Part I:

I wasn’t snooping. I swear I wasn’t. It was nearly two in the morning and the house had that heavy, humming quiet it gets when everyone is asleep except the one person losing her mind. Miles lay beside me breathing evenly, the kind of steady, confident breath you earn from decades of being the man who always gets to fall asleep first. The thermostat clicked. Somewhere in the neighborhood a train’s horn split the night like a question no one wanted to answer.

I turned toward the nightstand for water. That’s when his phone vibrated.

The screen lit up the room in a square of blue-white, a small explosion in the dark. I didn’t reach for it. I didn’t have to. The lock screen preview was right there—letters crisp, betrayal efficient.

My silky tiger, you are incredible. I miss you already. Thank you for the two unforgettable nights.

All the air left my body. Two nights. He’d been in Houston. A leadership summit. Lanyards and slide decks and too-expensive cocktails charged to a corporate card. I’d made pot roast and checked Myra’s homework and texted him a photo of our dog wearing the sweater Rowan bought on a dare. I’d said I love you, sleep well. He’d said Goodnight, beautiful. And in some hotel room, some carefully anonymous king suite with a view, he’d been something else’s silky tiger.

I got up on legs that had turned into someone else’s furniture and stumbled to the bathroom. Cold tile. Harsh light. The faucet’s blast of water like a slap I was too tired to dodge. In the fogged mirror, a woman blinked back at me, mouth a small, shocked O, hair tangled with the effort of being fine for twenty years. “Twenty years,” I whispered to her. The number didn’t sound like time. It sounded like sentence.

I don’t know how long I stood there. Long enough for the mirror to clear and then fog again. Long enough for a part of me—the part that had always believed in our exceptionalism—to crack the way old paint does when a house settles. I came back to bed and lay down beside him without touching him. He didn’t stir. The phone went dark again. So did the room. The crack in me stayed.

By morning, the sun was unnaturally cheerful, and our kitchen insisted on being ordinary. Miles wore his navy suit. He buttered toast. He read half the paper, skimmed the rest, and said, “You look pale,” with the casual concern of a man who thinks he has already loved you enough today.

“Didn’t sleep,” I said, setting his coffee in front of him, careful not to spill, careful not to scream.

“Bad dream?” He smiled like the answer didn’t matter.

“Strange dream,” I said. “In it, everything I believed in turned out to be a lie.”

He paused—just the hiccup of a breath—and then the smile again, the one that convinced department heads and HOA committees and the hostess at that steakhouse we go to on anniversaries. “Dreams are weird like that,” he said, reaching to kiss my cheek. “But we’re real, Celeste. You and me—we’re solid.”

His lips were warm. My chest was hollow. The plate in my hand felt like a discus I could hurl through our wedding photo. I didn’t.

Instead, when the door shut behind him with the same Saturday-afternoon ease it had for two decades, I put the plate in the sink and called the one person who knew every chapter of my life.

“Hey, Tamson,” I said. “Coffee? I really… I really need to talk.”

She didn’t ask what about. She’s never needed to. “Thirty minutes,” she said. “Our booth.”

The café smelled like cinnamon and a promise that if you sat with your hands around a warm cup long enough, everything would make a kind of sense. Tamson was already there, auburn hair in perfect curls, lipstick exactly the color of something expensive. The light loved her face the way it always had. She looked up and did a double take.

“You look awful,” she said, half a joke.

“Miles is cheating.” The words came out too loud and landed on the table between us like a dropped plate.

Her fingers tapped the cup. Tap tap. Tap. “What? What makes you say that?”

I slid my phone across the table—his screen captured and saved to mine before I could talk myself out of it. Her eyes flicked to the message. A flicker of—something—crossed her face. I’d have missed it on any other day.

“He’s someone’s tiger,” I said, the bitterness coming up like heat. “And I was the idiot who thought we were unshakable.”

“Celeste,” she said quickly, too quickly, “maybe it’s not what it looks like.”

“Don’t,” I snapped. “Don’t defend him. Don’t make it softer so I keep swallowing it.”

She looked down into her latte as if answers swam there. The barista called a name. The espresso machine hissed. A baby laughed somewhere behind us. Ordinary sounds. Extraordinary betrayal.

“I’m leaving,” I said, standing. The chair legs scraped the floor. “I’m taking the kids and going to my parents in Blue Ridge. Rowan’s back this weekend. Myra’s home Monday. I’ll pick them up and… I’m done.”

She nodded without looking at me. “Are you sure?” she asked, voice wrong somehow—too high, too careful.

“You think I should stay?” The question came out razor-thin.

“Of course I’m on your side,” she said. “I just don’t want you to do something you’ll regret.”

“No,” I said. “I regret staying this long.”

I left her in the booth, cup clutched like it could float her. She didn’t follow me. Tamson never follows. She waits.

I drove home with that sick, hot clarity you get in crisis. I’d already packed the basics—clothes, the important documents, Myra’s favorite pajamas with the stars she thinks protect her dreams—but I’d forgotten the dumbest thing: her school reading packet. It was in the front hall closet with the library books and the reusable bags and that umbrella that always leaks.

Fifteen minutes, I told myself. Maybe twenty. In and out.

The house felt different, like it had expelled me while I was at coffee and was now embarrassed to see me back. I kept my eyes off the stairwell photos—Paris, the beach house with the bad plumbing, Myra on the first day of kindergarten missing her two front teeth—and went straight to the closet. My fingers found canvas straps blindly.

The front door lock turned.

My heart tried to leave through my throat.

He wasn’t supposed to be home. Not yet. He was a creature of schedule. His day ran on rails. The clock had never betrayed me before.

The back door, I thought. The kitchen, the deck, the side yard. I could be gone in ten seconds.

Then I heard the voice. Not his. A woman’s voice. Warm. Familiar.

“Don’t be so nervous,” Miles said, laughing, the kind of laugh he used with clients and with me when I used to be the one he wanted to charm. “She has no idea.”

“I don’t know,” the woman said. “She seemed different this morning, like she knew something.”

There are sounds the body recognizes faster than the brain. The particular lilt to a friend’s voice. The way an S softens when you’ve whispered secrets back and forth since sophomore year. Tamson. The name crashed through me, then ricocheted, breaking everything it touched.

I pressed myself against the kitchen wall, stupidly trying to disappear into drywall. The room tilted and then found a new angle. Footsteps. Their footsteps. Voices moving down the hall. They laughed—easy, relieved. The laugh you do when the real work of pretending is finally over.

The stairs creaked. They always have. It’s one of the things I love about our house—the way it announces movement, the way it remembers how we used to carry each other up to bed when we were too in love to walk like normal people. The creak cut a new way now—meaner somehow, because sound can be cruel too.

I don’t remember deciding. I was up the stairs before fear had a chance to argue. One hand on the banister so I wouldn’t fold. One foot in front of the other because the body is good at routine even when the heart is learning a new language.

Our bedroom door was open a sliver. Warm light and warm voices slid through the gap. I could have turned around. I could have made another life. Instead, I pushed the door open and flipped the switch out of habit or defiance—hard to tell which.

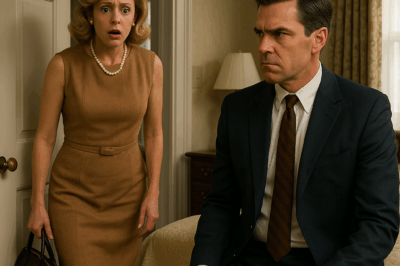

The room snapped into clarity. Miles stood in the middle of it with his shirt half-unbuttoned like he’d been in a hurry to forget me. His hair was a mess. Tamson stood near the bed—the bed—with her hair falling out of its perfect curls, lipstick smudged. For a second, none of us breathed. Then everything tried to happen at once.

“It’s not what it looks like,” Miles said, too fast. It’s what men say in movies when they’ve done exactly what it looks like.

“Really?” My voice was calm—an old friend showing up in a new dress. “Because it looks a hell of a lot like my husband and my best friend were about to screw each other in my bed.”

Tamson’s mouth opened. Closed. She looked at me like she’d just realized ghosts can be alive and angry.

“Celeste,” Miles began.

“Don’t,” I said. The word was a wall.

He took a step. I held up a hand. “Don’t come closer. Don’t touch me. I don’t want your explanations.” I swallowed. The taste of metal. “I don’t care.”

Silence. Not peace. The absence before a storm.

“You know,” I heard myself say, and wondered who was doing the speaking, “you could have picked any bed in the city. But you chose this one. God, the symbolism is almost… thoughtful.”

Something in his face—wounded. The audacity. I almost laughed. I didn’t.

“I packed,” I said. “The kids are coming with me. You can have each other. Enjoy your little jungle. My silky tiger. My tigress.” I made my voice dainty. His face flinched like the words had teeth.

“Celeste,” Tamson tried, voice small.

“You don’t get to say my name,” I said without looking at her. “You forfeited that.”

I picked up the suitcase, the one I’d left at the top of the stairs that morning when I thought coffee and a friend would help. The wheel thumped every other stair. The sound was a drumbeat. A pulse. A countdown.

Miles followed me down the hall, saying my name the way you say it when you think it will do something it won’t. I opened the front door. The night was cool and ordinary. Porch light insects performed their stupid ballet.

“Please,” he said on the threshold. “This isn’t what you think.”

“It’s exactly what I think,” I said, and meant it. He reached for my arm. I stepped back. He said, “I love you,” like a last line in a play.

“Too bad you forgot to tell your tigress,” I said, and walked into the dark.

The first twenty miles of the highway were a blur of asphalt and the kind of breathing you do when your body is getting rid of something poisonous. The dashboard chimed: Low fuel. Of course. I took the next exit on instinct and wound up at a gas station with buzzing lights and a gravel crunch that felt like teeth. Two pumps. A dinged metal door with a chime that tried and failed to be cheerful.

I got out and shoved the card into the slot and pressed 87 because it was easiest. The nozzle thunked into the tank. I stared at the numbers ticking up and thought about twenty years and wondered what number that would be if you could put it on a pump.

“Rough night?” a voice said behind me. I didn’t jump. I think I was out of jumps.

“Why would you say that?” I managed, eyes on the numbers.

“Most people don’t cry while filling up,” he said. The voice was low and steady and had that quality some men have when life has knocked them around enough that they’ve stopped trying to be anything but human.

I touched my cheek, surprised to find it wet. I hadn’t felt the tears arrive. “Sorry,” I said automatically.

“No need,” he said. “Coffee on the house? I make a mean midnight drip.”

I should have said no. Should have gotten back in the car and driven to Blue Ridge on adrenaline and stubbornness. But the tiny table in the window with two mismatched chairs looked like a life raft. “Okay,” I said.

Inside, it was warmer than the lights suggested. A heater hummed. Someone had tried for décor—maps pinned in a collage, postcards from places people meant to go, potted plants valiantly alive. The man behind the counter had a graying beard and the kind of eyes that didn’t force themselves on you. He held out a paper cup.

“I’m Jude,” he said. “Owner, cashier, therapist if you’re desperate.”

“Celeste,” I said.

We sat. The coffee steamed. He didn’t pepper me with questions. He just sat across from me and let the table be between us like a good fence. When I started talking, I didn’t mean to say as much as I did. Then I did anyway. “He was in Houston,” I said. “A summit. Two nights.” I laughed, a small awful sound. “Two nights. Isn’t that neat? Doesn’t that fit so tidily into a calendar block?”

Jude nodded. “Sometimes the worst things are the ones that respect your schedule.”

“He used to say I grounded him. He used to—” I stopped. “She’s my best friend.”

“That’s a special kind of knife,” he said quietly. “The ones closest to your ribs.”

“You don’t seem surprised.”

“I’m not,” he said, and told me about a wife who died and the way grief had taught him which people were made of paper and which were made of cloth. “This place helps,” he said, gesturing at the shelves of beef jerky and wiper fluid. “It’s simple. People need gas. Sometimes they need to talk. Sometimes they need both.”

“You have kids?” he asked after a while, gentle without being nosy.

“Two,” I said. “Rowan’s in college. Myra’s thirteen. They’re everything.”

He smiled. “Then you’ve already got a start.”

We didn’t flirt. There was no spark, no rom-com swell in the room. There was just the soft, central relief of being witnessed without being managed. When the coffee was gone, he wrote his number on a small receipt and slid it across. “In case you need more caffeine and less judgment,” he said with a half-salute.

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it for more than the coffee.

Blue Ridge looked the way it always does—craning pines, a porch that creaked in welcome. My mother answered the door in a nightgown, hair pinned like a crucifixion. She took one look at my face and didn’t ask a single question. “Guest room,” she said. “Sheets are clean. I’ll make tea.”

Rowan drove in before dawn—my boy who will always be taller than me but still leans down when I hug him like he’s protecting something important at the base of my neck. Myra tucked under her childhood quilt as if the stars printed there could do the night’s job better than I could. I slept for four hours and woke up as tired as when I’d closed my eyes.

At breakfast, my mother made blueberry pancakes like you make offerings to a god you don’t really believe in anymore. My father sat at the head of the table burying himself in the sports section, pretending to be a man who had never once told my mother that suffering was a talent.

When the plates were cleared and the house had redistributed itself—Rowan in the garage with my father, Myra in the yard with a notebook—my mother said, too casually, “I invited Miles.”

I looked at her. “You did what?”

“He’s your husband,” she said, busy with a napkin the way women get busy when they’re about to apply a standard that has killed them. “You two need to talk.”

“No,” I said. “We don’t. Not here.”

“All men stray now and then,” she said, like she was comforting me. “It doesn’t mean you burn the house down.”

“It wasn’t a stumble,” I said. “He slept with my best friend.”

“It’s still your marriage.”

“And that’s supposed to mean what?” I asked. “That I swallow hard and pretend I don’t have taste buds?”

“That you fight,” she said.

“I’ve been fighting for twenty years,” I said, not loudly, not cruelly, just with the kind of quiet that ends things. “I’m not going another round.”

She didn’t argue. She sighed. The sigh of a woman disappointed by a daughter who refuses to become her.

That afternoon, Myra sat beside me in the garden and drew tulips that didn’t exist—a field of them, heads turned toward something bright. “Is Daddy coming back?” she asked without looking up.

“Not in the way you’re used to,” I said.

She nodded once and colored the corners with gold.

That night, when the house slept again, I printed the forms. No more ceremonies. No more counseling sessions where I swallowed rage to be the kind of wife who tries. Divorce looks clinical on paper. Names. Dates. Assets tombstoned into lines. I filled the blanks like I was taking a test I was finally prepared for.

I texted Rowan: Pick you up Friday. I texted Myra’s teacher: She’ll be out Monday. I texted Jude the gas-station philosopher without expecting an answer: Thanks for the coffee. I made it to Blue Ridge. He wrote back: Good. The coffee here has loyalty issues anyway.

I slept then, the kind of sleep that comes when you’ve decided on a direction. The night had fewer edges. The house creaked like a body stretching.

In the morning, the town held itself the way only small towns do—like it’s both bored and ready to judge. I let it. By then I’d learned what other people’s narratives are worth. I poured coffee into my mother’s oldest mug, the one with the chipped handle and the faded cardinal, and thought: tomorrow the lawyer. The day after, Rowan. Then Myra. Then Greenville, the townhouse with the ridiculous rent and the light that falls just right in the late afternoon. Then a new grocery store aisle. Then a bed that remembers only me.

Later, I took a walk because sometimes staying still feels like agreeing. I walked the loop we’ve walked since I had braces and bangs—the one past the pond and the Miller’s mailbox with the metal flag that squeals. The air smelled like pine and the last of winter’s resolve. My phone buzzed. A number I knew too well. I didn’t answer.

I came back to the house with my hair frizzy and my lungs scrubbed. My mother looked up from a casserole she was assembling like a lifeboat and said, “He’s on his way.” I nodded. I wasn’t going to stay for the talk. I wasn’t even going to stage a scene. I was going to leave the house the moment I saw his car and go sit at the diner down the street pretending to read a menu until the waitress released me with pie.

But that was tomorrow’s problem. Tonight, the list in my head was small: feed Myra; call the school; find the birth certificates; sleep in a bed that once held a girl who thought the worst thing that could happen to you at night was a thunderstorm.

I went upstairs, closed the guest room door, and exhaled so long my ribs complained. Somewhere, a train sounded lonely and brave and inevitable. I wanted to be that.

It would take months. Lawyers. Court. Boxes. An emptying and a filling. People would say clumsy things about forgiveness and failures of character like they’d discovered nuance. Some would stop calling altogether, which is its own kind of mercy. Others would arrive with casseroles and advice and questions that looked like care but tasted like curiosity. The kids would cry and then stop crying and then start again. We’d watch movies under blankets. We’d eat cereal for dinner. We’d survive.

But first, there was the call to make in the morning. The one where you give your entire history to a receptionist who types like a woodpecker and says, “We have a slot Thursday at 10,” and you say, “I’ll take it.” The one where you stop being a story told in pictures on a wall and start being a file folder.

I set an alarm. I turned off the light. I lay down.

And for the first time in twenty years, I didn’t fall asleep listening to the way he breathed. I fell asleep listening to my own.

Part II:

The next weeks blurred into the kind of time you don’t scrapbook. Lawyers’ offices with stale coffee and gray carpeting. My mother’s sighs thick as gravy. Myra’s questions that landed like stones in my stomach: “Does Daddy still love me?” Rowan’s jaw tightening every time his phone buzzed, because even at nineteen he already knew how to protect me by pretending not to be angry.

Miles tried everything—calls, texts, emails with subject lines like Please Just Listen. I didn’t answer. He sent flowers once, delivered to my parents’ porch like I might mistake their perfume for atonement. I left them outside until they wilted.

At night, I would step onto the porch alone, the mountains shadowed against the sky, and read Jude’s one-line texts. Nothing dramatic—just tiny check-ins. “How’s the air up there?” or “I burned the midnight coffee again. Tragic.” Little reminders that not everyone wanted something from me.

Savannah was gray the morning of the hearing, a damp, heavy kind of gray that made even the courthouse look tired. I wore a navy suit I hadn’t touched in years and shoes that pinched. Miles was already there when I walked in, seated beside his attorney. He looked hollowed out, not polished, not smug—just tired.

The lawyers shuffled papers, the judge recited procedure, and we sat across from each other like two colleagues dividing office supplies. The words didn’t sound like our life—they sounded like a spreadsheet. “Assets… custody… residence.”

Then, out of nowhere, Miles stood. “I’d like to make a statement.” His attorney looked startled.

The judge raised an eyebrow. “Mr. Harrington?”

He cleared his throat. “I waive my right to any shared property. Everything goes to Celeste and the kids. The house, the accounts, the car. All of it.”

Gasps whispered through the courtroom. My own attorney leaned toward me, whispering, “He can’t be serious.”

But he was. His voice didn’t waver.

The judge frowned. “You understand what you’re saying, Mr. Harrington?”

“I do.”

I stared at him, not with gratitude—never that—but with confusion. What was this? Guilt? A power play? Or just a man finally admitting he’d already lost the only things worth keeping?

Then I saw her. Tamson. Slipped in through the back, sitting alone. Her coat wrapped tight, her face pale, her eyes hollowed. She looked like she hadn’t slept in weeks. Miles never glanced her way. Not once. Something between them had already broken, and I didn’t need the details to know it was final.

When the gavel struck, it was over. Twenty years gone in the crack of wood on wood.

I walked past him without speaking. He didn’t reach for me. He just sat down, shoulders slumped, as if even his own body was tired of carrying him.

Outside, the air bit sharp. I didn’t cry. I didn’t look back. I just kept walking.

The townhouse smelled of fresh paint and cardboard. Most of the boxes were still sealed, the walls bare, but the air—it was mine. Rowan carried a box marked KITCHEN and set it down with a grunt.

“Where do you want this?” he asked.

“Anywhere but the stairs,” I said, managing a tired smile.

Myra came skipping behind him, holding up a painting she’d made. Bold swirls of red and gold melting into blue. Chaotic, hopeful. “For the living room,” she said proudly.

I looked at it, really looked, and felt something stir. “Perfect,” I said.

That night, when the kids were asleep, I opened one of the last boxes from the old house. At the bottom, beneath receipts and old notebooks, I found a bundle of letters tied with a faded ribbon. Tamson’s handwriting. My chest tightened.

The letters were to Miles. Postmarked a year before I met him.

“I miss you. Why won’t you write back? I wait every day for the mail.”

Another: “You promised you’d wait for me. What changed?”

Another still: “I guess I have my answer. You’re gone, but I won’t forget.”

The last envelope held a photo. Tamson and Miles, barely more than kids, leaning against a fence, smiling in love.

I sat on the floor, letters spread around me like wreckage. They’d known each other long before me. And yet—neither of them had said a word in all these years.

The next morning, I drove to Miles’s mother’s house. Lemon polish, floral wallpaper—nothing had changed. She opened the door with her usual guarded expression.

“Celeste,” she said, surprised. “Come in.”

I held out the letters. “Did you know about them?”

Her face drained. She sat heavily in a chair, reading the words. Her hands trembled. “He wrote to her,” she whispered. “Every week after we moved. We checked the mailbox together. He never heard back.”

“That’s not true,” I said. “She wrote. Dozens of letters. I found them.”

She shook her head, confused. Then slowly, the realization dawned. “My mother lived with us then,” she whispered. “She… she intercepted them. She didn’t think Tamson was good enough for Miles. She told me once she wanted him to ‘marry up.’”

The room tilted. Twenty years of silence. Twenty years of misunderstandings, all because an old woman decided she knew better than fate.

That night, I sat in my backyard, phone in hand, staring at Miles’s name. Against every instinct, I called.

He answered on the second ring. “Celeste?”

“I found the letters,” I said. “All of them. She wrote to you. You wrote to her. You never got each other’s words.”

Silence. Then a breath like a man finally confirming what he always suspected. “So it was real,” he murmured.

“Yes,” I said softly.

He didn’t apologize. He didn’t ask for anything. He just said, “Thank you for telling me.” Then the line went dead.

I sat there under the stars, the ache in my chest sharper than anger. Maybe I had been the rebound once. But we had built a family. And real or not, it hadn’t lasted.

A week later, I drove past the mountains to clear my head. Without planning, I ended up at Jude’s gas station. The pumps still flickered under bad lighting. The little café table was now surrounded by potted plants and travel mugs.

He looked up from behind the counter, eyes lighting when he saw me. “You again,” he said. “You never did finish your story.”

I smiled. “That’s because I’m still writing it.”

We sat together, no past chasing us, no future demanding promises. Just two people in the middle of the night, sipping coffee, letting silence be safe.

For the first time in months, I wasn’t waiting for betrayal. I wasn’t bracing for lies. I was just here. Alive. Forged by fire, and finally free to start again.

Part III:

The townhouse had the kind of quiet you only get in a place that hasn’t learned your sounds yet. Even the refrigerator seemed to hum politely. I was reading a lease addendum I didn’t fully understand and pretending that made me a person with control when someone knocked.

It wasn’t a neighbor’s “welcome to the building” rap. It wasn’t Rowan’s impatient cadence or Myra’s three-tap code. It was two knuckles, soft, a wait, then one more—like someone hoping the door might open itself if they were gentle enough.

I knew before I looked.

Tamson stood on my stoop without eyeliner, without earrings, without the ring she used to twist when she lied. She looked smaller. Not thinner—lighter, somehow. Like regret had scoured her to the essentials.

“I need to talk,” she said, voice so tired it almost wasn’t a voice.

“I don’t,” I said, and meant it, until I didn’t. Something in the way she held herself—careful, like if she moved too fast she’d shatter—pulled the better part of me forward.

I stepped aside. “Ten minutes,” I said. “No history lessons.”

We sat at the small kitchen table, the one Rowan had assembled backward and then fixed, the one Myra had christened with glitter glue I would never fully erase. I didn’t offer coffee. I didn’t offer comfort. The table could be Switzerland; I didn’t have to.

“I loved him,” she said, hands flat, eyes on the wood grain. “Before you. Before any of this. He was my first—” She stopped herself, and I was grateful. “He moved away and then… silence. I told myself I was dramatic, that I’d built a cathedral to a boy. I told myself I’d outgrow it.”

“You didn’t,” I said.

“I tried,” she said. “And then I met you. And you were… you. We became friends. Real friends.” She swallowed. “I told myself the past didn’t matter. It did. I tucked it under everything. I tucked it under you.”

“You still slept with my husband,” I said, each word its own decision.

“It wasn’t a long… it wasn’t—”

“Don’t call it an affair,” I said. “Don’t make it sound like a program.”

She flinched. “It happened three months ago. His company party. We drank too much. It was stupid and reckless and—” She stopped again, jaw tight. “It didn’t go on for years. We didn’t build a second life. I’m not saying that to make it better. I’m saying it because it makes it worse. There wasn’t momentum. There was a choice.”

The room seemed to lean toward us. Outside, a horn blared and then apologized.

“I found your letters,” I said. “From before. And the photo. His mother says he wrote too. Her mother—” I let the rest land where it would.

Tamson’s eyes widened, then went glassy. “She… intercepted them?” she asked, like a person learning a word that explains an ache.

“Looks that way,” I said.

She laughed a sound that had nothing to do with humor. “We spent twenty years grieving a thing that might have been, and then when life tested the fantasy, we failed a very real woman.”

We let that sit. Truth is heavy; you don’t pass it back and forth quickly unless you want to break something.

“Did you think he would leave me?” I asked. I didn’t coat it. The question was as raw as my throat.

She closed her eyes. “I didn’t plan anything,” she said. “After—you left and he came to me. He said he didn’t know what he wanted. He said he’d loved me once and he didn’t know if that meant anything anymore.” She opened her eyes. “It felt like a lightning strike. Like the universe had finally taken pity on a younger version of me. But when we were together… it didn’t feel like home. It felt like I was trying to inhabit an old diary entry.”

“You both are different now,” I said. “He is. You are. I am.”

She nodded. “I kept thinking the rightness would click into place like a seatbelt. It didn’t. It clicked for you. For years. I told myself I was over it. Then I wasn’t. Then I confused a tremor for an earthquake.” She took a breath that seemed to cost her something. “I’m moving to Seattle. Job offer. I need a city where my past doesn’t grocery shop with me.”

“Good,” I said, because sometimes the kindest thing you can give someone is no permission at all.

“I don’t expect forgiveness,” she said, standing too quickly, catching herself on the back of the chair. “I just couldn’t leave without being the one to say what I did out loud.”

“You lied to me,” I said. “For months, and probably in little ways for years. You wrapped care around it like a bow. That made it uglier, not prettier.”

She nodded, eyes shining. “I know.”

“And I believed you,” I said. “Because that’s what I do. That’s what I did. I believed people who said my safety was their priority.”

“I hope you still do,” she said. “Just not… just not me.”

That almost undid me. Almost. It didn’t.

At the door, she hesitated. “One more thing,” she said. “You were never a consolation prize. I was jealous of you because you were chosen—by him, by the life you made, by the kids who look at you like you invented air. I wanted what you had because you had it. I think a part of me thought breaking it would make me feel powerful. It made me feel small.”

“Goodbye, Tamson,” I said.

She left. She did not turn back. I shut the door and slid the chain—an old ritual that suddenly felt like more than hardware.

I stood in the kitchen until the clock on the microwave clicked into the next minute. Then I called my mother.

She arrived with grocery bags and theory. She always has both. She set down eggs, butter, a bunch of parsley, then the words: “I told you to talk to him. I told you to try.”

“I did talk,” I said. “He listened. He didn’t ask to come back.”

She leaned against the counter and rubbed her hands together like she could summon warmth by friction. “When your father was your age,” she began, and I held up a hand.

“I don’t want your endurance as a template,” I said. “I know what it cost you. You don’t get points for surviving a house you had to disappear in.”

She deflated, then surprised me. “You’re right,” she said. “I thought staying was my job. I thought leaving was a moral failure. I stayed so long I started mistaking my outline for furniture.” She reached out, awkward, and tucked a strand of hair behind my ear like I’d suddenly been promoted back to her daughter. “You broke something on purpose because it was suffocating you,” she said. “I don’t know how to teach that. I only know how to applaud it.”

A sound escaped me—half laugh, half sob. “Applause is loud,” I said. “I like quiet.”

“Then I’ll chop parsley,” she said, and did.

Rowan came home from his shift at the campus coffee shop and collapsed on the couch in a posture only the young can survive. Myra painted on her bedroom wall a wash of blues and golds she called Mom’s Sky. She invited me to add a star. I did—a small, messy one in a corner, where I’ve always lived best.

Later, when the house exhaled into evening, I texted Jude: Hypothetical: a person whom life has stomped on brings pasta ingredients to your door and insists on chopping. Is this a red flag?

He wrote back: Only if they salt the water like a coward. Then: Tell me you have real Parmesan.

We have dignity in this house, I typed.

Saturday, he answered. I’ll bring the wine. You bring your “I’ve got this” face.

It’s dented, I wrote.

Those hold better, he said.

Two days later, the doorbell rang again. I braced for a neighbor, for a delivery, for the building’s super. It was Miles.

He stood on the step without a tie. Without the smell of the cologne that used to announce him three seconds before the door did. He looked older in the way sorrow does to a face. He held an envelope I recognized—the manila kind lawyers love.

“I’m not here to fix anything,” he said before I could weaponize the hinge. “I just came to say something I wish I’d said when it mattered.”

“You said a lot when it mattered,” I said. “Most of it into someone else’s pillow.”

He took it, didn’t flinch. “I’m sorry,” he said, plain. “Not just for what I did, but for how long I let you be alone in our marriage.” His eyes were wet. He didn’t reach for me. Points for not doing the things that would make me angrier. “You were never my second choice,” he said. “That sounds like nothing from me. I know. But it’s true.”

I let the words pass through me like wind through those paper decorations you hang because a party needs something to catch light. “I found the letters,” I said. “You two were dismantled by a person you trusted before either of you learned the word consent.”

He blinked. “I kept thinking I’d imagined it,” he said. “The… us of then.”

“It was real,” I said. “It’s just not current.”

He nodded. “You’re doing well,” he said, taking in the boxes, the mural, the parsley stems on the cutting board. “This looks like… life.”

“It is,” I said.

He handed me the envelope. “Quit-claim deed. Signed.” He lifted a shoulder. “I meant it in court. I don’t get to keep the house I defiled from you. Or the money we built on your steadiness.”

Some men are never more seductive than when they are finally decent. I stepped back anyway. “Thank you,” I said, because that’s what you say when someone does the thing they should have done without applause.

He nodded, looked down, then up. “Take care of them,” he said, meaning the kids, meaning me, maybe meaning himself in some roundabout way. He tried for a smile that didn’t pretend. “You always did.”

After he left, I sat on the floor in the half-unpacked living room and let the quiet sit on my shoulders like a shawl. Closure isn’t a single door slamming. It’s a series of clicks at the ends of long hallways. You don’t even know you were cold until the draft stops.

Saturday came in soft, and Jude arrived with a bottle of red and a grocery bag he refused to let me rummage in. He moved in my kitchen like it had been designed for him, which was less romantic than it sounds and more practical. He stirred, tasted, salted like a man who has survived worse than blandness. When the water hit a proper boil, he saluted the pot the way some people bless themselves.

We ate on the back step because the table was covered in Myra’s art supplies and because a step feels like a thing you sit on when you’re about to become someone else. The wine warmed my chest. The sky held on to color longer than it had any right to.

“You ever think about what you’d say to the you from a year ago?” Jude asked, not as a prompt but as a curiosity.

“I’d tell her the house will be emptier,” I said, “but her heart won’t. I’d tell her that grief isn’t proof you chose wrong. It’s proof you chose deeply. And I’d tell her to check the gas tank before pulling a dramatic exit.”

He grinned. “I’d tell me not to buy wholesale biscotti,” he said. “It makes you a person strangers confess to.”

We didn’t kiss. Not because we were afraid but because this deserved a pace that would withstand weather. He left with the dishes stacked and the promise of a second Saturday that didn’t need capital letters to be real.

In the weeks that followed, life became less about what had been taken and more about what we were building with what remained. Myra’s mural spread to the corner she’d left bare, a decision I’d thought was restraint and turned out to be composition. Rowan brought home a girl named Cat who watched him like he was a possibility and not a project. My mother joined a volunteer group and stopped sighing like it was her side hustle. My father started writing bad poetry and reading it to her on the porch, and I let them be ridiculous because ridiculous is better than resigned.

One afternoon, out of nowhere, I stopped in at the gas station on my way back from a client meeting. The same fluorescent lights buzzed with the confidence of a failing bee. The door chime still tried to be upbeat. The little table now had two plants trying their best.

“You never did finish the story,” Jude said, sliding me a coffee I hadn’t ordered.

“I don’t think it finishes,” I said. “I think it… lands. And then it takes off again.”

“Like a train,” he said.

“Like a person,” I said.

We sat in companionable silence watching a storm decide whether to commit. The door opened. A teenager bought gum and swagger and left. A woman came in to ask for directions to a road I pretend to know until Google rescues me. The ordinary heroism of commerce did its thing all around us.

My phone buzzed. A text from Miles: Rowan’s game tomorrow? Can I come? I typed Yes and added the time. He replied with a thumbs-up and no additional sins. Progress, measured in emoji.

I put the phone away and looked at Jude. He raised his cup. “To bad lighting,” he said.

“To better choices,” I answered.

Night fell the way it always does—honest, inevitable, not interested in my metaphors. I drove home with the window cracked, the air smelling like rain and something that felt suspiciously like peace.

On the fridge, beneath a magnet shaped like a cardinal, Myra had taped a new note in her careful not-quite-cursive: Mom’s Fresh Start: Ongoing. She’d drawn a box next to it and left it unchecked on purpose.

I checked it, then drew another box. Some things deserve to be marked done. Others deserve to be lived.

Part IV:

Saturday began the way good days often do—quietly, like it didn’t want to jinx itself.

The townhouse felt less like a rental and more like a place we’d persuaded into being ours. Cardboard had thinned to a single stack in the hall. Myra’s mural dried into a soft sheen that caught afternoon sun and threw it gently back. Rowan had already left for warmups, hair damp, socks mismatched on purpose because he insists on courting chaos in small, controllable ways.

I brewed coffee and watched steam ghost up. My phone buzzed with a text from Miles.

I’m at the field. Far side bleachers. I brought water for the team if that’s ok.

It’s okay, I typed. We’ll be on the third-base side.

No apologies. No overreach. A logistics exchange, clean and unsticky, like handing a baton. The way I wish we’d done more things when we were too busy proving we could do everything.

“Can I paint stars on my shoes?” Myra asked, padding into the kitchen in an oversize sweatshirt, hair in a lopsided bun she insists is an aesthetic and not an accident.

“Only if they don’t come off on the car mats,” I said.

She grinned and made two quick constellations on the white rubber like she’d been planning it all week. “They’re for speed,” she said, blinking with mock-seriousness.

“Obviously,” I said, and handed her the glitter pen like a microphone.

We drove with the windows cracked even though the air still had bite. The ballfield unfolded below the hill in diamonds, chain-link fences casting long shadows like crosshatch shading on a drawing. A chorus of metal bats and coach whistles and the strange civic hymn of parents hollering politely filled the air.

Rowan spotted us and lifted his chin in that barely-there hello men use when affection is inconvenient. “Good luck,” I mouthed. He rolled his shoulders, stepped into the box, and didn’t look back.

Miles sat where he said he’d be, a row down, a few seats over, a man inside the boundaries we’d drawn. He held a cardboard flat of water bottles like an offering he wasn’t going to force on an altar. When he turned and saw us, he didn’t stand, didn’t wave big, didn’t try to make the moment perform for onlookers. He nodded. I nodded back. Co-parents. That word used to taste like surrender. Today it tasted like a plan.

The first inning was messy in the way opening acts tend to be. Rowan fouled one so hard it reminded the sky of him. On his third at-bat, he connected—a clean, satisfying crack—and sent the ball on a low arc between center and right. He rounded first with that long stride I still can’t believe came from the toddler who once tripped on air, and when he slid into second, safe, hands up, eyes bright, something in me stood up too, on the inside, and clapped until my palms stung.

Myra yelled, “LET’S GO RO!” with all the ferocity her small frame could gather, then leaned into me. “He’s so cool when he’s not being dumb.”

“Universal brother paradox,” I whispered.

Between innings, Miles walked up the aisle to where we sat. He looked at Myra first. “Stars for speed?” he asked, deadpan.

She tried not to smile. Failed. “They worked.”

He crouched so his face was level with hers. “You okay?” he asked, simple. She shrugged, the shrug that covers a lot—school, sleep, secrets, sudden weather. “Yeah,” she said. “I’m painting my wall.”

He glanced at me, question there—permission to ask? I nodded once.

“What’s on it?” he asked.

“Mom’s sky,” she said. “And a corner for you.”

He swallowed in that way you pretend is about saliva. “Thank you,” he said, and then he stood, and then he went back to the waters and the boys who didn’t know and didn’t need to.

We won by a run that didn’t matter. Some games are about score. This one wasn’t. In the parking lot, under a sky that was holding its breath before deciding whether to storm, Rowan slung his bag into the trunk and said, “Cat’s family is grilling tonight. Can I?”

“Text me their address,” I said. “Midnight curfew.”

“Eleven-thirty,” Miles said automatically.

Rowan laughed. “Compromise: eleven forty-five.”

“Sold,” I said, and the three of us smiled, and nothing hurt.

As we drove away, my phone hummed with another text—Tamson.

Flight out at 4:10. If you’d ever… if you’d let me, I’d like to say goodbye in person. Gate A7.

I stared at it until the light at the corner turned green again. Myra saw my face in the rearview. “It’s her,” she said. “You can go, if you need.”

“I don’t need,” I said. Then, after the next intersection, “But I think I might want to.”

She nodded like a person who has already learned that wanting and needing are siblings who rarely agree.

Greenville’s airport is small enough to feel like a promise kept and big enough to feel like you might be going somewhere. I parked in short-term and walked in with my hands empty on purpose—no bags, no distractions, just the steady metronome of decisions.

Tamson stood by the window at Gate A7, watching a plane taxi slow as a prayer. She wore jeans and a gray sweater like she was trying to be a neutral. She’d pulled her hair back into something practical. The woman who turned to face me wasn’t the girl from the photo. She wasn’t the woman in carefully curated brunch selfies. She wasn’t even the person who’d stood in my bedroom pretending to be tongue-tied by fate. She was somebody rawer. Somebody undone enough to be honest.

“You came,” she said. Gratitude, not surprise.

“You asked,” I said.

We stood shoulder to shoulder for a moment. Out on the tarmac, a luggage cart beeped with the single-minded joy of a creature with one job. A kid in a dinosaur backpack pressed his palms to the glass and declared, “Big airplane!” to anyone who might be foolish enough to disagree.

“I’m not here to re-litigate,” I said. “I’m here to end.”

“Me too,” she said.

A family walked past trailing snacks and arguments. The overhead announced a boarding change for a different gate. A pilot laughed in that quiet way pilots laugh, like they’re sharing a joke with altitude.

“I spent twenty years writing the same story,” she said without looking at me. “I kept revising the ending, but the first chapter never changed. I thought I was… loyal. Noble, even. Turns out I was just stubborn about a narrative that couldn’t bear weight.”

She exhaled. “You were the only person I never wrote into it. That’s on me.”

“You were in my first chapters too,” I said. “The friend every good scene needs. Not a foil, not a plot device. A character with agency. And then, at the worst possible time, you decided to be a twist.”

“I hate that that’s true,” she whispered.

“I hate that I didn’t see it,” I said. “But I don’t hate you. Hating takes energy I want back.”

She blinked hard. “Seattle will be good for me,” she said. “Rain that doesn’t belong to our memories. Coffee that tastes like beginning.”

“Don’t steal Jude’s brand,” I said, and she laughed, surprised tears making tracks she didn’t wipe.

“You deserve a friend who never measures your life against her ghost,” she said.

“I have some,” I said. “I’m learning to be one for myself.”

The boarding call crackled. Group A.

She looked at me like she was memorizing a face she’d once painted and then sanded down. “I loved you,” she said. “That part wasn’t a strategy. I loved you badly in the end, but I did.”

“I know,” I said. “I loved you too. Goodbye, Tamson.”

She nodded once, like a person signing a document they finally understand, and walked toward the line with the lightest carry-on I have ever seen her hold. I watched her hand the agent her ticket. I watched her walk down the jetway. I realized that the knot in my sternum wasn’t anger anymore. It was a stitch that had done its work and could be removed.

On the way home, the clouds parted and produced a wedge of blue so clear it looked manufactured. I rolled down the window. The air smelled like wet asphalt and pine. The radio served up a song I liked in college and had pretended I didn’t because Miles called it “too on the nose.” I sang along, off-key, and didn’t apologize to the car or the universe.

That night, the townhouse filled with the noise of a family practicing new habits. Rowan came home late and deposited his long body across the couch, talking about Cat’s father’s unreasonable devotion to smoked meats. Myra announced that glitter had escaped containment and that we should prepare emotionally. I slid a pizza into the oven like a note under a neighbor’s door. Miles texted a photo of a box labeled BASEMENT—TOOLS that he’d dropped at the storage unit I’d rented. Where do you want this eventually? he asked. Shelf three, I typed, without flourish. Left side. Label outward.

Small systems. The scaffolding for bigger structures.

We ate on the living room floor because the table was still a war zone. Rowan stole Myra’s crusts; she pretended to be outraged; he pretended to be chased; laughter did that thing it does when it remembers how to multiply. When they wandered to their rooms—Rowan to homework he swears is optional, Myra to a mural she insists is collaborative—I carried two plates to the sink and looked out the window. The porch light put a halo on the railing. Somewhere across the parking lot, someone practiced a trumpet with heroic determination and questionable embouchure.

My phone buzzed, and the name on the screen made my heart do a new, cautious thing. Jude.

View worth a detour?

Always, I typed. But only if you bring the wine you promised.

Already at your door, he wrote.

I opened it to find him holding a bottle in one hand and a grocery bag in the other. “The pasta emergency hotline received a call,” he said. “Figured I’d follow up.”

“You are the hotline,” I said.

We cooked without choreography because we’d already learned each other’s steps. He stirred. I salted. He sighed with theatrical despair at my knife skills and then admitted my garlic ratio was morally superior. We ate again on the back step because until the table is cleared, we are step people. The night was cool enough to require the shared blanket Myra had left in a heap. We ignored it and then didn’t.

“I saw her,” I said after a while, the words moving into the air like we’d been saving them a path. “At the airport.”

He waited, the way he does.

“It was… small,” I said. “Not cinematic. No speeches that cured anything. Just two people telling the truth at last, gently and in daylight.”

“Those are the expensive kinds,” he said. “The ones that don’t give change.”

“She said she loved me badly,” I said.

“And you?” he asked.

“I loved her,” I said. “I don’t anymore. Not like that. Not in any way that requires me to bargain with myself.”

He nodded, took a sip of wine, set it down. “You know what I like about you?” he asked.

“My tragic gas station origin story?” I said.

“That,” he said, smiling. “And the way you choose slow when everything tries to make you sprint.”

I looked at his hands, the half-crescent scars, the nick near the knuckle that his wedding ring used to hide. I looked at the way he waited, and I thought of all the waiting I’d done for the wrong things and all the pauses I’d filled because silence had once meant danger.

“Can I tell you what I don’t like?” I asked.

He raised an eyebrow. “This is a bold pivot.”

“I don’t like biscotti,” I said.

He put a hand to his heart. “We were on such a roll.”

I laughed, and it didn’t sound foreign anymore.

We didn’t kiss then either. I wanted to. He wanted to. But he didn’t move first, and neither did I, and that restraint felt less like fear and more like holding a note a second longer than the sheet music dictates because you know you can.

When he left, he took the trash bag with him because he’s the kind of person who understands acts of love come in sizes you can’t post. I stood in the doorway with the porch light on and watched him cross the lot, and then I turned off the light and stood in the dark, and neither state scared me.

Two weeks later, I found myself back at the gas station at dusk because ritual matters. The place had acquired three more potted plants and a hand-lettered sign that read We Sell Hope (and Wiper Fluid). Jude was arguing with the receipt printer, which had chosen to go on strike for better conditions.

“You ever notice,” he said without greeting, “how machines revolt only when you have a line?”

A man behind me sighed with empathy born of paper jams. “Every day,” he said.

I bought gum I didn’t need and a map I absolutely didn’t need, just to watch him ring them up and slide them across the counter like a benediction. We sat for five minutes at the little table and watched the highway take people away to places they thought were better. The sky went lavender, then something deeper. I told him I had a client who wanted open shelving because that’s what the internet told her was happiness, and he told me he had a customer who swore the right octane healed heartbreak. We shook our heads and did not fix them.

On my way out, I held up the map. “For the glove box,” I said.

“Because sometimes,” he answered, “you should find your way without a voice telling you where to turn.”

I tucked it into the passenger seat like a second chance.

Spring eased into summer like a person choosing to stay. The townhouse became fluent in our names. Myra finished her mural and signed the bottom corner with a silver star. Rowan learned to make omelets and pretended it wasn’t witchcraft. Miles and I built a custody calendar that respected both our work and our children and our sanity, and the first time he picked up Myra from my doorstep, he didn’t step inside, and I didn’t step out, and neither of us overperformed decent. We were it.

My mother started bringing over recipes without lecture, which is the love language I always wanted from her, and my father wrote a poem about sparrows that wasn’t good but wasn’t untrue. On a Sunday evening, I caught them holding hands on my porch, and I didn’t tease. I bent the rules of my eye roll into a smile.

And me—on a Tuesday—standing alone in a room that used to be ours and then was mine and now was my kids’ sometimes and sometimes wasn’t anyone’s, I exhaled and felt the breath go all the way to the bottom of my lungs.

I pulled a box from the closet—one of the last unexamined ones. Inside, a tangle of picture frames and napkin rings I never liked and a vintage coffee tin my grandmother had used for buttons. Under all that, a notebook. My handwriting, early, enthusiastic. A list written in a different house, by a different woman.

Things to Build:

A marriage where both people tell the truth.

A home where our children never flinch at footsteps on the stairs.

A life that doesn’t require eating my own voice.

A way out, if I need it.

I put the notebook back. I checked the boxes in my head.

Later, when the kids were both out—Rowan at Cat’s, Myra at an art night I still think was a front for milkshakes—I sat on the back step with a glass of water, because some nights are meant to be remembered clearly. Fireflies auditioned with admirable sincerity. A neighbor practiced that trumpet again and—miracle of miracles—hit a note clean enough to make a stranger smile in the dark.

I pulled out my phone and wrote a message to myself in the notes app: The house is emptier. The heart isn’t. Then I added, Anger isn’t an engine. It’s a flare. You don’t drive by it. You steer because of it, and then you let it go out.

The front gate creaked. Jude didn’t announce himself. He doesn’t have to. He sits down beside me like the step issued him a license.

“Want to hear something wild?” he asked.

“That you finally fixed the receipt printer?” I said.

He held up a roll of paper like a trophy. “Justice,” he said. Then: “And I made biscotti I think you’ll actually like.”

“You’re determined to convert me,” I said.

“Only to the idea that happy doesn’t have to be loud,” he said.

We ate something with almonds that didn’t break a tooth. We said almost nothing. I leaned my shoulder against his without being coy about it. He leaned back without being proud. After a while, he turned his head and kissed me once, long enough to be true and short enough to be a promise.

My phone lit with a new text—Myra: We made a comet. Be back by 10. Rowan: Don’t wait up (which means please wait up). Miles: Did you get the school email about the end-of-year thing? I can take tickets if you do chairs. I texted back a thumbs-up to one, a heart to the second, a Chairs it is to the third.

I set the phone face down. The map in the glove box waited for the day I needed to choose the unadvised road. The mural glowed faintly through the window like it had learned to light itself. The town breathed with me. My chest didn’t hurt.

“It’s funny,” I said. “I used to think endings were explosions. Turns out most of them are doorways.”

“Or steps,” Jude said.

“Or maps,” I said.

“Or gas stations,” he added, because he is committed to his bit.

We laughed. We didn’t say forever. We didn’t have to. The moment didn’t need branding to be real.

I went inside to turn off lights in rooms we’d made messy in ways that didn’t require apologies. I paused at the mural and touched the small, messy star I’d painted in the corner.

Then I wrote one last line on a sticky note and pressed it beside the star so Myra would find it in the morning:

Fresh start: ongoing.

When fortune finally calls your bluff and freedom answers, you don’t make a speech. You make dinner. You show up to ballgames. You meet friends at gates and let them go. You kiss a good man slow. You paint walls. You salt water properly. You build a life you don’t need to defend.

You breathe. And then you keep breathing.

THE END

News

My Family Destroyed My Dream House At My Nephew’s Birthday, Then Called The Police On Me… CH2

Part I I cried the day I got the keys. Not the pretty kind of tears you dab at with…

Wife Flirted With Her Coworker Right In Front Of Me And Said, “If I’d Met You Before My Husband… CH2

Part I Your last morning of peace begins now. Wake up to the truth, Cara. The disposable camera clicked one…

My Parents Gave Me Up For Adoption At Age 10 Because I Was A Girl. When I Inherited A Fortune… CH2

Part I: If you’ve never watched a life get tallied like a ledger, come sit at my father’s dinner table….

She Came Back From Her Affair Acting Normal — Until One Step Into Our Bedroom Changed It… CH2

Part I It was 3:17 in the morning when she assumed I was asleep. I lay on my right side,…

I Was In Labour Begging My Parents To Take Me To Hospital They Left Me On Road Dad Said Die On Road… CH2

Part I: I was twenty-five when my body finally spoke louder than my fear. The first contraction took my breath…

“Why Can’t You Be More Like Her?” He Asked — So I Stopped Trying to Be Anyone Else. Now He’s… CH2

Part I My name is Irene Betts, and I learned the hard way that love doesn’t always go out like…

End of content

No more pages to load