Part One:

Love doesn’t survive splinters. It can live with dents and scratches and a cracked tile or two, but once you get splinters in the grain, every touch reminds you where it broke. Three days ago I thought I was building the kind of life you see on bank brochures: two-story farmhouse with good bones, wraparound porch half done because I kept choosing paying customers over our railings, a construction business that finally paid bills on time, and a wife who looked like she’d been poured into every room by an interior designer. Melanie had that sharp-edged beauty executives pay retainers to be near. When she smiled, men straightened, servers hurried, doors opened.

Now when I picture her smile, I hear breaking glass.

It started at her company’s spring party—one of those rooftop things at a hotel that serves tiny plates with names longer than the food itself. I wore my one good shirt. I held a beer the way you hold a business card you’re afraid to bend. Melanie worked the terrace like she owned the view. She wore a cream dress with clean lines and a belt no one else could see yet: twelve weeks and counting. Only in hindsight did that second detail sharpen.

Cal Dunston showed late, like a man auditioning for the role of Important. Silver hair that probably had its own stylist. Suit that could pay for a kayak. He kissed both of Melanie’s cheeks. She laughed that new laugh she’d been practicing, the one with no air in it. Then—because a person like Cal doesn’t just greet, he claims—he slid his hand onto the small of her back and steered her toward the glass.

Jenny Morrison, our neighbor and amateur town crier, had scored an invite on the flimsy pretext that she’d once done PR for a car dealership. She materialized at my elbow with a flute of champagne and a hungry look.

“You seeing this?” she whispered.

“I’m seeing my wife network,” I said.

Melanie leaned toward Cal. The room’s sound thinned.

“He’s my work husband,” she purred, loud enough for the circle to catch it, soft enough that if you got mad she could call you paranoid.

People laughed. Cal flashed the smile that makes interns choose the wrong future. Melanie’s hand—my wife’s hand—rested on his sleeve like she was claiming a tax deduction.

That sentence—work husband—landed inside me like a nail with no head, the kind you only feel when it snags skin. I swallowed a mouthful of beer that tasted like a dare. When she finally let me catch her eye, all I saw was calculation. She winked. It wasn’t for me.

I didn’t make a scene. I didn’t throw anything. I did what men in small towns do when the horizon between pride and humiliation starts to buckle: I drove home slow with the windows down and let the road think for me.

Two nights later, Jenny hosted one of her legendary backyard barbecues—burgers, gossip, and the sense she was secretly filming a pilot called Neighbors Behaving Badly. I was by the fence nursing a beer when Sasha—Mel’s best friend and accessory—leaned in close to Melanie and asked, loud in the way people get when they think a party’s noise is cover, “So when are you telling Tom about the little surprise?”

Melanie laughed. You know the sound a glass ornament makes when it slips and you know it’s going to break and you can’t catch it? That.

“Why ruin a good thing? Cal says we wait until after his promotion goes through.”

Cal. Like three letters could be a future. Like a man’s first name could be a verb.

“Tom’s so buried in his little projects,” Melanie went on, “he barely notices I exist. This baby deserves better than sawdust and broken dreams.”

The bottle slid out of my hand and shattered on Jenny’s concrete. Heads swiveled. Melanie didn’t flinch. I left before anyone could decide what to do with the facts.

At home I did what hurt people do when truth finally stops whispering and starts yelling: I went through our shared calendar. Tuesday: Dr. Sarah Williams, 10:15 a.m. OB-GYN written like a joke turned appointment. It had been labeled “routine checkup.” Nothing about Melanie had been routine for months: the expensive jewelry that appeared like a sponsor’s gift, the late nights that smelled like other people’s cologne, the new habit of looking at me like I was drywall she hadn’t ordered.

Tuesday came like a truck you can’t sidestep. I followed her silver BMW from our place on Griggs Mill Road to the medical complex downtown and parked far enough away that my shame could pretend it had choices. I watched her go in with that walk she wears when she’s sure of the room. An hour later she came out smiling into her phone, the kind of smile that used to make me feel tall.

“Cal, it’s confirmed. Twelve weeks. I know. I know. Tom doesn’t suspect a thing.”

Her voice carried across the lot and stacked itself on top of every plank in me that had ever been proud. I sat there hearing the math: Valentine’s Day, when I was in Portland finishing a commercial renovation. She’d had the flu. Lies always have symptoms.

I drove home and parked in front of the porch I’d been promising to finish for two years. The lumber leaned like good intentions. The house looked tired, like it had finally decided to stop pretending it could be beautiful through willpower alone.

I decided to confront her. That was my first mistake. No, my first mistake was marrying the idea of her. The confrontation was just the invoice.

She came in around six with expensive Thai in a white bag and that after-work glow executives rub on like lotion. I stood between her and the kitchen.

“We need to talk,” I said.

She set the bag down, face sliding from everyday to frost. “About what?”

“About Cal,” I said, “and the baby you’re carrying that isn’t mine.”

Silence expanded until the refrigerator hum sounded like a siren. Then Melanie smiled, not warmth, but edges.

“Took you long enough,” she said. “I was wondering when you’d grow a brain.”

“That’s it?” I asked. “That’s all?”

“What do you want?” She climbed three steps and held the bannister like a model in a home magazine. “An apology? ‘It didn’t mean anything’? It means everything. Cal can give me things you can’t.”

“We own this house outright,” I said. “My business—”

“Is small-time contractor work in a dying mill town,” she cut in. “Cal is offering vice president at the regional office. Real money. Real opportunities. And his baby.” Her hand inside the cream dress flattened on a stomach most people would still call flat. “A baby with a trust fund and private school tuition already set aside. Not bad for three months of work.”

I saw the girl I fell in love with for about half a second then watched her harden into the woman who believed the world was a catalog you bought out if you just learned the right names for things.

“Get out,” I said.

She blinked. “Excuse me?”

“Pack your things,” I said, “and get out of my house tonight.”

“Don’t be dramatic,” she said, the way you say “don’t be poor” when you’ve forgotten the word “kind.” “We can work this out. You keep the house. I keep the baby. Everyone wins.”

I carried her suitcases from the closet and threw them on the bed. I stood in the doorway while she folded her life into leather. She moved slow, like the clock owed her respect. I didn’t move. When she was done I took the suitcases down and pitched them onto the gravel. Blouses burst like doves. Lace flashed in the porch light.

“You’re making a mistake,” she said from the threshold.

“No,” I said, and closed the door on the person who had taught me that even love has safety codes.

Through the living room window I watched her gather her things with the dignity of a person whose currency is being watched. Jenny Morrison was in her yard pretending not to stare and recording every detail to run through the town at dawn. Good. Let it run. I opened a beer and sat on my half-finished porch and raised the bottle in a toast to the version of me who had ignored wind warnings in walls.

She drove off without a look back. I should’ve known it wouldn’t be that clean.

Around midnight, headlights dragged across my yard. Not Melanie’s BMW. A black Escalade. It idled like a threat. Three men got out, moving with the confidence of men who don’t do jail time because the story never sticks to them. The biggest was Grant Morrison—no relation to Jenny—Cal’s head of security. Six-four of muscle bought and paid for, with a shoulder bulge that said the expensive suit wasn’t the heaviest thing he was wearing.

I grabbed the bat I keep by the door. Habits are a kind of faith.

“Private property, gentlemen,” I said on the porch. “Time to leave.”

Grant smiled. His teeth were as white as lies. “Easy, contractor boy. Just a friendly chat.”

“Nothing friendly to chat about.”

“Boss says otherwise.” He nodded at the two younger men. “Says you’ve been harassing his girl. That’s not neighborly.”

“His girl was my wife six hours ago,” I said. “Funny thing about paperwork.”

“Here’s how this goes,” Grant said, stepping close enough that I could smell money and something under it. “You apologize to Mrs. Crane. You take her back nice and quiet. You pretend that baby’s yours.” He tilted his head. “Or we get creative about teaching manners.”

“Three against one?” I asked. “Doesn’t seem fair.”

Grant laughed, and the trees laughed with him. “Fair’s got nothing to do with this. This is about place. Yours is under my boss’s boot.”

I swung the bat. It cracked into Grant’s ribs with a sound I’ll think about when I’m old. He folded and for half a second I tasted the chance to win. Then a telescoping baton found my shoulder blade and the night went starry and small.

When light crawled back, I was in the trunk of a moving car. The air tasted like pennies. My wrists were zip-tied. Every pothole sent a small nuclear blast through my ribs. The trunk lid opened on pines. Grant’s face hovered above me like a bad moon.

“Rise and shine,” he said. “Time for your education.”

They hauled me out. The night had that October bite that makes you think about the quiet you’ve taken for granted. They’d left me in boxers and work boots. Humiliation is part of the lesson plan. Grant took out a hunting knife and drew a thin red line on my throat like a signature.

“You don’t touch what belongs to Cal,” he said. “You don’t threaten it. You don’t embarrass it.”

“She isn’t property,” I croaked through split lips.

“Everything’s property if you can afford it,” he said. He put the knife away and did something worse: nodded. The two others pinned my arms. Grant drew back his fist and for twenty minutes gave me a master class in damage without paperwork. They knew where bones break and when to stop. They knew how to paint with pain and keep the canvas alive. When they were satisfied, they dragged me to a tree and cinched the ties around the trunk until my hands went cold and dumb.

“Tell anyone and next time isn’t so friendly,” Grant said, and the way he said friendly made the word wish for another job. “Someone’ll find you. Or they won’t.”

They left. The sound of them walking away disappeared into the kind of dark that lets coyotes have opinions. I leaned my forehead against bark and made the mistake of thinking about everything at once. Then I stopped thinking. Thinking needs warmth. Anger makes heat.

I worked the ties against the bark until my wrists turned slick. I counted to a hundred twice, then I counted again, because counting is how you hold onto the part of you that speaks in sentences. A gray ribbon of dawn threaded through the trees around four. The zip ties surrendered with a soft snap, the way some victories do. I stood, swayed, staggered south because south felt like the word home. It took two hours to reach the old logging road. I must’ve looked like a cryptid. A Ford pickup stopped.

“Jesus, Tom,” said Pete Hoffman, retired cop, neighbor by miles not streets, a man who believes in minding his own business and the right time to contradict that belief. “What the hell?”

“Cal,” I said. “His boys.”

He eyed the damage. “Hospital.”

“No hospital,” I said. “No cops. Not yet.” That yet surprised me with its shape. “Somewhere safe.”

Pete weighs decisions like sacks of feed. He nodded. “My place.”

He cleaned the cuts with the kind of gentleness men can do when no one is grading them. He wrapped my ribs. He heated canned soup and didn’t make it taste like failure. When I could string words together, I told him the whole story. He listened like it was his job again.

“What’s your play?” he asked when I’d run out of details and excuses.

“I don’t know,” I said. It was the last time I would say that.

“You better figure it fast,” he said. “Men like Cal don’t issue warnings twice.”

That night on Pete’s lumpy couch, staring at a ceiling stained by years of wood smoke and weather, I felt my anger do what metal does when flame finds it: change states. I stopped shaking. The part of me that builds things—porches, stairs, walls that stand plumb in a world that lists—woke up.

Cal thought he’d taught me my place. He had. It wasn’t under his boot. It was where I could see the whole town at once.

Tomorrow, I would start measuring.

Part Two:

Pete’s cabin sits where the pines change their minds and let the sky through. The first morning I could stand up without seeing the floor tilt, I went outside and breathed cold air like it owed me. The porch steps creaked a complaint that sounded like my own ribs. Pete handed me coffee that tasted like someone boiled a shovel in it and said, “You going to be a nail or a hammer today?”

“Depends on the wood,” I said.

He grunted. That was his version of a benediction.

Healing turned into a schedule. Mornings, I walked the logging road until the bruises stopped arguing. Midday, I iced my shoulder and wrote lists. Evenings, I sat at Pete’s kitchen table and asked the two questions that build houses and bring down men: What’s load-bearing? Where’s the rot?

Pete had the kind of network small towns run on: a thin web of retired cops, mechanics, bartenders, linemen—the people whose names never make the programs but who spend their lives backstage. He called it “checking in on folks.” I called it a hand-cranked internet. He’d make a pot of coffee, dial a number, and let silence do the work while the other end filled it.

Within three days, we knew more about Cal than Cal’s own mirrors did. He wasn’t sloppy. You don’t get to be king of a county by using crayons on a ledger. But his edges were greasy. He parked shell companies in the back lots of respectable addresses. He “advised” three construction outfits that always snuck in on the second bid. He funded two council campaigns and one school board slate and made those men and women believe their votes were their ideas. He ran his empire like a church raffle—plenty of prizes, only certain tickets ever got drawn.

“What about the hands that do the grabbing?” I asked.

Pete stirred sugar into his tar like he was building concrete. “Grant runs point on fear. Couple younger bucks play wingman. Cal keeps his own hands clean.”

“Everybody’s got a Tuesday,” I said.

Pete raised an eyebrow. I told him about the way men like Grant treat routine like religion. Same gym. Same stool three nights a week. Same whiskey. Same alley.

“You’re not twenty,” Pete said.

“I don’t need to be,” I said. “I just need him to be drunk.”

I spent a week stacking strength and patience. Patience was harder. I wanted to run straight at the house that held all my broken outlines and set it on fire. Pete taught me what good cops know and good carpenters live by: anger makes shortcuts, shortcuts make collapses.

Tuesday came damp and mean. Mickey’s Bar throws neon like a lasso across the alley behind it. I waited where the lasso misses. Grant came out at midnight, laugh too big for a man walking alone. He cut across the wet pavement toward a black Mercedes that gleamed like it expected applause. His hand went to his shoulder the way a man finds his wallet in a crowded train. I stepped out.

“Evening,” I said.

He froze. Recognition moved across his face like cloud shadow. His hand kept going to the holster. I put the aluminum bat—a tidy, county-league thing from Pete’s garage—where it would do the most talking with the least paperwork. One sharp crack across the knuckles and the pistol clattered across the alley, slid into a grate, and disappeared like it had never been born.

“Easy,” I said, breath steady because that’s how you make decisions you won’t regret later. “We’re just going to have a conversation.”

“You’re dead,” he said through teeth he paid a lot for. “You don’t even know how dead you are.”

“I’ve been practicing,” I said.

No heroics. Nothing that would make an ER tech whistle. Just enough to put a sunrise’s worth of lesson into his body. When he stopped trying to be taller than my resolve, I zip-tied his wrists behind the seat of his precious car, ran duct tape from his chest to the headrest like a seatbelt for poor choices, rolled all the windows down, and turned the heat to a setting that would make Satan sweat.

Then I introduced an old fisherman’s secret to German engineering. A five-gallon bucket of raw shrimp under the dash and in the air vents. I can’t tell you who sold it to me; I didn’t pay with a receipt. It made a sound like a thousand tiny doors closing. The smell hit first—a promise of what August does to the coast if you forget to ice the cooler.

“By the time someone finds you,” I said, “this car will smell like an apology you can never scrub out.”

I took his phone and snapped three pictures: the bruised knuckles, the duct tape sash, the shrimp tails like confetti. I posted them to his accounts with captions he would never write: Tough day at the office. Always wear your seatbelt. Seafood special. Then I tossed the phone on his lap and walked out of the alley whistling a tune my mother used to hum when she knew she’d won an argument.

By noon, half the county had seen the great Grant Morrison trussed like Thanksgiving, his Mercedes marinating in humiliation. The other half knew somebody who’d seen it and was willing to do a dramatic reading over coffee. Fear doesn’t like to be laughed at. Laughter weakens knees.

I went downtown and parked where the sun hits glass and makes men look like ads for themselves. At ten, the doors of Cal’s building swung open and there he was, flanked by two new muscles whose suits fit like debt. The sidewalk crowd parted the way it does for people who have power or teeth. He scanned, found me leaning out my truck window, and smiled a smile that had bought a lot of silence.

I waved like a neighbor on a tractor. “Beautiful morning, Cal,” I called. “Smells like the ocean.”

His jaw worked. He said something to the guards. They decided their retainer didn’t include assault in front of witnesses and cameras. They grazed him toward the curb. He left without answering the weather.

He wasn’t the only visitor.

Melanie came to Pete’s cabin two days later, wearing a maternity dress that tried too hard and a face that couldn’t keep up. The bump had introduced itself to the world. She stood on the porch and looked smaller than excuses make you.

“Tom,” she said. “We need to talk.”

“Nothing left to say,” I said without standing. “You made your choice. I made mine.”

“You can’t keep doing this,” she said. “You’re going to get yourself killed.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But not tonight.”

“Cal’s lawyers—”

“Cal’s lawyers can kiss my ass,” I said, and felt Pete’s posture shift behind the screen like a man trying not to smile.

She looked down at the boards as if they might vote. “You don’t have to be cruel.”

“Says the woman who said ‘work husband’ with our mortgage in her mouth,” I said. I pulled my phone and showed her a screenshot Jenny had texted me like a trophy: Melanie and Cal kissing in the back lot of the Riverside Motel, timestamped in unfortunate daylight. The comments had sprouted like weeds.

Jenny has many sins. Forgetting is not one of them. “She’s been paying attention,” I said. “Amazing what the town’s eyes notice when you treat them like they’re blind.”

“This isn’t going to work,” Melanie said, but for the first time in our married life she didn’t sound like she believed herself.

“It already is,” I said. “Go home.”

She stood there a long minute, hand resting on the scaffolding of a future I wasn’t building with her. Then she turned and went down the steps. I watched her put one hand on the small of her back without thinking. Biology keeps its own counsel.

That night somebody threw a brick through Pete’s front window. The note wrapped around it said BACK OFF in block letters that tried to be brave. We swept glass to the rhythm of men who have done it before. Pete held up the paper like it was a fish that didn’t deserve to be mounted.

“Subtle,” he said.

“Desperate,” I corrected.

He nodded. “Desperate men do stupid things.”

“So do lazy ones,” I said. “Time to trim some rot.”

The next phase didn’t require bats or buckets. It required paper and a man with a spine for it. Danny Sullivan had been writing the kind of stories that get you uninvited from fundraisers for ten years and looked exactly like you think: sleeves rolled, tie a rumor only, hair with a permanent part from leaning into public records. He met me at a diner off Route 7 where the waitress didn’t bother to hide the way she listened.

“What’s your angle?” he asked after the coffee.

“Accountability,” I said.

“That’s not a headline,” he said.

“It will be after you’re done,” I said. “But we do it right. No cowboy. No anonymous slander. Paper. Records. Names. You don’t publish what you can’t footnote.”

His eyes warmed. We talked structures. We talked bids that always went to companies who happened to sponsor the mayor’s golf tournament. We talked shell LLCs that all filed from the same P.O. box next to a failing tanning salon. We talked about a councilman’s brother-in-law who kept winning projects three dollars under the competition and about a school gym with a roof that leaked five months after the ribbon cutting.

Danny brought the diligence. I brought the maps. We built a case the way you build a staircase you plan to run up and down the rest of your life—each riser the right height, each tread the same depth, nothing that would make a foot miss.

While we worked, I salted the town. Anonymous tips to the county paper about “process questions.” Public comments at council meetings spoken in the measured voice I used when clients wanted another modification for free: “Do we have an audit for that?” I didn’t accuse. I asked. Questions, it turns out, can be levees when the flood wants to be a fire.

Grant avoided Mickey’s for a while. When he reappeared, men only laughed when his back was turned. That hurt him more. Fear ages quickly when it isn’t fed. Cal kept showing up at places that used to belong to him by presence, not deed, and discovered that attention and respect look the same from ten feet away but feel different in the chest.

And then the paper hit.

It was a Thursday. The front page was all caps and clean font: MONEY, POWER, AND FAVORS: A DUNSTON PLAYBOOK. Danny’s byline under it like a dare. Inside, three pages of the kind of journalism that makes people cancel subscriptions and new people buy them. We hadn’t used the word corruption. We didn’t have to. We had charts. We had checks whose memos read like jokes: CONSULTING – THANK YOU. We had dates. We had emails where “just making sure our friends are taken care of” was sent from a city account.

By noon, the attorney general had announced a preliminary inquiry, which is what the state calls it when it wants to flex without leaving fingerprints yet. By evening, the local news had parked a van on Main Street and interviewed people who always wanted to be interviewed and one woman who looked straight into the camera and said, “I don’t owe men like that my silence.”

Cal lost a contract by lunchtime, another by sunset. Three council members issued statements that said “integrity” a lot. The school board scheduled a “budget transparency night” which is code for “please don’t yell at us in Aisle Five.” Grant’s Mercedes was for sale online for an insultingly low number with the description needs detail.

Melanie stopped calling. Sasha posted a quote about resilience with no punctuation. Jenny texted me at 11:04 p.m., because gossip keeps office hours but news does not: Heard Cal moved into the two-bedroom over Dunlap Hardware. Mrs. D gave him a discount on paint but told him to carry the cans himself.

Pete snorted when I showed him. “We might make a decent town out of this one yet,” he said.

It should have felt like winning. It felt like clearing land after a fire: the work just different now.

In the middle of all that noise, something else happened that I held to my chest like a secret: I slept through the night. No coyotes pacing the edge of my memory. No headlights strobing my brain. Just dark, then morning. When I woke, the house didn’t float. It sat. That’s what foundations are for.

A week later, Cal walked past me in the grocery store. He pretended to read labels of things men like him hire other people to buy. I pretended to compare prices on paper towels I’d always loved for their lack of drama. Our carts passed with the intimacy of strangers who used to be enemies. He didn’t speak. I didn’t either. Silence, in small towns, can be a message. I wanted mine to say: You don’t live here anymore.

The brick-thrower tried once more at Pete’s. This time it came wrapped not in a threat but in pity: YOU’RE MAKING IT WORSE FOR HER. I didn’t need to ask who her was. I folded the paper in half and put it under a magnet shaped like a lobster on Pete’s fridge.

“Souvenir?” he asked.

“Reminder,” I said. “Rescuers often look like captors on paper.”

“Just don’t drown yourself trying to be the lifeguard,” he said.

I pointed to the lists spread on his table. “No one drowns with this much lumber to cut.”

The calls that followed weren’t threats. They were confessions. A mechanic who’d been stiffed on a big fleet job because Cal’s man wanted a “consulting fee” in cash. A diner owner who’d been told to “be a team player” if she wanted her permit renewed before tourist season. A school custodian who’d been instructed to “lose” an inspection report. None of them had wanted to be first. Now none of them wanted to be last.

Danny worked late. Powell—the assistant DA with a reputation for teeth—started showing up in rooms and asking for sworn statements. The mayor held a press conference and said “we welcome scrutiny,” which is the sentence politicians put in their mouths when their hands are cold.

Jenny baked a casserole, because even when we hurt each other we feed each other. She brought it over with a look that said I told you so and I’m proud of you and I want to be the first to know about anything new. “You didn’t hear it from me,” she said, which is Jenny for I’m about to tell you, “but Cal’s wife is lawyering up like she’s about to go on a cruise.”

“Good for her,” I said, and meant it.

That night, sitting on Pete’s porch with the kind of comfortable quiet men get when they’ve shared enough words, I ran my thumb along the bat’s grain and thought about wood. People think the important part of a bat is the swing. It isn’t. It’s the balance. It’s where the weight lives. You lift, you let gravity do some of the work, you meet what’s coming with what you’ve built.

“What’s next?” Pete asked.

“Paper did its job,” I said. “Now we make sure he can’t talk his way back into rooms.”

Pete nodded at the dark. “Rooms have long memories,” he said. “People forget. Chairs don’t.”

I didn’t answer. Somewhere a car door shut. Somewhere a dog decided to guard something that didn’t need guarding.

I slept again.

In the morning my phone lit with a text from a number I recognized by the way my stomach didn’t: We need to meet. Alone. Cal. I could’ve ignored him. I could’ve sent the text to Powell and let her salivate. Instead I stared at the word alone until it split into what it usually means for men like him: control.

I typed back: Old Griggs Mill. Sunset. No entourage, no lawyers. The mill had been dead longer than my business had been alive. Steel ribs, broken windows, graffiti that managed to be both ugly and honest. It felt right.

Pete read over my shoulder and didn’t argue. He just cleaned his shotgun and leaned it against the wall as if he were putting a picture back where it belonged. “I’m not five miles from you,” he said.

“I know,” I said.

On my way out, I stopped by the house on Griggs Mill Road. The porch I’d left half finished for two years had been waiting for me, like a dog that forgives quicker than it should. I carried two planks to the sawhorses and cut them just because I could. The sound steadied me more than prayer.

“Finish it,” I told the boards. “We’ve got people coming over eventually.”

By the time the sun started making deals with the trees above the mill, I knew what I wanted to say. I also knew I didn’t care if he heard it.

I parked under a busted light. The building breathed old dust. A bird had made a nest in a rafter and didn’t ask our permission to live. Cal pulled up in a sedan that used to be a joke and was now a sentence. He got out like a man remembering how weight works.

“You wanted to meet,” he said.

“I wanted you to feel what it feels like to come when someone else asks,” I said. “Men like you don’t practice that enough.”

He tried a smile. It cracked. “What do you want, Tom?”

“An apology,” I said. “And an audience.”

He squinted toward the doorway. “You streaming this?”

“No,” I said. “Not yet.”

He exhaled, some of the tightness leaving his shoulders. “You’re thorough. I’ll give you that.”

“I learned from the best,” I said. “How to keep records. How to post the right picture at the right time. How to make a room remember a smell.”

“Grant is furious,” he said.

“Grant should learn to love Febreze,” I said.

Cal laughed once. It sounded like something falling down a well. “You think you’ve won, don’t you?”

“I think I stopped losing,” I said.

He looked around the ruin like it was a church and he was finally honest in it. “Men like me don’t stay down.”

“Men like you don’t know how to live without someone else’s name in your mouth,” I said. “That’s the difference.”

He stared at me for a long time. Then he said, “Turn it on.”

“What?”

“Your camera,” he said. “Turn it on. Let them see.”

I don’t know if it was guilt or exhibitionism or a last good business instinct. It doesn’t matter. I took out my phone and went live.

“Evening,” I said to the dot that meant half the town would be watching by the time I finished the sentence. “Here’s the man who taught me that documentation is a love language.”

Cal straightened like a man trying on a smaller suit. He opened his mouth and for the first time since the rooftop party in spring, I wanted to hear what would come out.

But that’s a story for tomorrow.

Part Three:

There’s a particular feeling when you go live and know half the town is already leaning over their kitchen tables to watch. It’s like stepping onto lumber you milled yourself: you trust it, but you still listen for the creak.

The blue dot blinked. The view counter jumped—forty, eighty, one-fifty—names blooming like wildflowers and weeds. Jenny Morrison: oh my god. Danny Sullivan: recording and screen-capping. Powell, ADA: 👀. Even the church youth pastor: keep it civil, fellas. The scroll took care of itself.

Cal turned slightly toward my phone, then squared to me like he’d finally realized the only way through was straight. He looked smaller in the mill’s ribs than he did in glass lobbies. Power loses height without ceilings.

“You asked for this,” I said, the camera steady in my hand. “So let’s give them the courtesy of names. You are—”

“Calvin Dunston,” he said, jaw tight, like he was strapping on a helmet. “And you’re filming me without counsel.”

“You don’t need counsel to apologize,” I said. “Let’s start there. For the affair. For the beating. For the way you turned a town into a vending machine.”

He laughed once—the reflex of a man who’s been taught that noise is armor. Then something in his face relaxed, like he’d just heard his own echo.

“Tom,” he said, and there was a human in it, “I will not pretend I wasn’t wrong. I won’t pretend I didn’t tell Grant to… teach you a lesson.” He took a breath that made his suit hang wrong. “I didn’t tell him to leave you in the woods. That wasn’t my instruction. Does that matter to you?”

“In court?” I said. “Maybe. In the story of who we are? Not much.”

The comments fluttered like birds startled by a door. he ADMITTED it— print the t-shirt call the AG teach you a lesson??!! men like this always got ‘lessons’.

Cal glanced at the phone like he could unsee it by wanting to. “You want me to say I’m sorry,” he said, older than his hair dye. “Fine. I’m sorry.”

“To who?” I asked.

“To you,” he said.

“And?”

He rolled his eyes. “To your neighbor’s Facebook feed?”

“To my ribs,” I said. “To Old Pete’s window. To my porch. To the town clerk you made cry in her own office when a permit didn’t slot into your timeline. To the teachers who watched the roof leak on kids and had to pass the bucket like communion because you hired your friends. To my wife you treated like a raffle prize, even if she ticketed herself.”

He swallowed. For a second, I saw the boy he’d been—sharp, scared, learning the wrong lesson from applause. “I’m sorry,” he said, louder this time, to the rafters, to the lens. “I’m sorry to the town. I’m sorry to the men and women I used like furniture. I’m sorry I thought fear was respect.”

The live feed lit. ❤️❤️👍. did you hear that?? somebody screen grab this is wild my aunt worked his fundraisers—he made her stand on tiptoe to look taller in pics! Powell—are you seeing this?

The ADA’s little eyeballs stayed on the corner of my screen like a lighthouse.

“Good,” I said. “Now for the part you think you can bargain with.”

He stiffened, reflex back. “I won’t give you a list of names.”

“I don’t need your list,” I said. “Danny has paper. Powell has subpoenas. I need your face when you say the words: I thought I owned this town.”

He stared at me, then into the phone. He wasn’t good at silence; men like him hire other people to stand in it for them. When the beat stretched a hair longer than comfortable, he said it.

“I thought I owned this town.”

“And now?”

“And now I live over the hardware store,” he said. “And carry my own paint.” His mouth skittered sideways—something like a smile, something like a muscle twitch. “Turns out people will still sell you things if you’re polite.”

“It’s almost like being decent works even without a retainer,” I said.

He shrugged. “You learn fast when you run out of shortcuts.”

I let the chat fill with its confetti. I wanted the town to sit in a feeling it hadn’t had in months: gravity returning.

Behind the lens, I let myself relax my shoulders half an inch. I could have ended the video there and called it a public service announcement: Rich man discovers consequences; film at eleven. But a part of me—the carpenter, not the crusader—wanted to leave the room better than I found it. That meant not just tearing the rot but bracing the beam.

“Cal,” I said, soft enough the microphone still had to work for it, “what do you think you were building?”

He blinked. The question knocked him off the script. “A business,” he said. “A platform. A name that made other names want to be near it.”

“And all you built was a wall between you and how people tell you the truth,” I said. “You board up enough windows, pretty soon you start believing your own light.”

He considered that. “You’re a contractor,” he said. “Do you talk like that on bids?”

I smiled despite myself. “Depends on the job.”

He nodded once, like a man conceding a point without surrendering the game. Then, because habit is a spine even when you’re trying to grow a new one, he looked back at the phone and addressed the town like it belonged to him a little still.

“I’m not asking for sympathy,” he said. “I know the difference between sympathy and a second chance. I’m asking you to stop looking at me like a monster you kept in your basement for entertainment. You liked what I did when it made your festival bench show up on time. You clapped when I sponsored your kids’ jerseys. We all did this. I just did it bigger.”

The comments split: he’s not wrong don’t let him spin we all went to those banquets but he took the money who wrote that line for you, Cal this is the most Maine thing I’ve ever seen.

He’d found his footing for a second. I let him. A good fall needs a few steps.

“Do you have anything else to say?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Tell Grant I won’t be needing his services anymore.”

“You could tell him yourself,” I said.

He looked pointedly around the mill. “I suspect he’s watching.”

The comments agreed in a chorus of shrimp emojis.

I ended the feed. The silence that followed felt like an empty church after a wedding—perfume and expectations and the sudden echo of your own shoes.

My phone buzzed before I could slide it into my pocket. Powell.

Do not move. Then: Actually, move. But to a public place with people and cameras. We’re sending someone to take a statement. Also, don’t get yourself shot.

I thumbed back: Hardware store? Three blocks.

Fine. Buy duct tape. Symbolic. A beat. And gauze. For next time your decisions think with spite before skin.

I snorted. “ADA with jokes,” I said to Cal. “We’re to go where the cameras are.”

He looked at me like I’d asked him to lift something with a part of his body that had always hired a personal trainer. “Tom,” he said, the human leaking again, “I meant what I said. I didn’t tell them to leave you there.”

“I heard you,” I said. “Now hear me: don’t ever talk to my wife again.”

“She left you,” he said, a flash of the man who never misses a blade. “She wasn’t your wife by the time—”

My hand moved before my brain had a chance to send white flags. Not a swing. Not a shove. Just a very firm index finger in his direction, like we were two boys behind a shed and the school bell had rung.

“No,” I said. “No more sentences that start with She. Not from you. Not about my life.”

We walked out under the busted light together, two men doing something neither of us had been trained for: carrying our own weight.

By the time I reached the hardware store, the sidewalk looked like Main Street on the Fourth minus the hot dogs. A crowd had that respectful distance people keep when they want to be close enough to say I was there but far enough to say I didn’t shove. Mrs. Dunlap herself stood behind the paint counter with her receipt book like it was a gavel.

“Duct tape,” I said, laying a roll of silver on the counter. “And gauze.”

“You boys need rope?” she asked dryly.

“No ma’am,” I said. “We’re trying conversation.”

Powell arrived with a junior investigator who looked like he’d learned to shave by reading a manual. She took me by the elbow like a nurse and led us to the office behind the key machine. “You just handed me an admission on a plate,” she said. “Not the felony kind. The we’re going to make your lawyer work for the settlement kind.”

“I’m not trying to hand you anything,” I said. “I’m trying to hand the town a mirror.”

“Sometimes the mirror is evidence,” she said. “You okay?”

“Define okay,” I said.

“Do you need a hospital?”

“No,” I said. “Just maybe some ice and someone to tell me I’m not insane.”

“You’re not insane,” she said. “You’re dangerous.”

“Only to men who think boot heels are furniture,” I said.

She smiled, then straightened as her junior handed her a paper. “Grant Morrison,” she said, scanning. “Picked up on a bench warrant at the mall. Security gig didn’t come with ‘get out of jail’ card.”

The room shifted—not a cheer, not a sigh. Something like a town letting out air it had been holding in a long time.

“And Melanie?” I asked before I could train myself not to.

Powell’s face did something complicated. “She’s not my office’s problem,” she said. “She’s yours.”

“No,” I said. “She forfeited that jurisdiction.”

“Even so,” Powell said gently.

It took two days for the mill video to make the state news and five for the AG’s office to formalize the inquiry into no-bid contracts. The council scheduled a “listening session” that would involve few ears and many microphones. Cal’s wife filed for divorce on the courthouse website like a person ordering takeout. Grant posted bail, then deleted all his social media, which made the shrimp pictures spread more out of spite than before.

I drove back to the house on Griggs Mill Road and finished the last three runs of railing on the porch. Stain makes everything look intentional. I sat on the top step with a beer and the particular throb in my hands that says today, you made something tangible. The sun did that trick where it finds the one nail you didn’t set quite deep and turns it into a lesson. I made a note to tap it down tomorrow.

Jenny’s text arrived like a doorbell. Heads up: Mel on your sidewalk. She added three emojis I won’t describe because sometimes she’s twelve.

I didn’t move. I didn’t have to. The steps put me higher than the yard; she had to climb to me.

She came up slow, a hand under her belly the way women do without thinking when a hill gets steeper. She’d traded sharp lines for practical clothes and high heels for flats. Sasha hovered at the curb—the kind of friend who wants to say we when she means tell him the thing for me, too. Melanie reached the top board and stopped like she’d discovered she’d been saying my porch about something that had always said ours until it didn’t.

“I need to talk to you,” she said.

“You’ve said that before,” I said. “It didn’t go great.”

Her eyes were red in a way mascara can’t fix. “Call off Powell,” she said. “Call off your videos. Call off whatever crusade you think this is.”

“It’s not a crusade,” I said. “It’s carpentry. I’m pulling nails and replacing rotten beams.”

“You’ve made me a pariah,” she said, voice shaking. “I can’t get hired. Sasha’s landlord wants her out because of me. People cross the street. They whisper. I can’t go to the diner without Jenny performing a one-woman Greek chorus in booth five.”

“Then move,” I said. “Or sit through it until it shrinks. But don’t ask me to lie still for you again.”

She put a hand on the railing I’d just sanded. “I’m pregnant,” she said.

“I noticed,” I said.

“Whatever you think of me,” she said, and there it was—the old sales pitch trying on humility like borrowed linen—“this baby doesn’t deserve your scorched earth.”

I felt my jaw set the way it does when a nut refuses to thread and you know if you force it you’re just buying trouble later. “I’m not salting anything,” I said. “I’m planting stakes so people know where the edge is.”

“Help me,” she said. “Please.” The please sounded like a foreign language word memorized for a test: correct, heavy, without music.

“Help you how?” I asked.

“Talk to Powell,” she said. “Tell the paper to stop. Tell Danny to write about something else. Tell Jenny to stop—”

“I don’t tell Jenny anything,” I said.

“Tell the town you forgive me,” she said, and her voice broke on forgive the way a shelf breaks under a weight you pretend is lighter.

“And then what?” I asked. “We take a picture for your feed? We teach the town not to bother noticing because there will always be a statement later with a tasteful filter?”

She flinched. “We grow up,” she said. “We move on.”

“You moved on when you put his hand on your back and called him your husband with my name still in your mouth,” I said. “You moved on when you laughed in our kitchen and said everyone wins.” I shook my head. “No, Mel. I’m not your PR department.”

She stared at me for a long beat, then did something that was almost worse than fake: she told the truth.

“I’m scared,” she said. “He’s not returning my calls. His wife froze all his accounts. Sasha’s couch has a ridge in the middle. People are… crueler than I predicted. And if I have this baby in a town that only knows me as a headline, it’s going to learn that story before it learns my name.”

I looked away because looking at a crying pregnant woman you used to love is how men make bad decisions for the right reasons. The field across the road had just been mowed. The line between rough and smooth was clean as paint. The house—my house—smelled like stain and sawdust, the two scents I trust more than any cologne.

“I’m not going to punish a kid for its parents,” I said. “I’m not signing a birth certificate for a baby that isn’t mine. I’m not showing up in pictures that tell a lie. But when that kid needs a crib, there’ll be one on this porch with its name carved in the footboard if you want it. When it needs a roof patched, I’ll show up with shingles if you ask. The rest? No.”

She blinked like she’d prepared for a different kind of refusal. “You’d… make a crib?”

“I build things,” I said. “It’s what I do.”

She let out a small sound—a laugh that had remembered how to be a laugh—and then covered her mouth like she’d just broken something in a museum. “Thank you,” she said, a phrase I’d heard from her before but never believed. This time it sounded like it had been earned by someone else and she’d borrowed it. She started down the steps, then turned back.

“Tom?”

“What.”

“You were never small-time,” she said, almost to herself. “I just didn’t recognize the kind of big you were.”

She left. Sasha’s car swallowed her whole and peeled away with the kind of urgency cowards call commitment.

I sat there a long time. The sun shifted and the porch’s shadow crawled across the yard like a tide that had decided to come back after all. A kid rode by on a bike with a baseball card rattling in the spokes and made the sound of June.

My phone buzzed. Powell again. Grant arraigned. Judge denied his passport request. Cal’s counsel looking for a deal. Also: That crib offer? I didn’t hear it. But I did. It was good.

I set the phone down next to the beer, which had gone warm but tasted like a promise anyway. I ran my palm over the new railing. Smooth. No splinters. Tomorrow I’d hang screens. Next week maybe I’d finally paint the house the blue I’d been telling myself we’d do someday.

Love doesn’t survive splinters, but people do. Houses do too, if you keep your hands honest and your nails straight.

I finished my beer and listened to the town make small, kind noises that didn’t require witnesses. Somewhere, in a tiny apartment over the hardware store, a man who used to own everything was learning how to sleep without applause. Somewhere, a woman who’d traded her soul for a promotion was trying to calculate the price of a crib made by the man she hadn’t believed in. Somewhere, Jenny told the story of what she’d seen and left out the parts that didn’t make her look generous. Somewhere, a baby kicked, which is another way of saying the earth rotates.

The wind shifted. It smelled like rain without the threat of it.

Tomorrow I’d buy maple and a new set of chisels. I had a crib to build.

At The Work Party, My Pregnant Wife Leaned Over To Her Boss & Said, “He’s My Work Husband,”

Part Four: The Crib, the Courtroom, and the Clear Ending (≈1,900 words)

Maple takes a mark the way truth takes a room—clean if your tools are sharp, ugly if you rush. I bought eight-quarter boards from a mill up in Weld and spent a morning picking through stacks the way a man picks through memories. You want straight grain for rails, something with a little figure for the headboard. Maple smells faintly sweet when it gives, almost like it’s forgiving you for all the pine you settled for when you were a kid.

I jointed the edges, planed to thickness, and laid the pieces out on sawhorses like a map of something I finally knew how to get to. Pete showed up with coffee and a donut he swore wasn’t from the gas station even though the glaze told on him.

“You’re really doing it,” he said, running a thumb along the future footboard.

“I said I would,” I said.

“Men say a lot of things,” he said. He didn’t mean it sharp. He meant: There are, still, some we’ll keep.

I cut mortises for the rails, chiseled tenons, dry-fit the headboard. No screws. No shortcuts. You build something a baby will sleep in like you’re asking the future to trust you. I rounded every edge. Splinters teach hard lessons; this child would not have to learn mine with blood. Inlaid a small coin-size circle at the center of the headboard—not a heart, nothing corny. Just a knot taken from a piece of maple that had grown against wind and lived to tell about it.

“You going to carve a name?” Pete asked.

“Not mine,” I said. “Not his either. Just the initial. When they pick one.”

“And if they don’t tell you?” he said.

I shrugged. “Then it can wait.”

By evening the frame stood without glue, a set of clean lines in a shop that smelled like work. I sanded until my shoulders asked for mercy and rubbed the pieces down with an oil that brought out a soft amber. The wood drank it like a field in July. That night I dreamed of railings that stayed where I put them and doors that shut with soft clicks. I woke with my jaw unclenched.

Two days later, the courthouse felt smaller than it should, like a place that knew it had more gravity than square footage. Powell met me on the steps with a file under her arm and a look that wasn’t unkind.

“Today isn’t fireworks,” she said. “It’s paperwork with teeth.”

Inside, the clerk read names with the monotone of someone who has learned not to absorb stories through sound. “State v. Dunston,” she said, and the room sat up a little.

Cal wore a suit that was almost the same color as the last one, which is to say not at all the same since context does more work than fabric. His wife was not there. His lawyer looked like a man who enjoys good bourbon and hates clients who talk to cameras.

“Your Honor,” the lawyer said, “my client will enter pleas consistent with the agreement on file.”

The judge—older, glasses halfway down his nose, hair doing its own quiet protest—looked over the top of the frames. “Mr. Dunston, do you understand the charges to which you are pleading?”

“Yes,” Cal said, voice catching on the s like it had found sand. “I do.”

“Say the words,” the judge said, not unkindly. “The record needs them.”

“Guilty,” Cal said to the first—a count tied to campaign finance filings that had played connect-the-dots between his companies and a slush fund with a patriotic name. “Guilty,” to the second—bid-rigging in the form of “consulting agreements” that looked like envelopes in better clothes. “No contest,” to a misdemeanor count rolled up with the rest, language that would never mention me but knew my name.

The judge nodded. “The state has argued for restitution, fines, prohibition from bidding on public contracts for a period, community service, and a course of ethics. Ms. Powell?”

Powell stood with a stillness that had dented bigger men than me. “Your Honor, we ask for five years’ prohibition on contracting, audited restitution to the town, two thousand hours of community labor not connected to any organization he previously funded, and a written statement in open court naming what he did. We’re not in the business of buying apologies with checks.”

“Mr. Dunston?” the judge said.

Cal looked down at his hands, spread them on the table, and—choosing, finally, not to perform—said, “I did this. I made a habit of treating rules like suggestions for other people. I made convenience my ethics. I’m sorry.”

“You are also barred,” the judge added, “from contacting Mr. Crane in any manner, directly or through others, for the length of your probation. If you need a mirror, buy one that doesn’t talk back.”

A small laugh moved through the benches and died when the judge put a finger on the air.

“Mr. Morrison,” the clerk read next.

Grant came in shackled, still big but smaller somehow—like the room had done math on him and found him less than the sum of his threats. He had plead to assault and to a menacing charge. His lawyer said a lot of words that sounded like water around rocks. The judge listened, then looked at me.

“Mr. Crane, do you wish to be heard?”

I stood. The room smelled like paper and old coffee. “I’m not here to ask for a number,” I said. “That’s what the law is for. I’m here to ask for two things: keep him away from me, and make sure the next man a boss like Cal points at doesn’t think this job description includes breaking people for sport.”

The judge nodded once, a carpenter noting a level wall. He sentenced Grant to eighteen months with six suspended, probation, anger counseling, and the kind of working day that would introduce him to litter along Route 4 in July. He added a “no contact” order that would play, if violated, like a sharp chord.

“The state thanks you,” Powell said when we stepped into the hallway. She meant for not lighting a match when gasoline was handy.

“I’m just trying to live in a place where men don’t get to teach each other lessons with fists,” I said.

“That’s policy,” she said. “We do statutes. But sometimes they hold hands.”

On the way out, Danny pushed his glasses up and asked for a quote. I gave him one sentence—“Documentation matters”—and told him to spend the rest of his ink on the women at the permit office who had been bullied into silence and then found their voices again. He nodded, pen flying.

Outside, fall had deepened. The trees along Main Street were halfway between green and the kind of red that makes your chest hurt. People stood in small groups saying smart and dumb things with equal conviction. This is what towns do: metabolize.

I went home and put the last coat of oil on the crib. The grain came up like a tide. I added one detail no one would notice—the faintest bevel at the top of the headboard, a place for a parent who hadn’t counted on this to rest their forearms in the dark. I carved a small initial on the underside of the right slat: a J, because that’s what the world keeps naming kids when it hopes for a better century. If Melanie chose a different letter, I could plane that one off and start again. Wood is generous when you know where to ask.

I moved the crib into the living room and stood looking at it like a man who had built something that wasn’t about him. It looked steady. It looked kind.

Jenny arrived without knocking, carrying a casserole and three questions I didn’t answer. She stood in the doorway and got quiet in the way people do when objects rearrange their ideas.

“You’re really going to give it to her,” she said.

“I said I would,” I said. “I’m trying to make a habit of the right promises.”

She set the food on the counter and, for once, didn’t perform a monologue. “You know,” she said finally, “for all the things you can say about men in this town, they know their way around a crib.”

“I’ll take that as a compliment,” I said.

“It is,” she said. Then she ruined the moment in the most Jenny way possible. “Also, Sasha says Melanie’s been craving pickles and ice cream like it’s a sundae bar. I told her that’s not a personality.”

“Goodnight, Jenny,” I said, and she laughed herself out.

We carried the crib to Pete’s truck at dusk, the two of us moving slow, corners first, the way you learn to move things that matter. I’d called ahead. Sasha answered and said Melanie was home. Her voice sounded tired, which is different than exhausted. Tired is what you feel when you’re learning humility.

They lived now in a small apartment over a nail salon that made the whole block smell like acetone and dreams. Sasha opened the door, hair up, eyes softer than I’d ever seen them. Melanie stood behind her, belly high, one hand on the small of her back in that automatic way that makes men forgive themselves for things they didn’t say.

We set the crib down against the far wall in a room that had two lamps, a couch rescued from a curb, and a hopefulness trying not to be embarrassed. Melanie reached out and touched the headboard like a person reading a name on a monument.

“You did this,” she said.

“I build things,” I said.

She turned a little, enough to show me something new in her face. Not gratitude exactly. Recognition. “We decided on a name,” she said. “June. Like the month we stopped pretending.”

“It suits a crib,” I said. “J is already in there.”

She blinked, and I watched her swallow the thing I didn’t need to hear: thank you. Some words grow heavy if you make them do too much work.

I ran a hand along the rail to give myself another second to believe the room. “Listen,” I said, “boundaries are the only way this works. I’m not putting my name anywhere it would tell a lie. But when you need a hand you can ask. When June needs something, and it’s made of wood or work, you can call. That’s it. That’s all.”

Melanie nodded, both hands on the belly now. “I was going to ask you to stay,” she said, honest enough to hurt. “Look at it when she goes to sleep. But… that’s for later. For someone else.”

“I’ve seen enough rooms that weren’t mine,” I said. “You’ll be fine.”

On the way out, Sasha squeezed my arm. “You didn’t have to,” she said.

“I know,” I said. “That’s why I did.”

Winter cut in hard that year, early frost turning fields into tabletops. Cal’s community service vest became a local sighting; people pretended not to stare. My business hit a strange sweet spot. Folks who’d avoided me for fear of choosing sides now called because their houses needed work, and a man who had made a town stare into a mirror might as well square a door while he was there. I hired two more guys. I taught them how to bury nails in finish work so future palms won’t catch.

Grant disappeared into the system and reappeared on the roadside with a grabber stick, and I didn’t slow down when I drove past. Some lessons don’t involve eye contact.

The council passed new procurement rules with language so plain even men who liked loopholes would have to find a new hobby. The school patched the gym roof and held a spaghetti supper that tasted better than fundraisers usually do. Powell sent me a Christmas card with a cartoon gavel on it and a note: Keep your hammers. We got these. Danny’s series won a statewide award and he used his two minutes at a podium to thank the janitors who had shown him the back hallways where the signatures lived.

In January, an envelope showed up with the county seal. It wasn’t a summons. It was simpler: a check and a letter from a restitution fund. I endorsed it and walked it into the shelter downtown because I’ve learned the only good way to spend money earned off pain is to end someone else’s. The director hugged me the way people from grant committees never do and asked if I’d build a bookshelf for the kids’ room. I did. I carved a small J inside the bottom shelf where no one would see it and anyone could feel it.

Early March, my porch saw its first thaw puddle. I sat on the top step with a coffee and watched my breath cut the air into rectangles. An SUV pulled up across the street. Melanie got out, wrapped to her eyes, carrying a bundle the size of a bowling ball and about as heavy with consequence. She didn’t come up. She didn’t wave for me to come down. She stood at the curb and lifted the blanket one inch and let me see a soft, sleeping face with a mouth set in a line that had never had to unlearn being spoken over.

“June,” she said, just loud enough.

I didn’t say she looked like anyone. Babies look like possibilities. I nodded, then pointed to my chest, then to the house, then made the universal carpenter’s sign for call if something breaks. Melanie smiled like a person who has accepted an adult’s version of a truce. She put the baby back in the car with a care I’d never seen her use on jewelry.

When they drove away, I went inside and called Pete. “Come by,” I said. “Bring the good coffee this time.”

He did. We sat. We didn’t say much. Men don’t need a lot of dialogue when they’re not keeping score anymore.

“House looks done,” he said after a while.

“It’s never done,” I said. “But it’s standing.”

He tapped the railing with two fingers. “You’re all right, Tom Crane.”

“I’m getting there,” I said.

He left. Evening fell in a kind way. I turned on the porch light. The switch clicked, the bulb warmed, and the pool it made on the steps looked like an invitation even if no one knew they were invited.

That night I slept in my own bed and dreamed nothing, which is a kind of miracle they don’t teach you to ask for.

Spring came in stubborn. The river swelled, then remembered its banks. The town learned a new rhythm: fewer whispers, more names. If you passed the hardware store and looked up, you saw a man hauling his own bags of mulch down the back stairs. If you ate at the diner, you sometimes saw two women split a plate and an apology without anyone writing think pieces about it. If you drove out past Griggs Mill, you saw a blue house with a finished porch, a swing hung true, and a set of chisel marks on a crib drying in an upstairs room you couldn’t see.

On a Saturday in May, I threw a cookout, because men like me have to practice celebration the way we practice cutting straight—slowly, with patience, letting the tool do the work. I set up two tables, one for food and one for stories, and asked people to bring the second one in pieces and set them down without heat. Pete came with PBR and ribs. Jenny came with a new haircut and a promise to behave she almost kept. Powell showed up in jeans, which made three men forget how sentences end. Danny toasted the freedom of the press with ginger ale. A couple I’d built a sunroom for brought pie and didn’t ask questions. A woman from the shelter hugged me twice. The only children on my lawn were the run-and-yell kind, which is exactly the number you want.

Near sunset, a car slowed at the curb. Melanie didn’t get out. She rolled down the window and lifted June so the baby could see lights and people and the way a small town looks when it’s being kind to itself. I lifted my hand in a small salute and felt, finally, the thing I had been building toward without knowing: the moment when forgiveness isn’t a door you have to choose to walk through or not, but a porch light you will always leave on for the parts of the future that can find their way by it.

The grill hissed. Someone yelled for ketchup. Pete sat on my steps with a plate and didn’t spill barbeque sauce on my new stain. The wind came up and then went back to wherever it sleeps. I looked at my hands. They were scarred in the normal ways. They were clean.

Love doesn’t always survive betrayal. Marriage didn’t. That house of cards is compost now. But I learned something better than forgiveness, something sturdier than revenge: how to keep building after the wind changes. How to set posts deep enough that storms make noise and then pass. How to take a story that tried to make me the lesson and turn it into a room where other people can breathe.

When the last guest left and the yard was back to its old grammar, I turned off the porch light and stood in the dark a second longer than necessary, just to prove to myself that I didn’t need applause to know what held me up. Then I went inside, checked the lock with the soft twist I like, and went to bed.

In the morning, I’d cut stock for a bookshelf. After that, maybe a small table for a woman down by the river who’d asked for something “sturdy but pretty.” The news would do what it does. The town would hum. June would sleep in a crib built by a man who finally learned the difference between not losing and living.

And me? I’d wake, measure twice, and keep going.

The End.

News

Cheating Wife Packed Her Stuff And Said, You Didn’t Want To Open Our Marriage So I’m Taking The Kids… CH2

Part I At twenty-seven, I thought my life was a line you could draw with a straightedge. Career in a…

My mom slipped a gold necklace into my 15-year-old daughter’s bag and got her ARRESTED for shoplifti… CH2

Part One: The bench outside the juvenile intake room was too small for any grown-up to sit on without looking…

I Inherited a Stranger’s House by Mistake. The Real Heir Changed My Life Forever… CH2

Part I I was halfway up a ladder in the back of Murphy’s Hardware, stripping rotten trim from a second-story…

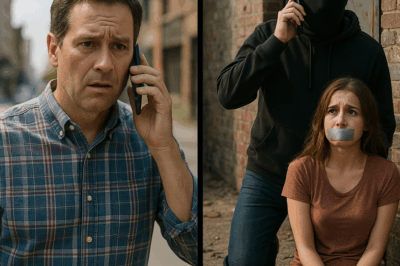

A trafficking ring took my daughter and told me to forget her, They didn’t know who I was… CH2

Part I The morning sun spilled into my kitchen as if it had someplace important to be. It turned the…

My Nephew Came Through a Snowstorm Carrying a Baby: “Please Help, This Baby’s Life Is in Danger!… CH2

Part One: The wind battered Harry Sullivan’s old farmhouse as though the storm had a grudge against him personally. Snow…

My Wife Thought I Was Asleep On The Couch. I Heard Her Sister Convinced My Wife To Get Pregnant… CH2

Part I If you’ve ever worked a code, you know there’s a rhythm to disaster. The chest compressions, the count,…

End of content

No more pages to load