Scratch.

Scratch.

Scratch.

Emma’s eyes snapped open in the dark.

For a few disoriented seconds, she didn’t know where she was. Only cold, only silence, only the feel of rough wool against her chin and the raw burn in her lungs from the dry mountain air.

Then she heard it again.

Scratch. Scratch. Scratch.

Not one set of claws. Not two.

Dozens.

The sound crawled through the cabin walls, wood protesting under the steady, frantic assault. The old door groaned in its frame. Snow-laden wind howled outside, trying to punch through the chinks and seams, pushing icy fingers through every gap.

Emma sucked in a breath so fast it burned. Her hand flew under the blanket and closed around the hunting knife she kept beside her mattress. The blade’s handle was slick under her damp palm. The knife shook with every thud of her heart.

Don’t panic. Don’t panic. Don’t—

The scratching grew louder. Angrier.

Something heavy slammed against the door. The hinges shuddered. Through the narrow gap at the floor, where the wood had shrunk away from the threshold over fifty winters, she saw movement.

Shadows.

Five. Ten. Fifteen. Twenty.

Wolves.

Their paws raked the wood, claws screaming over the grain. Their breath steamed in the air outside, visible even from where she lay, crystallizing instantly in the minus-thirty-five-degree blizzard.

Emma swallowed hard. Her throat felt like sandpaper.

She forced her legs to move, inching along the frozen floorboards. The cold bit through her long johns, through the thin mattress padding, straight into her bones. She crawled toward the door, never taking her eyes off the shadow slit at the bottom.

When she reached it, she pressed her cheek to the cold wood and put her eye to the crack.

Forty yellow eyes stared back at her in the half-light.

The dying fire behind her tossed a faint orange glow into the night. It caught those eyes and turned them into coals in the dark—unblinking, eerie, otherworldly.

But something was wrong.

They weren’t snarling. They weren’t lunging. The wolves didn’t move the way predators moved when they scented an easy kill.

No bared teeth. No foam. No frenzy.

Just scratching. Desperate, rhythmic scratching, like something begging to be let in.

The knife slipped from Emma’s hand and clattered to the floor.

She didn’t pick it up.

One wolf stood slightly apart from the rest. Bigger than the others. Silver-gray fur streaked with white, shoulders broader, legs thicker. A scar slashed diagonally across its left eye, white and puckered, the eye itself clouded and blind.

It wasn’t scratching.

It was staring directly at her, the way someone stares at a door they’ve stood in front of before. Like it knew this place. Like it knew her.

Like it remembered.

Emma’s legs buckled.

She slid down the wall until her knees hit the floor, her back pressed against the cold logs, her stomach twisting so hard she almost vomited.

The scratching intensified. Wood splintered near the hinges. A claw punched through, splinters spraying across the floor.

Emma scrambled backward until her spine hit the stone fireplace. The last of the coals glowed faintly in the ashes. Her hands found a wool blanket and yanked it up to her chest—a pathetic shield against twenty sets of jaws that could tear through it and her in seconds.

The wind screamed around the cabin eaves. Snow hissed against the windows like sand.

And still, there was no growling. No pack frenzy. Only that relentless, almost pleading scratching.

Emma’s breath came shallow and ragged. She forced herself up, legs shaking, and staggered to the small window near the door. Frost rimed the glass. The interior pane had iced over hours ago when the fire started to die.

She grabbed the wooden slat propped in the frame and pried it loose. Cold knifed into her face. Through the narrow gap, she looked out.

Her breath caught.

Several wolves lay flat in the snow, not attacking, just… down. Their sides barely moved. Others stood on legs that trembled like wet saplings in wind, ribs visible even through their thick winter coats.

Blood stained the snow beneath at least four of them. Deep gashes across shoulders and flanks, the kind of wounds a bear might leave—or steel might.

Near the door, beneath the line of scratching paws, a wolf pup convulsed weakly, tiny body jerking, breath coming in fast, shallow gasps. Its fur was crusted with ice. Its paws twitched, then went still for a terrifying second before jerking again.

They weren’t hunting.

They were dying.

Emma’s gaze flicked around the cabin.

Fireplace: four hours of wood left. Maybe five if she rationed.

Food storage: Three days of dried venison for one person. More if she stretched it. She had planned to make it last until the first thaw loosened the mountain’s grip.

Outside: A blizzard that would kill a human in twenty minutes without proper gear. An injured wolf in five. A pup in two.

If she did nothing, they would die.

She would live.

If she opened that door, she would die.

They might live.

Her hand moved before her brain caught up.

Fingers closed around the iron keys hanging by the hearth—heavy, worn smooth around the edges by her grandmother’s hands.

She walked toward the door, legs growing steadier with every step. Her heart hammered against her ribs like a trapped animal, but she wasn’t moving like someone who wanted to survive.

She was moving like someone who had nothing left to lose.

The bolt slid free with a heavy, final clunk.

Arctic wind punched through the opening like a fist. Snow swirled into the cabin, stinging Emma’s exposed skin, snatching her breath. The cold hit harder than fear.

The silver-gray wolf stepped across the threshold.

It moved slowly, placing each paw with care, as if remembering the feel of wooden floors under its pads. Snow melted in droplets from its fur, splattering onto the boards.

It didn’t lunge. Didn’t snarl. Didn’t bare its teeth.

It looked at her the way you look at someone you haven’t seen in years.

Like it remembered her.

Emma pressed back against the wall out of sheer reflex, hands flat, heart trying to punch through her ribs. She waited for the surge of bodies, for the pack to swarm inside and overwhelm her, to finish what hunger and cold had begun outside.

It never came.

The nineteen other wolves remained outside in the storm, huddled in the snow. They watched the doorway, ears pricked, eyes bright, bodies poised—but not one of them stepped onto the cabin floor.

It was as if they were waiting for something.

Permission, maybe.

Emma’s eyes tracked the silver wolf in front of her.

Up close, its damage was worse.

Its ribs sat like bars under the skin. The scar across its left eye was old—pale and tight, at least ten winters, maybe more. Around its neck, partially hidden by thick fur, she saw something else: a faint band of bare skin, ringed and slightly indented.

The mark a rope left when it tightened around living flesh.

The wolf turned its head.

Emma followed its gaze to the far corner of the cabin.

To the only photograph she owned—a faded print in a cracked frame, propped on a shelf above a stack of old field guides. The picture showed an elderly woman kneeling in a garden, hands sunk in soil, white hair pulled back in a practical braid.

Grandma Martha.

The wolf made a sound then. Not a growl. Not a howl.

Something softer. A low, broken noise that lived somewhere between a whimper and a moan. A sound that made the hairs on Emma’s arms stand up.

She had heard wolves call to each other at night, long, wild songs that rolled across the mountains like wind.

She had never heard this.

Her grandmother’s voice surfaced in her mind, as clear as if the old woman stood right behind her.

I saved a wolf once when it was just a pup. Caught in a hunter’s trap. Stayed with me three months before I released it back to the wild.

Emma had been ten when Martha told her that story. Sitting on the porch step, dangling her legs, skeptical.

“You’re making that up,” she’d said.

Martha had just smiled, the lines at the corners of her eyes deepening. “One day you’ll meet it,” she’d replied. “And you’ll understand.”

Emma hadn’t believed her then.

She believed her now.

The scar over the eye. The rope mark. The way this wolf looked at Martha’s photograph like it was visiting a grave.

This was that wolf.

And it had brought an entire pack to the only place it remembered as safe.

Emma moved again, not because she wasn’t afraid—she was—but because something in her chest, something buried under years of numbness and solitude, kicked hard.

The part of her that had watched Martha splint broken legs and stitch torn flesh, that had seen her grandmother pour herself out for wounded creatures that couldn’t say thank you, wouldn’t ever pay her back.

She edged sideways, keeping her back to the wall, and crossed to the small kitchen area.

The wolf’s good eye tracked her, but it didn’t move.

She opened the storage cabinet. Cold air spilled out. Inside, neat rows of cloth-wrapped bundles stared back at her—her insurance policy against the brutal mountain winter.

Three weeks of dried venison. A few jars of canned beans. Some oats. Coffee.

Everything she had.

Her hands gathered the venison without allowing herself time to think.

She walked back to the open doorway.

The wind clawed her hair around her face. Snow swarmed against her legs, trying to push past her into the warmth.

Emma threw the meat into the snow.

She expected chaos.

Snarls. Snapping jaws. A pile-on, claws and teeth and fur, a tumble of bodies desperate enough to turn on each other.

She got something else.

The silver wolf moved first.

It stepped outside, onto the snow. Bent its head toward the meat. Sniffed once, twice.

Then stepped back.

The wolves with the worst injuries went in first. The ones lying flat, too weak to stand, were helped to their feet by others nudging at their flanks. The pup was pushed gently forward until it found a strip of meat and tore into it with tiny, trembling jaws.

Only after the wounded and the young had eaten did the rest approach, in some orderly sequence Emma couldn’t decode but recognized as deliberate.

The silver wolf ate last.

Emma stood in the doorway, watching, the cold biting through her socks, her hands numb, her mind racing.

This wasn’t mindless. This wasn’t wild chaos.

This was a hierarchy. Discipline. Priorities.

This was a family.

Her eyes went to the injured ones again.

Two bore deep bite marks—raked along their backs and shoulders, probably from a bear’s claws. But others had wounds that were too clean, too precise.

Long, straight cuts. Circular punctures.

The kind of damage steel made.

Traps.

Someone had been hunting this pack.

One young female lay apart from the others, barely breathing. Her belly was gashed open, the wound edges swollen and angry. The snow around her was stained a pale, watery pink. Infection radiated in red streaks under the skin.

She’d be dead by morning.

Unless—

Emma turned and crouched beside the fireplace.

She dug her fingers into the crack between two floorboards and pried. The board came up with a reluctant creak, revealing a shallow cavity beneath.

Martha’s medicine cache.

Bundles of dried herbs carefully labeled in the old woman’s shaky handwriting. Tinctures in corked glass bottles. Rolls of linen bandages. A bone-handled needle and a spool of surgical thread.

Everything her grandmother had used for forty years to patch up the forest’s wounded.

Emma grabbed what she needed and headed back outside.

The pack stiffened as she approached the injured female. Ears flattened, lips curled just enough to show teeth. Warning.

But the silver wolf stepped between Emma and the others, long body blocking their line of sight. It turned and faced its own pack, chest rumbling low. The others backed away.

Emma knelt in the snow.

The injured wolf’s breath was ragged and fast. Her eyes rolled but never settled. When Emma touched her side, the wolf flinched but didn’t bite. Didn’t even snap.

Fear and training fought inside Emma.

Martha’s voice won.

We have a debt to the forest, Em. We take wood, food, medicine. When it needs something from us, we give back.

Her fingers moved with surprising steadiness.

She cleaned the wound with melted snow and herbal antiseptic, breathing through her mouth to blunt the metallic tang of blood and infection. She pressed the edges of flesh together and began to stitch, thread pulling skin tight with each careful pass.

The wolf whimpered once, a high, pained sound.

Above her, she could feel the silver wolf’s gaze like a weight on her hands. It watched every movement, every stitch.

Another memory surfaced, uninvited.

A gas station. The smell of diesel and burnt coffee. Cracked tile under her too-big shoes, held together with bits of rope because her mother couldn’t afford laces.

She was three.

She sat on a bench outside, clutching a torn stuffed bear, watching cars come and go, waiting.

Her mother had told her, “Stay here. I’ll be right back.”

She never came back.

Emma hadn’t cried that day. Even at three, she had already learned that crying changed nothing. That calling for help only emphasized the fact that no one was coming.

She had sat on that bench for six hours until an old pickup rolled off the highway.

The woman who climbed out had dirt under her fingernails, soil on her jeans, and white hair escaping from a messy braid.

She had walked past Emma, then stopped, turned, come back.

She hadn’t asked one of those questions adults always asked kids alone in places they shouldn’t be.

Not “Where are your parents?” or “What are you doing here?”

She’d asked, “Are you hungry?”

Emma had nodded.

Martha bought her a sandwich. Sat next to her on the bench. Didn’t pry. Didn’t push. Just stayed.

After an hour, she’d said, “I have a cabin up the mountain. Warm bed. Hot food. You can stay as long as you need.”

Seventeen years later, Emma was kneeling in the snow outside that cabin, stitching a wild wolf back together with the same hands Martha had taught to sew meaty, bleeding flesh.

The blizzard had eased without her noticing. The wind had dropped to a sullen gust. Snow drifted in soft, lazy flurries instead of sideways knives.

Emma tied off the last stitch and sat back on her heels, breath puffing in the cold.

The injured female’s breathing had slowed. The frantic, panicked flick of her eyes had settled. Her belly rose and fell, the wound edges dark but no longer weeping.

Emma’s fingers shook as she cleaned up her tools.

The pup had stopped convulsing. It slept now, tucked in the middle of the pack, enclosed on all sides by warm bodies. Steam rose from the wolves’ fur into the cold dawn.

Fourteen wolves sprawled in a wide circle in front of her cabin.

The silver one remained standing.

It moved closer, each step deliberate, until it stood within arm’s reach. For a long moment, it simply stared at Emma. Then, slowly, it lowered its head.

Just a fraction.

Just enough.

The simple, small gesture hit Emma harder than any words could have.

You did enough, it seemed to say.

You paid the debt.

It was the first time in years anyone—anything—had suggested that what she did mattered.

That she mattered.

Which is why, when she heard the distant growl of an engine laboring through deep snow, she didn’t run inside and bar the door.

She stood in the snow, surrounded by wolves, and faced the road.

The county sheriff’s truck fought its way up the mountain like an old man climbing stairs with a pack of bricks on his shoulders.

The engine whined. The tires spun, throwing plumes of powder. Headlights flickered between the trees, cutting swaths through the gray morning.

Emma watched it approach, heart tightening.

The road hadn’t been passable for three days. No one should be out in this. No one came up here without a reason.

The silver wolf’s ears flattened. It stepped in front of her.

When the truck finally ground to a halt fifty yards from the cabin, stuck in a drift, the engine coughed and died.

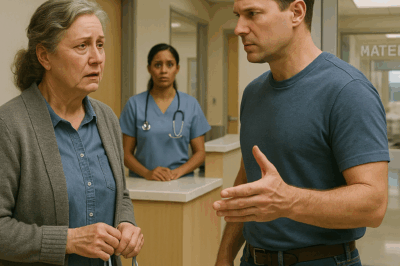

The driver’s door opened.

A man climbed out, tall despite the heavy parka, broad-shouldered in that particular way men get from decades of labor and habit. He had a salt-and-pepper beard, dark eyes, and the weary stance of somebody who’d seen more than he’d ever talk about.

A sheriff’s badge glinted on his chest.

His hand rested on the butt of his holstered pistol as he took in the scene—wolf pack, woman, cabin.

Twenty wolves rose as one.

They didn’t advance. They didn’t snarl. But they formed a loose line between Emma and the stranger, a wall of fur and muscle and amber eyes.

The silver wolf moved to the center, directly in front of the cabin door.

Guardian of the threshold.

The sheriff stopped.

Slowly, deliberately, he raised both hands to shoulder height, palms out.

“Emma Collins!” he called, voice carrying easily over the stiff morning air. “I’m Sheriff Daniel Hartley. I’m alone. I mean no harm.”

Emma didn’t answer.

She stood behind the wolves, one hand still resting in old silver’s fur, fingers buried in the thick ruff at his neck.

In two years, she’d had exactly three human visitors: the UPS driver who’d gotten lost once, a social worker who tried and failed to convince her to leave the mountain after Martha died, and a ranger who’d come by to post a notice about fire danger.

None had stepped inside.

None had gotten past the walls she’d built.

This one felt different.

“They won’t let you closer. Not yet,” she finally said, surprised at how rough her own voice sounded. It felt like a rusty hinge.

Hartley nodded. “I can see that.”

He glanced at his truck, then up at the sky, then at the cabin again.

“If it’s all right with you, I’ll wait here,” he said. “Storm’s coming back. I’m not getting this thing out of that drift anytime soon.”

He backed up and sat on the hood of his truck, hands still visible, posture relaxed.

Then he just… waited.

The blizzard returned that afternoon.

For five more days, the mountain disappeared under a white curtain.

Wind howled. Snow built drifts taller than Emma’s head. Temperatures dropped. The world shrank to the cabin, the truck, and the circle of wolves between them.

On the first day, Emma brought Hartley blankets and a thermos of coffee.

She walked through the wolf line. They parted for her like water around a stone, tense but accepting. She passed the blankets across the invisible boundary and retreated.

“Thank you,” he said.

On the second day, practicality trumped pride.

Hartley’s truck was an icebox on wheels. When he tried to approach the cabin again, the wolves bristled. But they no longer formed an impenetrable wall. They shifted, left gaps.

He made it to the porch steps before old silver moved to block him, body going rigid.

Emma opened the door.

“You can come in,” she said. “But slowly.”

He slept in the corner that night, rolled in blankets, as far from her as the tiny room allowed. The wolves remained outside, but the silver wolf lay on the porch, nose pressed against the bottom of the door, watching through the crack.

On the third day, Hartley helped change bandages on the injured wolves.

Emma gave instructions in short, clipped sentences.

“Hold this here. Not too much pressure. Keep your voice down. Move slow.”

His hands were clumsy at first, more used to handcuffs and paperwork than field medicine. But he listened. He did what she asked. When it was over, Emma noticed something had shifted in the pack’s posture toward him.

Still wary. Still watchful.

But no longer hostile.

“You’re good at this,” Hartley said that evening, nodding toward the sleeping wolves.

“My grandmother taught me,” Emma replied.

He paused in the act of sipping coffee.

“Martha Collins?” he asked.

Emma stiffened. “You knew her?”

He nodded slowly. “Everyone in Hollow Creek knew Martha.”

He stared into the fire for a long time, the flames painting familiar stories into his lined face.

“She treated my wife fifteen years ago,” he said quietly. “Cancer. Doctors gave her six months. Martha’s herbs gave us three more years.”

His jaw worked.

“Best three years of my life.”

Emma didn’t know what to say. So she said nothing.

That night, she dreamed of Martha’s calloused hands wrapping a warm mug around her small fingers, of a kitchen filled with the scent of drying herbs, of a voice that never once called her a burden.

On the fourth day, Hartley told her what the town thought of her.

“It’s not everyone,” he said, rubbing tired eyes. “But enough.”

He told her about Pastor Thomas Wheeler and his weekly sermons about cleansing the community. About the way people whispered “witch” under their breath when her name came up. About the way some parents crossed the street when they saw her in town buying supplies once a year.

Emma took it all in.

None of it surprised her.

You can’t be hurt by a punch you see coming. She’d seen this one her whole life.

“They’re wrong,” Hartley added. “I’ve seen enough in four days to know they’re wrong.”

On the fifth day, the wolves dragged a rabbit carcass onto the porch and dropped it at Emma’s feet.

She cooked it and shared the meat with Hartley.

It was the first meal she’d shared with anyone since Martha’s funeral.

Something in her loosened.

She found herself humming as she mixed salves. Her shoulders lowered from their habitual hunch. Sleep came easier. The silences between her and Hartley stopped being walls and started being… comfortable.

On the sixth morning, the sky cleared.

Sunlight spilled across the snow in blinding sheets, turning the whole mountain world into a glittering field of diamonds.

Hartley stood on the porch, squinting toward the road.

“You should come down to town sometime,” he said. “Let folks see you as you are. Not as they’ve decided you are.”

Emma shrugged. The idea made her skin itch.

“They won’t want me there.”

“Some won’t,” he agreed. “Some will surprise you.”

He pulled on his coat. “I can’t promise I can change everyone. But I’ll make sure no one bothers you up here. You have my word.”

It was the first promise anyone had made her in years that sounded like it might actually be kept.

They walked together to the truck.

The path the wolves had worn through the snow made for easier walking. At the driver’s door, Hartley hesitated, hand on the handle.

“Emma,” he said.

His tone had changed. A heavier note in it.

“There’s something I never told you.”

She waited.

“Your mother,” he began, then stopped. He looked at the trees, at the sky, anywhere but her face. “She didn’t abandon you.”

Everything in Emma went still.

For seventeen years, that had been the bedrock truth under everything else. Her mother left. Didn’t want her. Didn’t love her. End of story.

“What?” she whispered.

Hartley climbed into the truck.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I should have told you a long time ago. I’ll explain everything soon. I promise.”

The engine caught on the third try. The truck backed, turned, and pulled away down the mountain, leaving Emma standing in the snow, heart pounding in a new, unfamiliar rhythm.

Old silver pressed against her leg.

She didn’t notice her hand finding his fur. Didn’t notice the cold.

Her mother didn’t abandon her.

Then what happened?

And why had everyone let her believe that lie for seventeen years?

She found the box three days later.

Spring came reluctantly to the mountains, creeping in like a shy guest. Snow melted along the edges of rocks, revealing patches of brown earth. Icicles dripped themselves to death one slow drop at a time. The air smelled different—wet and raw and full of possibility.

Emma was pulling back rugs and sweeping winter grit from corners when she noticed the way one particular floorboard near Martha’s old rocker always creaked just a little… wrong.

It wasn’t the familiar music of old wood. It was sharper. Looser.

On her knees, she pressed at the board’s edge.

It shifted.

Her stomach tightened.

She slid her fingers under the edge and lifted. The board came up, revealing a shallow compartment underneath.

Inside lay a metal box, rusted at the corners, heavy in a way that spoke of more than just paper.

A padlock hung from the latch, its brass corroded to a dull green.

Emma’s hand went to the chain around her neck almost reflexively. Martha had pressed the chain into her palm the night before she died, closing the old woman’s fingers over Emma’s hand.

“You’ll know when you need it,” she’d whispered.

Emma had never known.

The small brass key slid into the padlock like it remembered the way. The lock clicked open, loud in the quiet cabin.

Inside the box, wrapped in an old oilcloth, were photographs and letters tied with a faded ribbon. Beneath them, a folder of official-looking papers.

The first document was a birth certificate.

Her own.

Emma Rose Collins.

Mother: Sarah Anne Collins.

Father: Unknown.

Grandmother: Martha Ellen Collins.

Grandmother.

Not legal guardian. Not neighbor. Not kind stranger.

Blood.

Emma read the line three times, the letters blurring.

She picked up the photographs.

In the first, a young woman with Emma’s eyes and Emma’s stubborn jaw held a newborn in a threadbare blanket. The baby’s face was scrunched in indignation. The woman’s smile was tired but radiant.

On the back, in Martha’s rounded handwriting, were the words: Sarah and Emma – 2 months.

The second photo showed a younger Martha standing beside the same woman. They were in front of this cabin. The mountains rose behind them. Both women were laughing at something just out of the frame.

The letters smelled faintly of old paper and dried lavender.

The first was dated twenty years ago.

Sarah’s handwriting slanted small and tight.

She wrote about being nineteen and foolish, about falling for a man who’d promised forever and delivered nothing. About finding herself pregnant and alone. About going to Pastor Wheeler for help and being told she was a stain on Hollow Creek, a bad example, a danger to young women.

She wrote about the town council deciding, under Wheeler’s guidance, that she had to leave. That if she didn’t, Martha would be punished instead—tax audits, health inspectors, zoning violations. Every petty tool of institutional cruelty.

The second letter came from a city three hundred miles away.

Sarah wrote about waitressing double shifts, about a tiny apartment that leaked when it rained, about Emma’s first word (mama), Emma’s first steps (straight into a table), Emma’s first laugh (at a dog chasing its own tail).

She wrote, I’m coming back for her, Mama. As soon as I have enough saved, I’ll come home. We’ll fight them together. They can’t scare me forever.

The third letter was dated seventeen years earlier, three days before the gas station.

I’m leaving tomorrow. I’ve saved enough for a lawyer. Wheeler can’t touch us if we have the law on our side. I’ll drop Emma at the station in Miller’s Creek. It’s only an hour from you. I have to sign some papers in the city first. But I’ll be right behind her. Tell her I love her. Tell her Mama’s coming.

The letter ended with a smear, ink blurred as if by tears.

Behind it, clipped carefully, was a newspaper.

The headline read:

SINGLE MOTHER KILLED IN HIGHWAY COLLISION

The date was two days after the letter.

Emma sat back hard, the breath punched out of her lungs.

She saw herself on the gas station bench. Her too-big shoes. Her torn bear. Six hours of waiting.

Her mother wasn’t late.

Her mother was dead.

On the road home.

The last document in the box was a property deed, yellowed and fragile.

It confirmed what she now knew: the cabin and surrounding forty acres belonged to Martha Collins, and now to Emma herself.

Attached to the deed was a surveyor’s report from fifteen years ago. It mentioned mineral deposits under the property. Valuable ones.

Iron ore. Maybe more.

A handwritten note clipped to the report bore Martha’s sharp, heavy script.

Wheeler keeps asking about the land. Offered to buy it three times this year. I told him I’d rather burn it down. He didn’t like that answer.

Emma’s fists clenched around the papers.

Her grandmother had known.

She’d known about the minerals, known about Wheeler’s interest, known that he’d driven Sarah away, known that his actions had indirectly killed her daughter on the road.

She’d kept this secret to protect Emma—not from the truth, but from the man who would stop at nothing to get this land.

The radio on the shelf crackled, breaking through Emma’s storm of thoughts.

She turned it on without thinking.

“—and I say unto you, brothers and sisters,” Pastor Thomas Wheeler’s voice boomed across the static, “we have allowed darkness to fester in our midst. A woman living up that mountain with wild beasts, unnatural, ungodly. Our good sheriff spent nearly a week trapped in her den, and who knows what corruption has taken root in his soul.”

Emma’s jaw tightened.

“I have spoken with the town council,” Wheeler went on. “Action must be taken. We cannot allow this threat to our children, our livestock, our very way of life to continue unchallenged.”

Emma turned the radio off.

The wolves lifted their heads from their resting places outside, senses tuned to her shifting mood.

Old silver stood, shook snow from his fur, and pressed his scarred head against the window.

Emma stared at the box on the table. At the letters. At the obit clipping.

At twenty years of lies.

She’d spent two decades believing she wasn’t worth staying for.

Finally, she knew:

Her mother hadn’t left her.

She’d died trying to come back.

They came three days later.

Engines.

Multiple.

Emma heard them before the wolves did, a low, distant rumble under the afternoon wind. She was in the garden, clearing dead stalks from Martha’s old beds, turning soil with a rusted spade, trying to remember how to breathe evenly.

Old silver’s head snapped up.

He growled, a warning that rolled through his chest, low and building. Other wolves followed suit, muscles tensing.

Through the trees, Emma saw the convoy.

Trucks. At least five. Headlights on despite the pale sun. Snow flung from tires in dirty arcs. Men rode in the beds, silhouettes bristling with rifles and something else—torches.

At the front, in a black sedan that looked like it had never seen a dirt road in its life, sat Pastor Thomas Wheeler.

The wolves moved without a sound.

They flowed out of the treeline and formed a line between the cabin and the approaching vehicles. Hackles rose. Tails stiffened. They didn’t snarl.

They just… stood.

The trucks lumbered to a stop at the edge of the clearing. Doors opened. Men poured out, boots crunching on hard snow, forming a crude semicircle.

Wheeler emerged last, wrapped in a thick coat, white hair combed perfectly, face arranged into a mask of sorrowful duty.

“Emma Collins,” he called, voice polished by decades of preaching. “We have come to save you from yourself. To deliver you from the evil you have embraced.”

Emma stepped onto the porch.

The letters were in her pocket. The clipping, too. Phenomena of paper and ink with the weight of bullets.

Old silver took his place at her side, one eye fixed on Wheeler with a look that made even some of the armed men inch back.

“Save me?” Emma said, her voice carrying more strength than she felt. “Like you saved my mother?”

A brief flicker, a crack in Wheeler’s mask.

“Your mother,” he said, his tone dripping with pity, “was a troubled woman who made sinful choices. Her fate was God’s judgment.”

“No,” Emma said, and held up the clipping. “Her fate was a car accident on the highway, driving home to get her daughter. The daughter you made sure she had to leave behind.”

Murmurs rippled through the crowd.

Some of the older faces tightened. The story they’d been told about Sarah Collins didn’t include highway accidents.

Wheeler’s smile turned brittle.

“Lies,” he said. “Fabrications from a disturbed mind. This is how the devil works, my friends—through manipulation, through false accusations. This woman has lived among wild beasts so long she’s become one herself.”

He reached into his coat and pulled out a revolver.

“These animals,” he said, his voice rising in righteous fury, “are a danger to our community. If no one else will act, I will cleanse this evil myself.”

He raised the gun.

Not at the wolves.

At old silver.

Emma moved.

She stepped off the porch, boots hitting the snow with more force than her thin frame should have had, and walked straight into the line of fire.

She put herself between Wheeler and the wolf, arms out, palms visible.

“Shoot me, then,” she said. “You already killed my mother. Might as well finish what you started.”

Gasps from the men. A sharp intake of breath from someone in the back.

Wheeler froze.

The gun wavered.

For the first time since she’d known of him, Emma saw the man beneath the pastor—the small, petty creature who’d destroyed a family over land and minerals and the need to feel powerful.

Before anyone could move, another engine sound cut through the tension.

Sheriff Hartley’s truck burst into view, tires kicking up a spray of slush. He slammed on the brakes, flung open the door, and stepped out with his hand already on his holster.

“Wheeler!” he shouted. “Lower that weapon. Now.”

The pastor’s jaw clenched.

“This is between me and the witch,” he spat.

Hartley strode forward, boots crunching.

“This is between you and the law,” he shot back. “And you’re already about twenty years overdue.”

He held a folder in his other hand. Papers flapped in the cold breeze.

“I’ve been digging,” Hartley said, voice loud enough for everyone to hear. “Land surveys. Mineral rights. Purchase offers. Funny thing, Pastor—your name’s on an awful lot of them.”

He held up a sheet.

“You filed mineral rights paperwork on Martha Collins’ land three months before anyone else knew what was under it.”

More murmurs. Louder this time.

Wheeler’s face twisted.

“Everything I did was for this town,” he hissed. “To keep it from falling into sin and corruption.”

“You drove a young woman out of town,” Hartley said. “You threatened her mother’s home. You set into motion the chain of events that led to Sarah Collins dying on that highway.”

He pointed at Emma.

“You left her granddaughter to grow up believing she wasn’t wanted. So you could get your hands on forty acres of rock.”

The town’s people turned their eyes to Emma.

Some with shame. Some with dawning horror. Some with a kind of tentative, fragile sympathy.

Wheeler’s mask shattered.

He raised the gun again.

“If the state won’t act,” he snarled, “God will.”

What happened next, no one could ever describe in a way that did it justice.

Later, different people would remember different details.

Billy’s father would swear he heard the wolf move before he saw it.

Linda Mercer would say all she saw was a streak of silver.

Hartley would remember thinking, Too far. Too fast. We’ll never get there in time.

Old silver crossed the clearing like a shot fired from a cannon.

He launched himself into the air just as Wheeler’s finger tightened on the trigger.

The crack of the gun split the cold quiet.

The bullet hit the wolf in the shoulder.

Momentum carried his body into Wheeler. They crashed to the ground, the revolver skidding across the ice.

Chaos erupted.

The wolves surged, then stopped dead at a low bark from old silver, even as he lay bleeding.

Men shouted. Hartley lunged for the gun. Billy’s father tackled Wheeler’s son.

Emma ran.

She reached the wolf in seconds, then dropped to her knees so hard the breath whooshed from her lungs.

Blood soaked the snow under his shoulder, soaking into his silver fur. The same shoulder that bore the old scar from the trap.

“No,” she whispered. “No, no, no.”

Her hands, which had been so steady stitching a wound days earlier, shook as she pressed them against this one.

“Stay with me,” she begged. “You don’t get to leave. Not you, too.”

Wheeler groaned somewhere to her left. Towns people pinned him down, rage and betrayal mixing in the shouts.

Emma didn’t hear them.

Her world shrank to the heartbeat she could feel under her palms. Weak. Fast. Erratic.

“Please,” she whispered. “I can’t do this alone.”

A rough hand closed over her shoulder.

Billy’s father knelt beside her, his face wet.

“Tell me what to do,” he said.

Linda was suddenly there too, first aid kit snapped open, hands already reaching for gauze and tape. Hartley barked into his radio for an emergency vet. People Emma had never spoken to knelt in the blood and snow.

“What do you need?” Linda asked. “Tell us.”

Emma blinked hard, fighting to see through tears.

“Pressure here. Here,” she said, guiding hands to compress around the wound. “We have to slow the bleeding.”

They did.

The vet came. The wolf survived.

Everything else happened in a blur.

State wildlife officers arrived, papers in hand, prepared to “solve” the wolf problem. They were met not with a town united in fear, but with one divided, wrestling with a story they’d never bothered to ask for.

They investigated. They listened. They watched a pack of wild wolves allow towns people to help them. They saw a young woman risk her life again and again for creatures she had every reason to fear.

And they saw a pastor’s greed laid bare.

In the end, they left without firing a single tranquilizer or bullet.

“We’ll monitor,” the lead officer said. “But I’m not exterminating a pack that just saved a kid and took a bullet for a woman who’s been more responsible than half the ranchers in this county.”

Wheeler was arrested.

Years of buried complaints suddenly had witnesses willing to speak. Financial improprieties. Abuse of authority. Coercion.

The man who’d stood at the pulpit warning of wolves in sheep’s clothing turned out to be something worse.

The wolves went back to the forest.

Old silver spent three days in Linda’s storage shed, recovering from surgery. Emma and Hartley took shifts watching him, talking in low voices, the old wolf’s chest rising and falling in slow, steady breaths.

“You know,” Hartley said one night, watching Emma stroke the wolf’s fur, “if Martha could see you now, she’d say, ‘Told you you’d meet him.’”

Emma smiled, a small, tired curve of her mouth.

“Yeah,” she said. “She would.”

Summer slid into fall. The cabin changed with the seasons.

Emma planted more than vegetables in the garden. She planted flowers—wildflowers she’d transplanted and coaxed into beds, splashes of purple and gold and blue around the cabin’s weathered logs.

On Saturdays, she drove into town in Hartley’s truck and opened the small apothecary she’d set up in the back of Linda’s store. Shelves held jars of salves and tinctures with labels written in her neat, careful hand.

People came.

At first, many did it with the cautious curiosity of folks approaching a caged animal.

Then some came because Linda swore Emma’s tendon salve worked better than any pharmacy ointment. Because Billy’s little sister stopped having asthma attacks after using her steam herbs. Because Billy’s father’s old shoulder injury finally loosened after he started taking her tincture.

People talked.

The words witch and crazy got quieter.

The words healer and Martha’s granddaughter got louder.

Emma never went to church.

Nobody tried to make her.

Old silver spent more time sleeping in the sun than running with the pack now. Age had crept into his joints, turning his lope into a stiff walk. But his eye stayed bright. His presence on the porch became part of the town’s lore.

The kids called him “Grandpa Wolf.” They’d stare up at him when their parents brought them by the cabin to “pick up medicine,” which often also involved Emma showing them how to plant seeds or identify animal tracks.

Once, a little girl looked at the old wolf and whispered, “Did he really save you?”

Emma’s hand settled on his head.

“Yes,” she said. “More than once.”

The girl nodded solemnly and offered the wolf a piece of jerky with all the gravity of a holy offering.

Old silver took it carefully, teeth never touching her fingers.

That night, Emma sat on the porch with him and watched the sun bleed orange across the mountain peaks.

“You waited fifteen years,” she said softly, scratching the fur between his ears. “You remembered this place. You remembered her. You came back when you needed help.”

His eye slid toward her, slow and fond.

Maybe, his expression seemed to say.

Or maybe I came back when you did.

Either way, the debt was paid.

Wolves are not sentimental creatures.

But some bonds don’t care what shape you wear.

Years later, in a town that had learned slowly, painfully, how to doubt its own fear, people would tell the story of that winter.

They’d talk about the blizzard.

About twenty wolves scratching at a girl’s door.

About how everyone expected blood and death and fear.

About what actually happened instead.

They’d say, “That was the day Hollow Creek started to change.”

They’d point at the cabin on the mountain, with its explosion of wildflowers and its apothecary sign swinging gently in the wind, and they’d say, “That’s where the wolf woman lives. She saved my boy’s life. She stitched my husband’s leg. She forgave us when we didn’t deserve it.”

And sometimes, when the light was just right, you could stand at the edge of the clearing and see her on the porch.

A woman with hair in a practical braid, hands stained with soil and tinctures.

An old wolf stretched at her feet.

She’d be talking.

Or laughing.

Or just sitting with her head tilted back, eyes closed, face turned to the sun.

You could look at that and remember that family is not always blood.

Sometimes it’s the person who pulls into a gas station and offers you a sandwich.

Sometimes it’s the sheriff who decides the mountain witch deserves a fair hearing.

Sometimes it’s the wolves who show up in a blizzard and remind you that you’re not as alone as you think.

And sometimes, if you’re very lucky, it’s all of those things at once.

If you’ve ever felt like Emma—forgotten, misunderstood, convinced nobody would come for you—remember this:

Even in the middle of a blizzard, sometimes the scratching at your door isn’t danger.

Sometimes, it’s the unexpected beginning of a pack.

THE END

News

My Son Threw Me Out Of The Hospital When My Grandson Was Born—He Said She Only Wanted Family

The precise moment my heart shattered wasn’t when the doctors told me my husband was dead. It wasn’t when I…

CH2 – The Invisible Technology That Sank 43 U-Boats in One Month

May 1943 North Atlantic The Atlantic looked almost peaceful. The sea rolled in slow, lazy swells under a gray sky,…

The fire alarm went off, but our teacher locked the door – said “nice try, but nobody’s getting out”…

I was halfway through Question 17 on my AP Chemistry final when the fire alarm started shrieking. If you’ve never…

CH2 – The General Who Disobeyed Hitler to Save 20,000 Men from the Falaise Pocket

August 16th, 1944 1600 hours A farmhouse near Trun, France General Paul Hausser stood over a battered oak table,…

CH2 – German Pilot Ran Out of Fuel Over Enemy Territory — Then a P-51 Pulled Up Beside Him

March 24th, 1945 22,000 feet above the German countryside near Kassel The engine died with a sound Franz Stigler would…

Fired Day 1, I Owned the Patents: CEO’s Boardroom Downfall

By the time the email popped up on her screen, Elena Maxwell hadn’t even finished adjusting the chair. She…

End of content

No more pages to load