February 5, 1945

Old Bilibid Prison, Manila, Philippines

You’re standing inside the cracked stone walls of a prison the Spanish built and three empires have used. The mortar is older than your country’s income tax. The air smells of lime dust, disinfectant, sweat—and something almost forgotten.

Freedom.

Not the full kind yet. There’s still barbed wire on the walls, guards at the gate, and a war raging on the far side of the ruined city. But it’s close enough that you can taste it, sharp on the back of the tongue.

Outside, American tanks clatter past on shattered streets, engines backfiring, boys from Kansas and New York who’ve never heard of Bilibid pointing at the old walls as if they were a museum. Overhead, U.S. planes drone lazy circles through the hot blue sky. For three years, that sound meant bombs and diving death. Today, it means something else.

They’re ours.

Down the central corridor, someone shouts, a voice that doesn’t quite fit in this stone-and-iron place.

“Men, listen up! You can write a real letter home. No Japanese censor. No twenty-five-word limit. Say what you want. The Red Cross will get it through.”

The words hit the crowd of prisoners like electricity.

Men who survived the Death March, who’ve watched friends starve, who’ve held buddies while they coughed themselves to death with zero medicine, suddenly look like the boys they used to be. They shuffle forward, weak legs shaking, eyes bright. A weapon is coming down the corridor, but not one made of metal.

A clipboard. A Red Cross armband. A stack of thin, precious pages.

In the middle of the crowd stands a Navy chaplain with a face carved down to angles by beriberi and hunger. His uniform hangs off him like it belongs to a bigger man and hasn’t caught up to the change. His name is Lieutenant Earl Ray Brewster, Sacred Heart, Oklahoma by birth, Methodist by calling, and by now chaplain to ghosts.

He reaches for the paper with hands that tremble more from emotion than from weakness. For the first time since 1942, he lets himself picture it: Rosella sitting at the kitchen table, the kids leaning in, his words—his actual words—unrolling across the distance like a bridge.

“This is a great day,” he whispers, more to himself than anyone else, “when I can write as a free man.”

Around him, something shifts. In a place designed to strip men down to numbers and bones, that thin sheet of paper has turned the whole cell block into a ticket counter back to the world.

1. The Pastor Who Thought He Knew Hardship

Five years earlier, Earl Brewster thought he understood sacrifice.

He’d grown up under the wide Oklahoma sky, where the wind never stopped and the soil remembered the Dust Bowl. Sacred Heart wasn’t much more than a church, a few storefronts, and a handful of stubborn families who believed God would see them through bad seasons as surely as He had seen their grandparents through Indian Territory.

Earl had answered his first call to ministry in a wood-plank church with hymns sung off-key and an offering plate that never felt heavy. He’d married Rosella, a girl with laughing eyes and iron in her spine. They’d had children who sat on the front pew and whispered to each other during his sermons.

He knew hard times. The Depression had taught every man in Sacred Heart how to stretch a dollar until it squeaked.

In 1940, when the Navy Chaplain Corps put out the call, he saw the same words in every headline: Duty. Service. Sacrifice.

He thought he understood.

He pictured lonely sailors on long sea tours, boys who needed someone to write their mothers and tell them their sons were reading their Bibles, sailors facing storms and homesickness, not bullets and bayonets.

He did not picture barbed wire under a tropical sun.

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor while he was already in the Philippines, assigned to Navy units around Manila. In December 1941, he woke up to rumors that a harbor he’d never seen was burning and the world had tipped on its axis.

By May 1942, the American defense of the islands had collapsed. Men were surrendering on Bataan, signs of a broken army shuffling into captivity. Earl had stayed with them. A chaplain doesn’t get a special lifeboat when the ship goes down.

They stripped him of his insignia, but not his vocation.

You can change a man’s clothes. You can’t take the call out of his bones.

2. The Valley of the Shadow

They didn’t put chaplains in officer camps.

That was one of the first bitter jokes Earl learned.

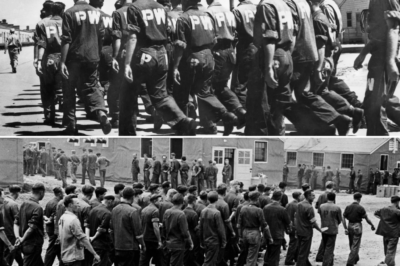

In the holding camps, in the dust and heat of the first months, Japanese guards lined prisoners up in ragged ranks like cattle at auction. Doctors, engineers, infantrymen, cooks. They sorted officers from enlisted. Anyone with medical training was huddled off into one group. Strong backs into another.

When they got to Earl, a Japanese NCO flicked a glance at his collar devices and made a face.

“Padre,” he said in broken English. “No gun, no sun. Work.”

So the man who’d enlisted to bring spiritual comfort to sailors found himself dragging logs alongside machinists, hauling rocks with farm boys, digging ditches with clerks.

He walked the same roads, wore the same lice in his clothes, watched the same men collapse.

The names blurred after a while—Cabanatuan, Davao Penal Colony—each one another section of the same hell. Stretches of bamboo barracks surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers, the air heavy with the smell of sweat and latrines and fear.

Davao nearly finished him.

By the time he arrived at the penal colony, malnutrition had chewed through him like termites. Beriberi swelled his legs and feet until standing felt like balancing on bruised melons. Protein-starved muscles melted away. His cheeks caved.

Navy records would later put it clinically: “So weakened by illness that he was not expected to live.”

The men around him believed it. They whispered to each other that the chaplain wasn’t long for this world. Plenty of strong men had gone under here. What chance did a small-town preacher have?

He heard the whispers.

He heard something else, too, in the quiet moments between work details—the insistent pull of a promise he’d made years earlier in a church with wooden floors.

Feed my sheep.

Davao had no pulpit. The guards didn’t care that he was clergy. They were equal-opportunity brutal.

By day, he hauled, dug, sweated without complaint. He knew he was no good to anyone dead. A man could not preach on an empty stomach, but he could pray while he dug.

By night, when most men crawled into their bamboo bunks, Earl started his second shift.

He walked through the barracks, checking on the worst cases—the men whose legs were too swollen to walk, whose eyesight had blurred to smears from vitamin deficiencies. He listened as they whispered fears they were too embarrassed to share with their buddies.

“I don’t even remember what my boy’s face looks like anymore, Chaplain,” a machinist from California would say, staring at nothing. “Just the picture on my bunk, and even that’s faded.”

“Write him,” Earl would say.

“With what?” the man would demand, bitter. “On what? And it won’t get through. The Nips won’t send it.”

“Maybe not,” Earl would reply. “But you’ll have said it. You’ll have gotten the words out. That matters.”

Sometimes he wrote the letters himself, pausing to ask how to spell a grandchild’s name, what street the house sat on, whether the dog still slept on the porch back home. He knew most of those scraps of paper would never see a mailbag.

But he also knew that a letter wasn’t always about reaching its destination.

Sometimes, a letter was about giving a man’s love somewhere to go.

Afterwards, when the barracks fell silent, he’d sit on an upturned crate under a dim lantern and open the tattered New Testament he’d managed to keep hidden through searches.

“‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death…’” he’d read, his voice hoarse from the day’s labor.

Sometimes they listened because they believed. Sometimes they listened because it was a sound that wasn’t orders barked in Japanese or a man screaming.

The stories were old, but the suffering was familiar.

You didn’t need to be religious to understand a God who had sweat blood and been nailed up by an occupying army.

On nights when he wasn’t reading from Scripture, he read whatever printed words he could get his hands on—pages from magazines that had somehow filtered in before the shutters came down, smuggled copies of Mark Twain or Jack London passed from hand to hand like contraband.

And letters.

On the rare, almost miraculous occasions when mail arrived, the barracks transformed.

3. Rumors and Real Letters

“Chaplain, they say mail’s coming.”

He’d heard that phrase so many times it barely registered anymore.

At Cabanatuan, at Davao, in every camp they moved them through, rumors sprouted like fungus after a rain.

“They say the war’ll be over by Christmas.”

“They say MacArthur’s on his way.”

“They say Red Cross parcels are in Manila.”

Most of the time, they say was a liar.

But every now and then, the miracle actually walked through the gate.

A Japanese officer, flanked by guards, carrying a small canvas bag. A list of names. A stack of thin envelopes.

Mail call in a Japanese POW camp wasn’t the cheery scene from the training films back home. There was no jovial sergeant tossing envelopes with a wisecrack for each. There were teeth clenched against hope and eyes fixed straight ahead, because to look eager was to tempt heartbreak.

Many men never heard their names called once in three years.

Some heard theirs exactly once.

The guards handed Brewster letters like they were performing a distasteful chore.

He turned the envelopes over in hands that shook.

The return addresses were strange and almost alien. Sacred Heart. Oklahoma City. A sister in Kansas. A twin brother whose name, Earl knew, would always be tied to his own.

The postmarks were old.

February 1942 on a letter he received in 1944. Postmen and censors and the chaos of war had carried them on a long, circuitous journey.

The censors had done their work. Whole lines blacked out. Phrases clipped. Any mention of German movements, of Japanese positions, of war news scrubbed clean.

The Japanese censors had done their own butchery. Letters back to families had to fit on tiny postcards, twenty-five words or fewer, in careful language.

“Conditions are good. We are comfortable.”

He’d been instructed to write those words even when his weight had dropped to the point he could count his ribs.

But right now, with an envelope in his hand that had actually crossed the ocean, those details didn’t matter.

He had a letter from home.

He was not a ghost.

In May 1944, more than two years into captivity, he hit what he would later call “a tiny miracle.” In a birthday letter to his twin brother—written on precious scraps, hidden until the censors would allow them—he described it as almost unbelievable.

“In the last two months,” he wrote, “I’ve received ten letters, including one from you, after hearing nothing for almost two and a half years. It was really something to get some mail after not hearing a word so long.”

Ten letters in eight weeks.

To a free man, it would have sounded like bad service.

To a POW used to hearing nothing, it was a flood. It was proof that in some little house in Oklahoma, Rosella still took out the good stationery on Sunday afternoons and addressed envelopes with his name. That his children still asked when Daddy would come home.

He didn’t keep them to himself.

In the barracks, a man with a letter was a man with a treasure. And treasure was for sharing.

He’d sit on his bunk while the others crowded close, holding his letter carefully so rough hands didn’t accidentally tear it.

“Chaplain,” a blind-sighted Marine would say from his corner, voice aching. “Can you…read yours out loud? Just so I can hear how the words sound.”

So he read.

“Dearest Earl,” he’d begin, clearing his throat.

He’d slow his cadence, savoring each word, not just for himself but for fifty men who closed their eyes and imagined a kitchen, a porch, the creak of a swing.

The letter spoke of ordinary things. Church suppers. A new dress Rosella’s sister had bought. The way the youngest had insisted that they keep setting an empty plate for Daddy at dinner.

No war news. No mention of rationing or casualty lists. The censors would’ve cut those anyway.

But between the lines, every man heard what they needed: I’m alive. You’re alive. I haven’t forgotten you. You still exist.

Sometimes a man with no letter at all would sit with his back against the wall and pretend.

For ten minutes, while Brewster read, he could imagine that the handwriting was his mother’s, his wife’s, his girl’s.

In that way, one family’s words became sustenance for dozens of strangers.

4. The Chaplain’s Job

The Navy had given Earl a rank. The Japanese had stripped him of the uniform.

But neither could change his job description.

Chaplain.

Not priest. Not preacher. Not morale officer.

Chaplain.

The man who showed up when the mail didn’t. When the Red Cross parcels didn’t. When a man’s faith had been kicked in the teeth once too often and he was ready to curse God and die.

He buried the dead.

He stood over shallow graves hacked into hard tropical soil, sweat running down his back, and said the same words over and over.

“At the resurrection on the last day, dear Lord…”

Sometimes he barely got through the first line before the air raid sirens howled and everyone dove for the nearest trench as American planes droned overhead. The guards screamed. Anti-aircraft guns thumped. Men flattened themselves on their bellies and covered their heads with their arms.

When the all-clear sounded, they climbed back out and picked up the burial where they’d left off.

“We didn’t mind the interruptions,” he would later write, dryly. “It meant liberation might be close.”

He held makeshift services where and when he could.

Sometimes in a bamboo frame chapel with a roof of palm leaves. Sometimes under open sky while Japanese guards stood near with rifles, curiosity and contempt mingled on their faces.

Some services were full. Men who hadn’t darkened a church door back home would sit quietly on logs, eyes following his hands.

Other services were small—a few gaunt figures on rough benches, their dog tags glinting.

He preached what he needed to hear himself.

That suffering didn’t prove the absence of God. That a man could be trapped in a cage and still, somehow, be free inside. That forgiveness wasn’t submission.

He did not preach easy answers or paint flimsy silver linings on the ugliness around them.

When a man cursed God for letting his buddy die of dysentery, Earl didn’t rebuke him.

“I think the Lord can take your anger,” he’d say simply. “He’s heard worse.”

Sometimes, the chaplain’s job was not to speak at all.

Sometimes, it was just to sit on the edge of a man’s bunk while he sobbed into a filthy blanket, and keep the silence from swallowing him.

And then at night, when he was so tired his own bones hurt, he’d pick up the New Testament again because half the barracks couldn’t read anymore.

“Chaplain?” someone would whisper. “You awake?”

“Unfortunately,” he’d answer.

“Read us something?”

And he would.

Not because it fixed hunger. Not because it cured disease.

Because it was the only way to remind them there was still such a thing as story and meaning and words you didn’t have to swallow.

5. Old Bilibid and the Sound of Planes

By late 1944, the tide had turned.

You didn’t need a radio to know it. You could see it in the guards’ eyes: fear where there’d used to be boredom. You could count it in the increasing frequency of air raids, in the distant thud of artillery, in the way prisoners felt a strange, disorienting emotion they’d almost forgotten.

Hope.

They moved Brewster again, this time to Old Bilibid Prison in Manila.

Bilibid was not a fresh camp built to hold POWs. It was old stone and iron, built by colonial hands long turned to dust. It had held criminals, rebels, inconvenient people through three flags. Now it held what the Japanese high command, in their blunt paperwork, called “cripples”—men too broken to be useful slave labor, too much trouble to move to other islands.

Official U.S. reports later described them more clinically as “seriously ill and wounded prisoners of war.”

One Navy history used a harsher term: “wrecks.”

He walked the cell blocks and saw what three years of captivity did to a body.

Men with one leg, hopping carefully between bunks. Men whose eyes were milky blanks, optic nerves eaten by deficiency diseases. Men whose stomachs stuck out against their spines in cruel parody of a beer belly while their arms looked like broom handles.

His job did not change.

He still buried the dead.

He still read at night.

He still listened when men whispered questions too shameful to say aloud under the Christ in the chapel.

“Chaplain…if I don’t make it, will you…tell my wife I thought of her at the end?”

“I’ll tell her,” he’d promise. He knew most of those wives would never find him, and he would never find them. But he made the promise anyway because it was the only thing he had to give.

He noticed the planes more here.

Over Bilibid, American bombers and fighters were no longer rumors. They were daily visitors, growling overhead on their way to crack open Manila piece by piece.

“We did not object to the planes,” he wrote later with wry candor. “It meant the day of our possible release was drawing nearer.”

The guards objected heavily. They shouted, ran, hid. They listened to the thunder in the distance like men who’d dug their own graves and were waiting for someone else to push them in.

On February 4, 1945, the thunder arrived at Bilibid’s gate.

American troops smashed into Manila that day, steel and fire meeting a cornered enemy.

For the prisoners, liberation did not look like raising a flag in a photograph.

It looked like confusion.

Orders in English instead of Japanese. Men in uniforms that felt familiar. Tanks in the streets.

It looked like guards who’d been gods for three years suddenly dropping their rifles and trying to melt into the shadows.

Some prisoners were too sick to stand. They lay in their bunks and listened to the battle sounds with eyes closed.

Others dragged themselves to the windows, skeletal fingers clutching at bars, desperate for a glimpse of a helmet with “U.S.” stenciled on it.

Earl walked among them, heart pounding in his wasted chest.

“Easy now,” he murmured. “Let the boys do their work.”

He didn’t feel much like shouting for joy.

He felt…dizzy.

Like someone who’s been underwater too long and surfaces too fast.

Freedom hurt the lungs.

6. The Great Day

A few days later, when the shooting had moved farther down the city and the lines were clearer, another kind of visitor came through Bilibid’s gates.

No rifle. No helmet.

A white armband with a red cross on it. A clipboard. A suitcase full of paper.

The man was young, American, his face carefully neutral—trying not to show too much of what he felt as he walked past rows of men whose uniforms hung off them like laundry.

He cleared his throat in the central corridor.

“Listen up, men,” he called, trying to sound brisk and businesslike. “Here’s how this is going to work. The Red Cross has arranged for each of you to write one letter home. Not a Japanese card. A real letter. No enemy censor. No twenty-five word limit. Say what you want, as long as it’s not military secrets. We’ll get it through.”

For a second, no one reacted.

Heiress of false hopes had made them cautious.

Then the words sank in.

Real letter.

No censor.

The sound that rose was not a cheer. Not quite. Their throats weren’t ready for cheering.

It was more like a collective, ragged exhale.

Earl felt his knees weaken.

Later, in a training pamphlet printed for Navy chaplains, he would describe it in the understated language that military writers favor:

“A few days after our liberation—February 5th, to be exact—I was able to write my first real letter home in over three years. The Red Cross had made arrangements for forwarding these letters and also furnished the stationery, which was welcome.”

On paper, it sounded almost bland.

In practice, it was like being told you’d been given a new heartbeat.

He shuffled forward with the others, feeling the light weight of the paper before he saw it.

Thin, cheap stock. Lines already ruled on it.

He’d read Scripture on finer stuff. He’d written sermons on better. But this…this was holy.

He took a page. The corners of his fingers had gone numb months before, nerves damaged by deficiencies. He had to focus to grip the stub of pencil they handed him.

Around him, men hunched over makeshift tables, over bunks, over their own knees. Some could barely hold the pencil. Some could only dictate, their voices cracking as they tried to compress three years into sentences.

He stared at the blank page for a long time.

The noise around him faded.

For three years, all his written words had passed through enemy hands. He’d learned to speak in a code and pretend it wasn’t one.

We are comfortable.

When they were starving.

Conditions are good.

When men died from a scratch on the foot turning gangrenous, and there wasn’t enough medicine to numb the pain, let alone cure it.

Now, suddenly, the muzzle was off his mouth.

He could write what he wanted.

Or could he?

He thought of Rosella at the kitchen table, perhaps opening a telegram right around now, the one the Navy would have sent.

“Your husband, Lieutenant (jg) Earl Ray Brewster, previously reported a prisoner of war, has been rescued by our forces and returned to military control. His condition is reported as fair.”

The word “fair” covered a multitude of sins.

How did you tell your wife you’d buried men every day? That you’d watched men go blind slowly, faces going blank as their eyes stopped working, and had read to them by lantern until midnight so they’d have something in their heads besides darkness?

How did you confess that you’d sometimes envied the ones who went early instead of lingering?

He put pencil to paper.

His hand shook.

He wrote:

Precious people, this is a great day when I can write as a free man without censorship except as to information of a military nature.

He stopped.

The words looked strange on the page.

Free man.

He wasn’t technically free yet. He was still inside Bilibid’s walls. Still under guard, even if the guards now wore khaki and spoke English.

But he had air in his lungs and paper under his hand and no one reading over his shoulder to scratch out phrases they didn’t like.

He wrote about practicalities. That he was alive. That he expected, God willing, to see them soon. That he had been very sick but was gaining strength.

He did not describe his weight. Or his legs, still swollen from beriberi. Or the funerals interrupted by air raid sirens.

He tried to explain, saving his wife from the worst but not sugarcoating it into something pretty.

He knew she was stronger than that.

He admitted that in the first hours after liberation, he’d been too excited to “light anywhere,” too stirred up to string coherent sentences together.

He scratched out a line and rewrote it more simply.

You didn’t need eloquence when the biggest message was embedded in the mere act of putting pen to paper.

He signed it with a hand that cramped before the end.

His name looked odd. He’d written it on so many censored cards, but this time it rang differently.

This time, it was his.

Around him, other men finished their letters.

A Marine from Iowa leaned back, eyes wet. “What’d you write?” his bunkmate asked.

“‘Mom, I’m alive,’” the Marine said. “Ran out of poetry after that.”

A thin Army private who’d last seen his wife when their baby was three weeks old whispered, “I wrote, ‘Tell Tommy his daddy can’t wait to meet him.’ He’ll be three now. I hope he likes me.”

Earl folded his letter carefully.

He held it for a second, thumb pressed over his name, then handed it to the Red Cross man.

“Treat her gently, son,” he said.

The Red Cross worker looked at the emaciated chaplain and tried not to let the way his throat tightened show.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “We will.”

7. The Telegram and the Kitchen Table

On the other side of the world, in a small town in Oklahoma, a knock sounded on a door that had seen too much waiting.

Rosella wiped flour off her hands on her apron and braced herself before she opened.

A man stood there in a dark suit with a brimmed hat. He carried a telegram.

For three years, every time she’d seen a Western Union envelope, her heart had seized. She’d seen friends get them. Seen wives go pale and sit down hard on porch steps while someone else read words that began, “The Secretary of War regrets…”

This time, the man smiled.

“It’s good news, Mrs. Brewster,” he said quickly, seeing the blood drain from her face. “Your husband’s been found.”

Her hands shook as she took the paper.

YOUR HUSBAND LIEUTENANT (JG) EARL R BREWSTER US NR LAST REPORTED A PRISONER OF WAR HAS BEEN RESCUED BY OUR FORCES AND RETURNED TO MILITARY CONTROL HIS CONDITION IS REPORTED AS FAIR.

She read it twice, lips moving.

“Fair” could mean anything from “standing tall” to “still breathing but barely.”

But it didn’t say “regrets to inform you of his death.”

She exhaled shakily and thanked the man.

Days later, a letter arrived.

The envelope was worn by travel. The handwriting sloped more unevenly than she remembered, the lines less steady.

When she saw his familiar loops and flourishes, something inside her that had been clenched for years eased.

She read the first line—Precious people, this is a great day…—and began to cry, right there at the table, the children crowding close.

“Is it Daddy?” the oldest asked.

“Yes,” she said, voice breaking. “Yes. He’s coming home.”

She read the letter aloud, skipping some of the parts where his words wavered, emphasizing the hope in his phrasing.

Later, when the children were in bed and the house was quiet, she read it again, tracing the indentations where his pencil had pressed harder on certain words.

There were things he hadn’t said, she knew. Things he couldn’t yet. That was all right.

He was alive. She could wait for the rest.

8. The Bronze Star Nobody Saw

When the war ended, the Navy wanted stories.

Stories of courage. Of sacrifice. Of men who’d done their duty under fire.

They had plenty to choose from.

Pilots who’d landed burning planes on carriers. Corpsmen who’d thrown themselves over wounded Marines. Sailors who’d manned guns on sinking ships until the water closed over their heads.

It would have been easy to overlook a chaplain who never fired a shot.

They didn’t.

Word of Earl’s conduct in the camps had filtered back through survivor interviews. Men from Cabanatuan, from Davao, from Bilibid mentioned him in their debriefings.

“Chaplain Brewster?” they’d say when the Navy officer across the table asked if anyone had particularly distinguished themselves. “Yeah. He…he kept us sane. Buried our dead. Read to us at night when we couldn’t see. Always the last one to take his rice. Gave away his blanket more than once.”

The official citation was dry.

“For heroic achievement while interned as a prisoner of war, displaying great courage and unselfishness despite starvation and illness. He conducted countless religious services, ministered tirelessly to the sick and dying, and performed numerous acts of kindness that greatly improved the morale of his fellow prisoners.”

They pinned the Bronze Star Medal on his chest on a stateside parade ground, the wind tugging at the flag overhead.

He stood at attention, uniform hanging a little loose, weight still not quite back, hair thinner than it had been before the war.

He felt faintly ridiculous.

All his real work had been done in a place where no one conducted parades and the only salutes he’d gotten had been slaps on the back from men on their way to work details.

Afterwards, a young ensign shook his hand.

“Congratulations, sir,” the ensign said. “We, uh…we studied what you did. In Chaplain School. They told us about Davao.”

“Oh?” Earl said, startled. “What did they say?”

“That you…refused to let them shut you up,” the ensign said, cheeks coloring. “That’s what stuck with me, sir. That you kept reading to guys who couldn’t see. That you kept helping them write letters even when you knew the Nips would never mail ’em. That’s…why I signed up, I guess. Figured if they could be chaplains like that, maybe I could try.”

Earl didn’t quite know what to do with that.

He wasn’t a hero in his own mind.

He was a man who’d been given a job—feed my sheep—and had tried, in a place where the grass was sparse and wolves thick.

He smiled, shook the young man’s hand, and thought of the nights in Bilibid when his voice had given out but the men had asked for “just one more chapter, Chaplain.”

If the Navy wanted to make a lesson out of it, fine.

He knew the real monuments weren’t medals or paragraphs in training manuals.

They were the men who’d walked under barbed wire and out into sunlight and gone on to live lives with wives and kids and jobs and laughter.

The ones who’d written letters from hospital cots and gotten answers back.

The ones who’d sat in dim barracks listening to a thin man from Oklahoma read words about valleys and shadows and fear, and had held on for one more day.

9. Behind Barbed Wire, Ahead of Time

In the years after the war, in the quiet hum of peacetime America, Earl Brewster did not become a celebrity.

He went back to preaching in churches where the biggest crisis was a leaky roof or a squabble over the color of the new carpet.

He learned to live with the memories.

Sometimes, when he stood in the pulpit on a Sunday morning, sunlight slanting through stained glass, he’d glance up at the rafters and, for a split second, see the bamboo beams of a Davao barracks, smoke curling from a rough lantern.

On certain dates—February 5th among them—he’d take out copies of the letters he’d written in those days and read them again.

He marveled at his own handwriting.

At how small and cramped it had become, how careful.

At the way his sentences circled around the worst of it without quite touching.

He stayed in touch with some of the men he’d been imprisoned with.

They wrote at Christmas, at Easter, on the anniversaries of liberation.

Sometimes they’d come sit in his parsonage kitchen, mugs of coffee in their big hands, and talk about everything but the camps. Farming. Politics. The price of gas.

Then, after an hour or two, one of them would say, “You remember that night at Davao when mail finally came in?”

They’d go quiet, then laugh, shaking their heads.

“Bunch of grown men crowding around one envelope like kids at a candy store,” one would say. “I can still hear you reading it out, Chaplain. I could see my Mary’s handwriting in my mind while you was reading your Rosella’s.”

“Those letters kept us alive,” another would add.

“Those letters, and your stubborn voice,” a third would say.

He’d shrug. Change the subject.

He knew the truth, though.

Behind barbed wire, he’d discovered that a man’s soul can be starved by silence as surely as his body can by hunger.

By reading, by helping others write, by slipping words past the fences on scraps of paper or in memories, he’d been waging his own quiet war.

Not with bullets.

With sentences.

He’d refused to let the Japanese censor have the last say on what passed between a husband and his wife, between a father and his children, between a man and his God.

Even when the mail bags never moved, even when the Red Cross couldn’t get through, the act itself had mattered.

A man who can tell his own story, even to a piece of paper that may never leave his hands, is not entirely a prisoner.

10. The Great Day Remembered

Years later, when younger chaplains asked him what captivity had been like, he didn’t start with the beatings or the rice or the funerals.

He started with the letters.

“That day at Bilibid,” he’d say, “February 5th. That was one of the holiest days I ever saw.”

They’d frown. “The day you got out?”

“No,” he’d say. “The day we got to write.”

He’d describe the Red Cross man, nervous and earnest. He’d describe the way men’s hands had shaken as they took the paper.

“How many guys wrote deathbed letters, sir?” one young chaplain asked once. “You know…just in case?”

“Plenty,” Earl said. “And some of those letters got sent as-is. No edits. No corrections. No second drafts.”

He’d pause, remembering the gaunt faces bent over pages in the dusty light.

“But most of them,” he’d add, “were letters about life. About kids they hoped to see again. About houses they wanted to fix up. About dogs on front porches and Sundays in church and fishing trips and all the thousand little things that make up a man’s real world.”

He’d look the young chaplain in the eye.

“That’s what you fight for,” he’d say. “Not flags. Not headlines. Not parades. For the right of a man to sit at his kitchen table and read a letter from someone he loves without nobody telling him what it’s supposed to say.”

He’d smile, remembering.

“We’d had all kinds of things taken from us,” he’d conclude. “Our freedom. Our health. Our privacy. But that day…that day I got something back that the barbed wire hadn’t managed to kill.”

On February 5th, 1945, in a prison in Manila, a thin chaplain from Oklahoma sat on a bunk, pencil in hand, heart hammering, and wrote the words he’d been holding in his chest for three years.

On some other February day, perhaps decades later, Rosella would pull that letter from a box in the closet, unfold it carefully, and read it again, tracing the lines with fingers that had weathered their own share of waiting.

In the quiet between one war and the next, the story of Earl Ray Brewster would mostly be told in small rooms.

In chaplain training classes at Norfolk. In Sunday school lessons in Sacred Heart. In the living rooms of men who’d once lain on bamboo slats and listened to his tired voice read from a thin, tattered book.

It wouldn’t top history books.

It wouldn’t be taught in basic training alongside the tactics of Normandy or the island campaigns.

But somewhere, in footnotes and in memories, there would always be that picture:

A man behind barbed wire, too sick to carry a rifle, too stubborn to shut up, choosing to wield hope instead.

A chaplain who refused to let silence win, who believed that even in a prison camp, even under the watchful eye of a censor, the human heart still had the right to speak.

And on a day when the planes overhead finally belonged to his side again, when the guards’ shouts were replaced by the rumble of American tanks, when the smell of disinfectant and lime couldn’t quite cover the scent of long-delayed freedom, that chaplain picked up a pen and did the most dangerous thing he’d done in three years.

He told the truth.

He signed his name.

He sent his words out past the wire.

Behind barbed wire, beyond barbed wire, he had never truly been silenced.

THE END

News

CH2 – American POW Camps Turned This German Colonel into a Champion of Freedom

The first time Colonel Wilhelm Krauss saw an American up close, the kid couldn’t have been more than twenty. Freckles….

CH2 – A British Scout Rescues a Polish Girl from Smoke, Refusing to Leave Her Behind in Danger

On April 29th, 1945, northern Germany burned. The fire didn’t rage in a single place—it smoldered in tree lines…

CH2 – The “Texas Farmer” Who Destroyed 258 German Tanks in 81 Days — All With the Same 4-Man Crew

The sun came up over Normandy like it had seen too much and was thinking about quitting. July 16,…

CH2 – They Mocked His ‘Throwing Knife’ — Until He Dropped 8 Guards Without a Sound

At 2:15 a.m. on March 18, 1945, the world had narrowed to forty yards of frozen German dirt and the…

CH2 – How One Farmer’s Crazy Trick Defeated 505 Soviets in Just 100 Days

On December 21st, 1939, the cold had teeth. Minus forty Celsius turned every breath into glass and every exposed…

CH2 – How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Saved 4,200 Men From U-Boats

March 17, 1943 North Atlantic, 400 miles south of Iceland The sea was trying to kill them. Fifteen-foot swells…

End of content

No more pages to load