Part I — The Reading

The mahogany-paneled office looked like the kind of room where verdicts had been handed down long before any of us were born. Polished brass, a Persian rug softened by decades of soft shoes, leather-bound case reporters that had not been cracked open in years but still performed authority like a well-trained actor. A clock with Roman numerals kept time with a patience that felt cruel.

I froze in the doorway. My husband stood beside the partners’ credenza, so smooth he could have been carved that way. He wasn’t alone. She clung to his arm—hair carefully disordered into perfection, lips bitten pink as if she had just remembered shame but decided against it. In her arms she carried a newborn, swaddled in muslin printed with tiny gray clouds. Their newborn. They had the audacity to smile at me. I suppose they had practiced that too.

“Mrs. Whitmore,” the lawyer said, clearing his throat as if it could clear the air. He was the junior partner, thirty-five and overeager, wearing a tie that wanted to be noticed by someone other than me. “I’m sorry for your loss.” He glanced at my husband and the woman and then at my face, as though trying to decide which weather pattern to dress for.

“We’re here for the reading of the late Mrs. Whitmore’s will,” he continued, less apologetic now that he was reciting the part that came with a script. “If you’ll take a seat.”

I sat. I folded my hands like a schoolgirl being graded on posture. I placed my handbag on my lap as if I needed something to anchor me to the chair. This was the moment my life fractured into “before” and “after,” and I was not going to ruin it with tremor.

Twelve years ago, I met my husband in a bookstore with a coffee counter in the back and a cat asleep on a display table like a divine endorsement. He had been charming in the way men are when they have decided you are the next story they will tell about themselves. He quoted lines to me—Baldwin then, Eliot later, always a well-timed Fitzgerald—and I was young and wide-eyed enough to believe love could be written like a novel if we turned the pages slowly. He said “children forever” and “loyalty” and “you and me against the world,” and I said yes in ways I had been taught were virtuous.

People think betrayal arrives with cymbals. In my experience, it starts like a leaky faucet. Late nights at the office. Whispers on the deck that ended as quickly as they began. The scent of perfume that wasn’t mine faint and then suddenly a fog. I confronted him once in our kitchen with its exact white tile—we were still on speaking terms then with the person I thought I was. He laughed the way men laugh when they have convinced themselves the rules do not apply. “Paranoid,” he said, and kissed my forehead like I was a child asking a bad question.

I swallowed it. I was afraid of being alone in a house that had been sold to me as a team.

Then the message arrived, not meant for me, flashing up on the laptop he had left open like mercy with bad timing.

She’s asleep. I wish you were here instead.

There it was. Proof. A knife slid between ribs so cleanly that what you feel first is the absence of resistance. I did not scream. That would have been a song he could dance to. I did not cry. Not where he could see. I smiled, and in that smile, I buried the woman he thought he had married.

Grief sharpens clarity. People think it dulls you—makes you drink or forget or sleep, but my mother had taught me to iron shirts while crying and make chicken soup through funerals. When my mother-in-law died, something in me hardened into purpose. She had been my ally in ways that confounded him. She saw him, the way mothers do, and still loved him enough to tell the truth. Over tea two weeks before the doctor said the word we had not been using—metastatic—she took my hands in hers and said, “If he ever betrays you, don’t fight him in anger. Fight him with patience. It’s the only way women like us win.”

I listened. If you are fortunate, a woman tells you the strategy manual before you need it.

I played my part with the accuracy of a surgeon. The grieving wife who stacked the sympathy cards on the hall table and wrote polite notes back, who kept wilted flowers fresh with a trim at the stems, who signed hospice papers with neat blue strokes, who lay pale lilies on the grave and did not throw herself on top of anything. People feel reassured by a particular quiet. I gave it to them.

And at night, when the house was sleeping, I sat at the desk in the office he liked to call “mine” and opened bank statements. I traced transfers and their careful descriptions—consultancy, vendor, move—to amounts that matched the new life I suspected he had promised. I learned his patterns—when he called her (after I said goodnight and the water started in the shower), what he bought her (shoes, yes, and the peach lipstick he loved on me once), where she had moved (closer to his office, because he had sold her on convenience and what he called “safety”). I say “learned,” but that makes it sound academic. It was muscle work. It was making a list every night and checking it off with the same satisfaction my mother-in-law had felt weeding a garden that looked like it grew itself from the street.

I knew her name before she knew mine. I knew she quit her job the week after he promised her comfort. I knew the lease on the previous apartment had been broken with a penalty. He believed himself generous. He had never studied a ledger as carefully as I had.

By the time the baby arrived, I was ready.

I found my lawyer weeks before the hospice nurse changed the morphine dosage and lifted her eyes to mine. Not his lawyer. Mine. My mother-in-law’s estate was vast. You could have lost a child in the list of trusts. She had been careful, and even in illness, she was meticulous. She wielded her power with the same exactness with which she peeled apples—clean rings and no waste. She had invited me into her office the month the doctors began to use euphemisms and asked me to bring the bank statements I had collected because she had come to trust my precision. “Show me,” she said. So I did.

She rewrote her will two months before she died. I knew because I encouraged her and because she asked for my eyes on the clauses that tethered virtue to structure. “I love him,” she said to the lawyer and to me, because you tell the truth to both people if you can. “And I know him. He’s never learned to say no to his hunger.” She signed with a steady hand.

The lawyer’s voice broke into the room like a light turned on. “To my beloved daughter-in-law,” he read, and the words sat heavy in the air, upholstered in years, “I leave the Whitmore estate in its entirety.” He cleared his throat, and not because of dust this time. “My son shall inherit nothing until he proves responsibility and loyalty. A review will be conducted in ten years.”

I felt, in the moment before reaction, the edge of the rug beneath my heels.

My husband shot to his feet with an absurdity that nearly made me laugh. “This is absurd,” he said. “I’m her blood.”

I tilted my head and met his rage with the economy it deserved. “She knew who deserved her trust.”

He opened his mouth and closed it again. He looked at the woman—to call her mistress felt too ornate for what she was; she was a symptom—and she clutched the baby tighter, as if a child were a shield and not a responsibility she had not yet finished imagining. The baby whimpered because new souls are sensitive to pressure changes.

“Mrs. Whitmore,” the lawyer said—to me, not to him, not to the woman—“if you have any questions, I can…walk you through the details.” Behind him, the senior partner’s portrait watched with the kind of benevolence paint can afford itself when it doesn’t have to live with any consequences.

“I’m sure you can,” I said, and felt the weight of the years lift off me not like a garment but like a ceiling.

I did not gloat. I had learned restraint from a woman who could tell you the truth about your dress and then fix the zipper. I did not raise my voice. That would have made it theater. I simply let realization dawn on him with the slow, sour light of morning after too much night.

That was only the beginning.

I left the office and called the bank. I froze the joint accounts, explaining in a voice I had learned from my mother-in-law that fiduciary responsibility is not a romance. I called my lawyer and filed for divorce the next day. The evidence of infidelity in a community property state is less about morality and more about clarity. But judges are human. The photos I had authorized a woman with a long lens to take—the hand on a waist coming out of an elevator, the ring-less fingers at a patio lunch that lasted three hours—had the quality of narrative even without captions. The text messages, subpoenaed, had more. The judge’s ruling came like a door click: I kept the house, the assets that had gone stealthily out, and custody of what mattered most to me, which was my dignity arranged within a new life that fit, finally, because I had built it around the truth.

She had thought she was stepping into wealth—that the room he had promised her smelled like new money and wood polish. She inherited his debt and his desperation and a temper that had been waiting behind silk. I almost pitied her. Almost. Pity is a ribbon women are asked to tie around our own weapons.

Now I sat in that office while the lawyer pretended not to hear the beginning of his “blood” argument, and I thought of my mother-in-law the morning she signed the new will. Of how she had put her pen down and looked at me across the desk where she had balanced our lives for years. “Patience,” she had said. “We sharpen it in time, and when we need it, it cuts clean.”

My husband’s mouth kept moving. I let the clock with Roman numerals drown him out.

Part II

The last conversation my mother-in-law and I had about money could have been mistaken for a recipe. We sat at her kitchen table while hospice moved discreetly in the hall, and she wrote on a yellow legal pad in the same neat print she’d taught all her children but only I had chosen to keep. “One part truth, one part structure, one part patience,” she said, smiling at her own joke. “Stir with a clean spoon. Bake until it holds.”

She had old money, the kind that made people use the words “estate” and “foundation” instead of “house” and “savings.” Her wealth had not turned into laziness. She read statements like some people read mysteries. It is a special kind of power, to have enough and also to understand the shape of enough. She had taught me slowly, as if she knew something about our future and wanted to make sure I could write it down.

“I was careless too once,” she said that day. “I thought ‘he loves me’ was structure. Then I learned it is rope unless you make a knot.”

We had been watching my husband spend in the way undisciplined people do when they are euphoric—big gestures with no ballast. The first things were little: a watch he did not need, a dinner reservation at a place where the waiters spoke assent in three languages, cash he called “tips” for a valet who did not exist. Then the transfers became bolder—the lease application fee addressed to a company name only a person who ran background checks would think to chase; a retainer to an “interior consultant” who listed a P.O. Box that could have been a closet.

I showed her. Quietly. Carefully. In the margins of our dinner conversations and in the tidy spaces between her doctor appointments, scanning and highlighting, because it turns out there is nothing like grief for creating time if you dare to use it for something other than despair. She listened the way she had taught me to, and she did not gasp. She picked up the pen and said, “Call Anna.”

Anna was her trust lawyer, seventy with hands that looked like she still cooked, brilliant behind glasses she never messed with. Anna took the files I laid out and arranged them into a story a court would understand. She called what I had done “due diligence,” and I liked the way those words sat in my mouth.

My husband did not notice the way we moved around him. That is the first rule of surviving a man who has convinced himself he is the center: never interrupt the story he is telling about himself; he will make it about your manners and not his actions. We quietly updated trustees. We amended at least one clause to account for new vulnerabilities. We created a schedule that would outlive my mother-in-law’s heart. She signed, not with vindictiveness, but with a look that said—more than anyone—she had finally developed proper pity for the girl she had been when she believed dominance was love.

“Make sure you think of what you want,” she told me. “Not just what you’re protecting yourself from.”

“What if they are the same,” I asked.

“They aren’t,” she said. “That’s a story men tell about us. Want to see the world you’re choosing? Put your hand on something you own and ask yourself if it’s yours because of fear or because it fits.”

I went to the house I had picked and placed my palm flat on the newel post at the foot of the stairs. I had chosen it because of the way light fell through the old window on the landing—poor resale logic, excellent life logic. I felt the wood, the faint hairline crack along the grain. That was patience too—the house had learned to flex with weather and not split. I wanted that. I wrote it down in my head in case I needed to recite it later.

At night I learned the tools he used. No woman I know was ever taught that financial software could be as intimate as a love letter; men had always been told this. QuickBooks, Mint, a spreadsheet that had been set up with a password he had once joked about in bed and thought I wouldn’t remember. I remembered everything now. The night I found the note in his phone—the one with restaurant names and hotel addresses written under the code “vendors”—I did not clip it to the printouts with an angry claw. I smiled because he had made me a neat little index.

The woman—the one who would later glide into a law office with a child named for an attention she would never again earn—had a public Instagram with a private smile. I did not follow her, because then it would be about relationship. I watched. Trips she could not have planned on her salary and vacations with dates that matched his “board meetings.” Posing in a dress I recognized by brand because he had once asked me if he could see me in something like it and I had laughed because I hated bows. The caption said “blessed.” I wanted to comment “funded,” but the patience recipe was taped to the inside of my skull.

People think you have to be cruel to do what I did. I was not cruel. I was precise. The work of undoing punishment requires precision. You learn to breathe when fear has wrapped itself around you like linen strips and someone says, “just one more pass with the scissors.” You behave around the patient as if they are the best version of themselves so they do not flinch and make the cutting more difficult.

I booked a photographer, recommended by Anna. “Tasteful,” Anna said, with the understated savagery women over fifty so often get to enjoy. “Discrete. Won’t bait anyone, won’t create a scene. Documentation, not performance.”

She wore flats and a lanyard with a badge that said Facility Services. She took photos the way I think surgeons take tumors—careful, efficient, without pretending there is art involved. When she handed me the manila envelope, it felt like the opposite of the one my husband had once brought home with classifieds circled in blue when we were something like happy. It felt like a new language I had finally earned.

The day we sat around the kitchen table—me, my mother-in-law now in her good cardigan, Anna with her hair in the soft bun that makes women look kindly, which deceives men into telling the truth—the will revision passed like a sacrament. It was spoken. It was taken. It was understood. My husband had always used his mother’s trust as a future loom. He would drape that cloth over his new table, tell himself he had woven it, convince the woman cooing at the baby that he was destined for this fabric. He would learn what it meant when a stitch is pulled.

I watched my mother-in-law sign. I have never liked the word “matriarch.” It sounds like a painting of a woman with a shawl. But I loved her then as whatever that word intends. She used what she had not to shame, but to shelter. She did not withhold emotion as a punishment; she delivered resources as protection. “You will not thank me properly while I am alive,” she said, cheerful and dark in that way women are when they know the road is ending. “So do not worry about it. Just live well. Wear shoes I would have disapproved of. Sleep in a house that allows me to haunt you with good sense.”

When she died, the house was full of people who brought casseroles with panko crumbs on top and stories about how she had held the church together with nothing but a pencil and the willingness to use it. My husband wept in large gestures. The woman did not come to the service. She sent flowers with a card that said “peace” in a font that had cost good money. I added it to the stack and later placed it at the bottom of the trash because you do not memorialize a lie.

After the funeral, he took my hand in the kitchen the way he had when he was still a boy and said, “We’ll be okay.” I put my free hand on the newel post and said, “We will,” and thought to myself that I had never been so ready to mean a sentence differently from the person hearing it.

Part III

The office was an artifact. The Whitmore family had been clients for two generations, and the firm liked history too much to redecorate. It was useful in this one way: the walls had absorbed enough male voices that mine sounded louder and deserving by contrast. The junior partner coughed again, and then read. There is a special tone lawyers use when they announce money’s intentions. It is half-ecclesiastical, half arithmetic.

“To my beloved daughter-in-law, I leave the Whitmore estate in its entirety.”

The way the “my son” clause came—slow, deliberate, patient—was not for drama. It was for structure, for the satisfaction of a woman’s voice traveling from beyond a grave into a room where she had performed and been denied for years.

“My son shall inherit nothing until he proves responsibility and loyalty. A review will be conducted in ten years.”

My husband made a noise like a car failing to start. He looked at me as if I had written it myself. I hadn’t, but if I had, I would have chosen the same words.

The woman’s arms tightened around the child. For a second, I thought she would say the baby’s name loud in the room as a claim—as if the air could be notarized—but she didn’t. The newborn’s mouth opened in a perfect red O and then closed again. He would be hungry soon. Reality has a way of calling us back from performance.

“Now, as to the trusts,” the lawyer said, hedging, as if he had just announced a storm and now wanted to talk about umbrellas. The numbers spun quietly, a well-constructed machine that could feed a life and starve a dependency. I did not need the details then. I had chosen patience again. There would be weekends and clauses enough.

My husband stood. “Absurd,” he said, louder, as if decibels could make documents change. “She was sick.”

“She was careful,” I said. I had chosen to speak only when necessary; this sentence felt like someone had set a wine glass down and I had put a coaster under it.

You must understand: I loved my mother-in-law more than I ever loved the idea of him. I do not tell that truth to shame either of us, but to honor the equation. He had been charming. She had been instructive. He had been story. She had been structure. When people asked me what kept me in the early days, I used to say “love.” Today I would say “manufactured hope and youth.” When people ask me what saved me in the end, I say “a woman with a pen.”

We filed the paperwork quietly. I moved through the house like I had every day for years and saw my own fingerprint rise into relief on every surface. It is a strange feeling, to recognize ownership as a verb. The past years had made me practice it during long nights when I believed nothing could change. The present made me perform it in court. The future would let me enjoy it.

His lawyer wrote to mine the next morning with a letter that tried to sound outraged and instead sounded like a man late to an exam. The divorce petition slid across the desk. He hired a PR firm, which told him to stop hiring PR firms. The woman—the symptom—found herself making lists she had never thought to make: pediatrician, sleep schedule, formula brands. She had always thought love was a blanket; now she learned it is also a burp cloth. It was none of my business. That was the gift of what my mother-in-law had done: my life could stop being about him.

In court, the judge looked like a man who had learned to wear distance. He looked at the photographs and raised one eyebrow. He looked at the text messages and did not raise anything. In the end, rulings are as much about weather as law. This judge was in the mood for a wind that day. I kept the house by right and by narrative. The accounts that had skittered away came home. The car he had called “yours if you want to look frugal” became mine with the same smugness he had once thrown at me. His counsel argued about lifestyle and I argued only about facts. The judge liked facts.

I told you—I almost pitied the woman. He promised you a room in a house where the cook had died, I wanted to say. He promised you a seat at a table where you will be the topic a month after you leave. He promised you a safety net he did not weave. She tried to stare me down in the parking lot once with a look that I recognized from the mirror in my twenties. I nodded at her and got into my car. She needed a friend older than me. I could not be it.

This is the part where people expect a speech about female solidarity. I believe in it. I do not believe in wasting it where it cannot do any good. Some women need us to be kindling; some women need us to be distance. I chose patience again. I suspect she will one day understand that was a version of kindness.

When I stood in the kitchen the night after the bank manager shook my hand, I could feel my mother-in-law in the house. Not in the silly horror-movie way—no draft, no clanging—but in the structure’s relief. Houses know when the burden has stopped being malignant. The newel post felt warm under my palm. I said out loud, because I could, “I can live here,” and expected no answer because I wasn’t waiting for a man to give me one. The shape of the sentence gave me more relief than any vow he had ever made.

I slept in the middle of the bed with the window open and the air came in smelling like rain and newspaper ink, and I dreamed of nothing at all.

Part IV — The Litigation and the Leaving

The first hearing was administrative in the way the official beginnings of endings often are: a judge who had learned to make small faces into no faces at all, a clerk with a voice that could lull you into confessing, a docket that made our names into numbers before lunch. He asked if there were any children of the marriage. “No,” I said, and watched the relief flit across his features in spite of himself like sunlight through blinds. He asked if there were interim orders needed. “Only that the respondent be enjoined from further use of community funds for non-marital purposes,” my lawyer said, and slid the binder across the table.

We had given the binder a nickname: The Atlas. It was heavy enough to anchor a door, clean enough to make a partner nod. Tabs labeled in my mother-in-law’s block letters—blue for account numbers, red for transfers, yellow for photographs, white for the inevitable apologies stitched together by someone who’d never been taught to apologize properly.

The judge flipped to the red tabs. “Dissipation,” he said, not as a question. He signed the temporary restraining order against spending like he was stirring cream into coffee. My husband’s attorney objected for the record in a tone that had once been called “spirited” at debate tournaments. The judge didn’t look up. “You’ll get your day,” he said. “Today is documents.”

Outside, on the steps, my husband tried to turn gravity into a scene. “You’re not going to win by embarrassing me,” he said, sotto voce, jaw set the way he sets it for photos he wants other people to admire.

“I’m not trying to embarrass you,” I said. “I’m trying to stop the bleeding.”

He laughed as if I had handed him a line he could make charming in a room. “You always did prefer a metaphor to a kiss.”

I thought of the baby in the law office, the muslin clouds. “You always did prefer a new audience to the truth.”

He leaned in. “You’re smug because you think you’re your mother’s favorite,” he said, and the slip was so tidy I almost smiled—his mother, always and forever, even in the possessive.

“She made a will,” I said. “Not a play.”

Divorce is rarely one big fight; it is a series of small ones dressed up in Latin. Interrogatories. Requests to Admit. Equitable distribution. My lawyer, a woman named Ruth who could juggle flaming pens and make it look like meditation, led me through each stage as if we were staging a play I hadn’t asked to audition for but could perform competently.

We hired a forensic accountant with salt-and-pepper hair and eyes that had seen every way men try to call a beaker a vase. He sat at my dining room table with a calculator the size of a book and went line by line, murmuring like a priest. “Here,” he said, tapping a series of $4,999 transfers that had been timed around bank monitoring thresholds. “And here.” He circled a check written to the interior consultant with the P.O. Box, who had suddenly become, during discovery, a limited liability company with no members named. He made a neat list labeled “Marital Waste.” It read like a restaurant menu for the very hungry and the very careless.

“They’ll cry ‘lifestyle’,” Ruth said, flipping pages. “Don’t worry about that. Judges know the difference between steak and a chandelier.”

At mediation, his lawyer tried to make charm do the work of math. “She was cold,” he said of me, as if the mediator were my grandmother leaning in at Thanksgiving. “He was lonely.” The mediator—a retired judge with a face like a soft door—did not write that down. He wrote the numbers. When my husband said “I put her through school,” the mediator asked, “Where?” and when he said “I built that house,” the mediator said, “With her mother’s money,” and the silence after had the quality of a well-cut fabric: it draped over everything.

We settled three pieces in an afternoon that left us both brittle: the house came to me clean, with a quitclaim deed to be signed the next morning in front of a notary with a penchant for humming; the accounts came home like dogs who had been called with the right name; the cars were split without theater. Everything else—art, the investment accounts he’d used as if they were tips jars, the club membership he would no longer need because I would no longer pay for his shoes—went to judgment.

In courtroom three, the judge’s patience had the quality of a seasoned gardener’s. He didn’t need to declare victory over weeds; he simply cut them at the base and waited for air to do the rest. “Given the demonstrated dissipation,” he said, eyes flicking to my husband’s counsel and then to the Atlas, “the Court orders an unequal division in favor of the petitioner.” He listed percentages. The numbers made a sound in my chest like a door sliding into a lock it had always been meant for.

“When can I be done?” I asked Ruth afterward, in the hallway where the linoleum had been scuffed by generations of men learning that consequences are heavy.

She smiled like a woman who has learned to ration her good news. “Soon,” she said. “Soon has a lot of paperwork, but it’s a real word.”

I moved through the house and unlearned the way I had lived in it for years. I took his tailored suits to the cleaner to be boxed, not burned—anger leaves soot, patience does not stain. I donated the cookware he had insisted we needed for dinner parties and kept the cast iron I had cooked eggs in at 2 a.m. the night my mother-in-law sat in my kitchen and told me we were going to win slowly. I moved the portrait from the stairwell—an oil he’d inherited of a Whitmore man in a cravat who had probably bullied horses—and replaced it with my mother’s needlepoint of a crabapple tree. I bought rugs that did not whisper money in rooms where I wanted to hear laughter.

I found a printout of a menu from the restaurant where he had, apparently, felt a certain spectacular joy last spring—$500 wine, a thing described as “foam,” an entrée that read like a dare. I put it in a folder labeled “History” and slid it into the back of a drawer where I kept the warranties. I wasn’t collecting trophies; I was curating prevention.

In the week after the decree was entered, I sat with Anna to go through The Will again under quiet light. “You’re trustee now,” she said, pointing with a pen. “That means you get to be the adult in the room. You’re very good at that. It also means you get to choose your rooms. You’re not obligated to stay in any you don’t like.”

“I don’t like many,” I admitted. “Yet.”

She laughed softly. “You will.”

“What about the ten-year clause?” I asked. “The review.”

She took off her glasses and cleaned them with the end of her sweater. “Your mother-in-law was not a woman who believed in eternal condemnation,” she said. “She believed in consequences and time. In ten years, if he can prove responsibility and loyalty, if he can demonstrate that he has learned to earn not extract, there is a mechanism for reconsideration. It is not a promise; it is a challenge.”

“And if he fails?”

“Then the structure holds,” she said simply. “She designed things to survive both outcomes. That’s what wealth should be for.”

I rested my palm on the legal pad. “He’ll try to weaponize that clause,” I said, not with fear but with the clarity that had become my new inheritance. “He will tell that woman there is a clock.”

“Let him,” she said. “Clocks are loud. Make your house quieter.”

He moved out in theatrical stages: a box of shoes, a row of suits, an espresso machine he had never learned to descale. Each time he left with something, he tried to leave with something else—in the air, in the way he spoke my name as if it were a possession. When he came for his books—the Baldwin, the Eliot, the Fitzgerald that had once convinced me he knew how to be decent—I took the ones with my notes in the margins out and put them on my shelf. He could buy his own copies with empty margins.

He sent two emails in the first month that seemed like apologies to people who had never had to mean the word. Subject lines: “Closure,” “For the Record.” They read like a man trying to narrate himself out of a hole. I was lonely. You were distant. My mother played favorites. I printed them because paper teaches me not to let my anger be the only archive. Then I wrote back Please direct all further communication through counsel. A sentence is a boundary if you put the period in the right place.

She texted once. The number showed up as “Unknown,” though of course there are few unknowns left in the world if you have patience. This isn’t what he promised, it said. For a long minute, I imagined writing a wisdom that would save her a year: Men promise rooms they have not checked the foundation of. I didn’t. She needed an older woman, not the woman.

Instead, I replied: There is a child. Make him pay for diapers on time. Make him show up for pediatric appointments on time. Make him set up a 529 and put a note in your phone every month. Don’t fight me in your head. Fight for your own math. You’re going to be tired. Eat protein. Save $20 in a drawer. It will not be enough. It will be something.

She wrote back a single word: Okay. Sometimes okay is a prayer.

At the hearing that finalized the property division, the judge spoke numbers and called them fair and then did something I did not expect. He looked at both of us—me, steady; him, fraying by choice—and said, “This is one of those cases where the law occasionally matches the story. Don’t count on it. Live like you have to keep telling yours anyway.” The court reporter looked up then, startled by insight where she had expected only language.

Ruth handed me a copy of the decree in the hallway and squeezed my hand. “You did this well,” she said. It wasn’t praise exactly. It was recognition.

I went home and made myself a dinner with three colors in it because that’s what my mother would tell me to do, and I ate it at the table my mother-in-law had bought at a market the year she turned fifty and told me she was finally getting good at asking for the check. I poured a glass of the good wine she used to save for occasions and drank exactly one and a half glasses because control is not a scold, it is a seat.

That night, I climbed the stairs barefoot and stood at the landing window, the light bending across the banister in the shape that had made me buy the house in the first place. I slept with the window open. In the morning, the house smelled like rain and the daily paper and the lemon oil I’d used on the banister.

I took a notebook to the desk that had been a battlefield and wrote three lists with a pen my mother-in-law had lifted from a fundraiser and kept because she liked the rollerball. The lists were labeled: House, Work, Joy.

Under House, I wrote: fix the crack in the plaster above the pantry; choose paint that does not apologize; put the portrait in the attic where ghosts go to make better choices.

Under Work: ask for the project I want, not the one that needs saving; teach the junior associate the file naming convention so my future brain loves me; at 5 p.m., leave twice a week.

Under Joy: buy the shoes she would have disapproved of; host a dinner for the women who fed me during hospice; dance in the kitchen with someone who likes the song as much as the step.

I put the notebook in the drawer with the warranties and felt, for the first time in months, the act of keeping something for later feel like hope instead of delay.

He called once in the fifth month, from a number my phone labeled but my stomach already knew. “My mother loved you more,” he said, as if the sentence were a weapon.

“She loved me differently,” I said. “She loved me enough to hand me the pen.”

He laughed then, a cracked version of his bookstore laugh. “You think you won.”

“I think I learned,” I said.

He hung up.

I went to the landing window and put my palm on the newel post and thought of the best part of my mother-in-law’s recipe: patience hardens into protection if you pour it into the right mold. The right mold had been a trust. The right mold had been legal advice. The right mold had been my own spine.

I replaced the voice on the speaker with music. The house and I listened to a woman sing about getting out and staying out and how the light looks different when it’s yours.

The day the decree became a piece of mail in my box, I took my mother-in-law’s pearls out of her jewelry box—the one with the velvet that makes everything feel like it was meant to be touched—and put them on with a sundress the color of figs. I went to the bakery she liked where the clerks call you “love” and bought two of the croissants they only ever make on Thursdays. I took one to the cemetery and ate it sitting on the grass near her name, smiling at the indecency of crumbs near such polished stone.

“You would have approved of the Will and disapproved of the dress,” I told her. “It’s a solid day.”

The woman who had brought the baby into the law office passed me then with a stroller and a look on her face I recognized: exhaustion worn at the edges, not martyrdom, with a stripe of stubborn in the middle. I nodded at her. She nodded back. It wasn’t forgiveness. It was an acknowledgment of math.

On my way back to the car, I caught my reflection in the window of the florist on the corner, pearls and fig and a posture that had nothing in it of apology. The woman in the glass didn’t look like a winner. She looked like a woman who had built herself a room she could stand up straight in.

That night, under the landing window, the light bent across the banister the way it always had, but I noticed it differently. Now, when people came over for dinner, they would stand at the bottom of the stairs and see what I see every day: a pattern cast by a window, a newel post smoothed by hands that refused to tremble, patience poured into a structure that would outlast bad weather.

At the sink, the water ran. I turned it off and listened to the quiet. It didn’t feel like absence. It felt like a room finally empty enough to fill with what I chose next.

Part V — The Review and the Window

The first year after the decree, I learned how to live in a house that did not require an audience.

I painted the kitchen a white that did not apologize for being bright. I took down the brass chandelier that had hung like a threat over the dining table and put up a fixture made of paper and wire that softened the room into welcome. I held the dinner I’d written on the list: eight women with hands that had fed me through hospice and one more who had stood at my shoulder on courthouse days and said nothing when saying nothing was the useful thing. We ate chicken roasted with lemon and salt, and potatoes my mother-in-law had taught me to score for crispness, and green beans in butter because grief requires butter even when it’s over. After, I stood at the sink with Brooke, who runs the only honest bakery in a four-mile radius, and we washed dishes in a rhythm that made conversation unnecessary.

“You look different,” she said, not meaning clothes.

“I am,” I said, not meaning personality.

Work became a house too. In the absence of managing my husband’s narratives, I had space for actual architecture. I said no to clients who wanted my hours more than my mind. I asked for a project because I wanted it, not because it needed saving. I taught a junior associate how to name files in a way that made her future brain love her. I left twice a week at five, as promised to a legal pad, and sat on the porch with tea that tasted like something other than survival.

She texted twice the first year. The number still showed as Unknown. We’re at Children’s. He has RSV. Then later: He didn’t come. The baby cried for him and he didn’t come. The first text I replied to with the name of a pediatrician my mother-in-law had trusted, even though RSV is not something you gentle into submission with a name. The second I did not answer; she needed a friend older than me, and I had learned to stop auditioning for roles that weren’t mine.

The baby became a boy as stubborn as a new season. I would pass them on the sidewalk sometimes, him dragging one foot like it was a friend, her purse bumping at her hip the way bags do once you’ve put snacks and wipes and the weight of other people’s choices in them. Once, when he threw himself down on the grass under my crabapple tree and refused to go any farther, she looked up and caught my eye with the precise facial expression of women who know there won’t be any talk, and we laughed. She had learned to keep single syllables for later.

He spiraled, of course. Men who have counted on the weather to be flattered will stand outside in storms and complain about the sky. There were months of performative penance: “I’m working on myself,” he wrote to mutual friends and the parts of social media that burp at the scent of contrition. There were months of rage dressed as a better vocabulary. He moved three times in a year, each lease shorter than the last. He took a job selling the idea of him to people who did not know him, then lost it because people who do not know you learn quickly when you do not show up. He made a speech at a bar once and thought I’d be there and I wasn’t. His calls to my phone dwindled from “You can’t be serious” to silence.

What I didn’t expect was how the vacuum would change the house. I could hear clocks again—not the big one in the living room with Roman numerals, but the small ones: the radiator’s occasional tick, the distant traffic bloom at rush hour, the music of my own steps on the stairs when I wasn’t trying to walk like someone other than myself. I learned which floorboard creaked under the third stair because of a nail going soft and hired a man named Ángel who made magic with wood. “Houses breathe,” he told me. “You listen and you fix the parts that get tired.” I could have married him for that sentence alone. Instead, we danced in the kitchen one night, badly, when an Aretha song came on the radio, and then laughed so hard we had to sit down.

It is a particular luxury to learn desire after you stop needing rescue.

The foundation I created in my mother-in-law’s name began as a line in the will and became a room in the world that I could walk around in. We called it the Whitmore Table because money is only ever a table for better meals. We wrote its mission in plain English: to teach women the patience recipe—in money, in law, in survival. Tuesday nights we held clinics in the church basement where she had once kept the books, fluorescent light unforgiving and perfect. We handed out binders with tabs that said BANK, WORK, HOUSE, and a cheap calculator each. We brought in Ruth to explain community property like a vocabulary lesson and Anna to explain trusts without being obscene about it. We printed worksheets that asked women to list one thing they wanted and one thing they were afraid to ask for. We told them not to apologize. We put snacks on the table. It was revolutionary.

A woman named Chrissy stood in the doorway once, shaking like she’d been told to by a man, and left three hours later with tabs labeled in her own handwriting. “What if he finds it,” she asked, whispering like the wall was a person. “Then you buy another binder and hide it somewhere else,” I said. “Then call me. We have more than binders.” She nodded. She put the first one inside her purse and left the second one here. We had created a lost-and-found for patience.

The press called it philanthropy. I called it an apology to the girl I had been when I thought hope could be set in a vase and called décor.

The clause came due before the decade did. Word travels in families even when you don’t send the invitation. “Ten-year review,” he said, breezy, when he called the foundation office in year nine and asked to schedule a meeting with the trustees. “I’ve changed. I can show you.” He used the phrase “my mother’s intentions” as if intention were an answer key.

We set it for June because patience in June feels like mercy and in January feels like punishment. The boardroom looked exactly like the first one, except this time I sat at the head and no one clung to anyone’s elbow. Anna sat to my right stiff-backed and bright-eyed, and to my left was a woman named Fatima who runs our clinic nights with an efficiency that would shame a surgeon and a florist.

He came in wearing a suit that had fit him better once and a smile that had convinced him of things too many times. He placed a folder on the table. “I’ve put together a packet,” he said, and for a ridiculous second I remembered our kitchen eleven years ago, two wineglasses, his hand on the Romeo and Juliet shelf like he could pick the right story if he just reached high enough. He nodded at the documents anyway. “Letters from clients. Sobriety chip.” He let that sit like a marionette bow. “Pictures of…us.” He meant holidays with the boy; he did not mean me.

The photos were beautiful: the child with a gap in his teeth and a gaze that promised trouble in the best ways, and the man standing next to him trying to learn how to be in the frame without expecting it to-love him back.

“Tell me about money,” I said. “The will mentions loyalty and also responsibility. It mentions review, not forgiveness.” I used Will words because they tend to clang in rooms like this. They sound like fair weight.

He gripped the chair back tighter than necessary. “I’ve had a difficult decade,” he began, and I waited to see if he would go where men go—anger disguised as confession, charm disguised as change. He tried both. “I have regrets I cannot count,” he said, a sentence designed to make me hand him an abacus. He wanted me to ask which regrets so he could give me the edited reel.

“Tell me about stopped behavior,” I said. “I’m not a priest. I’m a trustee.”

He blinked. It was satisfying to watch him try his old keys in locks that had been changed. “I don’t…take what isn’t mine anymore,” he managed finally. He looked at Anna for approval and found none. “I show up,” he added, and I nodded because it’s not nothing. “I haven’t asked…her—for me—for money in months. We split holidays. I…pay the child support,” he said, with the air of a man announcing a plot twist. “On time.”

“Do you take the child to the dentist without complaining,” Fatima asked, pouring water with kindness she did not intend to remember later. Her daughter had been a toddler when she left, and she knew the kind of man a man actually is by whether he thinks pediatric dentistry is beneath him.

He bristled because bristle is a habit. “My mother wanted me to…grow,” he said. “She wouldn’t want me poor.”

“Men like you always assume the challenge was written for them to pass,” Anna said calmly. “Your mother wrote that clause to restrain greed, not reward it. This is not a syllabus. There is no grade inflation.”

I thought of my mother-in-law, in her good cardigan, smiling at the thought of the three of us on this side of a table talking like this. I thought of the clause, and what she had intended from the grave: not to leave the door open for hope like a draft, but to build a window that could be opened if air was needed.

He looked at me, tried the last thing men try: “You loved her,” he said. “You know.”

“I did, and I do,” I said. “Which is why you will not be allowed to call what you’ve done enough when it is simply what you owed. Come back in ten years if you have made a life that doesn’t require a woman’s money to keep you from sinking.”

He stood. His jaw worked the way it always did when he wanted to say something useful and the sentence had not been born yet. He picked up his folder. He looked at the child in the photos on the table and pressed his lips together.

At the door he turned and did a dangerous thing—told the truth: “I thought it would feel like victory,” he said. “The day she died.”

“It never does,” I said. “Not for good men. Not for the other kind, either. It just feels like work.”

He left. We sat quietly, three women in a room that had once been built for men. Finally, Fatima said, “Well,” and we laughed, the kind of laugh that breathes out centuries. We wrote the review minutes in plain English: No disbursement. Encouraged continued responsibility. Clause remains potential, not promise. We ate ginger cookies that Anna had put in a tin between us because old women always have snacks when they intend to tell you the truth.

In July, at a clinic, a woman came in with a bruise on her forearm the color of regret and asked if the foundation covered car seats. “We cover plans,” I said. “Sometimes they look like car seats.” She left with a binder and a list and my number on a card. She reminded me of the woman at the law office years ago—hair careful, smile careful, arms careful around something that does not care for carefulness. Maybe she was her. It didn’t matter. Women arrive in archetypes and leave as themselves.

I had dinner with a man who knew how to ask questions and liked answering mine. He was not Ángel, though Ángel would always get the first good peach in summer because he had saved the banister. This man ate with delight. He said “I don’t know” when that was the truth and “I was wrong” when that was too. We danced in the kitchen again once, less badly. The paper and wire fixture swayed and then righted itself. I wrote “love that looks like help” in the Joy column of the legal pad because there is a difference between writing it again and writing it for the first time.

I visited my mother-in-law’s grave in August with a bouquet of dahlias that looked like women gone dangerous. I told her about the review clause and her son’s folder and how I had said the sentence about work. I told her about the Table and the binders and the Tuesdays. I told her that the lesson about patience still worked in a world that did not deserve it. I told her I was tired and that tired felt different now; it felt earned.

I went home and lay on the couch and fell asleep with the window open. In the late afternoon, the landing window performed its trick again—light bending with more mercy than it needed to. I woke and went to the stairs because that is what I do now when I need reassurance: I look at the shape of a familiar angle and I put my hand on wood made soft by years and I count patience as a kind of strength.

The newel post told me, as it always does when the light finds it, that the house will hold.

The last time I saw his mother’s pearls, they were around my neck at the foundation gala we put on not to raise money—we had enough—but to raise volume. “Financial literacy,” people call it, as if it were a nice-to-have, like knowing the capitals of countries. I call it a map out. I gave a speech that did not mention love. I didn’t need to. Everyone in that room had been taught by someone that love was supposed to keep you from needing a map.

A woman whose name I did not know took my hand in the bathroom and said, “Your mother-in-law would be proud,” and I said, “Yes,” and neither of us cried because the line for the mirror was moving and we both needed to blot.

At the end of the night, I went home, took the pearls off, and set them in their velvet bed in the drawer where I keep warranties. I pulled the notebook out and added to the Joy column: teach a girl to ask her bank a question she didn’t know she could ask. In House, I wrote: refinish the stairs when you have time; they could be even more beautiful.

I poured a glass of water and stood at the landing window in bare feet. Outside, the evening moved like it had its own list. Somewhere in the neighborhood a baby cried and then was picked up and stopped—evidence of a different story being written at the speed of care. Somewhere else a woman laughed at a joke she had written herself. My house breathed. I listened.

He might come back in ten years with a better folder. He might not. The clause would still be there, not a promise, not a threat, just a window that opened if the room needed air. My job was not to hope. It was to steward. It was to watch the light and learn its pattern and write it down somewhere I would not lose it on hard days.

I ran my hand along the banister. The wood was smooth from the hands of women who had decided to keep going. It is an odd relief to realize that the story is over not because there is a big sentence to end it, but because the room has filled with enough of your own life to make punctuation unnecessary.

I turned off the downstairs lights and climbed the stairs holding onto the newel post for balance because even houses built with patience require your hand sometimes. At the landing window, the light bent and became a stripe on the wall.

I smiled and went to bed.

News

“We Left My Stupid Husband Miles AWAY From Home as a JOKE, But When He Returned It Was NOT Funny…” CH2

Part I I can tell you the exact moment I should have trusted my gut. It wasn’t the tight smile…

Sister Announced She Was Pregnant With My Husband’s Baby at My Birthday—She Didn’t Know About the Prenup CH2

Part I The florist had crammed the hotel ballroom with white roses because “thirty deserves a thousand blooms,” according to…

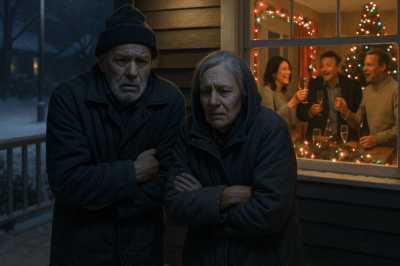

I Found My Parents Locked Out With Blue Lips While My In-Laws Partied Inside…So I Made Them Pay CH2

Part I — When Help Knocks and the Locks Change Robert said it like he was reporting the weather. “My…

Parents Chose a Vegas Poker Party Over My Surgery — My 3 Kids Left Alone, and I Finally Cut Them Off CH2

Part I: The Line in the Doorframe I told the bank we were done. That was the sentence that cut…

WRONGFULLY JAILED FOR 2 YEARS – NOW I’M FREE, BUT EVERYTHING I BUILT IS GONE CH2

Part One: The Strip-Mall Law Two years of my life were stolen because I was walking home from school. That’s…

Black Nurse Insulted by Doctor, Turns Out She’s the Chief of Surgery CH2

Part One: Night Shift The night shift in the emergency department had a sound all its own—a layered hum of…

End of content

No more pages to load