Part I

June 3rd, 1944

Pearl Harbor

0600 hours

The sun had barely risen, its light sliding across the battered docks and steel-gray water of Pearl Harbor, when Admiral Chester W. Nimitz stepped into his headquarters. The building, once a quiet administrative space, now thrummed with the tension of a global war. The air carried the scent of coffee, sweat, and brine—a mixture that clung to every man stationed in the Pacific Fleet nerve center.

On the corner of his desk sat an envelope stamped with a red warning:

ULTRA — EYES ONLY — TOP SECRET

Nimitz picked it up without hesitation, though he knew that any message with that label meant something big—something terrible or something urgent.

The admiral broke the seal and read the decrypted intercept slowly, silently.

Halfway through, he stopped breathing.

He read it a second time.

Then a third.

Finally, he exhaled.

The Japanese Combined Fleet was concentrating near the Mariana Islands.

One location.

One moment.

One chance.

A decisive battle—the kind both sides had known was coming since 1942—was about to ignite in the Central Pacific.

For months, U.S. planners had speculated where the Japanese would make their stand. Some guessed the Carolines. Others, the Bonin Islands. A few believed Japan would hold its fleet in reserve indefinitely.

But Ultra—the silent, invisible weapon of codebreakers—had spoken.

The enemy was gathering at the Marianas.

Saipan.

Tinian.

Guam.

The very islands the United States planned to invade.

The islands that could put American long-range bombers within range of Tokyo itself.

Nimitz didn’t waste time.

He turned to his operations officer.

“Get the staff,” he said, voice low and calm. “We begin immediately.”

By 0615, the room was packed. Officers crowded around maps spread across a long oak table. Colored pushpins marked fleets, supply depots, submarine patrol routes, and known Japanese positions.

Rear Admiral Forrest P. Sherman studied the intercept over Nimitz’s shoulder.

“This is it,” he said under his breath. “The decisive fleet action.”

“Yes,” Nimitz said. “And the initiative is ours.”

But even having the enemy’s location wasn’t enough.

The real challenge lay elsewhere.

Nimitz tapped a finger on the map—first at Pearl Harbor, then at Majuro, then at Espiritu Santo, then Guadalcanal.

“Two hundred ships,” he said. “Scattered across half the Pacific.”

Carriers.

Battleships.

Cruisers.

Destroyers.

Tankers.

Transports.

Landing craft.

Every piece of the Pacific machine spread thin across thousands of miles of ocean.

Rear Admiral Charles “Soc” McMorris frowned deeply.

“To arrive at Saipan in time…” he calculated aloud, “…we need coordinated movement from four major anchorages.”

“And without radio transmission,” another officer added. “Not one signal.”

Everyone understood why.

The Japanese were masters of radio interception. One burst of communication—even encrypted—would reveal movement. And if the Japanese detected movement—

They’d scatter.

Reposition.

Guard the Marianas.

Possibly ambush the invasion fleet.

The entire Saipan operation would collapse before it began.

Nimitz folded his hands.

“We cannot fail.”

He looked around the room—at the faces of men who had survived Midway, Coral Sea, Guadalcanal, Tarawa.

“The Japanese plan to fight their decisive battle near Saipan,” he continued. “We will strike first. Quietly. Precisely. And with overwhelming force.”

A murmur moved through the room.

“For that,” Nimitz said, “we have seventy-two hours.”

Silence.

No one spoke.

Because everyone knew what that meant.

Seventy-two hours to coordinate:

200 ships

3,000 miles

Zero radio communications

Four different bases

One rendezvous point

One shot at victory

It was madness.

It was impossible.

It was Nimitz’s specialty.

The Pacific wasn’t like Europe.

In Europe, armies advanced along roads and railways, ate from supply depots, refueled from captured stockpiles, and reused enemy infrastructure.

In the Pacific, the ocean itself was the battlefield.

No roads.

No railways.

No infrastructure.

Every gallon of fuel, every shell, every part, every meal had to be transported by ship.

And the distances?

Pearl Harbor to the Marianas: 3,000 miles

New York to London: 3,000 miles

Same distance.

But vastly different conditions.

A single U.S. battleship consumed 8,000 gallons of fuel per hour at cruising speed.

A typical carrier task group—one carrier, four destroyers, two cruisers—burned 50,000 gallons per hour.

Task Force 58, the main U.S. strike force under Admiral Marc Mitscher, consisted of:

15 aircraft carriers

7 battleships

21 cruisers

69 destroyers

At cruising speed, they devoured 1.2 million gallons of fuel per day.

Just to reach Saipan from Majuro:

4.8 million gallons.

Not counting the battle.

Not counting the return trip.

Not counting emergencies.

The Japanese Navy faced similar issues—but they approached logistics differently.

Japanese logistics were:

centralized

slow

bureaucratic

inflexible

Every movement required approval from Combined Fleet Headquarters in Tokyo.

Every diversion required recalculation.

Every supply convoy needed weeks of advanced planning.

It was a system built for predictability.

Not speed.

Not improvisation.

Not a war controlled by radar, codebreakers, and opportunity.

Nimitz, on the other hand, was a submariner.

Submariners live and die by:

independence

foresight

initiative

self-sufficiency

They cannot call for help.

They cannot wait for permission.

They cannot rely on external support.

They must anticipate everything before they dive.

Nimitz brought this philosophy to the Pacific Fleet.

And on June 3rd, it was about to pay off.

This wasn’t something Nimitz improvised.

It wasn’t luck.

It wasn’t genius in the moment.

It was planning—years of it.

When he took command in December 1941, Pearl Harbor was in ruins. The battleship fleet was crippled. The Pacific theater was reeling.

But Nimitz didn’t dwell on the damage.

He built a system—a logistical masterpiece—that would support the most aggressive naval campaign in history.

He established:

forward fuel depots at Ulithi, Eniwetok, and Majuro

repair ships prepositioned across the Central Pacific

ammunition barges waiting at rendezvous points

supply vessels ready to move at a moment’s notice

He decentralized decision-making:

Task force commanders received mission objectives—not step-by-step instructions.

They were trusted to execute using their judgment.

Every commander carried sealed contingency orders:

Envelope A — if the Japanese move north

Envelope B — if they move south

Envelope C — if communications fail

Every rendezvous point across the Pacific had predetermined coordinates.

Every logistics vessel carried enough supplies for three full days of combat operations.

Every situation—every possibility—had been anticipated.

This was not improvisation.

This was a symphony.

A logistical symphony composed over two years.

And the Japanese had no idea the music was about to begin.

To execute the plan, Nimitz needed every major fleet component to start moving within the next 72 hours.

Not one could break radio silence.

Not one could slip up.

Not one could give away the plan.

At 0800 hours:

A PBY Catalina took off from Pearl Harbor carrying sealed orders for Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner at Guadalcanal.

Flight time: 6 hours.

At 1000 hours:

Another PBY departed for Espiritu Santo with orders for the logistics support group.

Flight time: 7 hours.

At 1200 hours:

A B-24 bomber left for “anywhere”—a classified base in the Pacific—carrying orders for the escort carrier group.

Flight time: 5 hours.

By evening, couriers were crossing thousands of miles of ocean and island chain.

Each envelope contained:

rendezvous coordinates

departure deadlines

fuel requirements

fallback options

contingency routes

But each commander had to calculate:

speed

fuel consumption

weather

loading times

mechanical readiness

formation sequencing

Turner at Guadalcanal immediately faced a crisis:

His transports needed 36 hours to finish loading supplies.

But they needed to depart in 48 hours.

At maximum speed, they could barely make the rendezvous on time.

He made a brutal decision:

Load only essential supplies. Ammunition and fuel.

Food will be resupplied at sea.

It shaved loading to 24 hours.

He departed 12 hours early.

At Espiritu Santo, another issue emerged:

The escort destroyers protecting the logistics group were undergoing boiler maintenance.

The commander, Captain Harold Stassen, made the call:

Sail with reduced speed.

Four boilers instead of six.

Maximum speed 25 knots.

Risky.

But necessary.

At “anywhere,” the escort carriers received orders at 1700.

They sailed at dawn the next day.

And Task Force 58?

They received their orders in a single coded message:

“Plan Orange. Rendezvous Charlie. Execute.”

That was all Mitscher needed.

He broke open his sealed orders.

At 1400 on June 3rd, he sailed.

The Pacific began to move.

Silent.

Coordinated.

Deadly.

For five days, the Pacific was alive with ships—sliding across the water like shadows, unseen, unheard.

200 ships

4 different origins

3,000 miles traveled

Zero radio transmissions

And not one crewman outside the command staff knew the full plan.

Afternoons brought heat so thick sailors felt it in their bones.

Nights brought stars so bright the ocean mirrored the sky.

Waves battered hulls.

Salt soaked decks.

Engines throbbed relentlessly.

Communications were restricted to:

signal lamps

hand flags

pre-arranged maneuvers

silence

The vastness of the Pacific swallowed them whole.

Destroyers cut white paths through rolling swells.

Carriers churned steel-blue water in their wake.

Tankers lumbered behind them like floating oil fields.

Every captain checked his charts hourly.

Every navigator triple-checked their headings.

Every commander carried the same fear:

One mistake could give everything away.

But none did.

Because Nimitz’s system was holding.

And on June 9th, they approached Rendezvous Charlie.

June 9th, 1944

0600 hours

200 miles east of Saipan

Rendezvous Charlie was nothing but empty ocean.

No island.

No beacon.

No landmark.

No navigational aid.

Just the coordinates in their sealed orders.

Task Force 58 arrived first.

Fifteen carriers appeared over the horizon like steel mountains. Destroyers fanned out around them. Battleships followed like armored giants.

At exactly 0800, Admiral Turner’s amphibious force arrived.

Seventy transports.

Thirty landing craft.

Twelve escort destroyers.

Exactly on time.

At 1000, Espiritu Santo’s logistics group appeared:

Twenty fuel tankers.

Fifteen ammunition ships.

Eight repair vessels.

Exactly on time.

At 1200, the escort carrier group arrived.

Eight escort carriers.

Sixteen destroyers.

Exactly on time.

Two hundred ships.

Four starting points.

Five days of silent transit.

A six-hour arrival window.

Zero communications.

It had worked.

Everything Nimitz built—every depot, every sealed order, every contingency—had aligned.

The Japanese had detected none of it.

While the American fleet massed east of Saipan—

The Japanese Combined Fleet still sat anchored at Tawi-Tawi.

Oil-slicked.

Sweltering.

Unknown.

Their reconnaissance aircraft flew over the Philippine Sea two days earlier and reported empty ocean.

Because five days earlier, the U.S. fleet had not yet arrived.

Ozawa, commanding the Japanese carriers, was still waiting for orders.

Still waiting for perfect timing.

Still waiting for direction from Tokyo.

On June 11th—three days late—the Japanese Combined Fleet finally received the command to sortie.

But the Americans were already in position.

Waiting.

Prepared.

Rested.

Supplied.

The Pacific trembled.

The decisive battle was about to begin.

And Nimitz knew:

The outcome had already been decided.

Not by gunfire.

Not by pilots.

Not by explosions.

But by logistics.

By the invisible work.

By the seventy-two hours before battle began.

By the system that only a submariner could have designed.

Part II

June 10th, 1944

Philippine Sea

0300 hours

The Pacific before dawn was a cathedral of stillness.

Black water.

Black sky.

The faint hum of engines beneath steel decks.

Task Force 58 had reached its holding point east of Saipan, and the ocean churned with life—sailors jogging between stations, mechanics tightening the last bolts on Hellcats and Avengers, cooks preparing coffee that tasted more like engine oil than food. Men stretched sore backs, washed salt from their clothes, and stared at the horizon where the sun would soon rise on the greatest naval concentration the Pacific had yet seen.

Mitscher stood on the flag bridge of the USS Lexington, binoculars pressed to his eyes.

Row after row of carriers lined the sea like floating cities.

Battleships loomed behind them—ancient giants reborn for a new kind of war.

Cruisers formed a ring of firepower.

Destroyers zigzagged in constant patrol.

Tankers loitered just behind, fat with fuel.

And—all around them—the quiet.

Not a single radio transmission.

Not a single message breaking the silence.

Every ship followed the sealed instructions that Nimitz had set in motion.

A decentralized system acting in perfect coordination.

Where other admirals would have micromanaged every movement, Nimitz had simply trusted:

If I have prepared correctly, the system will execute itself.

And it had.

The American Navy had arrived early.

It was the Japanese who were late.

Back in Hawaii, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz stood in front of the giant operations board. A dozen officers updated positions with grease pencils as fresh reports came in from long-range scouts and submarine patrols.

There was no excitement in Nimitz’s face.

No triumph.

No fear.

Just focus.

He studied the board with the mind of a man who had rehearsed this scenario a hundred times.

“Any Japanese carrier sightings?” Nimitz asked.

“None, sir. Submarines report heavy traffic at Tawi-Tawi but no movement east.”

Nimitz nodded. “They’ll come. Ozawa has no choice.”

Fleet Intelligence Officer Eddie Layton stepped beside him.

“Sir,” Layton said, “if they sortie today, they’ll still be three days behind your schedule.”

“Exactly,” Nimitz said.

His eyes narrowed.

That was the trap.

Not a trap of ships.

Not a trap of planes.

A trap of timing.

If Task Force 58 arrived first—

They could refuel

They could rest

They could rehearse

They could prepare for every Japanese tactic

Ozawa’s fleet, when it finally arrived, would be exhausted from constant refueling, frantic repositioning, and long days spent avoiding American submarine patrols.

Nimitz folded his hands behind his back.

“Ozawa isn’t fighting us,” he said. “He’s fighting the clock.”

June 11th, 1944

Tawi-Tawi Naval Base

0630 hours

Admiral Ozawa Jisaburō received the order he’d been waiting for:

SORTIE IMMEDIATELY TO THE MARIANAS.

Three days too late.

Three days behind the silent American armada already in position.

He stepped onto the deck of his flagship, the Taihō, and looked across the anchorage.

Pilots scrambled aboard aircraft.

Fuel lines hissed into warships.

Destroyers rushed to form screens.

It should have been impressive.

It should have looked powerful.

But it didn’t.

Everything felt strained.

Forced.

Rushed.

Japanese logistics had never recovered from the American submarine campaign.

Fuel shortages crippled every movement.

Aircraft fuel was a luxury.

Every sortie, every patrol, every maneuver drained resources Tokyo could barely spare.

Ozawa knew this.

He also knew what the Combined Fleet Director in Tokyo expected:

Victory.

A decisive battle.

A victory that would halt the American advance.

A victory that would save Japan from an invasion of the homeland.

But the reality in front of him was stark.

His fleet wasn’t ready.

His pilots were exhausted.

His fuel reserves were low.

His destroyers were stretched thin.

The centralized Japanese planning system suffocated his ability to adapt.

Every move had to be approved.

Every modification delayed.

Every request second-guessed.

They were fighting an enemy who moved like water through rock.

Flexible.

Fast.

Fluid.

“Sir,” his chief of staff said nervously, “we have reports of increased submarine activity.”

Of course there were submarines.

American submarines lurked along every likely approach to the Marianas.

The moment the Combined Fleet left port, they would be shadowed.

Ozawa placed his cap under his arm and stared east.

He felt something he had never felt before:

They’re ahead of us.

June 12th, 1944

Philippine Sea

0700 hours

Rendezvous Charlie was no longer empty ocean.

It was a machine.

A living, breathing organism of steel and men.

Refueling lines stretched across the water.

Destroyers zigzagged continuously.

Aircraft were lifted on deck elevators.

Ordnance crews loaded bombs into neat rows.

Deck crews painted stripes on flight decks for night recovery practice.

Everything was precise.

Everything was rehearsed.

Everything was calm.

Because Nimitz had engineered it that way.

On board the USS Enterprise, Lieutenant Jack “Thunder” McGraw sipped coffee on the deck catwalk. He was twenty-three, from Kansas, and had already fought at Truk and Kwajalein.

His squadron had been resting for the past five days.

Resting.

Not launching desperate patrols.

Not scrambling at dawn.

Not flying combat air patrols until their vision blurred.

“Feels like the quiet before a storm,” Jack muttered.

Beside him, Lieutenant Ted Hanley grinned.

“Mitscher’s giving us the easiest battle of the war,” he said. “Let the Japanese come to us. We’ll just swat ‘em out of the sky.”

Jack didn’t smile.

“It’s not that simple,” he said. “They’re not stupid. They’ll come in waves.”

“Sure,” Ted said. “And we’ll chew through every one. Turkey shoot.”

Jack shook his head.

He didn’t know it yet, but he was right—and wrong.

The battle that was coming would enter U.S. Navy history as “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.”

But not because of American pilot skill.

Because of logistics.

Because of preparation.

Because of the system Nimitz had built.

And because the Japanese were already three days behind.

June 13th, 1944

Pearl Harbor

1100 hours

Nimitz stood alone in his office, looking at a single sheet of paper.

A radio message.

Four words:

“Proceed as planned. Nimitz.”

It was dangerous.

Radio silence had been perfect until now.

But Mitscher needed confirmation that the Japanese had taken the bait—that the decisive battle was imminent.

Nimitz had weighed the risk.

Considered the necessity.

Calculated the odds.

He sent the message.

A single, tightly-beamed transmission.

Encrypted.

Directed.

Buried in ocean static.

Five seconds long.

The Japanese didn’t catch it.

But Mitscher did.

And the fleet opened Envelope C—confirmation of the enemy fleet’s movement.

June 14th, 1944

Philippine Sea

Dawn

American submarines had been positioned like chess pieces for weeks.

The USS Flying Fish was the first to make contact.

At 0330, its sonar picked up a distant rumble.

Moments later, a shadow appeared against the faint horizon.

A carrier.

Japanese.

Commander Robert Risser steadied his periscope.

“Contact bearing 082. Large fleet. Carriers, cruisers, destroyers. Heading northeast.”

He scribbled the details.

Then prepared the message.

Not by radio.

By prearranged code drops to other subs.

The information flowed slowly—deliberately—through the submarine picket line.

Each sub tagged the Japanese fleet, passing the data westward like a relay team.

By midday, Mitscher had the full picture.

Ozawa was coming.

Late.

Tired.

Low on fuel.

But coming.

June 18th, 1944

Philippine Sea

0500 hours

The day before the battle dawned quiet.

Flat seas.

Clear skies.

Visibility for miles.

Perfect for naval aviation.

Perfect for radar detection.

Perfect for an ambush.

But that wasn’t why Nimitz had chosen the Philippine Sea.

It was because it neutralized everything Japan needed to win.

Japanese Zero fighters needed close-range combat.

The Philippine Sea offered long-range radar and layered defenses.

Japanese pilots needed surprise.

Nimitz had already taken that away.

Japanese carriers needed calm seas to recover planes.

They would get storms within 48 hours.

Japanese fuel reserves were thin.

They were now dangerously low.

Everything the Japanese needed—

Nimitz had denied.

Everything the Americans needed—

Nimitz had supplied.

June 19th, 1944

Philippine Sea

1000 hours

“Bogie swarm inbound!”

The radar operator’s shout echoed in CIC (Combat Information Center) aboard the USS Bunker Hill.

Green blips crowded the screen.

Dozens.

Then scores.

Then hundreds.

The Japanese had launched their first wave—over 70 aircraft.

Then a second.

Then a third.

By noon, Ozawa had thrown 373 aircraft at Task Force 58.

He expected to overwhelm the Americans.

He expected dogfights.

He expected chaos.

Instead—

He got calm.

Jack McGraw tightened his harness in his F6F Hellcat.

“Thunder Flight, launch!”

Engines roared.

The deck surged beneath him.

He was airborne in seconds.

Altitude: 5,000 feet

Climbing: fast

Radar vectors: perfect

“Thunder, this is control,” the radio crackled. “Bandits bearing 085, angels fifteen. You are cleared to intercept.”

“Roger,” Jack said.

Below him, the Pacific stretched in every direction.

Ahead, the sky darkened with enemy fighters.

“Jesus,” his wingman whispered. “It’s like a swarm of hornets.”

Jack grinned grimly.

“No,” he said. “It’s like a slaughterhouse.”

Because everything the Americans had—

Combat air patrol rotations

Radar

Fuel

Rest

Perfect timing

Perfect planning

Perfect formation discipline

—Japan did not.

The Japanese pilots were exhausted.

Undertrained.

Flying long distances.

Desperate.

The Americans were not.

And the sky would soon prove it.

Jack dove.

Guns roared.

The Pacific exploded in fire.

The first wave of the Turkey Shoot had begun.

And it would only get worse.

For Japan.

Part III

June 19th, 1944

Philippine Sea

1020 hours

The first Japanese wave hit like a storm—but died like a spark.

Jack “Thunder” McGraw rolled his Hellcat into a steep dive, his engine screaming against the wind. The horizon tilted. The blue of the Pacific became a spinning disc of sunlit water and contrails.

The enemy formation was ahead—dozens of A6M Zeroes and D4Y dive bombers.

Jack steadied his sights.

Fired.

A Japanese bomber blossomed into flame, spiraling into the sea below.

The radio erupted with shouts:

“Angel 15, bandits scattering!”

“Scratch one!”

“Two on your tail, break! BREAK!”

“Christ, they’re coming apart!”

Mitscher’s plan was unfolding flawlessly.

Hellcats swarmed the sky in layered formations, directed by radar operators who tracked every blip of incoming aircraft. American pilots dove with the sun behind them, gunning down bombers before they ever reached attack altitude.

The Japanese had expected dogfights.

What they got instead was radar-driven execution.

Jack squeezed the trigger again. His tracers lanced into another bomber’s fuselage. Smoke erupted from the cockpit. A body tumbled out.

Jack didn’t watch it fall.

“Thunder Leader, this is Control! New group of bogies—bearing zero-eight-zero, angels twenty!”

Jack switched direction immediately.

His wingman panted into the radio.

“Where are they all coming from?”

Jack already knew the answer.

“They’re throwing everything they’ve got.”

What Japanese pilots didn’t know as they streaked toward the American fleet:

They were already defeated.

It had nothing to do with skill.

Or bravery.

Or aircraft quality.

It came down to exhaustion.

For five days, Japanese pilots had flown long patrols while their carriers refueled at sea. Some had slept only two hours a night. Others were assigned to combat patrols with barely time to eat.

And they were launching from farther away.

Task Force 58 had chosen its position to force the Japanese to fly longer distances just to attack.

That meant:

Less fuel

Fewer bombs carried

Weaker combat endurance

No margin for error

No ability to return if damaged

A Zero with a half-empty tank was already a dead plane.

Rear Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa didn’t know it, but his carriers had become floating traps.

He launched strike after strike.

And strike after strike evaporated.

1100 hours

USS Lexington

Flag Bridge

Mitscher stood silently, watching dots vanish from the radar screen.

Each blip represented an enemy plane.

Each disappearing blip represented another aircraft destroyed.

But his expression didn’t shift.

He didn’t celebrate.

He didn’t gloat.

He simply evaluated.

“Sir,” his operations officer said, “fighter direction reports over 100 kills already.”

Mitscher nodded.

“Maintain CAP rotation.”

“Yes sir.”

One of Mitscher’s aides murmured under his breath:

“This isn’t a battle… it’s slaughter.”

Mitscher’s gaze remained fixed ahead.

“No,” he said quietly. “This is preparation.”

The real slaughter—he knew—had not begun.

Not yet.

Meanwhile, aboard the Japanese carrier Shōkaku—

The weather was turning into hell.

Smoke from battle deck accidents curled into the sky. Pilots stumbled toward the launch positions, some clutching maps, others shaking from exhaustion. Flight deck crew scrambled to clear bomb carts from the runway.

“Launch the next wave!” the flight deck officer shouted.

“But sir—we need to refuel!”

“There is no time! Launch!”

A Zero attempted to take off, veered left, and smashed into the deck barrier. Flames roared upward. Fire crews rushed forward.

Another pilot vomited on the deck.

Fuel spilled.

Bombs sat unsecured.

Fatigue infected every movement.

They weren’t fighting the Americans.

They were fighting themselves.

1130 hours

Philippine Sea

14,000 feet

The second wave approached Task Force 58.

It was their largest—over 100 aircraft.

But as they neared, they encountered the American fighter screen.

It shredded them.

Radar-guided, organized, layered patrols attacked the Japanese formation from above, below, and both flanks.

Jack and his wingman Ted dove through a cluster of Japanese fighters. Tracers lit the sky.

“Thunder Two—break left!”

Ted rolled hard. A Zero clipped his tail.

“Damn it!” Ted yelped. “I’m hit! Oil pressure’s dropping!”

“Stay with it!” Jack shouted.

Ted leveled off, trailing smoke.

Below them, bombers that slipped through the upper screen encountered anti-aircraft fire from dozens of U.S. destroyers and cruisers.

Walls of flak exploded in synchronized bursts.

Japanese bombers flew straight into them.

They died by the dozen.

It was mechanical.

Predictable.

Inevitable.

“Where the hell are their fighter escorts?” Ted groaned.

Jack scanned the sky.

He didn’t see fighter escorts.

He saw Japanese pilots climbing too slowly, turning too wide, flying too rigidly.

Flying like they were out of fuel already.

Flying like they were out of time.

“Thunder Leader,” the radio cracked, “enemy bomber formation broken. Scraps only. They’re not organized.”

Jack exhaled.

He didn’t feel victory.

He felt… pity.

1200–1400 hours

All across the Philippine Sea

Wave after wave came.

Wave after wave died.

The Americans shot down:

30 planes

then 60

then 150

then 200

then 250

then 300+

Pilots later described it as shooting training targets.

Hellcats tore through Japanese bombers like wolves tearing into sheep.

AA guns finished the survivors.

By mid-afternoon, Japanese carrier decks were littered with burning wreckage. Flight crews cried openly. Pilots who returned landed with empty tanks, shaking hands, and bullet holes in every surface of their planes.

Admiral Ozawa watched from the bridge of Taihō.

He couldn’t understand what was happening.

“We trained for this,” he whispered. “We prepared. We gathered our entire fleet… how can we be losing so quickly?”

His staff offered no answers.

Because they all knew the truth.

They hadn’t trained for this.

Japan’s veteran pilots had died in earlier battles.

Their replacements had half the training.

Their carriers lacked radar.

Their logistics chain was collapsing.

Their fuel quality had deteriorated.

Their aircraft maintenance was rushed and sloppy.

Their fleet had been at sea too long.

Nimitz had designed this outcome.

Ozawa was living it.

Back aboard the Lexington, Mitscher studied the battle progression without emotion.

His officers whispered excitedly:

“Sir, the Japanese air arm is finished!”

“They’ve lost hundreds!”

“They can’t recover from this!”

Mitscher didn’t smile.

He turned to Captain Arleigh Burke, one of his most trusted officers.

“Arleigh,” he said, “we’ll finish them tomorrow.”

Burke nodded.

The decisive blow had been delivered.

But the killing blow was still to come.

Tomorrow, American planes would strike the Japanese carriers themselves.

Today had been about eliminating their air arm.

Tomorrow would be about sinking their ships.

1600 hours

Aboard Japanese carrier Hiyō

Ozawa received his first accurate report of the day.

“Sir,” an officer said quietly, “we estimate that less than fifty of the 373 aircraft we launched this morning have returned.”

Ozawa stared at him.

“That’s impossible.”

“It… it is accurate, sir.”

Ozawa’s knees weakened.

“That means—”

“Yes, sir,” the officer whispered. “We have no air wing left.”

A carrier without planes was nothing but a large, vulnerable target.

Back at Task Force 58:

Dozens of returning American aircraft ran out of fuel.

Jack himself landed with less than three gallons in his tank.

But every pilot who ditched saw something surreal:

Destroyers, lit up like Christmas trees, scanning the darkness.

Searchlights.

Deck lamps.

Signal lanterns.

Every light blazing.

In the middle of a warzone.

Destroyers dove toward splashes in the water.

Rescuing every pilot they could find.

A few pilots swam for minutes.

Some for hours.

But they were found.

Mitscher had ordered:

“LIGHT UP THE FLEET.”

It was unheard of.

Insane.

A beacon for enemy submarines.

But it worked.

And Nimitz had prepared for it:

American submarines formed a barrier behind the fleet.

Any Japanese submarine approaching would be intercepted long before reaching the illuminated carriers.

Every pilot returned alive.

Except for a handful lost to the sea.

By nightfall on June 19th:

Japan had lost:

343 aircraft shot down

Several more ditched

Many planes unable to return

Their most experienced pilots

Their ability to contest the sky

The U.S. lost:

130 aircraft (mostly fuel loss)

Nearly every pilot recovered

Zero carriers damaged

Zero ships hit

It wasn’t a battle.

It was a collapse.

Tomorrow would be the coup de grâce.

And Nimitz knew:

The Marianas were already won.

Part IV

June 20th, 1944

Philippine Sea

0410 hours

Before dawn, the Pacific was a mirror—still, dark, holding its breath.

But the men aboard Task Force 58 did not sleep.

Mechanics rolled torpedoes into place.

Ordnance crews lifted 500-pound bombs.

Pilots strapped themselves into cockpits, faces lit by red deck lamps.

Radar operators monitored the screen for the slightest flicker.

This day was different.

June 19th had shattered Japan’s air arm.

But June 20th?

June 20th would shatter their fleet.

On the flagship Lexington, Admiral Marc Mitscher stood on the flag bridge, his jaw tense. He had not celebrated yesterday’s victory. He had barely rested.

Today, he would make certain the Japanese Navy never recovered.

Captain Arleigh Burke approached.

“Sir,” Burke said softly, “scout planes report scattered contacts. Not conclusive yet, but… we’re picking up enemy radar shadows.”

Mitscher nodded. “Ozawa is running.”

Burke’s arms folded. “Sir… permission to pursue?”

Mitscher didn’t answer yet.

He looked west—toward the fading night.

Toward a fleet still out of reach.

And he remembered Nimitz’s words:

“The decisive blow will be yours to strike.”

Just after sunrise, the first blood of June 20th did not come from Mitscher’s carriers.

It came from beneath the waves.

The USS Albacore, commanded by Lieutenant Commander James W. Blanchard, had been shadowing the Japanese fleet for hours.

When dawn broke, he saw it:

A silhouette.

Long.

Massive.

Unmistakable.

The Japanese supercarrier Taihō.

Brand new.

Flagship of Ozawa’s fleet.

The pride of the Japanese Navy.

Blanchard knew he had seconds.

“TAKE THE SHOT!” his XO urged.

“Flood tubes one through six!” Blanchard shouted.

A tense silence fell as the firing solution tightened.

“FIRE!”

Torpedoes streaked into the blue.

Japanese lookouts spotted the wakes too late.

One torpedo found its mark.

A single explosion.

A single hole.

A single mistake on the Japanese crew’s part—

They sealed the ventilation system incorrectly.

Fumes filled the ship.

And hours later—

A spark ignited the vapors.

The Taihō exploded in a fireball so massive it could be seen twenty miles away.

Ozawa survived.

His flagship did not.

Later that morning, the USS Cavalla made contact with another large Japanese vessel being screened by cruisers.

Commander Herman Kossler adjusted the periscope.

He froze.

“Good God,” he whispered. “That’s the Shōkaku.”

The Shōkaku—veteran of Pearl Harbor, Coral Sea, and other major Japanese operations—had survived years of war.

Until now.

“FIRE!”

Torpedoes streaked through the depths.

Three struck home.

The Shōkaku erupted into flames.

Ammunition detonated.

Planes burned on deck.

The ship rolled starboard.

Moments later, a final blast split her in half.

She sank beneath the sea that had carried her since 1939.

Two Japanese fleet carriers—gone before noon.

The Pacific roared.

1400 hours

USS Lexington

Despite the submarine victories, Mitscher’s primary goal remained:

Destroy the Japanese fleet.

Finish what the subs started.

But the Japanese fleet was far—dangerously far.

“How far?” Mitscher asked.

Burke studied the latest report. “Three hundred and thirty miles, sir.”

Mitscher exhaled.

That distance was at the edge of American aircraft range.

A strike that far meant:

Barely enough fuel to reach the target

Even less fuel to return

A real possibility dozens of pilots would ditch in the dark

Burke hesitated. “Sir, we might not get them.”

“We’ll get them,” Mitscher said.

“But our planes—”

“If we don’t attack today,” Mitscher said, “we might lose them forever.”

Burke swallowed.

This was the moment.

Mitscher stepped toward the loudspeaker console.

His hand hovered.

Then—

He pressed the button.

“All carriers—launch everything.

Strike the enemy fleet.

This is a FULL STRIKE.”

Officers froze.

A full strike meant committing every aircraft they had.

No reserve.

No backup.

No second chance.

Burke whispered, “God help our boys…”

At 1600 hours, the decks came alive.

Dozens of TBM Avengers lined the flight decks, torpedoes slung beneath them.

F6F Hellcats and SB2C Helldivers revved engines.

Fuel crews gave thumbs up.

Deckmasters waved flags.

Then—

one signal:

“GO!”

Engines roared.

Propellers blurred.

The carriers trembled under the weight of their own power.

One by one:

Avenger

Hellcat

Helldiver

—all leapt into the sky.

Then ten.

Then thirty.

Then fifty.

Then a hundred.

Then two hundred.

Then more.

The entire horizon filled with aircraft.

Ted Hanley slapped Jack McGraw on the shoulder as they waited to launch.

“You ready to finish this war, Thunder?”

Jack managed a tight smile.

“Let’s make sure we make it home.”

They took off minutes later.

And behind them, Mitscher watched every plane disappear into the blue distance.

He felt the weight of every one of their lives.

This was the gamble of his career.

For two hours, the American strike force flew over an empty ocean.

Fuel gauges ticked downward.

Pilots clenched teeth.

At 1830 hours, just before turning back, they saw something.

Smoke pillars.

Wakes.

The silhouettes of ships.

Ted whistled. “Holy hell… it’s the whole Japanese fleet.”

Jack’s heart pounded.

They were within range.

Just barely.

“Thunder Leader to all aircraft,” he said. “We found them.”

The Japanese fleet had been running all afternoon.

Ozawa’s carriers were scattered.

Destroyers zigzagged frantically.

Cruisers fired anti-aircraft bursts into the sky.

But it wasn’t enough.

American dive bombers dove almost vertically.

Bombs screamed downward.

The Hiyō was hit first—torpedoes cracking her hull.

Flames erupted across her flight deck.

She sank in minutes.

Then the Zuikaku—the sole survivor of Pearl Harbor’s strike force.

Helldivers spiraled toward her deck.

Two bombs hit midships.

A torpedo struck below the waterline.

Smoke billowed from her hangars.

She listed heavily.

Jack strafed a cruiser, firing bursts along its deck.

Explosions erupted.

Japanese Zeroes attempted to intercept.

Ted shot one out of the sky.

Another crashed into the water.

The Japanese defense was valiant—

but overwhelmed.

Too many planes lost.

Too many pilots inexperienced.

Too much fuel gone.

Too many ships damaged.

The Americans had air superiority.

Complete.

Total.

Final.

By sunset, two more Japanese carriers were burning.

Ozawa watched from his last functioning carrier.

His fleet—

the pride of Japan—

was dying.

The sun dipped below the horizon.

Jack’s fuel gauge was dangerously low.

Ted’s voice crackled.

“Thunder Leader… I’m at fumes.”

Jack nodded grimly.

They all were.

Everyone was.

Mitscher had predicted this.

The American pilots didn’t have enough fuel to return.

Not in darkness.

Not across hundreds of miles.

Not scattered and low on radio coordination.

The strike had succeeded—

but now every pilot faced the same question:

Can we even get home?

2030 hours

Aboard the USS Lexington

Night had fallen.

The sea was black.

American pilots were now flying blindly over a pitch-dark Pacific, most nearly out of fuel.

Mitscher looked at Burke.

“If we don’t do something,” Burke said quietly, “we’ll lose hundreds of pilots in the water.”

Mitscher nodded once.

Decision made.

He stepped to the intercom.

“Attention, all ships,” he said.

“All ships…

TURN ON YOUR LIGHTS.

I say again—TURN ON YOUR LIGHTS.”

Burke froze.

It was the most reckless order any admiral had uttered in the Pacific War.

Running lights.

Spotlights.

Searchlights.

Deck lights.

Everything lit.

Every ship became a beacon.

A glowing target for any enemy submarine.

Burke whispered:

“This… this could get us sunk.”

“No,” Mitscher said. “This will get our boys home.”

And like constellations rising from the sea—

Task Force 58 lit up.

Hundreds of lights.

Miles of illumination.

A shining highway through the darkness.

Jack saw it first.

A faint glow on the horizon.

Then another.

Then a hundred.

Then the entire horizon lit with artificial daylight.

Ted gasped. “Holy—are those… our ships?”

Jack laughed—half disbelief, half relief, half hysteria.

“They’re guiding us in.”

As their engines sputtered, one by one, American pilots navigated toward the light.

Carrier decks were crowded.

Pilots were told to land wherever they could:

Any carrier.

Any deck.

Any ship with enough flat surface to catch a plane.

Dozens ran out of fuel in the final minutes.

Some ditched near destroyers.

Some landed on battleships.

Some floated until searchlights found them.

Jack landed on the Essex.

Ted ditched near a destroyer and was fished out within minutes.

By midnight—

most were home.

Mitscher had saved their lives with one act of audacity.

Nimitz’s system—planning for everything—had ensured rescue ships were positioned perfectly.

By dawn on June 21st, the Pacific was eerily quiet.

The Japanese Combined Fleet had fled.

Their losses were catastrophic:

5 carriers sunk

600 aircraft destroyed

Hundreds of elite pilots killed

Fuel reserves depleted

Operational capacity broken

The U.S. losses were minimal:

~130 aircraft (mostly fuel-related)

Nearly every pilot rescued

No major ship losses

The Japanese fleet was no longer a fighting force.

It was a ghost.

The decisive battle Japan had prepared for since 1942—

had ended in two days.

Decisive.

Total.

Final.

Because of logistics.

Because of preparation.

Because of Nimitz.

Because of seventy-two hours of perfect coordination.

Because of an admiral who understood that wars are won by systems, not speeches.

Part V

June 21st, 1944

Philippine Sea

0600 hours

Dawn crept over the horizon gently—golden light spilling across a calm ocean that only hours earlier had been filled with explosions, fireballs, and the sinking remnants of Japan’s pride.

Aboard the Lexington, Admiral Marc Mitscher stood at the rail.

His posture was straight.

His uniform immaculate.

His expression unreadable.

Around him, the sea stretched endlessly.

No enemy aircraft.

No roaring engines.

No thunder of naval guns.

Only silence.

The kind of silence that follows a storm so violent it reshapes the world.

Behind Mitscher, Captain Arleigh Burke approached quietly.

“Sir,” Burke said, “the final reports are in.”

Mitscher didn’t turn.

He only said:

“Read them.”

Burke unfolded a clipboard.

“Submarines confirm three Japanese carriers sunk.

Strike pilots report heavy damage to two more.

Reconnaissance aircraft counted hundreds of survivors in the water—most likely pilots who ditched.”

Mitscher inhaled.

“And Task Force 58?” he asked.

“All carriers operational, sir,” Burke said. “Minimal damage. Every ship accounted for.”

“And the pilots?”

Burke’s voice softened.

“We rescued nearly all of them.”

Mitscher nodded slowly.

Then he said the words that would enter naval history:

“It wasn’t skill.

It wasn’t luck.

It was logistics.”

June 21st, 1944

Pearl Harbor

0900 hours

A courier rushed into the operations center with a sealed message marked FLASH—the highest priority.

Nimitz opened it carefully.

Then read it.

Then read it again.

Then—

quietly, without theatrics—

he smiled.

The message was simple:

JAPANESE CARRIER FORCE DESTROYED.

U.S. LOSSES MINIMAL.

MARIANAS SECURE.

Around him, officers murmured prayers of relief.

Some shook hands.

Some stared in disbelief.

Victory in the Pacific wasn’t won.

But it had just been made inevitable.

Layton, the intelligence officer, approached.

“Sir…” he said softly, “with their air arm gone, the Japanese cannot defend the Marianas. And without the Marianas, Japan is within range of American bombers.”

Nimitz nodded.

“The war just changed,” he said.

This wasn’t a battle result.

It was a turning point.

Not flashy.

Not dramatic.

Not glamorous.

But decisive.

Nimitz didn’t cheer.

He didn’t boast.

He didn’t revel.

He simply said:

“Prepare the next operation.”

Because the Pacific was a machine, and machines only stopped when the job was done.

Aboard the last surviving Japanese carrier, a stunned Admiral Ozawa stared at the smoke rising from the horizon.

He had lost:

his flagship

his most experienced pilots

five carriers

six hundred aircraft

the war’s strategic advantage

But what haunted him more than the losses was the timing.

He whispered to his staff:

“We lost the battle on June 19th.”

Then, after a pause:

“No…

we lost it before June 19th.”

His staff looked at him, confused.

Ozawa continued:

“It was lost when the Americans arrived at Saipan before us.

When they concentrated their forces undetected.

When they were rested—and we were spent.”

He closed his eyes.

“That is not tactics.

That is not bravery.

That is not destiny.”

He opened them again, voice hollow.

“That is logistics.”

And he was right.

He knew it.

His officers knew it.

The entire Japanese Navy would soon know it.

June 22nd, 1944

Philippine Sea

As Task Force 58 recovered aircraft and refueled ships, Admiral Mitscher finally received a coded message from Pearl Harbor.

Nimitz’s words were characteristically brief:

WELL DONE.

CONTINUE OPERATIONS.

CWN.

Marc Mitscher folded the paper.

Burke stood beside him.

“What did he say, sir?”

Mitscher smirked.

“The usual.”

Burke chuckled. “I swear, the man could announce the end of the world in one sentence.”

“That’s because,” Mitscher said, “he’s seen worse.”

He gazed out over the ocean.

Burke hesitated, then asked:

“Sir, do you think Nimitz expected this exact outcome?”

Mitscher answered without hesitation.

“He didn’t hope for it.

He didn’t guess it.

He planned it.”

Burke raised a brow. “Planned… this?”

“All of it,” Mitscher said. “Every tanker at Eniwetok. Every fuel depot at Majuro. Every repair ship at Ulithi. Every sealed envelope. Every rendezvous point.”

He exhaled.

“Mitscher’s tactics didn’t win this battle,” he said quietly. “Nimitz’s system did.”

The Marianas Fall

June 15–July 9, 1944

Saipan and Tinian

With the Japanese fleet shattered, the U.S. Marines and Army continued the invasion of Saipan with overwhelming naval support.

Carrier planes bombarded Japanese fortifications daily.

Battleships shelled the beaches.

Landing craft poured troops ashore.

Logistics ships delivered supplies precisely on schedule.

Saipan fell.

Then Tinian.

Then Guam.

Three islands that formed the hinge of the Japanese defensive perimeter were now American.

And from these islands—

The U.S. would launch the B-29 Superfortress.

A bomber capable of reaching Tokyo.

The path to Japan was no longer theoretical.

It was real.

It was open.

It was inevitable.

Military historians would later call the Battle of the Philippine Sea:

“The greatest carrier battle in history.”

“The Marianas Turkey Shoot.”

“The definitive end of Japanese naval aviation.”

But the men who lived it—

the sailors, pilots, submariners, radar operators—

knew something different.

They knew this battle wasn’t about bravery alone.

Or luck.

Or superior technology.

It was about coordination.

Planning.

Systems.

Logistics.

And the invisible work that happens far from the front lines.

Work done in code rooms.

In supply depots.

In engineering shops.

In chart rooms.

In logistics offices.

In the mind of one admiral who understood that winning wars required more than strategy—

It required structure.

While the U.S. Navy grew more flexible, more decentralized, more adaptive—

the Japanese Navy remained rigid:

centralized planning

centralized supply

centralized authority

Every request needed approval from Tokyo.

Every movement required detailed planning.

Every decision was bottlenecked by bureaucracy.

When American submarines cut Japanese supply lines—

Japan had no backups.

No alternates.

No contingency planning.

They were a navy chained to its own command structure.

Their ships weren’t sunk at Saipan.

They were sunk years earlier—

the moment they clung to a system incapable of adapting.

In the months after the battle, Nimitz reflected on the operation’s success.

Not with pride.

But with calm certainty.

At a closed-door briefing, a junior officer asked him:

“Admiral… did we win at the Philippine Sea because we shot better? Because our pilots were superior?”

Nimitz shook his head.

“No,” he said softly.

“We won because America trained logistics coordinators.”

He tapped the Pacific chart with a weathered finger.

“We won in the seventy-two hours before the battle.”

He paused.

“And because we moved two hundred ships three thousand miles without the Japanese knowing.”

No one spoke.

Because the truth was bigger than the room could hold.

Nimitz continued:

“Battles are won by warriors.

Wars are won by the people who feed them, fuel them, and move them.”

He looked at his officers.

“That is the invisible victory.”

Years later, when the war was over, a Japanese naval officer—one who had survived both the Philippine Sea and the final surrender—was asked about the decisive battle.

He responded:

“We lost the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June.

But we lost the war in the seventy-two hours before the battle began.”

He was right.

Not because the Americans were smarter.

Not because they were stronger.

But because while Japan trained warriors—

America trained logisticians.

And in the Pacific—

logisticians decided the fate of empires.

After Saipan, the Pacific War accelerated.

Iwo Jima.

Okinawa.

Leyte Gulf.

The B-29 bombing campaign.

The encirclement of Japan.

Each operation grew larger.

Each operation required more ships.

More fuel.

More ammunition.

More organization.

And each one followed the template Nimitz had perfected during the Marianas:

decentralized execution

centralized logistics

prepositioned supplies

silent coordination

sealed orders

multiple contingency plans

By 1945, American fleets could maneuver across the Pacific with the precision of a wristwatch.

Japan could not.

By 1945, American forces could strike anywhere, anytime.

Japan could not.

And by 1945—

The Japanese fleet sat immobilized in harbor.

Not because it had been sunk.

But because it had no fuel.

No supplies.

No pilots.

No chance.

They were defeated not by fire—

but by starvation.

By isolation.

By logistics.

When the war ended on September 2nd, 1945, the world celebrated the admirals who won the battles:

Halsey.

Spruance.

Mitscher.

Turner.

Burke.

But the man who gave them the ability to win—

the man who built the system—

the man who turned the Pacific from a vast obstacle into a coordinated battlefield—

stood quietly in the background.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

A submariner.

A thinker.

A planner.

A man who believed in flexibility over rigidity.

Preparation over improvisation.

Trust over micromanagement.

Systems over ego.

He did not win the war by commanding from the bow of a carrier.

He won the war by building the structure that allowed others to do so.

In his memoirs, he wrote:

“Good logistics is not glamorous.

Good logistics receives no medals.

But good logistics wins wars.”

He was right.

The Final Image

Imagine it:

Two hundred American ships

spread across thousands of miles

moving silently toward a single point

across open ocean

with no radio

no signals

no coordination beyond sealed orders

and trust—

—and arriving within six hours of each other.

Not one Japanese scout saw them.

Not one Japanese commander suspected.

Not one Japanese admiral prepared.

That moment was not poetic.

It was not dramatic.

It was not cinematic.

It was simply:

Logistics.

Timing.

Systems.

Victory.

The Japanese lost the Battle of the Philippine Sea on June 19th.

But they lost the war—

in the seventy-two hours before the battle began.

Because that was when Nimitz moved two hundred ships three thousand miles without the enemy knowing.

That was when the Pacific shifted.

That was when victory became inevitable.

That was the invisible triumph.

That was the moment the Empire of Japan lost the sea.

And that—

was Admiral Nimitz’s masterpiece.

THE END

News

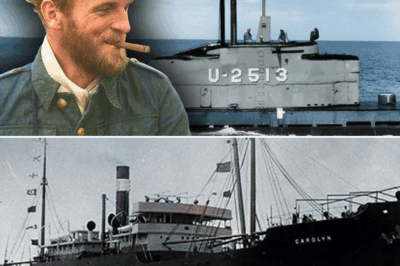

German U-Boat Ace Tests Type XXI for 8 Hours – Then Realizes Why America Had Already Won

PART 1 May 12th, 1945. 0615 hours. Wilhelmshaven Naval Base, Northern Germany. Coordinates: 53° 31’ N, 8° 8’ E. Captain…

IT WAS -10°C ON CHRISTMAS EVE. MY DAD LOCKED ME OUT IN THE SNOW FOR “TALKING BACK TO HIM AT DINNER”…

Part I People think trauma arrives like a lightning strike—loud, bright, unforgettable. But mine arrived quietly. In the soft clatter…

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When…

Part I I should’ve known from the moment Brian’s mother opened her mouth that the evening was going to crash…

I Returned From Prison To Find My Workshop Destroyed. Dad’s New Wife Mocked Me: “Ex-Con Meltdown!”

PART 1 I walked out of the county jail three weeks ago with a plastic trash bag, sixty bucks, and…

The Sniper Dropped His Rifle — And The Nurse Saw The Signal That Not Even The Marines Noticed

PART 1 Lauren Michaels had never imagined her life would lead her to a forward operating base in Helmand Province,…

Pilots Thought She Was a Mechanic — Until the F-22 Responded to Her Voice Command

Part I The sun hadn’t even topped the horizon when she arrived—barely a silhouette at first, walking with the slow,…

End of content

No more pages to load