Why Do You Hate Your Parents?

My parents kicked me out for getting a job and not being able to babysit anymore, then lied to the whole family when asked about it.

Part One

The fork knocked against the chipped plate once, twice—a dull little chime that sounded like someone politely tapping on the glass of my life to check for cracks. The sun hadn’t fully lifted over our stretch of Raleigh yet, and still the kitchen felt colder than a January wind. My mother stood at the stove turning eggs with the detached precision of someone paging through a manual. My father scrolled his phone as if he were rehearsing for a part he’d nailed a thousand times and could do in his sleep.

No “Good morning.”

No “How did you sleep, honey?”

Just silence with sharp edges.

You can always tell when your presence starts to feel like clutter in a room you used to belong in. You learn the weight of your footsteps, the breadth of your breath, the temperature of their patience.

I knew what was coming even before my mother spoke.

“We think it’s time you start standing on your own two feet,” she said, as if she were authorizing a return.

“I have been,” I said, softer than I meant to. “I’m not here for money, I’m just… between leases. The coffee shop—”

“You’re almost seventeen, Julia,” my father interrupted without looking up. “You’ve had plenty of time to figure things out.”

The stomach-drop was immediate, dizzying. It wasn’t about a lease. It wasn’t about a schedule. It was about me.

“You’re not married,” my sister called from the stairs, because of course she made an entrance for the line she’d been practicing. “No kids. Still here.” Kalista had a way of smiling that felt like someone shutting a drawer.

My mother stepped away from the stove. The old brown suitcase—the college one with the frayed handle and the little turtle sticker I’d plastered onto it sophomore year—skittered across the linoleum and bumped my chair.

“Fifteen minutes,” she said.

Not a conversation. Not a plan. A clock.

I stood. I didn’t beg. I didn’t argue. I didn’t ask for one more day. I went upstairs and, for the first time in a long time, let myself feel it: the heartbreak, the betrayal, the bright animal grief of understanding you might never know a life where your parents love you without strings.

I didn’t wipe the tears. I stuffed as many clothes into my backpack as physics allowed. Ten minutes later, they yelled for me to hurry up—as if we were late for something fun—and we drove to my cousin Megan’s. In the car, my father reminded me of how much my siblings loved me, or more specifically, how no one else could get them to stop crying like I could. My mother cried—not because she’d miss me, but because now they had to pay for a babysitter. I sat in the backseat with my backpack in my lap and questioned whether I was selfish, and then I reminded myself that selfish is the word people use on girls who dare to stop carrying their family on a schedule.

They dropped me off without a goodbye and drove away before the door had even fully closed behind me. When Megan opened it, her whole face lit, honestly surprised and honestly glad to see me. Kindness felt so unfamiliar it knocked the air out of me. I started crying before I could say hello.

“My love,” she cooed, “why don’t you just help them out a little longer?”

“Help?” I didn’t mean to shout, but the anger came out like a storm through a screen door. “I’ve missed parties, cut off friends, watched my grades slip so I could keep four kids fed and quiet and safe for two full years. Help?”

Shock rearranged her features. “Your parents told me you were being entitled. That you didn’t want to help, that you were home all day doing nothing.” Her mouth pinched. “They said you were… ungrateful.”

I told her everything. The late-night bottles, the tantrums, the way my mother would hold her phone up from the couch and tell me to Google how to get dried slime out of hair while I was trying to finish a lab report at the kitchen table. I told her about the “we love you, but” and the “you’re the only one who can” and the “this is what girls do.” She held me while the story came out wrong and messy and whole, then laid me on the guest bed like I was breakable and promised, “You’re safe here.”

I fell asleep. I woke to voices.

Megan almost never raised hers—it’s not in her nature. But in the next room her voice rose and kept rising. She isn’t a maid, she isn’t a mother, she isn’t a fix, she was saying, furious in a way I’d only ever seen her when a stray cat went missing from the apartment complex. I couldn’t make out every word, but I understood the shape of it. When the house went quiet again, she thought I was asleep and whispered to the lamp, “They had someone else lined up. This wasn’t about need. They just wanted the mess out of the living room.”

The shame at how deeply that sentence fit into me gave way to something else. Not rage. Not even courage. Clarity. If I couldn’t have better parents, I could at least have better boundaries. And if I couldn’t get an apology, I could get the truth onto a page.

Every family has a Barbara—the aunt who will turn inconvenient facts into holiday theatre. I typed a 1,400-word message until my thumbs trembled, sent it, and threw the phone to the end of the bed like it might bark. In the morning, my screen was a lit-up beehive. Aunt Barbara had forwarded the text to the whole family group chat because of course she had. Some relatives cluck-clucked about ungrateful teenagers; more of them than I expected took my side. Uncle Joseph wrote three paragraphs about how disgusted he was with his sister. Grandma Elizabeth posted a broken-heart emoji and then followed it with, I raised my children better than this. That one lodged somewhere under my ribs and set up a chair.

My father called. The volume made Megan’s eyes widen from across the room. I held the phone away from my ear while he told me I was dead to him and had humiliated them beyond repair and I was never to come home again. When he ran out of breath, my mother took the phone and spoke in a voice so frosted I could see it. “You’ve made your choice,” she said. “Don’t expect any support. Not for college, not for your phone bill. Nothing.”

“Can I get my stuff?” I asked, because grief makes you practical.

“You took what you needed,” she said. “Anything else we’ll donate if you don’t arrange pickup by the weekend.”

The call ended against my ear like a door quietly pushed shut.

Megan called in sick the next morning and drove me to the house while my parents were at work. I grabbed what I hadn’t been allowed time to take: laptop, books, clothes, the box of photos of my siblings that lived on my desk. Megan went into the office, because she’s a sneaky raccoon in a cardigan when she needs to be. Back at her apartment she placed a folder on my lap: my birth certificate, my social security card, and a credit card from the “for emergencies” drawer in the desk.

“You’re going to need these,” she said. “And that card? After five years of free childcare, they owe you toothpaste and black pants for work.”

I hated it. I also had fifty dollars to my name. We spent two hundred on basics: black t-shirts for the coffee shop, a prepaid phone, shampoo that didn’t smell like cloying summer, a bus pass.

The job was called The Daily Grind (because of course it was) and my manager, Jaime, had forearms like he actually lifted sacks of beans and patience like he had trained golden retrievers. I steamed milk wrong and apologized too much and still he told me, “You’re fine. You’re learning. We want you here.” Want was a new word. I carried it home like a croissant in a paper bag.

But the emergency card pinged someone’s phone. My mother called Megan and hurled the word theft into the receiver. Then she said the quiet part out loud: come home. The new babysitter had lasted a week. Four kids under ten is a lot when you aren’t related and have an actual schedule. Who knew.

“I’m not going back,” I said to Megan before she could ask. “I’ll pay the two hundred back. I’m not going back.”

“Good,” she said. “I told them that.”

At school the next day my hands shook through second-period algebra. I kept seeing cops walking into the coffee shop to arrest me for fraud in front of the espresso machine. My friend Casey tugged me outside to the courtyard and sat me down. When I told her everything she said, “That’s child neglect, Jules. You’re still a minor. They can’t just… do that.”

Her mother, Mrs. Thompson, was a lawyer. The three of us sat at their dining table after school with a glass of water in front of me and legal pads in front of her. She listened to my whole story without interrupting, then said, “Two paths—emancipation or CPS—but there’s a third: a relative petitions for temporary guardianship. You stay with someone safe. Your parents stop breathing down our necks. You finish the school year dying of only normal teenage things.”

Guardianship sounded like rescue with paperwork.

My grandparents showed up at Megan’s that evening with their serious faces on. “We want you to come live with us,” my grandmother said, and my first reaction was to protect them. “I don’t want to be a burden,” I said. “You’re not,” my grandfather said, which is a sentence you don’t understand you needed until it’s said to you.

My parents agreed immediately—on one condition: I had to visit and watch the kids one day a week. It wasn’t perfect. It was better than a suitcase and a bus stop.

At my grandparents’ place, the office became a bedroom overnight. Fresh curtains. A twin bed. A little bookshelf. My grandmother put a little vase of white daisies on the desk like the house wanted to nod at me. I slept like a person whose body had just been told a new law.

The first weekend I went back felt like walking onto a stage set to the wrong lighting cue. The kids came flying—Emma, ten, launched herself into my ribs; Alex, older by two years and already practicing the cool voice of teenage boys, stood closer than usual and said “Hey” like it meant more. My parents watched from the doorway, twin masks I didn’t recognize. I made sandwiches for the little ones and helped with math and pretended the clock on the microwave was untied shoes. My mother cornered me by the fridge.

“So you’re too good to live here,” she said. “But you’ll take handouts from your grandparents.”

“I’m trying to finish high school without sleeping under an overpass,” I said, sliding plates onto the table.

“You were never going to be homeless,” she snapped. “You dramatize everything.”

I didn’t point out who had put me on a curb with a backpack.

My grandparents paid off the emergency card without telling me until after they’d done it. “Every penny,” my grandfather said when I protested. “And we should tack interest on for all those nights you put kids to bed while your homework sat.” I promised to pay them back. He waved a hand like dirndls on a clothesline. “Pay us with Saturdays we get to see you without a phone in your hand apologizing.”

Mrs. Rodriguez, my English teacher, asked me to stay after class one Thursday and held an essay up between her fingers like it was something you could weigh. “This is one of the best pieces I’ve read from a student,” she said. “Have you considered scholarships?”

I didn’t tell her that scholarship had sounded like a sound you hear from the next room all my life while I scrubbed spaghetti off a high chair. She helped me draw a list anyway. I wrote at the kitchen table and in the corner booth at the coffee shop on my break and in Megan’s car between errands. Mrs. Rodriguez marked up my drafts with a green pen and wrote more here in the margins of the parts I kept trying to swallow.

My father found me writing one of the scholarship essays at their kitchen table during a weekend visit and read over my shoulder without asking. “College,” he scoffed. “What a waste of money. You should save up to get your own place instead of mooching.”

“I got into State,” I said. “Partial scholarship. I’m applying for more.”

“We’re not paying a penny,” he said, waiting to see if it would dent me.

“I know,” I said. “I’m applying for financial aid.”

He wanted to see me flinch. I didn’t.

Two weeks later an email arrived while I was doing chemistry homework at my grandparents’ table. National Merit—Finalist. The words were black pixels and electricity; the feeling was a dam cracking and realizing it’s not about water, it’s about weight finally having somewhere else to go. My grandmother sobbed. My grandfather did his old man whistle. Megan arrived with a grocery store cake and a knife that didn’t seem sharp enough for everything good happening at that table.

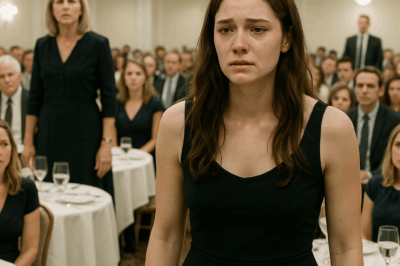

The interview was five people with excellent posture and two pitchers of water. I talked about tiny humans and big feelings and how I wanted to sit with kids while the house burned down and tell them they’re not made of kindling. I wore a navy blazer we bought on sale and shoes that didn’t slip on tile. When I walked out I didn’t know if I’d done enough; I just knew I’d told the truth as if it were a whole language.

Congratulations, the email said on a rainy Tuesday. Full tuition. Four years. Anywhere public in the state.

I called my mother because somewhere in me a small girl still needed to say look and have a face soften. “I guess all that studying paid off,” she said after a pause. She asked if I’d be moving away and then, so quietly I almost missed it, “The kids will miss you. We all will.” I took it. Sometimes you accept a small ribbon even if you needed a banner.

Graduation day handed us perfect June weather like an apology for a cruel winter. I wore a cap with Nevertheless, she persisted in glittery letters because subtlety is a privilege. My grandparents cried the way grandparents are supposed to cry. My siblings screamed when my name was said out loud into a microphone. My parents showed up. I kept waiting for the moment where the veneer peeled back, but it didn’t. Afterward my mother asked, Can we host a small party? and I stared at her like a person who’d spotted a glacier in Raleigh.

Aunt Barbara had apparently had a long conversation with my mother the week before. You could see the shape of it in the corners of the party. Balloons at the mailbox. A banner across the door. Food that probably had a list. A cake with my name spelled correctly. People who’d defended me when the group chat exploded stood in my parents’ dining room like witnesses to a miracle that had nothing to do with flour and butter. My parents gave me a gift in a small box. Inside: a key.

“To the house,” my mother said. “We want you to know you always have a home here.”

My father cleared his throat and added, “We… didn’t handle things well. When you got the job. We were wrong to kick you out.”

I looked at my grandparents; my grandmother nodded like someone throwing me a rope across a river. “Thank you,” I said, because grace doesn’t mean forgetfulness. It means you count what’s owed and pay back what you can and forgive what you cannot and then you build a fence that tells you where you end and the world begins.

When my parents hugged me on the porch after the party and pressed the key into my palm, it didn’t feel like going backward. It felt like walking forward past a house you spent years propping up and deciding if and when you step inside, it will be because you choose to—on your terms, in your time.

That night, riding back to my grandparents’ in Megan’s car, I looked down at the key resting in my hand. Maybe I’d spend some of the summer there. Maybe I wouldn’t. The difference was mine to make. And that made all the difference.

Part Two

Life stabilized into something that felt like a rhythm instead of a trauma response. I worked two shifts a week at The Daily Grind because I wanted to, not because I had to, and I learned that caffeine lines are love languages when you’re seventeen and saving for textbooks. My grandparents added me to the list at the library so they could brag to strangers about my scholarship while pretending no such thing was happening. Megan taught me how to cook vegetables in a way that didn’t feel like punishment. Casey and I sat on the back steps of the school the week after graduation and tried to wrap our heads around the idea that our lives might be ours.

The guardianship paperwork went through quietly. Mrs. Thompson checked boxes I didn’t know existed; a judge signed his name like a man finishing a crossword. There was no courtroom drama, no baton pass. Just a line on paper that said Julia may legally live with her grandparents and an exhale I’d been holding so long I’d given it a room in my chest.

I still went to see my siblings every weekend. That was the condition and, truthfully, my own heart’s demand. The first few Saturdays were thick with awkwardness. My mother hovered and declined to ask for help. My father selected rooms to be in where I was not. But the kids—that love remained uncomplicated. Emma called me on Tuesdays to tell me about spelling words and new books and whose class pet threw up. Alex texted me secrets in all caps. The two littles drew pictures of me with my hair like spaghetti and shoved them into my backpack when my mother wasn’t looking, as if artwork was contraband.

I paid my grandparents back the two hundred dollars for the emergency card the minute I had it. My grandfather tucked the cash under the sugar jar and said I’d repaid them the moment I chose myself. He and my grandmother argued in whispers about whether I should start college with a used car; they compromised by paying for a bus pass and insisting on pepper spray in my backpack.

July brought orientation at State. Thompson Hall wasn’t fancy, but it smelled like new paint and possibility, which is close enough. The RA wore a lanyard heavy with keys and the kind of optimism you can’t untangle from twenty. I slept on a twin XL bed and listened to girls in the hallway worry out loud about people they hadn’t met yet. The cafeteria served burrito bowls and fear disguised as salad. I navigated the map and found the library like some girls find the shoe store.

When I came home for the weekend visits, I noticed changes so subtle I almost missed them. My mother asked about my classes like she meant it; my father clicked on an article about child psychology and left it open on his phone as if it had gotten there by accident. They’d hired a real babysitter on weeknights. She was nineteen and had a haircut that said she’d seen the inside of a campus library. She smiled at me like we were in a union and I clung to that for days.

The credit card line item disappeared from my mental ledger; my grandparents’ ledger of care didn’t. I learned to accept rides and casseroles and advice—things I’d been trained to believe were debts—without keeping a tally. Giving without goodbye had been my family culture; receiving without guilt became my rebellion.

Then the news cycle. Barbara’s nuclear forward of my 1,400-word text had primed the family for drama; the live mic moment had primed the city. But the court-ordered apology made the country sit up. You don’t get many chances to watch an adult learn how to say I’m sorry; you get fewer chances to watch them do it on television and mean it the second time they repeat the line. My mother’s mouth formed each syllable like a person learning a new language. My father stood next to her still as a commission.

I didn’t text either of them. I sent Aunt Barbara a bouquet with a card that said, “To our unofficial press secretary,” and she replied with a selfie of herself crying in a bathroom because she is dramatic and I love her for it.

Cousins called. Some apologized. Some asked for details because their parents had done a thing that felt eerily similar. I learned that truth begets truth, that when you crack open a story, the air rushes in and pushes oxygen into rooms you didn’t know you were locked out of. I listened and said, “Start small. One no. See who stays.”

The Sunday after orientation, my grandmother took me to a church she’d visited three times in twenty-five years. There were no velvet ropes and no handbells; the sermon sounded like a person opening a window. The pastor read a line from some Greek man that wasn’t in the Bible and said, Maturity is learning to manage the uncertainty of love. I didn’t cry. I also didn’t roll my eyes. That felt like something.

My parents kept inviting me to dinner. I kept saying yes sometimes and no sometimes. The first time I said no my mother texted, “We understand.” The second time, “We’ll save you a plate.” The third time, nothing—just a photo later of Alex with pasta on his face and the caption, He misses you. I think she was learning the same thing I was: you can teach people to love you only in the way you make it possible for them to. I’d made it possible on weekends. They learned to cook spaghetti on Tuesdays.

The scholarship money came with strings—GPA minimums and campus residency requirements—but there was a kind of giddy safety in knowing I could fail a quiz and not a life. I stopped waking at 3 a.m. to run numbers. I started catching myself in mirrors and not flinching. I bought a lamp for the dorm that lit my desk the way a person helps you see yourself: soft and uncompromising.

My mother asked me to coffee one afternoon at a place downtown that roasted their beans on-site and charged more than The Daily Grind for a smaller cup. She was on time. She ordered for herself and not for me. We sat and looked at each other like women who had almost lost something and were trying to determine if it could be shaped back into a new form.

“We were wrong,” she said without preamble. “When you got that job. We were wrong to kick you out. I was wrong to call what you did help when it was labor that cost you every part of being seventeen. I learned that from a therapist, so if it sounds like therapy, it is.”

I let the sentence unfold and then settle. “Thank you,” I said because honesty deserves acknowledgement even when it shows up late to the party.

“I can’t undo what we did,” she said. “I also can’t promise I won’t say something stupid and need to hear no.”

“I can promise to say it,” I said.

She smiled into her cup. “Good.”

On my eighteenth birthday, my siblings threw me a party in my grandparents’ backyard with paper crowns and badly frosted cupcakes and a handmade banner that said, YOU ARE OUR FAVRIT because Emma still spells like a human and not like autocorrect. My father grilled. My mother bought too many napkins. Aunt Barbara took photos like she was getting paid by the frame. Megan arrived with a tote bag full of things I didn’t know I’d need for dorm life, including a label maker, because she is a woman who copes with chaos by naming shelves.

We ate. We sang. We tried to play a board game and gave up because the littles kept stealing pieces and because we were laughing too hard to care about rules. When the sun went down, my grandfather lit two citronella candles and told me old jokes about people I’ve never met. My grandmother asked me to help her bring out the pie like she needed me for something easy and holy. We stood in the kitchen where the tile still held the day’s warmth and she bumped my shoulder with her own.

“People can change,” she said quietly, “and sometimes they don’t. But love is what you do after you know which is which.”

I nodded. On the counter my phone buzzed. It was a text from my mother: I set aside the hat with your things. In case you want it back.

I typed: Thank you. Might. Might not. Either way, I kept the note.

Then I put the phone face down and carried pie outside.

When August came and my grandparents helped me unpack into Thompson Hall, my mother and father came too. My father assembled a shelf. My mother made my bed with the kind of care you give to a baby and to a grown woman when you’ve learned both require thought. Emma stole my desk chair and spun; Alex tried to look unfazed and failed. I hugged them all and watched them go and stood in the doorway until the last possible second like a scared kid and then like a person who will be fine.

The first week of classes I woke too early every morning because my brain hadn’t learned yet that life doesn’t need me to be awake to keep spinning. I walked campus with a backpack that didn’t feel heavy. I learned where to find free coffee and quiet stairwells. I underlined things and had opinions. I called home when I wanted to. Sometimes my mother didn’t answer because she was busy and sometimes I didn’t because I was.

On a Tuesday in September, a girl from down the hall knocked on my door with puffy eyes and a story about her stepmother and a bag she’d already packed. I recognized all the pieces. I told her about guardianship and Mrs. Thompson and how a woman named Mara runs a shelter that grants breathing room. I wrote the numbers on an index card and slid it into her palm.

“Why do you hate your parents?” a boy in my Introduction to Psychology class asked later in the semester when the rumor mill got its teeth into the chalkboard. He meant why did you sue and why did the news care and why are you not easier.

“I don’t,” I said. “I hated what they did to me. I love them enough now to stop them from doing it again.”

He looked at me the way people do when you hand them a new tool and they’re not sure which end does the work.

When winter break arrived, I went “home” in sections. A few days at my grandparents’. A night at Megan’s because staying in her living room eating pancakes at midnight will always feel like a rescue. An afternoon at my parents’—pizza boxes and a movie where the kids fell asleep before the credits. I left the key to their house on the counter before I went back to campus, not as a rejection, but as punctuation. I’ll come when I want to, not because I have to.

Sometimes I catch myself from the side in the window of a bus or the glass of a campus building and I startle because the girl looking back wears her shoulders differently. There is grief in her, and there is grit, and there is a kind of peace that doesn’t need everyone else to behave to stay intact.

If you asked me now, Why do you hate your parents? I’d say, I don’t. That’s too small a story for what happened here. I hate systems that teach girls their value is in their usefulness and their place at the table is paid in hours of unpaid love. I hate how easy it is to turn daughters into infrastructure and then call them selfish when they ask to sit down. I hate that we’ve learned how to applaud apologies on television more than we’ve learned how to keep our promises in kitchens.

But my parents? They became people to me again when I stopped treating them like gods. People make mistakes. People make amends. People sometimes make neither and you love them from a distance because you love yourself up close.

In the end, what changed my life wasn’t the explosion in the group chat or the day in court or even the scholarship letter with its black pixels and its promise. It was the morning I told the truth to myself out loud in a cousin’s guest room and hit send on a message that said this is what happened without apologizing for how it sounded.

The day my parents shoved a suitcase across the kitchen floor and told me to leave was not the day my life ended. It was the day I started building a version of it that could hold me. By dawn, I wasn’t rich like people think. I was rich in a way they don’t teach—steady, held, unborrowed. And when I finally walked back through a door with a key in my hand, I knew it wasn’t because pity invited me; it was because I learned to invite myself.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was Rich. CH2

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was…

At Brunch, My Mom Smirked “You’re Lucky We Even Include You—Pity Goes A Long Way. CH2

At Brunch, My Mom Smirked “You’re Lucky We Even Include You—Pity Goes A Long Way” Part One They chose…

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left. CH2

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left Part One In…

At Dinner, My Sister Called Me A ‘POOR TRASH WORKER’ — Then A Guest Asked, ‘WHAT’S THE OWNER DOING?’ CH2

At Dinner, My Sister Called Me A “POOR TRASH WORKER” — Then A Guest Asked, “WHAT’S THE OWNER DOING?” …

I found out my husband had a mistress in a rather unexpected way my shampoo was running out way too fast! CH2

I found out my husband had a mistress in a rather unexpected way… my shampoo was running out way too…

My family texted “We need space from you. Please don’t reach out anymore. At all” CH2

My family texted “We need space from you. Please don’t reach out anymore. At all” my uncle packed them up….

End of content

No more pages to load