation and left.

Koh exhaled. “He’ll plead,” she said, and slid the tablet into her bag. “You okay?”

“I will be,” I said.

“Good,” she said. “We need you again in four weeks. Pretrial conference on the big case. You’ll be under seal. We’ve filed to keep your new incident out of that courtroom, and the judge will grant it.”

“Because it’s prejudicial?” I asked.

“Because it’s irrelevant,” she corrected. “And because I said so.”

Outside, Walsh led me through a corridor that smelled like copier heat and coffee. We cut through a hallway no one uses unless they work there, and he held a door with his boot while I stepped into daylight.

“Eat something,” he advised. “Everything feels worse on an empty stomach.”

We found eggs at a counter where the man had regretted his small business loan three days after signing. Walsh didn’t speak until I’d finished most of mine.

“You want me to tell you what your brother is thinking right now?” he asked.

“No,” I said.

He ate a forkful. “He’s thinking he didn’t know,” he said anyway. “He’s thinking this is unfair. He’s thinking you did this to him.”

“He did this to himself,” I said.

Walsh nodded as if we were reciting the day’s weather.

“That doesn’t mean he’ll ever believe it,” he said. “Believe me when I tell you that the thing you owe yourself is not convincing him.”

“I know,” I said, and set my fork down. “I keep wanting to pay debts I don’t owe.”

He smiled, maybe, in a way that didn’t involve his mouth. “Then stop tipping,” he said.

The buyers’ agent emailed the AUSA a letter that might’ve been reasonable if it hadn’t been addressed to Whom It May Concern and cc’d to a reporter. Our clients are devastated. They took time off work to sign. They have nursery furniture in a storage unit and a baby due in December. How could this happen?

Koh drafted a reply that read like a bridge over burning grass: We regret the disruption. The government will ensure your clients are made whole. We recommend their counsel advise them to cease media statements so as not to complicate return of funds. She hit send, then turned to me.

“You don’t speak to them,” she said.

“I won’t,” I said. “I know that this isn’t my fire to put out.”

“It’s no one’s fire to put out,” she said. “It’s a controlled burn.”

The title company’s general counsel—old, tired, genuinely chastened—dialed into a conference call and said it in plain English: “We should’ve flagged the protected asset registry. We didn’t. We’ll eat our fees. We’ll eat a lot of crow.”

“Good,” Koh said. “Make sure your escrow officer understands she works for the word ‘fiduciary,’ not for likes.”

The county recorder’s office moved like an elephant but this elephant had done this dance before; by afternoon, the recording was flagged VOID BY COURT ORDER, a scar across a line in a system that mostly assumes everyone plays fair. The sign in my old yard came down. The proceeds—minus the earnest money deposited by the couple with the crib on backorder—froze in a way that would resolve like a snowpack in March: slowly, inevitably, with measurements and signatures.

Walsh drove me back to Delaware at dusk, the sky the color of a bruise you stop touching. He left me at the door with an extra key and the kind of glance you give someone you hope you won’t have to save from a fire twice.

Inside, I made noodles and stared at the laminate. The safe house was quiet except for the house sounds that never leave you alone—fridge motor, pipes, the wind forgetting the angles of this siding. I washed my bowl with the little green sponge and turned the TV on for five minutes, then off again. The TV was a mirror I couldn’t afford to stand in front of.

The door buzzer sounded once, the code that meant ours. Chin stepped in with a banker’s box and a face that said don’t worry before I asked.

“Mail forward,” he said, setting the box on the table. “And a delivery from Property Management.”

I opened the smaller envelope. Inside was a folder with a checklist that made my eyes water. Philadelphia Residence: Quarterly Maintenance Log. Gutter cleared. HVAC serviced. Roof inspected. Lawns mowed. Motion lights updated. Paid. Paid. Paid. In the upper right corner, a stamped note: Protected Asset Verified — Do Not Divert.

The larger envelope held photographs: my house in the same golden light Derek had sold it under, but honest. A rake leaned against the porch. The newel post had a nick from the box I’d scraped the day I moved in. The hydrangea I planted had gone wild in the silence, a blue so loud it made me laugh.

I didn’t cry. My tears had an accountant. They disbursed on schedule.

I was on the third photo when my safe phone buzzed with a text from an unknown number that was very known. We need to talk, it read. —Amanda.

I texted Walsh three words: She has number.

He called, not texting back where my thumbs could get cute. “Do not respond,” he said. “Block. We’ll rotate.”

“I thought her superpower was Instagram,” I said. “How did she get this?”

“She’s married to your brother,” Walsh said. “He knows your old back-channels. We’ll close that gap.”

I blocked the number. Five minutes later, a notification from a news site: EXCLUSIVE: Sister Presses Charges, “Cold” Witness Ruins Brother’s Life, Says Family. The photo was me leaving the courthouse a month ago, cropped so close you could see where my lipstick had dried wrong.

Underneath the headline, a quote from Dad: “We forgive her. We just don’t recognize her.”

I put the phone face down.

Chin knocked softly and stuck his head back in. “Exterior check,” he said. “Heard a drone on the block.”

We stood in the doorway, looking out at a street like any other—porch pumpkins, a kid’s bike leaned under a stair, a van that had been parked too long. Chin scanned the eaves and the sight lines, then nodded, satisfied. “Probably a neighbor’s kid,” he said. “Or a realtor who didn’t read the memo.”

When he left, I lay on the safe house couch and stared at the ceiling and counted to eight over and over until my breath obeyed. Somewhere in the world, my family was rewriting me into the villain that made their old stories work. Somewhere else, a couple stacked boxes in a storage unit and cursed my name because the universe had used my life to rehearse their disappointment.

In the morning, Walsh took me to the federal building with the rooms I call the rooms with no windows and the people I call the people with too many files. We prepped for the big trial—the reason my life had gone into a box in the first place. There were charts with account numbers that looked like poetry if you knew what references to line breaks meant. There were slides for a jury that would one day be twelve souls who could be any of the people in my family’s living room or none of them.

An analyst I’d worked with early on—Langley by way of Lehigh, sharp as a corner in the dark—stopped me in the hall. “You okay?” she asked.

“I keep being,” I said.

She snorted. “Good answer. There’s a place in my neighborhood that makes real bagels. If you stay alive for two more months, I’ll take you.”

“That’s the best incentive anyone’s offered,” I said.

Back in the room with the charts, the agent in charge—Farrell, the kind of man who polishes his shoes inside his head—handed me a folder with a cover page that looked like a book jacket. Recruitment — Federal Financial Crimes (Civilian and Special Agent Tracks).

I blinked. “Is this a pep talk?”

“It’s an opportunity,” Farrell said, not blinking. “You read a ledger like a poet reads grief. We can use that.”

“I have a job,” I reminded him. “I quit it to do this.”

“You had a job,” he corrected. “You can have a career.”

He set the folder down and turned a page for me. Salary band. Benefits. Loan forgiveness. Clearance. Training. It read like a thing I would’ve burned for at twenty-two. It still lit a match.

“Think on it,” he said. “Not because you owe us. Because you might owe yourself something that isn’t hiding.”

When Walsh drove me back to Delaware, I held the folder in my lap and didn’t open it. We didn’t speak until he put the SUV in park.

“You look like you’ve been offered a life and told you could keep the receipt if it doesn’t fit,” he said.

“I don’t know if I want to belong to another machine,” I said.

“You’d be surprised how many machines run better when the right person oils the right gear,” he said. “Sleep on it. Say no in the morning if you want. The offer will still be there.”

“Is that how you did it?” I asked.

He considered. “I said yes to the part where I got to make people less dead,” he said. “I say no to almost everything else.”

I nodded. In the safe house silence, the idea sat like a guest who might be welcome if they stayed polite.

The next afternoon, Koh called. “He wants to plead,” she said without greeting. “Three years, restitution, five supervised.”

“Will he apologize?” I asked before I could stop myself.

“To me?” Koh said. “He doesn’t owe me an apology.”

“To me,” I said.

“He’ll write you a letter,” Koh said. “His lawyer asked if you’d read it.”

“I’ll open it,” I said. Which is not the same thing.

“K,” she said, her hard edges softening for a blink. “You did the right thing.”

“Everyone keeps saying that,” I said.

“That’s because it’s true,” she said. “And because it doesn’t feel like it, and people who’ve swallowed that pill try to hand the next person water.”

That night, I made pasta again and watched the footage of a storm slowly walking up the coast as if the Atlantic had a grudge. I slept on the couch and dreamed of my house emptying and refilling like a tide. In the dream, the hydrangea took over the living room and politely asked if it could stay.

The letter arrived a week later, hand-delivered by a woman with a bar card and the patience of someone who takes calls from men who used to think they didn’t need her. I’m not here to argue, she said at the door. He asked me to give it to you.

I slid it into a drawer and made it wait with the bills.

The marshals rotated my phone again. The GoFundMe for Derek stalled at $6,300 with a hundred comments arguing theology and property law. Mom posted a photo of a sunset with her hand in the corner of the frame like she’d been trying to hold it and failed. Forgive. Forget. Family wins, she captioned it, then removed my last name from her bio the next day.

Koh’s office sent me the formal document that voided the sale, the court’s seal of a machine admitting it had worked as designed. ORDERED AND ADJUDGED: the deed recorded as Instrument No. [redacted] is void ab initio. The phrase sat in my mouth like a foreign candy. Void from the beginning. If only.

Two weeks later, in a room whose lights had no switch I could find, I rehearsed my testimony for the case that had swept all of us into a narrative where crimes were lines on slides and victims were numbers in bank accounts and I was a woman who had decided decimals matter.

When we broke, Walsh leaned in the door and tipped his head toward the hall. “Your brother pled,” he said.

“I know,” I said. “Koh told me.”

“He’ll be in federal by Christmas,” Walsh said. “You won’t have to see him at the courthouse again.”

“I haven’t seen him since the living room,” I said.

Walsh nodded. “Sometimes that’s where it ends,” he said. “Sometimes that’s where it should.”

I picked up my folder. The hydrangea picture was still tucked inside the maintenance report, a blue bruise on good paper. I slid it into the back pocket of my bag.

“Chain of custody,” Walsh said lightly, nodding to the folder.

“What?”

“Lawyer joke,” he said. “It’s what we call it when the right thing ends up in the right hands, every step of the way.”

“Oh,” I said. “That. Yes.”

Outside, the sky did that November thing where it thinks it’s six at two. The wind lifted a few leaves and set them down gently in a line against the curb, like it was making room.

I went back to the safe house and turned on the lamp the marshals had put in the corner, its light a small circle like a promise made by someone who hated breaking them. I opened the folder Farrell had given me and I didn’t say yes and I didn’t say no. I set it next to the hydrangea photo and the letter in the drawer and the maintenance report that had become scripture.

And then I slept, because tomorrow would be a day where a prosecutor would ask me to explain math to twelve strangers in a way that made it feel like a door and not a wall, and I am very good at doors.

Part 3

The letter sat in the drawer for a week like a ticking clock I refused to hear. I did everything except open it. I alphabetized the spices in a kitchen I didn’t own. I learned the safe house thermostat’s quirks. I read the hydrangea maintenance note as if it might reveal a code. When I finally slid the envelope out and flattened its edges on the table, I wore latex gloves—half as a joke, half as a boundary.

Sarah, it began in Derek’s neat block print, the handwriting of a boy who turned in quizzes early because he liked the feeling of being done.

I don’t expect you to read this. I don’t expect you to answer. I’m sorry.

He said the things a man says when the system has shown him the shape of his choices. He admitted what he’d never admit in a room with witnesses: that he’d convinced himself I didn’t deserve what I built, that he’d wanted to win a race no one else was running, that jealousy plus opportunity equals crime if you drop the right variables.

I told myself I was keeping the family afloat, he wrote. But the truth is uglier: I wanted to prove I was the responsible one by stealing your proof.

There were no excuses—only confession, which is not the same as restitution. He ended with a sentence that landed and made a small crater in me: I hope you have a good life. You’ve earned it.

I folded the letter, slid it back into the drawer with the hydrangea photo and the recruitment folder, and went for a walk at 6 a.m. in a neighborhood where no one knew I existed. Dawn made the vinyl siding look like stone. Somewhere, a paper landed on a porch with a forgiving thump. I let the air do what it does best—remind me I am not only the sum of the rooms I’ve sat in.

When I returned, Chin was at the table with a laptop the color of serious. He angled the screen toward me. “You’re trending,” he said, not triumphantly.

A headline: “THE HOUSE THAT VANISHED: Expectant Couple’s Dream Home Voided by ‘Cold’ Witness Program.” Beneath it, a photo of the buyers—Jessa and Mateo—standing outside my porch with arms crossed and that particular expression people wear when the universe owes them something and forgot.

“We did everything right,” Jessa told the camera, mascara uncried, voice pitched to the key of reasonable outrage. “We saved. We hired a reputable agent. Now we’re stuck paying for a storage unit and we’re six weeks from our due date.”

The piece wasn’t cruel. It was worse—competent. It framed the story as system versus citizen, a tug-of-war between faceless policy and adorable nursery wallpaper. It didn’t name me, not directly, but the phrase protected witness was sticky enough to pick up dust.

“They’re not wrong to be mad,” I said.

“They’re wrong about who to be mad at,” Chin said. “But people don’t care about the direction of their anger, only its heat.”

Walsh arrived thirty minutes later with two coffees and a look that meant the thing he was about to say would be obvious and unpleasant. “You don’t contact them,” he said, setting a cup in front of me. “You don’t write a nice note. You don’t send a gift card to Babies R Us.”

“It’s BuyBuy Baby now,” I said, because pedantry is a refuge.

“It’s Chapter 11 now,” he said, because reality is not sentimental. “Point stands.”

“I won’t,” I said. “I know the difference between empathy and interference.”

He tapped his temple in a gesture that was both praise and please. “We’re going to control what we can. Koh’s drafted a statement that looks like a brick wall. Title is issuing refunds today. The buyers will be made whole before dinner.”

“What about the agent?” I asked.

“Being made acquainted with the words ‘due diligence,’” Walsh said dryly. “And with the registry they didn’t check.”

He slid a second folder toward me. TRIAL PREP — WEEK 1. Tabs in a courtroom rainbow. A witness list with my name in bold where the judge’s clerk would see it and make a small note with a number two pencil.

“Opening statements Monday,” he said. “You’re on Day Three. We’ll go through your direct again this afternoon.”

“I know it,” I said.

“You know it,” he agreed. “But the jury doesn’t yet, and they can’t read your mind.”

“My mind is very legible,” I said. “It’s my life that keeps getting redacted.”

He didn’t disagree.

The big case woke the courthouse up like a fire alarm. Reporters and sketch artists formed a polite wolf pack outside Security. The defendants arrived in dark suits with expressions taught by experience: don’t look at the camera, don’t look toward the seal, don’t look like a villain. The lead defendant—Roth—wore a navy suit that cost five good decisions and a tie in a color rich men use when they want to look like they’ve been wronged.

Koh stood in front of twelve strangers and taught a graduate seminar in story. “Ladies and gentlemen,” she began, not smiling, not scowling, just level. “This is a case about arithmetic and arrogance.”

She walked them through the skeleton: cash-intensive businesses, skimming, structuring, deposit patterns at 4:58 p.m. because crooks are superstitious about the quarter hour. She introduced me with a slide that read S. MITCHELL — Senior Accountant and the bland headshot from a time when my bangs were a decision I should apologize for.

“Ms. Mitchell noticed something boring,” Koh said. “Fractions that didn’t land where math says they should. She asked the right questions. The answers led here.”

The defense tried on three masks in its opening: this was a witch hunt; this was normal business; this was a misunderstanding. Their PowerPoint used serif fonts as if that proved innocence. One of the lawyers—a man whose hair had been engineered to withstand a hurricane—said “coincidence” so many times it lost its corners.

Day One was bank records. Day Two was an IRS agent with the kind of dry delivery that secretly makes juries lean forward. Boring is credibility when money is on trial. Day Three was me.

I took the stand in a black suit I’d bought at an outlet with federal per diem. I placed my right hand on a Bible that had been touched by more strangers than a subway pole. I said the words. Walsh watched from the second row, chin tilted, arrest warrant tucked invisible in his pocket because that is who he is everywhere.

Koh took me through the foundation like she was setting a table. My education. My job. The day I saw the decimals behave like liars.

“What did you do?” she asked.

“I reported it,” I said.

“Why?”

“Because numbers tell the truth if you let them. And because when they don’t, something dangerous is happening.”

“Did you benefit financially from reporting it?” she asked, because she knew defense would ask if she didn’t.

“No,” I said. “It ruined my life,” I didn’t add, because jurors prefer facts to blood.

We put the charts on the screen, and I walked them through a slide I had built in a previous life: Pattern X: 29 consecutive deposits under $10,000—avoidance behavior consistent with structuring. I saw Juror 6 nod, a teacher by the clothes, a knuckle-tapper by habit. I saw Juror 9 frown, an accountant maybe, or a man whose father had worked in a bank and taught him that money is timid unless someone tells it what to do.

The defense cross was polite weapons. “You’re not a law enforcement agent, are you?” a lawyer asked, faux-kind. “You’re not trained to investigate crime. You’re just… an accountant.”

“Just,” I repeated, smiling without showing teeth. “Yes. I follow rules. That’s what accountants do. We know where numbers belong. When they show up where they shouldn’t, we ask why.”

He tried to get me to admit to ambition, as if telling the truth for a living were a career plan. He suggested I’d sought attention. He suggested I had a vendetta against rich men. He suggested I couldn’t be trusted because my own family—he stopped when Koh stood, objecting so fast she didn’t rise from her knees. The judge sustained. The jury got a free lesson in boundaries.

We recessed for lunch. In the hallway, a blogger with a microphone that had a foam cube asked me, “Do you feel bad for the couple who lost the house?” Walsh stepped between us before I could respond. “No comment,” he said, but the cameras captured my face anyway, which betrayed the treachery of being a person who does, in fact, feel bad about a lot of things she did not cause.

Back on the stand, we finished the tour of deposit slips and ghost invoices. Koh sat, satisfied. The judge thanked me like I’d handed him a stapler. I stepped down. On the way back to the bench where witnesses sit and memorize carpet fibers, my phone buzzed in my pocket with the distinct rhythm of Walsh’s code: Do not look. Walk.

When the afternoon session ended, Walsh led me down a hall that smelled like printer ink and metal, the back way out. He didn’t speak until the door shut behind us.

“We’ve got a leak,” he said.

I stopped. “From where?”

He didn’t answer the question I asked. “A post went up during your testimony,” he said. “A photo from three weeks ago. You—at a coffee shop near the Delaware safe house.”

My throat tightened. “Who posted it?”

He held out his phone. A screenshot: @CityWatchDude — “Spotted: Protected witness (!!!) hanging out at Java Harbor in Claymont. Marshals parked outside. Whole thing is theater. #waste #DeepState.” Six thousand likes. Two thousand retweets. Three dozen replies with the kind of profile pictures that make you move your wallet to the other pocket.

“It’s a zoom from across the street,” Walsh said. “Grainy, but it’s you. Timestamp checks out.”

“I didn’t see a camera,” I said.

“You weren’t supposed to,” he said. “We think someone in the coffee shop recognized you from TV and sold the tip with a phone photo. The account belongs to a hyperlocal ‘accountability’ guy with a Patreon and bad judgment.”

“Is my location blown?” I asked.

“We’re moving you,” he said. “Tonight.”

He texted Chin. Bag. Car. Burn phones. Then he dialed Koh. “We’ve got a splash,” he said. “Not enough for the defense to use in court, but enough for some idiot to park outside and get cute.”

Koh swore in a way that sounded like a closing argument. “I’ll file a protective note,” she said. “But get her out. The last thing I need is a YouTube vigilante sticking a camera in her mailbox.”

“Already on it,” Walsh said. He ended the call and looked at me. “You okay?”

“I’m tired of being brave,” I said.

“Then be stubborn,” he said. “It requires less adrenaline.”

We rode to the safe house in silence, lights off, taking a route that felt like a maze a rat would give up on. Chin had already packed—two bags, a folder, three phones, the maintenance photo, the letter left in the drawer where it belonged. He’d wiped the counters, because he is the sort of man who leaves a place cleaner than he found it, even when no one will invoice him for that service.

“This way,” he said, and guided us out the back through a fence that opened where a fence should not.

“Where to?” I asked.

“Somewhere less predictable,” Walsh said.

We drove to a hotel off I-95 that catered to sales reps and people who lose their keys. It had a lobby plant that didn’t know it was plastic. Walsh booked us under names that were plausible without being memorable. We used the service elevator. Chin made three trips with nothing in his hands, so the second-floor camera would record the wrong number of comings and goings.

In the room, Walsh set the deadbolt and the chain, then pulled a roller shade that blacked the world out like a single gesture could fix everything. He locked eyes with me.

“I need to ask you a question you won’t want to answer,” he said.

“Ask it,” I said.

“Did you tell anyone—anyone—about the coffee shop? A friend? A neighbor? Family. Even in a way you thought was harmless.”

“No,” I said, then paused. “I… posted a photo to a private cloud album three weeks ago—hydrangeas in front of the shop. I sent it to myself because I liked the way the blue looked next to the brick. That’s it.”

“From your marshal phone or your civilian?” he asked.

“Civilian,” I said.

He blew out a breath through his nose. “Clouds leak,” he said. “Even the good ones. Even when you’re careful.”

“I know,” I said, because I do this for a living—just with money, not pixels.

“We’ll rotate everything again,” he said. “Numbers. Patterns. Routines.”

I nodded. “I can be replaced,” I said, and meant it the practical way, not the emotional way.

“No,” Walsh said, and there was a softness he usually keeps in the glove compartment. “You can be moved. You can’t be replaced.”

We settled into the choreography of temporary: toothbrush in a baggie, shoes lined up by the door, chair in front of the window because people are stories and stories prefer cover. The TV showed me my own face again, pixelated, paused, the voiceover telling America what I cared about and what I didn’t like it knew. I switched it off.

At 2 a.m., my phone buzzed—a code we hadn’t used before. Walsh was already standing, hand up for quiet, ear bent toward the door.

“Fire alarm,” Chin said, crackling through the radio. “Two floors down. Could be nothing. Could be someone pulling it to see who runs.”

We didn’t move. The hotel’s alarm was a shriek designed by an engineer who hates sleep. Red lights pulsed in the hall like the building was breathing wrong.

“Stay,” Walsh said, and slipped out with his badge in his palm and his other hand in a posture that meant we weren’t going to pretend.

He returned three minutes later smelling like dust. “Kid with a vape,” he said. “Security is on it. No eyes in the lot.”

The alarm cut out. Silence poured back in like water. I exhaled a breath I didn’t know I’d been hoarding.

“You’ll testify again tomorrow,” Walsh said. “Then we’ll move you again. Less coffee shops. More room service.”

“I hate room service,” I said.

“Everyone does,” he said. “That’s why it works.”

I didn’t sleep. At 5 a.m., I made hotel coffee with the machine that tastes like it was designed during a war. At 7 a.m., we were back at the courthouse, entering through a door that smelled like institutional soap. I took my seat in the witness chair that had become furniture my body knew.

Defense tried a new angle: suggest I wanted fame. “You’ve been in the news a lot,” the hurricane-hair lawyer said. “You seem to be comfortable with attention.”

“I seem to be alive,” I said. “If attention is a by-product of telling the truth, I’ll accept the side effect.”

He opened his mouth to get clever, then closed it. Koh stood. “Redirect?” she asked. The judge nodded. She approached with a half-smile reserved for witnesses who do not need rescuing but deserve reinforcement.

“Ms. Mitchell,” she said, “why are you here?”

“Because math matters,” I said. “Because people with money count on other people not counting.”

Koh turned to the jury. “No further questions.”

At recess, Walsh handed me a printed email. From Title: Funds returned to buyers; escrow closed; all parties notified. There was a small red stamp in the corner only a bureaucrat could love: RESOLVED.

“They’re whole,” Walsh said.

“Except for the story,” I said.

“Stories scar,” he said. “But they heal.”

Back at the hotel, a box waited at the front desk with no return address and handwriting that leaned too hard on the downstrokes. The clerk glanced at me like he knew he should not hand this to a person like me, then did anyway because the tag matched the name on the reservation. Walsh took it with two fingers, as if it might bite.

Upstairs, he opened it with a pen, blade out. Inside: a baby blanket, pale yellow, hand-knit, and a card: For the couple you hurt. If you had a heart, you’d pass this on. No signature. No return.

I laughed, because sometimes the only option is absurdity. “I can’t even knit,” I said.

“It’s bait,” Walsh said, bagging it. “And it’ll go into evidence with the other bait. People who think they’re making points are mostly leaving fingerprints.”

He slid the evidence bag into his case and moved on like a man used to disposing of other people’s theater. He sat, rubbed his eyebrows, and looked up at me.

“You’re doing well,” he said, and because he rarely says that, I felt it land.

“Define ‘well,’” I said.

“You’re still telling the truth,” he said. “And you still know what’s yours to carry.”

I nodded. The recruitment folder pressed light against my shoulder from inside my bag, weightless and heavy in the way decisions are. I hadn’t said yes. I hadn’t said no. I was in the middle of a sentence, and the punctuation hadn’t revealed itself yet.

Before dawn the next day, Chin knocked with a new plan. “We’re moving again,” he said. “The leak account posted a photo of a parking lot that looks a lot like ours.”

“Does it look like every parking lot in America?” I asked.

“It doesn’t matter,” Walsh said. “Paranoia is a tool too.”

We packed. We drove. We reached a place I won’t describe except to say the walls were older and the curtains heavier and the carpet had a pattern designed to hide sins. I set the hydrangea photo on the nightstand and the letter under it, like a paperweight for memory.

My phone buzzed—an alert from a news site I’d forgotten to mute. DEFENSE LEAKS “ANON SOURCE” CLAIM: WITNESS ENJOYING “FREE VACATION” ON TAXPAYER DIME. The photo: a blurry frame of me in the courthouse hallway, eyes down, mouth a line.

I closed the alert and lifted my eyes. Walsh was already watching me. “Remember what I said about convincing?” he asked.

“I remember,” I said. “I’m not in the business of changing minds that don’t want to be changed.”

“Good,” he said. “Because tomorrow is closing arguments. And then you get to go home.”

“To where?” I asked, and the question hung there like a choice.

He didn’t answer. He didn’t need to. Home was a noun I would need to build into a verb again.

That night, I slept for three unbroken hours. In the dream, I put a SOLD banner across a photograph of my own fear. It looked better than I expected.

In the morning, the judge reminded the jury that arguments are not evidence and evidence isn’t optional. Koh stood and drew a clean line from decimal to handcuff. The defense assembled a collage out of maybe and perhaps and surely. The judge sent the jury out with a stack of instructions that read like a map drawn by a lawyer who hates art.

We waited. We counted the seconds by the vending machine’s hum. Walsh bought a bag of pretzels, then didn’t eat them. Koh practiced not pacing. I memorized the stain on the carpet that looked like an island off a coast I couldn’t afford.

At 3:17 p.m., a buzzer announced that twelve people had finished a story. We filed back in. The clerk read the sheet with the voice of a person who knows their words will live in someone else’s memory for decades.

Guilty. Guilty. Guilty. Each one a small stone dropped in a still pond.

Roth’s jaw clenched. His lawyer put a hand on his elbow. Koh didn’t smile; her shoulders simply lowered half an inch, like someone had finally taken a box from her arms.

Outside, the sidewalk filled with microphones like flowers. “No comment,” Walsh said for me, for Koh, for the world. We slid into the SUV, shut the doors on noise, and breathed.

“You did it,” Walsh said.

“We did it,” I said. “With decimals.”

He grinned, walking back an inch of his reserve. “You want to open your recruitment folder now or after pizza?” he asked.

“After,” I said. “Because I’m about to do something radical.”

“What’s that?”

“Eat until I can’t hear my own thoughts,” I said.

He laughed, a brief clean sound I wish I’d saved for later.

The pizza arrived in a box that said Family Size in letters that didn’t know what that meant. We ate in silence. When we were done, I put the hydrangea photo on the bed and the folder next to it and the letter beneath. I looked from one to the other and thought, chain of custody—what belongs where, at each step, to keep the story intact.

My phone lit up with a new number—unknown, likely a reporter. I didn’t touch it. It buzzed again. And then again, with a code I did recognize, one that hit like cold water.

Walsh’s face had already changed shape. He held up his phone. “We’ve got a problem,” he said.

The problem was a screenshot: a post from a private Facebook group that wasn’t private enough. Aunt Diane had uploaded a photo from Mom’s birthday, and in the background, reflected in the mirror above the mantle, was me… and a marshal’s badge clipped to Walsh’s belt, the edge of the seal visible, the date stamp on the photo clear.

“Pray for our family,” the caption read. “We are under attack, but we stand together.” The comments were a bonfire.

Chin swore under his breath. “That’s enough data points for anyone who wants to play detective,” he said.

Walsh’s eyes were already calculating routes. “We’re not sleeping here,” he said. “Pack now.”

I grabbed the photo, the folder, the letter. I put them in the bag with the practiced speed of a person who has learned to travel with her life in her hands.

“Where?” I asked, shouldering what mattered.

Walsh opened the door to the hall. “Somewhere their stories can’t find you,” he said.

We moved.

Part 4

The recruitment folder thumped against my hip as we sprint-walked down the hotel corridor that smelled like overboiled coffee and carpet cleaner. Walsh led, one hand at his belt, the other at the keycard, shoulders squared to turn his body into the door ram he’s had to be on too many Wednesdays. Chin took rear guard, eyes in the back of his head the way only men who’ve been ambushed learn.

“Stairs,” Walsh said, not quite a whisper. The elevator dinged and sighed open for a stranger who didn’t know he’d just missed becoming a footnote. We took the concrete stairwell two flights down, then out through a service hallway lined with ice machines that hummed like mosquitoes.

The back lot was a lesson in silhouettes—dumpsters, a chain-link fence, a light that flickered in a Morse code for not today. Walsh’s SUV sat with its nose pointed toward the exit, the way the manual says, the way habit becomes doctrine. He popped the hatch; Chin slid our bags in and closed it with a patience that belied urgency.

“Where?” I asked, breath steady from the adrenaline drip that had replaced caffeine in my life.

Walsh didn’t answer until we were on the interstate, orange sodium lights bending across the windshield like lines on a chart. “A place with fewer windows,” he said.

“Prison?” I said.

He cracked half a grin. “Better snacks.”

We drove in silence long enough for the playlist of my thoughts to get to Track 3: What does Aunt Diane think she’s doing? followed by What if the wrong person can triangulate those pictures? followed by Why did I let hope have a key to my ribs and call it family? The recruitment folder stared at me from the floorboard like a pamphlet handed out by a kindly cult.

“Talk to me like I’m a juror,” I said, finally. “What exactly is the risk from that post?”

Chin answered, tone clipped but not unkind. “People crowdsource harm. A reflection in a mirror gives you height of a badge relative to a mantle. Combine with a real estate listing photo and you get room layout. Timestamp plus daylight equals time of day. Metadata on the upload—if they didn’t strip it—gives you device model. Combine with Mom’s location tag habits, and you narrow the radius.”

“Plus,” Walsh added, “some folks just want to be near where the story is. They drive by. They lurk. They film. Ninety-nine percent are harmless. It only takes one percent and three bad minutes to change a life.”

“What happens to the post?” I asked. “Can Koh get it taken down?”

“She’ll try,” Walsh said. “Platforms like to pretend they don’t work weekends. By Monday, it’ll be screenshotted to death.”

I rubbed my eyes. “I keep wanting to write a statement to the internet like I’m applying for mercy.”

“Don’t,” Walsh said. “The internet is not a court and it’s never merciful.”

We left the interstate somewhere I couldn’t triangulate without a map, turned down a road lined with warehouses whose names were proper nouns in faded paint—SEAFORD, KELLER, CUMMINS—then into a gate that opened because the camera recognized Walsh’s license plate. The building beyond looked like any other—brick, cinderblock, too many vents. Inside, the air was recycled at a higher standard than the rest of the world. The corridor had no windows, which means the corridor had no lies.

“Welcome to a facility that does not exist,” Chin said dryly. “Or at least not on Google.”

They put me in a room that was half office, half monk’s cell: a cot, a desk bolted to the floor, a chair with the exact amount of lumbar support required by regulation and not an ounce more. Walsh keyed a code into a wall panel and the hum of the HVAC shifted an imperceptible degree.

“Layered security,” he said. “Anyone who opens the outer door without the right key trips a noise you’ll feel in your teeth.”

“You’ve thought of everything,” I said.

“No,” he said. “We’ve thought of the things we’ve already survived.”

He handed me a government hoodie in a shade of gray that exists nowhere in nature. “Put this on if you need to move between rooms. Cameras don’t love patterns.”

“I’m very pattern-forward,” I said, tugging it over the T-shirt I’d been wearing since arguments began.

“Thought so,” he said, checking the peephole like it might have spontaneously invented a new problem.

We debriefed the threat, the route, the next twelve hours, the next twelve days. He didn’t ask me about the recruitment folder; I didn’t tell him it had started to feel heavier than its paper weight. When he left, he paused with a hand on the knob.

“Try to sleep,” he said.

“You always say that like it’s a suggestion you know I’ll ignore,” I said.

“I always say that because one day you won’t,” he said, and closed the door with the softness of a man who’s learned to make entrances and exits sound unimportant.

The facility had time where the world had noise. I woke after three hours, surprised. I showered in water that hit the exact temperature an engineer who reads specs would pick. I made coffee in a machine that believed taste was a rumor. Chin knocked twice, the code for friendly, and slid in with a tray: oatmeal, eggs, an orange that might have dreamed of being sweet.

“We pushed Aunt Diane’s post through platform channels,” he said between eggs. “Koh got a preservation order so we can pull the metadata later. We’re filing a request to seal your mother’s birthday album. The defense won’t get to use it next week.”

“I don’t care about the defense,” I said. “I care about the man with time and a tank full of gas.”

“We’ve spread a decoy scent,” he said. “Social chatter already thinks you’re in three different states. It’s amazing how little truth can do when rumor’s working overtime.”

He set a printed sheet on the desk. US v. Roth — Jury Verdict Filed. I ran a finger over the stamped words like they were braille I could learn to see. GUILTY looks like any other word if you don’t know what it cost.

“You did good work,” Chin said. His compliments are as rare as Walsh’s and twice as carefully wrapped.

“I told the truth about math,” I said. “Koh made it sound like a story.”

“Stories save lives,” he said, surprising me—and maybe himself.

He left with the tray. I sat and opened the recruitment folder because reality had narrowed my choices into a shape I recognized from spreadsheets: two columns, plus/minus.

Pros: Put the skills that wrecked my old life to use in a way that builds a new one. Salary that says we mean it. Benefits that say we know you’ve seen things. A team that has my back by doctrine, not nostalgia. A badge that opens doors and closes mouths.

Cons: The machine. The loss of anonymity that pretends to be safety. The understanding that every victory makes someone swear you’re part of the problem. The knowledge that family will use my choice as proof in a case they tried years ago: Sarah vs. Us.

I closed the folder and stared at the wall, which stared back without malice. Walsh’s face appeared in the little square of safety glass.

“Visitor,” he said. “Authorized.”

“I didn’t put anyone on the list,” I said, panic and curiosity shaking hands.

“Defense counsel,” he said. “Your brother’s attorney. She’s got something you’ll want to hear. Koh cleared a monitored conversation if you’ll have it.”

“Monitored,” I repeated.

“You’ll be on camera,” he said. “I’ll be on the other side of the glass. She brings in a pen that clicks wrong, we confiscate it.”

“Fine,” I said, the word catching in my throat like lint. “Five minutes.”

He nodded and disappeared. A minute later, the door opened, and Jennifer Walsh—no relation to my Walsh—walked in, suit rumpled at the cuffs, hair pulled back in a way that said courtrooms, not salons.

“Ms. Mitchell,” she said, a small nod. “Thank you.”

“You’ve met my marshal,” I said. “He comes with the room.”

“He’s very attached,” she said, and the corner of my mouth acknowledged the joke.

She set a manila envelope on the table. “Your brother asked me to deliver this in person,” she said. “Not a letter this time. Something you might need to see.”

I didn’t reach for it. “I’m not in the market for apologies as currency.”

“It’s not an apology,” she said. “It’s a statement—a sworn one. He filed it this morning in the civil proceeding the buyers’ agent is trying to start to rescue their commission.”

My eyebrows went up before I could stop them. “He’s… telling the truth?”

She nodded. “On the record. He admits to forging your signature. He admits to fabricating the notary seal. He admits to knowing he lacked authority. And he writes, and I quote: I saw value and I wanted it more than I wanted to be a decent brother.” She slid the envelope closer. “I’ve been practicing twenty years. I don’t see that sentence often.”

I took it, my fingers steady. “Why tell me?”

“Because you’re a witness and a sister,” she said. “You’re allowed to be both. And because a judge asked me to convey a note as well—informal, off the record. It reads: Ms. Mitchell may rest easier knowing the record will not be bent around her by the lazy lies of others.”

Something behind my eyes went tight and then let go. I blinked once. Twice. “Thank you,” I said.

Jennifer glanced at the glass, knowing, I suspect, that men with badges were watching my face for its weather. “One more message,” she added, voice lower. “From Derek. He said: Tell her I know what ‘consequences’ means now. Tell her she didn’t do this to me. I did this to me.”

The sentence landed like a small bird you weren’t expecting to catch. “He’ll serve three?” I asked. “With good time?”

“Likely,” she said. “Then five supervised. Then the long part.”

“The long part?” I asked.

“Becoming the man he thinks he is,” she said, and stood. “Good luck, Ms. Mitchell. For what it’s worth, I’d hire you to audit my books.”

“Don’t say that too loud near the AUSA,” I said. “She’s already recruiting.”

“I hope she succeeds,” Jennifer said, and left with a nod to the glass.

Walsh slipped in a minute later and didn’t ask the question on his face. He looked at the envelope in my hands and pointed to the corner of the room where a scanner sat like an afterthought.

“I’ll copy and file,” he said. “If you want.”

“I want,” I said. “Make a copy for Koh. One for Title, if they need it. One for… me.”

He scanned. The machine hummed like relief. He handed the original back. It felt less like exoneration and more like the world finally agreeing to write down the thing I’d known.

“Next,” he said, businesslike again because that’s how we keep from drowning. “We need to talk about your house.”

“My house?” The word still felt like a taste I wasn’t sure I remembered properly.

“Property Management wants to schedule a walkthrough,” he said. “Standard post-incident. They’ll swap the locks—again. Inspect the alarm—again. Stage it—again. Then you have choices.”

“Sell or stay,” I said, opening the envelope and sliding the statement behind Derek’s letter like a parenthesis.

“Or rent,” he said. “Or keep as a base while you decide where your life lives now.”

“Where does my life live now?” I said to no one.

He didn’t answer. He’d already done me the courtesy of not pretending to be a philosopher.

“Also,” he added, almost as an afterthought, “the buyers sent a note through Title. They asked that a message be passed on to you—We’re sorry we said your name out loud. We were angry at the wrong people. They included a photo of their baby, due any minute, wrapped in a blanket that looks… hand-knit.”

I barked a laugh—sudden, involuntary, the kind that says we are absurd animals, all of us. “Did you tell them I don’t know how to knit?” I asked.

“I told them we appreciate the sentiment,” he said.

We ate lunch in a cafeteria that had been designed by someone who thought beige was a personality trait. My phone vibrated once with Koh’s name.

You were superb, she texted. Verdict makes case law; the leak won’t touch it. Also: I heard about the recruitment folder. I don’t poach. I just… approve.

I typed Thinking. She responded with Good. The people who think before they join are the only ones I want on my side.

That night, I lay on the cot and stared at the ceiling that never goes dark because the fluorescent world doesn’t sleep, it idles. The recruitment folder sat open on the chair. The hydrangea photo lay on top of it, blue against navy cardstock, like the sky had left a Post-it.

The choice wasn’t as much about the job as it was about grammar. Am I going to keep being past tense—what happened to me—or am I going to write in present—what I do? I hadn’t known until then how much I wanted verbs that belonged to me.

In the morning, I told Walsh before coffee. “Yes,” I said, finding the punctuation as I said it. “I’ll take the offer.”

He didn’t smile big—he rarely does. But the approval in his nod felt like heat on a cold hand. “You’ll be good at it,” he said. “You already are, you just don’t have the badge.”

“And the bureaucracy?” I asked, already self-mocking, already defensive of a life I hadn’t started.

“You survived worse,” he said. “Also we have decent jackets.”

We drove to a federal building in a city I won’t name and went up in an elevator that required a card and a code and the willingness to pretend you don’t feel your pulse in your ears. Farrell met us in a conference room with a view of a parking lot designed by a committee.

“You sure?” he asked without ceremony.

“Yes,” I said.

He slid a stack of forms across the table—background questionnaire, SF-86, the kind of interrogatory that requires you to remember a roommate’s middle name from a decade ago and whether you ever traveled to a country whose letter begins with Q. “This is the part where we pretend paperwork is personality,” he said. “After this, we train you to do what you’ve already done in a hundred rooms.”

“What about the trial?” I asked. “I’m still a witness for sentencing.”

“You’ll still be a witness,” he said. “We just may start paying you to write your reports with our fonts.”

I filled in boxes. I listed every address I’d lived at, leaving out the ones the government had created for me because the government already knew the government’s lies. I put down references who had seen me tell the truth and not apologize for it. I wrote ACCOUNTANT in the space for primary skill and added NARRATIVE in the margins because numbers are useless unless you know how to make them sing.

When we were done, Walsh walked me back to the car. The air had that late-fall snap that makes you think of school supplies and second chances.

“When do I get a jacket?” I asked, half-teasing, half-earnest.

“When you survive quant, shoot, law, ethics, and the part where we teach you not to trust anyone,” he said. “So never, but also sooner than you think.”

He dropped me back at the facility that doesn’t exist on maps, and we did the thing we always do: pretended that everything is normal long enough to make it through the hour.

Two days later, Property Management walked my house like surgeons—quiet, efficient, compassionate because it’s their job to be. They left a binder on the kitchen island: REENTRY CHECKLIST in bold on the cover. Inside: lock changes documented, alarm sensors tested, motion cameras calibrated, mail hold lifted. A yellow sticky on the last page: Welcome back when ready. —PM Team with a tiny doodle of a house that made me laugh harder than it deserved.

I flew in the back of a plane that didn’t take passengers, landed at an airport that takes freight, got into a sedan that takes orders. Walsh drove. He pulled onto my block the way you pull off a bandage—decisively.

Philadelphia looked like it always has when it’s trying to impress no one: brick too stubborn to quit, trees with leaves making a mess of themselves, a neighbor’s chair to save a parking spot, the economy of territoriality.

Walsh parked. I stood on the sidewalk a foot from my porch and let my eyes remember before my feet. The hydrangea had been trimmed, disciplined into a shape that would bloom again when it was ready. The porch light was off. The key in my hand was new, but the weight was familiar.

“You want me to go in first?” Walsh asked.

“Yes,” I said. “And no.”

He gave me the look he saves for moments when the right answer is the one your body knows. “No,” he said. “You go first.”

I slid the key into the lock. It turned smooth because a man in a uniform I never met had made sure of it. The door opened. The air smelled like paint cured and wood behaved. My living room looked both exactly as I left it and like someone had gently convinced time to tidy up.

I stepped in. The floor didn’t creak where it used to; someone had fixed that while I was gone. I set my hand on the kitchen island, cool quartz, and thought of the first night I’d cooked in this house—pasta and a cheap wine and a playlist called I Did It.

Behind me, Walsh stood in the doorway and did his job: looked outward while someone else looked in.

“You’ll need cameras,” he said, practical already. “And a motion light that lies to raccoons. And a neighbor who thinks you’re boring.”

“I can do boring,” I said, and believed it like a prayer.

He left me there with a new code on the alarm and a schedule of check-ins that felt like care, not surveillance. Before he went, he said one more thing—soft, like a question he’d been carrying around without permission.

“You picked a job,” he said. “Pick a home too.”

“I just did,” I said.

He nodded once and was gone.

I sat on my floor with my back against the couch and opened Derek’s letter again, then the sworn statement, then the hydrangea photo that now looked less like a relic and more like a promise. I stacked them in a new order: Truth, Consequences, Bloom.

My phone buzzed—an email chime I hadn’t heard in this house in three years. It was from a name I almost didn’t recognize because it had existed only in memos and whispered rooms: the pediatrician-buyer, Jessa.

Subject: A note you don’t owe us a response to.

Body: We got our money back. We closed on a smaller place. The baby’s here—she’s loud and perfect. We are sorry we said your name on TV. We were angry and you looked like a target. We know better now. If you ever need a favor that a physics teacher and a pediatrician can offer, we owe you one we can actually repay. —J & M.

I smiled in a way that wasn’t for any camera. I hit Archive. Some debts don’t require ledgers.

At dusk, I stood on the porch and watched the block invent dinner. A kid pedaled past on a too-big bike. A woman in scrubs yawned her way into a door. My hydrangea glowed in the last light like it had never considered not blooming again.

My phone lit with a call from Mom. I didn’t answer, not out of spite but self-respect. The voicemail arrived thirty seconds later: crying, a plea, a version of history edited for television. I saved it to a folder labeled Do Not Replay and went inside.

On the kitchen table, the recruitment folder sat next to a sticky from Property Management and the keys that meant welcome. I wrote a word in black ink on the inside cover where only I would see it, the kind of word you pin to a bulletin board in your head.

Begin.

I turned off the porch light. My house didn’t need a beacon to know it was mine.