“Your sister’s big day matters more than your surgery” Mom said as I lay in pain. Years later, my sister joined my hospital with a smile. On day one, I walked in wearing the chief of surgery badge. She froze. The silence said it all.

Part 1

The first sound was small.

Just a click, really. The metal teeth of the badge clip snapping over the lapel of my white coat—small, final, clean.

I smoothed the fabric down out of habit. The laminated ID settled against my chest, still stiff from being printed.

NAME: DR. NORA LENNOX

TITLE: CHIEF OF SURGERY

The letters looked unreal. Like someone else’s profession had been glued onto my life.

The hallway outside Operating Theater 3 buzzed with its usual chaos—orderlies pushing beds, nurses scanning barcodes, the faint hum of fluorescent lights and distant monitors. It was the kind of soundscape I’d lived in for so long that silence felt foreign.

Which is why I noticed it so sharply when the sound around me folded inward.

“Nora?”

Her voice arrived first. Light, bright, rehearsed.

I turned.

Claire stood at the far end of the hall, one hand still poised mid-air like she’d been about to push open the double doors. Her hair was styled perfectly, of course—soft waves that looked expensive but effortless. The HR-issued visitor badge was clipped high on her blouse like a brooch. She was smiling.

Then her eyes dropped to my chest.

To the new badge. To the line beneath my name.

I watched the smile die.

It didn’t fall all at once. It froze, like someone had hit pause on her face. The corners of her mouth stayed turned up by force of habit, but everything in between changed. Her pupils flared. The muscles along her jaw twitched. Her fingers tightened around the portfolio clamped in her other hand.

The hallway didn’t stop moving. A nurse brushed past her. A porter pushed a cart of supplies past me. Someone paged anesthesia overhead. Life went on. Hospitals don’t care about your drama.

But in the space between us, there was nothing.

No words. No noise.

Just recognition.

Just memory.

Just ten years collapsing into a single stretched-out heartbeat.

She didn’t look up at my face.

Not at first.

She stared at the badge like it had spoken out loud.

Chief of Surgery.

My hospital.

My department.

My rules.

A resident squeezed by with a tray of instruments. “Morning, Dr. Lennox,” he said, barely glancing at me.

I nodded. “Morning, James. Don’t let Fisher rush that consent. Full disclosure.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, pivoting toward pre-op.

When I turned back, Claire finally dragged her gaze up from my chest.

“Nora,” she said again. My name sounded different this time. Less like a greeting. More like a question she already knew the answer to but hated.

“Claire,” I answered.

Close up, I could see the fine lines starting at the corners of her eyes, softened with makeup, the faint strain around her mouth. She was thirty-four now, two years younger than me, but she still moved like the world was a camera pointed in her direction. Shoulders back. Chin up. Practiced.

“I didn’t…” She swallowed. “HR said the chief would be meeting the new hires. They didn’t say it was you.”

“They didn’t ask my permission to tell you,” I said. “Orientation starts in five.”

Her fingers flexed again around the portfolio. I wondered what was in it. Printed copies of her CV. Recommendation letters. The same sweeping arc of success she’d been handing people for years, half of it borrowed from my footprints.

“Nora,” she said a third time, trembling on the edge of something that might have been apology if she’d known what it looked like. “I—”

The pager at my hip vibrated.

PACU RN: DR LENNOX, PT LYMAN ASKING FOR YOU

BP STABLE. CLEARED FOR VISIT IF ABLE.

I silenced it.

“Conference room B,” I said. “End of the hall. Left side. You’ll recognize the crowd.”

“I—okay,” she said. She stepped aside as two scrub techs wheeled a supply cart past. The hem of her blouse brushed the trolley and she flinched, pressed against the wall as if the corridor itself had turned hostile.

I walked past her.

Her perfume—jasmine and something bright—hit me for a second. The same brand she’d worn since high school, when she’d trailed it through the house like a flag, a sweet, suffocating ghost that settled in my clothes without asking.

I didn’t look back.

The badge thumped softly against my chest with each step. The weight was new. The weight was earned.

Outside Conference Room B, I paused.

Through the narrow glass panel, I could see the department heads already gathered. Legal was there, and HR. Quality Assurance. A couple of senior attendings. The empty chair near the end of the table with a folder in front of it had a nameplate already in place.

DR. CLAIRE LENNOX–MILLS

CARDIOTHORACIC SURGERY

I took a breath.

This meeting wasn’t just about her. It was about the audit. About authorship discrepancies across multiple institutions. About a resident who’d reported their research being credited to someone else and thought no one had listened.

It was about ten years of silence finally finding its voice.

But before I could open the door, before I could step into the room where everything I’d prepared was laid out like an incision ready to be made, the memory hit.

Not gently.

Not kindly.

It crashed over me in antiseptic taste and fluorescent buzz and the sight of another ceiling, another hospital, another time I’d been flat on my back and powerless.

The day my appendix ruptured.

The day my mother told me my sister’s big day mattered more.

The day I learned exactly where I ranked in the hierarchy of my own family.

Part 2

The pain started like a cramp.

I was twenty-four and three hours into a twelve-hour shift as a med student on surgery rotation. The kind of shift you survive with black coffee and adrenaline and the quiet thrill of being allowed to stand near the interesting stuff.

We were halfway through morning rounds when my stomach twisted.

Not much, at first. Just enough to make me press a palm low against my abdomen and breathe a little deeper.

“You okay?” my attending, Dr. Shah, murmured out of the corner of his mouth while the intern presented.

“Fine,” I lied. “Just need to grab water later.”

By mid-morning, the pain had moved from “annoying” to “concerning.”

It drilled into my right lower quadrant, sharp and mean, radiating outward in waves that made the edges of my vision pulse.

I’d seen enough appendicitis cases to recognize the signs.

I had half a dozen excuses lined up in my head.

Bad sushi. Gas. Cramps.

I didn’t use any of them.

“Dr. Shah,” I said, intercepting him as he stepped out of a patient’s room. “I… think I need to get checked.”

He looked at me then.

Really looked.

Sweat dampened the back of my scrubs despite the cool hallway. My grip on my tablet was white-knuckled.

“How long?” he asked.

“Couple hours,” I said. “It was dull at first. Now it’s… not.”

He didn’t waste time asking why I hadn’t said anything sooner. He just grabbed a nurse.

“Page ED,” he said. “Tell them I’m sending down a med student, possible appy. Get her into a bay, labs, imaging. Put a rush on it.”

“You don’t have to—” I started.

He cut me off. “You’re not useful to me if you perforate on rounds,” he said. “Go.”

In the ED, they moved quickly once they realized my story matched my exam. Guarding. Rebound tenderness. White count climbing.

The CT scan just put a picture to what we already knew: my appendix was pissed.

“We’ll get you into the OR within the hour,” the ED doc said. “Good timing. Another couple hours and we’d be looking at rupture.”

I nodded. The pain had settled into something constant and grinding now, like a hot fist twisting in my gut.

“Do you have someone you want us to call?” the nurse asked, prepping my IV. “Family? Partner?”

“My mom,” I said.

It was automatic.

I gave them her number.

They gave me fentanyl.

The world blurred at the edges.

I drifted.

Something warm touched my hand.

“Nora.” My mother’s voice.

I opened my eyes.

She stood at the foot of the stretcher, arms crossed, handbag dangling from one wrist. She was dressed to the nines. Hair sprayed into perfection. Makeup sharp. The kind of dress you wear when a photographer will be present.

“Hey,” I managed. “Nice… dress.”

She huffed. “Don’t you start,” she said. “Your sister’s losing her mind.”

It took me a second to remember.

The wedding.

Of course.

I’d been up late the night before, hanging tiny white lights in the backyard of the rented venue, tying ribbons on mason jars, folding napkins into shapes Claire had found on Pinterest. I’d planned to grab three hours of sleep before my shift.

I’d planned to finish by noon and head straight to the bridal suite.

None of that included my appendix going rogue.

“The doctor said they’re doing surgery,” Mom continued. “How long?”

“Soon,” I said. “They said the appendix is angry. Needs to come out. Shouldn’t be long. It’s laparoscopic these days. Out by tonight. Probably.”

I was babbling. Fever and narcotics.

Mom’s mouth pinched.

“Can you postpone it?” she asked.

I blinked.

“What?”

“Postpone,” she repeated. “Push it a few hours. The ceremony’s at two. Pictures start at noon. We need you in the photos, Nora. You’re maid of honor. I can’t explain you not being there.”

Pain flared, sharp enough to make my breath hitch.

“Mom,” I said, careful. “They just said… hours matter. They don’t want it to rupture.”

She sighed, like I was being difficult on purpose.

“You’re a med student,” she said. “Not a child. You know how doctors are. They exaggerate. It’s not like you’re dying.”

The edges of the world wavered again.

“I—”

“I told Claire you’d be there,” she continued, talking over me. “She’s already stressed. If she hears you’re in surgery, she’ll freak out. Her makeup will be ruined. The photos will be ruined. This is her day, Nora. She’s been planning this since she was six. You can get your little routine surgery done after.”

My little routine surgery.

I stared at her.

The monitor beside my head beeped, oblivious.

“It’s not… like rescheduling a haircut,” I said. “They literally just said if we wait, it could perforate.”

“‘We,’” Mom repeated, as if I’d said something silly. “You’re not the surgeon. You’re the patient. You can say no.”

“Why would I say no to… not dying of sepsis?” I asked, words slurring a bit around the edges.

She pressed her lips together.

“You’re being dramatic,” she said. “You always do this. Make everything about you. That’s why you go into these jobs—so people have to pay attention.”

It was like being punched in a part of me that had nothing to do with my abdomen.

I’d spent the last eight years proving myself in pre-med, then medical school, not because I wanted attention but because I loved the work. The complexity. The challenge. The quiet, sacred miracle of taking a broken body into your hands and putting it back together.

But in that moment, flat on my back in an ED bay with my hospital bracelet cutting into my wrist, all my mother saw was a bad scheduling conflict.

“Your sister’s big day matters more than your surgery,” she said finally.

Calm. Certain.

Like we were talking about dress fittings instead of internal organs.

I swallowed.

Like a good daughter. Like a good soldier.

“Okay,” I said. “Talk to the surgeon.”

Her shoulders relaxed.

“Thank you,” she said, patting my ankle like I was a dog that had finally obeyed. “I knew you’d understand.”

She swept out, heels clicking on the linoleum.

The nurse came back in a few minutes later, frowning.

“Your mother’s asking to delay,” she said. “She says the family needs you at a wedding.”

I nodded once, because nodding hurt less than talking.

“Do you want to delay?” the nurse asked. Her eyes were sharp. Too sharp. She knew the answer already. She was asking for chart purposes.

“I…” A wave of pain rolled through me like fire. I gritted my teeth until it passed. “I don’t want it to rupture.”

“That’s not what I asked,” she said gently. “Do you want to proceed now?”

The ED doc appeared behind her, expression tight.

“We’re recommending immediate surgery,” he said. “I can sign the consent, but if your family is pushing—”

“My mother thinks it can wait,” I said. “My sister’s… wedding.”

He exchanged a look with the nurse.

“I can document that we strongly advised against delay,” he said. “But if you say ‘yes, wait,’ I’m… bound.”

They couldn’t make me.

Just like Mom couldn’t sign consent for me.

It was my call.

My life.

My body.

Every lecture I’d ever heard about autonomy and informed consent echoed in my head. Every attending who’d said, “Just because the family wants something doesn’t mean it’s right for the patient.”

Funny how those lessons blurred when the family was your own.

Pain clawed up my side again. I squeezed my eyes shut.

“Can you…” I gasped. “Give me… thirty minutes?”

The doctor hesitated. “We’re already cutting it close,” he said. “But if we move you to the top of the next block, I can give you forty-five at most.”

“Okay,” I said. “Forty-five. I… need to make a call.”

He nodded, unwilling but resigned.

“We’ll check vitals in fifteen,” the nurse said. “But if your BP drops, we’re going. With or without your mother’s blessing.”

She squeezed my hand once before walking out.

When they left, the room felt larger and smaller at once.

I stared at the cracks in the ceiling. counted them. Twelve. Fourteen. Nineteen.

My phone buzzed on the tray beside me.

Claire, according to the caller ID.

I answered.

“Don’t you dare do this to me,” she snapped before I could say hello.

“Hi,” I said weakly. “Nice to hear—”

“I told Mom not to tell you,” she barreled on. “Because I knew you’d find a way to make this about you. And now she says you’re in the hospital and you can’t come and you’re having some… elective surgery?”

“It’s not elective,” I said. “My appendix—”

“I don’t care what it is,” she cut in. “Do you have any idea how stressed I am? The florist messed up the peonies. The caterer is late. The photographer wants you here for pre-ceremony shots. And now you’re threatening to bail? On my wedding?”

“I’m not threatening,” I said. “I’m… I might be septic soon if we don’t—”

“You’re always like this,” she said. “You think because you’re in med school everyone has to rearrange everything. Newsflash, Nora: being a doctor doesn’t make you more important than everyone else. Everyone has life events. Mine matters today.”

I closed my eyes.

Pain spiked again, blurring the edges of her words.

“I never said I was more important,” I managed. “I just… don’t want to die on your cake table.”

“God, you’re so dramatic,” she said. “You sound like Mom. Just postpone it a few hours. Or tomorrow. Normal people don’t schedule surgery on their sister’s wedding day.”

“I didn’t schedule it,” I whispered. “My body did.”

She scoffed.

“This is exactly why Dad says you’re selfish,” she said. “You can never just… show up for us. You always have to be special.”

She hung up.

The dial tone buzzed in my ear.

I put the phone down.

Counted more cracks.

Legally, the decision was mine. Ethically, medically, every training I’d ever had screamed at me that delay was a terrible idea.

But somewhere, deep and rotten, the voice that had been drilled into me since childhood whispered: Don’t ruin things. Don’t be a burden. Don’t make a scene.

I lasted twenty minutes.

At minute twenty-one, my blood pressure dropped.

The monitors squealed.

The ED doc came back in, all business. “That’s it,” he said. “We’re going. Consent stays as is. You nodded when I said ‘as soon as possible.’ That’s enough for me.”

They wheeled me down the hall.

Anesthesia blurred the world into soft edges.

I woke up hours later, throat sore, abdomen a foreign landscape of pain.

“Appendix ruptured on the table,” Dr. Shah said, hovering over me. “We washed you out, but it was messy. You’re lucky we didn’t wait longer.”

Lucky.

Luck tasted like bile.

Mom wasn’t there.

Neither was Claire.

They had a reception to host.

Dad showed up the next day.

He stood at the foot of my bed, hands in his pockets, suit a little wrinkled.

“How was the wedding?” I croaked.

“Beautiful,” he said. “Shame you missed it.”

“I didn’t have much choice,” I said.

He shrugged.

“Your timing’s always been unfortunate,” he replied.

Then he left.

And that was that.

Lying in that bed, fever simmering, abdomen burning, I learned that love can be rationed. That loyalty can be conditional. That in my family, my pain was negotiable, but my sister’s happiness wasn’t.

It didn’t flip a switch in me that day.

It turned a dial.

Slowly.

Steadily.

Away from needing their approval.

Toward needing my own.

Part 3

You don’t go into surgery because you like control.

You go into surgery because you respect it.

Because you know, intimately, how thin the line is between order and chaos, between a clean incision and a bleeder you can’t quite find. You understand that nothing is guaranteed. You worship preparation. You bow to anatomy. You make peace with pressure.

And if you’re me, you also go into surgery because you like being needed.

In an OR, your value is undeniable.

You’re not the backup dancer. You’re the one holding the knife.

Residency was a long blur of sleepless nights, bad coffee, and adrenaline. The hospital became my whole world. Compared to appendicitis and wedding days, it was simple in its brutality.

Patients came broken.

We tried to fix them.

Sometimes we did.

Sometimes we didn’t.

There was grief. There was triumph. There were jokes that wouldn’t make sense anywhere else. There was the quiet, holy hush when a team worked as one unit, no ego, just skill.

I thrived.

I thought, stupidly, that if I became good enough, my family would see me differently.

Not special, exactly.

Just… valuable.

“What’s the point, really?” Mom said once during my second year, swirling wine in her glass while I iced my hands after a sixteen-hour vascular case. “You’re never home, you’re always tired, and for what? Claire makes more than you just helping Finn with contracts. And she doesn’t have to wipe blood off her shoes.”

Finn, her husband, owned a consultancy firm that did something with logistics and tax shelters. The details bored me. Claire loved it. She loved the clients, the dinners, the way people in suits leaned in when she spoke.

She loved being the sun.

I was a reliable lamp in a back hallway.

“I like my job, Mom,” I said. “That’s the point.”

“You’ve always been difficult that way,” she replied. “Claire knows how to make her life easier. You always pick the hardest road possible.”

Dad chimed in from behind his newspaper. “Hard work is fine,” he said. “As long as it leads somewhere.”

“Somewhere like… chief of surgery?” I said, half-joking.

He snorted. “Those jobs go to people who play the game,” he said. “You don’t know how.”

I didn’t answer.

I just filed the remark away.

Claire, meanwhile, floated.

She called me often—for help.

“Hey, genius,” she’d say, breezy. “Can you look over this application for me? It’s for that hospital board position Finn thinks I’d be great for.”

“I’m on call,” I’d say, scrubbing in.

“It’s not due for a week,” she’d reply. “You can do it when you’re bored.”

She asked me to review her statements of purpose, her personal essays.

“I just want to sound smart,” she’d say. “Like you do.”

I edited. Tweaked wording. Tightened paragraphs. Gave feedback.

It felt like being the older sister I thought I was supposed to be.

I didn’t realize she was learning my voice.

Not her own.

Mine.

The first real crack in that illusion appeared in my fifth year of residency.

I was in the residents’ lounge, microwaving a day-old piece of pizza, when an email pinged.

SUBJECT: Congratulations on Your Publication Acceptance

I frowned. I wasn’t expecting any news. My last paper had been rejected with suggestions to resubmit.

I opened it.

Dear Dr. Lennox,

We’re pleased to inform you that your article “Comparative Outcomes in Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve Replacement” has been accepted for publication…

My eyes skimmed the rest. I didn’t recognize the title. I hadn’t written on aortic valves. I was a general surgery resident. Cardio was Claire’s obsession.

At the bottom of the email was a PDF. Manuscript draft.

I clicked.

The first line was hers.

The second line was mine.

Not literally, but stylistically. Sentence structure. Word choice. The way data was introduced.

I scrolled.

Halfway down, a paragraph jumped out at me.

I knew that paragraph.

Because I’d written it years ago, in an essay for a surgical ethics elective.

Not word-for-word. But close.

Too close.

I scrolled to the byline.

DR. CLAIRE LENNOX–MILLS

DEPARTMENT OF CARDIOTHORACIC SURGERY

No co-authors.

My cursor hovered.

I forwarded the email to Claire with a single question mark.

She replied in minutes.

Oops! she wrote. That journal’s auto-email must’ve pulled your contact from my old draft template. You know how these systems are.

Another ping.

New email.

Hey, hope you don’t mind—I used that ethics paragraph we worked on together. It just fit so well. Thought we were on the same page about this stuff.

The nausea that rolled through me had nothing to do with recirculated pizza.

We worked on together.

She’d taken my words, repackaged them, and called it collaboration.

In isolation, it was a small theft.

A paragraph.

An email.

A glitch.

But it hit me like the CT scan had years ago.

It changed how I read the images.

I started looking backward.

At the hospital board statement she’d asked me to glance at. At the fellowship essay she’d wanted “quick feedback” on. At the sample recommendation letter she’d drafted “for structure” using an old one I’d written for a colleague.

At first, all I saw was familiarity.

Then I saw fingerprints.

Mine.

In my spare minutes, I pulled up her publicly available bio.

Board member, St. Theresa’s Foundation. Clinical advisor, Metro Health.

Publications. Presentations.

I clicked through them.

The phrases I’d thought were just “family jokes” showed up in her professional statements. The research questions I’d been mulling aloud over drinks turned up in her talks. The connections I’d introduced her to had been built into ladders she’d climbed without once looking down.

At first I thought it was just… me being paranoid.

We’d grown up together, after all. Of course we’d sound alike sometimes. Of course we’d move in similar circles.

Then she texted me.

Guess what?? Got the Simmons Fellowship!

The Simmons Fellowship.

The one at Ridgefield Medical Center. The one with the intensive minimally invasive training. The one my attending had suggested I apply for. The one I’d quietly dreamed about since my second year.

I pasted a smiley face into the chat.

Congratulations!

I sat there looking at the screen.

My own application had been rejected months earlier with a vague, “We selected candidates whose profiles more closely aligned with our program’s vision.”

There were only two positions.

It wasn’t impossible we’d both applied.

It wasn’t impossible she’d been chosen over me.

I told myself it didn’t matter.

We were different specialists. Different paths. Different lives.

Then, one night, an email pinged into my inbox from the Simmons Fellowship coordinator.

It was short.

Dear Dr. Lennox,

Thank you again for your interest in our program and for your professionalism during the application process. I wanted to clarify a small administrative question—

In your recommendation for Dr. Lennox–Mills, you mentioned…

I stopped reading.

I hadn’t written a recommendation for Claire for Simmons.

I hadn’t been asked.

I scrolled down.

Attached was a PDF.

LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION – DR. CLAIRE LENNOX–MILLS

FROM: DR. NORA LENNOX

The letter was glowing.

Claire is one of the most promising surgeons of her generation. I have personally trained her in multiple advanced procedures and have no doubt she will be an asset to your program…

My name was at the bottom.

My signature.

An old digital copy she’d had from a previous letter I’d written for someone else, edited and reattached.

The coordinator’s question was minor—clarifying a procedure I’d supposedly observed Claire perform.

My fingers shook on the keyboard.

I picked up the phone and called the number at the bottom of the email.

The coordinator answered.

“Dr. Lennox?” she said. “Bridget here. Sorry if the email was confusing. I just wanted to—”

“I didn’t write that letter,” I said.

Silence.

“I’m sorry?” she said.

“I did not write that recommendation,” I repeated. “I didn’t endorse her application. That letter was submitted without my knowledge or consent. The signature was… repurposed.”

“Oh,” she said. Then, slowly, “Oh.”

I could almost hear the gears turning on her end.

“I see,” she said. “That’s… concerning.”

Understatement of the year.

I could have exploded right then.

Called Claire. Screamed. Told Mom. Told Dad. Told every relative who’d ever said, “You should help your sister, she just wants to be like you.”

Instead, I felt something else settle in.

Not rage.

Not heartbreak.

Clarity.

I replayed the birthday, the surgery, the wedding, the board positions. I replayed Mom’s words. Dad’s. Claire’s.

You’re being dramatic.

You always make things about you.

Your sister’s day matters more than your surgery.

It was a pattern.

I just hadn’t been standing far enough back to see the shape of it.

“I’m going to forward you some documentation,” I told the coordinator. “Original letters with date stamps. Email chains. Anything that shows what I have—and haven’t—endorsed.”

“Yes,” she said. “Please do. We have an internal process for this kind of… discrepancy.”

We hung up.

I opened a new email.

Attached everything.

Then I sat back in my chair.

I didn’t cry.

I didn’t call anyone.

But a door in me, the one that had always been slightly ajar for family, for “but she’s your sister,” swung shut.

Not locked.

Just… closed.

Later, I got a terse message from Claire.

You told Simmons I faked your letter??? Wtf, Nora.

I stared at it.

You faked my letter, I typed. I just told them the truth.

She didn’t reply.

The fallout from Simmons was quiet.

They didn’t rescind her fellowship—too late, too political—but her file now had a note. The kind that follows you even if everyone pretends it doesn’t.

I knew because a year later, when I interviewed at Metro General, the department head asked a gentle, circling question.

“Your sister had some… hiccups early in her career,” he said. “You two close?”

“Not particularly,” I said.

He nodded, satisfied.

At Metro, I started over.

New hospital, new hierarchy, same game.

Except this time, I didn’t just play medicine.

I played politics.

Not the slimy kind. Not the gossip. The structural kind. The committees everyone rolled their eyes at. Quality Assurance. Ethics. Morbidity & Mortality review. The places where decisions got made before anyone knew there was a decision to be made.

I chaired the Clinical Documentation Committee—twice.

I rewrote protocols.

I made sure every case I touched was clean, every chart impeccable.

I built alliances with people who didn’t need their brilliance advertised. The quiet administrators, the risk managers, the compliance officers who were always the first scapegoats when something went wrong.

I published.

Not in the flashiest journals. Not with my name in lights. But consistently. Ethically. Thoroughly.

I said no to things that would have looked good on paper but smelled like shortcuts.

Other people said yes.

At home, family gatherings got perfunctory.

Claire strutted in with new achievements—chief of cardio at a mid-sized hospital, keynote at some conference, panelist on a public health podcast. Mom gushed. Dad nodded. Everyone clapped.

“How’s work, Nora?” Mom would ask as an afterthought.

“Good,” I’d say.

“You should talk to Claire,” she’d reply. “She’s doing some amazing things. You could learn a lot from her.”

Claire always smiled.

“I just want to be like you, big sis,” she’d say, eyes bright. “You set the bar. I just… found a faster way to get over it.”

I said nothing.

Silence is not consent.

Sometimes, it’s reconnaissance.

By the time Metro’s Chief of Surgery announced his retirement, my name was on three separate internal “short lists.”

I wasn’t the most senior. I wasn’t the flashiest. But I was the one every department head described the same way:

Steady.

Thorough.

Fair.

The board interviewed me.

They asked about my vision, my leadership style, my plans for reducing surgical site infections, improving mortality metrics, recruiting talent.

They did not ask about my family.

I didn’t volunteer.

When they offered me the job, I felt that small internal click again.

Not of revenge.

Of alignment.

Months later, when a CV crossed my desk for an open cardiothoracic attending position, I almost laughed.

DR. CLAIRE LENNOX–MILLS

On paper, she was perfect.

Strong productivity. High case volume. Leadership roles.

A minor note about “documentation concerns” from a previous post.

No overt red flags.

Metro’s HR had flagged her as a “top-tier candidate.”

“Strong pedigree,” the recruiter said. “Would be a get.”

I stared at the file.

I could have killed it silently.

One note in the system. One “not a fit.”

Instead, I forwarded her to the selection committee.

With a simple note:

Proceed with standard vetting. Full reference check.

Standard.

Full.

No shortcuts.

If she got through that?

Then we’d see.

Part 4

“Welcome, everyone,” I said.

Conference Room B hummed with low conversation as department heads settled into their seats. Legal and HR perched at the back, laptops open. The Chief Medical Officer sat to my right, hands folded, watching.

On the projection screen behind me, the hospital logo glowed. Under it: CLINICAL AUDIT FINDINGS – Q2.

I’d run half a dozen of these presentations in the past year. Infection control. Blood usage. Peer review statistics.

Today’s was… different.

“Let’s try to keep this under an hour,” I added. “People actually need OR time today.”

A ripple of chuckles.

I flicked through the first few slides quickly. No one needed their hand held through the boring parts. Some metrics were up, some down. Action plans were in place.

Then I clicked to the section that mattered.

“Authorship discrepancies,” I said. “Across multiple departments.”

The room shifted.

People leaned in.

“We ran a routine check,” I continued, “cross-referencing internal quality improvement projects and published work tied to Metro. What we found was concerning. There are several cases where internal drafts list one set of authors, and published versions list another. No internal documentation of consent, no formal transfers of authorship.”

I clicked.

Three examples flashed up. Names. Dates. Redacted case details.

Murmurs rose.

“That’s… not great,” someone muttered.

“In most cases,” I said, “it appears to be benign sloppiness. Trainees doing grunt work and attendings attaching their names. Not ideal, but fixable with education and a formal process.”

A soft exhale of relief.

“In a few cases,” I added, “it looks less benign.”

Slide.

“Some of you will recognize this project,” I said. “It started here as a multi-disciplinary initiative. Residents, nursing leadership, anesthesia. The internal version lists five authors.”

Slide.

“The published version lists three,” I said. “Two attendings and a ‘consultant’ who did not appear on any internal drafts, did not submit any documented work product, and whose contributions we could not verify beyond… suggestions in meetings.”

On the screen, in neat black letters, was a name.

DR. CLAIRE LENNOX–MILLS

I didn’t look at her.

I didn’t need to.

I could feel the oxygen leave her side of the room.

“Dr. Lennox–Mills is hardly the only person who’s had… enthusiastic self-promotion issues,” I said, keeping my voice neutral. “But her pattern is unusually consistent. Across institutions.”

A hand shot up halfway down the table.

Cardiology.

“I’m sorry,” Dr. Khan said. “Pattern?”

“Yes,” I said. “We requested records from her previous hospitals as part of our standard credentialing process. The volume of retracted or disputed authorship claims linked to her name is… non-trivial.”

I clicked.

A list appeared. Reds and yellows highlighting retractions, corrections, “expressions of concern.”

Legal shifted in their seats.

“Additionally,” I continued, “we have documented instances of recommendation letters submitted under other physicians’ names without their knowledge. One such case was investigated by the Simmons Fellowship program.”

I didn’t have to say whose.

The CMO cleared his throat.

“Dr. Lennox–Mills,” he said, finally turning toward her, “is there anything you’d like to say at this point?”

All eyes swung to her.

Claire sat very straight in her chair, fingers white-knuckled on her portfolio.

“This feels like a targeted attack,” she said. Her voice trembled, but she tried to inject it with outrage. “I was invited here. Recruited. And now… what? Dragged into some audit gotcha game? You’re making a mountain out of clerical misunderstandings and politics.”

“Clerical,” I repeated. “Is that what you’d call signing my name to a letter I didn’t write?”

She flinched.

“You’re exaggerating,” she snapped. “You always have.”

There it was.

The old script.

“Nora, perhaps we should—” she started.

I lifted a finger.

Just one.

The same way I would if an intern started cutting before I’d finished outlining the anatomy.

“Let me finish,” I said.

The room went very still.

No one had ever seen us like this.

Most of them didn’t even know we were related.

“Metro’s responsibility,” I said, addressing the room again, “is first to our patients. Second to our staff. Third to our reputation. In that order. Allowing a pattern of misattribution, fraudulent documentation, and exploitation of trainees to go unaddressed puts all three at risk.”

“This is overblown,” Claire said. Her voice was higher now, clawing for footing. “Everyone does this. Everyone uses their networks. You think any of you got here purely on merit? Grow up.”

“Everyone doesn’t forge signatures,” I said.

Her face went white.

“You can’t prove—” she began.

“Metadata is a wonderful thing,” I said calmly. “So are server logs. IP addresses. Timelines. When you submit a letter from someone’s account at 3 a.m. while they’re scrubbed into an emergency colectomy, it leaves footprints.”

A murmur.

The Chief of Anesthesia frowned. “Wait, that was… you?” he asked, looking between us. “We heard rumors at Simmons, but…”

Claire’s composure cracked.

“Are you seriously doing this?” she hissed. “Here? Now? In front of everyone? You’re my sister.”

“Yes,” I said simply. “And right now, I’m also your chief.”

The word landed like a scalpel.

Chief.

Not big sis.

Chief.

“This doesn’t have to be… career-ending,” the HR director interjected, sliding into the conversation with trained neutrality. “But it does require remediation. Formal ethics counseling. Supervision. Restrictions on independent research and mentoring for a period to be determined.”

“In other words,” Claire spat, “a leash.”

“In other words,” I said, “consequences.”

Her eyes filled with tears.

Real ones, I thought.

Not the kind she’d summoned for dramatic effect during childhood tantrums.

“You never forgave me,” she whispered. “For that stupid day in the hospital. For the wedding. For Mom choosing me. This is about that, isn’t it?”

The room faded for a second.

It was like we’d been pulled through a trapdoor back to that ED bay. To that ceiling. To Mom’s voice.

Your sister’s big day matters more than your surgery.

“Yes,” I said.

Gasps.

Claire’s mouth opened triumphantly. “So you admit—”

“Yes,” I continued, overriding her. “That was the day I realized you’d do anything to stay at the center of the story. Even if it meant letting someone else bleed off-stage. That’s when I started watching you more closely than I watched my own incision healing.”

Her face crumpled.

“I loved you,” she said. “I still do.”

“I believe you,” I said. “In your way. But love without respect isn’t enough. Not here. Not when my job is to make sure no one uses my hospital the way you’ve used my life.”

Silence.

The CMO leaned forward.

“Dr. Lennox–Mills,” he said gently, “we’re placing you on administrative leave, effective immediately. We’ll complete our investigation and outline next steps. You have the right to respond, to bring counsel, to appeal. But for now, you will not be practicing unsupervised at Metro. Do you understand?”

Her chin lifted.

“This is her revenge,” she said. “Don’t think she’s noble. She’s been waiting for this.”

“Actually,” I said, gathering my papers, “I’ve been avoiding this. For ten years. Because I knew what it would do to Mom. To you. To whatever was left of ‘family.’”

I looked around the table.

“But when it became clear that you weren’t just borrowing my words anymore—that you were using residents’ work as your springboard, that you were leaving students behind in your wake—I stopped caring about the fallout and started caring more about the damage.”

I met her eyes.

“You taught me a lesson that day in the hospital,” I said. “You and Mom and Dad. You showed me my place in the family. Today, I’m teaching you one in return. This is your place here: subject to the same rules as everyone else.”

Her breath hitched.

“Please,” she whispered.

I remembered lying in that bed, begging in my head for someone to choose me. To prioritize my safety over a photo op.

No one had.

“I won’t stop you from getting help,” I said. “But I will stop you from hurting people on my watch.”

HR stood.

“Dr. Lennox–Mills,” she said, voice soft but firm. “Let’s step outside.”

Claire rose on shaky legs.

For a second, she looked smaller than I’d ever seen her. Not the center of the story. Not the sun. Just a woman whose shortcuts had finally run out.

As she reached the door, she stopped.

“Nora,” she said without turning around. “If you’d just… forgiven me, none of this would’ve happened.”

I almost laughed.

“If you’d ever said ‘I’m sorry’ and meant it,” I replied, “we might not be here either.”

She left.

The door closed behind her with a soft click.

I stood there, hands steady on the table.

The CMO exhaled.

“Well,” he said. “That was… something.”

“Necessary,” I said.

He nodded.

“Yes,” he replied. “It was.”

Part 5

Moms know when you’ve done something unforgivable.

Not because of cosmic mother-daughter telepathy, but because the grapevine is faster than any data network.

Three hours after the meeting, my phone rang.

I recognized the number.

I almost let it go to voicemail.

Almost.

“Hi, Mom,” I said.

“You ruined her,” she said without preamble. Her voice was tight, the way it had been when the florist got the peonies wrong. “You humiliated your sister. Again. Does that make you happy?”

“No,” I said. “It makes me tired.”

“How could you?” she demanded. “In front of her colleagues? Stripping her down like that? You always were jealous, but this—”

“Stop,” I said quietly.

She did.

She’d never heard me say it like that.

“When I was twenty-four,” I continued, “lying in an ED with my appendix rupturing and a fever spiking, you told me my sister’s big day mattered more than my surgery. You told me I was selfish for not postponing. You told me I was dramatic when I said I might die.”

“That’s not fair,” she said, but the conviction in her voice had worn thin.

“It’s accurate,” I said. “That day, you taught me exactly where I ranked. You made a choice. I’ve spent a decade pretending I didn’t know that, because it was easier to blame myself. To think if I just did more, achieved more, you’d… see me.”

“You know that’s not true,” she protested. “We were under stress, and weddings are—”

“You chose her,” I said. “And I lived anyway. So I chose me. I chose my patients. I chose the interns and residents and nurses who don’t have the luxury of a chief who looks the other way when someone with a pretty CV cheats.”

“She’s your sister,” Mom said, as if invoking a spell.

“And I am my own,” I countered. “And my own chief. Claire’s choices are hers. So are her consequences.”

“She’s devastated,” Mom whispered. “She said you’ve been plotting this. That you held onto resentment and waited to strike. That you’re punishing her for my mistakes.”

“That sounds like her,” I said. “Blame flows downhill in that world.”

“Is she wrong?” Mom asked.

I thought about it.

“I didn’t orchestrate her forging signatures,” I said. “I didn’t tell her to plagiarize. I didn’t encourage her to climb over trainees. I just stopped cushioning her landings. The ground feels harder when you’re used to mattresses.”

“You’re cruel,” Mom said.

“I’m fair,” I replied. “For the first time in our family, maybe.”

Her breath hitched.

“How can you talk to me like this?” she whispered.

“Because I’m done pretending,” I said. “You taught me how to stay silent. Medical school taught me how to speak. I’m choosing the second on purpose.”

“What do you want from me?” she asked, sounding suddenly very old.

“Nothing,” I said, and meant it.

Silence stretched between us like the sterile drape over an open abdomen.

“I loved you both,” she said finally. “I did my best.”

“I believe you,” I said. “In your framework, you did. That doesn’t change what happened. And it doesn’t mean I have to keep living inside that framework.”

“You’ll regret this,” she said.

“Maybe,” I said. “But I regret letting my appendix rupture to keep the peace more.”

She hung up.

Later that week, Eli—now nineteen, home from his sophomore year of college—found me at the kitchen table, staring at my badge.

He picked it up, weighed it in his hand.

“Chief,” he said. “Sounds like a superhero. Or a villain. Depends on who you ask.”

“Today?” I said. “Definitely a villain.”

“Claire?” he asked.

“Claire,” I said.

He sat down across from me.

“You know,” he said, “if you’d let her keep doing what she was doing, one of her residents might have turned into a smaller version of her. Or quit. Or burned out. Or thought that’s just how you succeed in medicine.”

“I know,” I said.

“She’ll hate you for a while,” he said. “Maybe forever.”

“I know that too,” I said.

“You can live with that?” he asked.

I thought back to that ED ceiling. To the cracks. To the way the room had spun while my mother talked about corsages and photographers.

“Yes,” I said. “I can live with that.”

I could live with a lot worse.

I’d already survived it.

Eli nodded.

“I saw Tyler the other day,” he said suddenly.

My head snapped up. “Where?”

“Campus,” he said. “He’s doing some public health degree now. We had coffee.”

Despite myself, I raised an eyebrow.

“It was… weird,” Eli admitted. “But good. He’s different. Therapy’ll do that.”

“Did he apologize?” I asked.

“He did,” Eli said. “Again. And better. He didn’t say ‘if I hurt you.’ He said ‘when I hurt you.’ Which my therapist says is the correct pronoun.”

“Smart therapist,” I echoed my own words from years before.

“He asked about you,” Eli added.

“Oh?” I said.

“He said, ‘Is your mom still terrifying?’” Eli said, smirking. “I said, ‘More now that she runs a department.’ He laughed and said, ‘Good.’”

Something in my chest loosened.

“He said, ‘Tell her thanks,’” Eli continued. “For the board meeting. For the fallout. He said it broke their house, but in a good way.”

“Bones set straight,” I murmured.

“Huh?” Eli asked.

“Nothing,” I said. “Inside joke.”

Eli looked at my badge again.

“You know what I like most about this?” he asked.

“The paycheck?” I suggested.

He snorted. “Sure. But also… when you walk into a room now, no one can say your pain matters less than someone else’s party.”

My throat tightened.

“This isn’t about payback,” I said.

“I know,” he replied. “It’s about you finally being in a place where your voice carries as far as your responsibility does. That’s… right.”

He put the badge back down gently.

“You earned it,” he said. “Without stealing it. You didn’t put anyone’s name on anything it didn’t belong on. You did this the hard way.”

“Is there any other way?” I asked.

He grinned. “For some people, apparently,” he said. “For you? No.”

He stood.

“I’m proud of you, Mom,” he said over his shoulder. “Even if Grandma isn’t right now.”

“That makes one of you,” I said.

“Two,” he corrected. “Tyler kind of is. He just won’t admit it to your face yet.”

I laughed, surprising myself.

Later, in the quiet of my bedroom, I sat on the edge of the bed and stared at the badge hanging from my coat on the chair.

Chief of Surgery.

It didn’t feel like a throne.

It felt like a responsibility I’d chosen.

To be the person I’d needed when I was twenty-four and powerless.

Not just for my patients.

For my staff.

For every resident who thought they had to swallow harm to survive.

For every younger sibling who thought their pain was negotiable.

Years from now, people will forget the details of that conference room. Of the audit. Of Claire’s face when the evidence stacked up higher than her defenses.

They won’t forget the culture it created.

The memo that went out afterward. The mandatory authorship training. The new policy that made forging someone’s name not just unethical but practically impossible.

They’ll just know that at Metro, you get credit for your work. That if you speak up when something’s wrong, someone listens.

They won’t know it started with an appendix that ruptured because a wedding mattered more than surgery.

I will.

I don’t tell anyone that story anymore unless I trust them with the person I was back then.

The girl staring at ceiling cracks, learning that love could be conditional.

The woman adjusting a badge clip, feeling it snap into place, realizing that some conditions you do get to set yourself.

The next morning, I walked back into the hospital.

Past the ORs. Past Conference Room B. Past the lobby where volunteers greeted visitors who had no idea of the quiet wars that had been fought in these walls.

Someone called my name.

“Dr. Lennox!”

I turned.

A second-year resident ran up, breathless.

“Sorry,” she said. “The family in 8B is asking if you can talk to them about the risks of the surgery. They said they’ll only consent if you explain it.”

I smiled.

Family. Consent. Risk.

Full circle.

“Of course,” I said.

I adjusted my badge.

Metal on fabric.

Clean.

Final.

And for the first time, the weight on my chest didn’t feel like something I had to carry for someone else.

It felt like mine.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

MY PARENTS HANDED ME A DIRTY MOP IN FRONT OF 10 GUESTS. MY SISTER SNEERED, “YOU LIVE HERE FOR FREE

My parents handed me a dirty mop in front of 10 guests. My sister sneered, “You live here for free,…

HOA—Karen fined me $70 per home for ‘lawn shade’… it BACKFIRED!

HOA—Karen fined me $70 per home for “lawn shade”… it BACKFIRED! Part 1 The notice on my door was…

AT SUNDAY LUNCH, I ASKED CASUALLY, “DID YOU PICK UP MY PRESCRIPTION? THE DOCTOR SAID IT’S URGENT.”

At Sunday lunch, I asked casually, “Did you pick up my prescription? The doctor said it’s urgent.” my dad said…

AT THE BIRTHDAY PARTY, MY SON SHOWED UP WITH A BRUISE UNDER HIS EYE. MY SISTER’S SON SMIRKED AND

At the birthday party, my son showed up with a bruise under his eye. My sister’s son smirked and said,…

My Husband Watched Them Strip Me of My Seat—So I Walked Away and Destroyed Him Calmly

My Husband Watched Them Strip Me of My Seat—So I Walked Away and Destroyed Him Calmly Part 1 My…

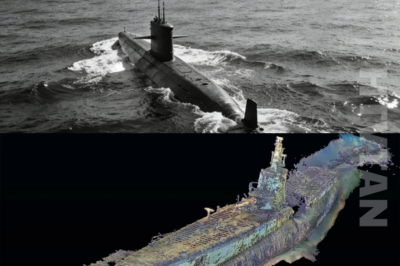

CH2. Why One U.S. Submarine Sank 7 Carriers in 6 Months — Japan Was Speechless

Why One U.S. Submarine Sank 7 Carriers in 6 Months — Japan Was Speechless The Pacific in early 1944 didn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load