Part 1

The wind had teeth that morning.

It cut across the courtyard of St. Andrew’s Chapel, rattling the iron gates and tossing dead leaves across the path like confetti at a celebration no one attended. I stood there alone, one hand gripping the handle of my black umbrella, the other clutching a handkerchief that didn’t yet have a purpose. The hearse was already gone, the pallbearers dispersing, and I was left staring at the polished mahogany coffin inside the chapel—its brass handles gleaming under the weak light as if mocking the emptiness around it.

Only me.

Not our son. Not our daughter. Not a single grandchild.

Just me—May Holloway, eighty years old, widow of George Holloway, standing in a sea of empty pews and hollow echoes.

The funeral director shifted uneasily near the door. He was a thin, balding man who looked like he’d rather be anywhere else than facing an old woman mourning alone. His name tag read M. Connor, and he cleared his throat twice before daring to speak.

“Would you like us to wait a few more minutes, Mrs. Holloway?” he asked, voice low, almost apologetic.

“No,” I said. “Start.”

He hesitated. “Perhaps—”

“Start,” I repeated, my voice sharper than I intended. “George would have hated a delay. He was punctual even in death.”

Connor gave a small nod and gestured to the pastor, a weary man in a gray cassock who looked like he’d lost faith years ago but still remembered the motions. He opened his Bible, began to speak words that should have sounded holy but landed flat against the cold air.

I sat in the front pew, the first of five chairs set aside for family. All five were empty except for mine.

The flowers—white lilies and red roses—were too bright against the muted light. The casket gleamed too clean, as if even grief had been polished out of it. I folded my hands in my lap and listened to the pastor recite scripture with the precision of someone reading a manual. I wondered if George could hear it wherever he was, and if he’d shake his head and grumble, “They don’t make sermons like they used to.”

He’d been a man of routine, my George. Punctual, deliberate, proud. He took his pills by the clock, watched the evening news at six sharp, and folded his slippers side by side before bed. He lived his life like a metronome, steady and sure.

And now, he was being buried alone.

I stared at the coffin as if I could see him inside. Not the frail man in the hospice bed, not the pale face framed by hospital white, but the younger George—the man who built our porch with his bare hands and danced with me on it the night it was finished, barefoot and laughing, the radio humming some forgotten tune.

He’d built so much—our house, our life, even the sense of order I’d been living on like oxygen. And now all of it felt like a cruel joke. The man who kept the world spinning was gone, and the people who should’ve been here to honor him were too busy pretending to live.

Our son Peter had texted that morning. Just one line:

Sorry, Mom. Something came up. Can’t make it.

No call. No explanation. Just absence disguised as busyness.

And Celia, our daughter, hadn’t even bothered with that. She’d left a voicemail two days earlier, all air and sunshine:

“Mom, I really can’t cancel my nail appointment, and you know how anxious I get with reschedules. Tell Dad I’ll visit him next week.”

Next week.

As if dead men waited.

The pastor’s voice rose faintly, “…for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.”

I looked around. The rows of pews were empty except for two funeral staff standing awkwardly at the back. Even the weather seemed to hurry past. Outside, wind howled against the stained glass, scattering petals from a wreath someone had sent—someone from George’s old office, probably, who had written Our condolences on a card and gone back to lunch.

When the final amen came, I didn’t cry. Not because I wasn’t grieving, but because the grief had already hollowed me out long before that day. There’s a kind of sorrow that doesn’t break you; it buries you alive.

The pastor gave a gentle nod. “Would you like a few moments alone, Mrs. Holloway?”

I rose carefully, my knees aching as I stepped toward the casket. “No,” I said. “We’ll proceed to the burial.”

The pallbearers—four young men I didn’t know—carried the coffin out. I followed, my heels sinking into the wet grass as we crossed the courtyard. The sky hung low and gray, swollen with unspent rain. Somewhere in the distance, I heard a church bell toll once, then fade.

At the cemetery, a single groundskeeper watched from afar, leaning on a spade. The hole was already dug, the earth dark and heavy at its edges. The coffin was lowered slowly, the ropes squeaking faintly, until it rested in the dirt. The pastor mumbled another prayer, shorter this time. No one said goodbye. No one tossed a flower.

“Rest well, George,” I whispered. The words felt small against the wind.

When the last clod of earth fell, I stood alone for a long time. My hands trembled against my coat pockets. My breath came in soft white clouds. I could almost hear George teasing me for standing too long in the cold.

Then, for the first time since he died, I let myself speak to the empty air.

“You deserved better,” I said quietly. “But I’ll make it right. Somehow.”

Back home, the silence hit harder than the wind ever could.

The house was just as we’d left it: the recliner untouched, the slippers side by side, the TV remote where he’d last placed it.

I set my purse down and sank into the chair opposite his. The cushion had molded to his shape over the years, and the faint smell of aftershave still lingered. On the mantle, our 40th anniversary photo smiled down at me—George in his best suit, me in the rose-colored dress he loved.

I poured myself a glass of wine—red, the expensive kind I used to save for guests—and stared at the photo. Then, almost against my better judgment, I reached for my phone.

Celia’s Instagram.

The first post that came up was from two hours ago:

Celia and her friends, glasses raised high, laughter frozen midair.

Caption: Girls brunch! Bottomless mimosas, living our best lives!

Then Peter’s feed:

A golf course. Bright sun, green fairway, new driver.

Caption: Killer swing. Perfect weather. Deals made.

Deals made.

While their father’s coffin was lowered into the ground.

I stared until the screen blurred. Then I set the phone down and whispered to no one, “He would’ve asked where the hell you were.”

The next morning, I woke to a silence that felt heavier. I made coffee but didn’t drink it. I walked past his chair and straight to the hall closet where we kept the files—everything George insisted on organizing.

The folder labeled Estate sat at the back, neatly tied with a rubber band. I placed it on the kitchen table and opened it slowly. Inside: copies of our will, the deed to the house, bank accounts, investment summaries. George had labeled each section in his steady hand.

Peter and Celia were listed as beneficiaries to everything—our savings, the house, even the lake cabin they never visited but always complained about paying taxes for.

I stared at the ink until the letters blurred. Something inside me began to tighten—not grief this time, not quite anger either. Something colder. Clearer.

The words formed in my mind with sharp precision:

They don’t deserve it.

Not after today. Not after all the years I spent cushioning their falls, writing checks they never thanked me for, listening to promises they never kept.

The house was still, the clock ticking faintly in the background. George’s voice echoed in memory: Legacy isn’t what you leave—it’s who you leave it to.

Maybe it was time I finally understood what that meant.

That afternoon, I dialed a number I hadn’t used in months.

“Thomas Fields’ office,” came the receptionist’s crisp voice.

“Tell him May Holloway needs an appointment,” I said. “Today, if possible.”

“Mrs. Holloway,” she said kindly, “I’ll see if he can fit you in. Is it urgent?”

I looked at George’s empty chair, the framed photo, the folded slippers.

“Yes,” I said. “It’s urgent.”

Part 2

Thomas Fields’ office hadn’t changed in thirty years.

The same mahogany shelves lined with law books no one opened anymore, the same faint scent of eucalyptus polish and old paper, the same steady tick of the brass clock behind his desk.

It was the kind of place where time felt thick, and silence carried weight.

“May,” Thomas said when I walked in. He rose from behind his desk, smoothing his tie with the habitual care of a man who respected precision. His hair had gone mostly white, but his eyes were still sharp. “You’re early.”

“It couldn’t wait,” I said. My coat was still damp from the drizzle outside. “George would’ve scolded me if I showed up late to my own decision.”

He smiled faintly. “I got your message. You said you needed to revise your will?”

“Yes.” I sat, folding my hands on the desk. My fingers were cold, but my resolve was warm. “I want to remove Peter and Celia entirely.”

He didn’t blink. That was one of the reasons I liked him—he never gasped or moralized. He only adjusted his glasses, a small tilt of thought. “Are you certain, May?”

“I buried my husband alone,” I said, my voice steady. “Our children didn’t come. Not a call, not a flower. They were busy.”

He nodded once, slowly. “Then let’s make it official.”

He pulled a yellow legal pad closer and began writing in his precise, looping script.

We discussed details. Accounts. Properties. The lake cabin. The trust funds. Each time he asked a question—‘Do you wish to redirect this?’, ‘Shall we include the annuity?’—my answer came clear.

“Yes.”

“Yes.”

“All of it.”

Thomas looked up after a few minutes. “Do you want to name an alternate beneficiary?”

I hesitated. Then a face came to mind—not Peter’s self-satisfied grin or Celia’s manicured smile, but Ethan’s, Celia’s boy. My grandson.

The only one who’d ever come by without asking for something.

The boy who mowed my lawn last summer, sweating under the July sun, just because he said, “You shouldn’t be out here, Grandma.”

The one who’d brought me books from the library and actually wanted to talk about them.

I took a breath. “Yes. Ethan.”

Thomas’s pen paused. “You’d like to leave your estate to him?”

“I’d like to establish a trust,” I said. “Everything goes to Ethan. The house, the cabin, the savings. I want it protected—from his parents, from anyone who’d try to get a hand on it.”

He nodded approvingly. “An irrevocable trust, then. He’ll have controlled access until he’s thirty, unless for education or health expenses.”

“That sounds right.”

He smiled faintly, the kind of smile only lawyers who’ve seen too many ugly families can manage. “You’re handling this cleaner than most people your age, May. Most want to forgive.”

“I’ve forgiven,” I said. “But forgiveness doesn’t mean reward.”

He tapped his pen once against the pad. “Understood.”

For the next hour, we reviewed every clause. The room filled with the scratch of his pen, the whisper of turning pages, the low hum of the heater. When he finally slid the papers toward me, I read each line carefully. I wasn’t signing out of anger. I was signing out of clarity.

When we finished, he sat back. “May,” he said gently, “I’ve known you a long time. This isn’t just paperwork, is it?”

“No,” I said. “It’s pruning.”

He raised an eyebrow. “Pruning?”

“When a rosebush grows wild,” I said, “you have to cut away the parts that choke the rest. Doesn’t mean you hate the plant. You just want it to live again.”

He studied me for a long moment, then nodded. “Then we’ll file it this afternoon.”

Outside, the October air had a bite. The sky was pale blue, the kind of color that looks thin against cold. I walked slowly to my car, each step echoing faintly on the sidewalk. Across the street, a young mother pushed a stroller, her scarf fluttering behind her like a bright banner of life. I didn’t envy her. I just noticed her. Like a song I used to love but didn’t need anymore.

When I reached home, the house greeted me with its usual stillness. I hung my coat, set my purse down, and sat by the window. The garden was losing its color; the roses had begun to brown at the edges. I’d always meant to trim them, but George had liked letting them fade naturally.

“They surrender with dignity,” he used to say.

I looked at them now, shriveled and bowing under their own weight. “So did you,” I whispered.

That night, I didn’t pour wine. I made tea—real tea, loose leaves steeped in a ceramic pot George bought for me on our tenth anniversary. I sat at the kitchen table with the will papers still fresh in their envelope, the ink barely dry.

It wasn’t satisfaction I felt. It wasn’t even relief.

It was space—like a crowded room had finally emptied.

The phone rang two days later.

Unknown number. I nearly didn’t answer.

“Grandma?” The voice was tentative, male, young.

“Ethan?”

“Yeah. Hey.” He paused. I heard background noise—a car, maybe a bus. “I just heard about Grandpa. Mom didn’t tell me until yesterday.”

My throat tightened. “He’s been gone nearly three weeks.”

“I know,” he said, guilt heavy in his tone. “I’m sorry, Grandma. I would’ve come.”

I closed my eyes. “I know you would have.”

“Can I come by? I just—I want to see you.”

“Of course.”

He arrived an hour later, taller than I remembered, all long limbs and awkward grace. His hair was messy, his eyes red from the cold. He hugged me hesitantly, the way young men do when they’re not sure if affection is still allowed.

I didn’t hesitate. I held him tight.

“I’m sorry,” he said again. “Mom said everything was handled.”

I pulled back. “Your mother thought funerals were optional.”

He looked at me, shame flickering across his face. “She said she was busy—”

“She was at brunch,” I said flatly.

He winced. “I saw the post.”

We sat at the table. I poured lemonade. He stared at his hands, fidgeting with the condensation on the glass.

“I want to do something,” he said suddenly. “For him. For you. Anything.”

“You already are,” I said. “You’re here.”

He didn’t seem convinced. I hesitated, then rose and retrieved the envelope from the sideboard—the one Thomas had given me. It was still sealed.

“I was going to take this to the bank tomorrow,” I said, setting it in front of him. “But I want you to see it first.”

He frowned, picking it up. “What is it?”

“My new will.”

He blinked. “You changed it?”

“Yes.”

He started to open it, then hesitated. “Why are you showing me this?”

“Because it’s yours.”

He froze. “Mine?”

I nodded. “Everything. The house, the cabin, the savings. It’s all going to you.”

He stared at the envelope like it was made of glass. “Grandma… why me? Why not Mom or Uncle Peter?”

“Because,” I said softly, “you’re the only one who came back without being asked.”

He swallowed hard, his eyes wet. “I don’t know what to say.”

“You don’t have to say anything,” I said. “Just remember who you are. And remember what love looks like when it’s real.”

He nodded, tears slipping down his cheek. Then, almost whispering, “Can I come next weekend?”

“Of course.”

He smiled, small but genuine. “Can we make pancakes again?”

I laughed softly. “We’ll even use the good syrup.”

When he left, the house didn’t feel quite as empty.

For the first time since George’s death, the silence wasn’t heavy—it was gentle.

But peace doesn’t last long when family catches the scent of lost money.

The next morning, the crunch of tires on gravel broke the quiet. I looked out the window and saw Celia’s SUV parked crooked in the driveway, its glossy black hood gleaming like armor. She didn’t knock. She just walked in, heels clicking, perfume first.

“Mom,” she said, dropping her handbag on the hall table. “We need to talk.”

I didn’t look up. I was folding laundry—slow, deliberate, one sock at a time.

“I’ve been trying to reach you,” she said. “You haven’t answered.”

“I’ve been busy.”

“Busy with what?”

I folded another towel. “Peace.”

She sighed dramatically. “Ethan told me you’re changing your will. Please tell me that’s not true.”

I looked up. “It’s true.”

She blinked. “You’re removing Peter and me? After everything we’ve done for you?”

I set the towel down. “What have you done for me, Celia?”

She scoffed. “I don’t know—kept in touch, helped when Dad was sick—”

“You didn’t visit him once,” I said quietly. “Not once.”

Her jaw tightened. “I sent flowers.”

“To the hospital,” I said. “Not the funeral.”

She opened her mouth, closed it again. Her hands trembled on the countertop. “You’re punishing us.”

“No,” I said softly. “I’m freeing myself.”

She laughed bitterly. “You think leaving everything to a college kid is freedom? He doesn’t know the first thing about money.”

“He knows how to show up.”

Her mouth opened again, but nothing came out. For a moment, she looked small—just a girl again, cornered by truth. Then she grabbed her handbag.

“I hope this makes you feel powerful,” she said.

“No,” I replied. “It makes me feel peaceful.”

She left without another word.

That evening, I found a note on the doorstep.

No envelope, just paper, creased and smudged.

You don’t understand what it’s like to balance everything. We tried our best. Maybe we failed. But cutting us out isn’t the answer.

I folded it neatly and placed it in the drawer labeled Miscellaneous.

Because that’s what it was now—just another scrap of noise.

Part 3

The doorbell rang the next morning.

Not a polite chime, but a firm, insistent ring—like someone trying to remind the house of its own heartbeat.

I already knew who it was.

Through the frosted glass, I saw a tall outline, shoulders squared. Behind him, a shorter silhouette—her posture stiff, her hair a sleek helmet of control.

Peter. And Meredith.

I opened the door slowly. “Morning,” I said, voice even.

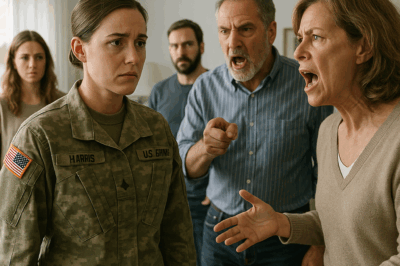

“Mom,” Peter began, his tone rehearsed, his eyes darting anywhere but my face. “Can we come in?”

I stepped aside, letting them in without a word. Meredith gave a small, perfunctory smile. She was wearing a cream coat far too elegant for a visit like this, and a diamond ring that glinted each time her fingers tightened on her purse strap.

The air between us was already thick with unspoken things.

We moved to the sitting room. They didn’t take off their coats. I didn’t offer coffee.

“I heard from Celia,” Peter said after a long silence. “And from Ethan.”

“I imagine you did.”

He cleared his throat. “I think there’s been some confusion.”

I raised an eyebrow. “About what?”

Meredith crossed her legs, perfectly. “About your will, May. We understand you’ve been under a lot of stress, and grief can—well—make people act impulsively.”

I looked at her. “You didn’t come to the funeral either.”

She blinked. “I had a client dinner. International account. You know how my schedule is.”

Peter’s eyes darted to hers, then back to me. “Mom, I should’ve called. I should’ve come. I didn’t know how to—”

“No,” I interrupted. “You didn’t want to. That’s the difference.”

He sighed heavily, rubbing the back of his neck. “Look, I know you’re upset. But you can’t just erase us, Mom. We’re your children.”

“You erased yourselves,” I said calmly. “I’m just acknowledging the fact.”

Meredith leaned forward, her voice suddenly syrup-sweet. “May, we’re not here to argue. We just want to make sure you’re protected. Changing legal documents at your age can be… risky.”

“My lawyer’s competent,” I said flatly.

“Even so,” she continued, “Ethan is young. He doesn’t understand how to manage a trust or property. He could be manipulated.”

I tilted my head. “By whom?”

Meredith smiled without humor. “By people who know he’s inherited something valuable.”

I stared at her, long enough for the silence to stretch thin. “You mean you.”

Her jaw tightened, just slightly. Peter jumped in quickly, his voice pleading. “Mom, that’s not fair.”

“No,” I said softly. “What’s not fair is standing by while your father was lowered into the ground. What’s not fair is ignoring your mother until there’s money to discuss.”

“Mom—”

“Don’t,” I said sharply. “Don’t you dare call me that like it still means something.”

He flinched. For a second, he looked twelve again—the same boy George once caught trying to hide a broken window behind a curtain, guilty but too proud to admit it.

Meredith straightened. “This could get complicated, legally.”

“It won’t,” I said. “The paperwork’s clean.”

“Mom,” Peter tried again, softer now. “I thought you forgave people.”

“I do,” I said. “But forgiveness doesn’t mean access.”

That landed like a stone between us.

He looked away first.

After a moment, Meredith rose, her smile brittle. “Thank you for your time, May.”

They walked to the door. I didn’t follow. Only when it clicked shut did I let my hands tremble. Not from fear—just release.

They would go home, call Celia, and together they’d rewrite the story. I knew that. I would become the cruel old woman who lost her mind to grief. But truth didn’t need an audience. It only needed to stand.

That evening, I sat by the window, watching the light fade over the yard. The roses were almost bare now. Winter was close. George would’ve said, They’ll bloom again.

And maybe they would.

I went to bed early that night. Slept for the first time in weeks without waking at three a.m. to count what was gone.

The next morning, I woke to a soft knock. When I opened the door, Lorraine Campbell was there—my neighbor of fifty years, holding a tin of shortbread and wearing her usual mix of curiosity and concern.

“I saw Peter’s car yesterday,” she said, stepping inside before I could invite her. “Did he bring flowers or just excuses?”

I smirked. “Neither. He brought his wife.”

“Oh, that one,” she said knowingly. “The one who thinks sympathy is a business expense.”

We sat in the living room, tea steaming between us. Lorraine placed the tin on the table but didn’t open it yet. “So,” she said, “you told them?”

“I told them.”

“And?”

“They left angry.”

“Good,” she said without hesitation. Then, softer, “About damn time, May.”

I laughed quietly. “You make it sound like a revolution.”

“It is,” she said. “I’ve watched you for years—writing checks, babysitting grandkids, bailing them out of their own messes. I kept waiting for you to stop playing the martyr.”

“I wasn’t a martyr,” I said.

“No,” she said gently. “You were a mother. That’s worse.”

I looked down at my cup, the tea swirling like smoke. “Do you think I’m cruel?”

“Cruel?” Lorraine laughed, a full-bodied sound that filled the room. “May, you’re the kindest woman I know. But you’ve been kind past the point of self-destruction. You didn’t cut them off—you finally stopped bleeding.”

I didn’t reply. She reached across the table and squeezed my hand.

“They’ll say terrible things,” she said. “They’ll paint you as heartless. Let them. You and I both know who built their safety nets—and who they let fall through them.”

I blinked hard, but the tears didn’t fall.

Sometimes, even grief runs out of water.

We talked for another hour about her garden, the squirrels that kept chewing on her gutters, and the way time has a habit of sanding down old anger into quiet acceptance. When she left, she hugged me longer than usual. I held on, because it felt like something solid in a world that kept dissolving.

Later that afternoon, I went to the bank.

The building smelled like lemon cleaner and quiet power. A young receptionist stood the moment she saw me. “Mrs. Holloway! Mr. Jansen will be right with you.”

Mr. Jansen—Richard—had handled our accounts for decades. Impeccable suits, polished manners, and a loyalty to confidentiality that would make a priest jealous. He greeted me warmly and led me into his glass-walled office.

“I was surprised by your message,” he said, settling behind his desk.

“Good,” I said. “Surprise is healthy.”

He smiled, uncertain whether I was joking. “I understand you’ve made some estate changes?”

“Yes,” I said, sliding the folder across the desk. “And I want to ensure they’re carried out immediately.”

He opened it, his brows lifting as he read. “You’ve revoked all linked transfers to your children and established a trust in your grandson’s name. That’s… a significant adjustment.”

“I’m a significant woman.”

He chuckled. “Indeed you are.” Then, more serious: “Do you want any safeguards? To prevent interference?”

“Yes. Ironclad. No appeals, no family representatives twisting his arm five years from now.”

“We can structure that. Disbursements only for education, housing, or medical needs until he’s thirty. Then full access.”

“That’s perfect.”

He glanced up at me. “You understand this can’t be undone easily.”

“I don’t want it undone.”

He nodded, signing a few internal forms. Then he leaned back, studying me. “May, forgive my bluntness—but are you doing this out of anger?”

I thought about that for a long moment. The chapel. The empty chairs. The golf post. The mimosa glasses raised to the sky.

“No,” I said finally. “I’m doing it out of clarity.”

He smiled, almost wistfully. “That’s rare.”

“Not rare,” I said. “Just late.”

When I stepped back outside, the afternoon sunlight hit different. Not brighter, exactly—but cleaner. Like it had stopped filtering through grief.

Across the street, a little café I hadn’t been to in years sat with its door propped open, cinnamon in the air. George and I used to go there after errands. On impulse, I crossed over, ordered a cappuccino, and sat by the window.

The first sip burned a little. The kind of burn that wakes you up.

Outside, life moved on—people walking, buses sighing, a boy carrying a bouquet of flowers that weren’t for me but could’ve been once. I watched them all pass, feeling the quiet satisfaction of someone who’s finally done waiting for permission to breathe.

That night, I pulled out an old letter George had written to me from his first business trip, yellowed and folded neatly.

May, this house is never empty with you in it. You are the roof, the floorboards, and the lock on the door. Even when it feels like no one sees you, I do.

I read it three times before tucking it back into the drawer.

The house wasn’t empty anymore.

It was just… mine again.

Part 4

The envelope came three days later.

It was thin, plain, the kind of thing that usually carried bills or political flyers. But the handwriting stopped me cold.

Careful block letters, slightly slanted, pressed too hard into the paper — Ethan’s handwriting.

I set the mail pile on the counter, made tea, and let the envelope sit while the kettle whistled.

When the steam settled, I carried the cup and envelope to the kitchen table, sat down, and stared at it for a long time.

It had been years since someone had written me a real letter.

Finally, I tore it open.

Dear Grandma,

I wanted to write this instead of texting. I could’ve just said it last time I saw you, but I didn’t have the right words.

Now I know there aren’t perfect words, so here are the honest ones.Thank you.

Not just for the trust, or the house, or the money — though I know what a big thing that is — but for being the only person in this family who never asked me to be anything but myself.You’ve always made space for me. When Mom told me to be more polished, more ambitious, you just asked me what book I was reading.

I didn’t know Grandpa was sick. I didn’t know he died. I would’ve been there. I swear I would’ve. I’m angry at Mom for not telling me, but I’m angrier at myself for not calling sooner.

I don’t know why you chose me, but I promise I won’t waste it. I want to take care of this house. I want to learn what you and Grandpa built. I want to understand the kind of strength it takes to keep showing up when no one else does.

I love you, Grandma.

I don’t say it enough, but I do.— Ethan

I read it once dry-eyed, once with my hand over my chest, and once through tears that blurred the ink.

Then I set it on the mantel, beside George’s photo, and whispered, “You were right, love. Legacy isn’t what you leave — it’s who you leave it to.”

That night, I sat in George’s chair. The silence felt softer. The house didn’t echo anymore; it hummed — like it was alive again, waiting for footsteps, conversation, laughter.

A week passed before another knock came at the door.

Not brisk like Celia’s. Not hesitant like Ethan’s.

This one was… reluctant.

When I opened it, Meredith stood there alone, a store-bought pie in her hands.

“Apple,” she said quietly.

“Come in,” I said, more curious than kind.

She stepped inside like someone entering a stranger’s home — eyes scanning everything, lingering on the coat rack George had built decades ago. The same one Peter broke a peg off as a kid. George never fixed it. “It’s part of the story now,” he used to say.

We ended up in the kitchen. She placed the pie on the counter and clasped her hands. I didn’t offer tea.

“I didn’t come to ask for anything,” she said.

“Good.”

She exhaled slowly. “I heard what happened. About the trust. The will.”

I nodded once. “You probably heard correctly.”

“I wanted to say thank you.”

That startled me. “For what?”

“For not giving it to Peter.”

I blinked. “Excuse me?”

She met my eyes for the first time, and to my surprise, there was no coldness there — just exhaustion. “Peter never learned how to stand on his own. I tried to keep the illusion up, but we both know I didn’t help. You enabling it didn’t help either. But now…” She looked down at her hands. “Now it’s just who he is.”

I said nothing. There was nothing to say.

“He blames you,” she continued softly. “Celia does too. But what they don’t admit is that you held the whole family together for decades while they complained about how you did it.”

“Why are you telling me this now?” I asked.

“Because I’m tired, too.”

The quiet that followed wasn’t awkward. It was honest — two women who had both spent years pretending exhaustion was grace.

She finally sat, her voice shaking. “I admired George. He was kind to me, even when he didn’t have a reason to be. And I never thanked you — for everything. The help. The money. The babysitting. The constant yes.”

“You didn’t owe me thanks,” I said. Then, after a pause, “You owed him your presence when he left this world. You both did.”

She lowered her head. “I know.”

There was no triumph in saying it. Just truth, brushed clean of emotion.

She reached into her purse and pulled out a small photo. A little boy on a swing — Ethan, maybe five years old, cheeks round, smile huge.

She slid it across the table. “He loves you,” she said. “You know that, right?”

“I do.”

She smiled faintly. “I hope he loves someone one day the way he loves you. And I hope he knows how rare it is.”

She stood, straightened her coat. “I won’t keep you, May. I just wanted to say that before they rewrite the story — before they turn you into the villain in their version.”

The wind caught her scarf as she opened the door. She paused, looking smaller now, younger somehow. “Don’t let them take your peace, May,” she said. “They’ve taken enough.”

When she was gone, I stood there for a long time, watching the curtains sway in the breeze.

Then I picked up the pie and put it in the fridge.

Not out of sentiment — just because it would be good with tea tomorrow.

The letter from the attorney came a week later.

Not an emergency. Just confirmation.

The new documents were filed.

The trust was active.

Ethan’s name now lived where Peter and Celia’s used to be.

It felt quiet, not victorious — like the world had finally caught up to a decision my soul had already made.

I carried the letter into the garden.

The roses had withered completely now — dry, brown, fragile. George used to call it “surrendering with dignity.”

I understood him better than ever.

I sat on the bench he’d built and ran my fingers along the envelope. The garden was empty, the air cold but not cruel. There’s a difference. Cruel cold bites. Honest cold just tells the truth.

I whispered, “It’s done, George. It’s really done.”

The wind moved through the dead leaves like an exhale.

That afternoon, I decided to do something small but symbolic — something that wasn’t about death or legacy or closure.

I pulled the old sewing machine out of storage. The one I hadn’t used since before George got sick. I oiled the wheel, threaded the bobbin, and listened to its soft hum come back to life.

I didn’t plan anything big. Just new kitchen curtains — bright blue, with clumsy white stitching that wouldn’t match a single thing in the house.

But they were mine.

When I hung them up, sunlight caught the uneven threads and made them glow like veins of light. The house suddenly looked less like a museum of memories and more like a place that still had a future.

That evening, I wrote a short letter to myself and tucked it into George’s old desk drawer.

You are not invisible.

You are not cruel.

You are not required to earn peace by breaking yourself in half.

You can rest now.

The next morning, Ethan arrived again — right on time, with a bag of groceries and that awkward grin that always reminded me of George’s patience.

“Brought you some fresh stuff,” he said, unloading apples and eggs onto the counter. “You, uh… feel like making pancakes?”

I smiled. “You remembered.”

“Course I did.”

We cooked together. He listened as I showed him how to test the pan’s heat with a drop of water, how to fold the batter without losing air, how to flip them without tearing. He didn’t rush. He didn’t scroll through his phone. He just listened.

When we sat down to eat, he took a bite and grinned. “You’re really good at this.”

“I’ve had time to practice.”

He swallowed another forkful. “You know, Grandma, I’ve been thinking. Maybe I’ll fix up this house a bit. Start with the porch. It’s leaning.”

“You’ll need real tools,” I said. “Not those plastic ones from college starter kits.”

He laughed. “Guess you’ll have to teach me.”

We finished breakfast in easy silence. Outside, the frost was melting on the grass. The air smelled faintly of maple syrup and something else — maybe hope.

When he left, I watched him walk down the driveway and thought, George would’ve liked him even more now.

That night, I didn’t drink wine. I didn’t reach for distractions.

I just sat in the quiet and realized that the quiet wasn’t loneliness anymore.

It was ownership.

Part 5

The first snow came quietly.

Not a storm, not even a proper snowfall — just a whisper of white dust across the yard, soft and temporary. It caught on the railings and roses, clinging for a moment before melting into the dark soil.

I stood on the porch, wrapped in George’s old cardigan, coffee warming my hands, watching it fall.

Ethan was out front, kneeling on the steps with a carpenter’s level. His breath puffed in small clouds as he muttered to himself, adjusting a railing he’d been repairing all week.

He had his grandfather’s frown of concentration — the same furrow between the brows, the same quiet determination.

It had been a month since I’d signed the papers, and the world hadn’t applauded, but something inside me had unclenched.

A space had opened — where guilt used to sit.

Ethan looked up. “Hey, Grandma, come see this!”

I stepped down carefully, boots crunching on the light frost. He beamed, showing me the porch rail — smooth, sanded, perfectly stained.

“What do you think?” he asked.

“It leans a little to the left,” I said.

He grinned. “So does everyone in this family.”

I laughed. Loud and real. The kind of laugh that comes from the stomach, not the throat. It startled me at first — I hadn’t heard that sound in years.

George would’ve loved that laugh.

Ethan stood beside me, wiping his hands on a rag. “I was thinking,” he said. “Next spring, maybe I’ll plant a garden out front. Not just flowers — vegetables, herbs. Something that grows.”

“That sounds just right,” I said.

He nodded, pleased, then added, “You could teach me. You know, how to keep them alive.”

“I can do that,” I said. “Though the trick is not overwatering. People drown things trying to keep them safe.”

He looked at me like he understood it wasn’t just about plants.

After he left that afternoon, I cleaned the kitchen. Not because it was messy — because it felt good to take care of something that stayed put when I touched it.

I opened the window, let the cold air in, and watched the new curtains sway lightly in the breeze. The scent of cinnamon from the morning’s pancakes still lingered.

I thought about George again — not the dying version, not even the husband of middle years — but the young man who used to tap my nose with flour when we baked bread in the first apartment, both of us broke, hopeful, laughing over burnt loaves.

He’d always said, “We’ll build something, even if it’s slow.”

He was right.

We did.

That evening, I set the table for one.

I roasted chicken, peeled potatoes, poured a single glass of wine. I lit a candle, even though I didn’t need to.

When I was younger, I’d have called this loneliness.

Now it felt like peace.

After dinner, I washed the dishes slowly, humming to myself. Then, on a whim, I walked to the den — George’s old space. The room still smelled faintly of tobacco and pine oil. I hadn’t touched most of it since he passed.

The record player sat in the corner, dusty, waiting. The same one he’d tried to fix a dozen times before declaring it “perfectly imperfect.”

I lifted the needle, wiped the vinyl clean, and let it spin.

A soft crackle filled the air.

Then the first bars of our favorite old song drifted through the room — “Unchained Melody.”

I smiled and, without thinking, began to dance.

Barefoot on the rug.

Slow, swaying, half a step out of rhythm, but full of something pure.

The record skipped every few seconds, but I didn’t stop. My knees complained, but I didn’t care. For a few minutes, I was twenty again. George was alive, and the world was still something we could build together.

When the song ended, I laughed softly — breathless, weightless.

Then I noticed something in the hearth: a small wicker basket full of old kindling. I hadn’t touched it since before George got sick. I knelt to clean it out, brushing away the ash and dust.

At the bottom was a folded scrap of yellow paper.

I frowned, unfolded it carefully.

George’s handwriting.

Keep dancing, May — even if it’s just in the kitchen.

The world will try to make you smaller. Don’t let it.

My breath hitched. I sat back on my heels, tears stinging my eyes. He must have written it years ago, tucked it away for me to find — the same way he used to hide little notes in my recipe books.

He had known.

Maybe not everything, but enough.

I pressed the note to my chest and whispered, “You clever man.”

For the first time in months, the ache in my chest wasn’t sorrow. It was gratitude.

The next morning, sunlight broke through the frost.

I made two cups of coffee out of habit, then smiled and poured one down the sink. Old habits fade, but kindly.

I sat by the window, watching the neighborhood wake up. The Wilsons’ porch swing still squeaked. Lorraine’s old cat stalked birds with the same doomed optimism.

The world, it seemed, hadn’t paused to grieve — it had just kept turning.

And so had I.

Around noon, I opened the file drawer labeled “Family.”

It used to hold tax forms, bank receipts, tuition transfers, all the paper proof of love spent like currency.

Now, I filled it with something new:

The letter from Ethan.

The note from George.

A copy of the new will.

And a fresh envelope, addressed only to one person.

I sat down and began to write.

Dear Ethan,

If you’re reading this, I’ve gone to join your grandfather. Don’t look sad when you read that — we had a good, long life, and we earned our rest.

You’re a good man, Ethan. I saw it long before you did. You have your grandfather’s hands and his patience — that quiet kind of strength that doesn’t need applause.

This house is yours now.

Not because I wanted to reward you, but because you were the only one who showed up when it mattered.Keep it alive. Let it breathe. Don’t turn it into a monument. Fill it with noise, with people who matter, with Sunday breakfasts and muddy shoes and the smell of something baking.

Fix what breaks, but don’t over-polish it. The cracks are part of the story.

Plant something every spring. It doesn’t have to bloom, but you should try anyway.

And when life gets loud, and people demand too much, remember this: love doesn’t keep score. But it does require showing up.

Be the one who shows up.

I love you, my boy. Always have.

— Grandma May

I sealed it, slid it into the folder, and placed it in the drawer.

Then I closed it gently, the metal groaning a little — the sound of something ending well.

That night, I took a walk.

Just down the block, no destination. The moon was bright, the air crisp. The houses glowed with warm light behind their windows — other people’s lives, steady and safe.

When I reached the corner, I turned back toward home. My home.

The curtains I’d sewn glowed faintly blue under the porch light.

For the first time since George died, I didn’t feel like a widow.

I felt like myself again.

Inside, the fireplace was clean.

The note still sat where I’d found it.

I placed it in a small frame and set it on the mantel beside the photo from our 40th anniversary.

I whispered into the quiet, “You’d be proud of him, George. And maybe a little proud of me too.”

The house creaked softly in response, the way old houses do — like wood sighing with memory.

I smiled. “I’ll take that as a yes.”

In the weeks that followed, I noticed small changes:

Ethan came by every Sunday without fail.

He fixed the squeaky cabinet door, cleaned the gutters, and started sketching plans for a garden.

Celia sent one text — Hope you’re proud of what you’ve done.

I didn’t reply.

Peter never called again.

But one evening, I looked out the window and saw Ethan crouched in the yard, planting bulbs in the cold earth. He didn’t know if they’d bloom. He planted them anyway.

That was enough.

Spring came quietly that year.

The air softened.

The curtains fluttered.

The roses began to sprout again — stubborn things, those roses, surrendering with dignity and returning with grace.

One morning, I woke to the smell of pancakes and laughter drifting up from the kitchen.

Ethan was downstairs, humming to himself, flipping batter in the pan.

“Morning, Grandma!” he called. “I hope you’re hungry.”

I smiled. “Always.”

He poured syrup — the good kind — and we ate in easy silence.

Then he looked up, grin bright. “You know, I think this place could be something. Not just a house — maybe a community garden, or a little workshop. A space for people who don’t have one.”

I felt something lift inside me — a warmth, a lightness.

“Your grandfather would’ve liked that,” I said.

“Then it’s settled,” he said. “We’ll make it happen.”

He said we.

And I knew he meant it.

That night, I sat in my chair by the window, watching the garden lights flicker outside.

The air smelled of rain and new beginnings.

I opened my last journal and wrote one final entry.

You tried longer than you should have.

You bent until you broke.

You gave until there was nothing left, and still you kept giving.But you also loved fiercely.

And that love has roots — deep enough to outlast disappointment.You are free now.

Not empty. Not forgotten.

Free.

I closed the notebook, set it on the table, and turned off the light.

Outside, the roses moved in the breeze, whispering against each other — alive again.

The house was quiet, but not silent.

It was breathing.

It was home.

THE END

News

CH2 – HOA Called 911 When I Refused To Join — I Had Proof My Property Wasn’t In Their Jurisdiction…

Part 1: The first time I met Karen Ridley, she was standing on my front lawn like she owned it….

CH2 – An Elderly Man Got 23 Parking Tickets in the Hospital… What Judge Frank Caprio Found Exposed His Son…

Part 1 The courtroom was quiet except for the soft shuffle of papers and the faint hum of the fluorescent…

CH2 – My Father Slapped Me For Saying No To His Demands — A Year Later They’re All Walking On Eggshells…

Part 1: The sound of the slap reverberated through the reception hall like a gunshot. Two hundred conversations halted mid-sentence….

CH2 – HOA Karen Called the Cops When We Refused Her HOA—Then Froze at My Wife’s CIA ID!…

Part 1: When we moved into Birch Ridge Estates, I thought we’d found paradise in suburbia. Tree-lined streets. Kids on…

CH2 – At The Family Party, My Parents Shouted: “Get Out… No One Needs You Anymore.” So I…

Part 1: The smell of grilled bratwurst and cheap beer should have felt like home. Instead, it felt like a…

CH2 – After My Car Accident, My Husband Chose Fine Dining With His Female Friend—Police Made Him Regret It…

Part 1: The smell of rain on hot asphalt has always made me uneasy. There’s something metallic about it—like ozone…

End of content

No more pages to load