Part I

I was arranging lilies in the blue vase Richard bought me in ’83 when I heard my daughter-in-law’s voice carry from the kitchen like a knife wrapped in silk.

“This useless old woman is going to eat through all our money. We need to throw her in a nursing home.”

The stems slipped in my hands. Water kissed the rug. I stayed behind the doorway—not hiding, exactly. Listening. It’s a dangerous skill for a woman my age; people forget you still have ears, and teeth.

“I don’t know, Lilia,” my son said. Blaine’s voice had the same tremor it carried when he was five and swore the broken lamp jumped. “She’s still my mother.”

“Your mother?” Lilia laughed, all glass and edges. “Blaine, wake up. She’s a burden. Look at this house. She shuffles around like a ghost. We’re paying for her food, her medications, everything. For what?”

For forty-two years of partnership with his father, I wanted to say. For night shifts at the plant when a foreman called in sick. For Sunday nights spent balancing payables on the dining table while Richard pretended the Raiders would stop breaking his heart.

“She doesn’t even know how to use a computer,” Lilia continued. “She can’t manage any of Dad’s affairs. Face it—she’s useless and expensive.”

Six months. That’s how long it had been since I buried Richard—my husband, my partner, the only man whose silence ever sounded like a promise instead of a threat. I could still hear the organ. I could still smell the lilies on his casket. Blaine had put an arm around me at the graveside and whispered, “Don’t worry, Mom. I’ll take care of everything.”

Everything, apparently, included me.

“There are some nice facilities,” Lilia said, and I could hear the catalogue pages turning in her voice. “She’d have people her own age to talk to. It would be better for everyone.”

Better for everyone. Better for them. Worse for the woman who taught him how to tie a tie for his first job interview, who held a stopwatch while he ran laps to make the JV team, who convinced his father that a little nepotism is still nepotism even when it involves a summer on the factory floor.

“I suppose you’re right,” Blaine said, and the sound of it cracked something in me that had survived labor and layoffs and the day Richard came home with stitches and a lie about how machines “get playful sometimes.”

“She does seem lost without Dad,” he added, like grief was a malfunction to be corrected by relocating the problem.

I thought about the papers Blaine had pushed under my pen two days after the funeral. Legalese, he’d called it. Formalities. “Dad would want me to handle everything now.” I’d signed with a hand that wouldn’t stop shaking.

What Blaine didn’t know—what neither of them knew—was that Richard had been clever in the way quiet men learn to be after decades of counting screws and freight and disappointments. Long ago, he’d structured Hartwell Industries so that I owned seventy-five percent. Operational control, shadows, speeches—that could be Blaine’s. But the company? The vote that mattered? Mine.

I let them believe the lie because it was easier to play the widow who couldn’t find the settings icon. Easier than watching, too clearly, what my son was becoming.

“When should we start looking at places?” Blaine asked.

“I’ll make some calls tomorrow,” Lilia sang. “The sooner the better. I’m tired of tiptoeing around her.”

Around me. In my own house.

Footsteps approached. I climbed the stairs with a care that wasn’t fear so much as precision, the way you move when you know the world you built is being inventoried for parts. In our bedroom—my bedroom—I sat on the edge of the bed and stared at the wedding photo on the dresser. Richard smiling like he’d outsmarted the sun.

“They don’t know, do they?” I asked his face. “They have no idea what you really left behind.”

He hadn’t wanted to talk about death in those last weeks at St. Mary’s. But he made me promise. If Blaine ever treated me poorly, I would use what he left. I would not let anyone—anyone—push me around.

I had meant it then in the way you mean vows when you believe you won’t have to test them. By breakfast, I meant it like a command.

Blaine had “gone to the office” (my office), so it was Lilia who played emissary across my toast.

“Sloan, honey,” she said, a smile so bright it made my teeth ache. “We need to talk.”

“I’m listening,” I said, buttering.

“We’ve been thinking about your living situation. It must be so lonely in this big house.” She gestured, as if the walls were eavesdropping. “We found some lovely senior communities. Activities, friends your age—you might enjoy it.”

I looked at her face, really looked. She was beautiful the way money can make women—polished, prepared, practiced. She had always worn that appraisal in her eyes. I had mistaken it for admiration.

“When?” I asked.

She blinked. “Well—next week. I’ve already scheduled a tour for Thursday.”

Of course she had. “You’re not upset, are you?” she added, suspicion peeking through the lace.

“Of course not, dear,” I said, and smiled the polite smile I’d worn all winter. Inside, Richard’s voice: Don’t let anyone push you around, Sloan.

By Thursday afternoon I had a room at Sunset Manor—a beige box that smelled like disinfectant and canned hope. “Temporary,” Blaine murmured, setting my two permitted suitcases on the bed. He didn’t meet my eyes. “Just until we figure out long-term.”

Three weeks passed. My room smelled like someone else’s mouthwash. Mrs. Chen in the common room played solitaire with a deck missing the queen of hearts. The maple in the courtyard turned the same red as the one Richard and I planted in ’79, but the air didn’t taste like our October.

“You’re the new one,” said a woman sliding a walker like she’d taught it obedience. “Family dump you here, too?”

“Something like that,” I said.

“I’m Eleanor,” she said. “Thirty years I raised my kids. One tumble and I’m a liability.” She snorted. “They always have their reasons.”

“What did you do before this?” she asked, easing into the chair beside me like she owned it.

“I helped run a business,” I said. “With my husband.”

“What kind?”

“Manufacturing. Industrial parts.”

“Well,” she said, eyebrows hopping. “Important.”

“It was.” I watched three men fight over the remote without saying any words that meant anything. “My son runs it now.”

“How’s that working out?” she asked, as if she didn’t already know.

“Not well,” I said. I’d been getting quiet dispatches from Marcus, our old attorney—the kind of man who does his best work in the spaces between things. Blaine had cut legacy suppliers to chase margins, laid off the men who could hear a machine lie, approved a “bold new line” no customer had asked for.

That evening I used the hallway pay phone. The line hummed like an old fridge.

“Mrs. Hartwell,” Marcus said, crisp as a starched shirt. “I’m glad you called. We have to discuss Riverside.”

Riverside—fifteen years of revenue and Christmas cards.

“What about it?”

“Your son terminated the contract yesterday,” Marcus said. “Said he found a better opportunity.”

“What opportunity?”

“A startup with no track record offering fifteen percent higher margins. Their capital stack is already wobbling.” He paused. “This could be… significant.”

Richard’s voice again: The most dangerous time is when grief is steering a novice.

“Document everything,” I said. “Every contract he cancels. Every hire he fires. Every errand he runs in the company’s name. Quietly.”

“Of course,” Marcus said. “One more thing. Your daughter-in-law’s been… curious about your personal assets.”

I smiled though it tasted like tin. “Of course she has.”

He continued, “She asked about stocks, bonds, property outside the estate. I didn’t—”

“Don’t,” I said. “And start the paperwork we discussed.”

When I returned to the room, my roommate, Mrs. Patterson, sat on the bed holding a letter like it had insulted her.

“My grandson,” she said. “He keeps promising to visit. New job. New car. Too busy.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it in the particular way women mean it when we recognize the shape of each other’s wounds.

“Thirty years I raised him after his parents died,” she whispered. “Everything I had, I gave.”

“Mrs. Patterson,” I said carefully, “if you could take control back—would you?”

Her eyes sharpened, hope and terror in a teacup. “In a heartbeat.”

That night, wind rattled Sunset Manor’s windows and someone cried behind the thin wall and Eleanor swore into her pillow about the coffee. I lay awake and counted the beats between lightning and thunder. This place was full of women like me—smart, reduced. I wasn’t powerless. I’d just been acting like it hurt less.

Tomorrow, I told Richard, I start.

Three mornings later, I heard Lilia before I saw her—heels clicking down the hall like a metronome for entitlement. I tucked Marcus’s fresh documents under my pillow.

“Mom?” Blaine knocked, voice oiled. “Can we come in?”

I arranged my face in the way people expect old women’s faces to arrange. “Of course.”

Lilia’s nose wrinkled at the antiseptic. Cashmere collared her throat. Somebody’s money—mine—paid for it.

“How are you feeling?” Blaine asked, eyes scanning the room for loose diamonds.

“Oh, some days better than others.” I let my voice quaver. “The food isn’t very good.”

“We have a few questions,” Blaine said, taking the one chair. “Some inconsistencies in Dad’s paperwork.”

“What kind?” I blinked, slow as a lizard.

“We found references to accounts and assets that weren’t in the estate,” Lilia said, politeness fraying. “We need to know what Richard hid from us.”

Not from you, dear. From you.

“I don’t understand,” I said. “Your father handled all the financial matters.”

“Think, Mom,” Blaine said, that old tell at his jaw twitching. “Any mention of offshore accounts? Properties? Stocks in other companies?”

Desperation had started to kiss his sentences.

“There might be papers in your father’s study,” I said. “In the filing cabinet behind his desk. Investment statements. Legal language I never really understood.”

Lilia’s eyes glittered. “We’ll check.”

“Is there anything else you remember?” Blaine asked.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, and let my gaze drift like a woman who can’t hold a thought with both hands. “My memory…”

After they left, I gave them twenty minutes to get out of the parking lot. Then I called Marcus.

“How bad?” I asked.

“Worse than you thought,” he said. “Riverside’s gone. Johnson’s considering. Two others are ‘reviewing’. He’s bleeding cash. And—your daughter-in-law hired a PI. She’s sure you’re hiding money.”

“Of course she is,” I said. “Accelerate the timeline. How soon can you have the documents ready?”

“Friday,” he said. He hesitated. “Are you sure?”

I watched Mrs. Patterson fold her letter into a smaller shape as if shrinking paper could shrink disappointment. I thought about Eleanor’s eye roll at the bingo schedule. I remembered Lilia’s voice over my lilies.

“I’m sure,” I said.

By afternoon, Eleanor slapped the business section on our table. “Thought you should see.”

LOCAL MANUFACTURER FACES MAJOR LAYOFFS. The story used the phrase “new leadership” like a shrug. Hartwell Industries, family-owned. Contracts lost. “Adapting to market conditions.”

“That your boy?” Eleanor asked.

I nodded.

“Sounds like he’s in over his hair,” she said.

“What would you do,” I asked, “if you had the power to stop something terrible—but it would hurt someone you love?”

“Depends,” she said. “Sometimes the hurt is the medicine.”

That night, lightning crept closer. I didn’t flinch.

Friday, the phone woke the hallway.

“Emergency bankruptcy filing,” Marcus said. “This morning.”

“What triggered it?”

“Johnson walked,” he said. “He tried to push a twenty percent increase. They signed with a competitor. House is going on the market this afternoon.”

“My house,” I said, and tasted bile. I had signed it to Blaine in a flurry of grief. Trust is a luxury. I had mispriced it.

I called Blaine.

“Mom?” He sounded like a boy who’d finally noticed the dark.

“I heard about the company,” I said. “Are you all right?”

“Who told you?”

“It’s in the paper,” I said. “And we have eyes here.”

“It’s just strategic reorganization,” he said, condescension wrapped in panic. “You don’t understand business.”

“I understand your father built a company in thirty years and you’ve broken it in two months,” I said.

Silence.

“Are you selling my house?”

“We need capital,” he said. “It’s just sitting there. With your medical expenses—”

“My medical expenses are two prescriptions and a multivitamin, Blaine,” I said. “And the nursing home you chose.”

“That’s not—”

“Then why?”

He didn’t answer. He didn’t need to.

I hung up and stared at the television until all the commercials sounded like apologies.

“You’re thinking hard,” Eleanor said.

“I’m done thinking,” I said. “I’m starting.”

I called Marcus. “Schedule a shareholders’ meeting,” I said. “Thursday. Ten a.m.”

“For the bankruptcy?” he asked.

“For the weather,” I said. “I’m bringing a storm.”

Part II

I put on the navy dress I used to wear to quarterly reviews, the one that makes me look like a principal you don’t want to disappoint. Eleanor pinned my hair back so tight it could have filed a restraining order. “You look like you’re going to war,” she said.

“I am,” I said.

The taxi to Hartwell Industries felt like time travel. The building hadn’t changed: glass pretending transparency, steel pretending permanence. The receptionist looked new and worried. The conference room still smelled like coffee and men explaining things they’d learned from you.

Blaine sat at the head of the table in his father’s chair, papers spread like a spill he hoped would mop itself. Lilia at his elbow, manicured fingers tapping a rhythm I recognized from the day she told me to call her “Lilia” instead of “Mrs. Hartwell” because we were “family.”

“Mom?” Blaine said, confusion tripping annoyance. “What are you doing here?”

“This is a business meeting,” Lilia said, crisp. “Not a social call.”

I took my old seat—the one at the far end where wives sit while men pretend not to check for approval. Marcus came in behind me with a briefcase that could have held a smaller briefcase. He nodded, and the meeting began.

“Thank you all for coming,” Blaine said to the board, none of whom met his eyes. “As you know, we’re facing temporary headwinds—”

“I called this meeting,” I said, my voice steady. It cut like a seam ripper through cloth.

Blaine blinked. “Mom, you can’t—”

“I can,” I said. “Marcus?”

Marcus slid papers across polished wood. “For the record,” he said, “Mrs. Sloan Hartwell owns seventy-five percent of Hartwell Industries, Inc. She has held the controlling interest since incorporation in 1987.”

Silence has flavors. This one tasted like copper.

“That’s impossible,” Blaine said. “Dad left the company to me. I saw the will.”

“The will left you twenty-five percent and operational control,” Marcus said. “Ownership was structured to protect Mrs. Hartwell.”

Lilia’s face did a complicated thing—shock, calculation, fury. “You knew,” she whispered. “All this time.”

“I knew,” I said. “Just as I knew when you put me in a nursing home. Just as I knew when you listed my house.”

“Mom,” Blaine said, voice fraying. “If you owned the company—why didn’t you say anything? Why let me—”

“Destroy it?” I finished for him. “Because I wanted to see what kind of man you were without your father’s shadow. Because you said you’d take care of everything. Because sometimes the only way to teach a grown man consequences is to let him meet them.”

He looked like he might cry. For a second I saw the boy with a skinned knee, furious at the sidewalk for being itself.

“What do you want?” Lilia asked, regaining her edge. “Money? An apology? What will satisfy you?”

“This isn’t about satisfaction,” I said. “It’s about stewardship. Blaine, you’re removed from all operational roles. Effective immediately.”

“You can’t fire me,” he said, standing. “This is my inheritance.”

“This is my company,” I said. “Your inheritance was a chance to earn this chair.”

Marcus set a single sheet in front of me—clean, legal, cruel in the way necessary things are. I signed with a hand that didn’t shake.

“What about the bankruptcy?” Lilia demanded.

“Withdrawn by close of business,” I said. “I’m injecting capital. Payroll will run Friday. Vendors will be paid. We will call Johnson and Riverside and the others and remind them what reliability tastes like.”

“Mom,” Blaine said, softer now. “I can do better. I made mistakes, but—”

“This isn’t about your homework,” I said. “This is about men with mortgages you put at risk so your spreadsheets could feel brave. This is about forgetting that a company is a promise you make to people you will never meet. And it’s about your mother.” The room pressed in. “You put me away because it was convenient to believe I was a burden instead of a resource.”

He flinched. “I—”

“You will never speak to Mrs. Patterson or Eleanor or the women at Sunset Manor, but you made a choice that told them who they are allowed to be. You will live with that.”

He sat. He stared at his hands. I looked at the board—men who had let my son drive a truck he could not control because he had the right last name.

“I’m appointing Sarah Chen interim CEO,” I said. Sarah—plant manager for a decade, respected because her word is the kind machines obey—raised her eyebrows and then nodded once. “She will hire back what can be hired, salvage what can be salvaged, and build something that won’t scare so easily.”

“Mom,” Blaine said, breaking, “please.”

I loved him. That’s the part people don’t want to hear. I loved him when he was wrong. I loved him when he wasn’t mine to save.

“You may stay on as a consultant,” I said. “Entry-level pay. No direct reports. You will learn the plant. You will learn our customers’ children’s names. You will learn how long a pallet takes to move when the forklift is out for maintenance. If Sarah approves, you will stay. If she doesn’t, you’ll leave.”

He nodded too fast, then stopped, then nodded once—like a man making a promise to himself.

“Meeting adjourned,” I said. “We have calls to make.”

I left them in that room with the ghosts of their certainty. Outside, the air tasted like rain. The taxi driver asked if I wanted the radio on. “Not yet,” I said. “I want to hear the quiet.”

Back at Sunset Manor, Eleanor was waiting in the common room with a look that said, Tell me everything and start with the good part.

“How’d it go?” she asked.

“I fired my son,” I said.

“Good,” she said. “Coffee?”

We drank from styrofoam cups like contraband. Mrs. Patterson shuffled in with a smile I hadn’t seen before—a letter in her hand, a photo paper-clipped. “He’s coming,” she said, breathless. “My grandson. Sunday. He said he’s sorry.”

“Good,” I said.

That night, I called Marcus. “Buy the building on 9th and Maple,” I said. “The old apartments. We’re going to fix them up. Seniors only. Dignity optional but inevitable.”

“And the old warehouse on Cedar,” I added. “Community center. Art classes, clinics, free legal consultations on Thursdays. And I want a garden.”

“A garden,” he repeated, and I could hear the smile through the wire.

“My people need something to grow.”

On Monday I checked out of Sunset Manor. I left my key on the desk without a thank you because I had learned to reserve gratitude for those who earned it. I moved into a small ranch with windows that opened and a yard that wanted tomatoes. Eleanor brought coffee cake. Mrs. Patterson brought a tray of seedlings and an opinion about trellises.

At the plant, Sarah called with updates I could breathe to. “Riverside is taking our call,” she said. “Johnson will meet next week. I told our people there won’t be layoffs. I didn’t promise, but I told the truth.”

“Good,” I said. “Always the truth.”

By month’s end the bankruptcy petition was dust. By quarter’s end the bleeding had slowed. We were still hurt. We were not dead.

One morning, a realtor’s sign appeared in front of my old house: SOLD. I parked across the street and watched a young couple carry in a lamp and a box labeled “DISHES!!!” in a handwriting that believed in exclamation points. For a minute, sadness tried to sell me a timeshare. I didn’t buy. The house belonged to a different version of my life. I wished it well.

Blaine called three times over six months. The first, loud and full of lawyers. The second, bargaining. The third, quiet.

“Mom,” he said, voice scraped. “I got a job.” Not at Hartwell. Somewhere smaller. Somewhere without his last name on the side of a building. “Entry-level,” he said. “I make lists and I don’t mess them up.”

“Good,” I said. “Do your job. And then a little more.”

“Lilia filed the papers,” he said. “It’s done.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it in the way you mean it when everyone involved is suffering consequences they auditioned for.

“I… I don’t know if you can forgive me,” he said. “But I want to try to earn back the right to be your son.”

“We can have dinner,” I said. “We can see.”

He cried, just once. Not pretty. Honest.

After I hung up, I went outside and planted basil. The earth smelled like something that remembered how to forgive without forgetting.

Part III

We cut the ribbon with kitchen scissors because nobody could find the ceremonial ones, and I’ve learned that ceremony should never get in the way of getting a door open.

“Welcome to Harbor House,” I said, and the little crowd cheered the way people cheer when they recognize themselves in the thing you’ve built. The sign was simple—steel letters on reclaimed wood. The smell inside was new paint, fresh coffee, and dignity.

Eleanor stood next to me in a navy pantsuit that had survived two weddings and a tax audit. “You’re sure you want me to talk?” she asked.

“I’m sure,” I said, and stepped back as she rolled her walker to the front like a podium.

“My daughter told me I was a safety risk after one tumble,” she said into the microphone that wasn’t on. She laughed, tapped it, and it crackled itself awake. “She promised a ‘lovely facility’ and dropped me where the bingo cards were sticky. Today I picked up a key. Feels like a key to a life. Thank you, Sloan.” She squeezed my hand so hard my bones made it onto her side of the handshake. “For remembering we are people.”

Mrs. Patterson stood with a potted rosemary like a graduate clutching a diploma. “I’ve got soil waiting out back,” she whispered, eyes bright. “The garden plot with my name on it.” Behind her, a dozen new residents shuffled, grinned, blinked at the light, told themselves it was all right to believe this would be better.

We toured the apartments. Nothing grand—just clean floors, windows that opened without a maintenance request, kitchens where kettles would sound like home. The community room was painted the color of a summer pear and already housed a donated piano that someone had tuned for free because his mother once sang in a church where nobody had time to argue about pitch.

“Calendar’s posted,” I told the new crowd. “Painting on Mondays. ‘Know Your Benefits’ clinic on Tuesdays—legal consults, paperwork help, the kind of phone calls that take an hour if you make them alone and ten minutes if you have someone who knows the menu options. Wednesdays we have Ask-a-Mechanic, because half the women in this city have been told a transmission fluid reservoir is a myth. Thursdays are open mic. Fridays, tai chi or chair yoga, depending on your knees. Sundays the garden meets. Non-denominational, as long as you worship the weeds.”

Eleanor elbowed me. “You forgot Saturday.”

“Saturday is naps,” I said. “Mandatory.”

After the tours, Sarah Chen came by in steel-toed boots and a blazer, the new uniform that said we had no intention of forgetting where the money came from. The plant had sent over folding chairs, a cooler of ice, and a man named Luis with a grill and an apron that read “Bossy in the Best Way.”

“Riverside called,” Sarah murmured as we watched Mrs. Patterson teach a retired math teacher how to coax a basil plant out of its sulking. “They want a meeting. Johnson, too.”

“Good,” I said. “Book them. Here, if you can. Let them see where our profits go.”

We scheduled Riverside for Thursday afternoon in the community room, because if a company wants to know whether you’re serious, show them a room that smells like coffee and work. The owner—Mr. Hart, whose father had eaten bologna sandwiches with Richard on a loading dock back when “Industries” was still a hopeful plural—walked in with two younger executives whose shoes were too quiet.

“You brought me to a senior center,” he said, scanning the room like a man who was used to reading production lines. “That’s new.”

“It’s ours,” I said. “We built it because we owe our elders more than a cul-de-sac with a television.”

Sarah gestured to the mockup on the table—new production schedules, a five-point quality assurance protocol that didn’t require a miracle, a list of old names we’d called and who had said yes. “We messed up,” she said, clean. “We chased a margin and forgot the promise. We’re not going to do that again.”

Mr. Hart’s face softened at her use of “we.” He looked around the room once more and spotted Mrs. Chen at the piano, playing a song I recognized from the night Richard taught me to two-step, and then he nodded.

“Two conditions,” he said. “You hire back Tito and Marisol if they want it. And you agree to quarterly walk-throughs with me. Not a tour. A walk.”

“Done,” Sarah said. We shook hands and the air felt ten degrees warmer.

We were packing away the chairs when Lilia arrived in a dress that said she believed in summer even when the calendar had other ideas. She walked through the common room like she was choosing a table at a restaurant, eyes appraising, mouth careful.

“Sloan,” she said. No “Mom.” No kiss. “I see you’ve been busy.”

“You’re welcome to have a cookie,” I said, pointing to the tray Mrs. Patterson guarded like a bouncer.

She held up a manila envelope instead. “You’ve misappropriated funds.”

“Good afternoon,” I said, because manners are a blade if you hold them right. “Did you drive or float in on indignation?”

She ignored it, sliding documents onto the table between us. “We have bank statements indicating substantial transfers from Hartwell Industries accounts to shell companies you control.”

I didn’t look at the papers. People in a panic always hope you’ll chase. “Shell companies,” I said. “You mean Hartwell Community Ventures and Hartwell Housing LP. Both registered with the state, both audited, both established by the board—some of whom are standing right over there, enjoying Tito’s salsa.” I pointed at Ed from Accounts Payable, who waved with a chip.

“Those funds,” I continued, “came from my personal distributions and an allocation approved as part of a philanthropic budget your husband used to sign without reading.”

Lilia’s smile became the face makeup makes when it realizes it can’t keep up. “I’ll be filing an injunction,” she said. “You can’t spend the company’s money like it’s your purse.”

“I’m not,” I said. “I’m spending my money like it’s my word.”

Her eyes slid around the room, looking for a friendly face and finding none. “You think these people will save you in court?” she asked, voice lowering.

“I don’t need saving,” I said. “But they do. From women who confuse greed with good judgment.”

She stiffened. “This isn’t over.”

“I hope not,” I said. “I enjoy seeing you learn.”

She left, heels clicking a retreat. Eleanor appeared at my elbow with two plastic cups of lemonade. “She’s going to try to scare you,” she said.

“She already did,” I said, smiling. “Right into doing something.”

Blaine chose the most neutral restaurant in town—a diner carrying forty years of coffee and french fries in its walls. He was early. He was alone. He had the particular look of a man who knows the right side of a burr grinder and now uses his hands for something other than swiping.

“Mom,” he said, standing. He didn’t try to hug me. “Thank you for coming.”

“You picked a good place,” I said, sliding into the booth. “The pancakes here are honest.”

He laughed, surprised at himself for remembering how. “I come on Saturdays,” he said. “Before my shift.”

“How’s work?” I asked.

He lifted his palms, showed me two slivers of new callus like a catechism. “Good. Boring. Corrective.”

We talked without performing. He told me about the names of parts he had once thought he understood and now understood in the way people do who can smell when aluminum needs rest. He told me about the man who trained him, thirty years on the floor, and the way that man refused to let Blaine lift wrong even once.

“Sarah’s tough,” he said, meaning it as a compliment. “She told me to show up for the volunteer day at Harbor House. Said I needed to learn that production isn’t the only thing that counts.”

“She’s right,” I said.

He looked down at the menu and up at me. “I owe you an apology,” he said, words heavy as change. “Not the bargaining kind. The other kind.”

“Then say it,” I said. “And don’t dress it up.”

He inhaled like a man about to dive. “I treated you like a burden because it made my fear sound noble. I used grief as a credential. I sold your memories to pay my mistakes and I called it strategy. I put you away because I didn’t want to see what I was doing to Dad’s company. I am sorry.”

I took a sip of diner coffee and let the silence do its job.

“Thank you,” I said finally. “It’s a start.”

We ate pancakes that got cold while we handled something warmer. When the check came, he tried to grab it. I let him. He earned a small victory.

At the register, the waitress with a name tag that said BETTY leaned in. “I’m glad, honey,” she whispered. “The two of you. It was getting silly.”

Out in the parking lot, he walked me to my car. He didn’t ask for what wasn’t yet his to ask. “I’ll see you Saturday,” he said. “The garden. I’ll bring a shovel.”

“Bring four,” I said. “We’re ambitious.”

He grinned and I saw a boy with a frog in his pocket and a detention slip for arguing that the vending machine stole his quarter.

Saturday, the garden rose like a rumor then a crowd then a fact. Eleanor directed with the precision of a general whose army needed to drink water. Mrs. Patterson explained to a man with forearms like faith how peas prefer trellises that don’t insult them. Blaine showed up with four shovels and two pairs of work gloves, then surrendered both to women who would use them better.

Sarah arrived with a trunk full of seedlings. “I’m better with torque than thyme,” she said, “but I’ll try.”

By noon, we had lines of new green and lines on our faces the sun had left like an approving teacher. The grill warmed up again. Mr. Hart stopped by with a box of donuts and an offer—sponsorship for the community center’s “Ask-a-Mechanic” series. “We’ll send our best,” he said. “People who won’t mansplain gaskets.”

“Bless you,” Eleanor muttered.

As we sat on overturned buckets and plastic chairs, a car pulled to the curb and idled. Lilia. Dark glasses, lips like a closed door, a phone pressed to her ear as if talking to someone important could make her remain important.

She didn’t get out. She didn’t wave. Then the car rolled on.

“Good,” Eleanor said under her breath. “Let the sun set on that.”

“Or teach her where east is,” Mrs. Patterson replied, which made me love her even more.

The next week brought two things I didn’t expect: a letter from Sunset Manor’s new administrator and a box of Richard’s things I hadn’t known existed.

The letter was printed on the kind of paper that thinks dignity is a watermark. Effective immediately, it read, Sunset Manor will be undergoing ownership change and facility upgrades. We invite you to join our Resident Advisory Council. Your feedback catalyzed necessary reform. A small victory, maybe. Or the kind of apology institutions make when they realize somebody’s keeping receipts.

The box had been found in an off-site storage unit Lilia forgot to inventory—a banker’s box labeled in Richard’s hand: For Sloan. Inside: his slide rule; a Polaroid of Blaine at ten with grease on his nose and triumph in his eyes; a letter.

If you’re reading this, it began, it means the future arrived on time. You always say my handwriting looks like a train schedule. Maybe that’s right. Schedules kept our lights on. But promises kept us human.

I left the company the way I did because men with my last name don’t always deserve power, and women with yours too rarely get it. Use it how you want. If Blaine forgets who he is, remind him. If he remembers, forgive him. Don’t let anyone—especially family—convince you that love is an excuse for cowardice.

Plant tomatoes for me. They like to be talked to, the way you talk to a shy child. Tell them there’s time.

I sat on my porch steps with the letter in my lap while the dog from next door put his head on my knee like a punctuation mark. I read it twice. Then I went to the garden and told the tomatoes there was time.

By the end of the quarter, Hartwell Industries was no longer an obituary draft. Sarah presented numbers that didn’t apologize. “We’re smaller,” she said, “and smarter. We kept the people who held us together when we didn’t deserve it.”

At the senior center, the open mic turned into a tradition where Mrs. Chen played “Moon River” and the men from the plant sang two steps behind the beat and nobody minded. The legal clinic filled with people who had been taught to be afraid of official paper and left carrying organized folders and new spines.

Blaine showed up every Saturday with four shovels, then three, then two, then none, because he figured out we already had enough shovels and what we needed was someone to push a wheelbarrow and take orders from women who had been told not to give them.

He didn’t ask me to move home. He didn’t ask me to bless him. He showed up. He changed his oil. He called his mother on Wednesdays to tell her a story with no moral except that he was still learning.

One evening, after the sun had apologized for the afternoon by throwing gold on everything, I found Lilia sitting on the curb across the street from Harbor House. She wore less makeup than I’d ever seen on her face. She looked not younger. Not older. Newer.

“I can’t find a job,” she said as if the curb had suggested we air our humiliations.

“You can,” I said. “You just haven’t yet.”

“I was good at managing a house,” she said, defensive out of habit. “Fundraisers. Volunteers. Budgets.”

“Those are skills,” I said. “Bring a resume. We need someone to run programming here. It’s a real job. The money won’t impress your friends.”

She stared at the center. At the windows with the hand-lettered signs. At Mrs. Patterson laughing with a man whose laugh sounded like car doors closing. “You’d hire me?”

“I’d interview you,” I said. “The women will hire you.”

She stood, smoothing a dress that didn’t scream its brand. “I don’t know if I can stand all the… sincerity.”

“You stood me,” I said. “This will be easier.”

She almost smiled. Then she left without promising anything, which is the best way to leave.

On a Tuesday, Mr. Hart came to his walk-through. He wore shoes that scuffed honestly and asked questions that weren’t traps. We walked the floor—took in the symphony of machines and people behaving like a conversation. He looked at Sarah and nodded. He looked at me and didn’t say, “I told you so,” which is a kindness I remember.

When he left, Sarah leaned on the railing of the mezzanine. “We’re out of the emergency,” she said. “Now we have the rest of the work.”

“Good,” I said. “The rest is my favorite.”

She snorted. “You’re strange.”

“I’m old,” I said. “I’ve had time to practice.”

That night, I drove past my old house on accident and on purpose. In the front yard, a swing moved without a child because the breeze had ideas. The new owners had planted a maple that would, in twenty years, shadow the whole yard. I pictured a future I didn’t need to own. I wished it well, again, and meant it even more.

At home, I sat at the kitchen table with Richard’s letter, my pen, and a blank page. Not a ledger. A list. What I owed and what I didn’t. What I promised and what I refused. What I’d learned the hard way and the ways I never wanted anyone else to learn if I could help it.

At the top I wrote: Respect is not optional. Stewardship or bust. Consequences aren’t cruelty. And power is for building.

I underlined building twice.

Part IV

The envelope from Lilia arrived the way trouble always does—midweek, registered mail, with a return address that suggested she had paid extra to make the paper feel like a threat.

NOTICE OF TEMPORARY INJUNCTION REQUEST, the cover sheet read. Inside: allegations dressed as conclusions, spreadsheets printed in grayscale to look grave, a few screenshots taken out of context—as if you could pull a sentence from a ledger and make it confess.

Eleanor read over my shoulder, see-sawing her glasses down her nose. “She’s saying you misused corporate funds.”

“She’s saying she’s still the main character,” I said.

Marcus called within the hour. “She doesn’t have standing, and even if she did, the money trail is clean,” he said. “But we’ll go to the hearing. Friday morning.”

“Public?” I asked.

“Open court.”

I wore the same navy dress, not because I was superstitious but because I enjoy a uniform. The courthouse smelled like old paper and gum. Lilia arrived with a lawyer who had the kind of hair that’s been complimented into arrogance. Blaine came alone and sat in the back, hands on his knees, expression neutral in the way men’s faces get when they’re trying to give everyone else room to be wrong.

The judge was a woman with a blunt bob and a face that could curdle milk. She listened without interrupting, which is the most dangerous kind of listening.

Lilia’s lawyer stood to perform. “Your Honor, Mrs. Hartwell—Sloan—has diverted corporate assets to entities she controls, including a ‘Harbor House’ and a so-called ‘community center.’ These expenditures do not benefit shareholders. They are vanity projects. We seek an injunction to freeze all disbursements and a court-appointed manager.”

Marcus, who knows how to make the truth sound like a tune you’re embarrassed to realize you forgot, stood with a stack of tabs. “Your Honor, the entities are fully audited and board-approved. The funds in question are owner distributions from my client’s seventy-five-percent stake and a budget line approved for corporate philanthropy—consistent with Hartwell’s giving for thirty years. We’ve attached audits, minutes, and receipts. We also brought witnesses—”

“Cut to your best five pages,” the judge said without looking up. “I can read.”

A rustle behind us. I turned. The first three rows of benches had filled without me noticing: Mrs. Patterson in her Sunday sweater, Mrs. Chen with her piano teacher posture, the Ask-a-Mechanic crew in clean work shirts, Sarah in steel-toe boots tucked under slacks like a secret, Mr. Hart—oh, my—arms folded, watching as if he were measuring a board. Even the nurse from Sunset Manor. Eleanor elbowed me, eyes bright. “Looks like you brought your audits.”

Marcus continued, “We also note that Ms. Lilia Hartwell—petitioner’s former spouse—recently liquidated assets belonging to the marital estate, including the sale of Mrs. Hartwell’s former home. If this court is interested in the equitable distribution of assets, we can file—”

The judge held up a palm. “No one is interested in spinning up a second circus today.” She turned to Lilia’s counsel. “Mr… hair product.” A faint smile fluttered at the back of the room. “What’s your theory of harm?”

“Shareholder value,” he said promptly. “Diversion of funds.”

“Your client owns how much?” the judge asked.

He blinked. “She—well—none.”

“Ah,” the judge said. “So she is here as… what? Ex-wife? Concerned citizen?”

He shifted. “As a witness to mismanagement.”

The judge leaned forward, elbows on the bench. “Here’s my problem. You’re asking me to tell a seventy-five-percent owner she can’t spend her own distributions on audited, board-approved projects that—checking my notes—house seniors, provide legal clinics, and host something delightfully called ‘Ask-a-Mechanic.’” She flipped a page. “Meanwhile, the business has stabilized under… Ms. Chen. Contracts returning. Bankruptcy withdrawn.”

She dropped the file like a teacher setting down a textbook she knows better than the author. “Motion denied. And Ms. Hartwell—” Lilia looked up, surprised to be called that again. “If you file again without actual evidence of malfeasance, I’ll consider sanctions.”

Lilia stood quickly, gathering papers as if speed might translate to dignity. She didn’t look at me. Blaine did. His face said not victory. Relief.

Outside, the nurse from Sunset Manor intercepted me. “Mrs. Hartwell,” she said, and I realized I had never learned her name. “It’s Dina. We’ve started the Resident Advisory Council. Your letter helped. We’re renovating. New ownership. Better ratios. Would you—” She flushed, then continued, brave. “Would you sit on the advisory board? Just for a year. Help us fix what we let break.”

I thought about the nights I had fallen asleep listening to strangers cry because they believed they had no choices left. “Yes,” I said. “But I want Eleanor as chair.”

Eleanor, who had been eavesdropping with the shamelessness of a woman who has earned the right, snorted. “I accept.”

The reckoning would not be applause or punishments. It would be meetings and checklists and a bulletin board that finally told the truth.

The first advisory meeting at Sunset Manor took place in the same common room where Mrs. Chen had once played with a missing queen of hearts. The new administrator—late thirties, sleeves rolled, eyes honest enough to be a risk—stood with a clipboard and no illusions.

“We failed you,” she said. “No excuses. This is how we become worthy of your trust again.” She pointed to a whiteboard divided into SAFETY, FOOD, PROGRAMMING, STAFFING, FAMILY VISITS. Under each, bullets. Some small: Replace stained carpet. Some sharp: Enforce two-visitor policy for non-family to reduce scams. Some simple: Windows that open.

Mrs. Patterson raised her hand. “Stop promising visits you don’t intend to make,” she said, looking at the families, not management. “If you can’t come, call. If you can’t call, send a postcard. But don’t say Sunday and then be Monday and then be never.”

A few sons and daughters shifted in their chairs. Shame is a necessary vitamin in moderation.

Eleanor took the marker and drew a square. “Thermostats. Residents control their own. No more ‘building standard’ that’s a man in an office who likes it cold.”

The administrator wrote THERMOSTATS on the board in capital letters and underlined it twice. “Done.”

We set up an ombuds desk. We recruited volunteer dentists for a monthly clinic. We trained staff to say residents’ names before they took vitals, not after. We replaced the “activity” of watching television with a carpentry class where two retired women taught twenty-year-olds how to square a corner without arguing.

Two months later, Sunset Manor didn’t smell like surrender.

Blaine’s test came on a Thursday night, when trouble likes to pretend it’s a weekend.

He was on second shift at the small plant where he worked—four presses, six men, a supervisor who understood that yelling is often a substitute for planning. A rush order came in from a regional distributor who had realized too late that someone else’s “expedited” meant “we’ll think about it.”

“Run the old die,” the supervisor said. “We can make the spec if we push the tolerances.”

Blaine had learned a lot of new words. Tolerance was one of them. “The old die won’t hold alignment at this speed,” he said. “We’ll spend more time troubleshooting than running.”

“Then wedge it,” the supervisor said, impatient. “Shims. It’s one pallet. Go.”

Shimming a die is like bracing a drunk friend. It works until it doesn’t, and when it fails, everyone falls. Blaine looked at the line—at a kid named Mateo whose hands had never held anything more dangerous than a game controller until this year, at a woman named Rosa who was paying for a class out of pocket, at the machine that would do what it was told even if the instruction was unwise.

He called Sarah.

“Don’t wedge anything,” Sarah said without hello. “I’d rather call the customer and miss the pallet than visit a hospital.”

“It’s not our plant,” Blaine said. “I don’t have authority.”

“You have a phone,” Sarah said. “Call the customer and be the voice of the adults.”

Blaine hung up and called the number on the PO. The man on the other end began at volume. Blaine listened. Then he said one sentence my father taught me and I had forgotten: “We can deliver you a problem now or a solution tomorrow. Pick.”

Silence. “Tomorrow,” the man said, grudging. “You better mean it.”

Blaine slowed the line. He stayed late to help clean. He got yelled at. He didn’t yell back. The next day, Sarah sent two of our techs to help set the die properly. The pallet shipped. The regional distributor called Mr. Hart to complain and ended up thanking him for sending adults.

That night, Blaine showed up at Harbor House with a pizza and an apology for being late to shovel compost. Eleanor handed him a rake. “Adults are always late,” she said. “They come anyway.”

Mr. Hart called me a week later. “Your boy saved us from a workman’s comp claim,” he said. “And probably a lawsuit. He had the sentence you can’t teach.”

“Which one?” I asked.

“Pick,” Mr. Hart said. “He made the customer pick. That’s leadership.”

I didn’t cry. But I looked up, out of habit, as if Richard were on the ceiling holding a tape measure and making sure I noticed we were finally plumb.

Lilia’s interview happened on a Tuesday with enough humidity to make everyone reconsider their hair. She stood at the front of the community room in a navy sheath that had been expensive and was now simply fabric. We’d set up a panel—not a firing squad, but not a tea party: me; Eleanor; Mrs. Patterson; Sarah; and a young man named Jay from the legal clinic who had learned to make bureaucracy afraid of him.

“Tell us about a time you were wrong,” Eleanor began.

Lilia straightened. “I thought getting what I wanted made me strong,” she said. “It made me dependent.”

Mrs. Patterson: “This job pays less than your manicure budget used to. How will you handle that?”

“I learned to paint my own nails,” Lilia said. She lifted her hand, palm-out, nails short and plain. “Turns out my hands still work.”

Jay: “You will work for people who won’t like you. Some with reason. What’s your plan on day one?”

“Listen, then wash dishes,” Lilia said. “I don’t know this room yet.”

Sarah: “What’s programming to you?”

“Not babysitting,” Lilia said. “Agency. Skills. Joy. Paperwork help. Tai chi because balance matters. Open mic because stories fix things money can’t.”

I asked the last question. “If we say no, what will you do?”

She didn’t blink. “Ask why. Fix it. Try again somewhere else that needs fixing.”

We didn’t hire her on the spot. We made her wait 48 hours and brought her back to shadow two full days. She did wash dishes. She listened. She was too crisp with Mrs. Chen and apologized without asking for forgiveness. On Friday, we offered her the role: Program Coordinator, six-month probation, compensation modest, benefits better than expected.

She cried. Not pretty. Honest.

Her first project wasn’t a gala—no one needed another evening where rich people clinked and called it kindness. She started a Grandkids & Gears Saturday: grandkids bring broken things; retired mechanics teach them to fix them. The first week, they repaired two lamps, a toaster, three bicycles, and a little boy’s conviction that he couldn’t do hard things. Lilia sat on the floor next to a girl with pink barrettes and held the flashlight while the girl tightened a stubborn screw.

“Don’t strip it,” Lilia said softly. “Let it know you’re in charge and then be gentle.”

I stood in the doorway and watched a woman I had once called a storm learn to be a forecast you could live by.

The harvest festival was Lilia’s idea, Mrs. Patterson’s menu, and Eleanor’s schedule, which meant it ran on time and over budget in the way joy always does. We hung strings of lights and hauled out folding tables and asked Mr. Hart to borrow a portable stage which he delivered himself because he didn’t trust teenagers with a hitch.

The sign over the door of the community center read Maple & Lily, a name Mrs. Patterson insisted on because “we survived both.” We put Richard’s letter in a frame by the entrance—opened to the paragraph about power and building. People touched the glass on their way in the way some people touch mezuzahs: not superstition. Intention.

Blaine manned the grill with Luis, sweat on his forehead, a smile that didn’t apologize for being used. Sarah made a speech that was three sentences and all verb. Jay ran a table where he signed two seniors up for benefits they were eligible for ten years ago but never knew how to claim. Mrs. Chen played, and this time the queen of hearts showed up, right on beat.

Midway through the evening, the Sunset Manor van pulled up, and residents stepped out, shoes clean, hair combed, hope visible. Dina, the nurse, waved, and I could have sworn she stood an inch taller. The carpentry class presented a planter they built: cedar, straight as a sermon. We planted rosemary in it, for remembrance, and basil, for bravery, and tomatoes, because Richard told me to.

I took the mic not because I like them but because some rooms deserve a sentence you can hang the night on.

“Thank you for coming,” I said. “We built this with company profits and personal money and stubbornness. We didn’t do it because it made sense on a spreadsheet. We did it because promises aren’t promises unless somebody can see where they land.”

I looked at Blaine. “We made mistakes,” I said. “We learned. We will make more. We will learn again.”

I looked at Lilia, who was refilling water pitchers and not ducking the eye contact. “We’re not here to make a point,” I said. “We’re here to make a place.”

We unveiled a small plaque by the garden gate. POWER IS FOR BUILDING, it read. Underneath, smaller: Richard & Sloan. 1983–Forever. I pressed my palm to his name. The wood felt warm.

Later, when the tables had been folded and the mosquitoes made their case and the lights were quickening the dark, Blaine walked me to my car. He didn’t rush the way men rush to prove they aren’t uncomfortable. He matched my steps.

“Mom,” he said, “Mr. Hart offered me a job. Not at Hartwell. At his father’s old place. Night supervisor training. He said I had the sentence he likes.”

“Pick?” I said.

“Pick,” he said. “And ‘don’t wedge anything.’”

“What did you tell him?”

“I said yes,” he said. “But I told him I volunteer here on Saturdays.”

“Good,” I said.

He looked at the garden. At the planter box we built. “I’m proud of you,” he said. “Dad would be, too.”

“I know,” I said, because I finally did.

When I got home, the house breathed like a well-made bed. I set a kettle to boil and took Richard’s letter to the porch. I wrote him back with the old fountain pen, the one that still leaves a tiny blot when you pause because it wants you to keep your hand moving.

We planted tomatoes. I told them there’s time. Blaine learned to pick. Lilia learned to hold a flashlight. Sarah saved the company and taught me how to say numbers without apology. Sunset Manor opens its windows now. We named the center Maple & Lily. I used your line on the plaque. People touch it on their way in. You’d like that.

I kept my promise. I didn’t let anyone push me around. Thank you for leaving me the levers and the map. I used both. I am tired in the good way. The garden needs staking tomorrow. I have twine. Come by if you can. If you can’t, I’ll tell the tomatoes you sent your love.

The kettle sang. I made tea. I stood by the open window and listened to a city that had learned one more place to be kind.

In the yard, the rosemary reached over the path like a neighbor. The maple down the block pushed at the sky. Somewhere, a piano practiced the same four bars over and over until they finally sounded like a beginning that knew how to arrive.

Power is for building. So we built.

THE END

News

He Said ‘It’s Just Baby, You’ll Be Fine’ and Went Out With Mistress Next Morning His Boss Called… CH2

Part I The contractions began the way summer storms do—distant at first, a rumor in the sky—then suddenly right on…

His Wife Screamed: “Don’t You Dare lecture my kids”—But His Revenge Left Her Speechless… CH2

Part I: The smell of garlic and butter should have softened the night. The lasagna was still steaming in the…

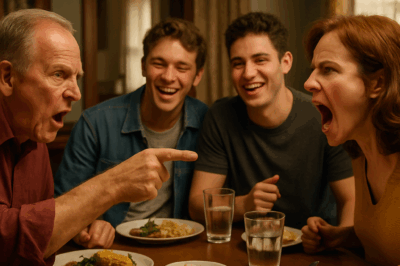

At Family Dinner She Said, “He Means Nothing” — Then Froze When I Put the Photos on the Table… CH2

Part I: The smell of roasted chicken and garlic bread had always meant comfort. For years it was the background…

He faked his disappearance just to play a trick on me, yet I flew to the US with his best friend… CH2

Part I The second month after my boyfriend “went missing,” I saw him. By then, the flyers with his photo…

MY WIFE ABANDONED ME AND OUR NEWLY BORN TO GO AWAY WITH HER LOVER BUT SHOWED UP LATER. NOW SHE… CH2

Part I The room smelled like antiseptic and formula, that sterile sorrow hospitals press into your clothes and send you…

My Sister Tried To Humiliate Me At The Will Reading – Then Froze When The Judge Revealed… CH2

Part I Two days. That’s all the notice I got. A stiff white envelope sat on my doormat in Atlanta,…

End of content

No more pages to load