Part 1

The October wind cut through my apple-print cardigan like it wanted to make a point.

That cardigan had been a hit with my fourth-graders, but standing on the porch of the house I’d lived in for thirty-two years, it didn’t feel charming anymore.

I gripped my house key—a useless piece of metal now—and looked at my brother. Wesley stood just inside the doorway, smiling the way car salesmen smile when they’re about to close a deal.

“Dad left everything to me, Ramona,” he said, his tone smooth as glass. “You’ve got twenty-four hours to get your things out.”

Behind him, our sister Judith was pulling books off the shelves—my books, the first editions Dad and I had spent summers hunting for at yard sales. She was dropping them into garbage bags like junk mail.

“Wesley, this is insane,” I said, voice shaking. Mrs. Patterson from next door was on her porch pretending to water flowers that had been dead since September. “I live here. I’ve been taking care of Dad for five years.”

“And now Dad’s gone.” Wesley adjusted his expensive watch—the one he made sure everyone knew cost more than my annual salary. “He finally saw sense before he died. Realized you were just a leech, living off his pension while the rest of us made something of ourselves.”

Across the street, Mr. Yamamoto was checking his mailbox for the third time, pretending not to listen. The Henderson kids had stopped their bikes halfway down the block. The whole neighborhood was watching me get evicted from my own home.

“Where am I supposed to go?” The question came out small, a child’s voice escaping a grown woman’s throat. I felt eight years old again, begging Wesley to let me into the treehouse he’d built a “no girls allowed” sign for.

“That’s not my problem.” Wesley turned to Judith. “How much longer?”

Judith appeared with another garbage bag bulging with my winter clothes. She didn’t meet my eyes. “Your immediate necessities,” she said softly. “Clothes, toiletries, your teaching supplies. Wesley says we’ll send the rest later.”

“Judith, please,” I said. “You know this isn’t right. You heard Dad make me promise never to leave him alone.”

She turned away, guilt flickering across her face. “Wesley has the will, Ramona. It’s legal. Dad signed it.”

“Two months ago?” I shouted. “When he couldn’t even remember what day it was? When he called me Mom because of all the morphine?”

Wesley stepped forward until I had to back up onto the porch I’d helped Dad paint last spring. “Careful, Ramona. Slander’s a serious accusation. I have witnesses who’ll say Dad was perfectly lucid when he signed. And I already called the police to let them know what’s going on, so don’t make a scene.”

Right then a patrol car rolled past, slowed, the officer giving Wesley a little nod before continuing down the street. Wesley smiled—that same cruel smile from when he used to tickle me until I cried and then tell Mom I was being dramatic.

“Twenty-four hours,” he said. “After that, anything left becomes property of the estate. Meaning mine. Oh, and don’t try the basement or back doors. We’ve changed all the locks.”

The door shut with a click that sounded like the end of my life.

I stood there on the porch with two garbage bags and a key that fit nowhere. Behind the curtains, shadows moved through the house where I’d grown up—the kitchen where Mom taught me to make soup, the hallway where Dad and I hung our framed puzzles, the window where he used to wave each morning when I left for school.

I walked to my fifteen-year-old Honda, tossed the bags in the back, and sat staring at the steering wheel until my hands stopped shaking enough to turn the key. Through the dining-room window I could see Wesley and Judith moving around, probably deciding which of Dad’s things to sell first.

That window used to be where Dad waited for me after work, waving like I was still his little girl coming home from school.

I didn’t know then what I know now.

I didn’t know Dad had been three steps ahead of Wesley.

I didn’t know about the hidden safe, the real will, or the camera that had captured everything.

I didn’t know that in forty-eight hours Wesley’s smile would vanish forever, when Dad’s estate lawyer would walk into his gleaming house and say five words that would change everything.

Right then, sitting in my car with my whole life in two garbage bags, I only knew one thing:

Dad called me his sunshine.

And sunshine always finds a way through the clouds.

Wesley thought he’d locked me out.

But he’d forgotten Dad taught me to keep spare keys in unexpected places.

The question was whether I could find them in time.

Three Weeks Earlier

It was a Tuesday, 3:47 p.m., when the call came. I remember because I’d just written Excellent! on Timmy Morrison’s spelling test—the first time he’d ever gotten necessary right.

“Is this Ramona Thorne?” The voice was professional, gentle. “This is Mercy General Hospital. Your father, Theodore Thorne, was brought in about an hour ago. He suffered a massive heart attack. You should come right away.”

The red pen rolled across the paper, leaving a long crimson streak like a wound.

I don’t remember the drive, just the antiseptic smell of the hospital corridor and the too-bright waiting-room lights. Wesley arrived in his BMW still in golf clothes, irritated at being pulled away from the country club.

Dad was gone before sunset.

Mrs. Patterson had found him in the garden, collapsed beside his tomato plants. The nurses said he’d still been clutching three perfect red ones when the paramedics arrived—as if he’d been choosing the best for dinner.

I’d been living with Dad for five years, ever since my divorce from Robert. What started as “a few weeks until I get back on my feet” became permanent when I realized Dad needed help.

It began with little things: forgetting to eat lunch, leaving the stove on, missing his medication.

The man who’d carried mail through thirty years of New England winters was fading like an old photograph.

Wesley called it freeloading.

“You’re thirty-eight, Ramona,” he’d sneered. “Living in your childhood bedroom like a failure.”

He lived fifteen minutes away in a six-bedroom house but could spare only one Sunday a month for Dad.

Judith was better, though not by much—weekly visits with store-bought cookies passed off as homemade, her realtor blazer still crisp, her eyes always on her phone.

“Not too much for you, right?” she’d ask at the door, already halfway back to her SUV.

They saw duty as charity. I saw it as love.

Those five years were the best and hardest of my life.

Mornings started with Dad trying to make coffee, his hands trembling until I took over—two sugars, splash of milk, stirred counter-clockwise the way Mom used to. We’d sit together while I prepped lesson plans and he told the same stories from his postal route.

Evenings were Jeopardy! and tea, Dad shouting the wrong answers with absolute confidence.

He’d help brainstorm class activities. “Make them fall in love with reading, Mona,” he’d say. “A child who reads becomes an adult who thinks.”

But the last year… the confusion deepened, his hands grew unsteady, the man who’d memorized every address on his route began getting lost walking to the corner store.

There were still perfect moments, though—like the night before he died, when the morphine haze lifted for an hour. He squeezed my hand and whispered, “You’ve been my sunshine. Don’t let anyone tell you different. You came back when I needed you most. That’s not failure, baby girl. That’s love.”

I’d kissed his forehead and promised I’d see him in the morning.

I didn’t know that less than twenty-four hours later he’d be gone—and three weeks later, my brother would change the locks on the only real home I had left.

The funeral was small. Dad wouldn’t have wanted a spectacle.

His postal-service friends lined the aisle, silver-haired men with shaky salutes and stories about “Steady Teddy Thorne, the man who never missed a shift.”

Each one clasped my hand and said the same thing: Your father was the best man I ever knew.

Wesley’s eulogy sounded like a quarterly earnings report. He spoke about “responsibility” four times and “love” not once.

Judith wept beautifully into a lace handkerchief that matched her designer dress, crying just enough to look cinematic.

When it was my turn, I read Mom’s old poem—the one she’d written for Dad’s birthday before she passed. My voice broke only on the line about coming home.

Afterward, while mourners ate ham sandwiches in the church basement, Wesley cornered me by the coffee urn.

“We need to discuss the estate,” he said. “The house, Dad’s savings, pension benefits.”

“Wesley, we buried him an hour ago.”

“Someone has to be practical.” He already had his phone out, showing me a real-estate app. “The house is worth at least three-hundred thousand, split three ways. I had an appraisal done months ago.”

“You had it appraised while he was dying?”

“That’s called planning, Ramona. Something you might understand if you’d ever owned property instead of living off others.”

I wanted to throw the coffee at him, but Mrs. Patterson was watching—and Dad would have hated a scene.

So I walked away, leaving him alone with his spreadsheets and his soulless ambition.

For the next few days I tried to return to normal. My principal, Mr. Goldman, told me to take time off, but I needed my students. Their sticky hands and lopsided drawings kept me tethered.

Susie Chen gave me a stuffed bear. “Bears give the best hugs when you’re sad,” she said.

Wesley’s campaign began immediately.

The morning after the funeral he arrived with a locksmith. I was sitting in Dad’s chair, wearing his old cardigan.

“What are you doing?” I demanded.

“Changing the locks. We can’t have random people accessing estate assets.”

“I’m not random people. I live here.”

“For now,” he said. “But that’s going to change. Dad saw his lawyer recently about some updates.”

“What kind of updates?”

“You’ll find out soon enough.”

Judith came two days later with a measuring tape and camera, talking about “staging” and “curb appeal.”

“We could list by Christmas,” she said.

“I live here,” I repeated.

“Wesley says Dad felt you’d taken advantage long enough,” she murmured.

Taken advantage. The words burned. I’d wiped Dad’s face when he couldn’t hold a spoon. I’d cleaned him when he was too weak to stand.

But to them, I was a freeloader.

Thursday morning, I left for school as usual. When I returned that evening, my key no longer fit. Wesley met me at the door with his ultimatum, a police warning, and that satisfied grin that made me want to scream.

That night I slept in my car in the elementary-school parking lot, wrapped in three sweaters Judith had packed, wondering if she’d known I’d need them all.

Every time I drifted off, I woke hearing Dad’s voice asking for his medication.

By dawn my phone battery was dead, which was a mercy—it stopped me from calling Wesley to beg.

At five a.m. I went inside the school with my teacher’s key, washed my face in the staff bathroom, and changed into the spare dress I kept in my closet.

By the time Mr. Goldman arrived, I was at my desk pretending everything was normal.

During lunch, I called three lawyers. Two refused to meet without a thousand-dollar retainer. The third, a weary man named Peterson, listened five minutes before sighing.

“Challenging a will can take years and cost tens of thousands,” he said. “If your brother has a signed document and you can’t prove coercion, it’s an uphill battle. I’m sorry.”

During recess I stood watching kids play hopscotch on squares I’d painted last spring and heard Dad’s voice again: I’m not a rich man, Mona, but I’m a prepared man.

Prepared. That was Dad’s word for everything.

Batteries labeled, emergency cash hidden, documents in the basement safe.

The safe.

My pulse quickened. Wesley had changed the main locks, but had he remembered the old basement door behind the overgrown forsythia bush? The one only Dad and I used when we needed the lawnmower?

That evening, I waited until seven o’clock, when Wesley would be at his country-club dinner and Judith at an open house. I parked two blocks away and cut through the Hendersons’ yard, whispering apologies to their yapping terrier.

The forsythia scratched my arms as I pushed through to the basement door. My key slid in easily—the lock was older than I was. Wesley had forgotten it existed.

The basement smelled of dust, old paint, and Dad’s cologne. I used my phone flashlight to find the safe behind the water heater.

“Just in case, Sunshine,” Dad had said last year, making me repeat the combination three times. “Your birthday, your mother’s birthday, and the year we bought this house.”

It opened on the first try.

Inside were insurance papers, Mom’s wedding ring, and a manila envelope labeled For Ramona — Open Only If Needed.

My hands trembled as I opened it.

First was a business card: Foxworth & Associates — Estate Law.

On the back, in Dad’s shaky writing: He knows everything. Trust him. — Dad.

Then came a second will, dated one week before the version Wesley had shown me—properly notarized and witnessed by Mrs. Patterson and Mr. Yamamoto.

This one left the house to me, with $50 000 each to Wesley and Judith.

But the third item made my knees give out.

A USB drive.

A yellow sticky note in Dad’s handwriting: Mona, if you’re reading this, Wesley has shown his true colors. I installed a camera in my bedroom when I started getting confused. I needed to know what happened during my bad spells. I’m sorry you have to see this. Be strong, Sunshine. P.S. Foxworth has copies.

For the first time since the funeral, I smiled through tears.

Dad had been prepared, just like he promised.

Part 2

By the time I reached the school parking lot the next morning, the USB drive felt heavier than gold in my pocket.

The sun was just climbing over the rooftops, pale and cold, the kind of morning light that makes everything look sharper, more honest.

Dad always said the truth loved daylight.

I sat in my car for a few minutes, gripping the steering wheel, trying to decide if I was crazy for what I was about to do. Then I dialed the number on the card.

A pleasant voice answered. “Foxworth and Associates.”

“My name is Ramona Thorne,” I said, my voice cracking halfway through. “My father was Theodore Thorne. He told me to call you if … if something went wrong.”

There was a pause, then, “One moment, Ms. Thorne.”

Thirty seconds later a calm, older man came on the line. “Ramona, this is Gerald Foxworth. Your father said you might call. Can you come to my office in an hour?”

Foxworth’s office looked exactly like somewhere Dad would have trusted: small, tidy, lined with books and photographs of grandchildren instead of diplomas. The man himself was silver-haired, wearing a cardigan instead of a suit jacket.

He stood as I walked in. “Your father was one of the finest men I ever met,” he said, shaking my hand with both of his. “I’m very sorry for your loss.”

I didn’t waste time. I spread everything on his desk: the fraudulent will Wesley had used, the second one from the safe, and the USB drive with Dad’s note.

Foxworth read both wills carefully, humming softly under his breath. Then he plugged in the drive.

The video flickered to life—grainy, but clear enough.

There was Wesley, standing over Dad’s bed, holding a clipboard. Dad looked so frail, propped up on pillows, his eyes glazed from medication.

“Just sign here, Dad,” Wesley said, voice calm but hard. “It’s for your medical power of attorney.”

“Where’s Mona?” Dad slurred. “I want Mona.”

“She’s at work. This is just paperwork. Sign it, okay?”

“Doesn’t look right,” Dad murmured. “What am I signing?”

“Dad, just sign.”

The camera caught everything: Wesley guiding Dad’s hand across the line, forcing the pen between his trembling fingers. Then Wesley folded the papers neatly, tucked them into his briefcase, and walked out without a glance back.

My stomach turned.

Foxworth paused the video and took off his glasses, wiping them slowly. “Your father came to see me a week after this,” he said quietly. “He told me he’d signed something he didn’t understand. He was terrified your brother had tricked him. That’s when we drafted the real will—the one you found—with witnesses he trusted.”

“So the will Wesley filed is …”

“Fraudulent. And given your father’s medical records, this is elder abuse and forgery.”

I covered my mouth. “Dad knew.”

Foxworth nodded. “He was angry—but more than that, he was sad. He said, ‘My son measures love in dollars, but Ramona measures it in moments.’”

The words broke me.

He gave me a tissue and let me cry. Then he leaned forward, voice steady again. “We’re going to make this right. But first, I need both your siblings in the same room. Today.”

Wesley’s house looked like something from a luxury-home magazine—glass walls, imported stone, and not a single photo that wasn’t staged.

When he opened the door and saw Foxworth beside me, his salesman smile faltered.

“Ramona. Mr. Foxworth. What’s this about?”

Foxworth extended a hand. “Gerald Foxworth, representing your father’s estate.”

Wesley didn’t take it. “My father’s estate is already settled.”

“Then you won’t mind if we review a few details,” Foxworth said pleasantly.

Wesley hesitated but stepped aside. Inside, everything gleamed—white marble floors, chrome fixtures, a giant framed photo of him shaking hands with a celebrity athlete he’d sold a car to.

Nora, his wife, appeared in the doorway, perfectly made-up even on a Saturday morning. “What’s going on?”

“Nothing, honey,” Wesley said. “Just a misunderstanding about Dad’s will.”

Judith arrived fifteen minutes later, breathless and nervous. “Wesley texted—said it was urgent.”

We all sat in the living room that looked more like a showroom than a home. I could smell the faint citrus cleaner and money.

“This is harassment,” Wesley began, confidence returning. “Dad’s will was filed with the court. Everything’s legal. Ramona’s having trouble accepting reality.”

Foxworth smiled mildly. “Which will are you referring to? The one you had him sign while he was on morphine, or the valid one drafted with witnesses a week later?”

Wesley blinked. “What are you talking about?”

I took out my phone, pulled up the video, and hit play.

Dad’s confused voice filled the immaculate room: ‘Where’s Mona? This doesn’t look right.’

The sound of Wesley’s voice ordering him to sign echoed off the marble.

Nora gasped, hand flying to her mouth. Judith’s face went white.

When the screen went dark, Foxworth’s calm voice cut through the silence.

“That’s elder abuse and fraud.”

Wesley shot to his feet. “You’re taking that out of context! Dad wanted to make changes. He said Ramona was bleeding him dry!”

“Your father was on sixty milligrams of morphine,” Foxworth said evenly. “He was barely conscious. Meanwhile, I have a video of him in my office a week later—completely lucid—certified by his doctor as competent, explicitly stating his wishes.”

Judith finally spoke, voice trembling. “Wesley… you said Dad wanted this. That he thought Ramona was manipulating him.”

“I was protecting our interests!” Wesley snapped.

“By forging his signature?” I said.

He turned on me. “You lived there rent-free for five years!”

“While being paid a caregiver’s wage out of his savings,” Foxworth interrupted, opening a folder. “All documented. All taxed. She wasn’t living free—she was working.”

Nora stood abruptly, eyes blazing. “Wesley… is this true?”

He reached toward her. “Honey, listen—this was about protecting what we’ve built—our lifestyle—”

“Our lifestyle?” she repeated, voice shaking. “You mean the one built on stealing from your dying father?”

She turned to me. “Ramona, I’m so sorry. I had no idea.”

Foxworth took out his phone. “Mr. Thorne, we have two choices. I can call the district attorney right now and let you explain this video to them—or we can resolve it quietly. Your sister gets the house as your father intended. You return what you’ve taken. You walk away. You have sixty seconds.”

Wesley’s confidence collapsed. He looked from me to Nora to Judith, calculating, sweating.

“This is blackmail,” he muttered.

“No,” Foxworth said. “Blackmail is threatening to expose something in exchange for gain. This is consequence.”

Judith’s voice broke. “Just sign, Wesley. Please. Haven’t we done enough?”

He looked around the pristine room—at the wife already stepping back from him, the sister glaring, the other sister silent and steady. Then he slumped.

“Fine,” he whispered. “I’ll sign.”

It took three hours to sort everything. Foxworth produced paperwork like a magician pulling scarves from a hat.

Wesley signed over the deed, returned seventeen thousand he’d already withdrawn from Dad’s accounts, and signed a statement waiving any future contest to the real will.

By the end, his hands were shaking. Nora stood in the corner on the phone—calling her lawyer, no doubt.

When we left, Wesley didn’t follow us out. His perfect house had never felt so hollow.

That afternoon, I stood in Dad’s kitchen again. My kitchen.

The air smelled like home—coffee, lemon cleaner, the faint ghost of tomato plants through the open window.

Mrs. Patterson and Mr. Yamamoto were waiting at the table, smiling.

“You knew,” I said softly.

Mrs. Patterson nodded. “Your father made us promise. He said if Wesley tried anything, we were to wait for you to find the safe.”

Mr. Yamamoto smiled faintly. “Your father said, ‘Wesley smart with money. Ramona smart with heart. Heart more important.’”

I laughed through tears. “He really said that?”

“He did,” Mrs. Patterson said. “And he was right.”

Three months later, the house was mine again—not as property, but as home.

I repainted Dad’s chair rail, replanted his tomato garden using the last seeds he’d saved, and turned the dining room into a tutoring space for my students. The laughter of children drifted through rooms that had once echoed with grief.

Every Sunday Judith came for dinner. We were careful at first, circling each other like strangers, but the walls slowly fell.

“I was weak,” she admitted one night, stirring her coffee. “Wesley always made me feel small. I thought siding with him made me strong.”

“Dad loved us all,” I said. “He just knew I needed him—and he needed me.”

She nodded, eyes bright with tears. “You were his sunshine.”

Outside, the tomato vines rustled in the breeze, heavy with fruit.

Wesley’s fall was quick. Word spread through the country club and the dealership. Customers didn’t want to buy from “the guy who defrauded his dying father.” Nora filed for divorce within the year, taking half of what remained.

I didn’t gloat. I just kept living.

And one rainy December afternoon, while cleaning Dad’s old mail-carrier lunchbox, I found one last envelope: Open on a bad day.

Inside, in his shaky handwriting:

My Sunshine Girl,

If you’re reading this on a bad day, remember storms pass, but love remains.

Wesley’s anger comes from fear—fear that love can’t be bought.

Judith follows strength; show her yours, and she’ll find hers.

The house is yours because you made it a home.I’m proud of Wesley’s success and Judith’s ambition, but I’m in awe of your kindness.

Don’t ever feel small for choosing love over money.Your devoted father,

Theodore ThorneP.S. The tomatoes will grow better if you sing to them. Your mother always did.

I sat there for a long time, reading it over and over, until the paper blurred.

Now, every morning, I drink coffee in Dad’s chair, stirring it counter-clockwise the way he liked. The garden outside glows red with tomatoes, and sometimes I swear I can smell his aftershave in the breeze.

The locks Wesley changed are gone, replaced with new ones. I keep spare keys with Mrs. Patterson and Mr. Yamamoto—neighbors who proved that witness is another word for love.

Sometimes, when my students run through the yard after tutoring, laughing and spilling their backpacks on the porch, I look at the house and feel Dad there—in every nail, every board, every bit of sunlight.

He wasn’t a rich man, but he was a prepared one.

And because of that, love won over greed. Truth over lies.

And I got to keep not just the house, but the proof that goodness can still win if someone, somewhere, keeps the real keys hidden safe.

Part 3

The next spring arrived slow and golden.

The kind of New England spring where the air still carries the edge of winter, but you can smell life returning in the thawing earth.

For the first time in years, I wasn’t rushing anywhere. No lawyers. No tears. No shouting matches with my brother through a locked door. Just mornings with coffee and sunlight slanting across the table Dad built.

The house had changed since the day Wesley threw me out.

It felt lighter now—like grief had been scrubbed from the corners.

There were flowers in Mom’s old vases again, laughter from my tutoring kids echoing down the hall.

But every day, in some quiet way, I still talked to Dad.

When I watered his tomatoes, I told him about my students.

When I fixed a leaky faucet, I told him I finally learned to use the wrench properly.

And when I sat on the porch at dusk, I told him about Wesley and Judith.

Because even though justice had been served, the story wasn’t finished. Not really.

It took only a few months for Wesley’s empire to start crumbling.

The dealership he’d been so proud of lost its biggest accounts once word spread about what he’d done. His country-club friends—those men who used to slap him on the back and call him “Top Closer”—stopped returning his calls.

Nora left quietly, but thoroughly, taking half of everything, including the lake house he’d bragged about for years.

Judith told me later that Wesley moved into a rented condo on the other side of the state, somewhere anonymous.

He’d sold the BMW for something cheaper, smaller.

He wasn’t on social media anymore. No more perfect family pictures. No more smiling at ribbon cuttings.

I didn’t feel joy in his fall.

I felt… relief.

Because maybe, finally, he’d have to sit still long enough to look at the pieces of himself he’d been running from since Mom died.

Dad used to say Wesley wasn’t born cruel, just afraid of being ordinary.

And fear, Dad always warned, makes people do desperate things.

Judith came by every Sunday now.

At first she brought takeout to make up for the years she hadn’t cooked, but eventually, she started cooking again—Dad’s recipes, Mom’s soups. The kitchen smelled like family again.

We didn’t talk much about the day at Wesley’s house, not at first.

But one evening, as rain tapped softly against the windows, she finally said, “You know what I keep remembering? That day at the funeral. I cried so hard, and everyone thought it was grief. But I was crying because I was terrified. I didn’t know how to live without someone telling me what to do.”

She stared into her coffee. “Wesley told me if we didn’t sell the house, we’d lose everything. I believed him. I always believed him.”

“Because you wanted to,” I said gently. “He made it easy. He made decisions so you didn’t have to.”

She nodded. “I was jealous, too. Of you. Dad called you sunshine. He called me his ‘little storm.’ I used to think that meant I ruined things.”

I reached across the table, took her hand. “He called you that because you brought energy into every room. He just wished you’d learn to stop blowing yourself over.”

She laughed through her tears. “You sound just like him.”

Maybe that was the greatest compliment anyone could ever give me.

It was early summer when Mr. Foxworth came by with paperwork—final confirmation that the fraudulent will had been voided and the property fully restored in my name.

He looked older than I remembered, but still carried that quiet steadiness I’d come to associate with truth.

He set his briefcase down on the kitchen counter. “Your father would’ve been proud, Ramona. You handled all this with grace.”

“I had help,” I said.

He smiled. “You had courage. That’s rarer.”

We drank coffee and talked about Dad. About how he’d spent his last years planning for everything he could.

“Your father came to me months before his health declined,” Foxworth said. “He said, ‘I can’t stop my memory from fading, but I can leave my conscience clear.’ He didn’t just plan his estate. He planned your protection.”

Hearing that made my chest ache in a good way.

Dad had always been steady, like gravity itself. Even gone, he was still holding me up.

When Foxworth left, he shook my hand and said, “You know, every family has a story about greed. Few have one that ends with grace.”

That night, I wrote his words on a sticky note and put it on the fridge. Grace over greed. It felt like a family motto.

By July, the tomato plants were enormous—lush, green, heavy with fruit.

Dad’s variety, Crimson Heritage, had always been the envy of the neighborhood. He used to sing to them while watering, a ridiculous made-up song that rhymed “photosynthesis” with “delicious.”

I started singing it, too. At first it felt silly, but then it didn’t.

The plants thrived. The neighbors teased me kindly about having my father’s green thumb.

Every Saturday, I took baskets of tomatoes to the school food drive. My students would wave from their parents’ cars, yelling, “Miss Thorne, are those Grandpa Ted’s tomatoes?”

I’d smile and say, “They sure are.”

In a way, Dad was still feeding people.

Still giving.

Still growing.

In December, a Christmas card arrived in the mail with no return address.

Inside was a photo of Nora standing by a small bookstore somewhere coastal, a “For Lease” sign flipped to “Open.”

On the back, in neat handwriting:

Ramona —

I’m sorry for my part in everything. I told myself it wasn’t my business, but silence is its own kind of guilt. I left Wesley, started over, and I’m happier than I’ve ever been. Your father would be proud of you. He taught us both that decency is its own inheritance.

— Nora

I stood in the kitchen, reading it twice, then tucked it inside Dad’s old recipe book between Meatloaf (extra ketchup) and Mom’s cinnamon rolls.

People can change, I thought. Even the ones who watched from the sidelines.

The following spring, Sherwood Elementary invited me to speak at the fifth-grade graduation.

It had been a long time since anyone asked me to speak in front of a crowd. I was nervous, but when Principal Goldman introduced me as “the heart of this community,” the words warmed me all the way through.

I told the kids a story—not about greed or betrayal, but about planting.

“Sometimes,” I said, “you plant something and it doesn’t bloom right away. Sometimes it takes patience. Sometimes it even looks dead. But if you keep watering, keep believing, one day you’ll wake up and see green shoots pushing through the dirt. That’s what love is. That’s what kindness does.”

The parents applauded. Some of the teachers cried.

Afterward, a boy handed me a paper drawing of a tomato plant with a gold sun in the corner. On the stem, in crooked letters, he’d written:

‘Be sunshine.’

I framed it that night and hung it above the kitchen table.

Two years passed.

Then, one late August afternoon, there was a knock on my door.

I opened it and froze.

Wesley stood on the porch.

He looked nothing like the brother I remembered.

The polished arrogance was gone. His suit was wrinkled, his eyes tired. He was thinner, older.

“Can I come in?” he asked.

I hesitated but stepped aside.

He looked around the house—the same house he’d thrown me out of—and his face crumpled. “You fixed the place up,” he said softly.

“I made it home again.”

He nodded. “You did.” He rubbed a hand over his jaw. “I owe you an apology.”

I waited.

He took a breath. “I lost everything. The business, the house, Nora. But the worst part wasn’t that. The worst part was realizing how much of Dad I never understood. He worked his whole life for us, and I treated him like an obstacle.”

There was pain in his voice, real and raw.

“I can’t undo what I did,” he said. “But I want you to know—I see it now. All of it. The nights you spent with him, the way you kept him comfortable. He talked about you all the time, didn’t he?”

I nodded. “He did.”

Wesley looked down. “He was right to leave you the house.”

We stood there in silence, the air thick with all the years between us.

Finally, I said, “Would you like some coffee?”

His eyes widened. “You’d still—after everything—?”

“Dad taught me to offer coffee before judgment,” I said. “Besides, it’s cold out.”

He smiled weakly. “Two sugars, splash of milk?”

I froze. “How did you—?”

He shrugged. “Old habits die hard.”

That was the first small step. Not forgiveness exactly—more like the beginning of one.

Full Circle

Over the next few years, life found its rhythm.

Judith remarried—a kind man who made her laugh. Wesley started working at a nonprofit that trained young people in automotive trades. He sent updates sometimes—pictures of kids smiling beside rebuilt engines, hands greasy, eyes proud.

I sent him tomatoes every summer.

“Still singing to them?” he’d text.

“Every day,” I’d reply.

He’d send back a sun emoji.

When I turned fifty, the whole neighborhood threw a party in my yard. My students—some now grown with kids of their own—came by with flowers and stories. Judith brought a giant sheet cake.

And in the middle of it all, Mr. Foxworth appeared, older now but still spry.

“I’ve been holding something for you,” he said, pulling out a small envelope. “Your father left instructions to deliver this on your fiftieth birthday.”

My hands shook as I opened it.

Inside was a single photo—Dad standing in the garden, dirt on his hands, sunlight behind him like a halo.

On the back, in his handwriting:

If you’re reading this, you’ve made it, Sunshine. Keep the door open for others. Love is the only thing that multiplies when divided.

I looked up and saw Wesley and Judith laughing near the grill, the neighbors dancing, kids running through the grass.

I realized the house was full again—of noise, of life, of the kind of joy that doesn’t ask permission.

Dad had been right all along: preparation wasn’t just about plans. It was about people. It was about leaving behind a map of love for those who might get lost.

That night, after everyone left, I sat on the porch as the sun dipped behind the trees, painting everything gold.

I thought about the chain of events—how one forged signature tried to erase a lifetime of love, and how truth, in the end, outlasted everything.

The tomatoes rustled in the breeze, ripe and ready for harvest. I whispered to them softly, the same silly tune Dad used to sing.

“Grow strong, little ones. The world still needs sweetness.”

For a long while I just sat there, watching the light fade, feeling the air grow cool against my skin.

And in that quiet, I could almost hear him—Dad’s voice, steady and proud:

“Told you, Sunshine. Always keep a spare key.”

THE END

News

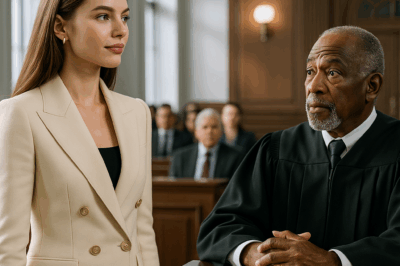

Judge Caprio Left SPEECHLESS When Billionaire’s Daughter Said “I Own You”

Part 1: Imagine walking into a courthouse like you own it—not metaphorically, but actually believing your father’s billions have purchased…

My Wife & Chef Poisoned An Inspector To Frame Me. Then A Lawyer Revealed Mom’s $83M Secret

Part 1: I used to think rain was cleansing. Now it just felt like penance. It had been coming down…

At Her Graduation, My Daughter Thanked Only Her Father and Ignored Me, But She Didn’t Expect My Reaction

Part 1 The words hit like a gut punch I’d been bracing for all morning, but still couldn’t absorb. “Dad,…

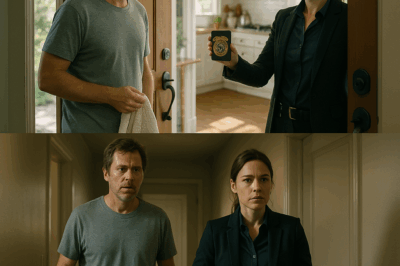

I WAS COOKING BREAKFAST WHEN A DETECTIVE KNOCKED ON MY DOOR

Part 1: The smell of burnt toast was the first wrong note in an otherwise ordinary morning. The kind of…

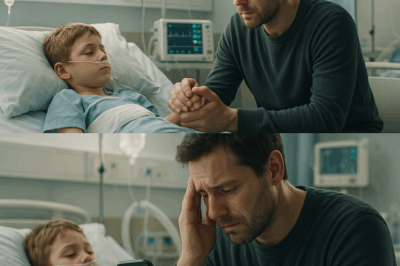

MY 9-YEAR-OLD SON WAS IN THE ICU WHEN MY WIFE CALLED: “TOMORROW’S MY MOTHER’S BIRTHDAY—COME…”

Part 1 The machines hummed like ghosts, whispering secrets I didn’t want to hear. ICU lights don’t flicker—they stab. Every…

HOA Karen Kept Stealing My Mail—So I Hid a Mouse Trap in My Mailbox She Triggered It

Part 1 At precisely 10:02 a.m., the suburbs exploded. A shriek pierced the quiet cul-de-sac of Juniper Quay, echoing off…

End of content

No more pages to load