When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night

Part One

“You’re just a burden now, Rebecca.”

The words didn’t arrive like a shout. They came quiet and flat, landing in the dark like a nail on polished wood, small and decisive and impossible to ignore. I’d been home from the hospital for three weeks after spinal surgery. Tom stood at the foot of the bed we no longer shared, exasperation crossing his face like a weather pattern he couldn’t control. There was something worse in his eyes, too—pity.

Fifteen years of marriage learned me how to hide my pain. I nodded, smiled tightly, and said the kind of sentence that keeps a world from exploding: “I’m sorry you feel that way.” But inside, the floor of my life tilted. The woman who had been admitted to Lakeside Memorial six weeks earlier was gone; in her place lay someone physically broken and mentally waking up.

Six months ago, I was a successful interior designer, co-owner of Williams & Reed Studio, wife to Thomas Williams, a real estate developer with a knack for press releases and a golf swing that made other men clap. We lived in a colonial in Pinerest Estates that I’d rebuilt room by room—molding profiles, color stories, sconce placements like punctuation. Our life looked perfect on paper. I suppose that’s where it belonged.

Then came a rainy Tuesday, a red light someone decided didn’t apply to them, and an ambulance ride I remember in snapshots: ceiling tiles, a paramedic’s kind eyes, the taste of metal and fear. A shattered vertebra. Nerve damage. Surgery, then a measured, merciless set of words from my surgeon—recovery will be slow, painful, no guarantees.

Tom seemed supportive at first. Flowers. Daily visits that grew shorter. A new habit of checking his watch whenever a doctor came near. He moved me into the downstairs guest room “to make the stairs easier,” which was true and also made the rest of the house his again. There were sighs when I needed help bathing, impatience when pain meds turned my speech to fog, forced smiles when friends called to ask after me. It wasn’t just the accident that changed us. The accident peeled back everything we’d lacquered.

Three weeks after I came home, he took a call from his business partner, Rob, that lasted most of an evening. When he finally came in to say goodnight, I asked—habit more than curiosity—if everything was okay.

“It’s nothing for you to worry about,” he said, the words clipped at the end. “Just business.”

“I might be able to help,” I said. Before the accident, we’d talked through tough deals. My eye for how spaces sold often saved him money and made him look like a visionary.

He laughed then. Not the warm laugh I fell in love with at a charity auction, but a cold little sound that didn’t recognize me. “Rebecca, you can barely get to the bathroom without help. The best thing you can do is not add to my stress.”

“I’m still me,” I said quietly. “My brain works.”

He ran a hand through his hair. “I’m juggling the business, the house, the bills, your care. Rob says we should bring in a nurse, and honestly, I’m considering it.”

“Is it a burden to help your wife?” I asked, smaller than I knew I could be.

“You’re just a burden now,” he said, and left the room as if he’d hung a painting exactly where he wanted it.

Sleep didn’t bother trying. I stared at the ceiling and replayed our history, pausing on scenes I’d trimmed to fit the frame. Tom’s ambition had been quietly pushing us apart for years, and I was so busy managing a flawless house that I didn’t notice the cracks traveling across the load-bearing wall of us. My accident didn’t ruin our marriage. It arrived with the flashlight.

By three in the morning, clarity took a chair by my bed. I rolled to the little desk where Tom had placed my laptop “so you can still do something,” and opened the shared folder we hadn’t looked at together in years—joint accounts, investments, deeds, insurance, our estate plan drafted five years earlier when we still used the word “we” like a fact.

Ours was standard: everything to each other, then on to our siblings if the worst happened to both of us. But in the fine print, a clause about incapacitation hummed like a refrigerator in the night. I highlighted it. I made a list. I texted Daniel Cooper, our family attorney, at an indecent hour I knew he silenced his phone. I asked for a private meeting. When he offered to come to the house, I surprised myself: “No, your office. I need air that isn’t mine.”

I called my sister, Jen. She answered on the first ring like she had a sixth sense for when I needed her. “I need a ride tomorrow,” I said, skipping the parts that would make her furious for me. She said, “I’ll be there at one-thirty,” because sisters know when to ask questions and when to move the car.

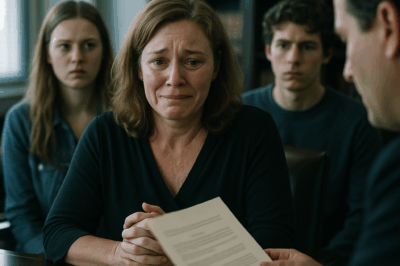

Daniel’s office smelled like coffee, paper, and the comfort of somebody else’s competence. I wore elastic waist pants and a back brace under a soft sweater; a far cry from the structured dresses I’d used to armor myself in rooms like this. He startled at the sight of me, recovered, and sat down across the desk like he was building a bridge between us.

“Tell me what you want to know,” he said.

“What happens to our assets if I remain partially disabled? What if I don’t?” I asked. “What about the businesses—Tom’s development company and my studio? In a divorce.”

He blinked once. “Are you…?”

“I’m not deciding today,” I said. “I’m making sure when I do, I’m not deciding blind.”

He walked me through Michigan’s equitable distribution, what “fair” meant when it didn’t mean “equal,” how courts treat asset division after long marriages—especially when one spouse’s earning potential changes because of injury. He explained how both businesses would be valued, how we could insulate my studio from his creditors, what my rights were to review our joint finances, how powers of attorney work if trust breaks.

By the end of the hour, I had a neat folder of answers, a pen that had marked more than money, and the number of a notary who doesn’t ask questions at eleven at night.

Jen and I stopped at a café afterward. I said the thing I hadn’t said aloud: “He called me a burden.” She squeezed my hand and said several words that would blister a saint. She reminded me of ways I’d built his success without title or salary: clients who became investors because I made a model home feel like a life, sales offices that closed deals because the lighting made people look like the best versions of themselves. Before she left me at home, I said, “I’m changing my estate plan tonight,” and for the first time since the accident, the world shifted somewhere other than under me.

I slept with a signed and notarized packet addressed to Daniel tucked under my pillow like a contract with myself. I’d amended my will to redirect my assets: to Jen, to a trust for spinal-injury patients who need grants for ramps and rehab and hope. Tom would receive the house he loved the way other men love a mirror. The mobile notary stamped her seal and left the envelope in my trembling hands. She didn’t ask why. She didn’t need to.

The next morning, Tom poured my coffee and asked about physical therapy with a brightness that felt like relief. “How was your meeting with Daniel?” he asked, buttering toast.

“Informative,” I said, and let the silence answer the rest.

Later, I made a second call I hadn’t planned. “Liv?” I said when my best friend picked up. “You know that garden studio you’re converting for your mom? How would you feel about me borrowing it for a while?”

“He called you a what?” Olivia said, and then: “Pack your bags.”

By the weekend, I was settled into a one-room space with bamboo floors, raised bed, wide doors, grab bars that looked like design features because she let me choose them. Tom carried my suitcases in, looked around, and said what he hoped sounded like a compliment: “Very accessible.” I thanked him for letting me go, which is to say: thank you for making this part easy.

In the quiet after he left, I opened my business email for the first time since the accident. Clients had been patient. Vanessa, my partner, wrote: When you’re ready—no pressure. I have ideas. The Madison project wants you even if it’s virtual. I wrote back and felt a flicker I recognized as mine: purpose.

“What now?” Olivia asked that night, two glasses in hand.

“Protect myself,” I said. “Rebuild my business on new terms. And gather information.”

She raised a brow. “Detective Rebecca.”

“Prudent Rebecca,” I corrected. “Vanessa’s husband, Marcus, is a financial analyst. He’s agreed to look over anything I send. Quietly.”

Tom texted a few days later: coming by at six. need to discuss something important. When he knocked, I positioned my chair near the sofa—no desk between us, no barrier, just air we both had to breathe. He looked surprised at what recovery looked like when you tried, then pulled a leather folio onto his lap and announced he was breaking ground on his biggest project, the Burlington. Then he slid contracts across my coffee table full of clauses that would route most of our liquid assets into accounts I couldn’t access, for years.

“I want my attorney to review these,” I said.

“Daniel represents both of us,” he said, just a little too quickly.

“I’ve retained separate counsel for personal matters,” I said, dropping the name of a woman he was afraid of: Marjorie Winters.

Something hardened and cracked in his face at the same time. He spoke about converting the den into a bedroom—gestures toward care, toward bringing me home. The timing tasted like strategy.

“Not yet,” I said. “This is working for both of us.”

Before he left, he looked at me and groped for the right thing. “About that night—I was tired, overwhelmed. I didn’t mean it.”

“Which part?” I asked. “Using the word or revealing the truth?”

He flinched. When the door closed, my hands shook. Then they stilled. I forwarded Marcus the documents. Within hours he wrote back in polite alarm: don’t sign. His analysis included numbers that told a story in which I was an ATM. I forwarded that to Daniel. I called Marjorie’s office for a consultation. The receptionist asked for my name and I hesitated for a heartbeat before saying it out loud like a promise: “Rebecca Williams.”

The next days turned into a rhythm. Physical therapy with Maria, who reminded me that breath releases muscles and truth releases everything else. Work calls with Vanessa, where we drafted a new model: I would lead vision and concept remotely; our team would execute on site. We could take clients anywhere now. We started saying “national” without laughing.

On a Monday, I returned to the house to collect personal things. I found the guest room erased. I found our bedroom eerily museumed. I found my mother’s pearl earrings missing from my jewelry box and a picture frame with nothing inside. I found Tom in the kitchen making coffee he didn’t offer me.

“Some items seem to be missing,” I said. “My mother’s earrings.”

“Are you sure?” he asked, in the tone of a man hoping history is subjective.

“Yes,” I said.

“I’ll look,” he said, and we both listened to what he didn’t.

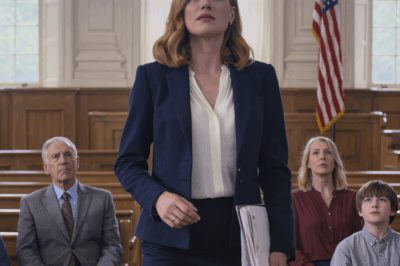

Daniel scheduled a meeting for Thursday. Tom showed up with a shark in a suit. I showed up with Daniel, with Marjorie, and with a forensic accountant named Eleanor whose polite questions peeled back careful lies. She asked why $175,000 in cash had been withdrawn over six weeks. She asked why those withdrawals didn’t appear in the company’s accounting. When Tom’s attorney tried to wave it away as “flexibility,” she smiled a little and said, “Flexibility usually leaves a receipt.”

Something in Tom broke before our eyes. He admitted the Burlington investors had pulled out. He called cash “consultation fees” and let the word sit there until we all understood it meant bribery. He confessed pawning my mother’s earrings and other small valuables for a “short-term loan,” promised he’d always meant to put them back. He said the restructuring had been an attempt to protect me and access my investments. He said he was drowning and saw me as a life raft.

“You don’t throw a person overboard and borrow their ring,” I said.

What followed were hours of guardrails: wrapping my studio in legal insulation, moving certain accounts into my name only, creating a plan to return my pawned things, a temporary separation agreement that acknowledged separate roofs and separate futures while we decided if there would be anything left to salvage between us. When Tom asked to speak to me alone, I agreed and listened to him talk about love that somehow always sounds like emergency sirens. I told him I would think about “us” after I was done thinking about me.

On my way out, Jen took my hand and squeezed it until we both could breathe. Dr. Foster came by for my home evaluation that week and said my body looked good for what it had been through, that stress could slow healing, that clarity speeds it. I said, “I’m getting there.”

That night Tom left a velvet box containing my mother’s earrings on the studio porch with a note: found them in the safe. must have moved them for safekeeping. I closed the box and set it beside Marcus’s analysis and breathed until the room belonged to me again.

Two days later, my phone lit up with a push alert: Prominent developer investigated for permit bribery. When Tom called, he didn’t ask for help. He told me I might get calls, that he would “handle it.” It was the first time in months he didn’t ask me to carry something that wasn’t mine.

The day Design Quarterly asked to feature our new model, I understood what the word reframe feels like in your hands. I told the editor they could have my professional story, not my marriage. They agreed; my wheelchair would appear in the photography as a design parameter, not a tragedy.

When the piece ran, my inbox filled with clients asking for beautiful solutions that were also kind—of course it took this to make architects remember people like me exist. My calendar populated with meetings for an accessibility initiative I agreed to join. The house I eventually bought was a mid-century ranch with long sightlines and hallways that welcomed wheels. I learned to see the chair as another tool in a designer’s kit: constraints create ideas.

The day before the divorce was finalized, I went back to Hion to sign two last documents. Tom and I stood in the foyer we’d posed in for holiday pictures. He handed me a list of the last items he’d redeemed from the pawn shop and I handed him a pen. “We were good at the décor,” I said. “We were terrible at the foundation.”

He winced and nodded. I left without turning around, because sometimes grace is not looking back while you’re becoming a different person.

Part Two

By the time the first feature’s praise cooled, Design Quarterly called again for a follow-up on accessible innovations. I sat in my new home office reviewing page proofs: kitchens where different counter heights looked like custom choices rather than accommodations; grab bars that read as sleek rail details; pocket doors that glided out of the way of wheels and walkers and children running with a dog. What had begun as survival became a niche my firm was suddenly known for: clever, beautiful, inclusive.

Vanessa called: “The Henderson contract came through. Full fee. They specifically asked for your oversight.”

“Third this month,” I said, trying to sound businesslike and failing into joy.

My phone pinged with a text from Tom. Sale of Pinerest closed. Proceeds transferred. Press conference at two. We rarely spoke now, and when we did, it was transactional, respectful, precise. He avoided charges through cooperation and settlements; he downsized the company; the Burlington site sold to a competitor who brought in a different architect and better ethics. He sent occasional messages about redeemed items and property considerations. I replied with thanks. We remained the only two people alive who could say we knew what our lives had once been.

I found a different kind of life. I joined the board of the Lakeside Heights Accessibility Initiative. The first time I rolled into a meeting and saw city planners and business leaders turn to listen, not because I was a symbol but because I understood both the art and arithmetic of making spaces that hold more people, I felt a click in my spine that had nothing to do with nerves. A veteran advocate named Sandra approached afterward and said, “A lot of us start this work for ourselves. The ones who stay do it for everyone.”

At home, Maria came weekly to keep my body honest. Some days my legs remembered what they could do; other days my chair carried me through. I learned which aches meant progress and which meant “sit down now.” Nights were quiet in a way that carried me rather than crushed me. My kitchen smelled like garlic again. I started sleeping without waking from dreams that left me on my knees in an empty house.

A year after surgery, Dr. Foster emailed to remind me that anniversaries matter in medicine and in hearts. I made an appointment and brought her the whole story—the accident, the marriage, the exit, the new house with a window wall that made winter bearable. “Your scans look strong,” she said, smiling. “So does the rest of you.”

The day I said yes to mentoring newly injured patients, the hospital paired me with a 29-year-old teacher named Aria who’d been hit on her bike, furious in a way that felt like a pulse. Our first meeting took place under fluorescent lights and felt like being a translator. I told her the small truths alongside the slogans: your people will surprise you, both ways; your bathroom can be beautiful and safe; rage is oxygen the first months and you’ll breathe it until you don’t; nothing about this makes you less—less desirable, less necessary, less you. She gave me a look like we were safe enough to be honest and said, “I don’t believe you. But I want to.” I told her that was a beginning.

My studio became a hub for clients who had never seen themselves in catalogs. A chef who couldn’t stand for long but insisted on hosting Sunday dinners. A grandmother whose Parkinson’s made narrow doorways feel like insults. A boy with a prosthetic who needed a ramp that looked like a skate park when his friends came over. We made houses that made space for lives to happen. I learned there’s a difference between designing rooms and designing dignity, and my hands got better at both.

One afternoon, Vanessa forwarded a blunt email from an editor: We’d like to feature Rebecca’s approach to “beauty as a form of care.” The phrase lodged under my sternum and stayed. I thought of the night I changed my estate plan with a shaking hand and a stranger’s stamp, how what I did that night wasn’t vengeance. It was care—care for the woman who would have to live with my choices in a year, in five, in the quiet hour before dawn.

Sometimes kindness and boundaries are the same gesture, just seen from different rooms.

The divorce papers went through with the dull thud of a book shutting. The settlement protected me, acknowledged the entanglements of two businesses and one long gallery wall of photographs. I sold the colonial without going inside again. A young couple with a baby bought it; I hope the echo in the foyer is friendlier for them.

I bought a ranch brimming with light and planted a wisteria that will take years to look the way I see it in my mind. The accessible choices—wide hallways, lever handles, sloped walkways—disappeared into the design the way a good seam disappears into a dress. Friends came over and only noticed how comfortable it felt.

On a Tuesday that started like any other, I received an email from Design Quarterly that made me laugh until I had to sit down properly so I didn’t end up a cautionary tale in my own article. They were naming me one of their Innovators to Watch. Me, the woman a man once dismissed as a burden.

I went to lunch with Jen to celebrate. She toasted with iced tea because it was noon and because she likes to do the right thing even when I don’t. “To the new Rebecca,” she said, and I corrected her, smiling, “To the real one.”

After lunch, we drove past the lake that had witnessed all our childhood summers. I asked her to pull over at the public pier. I rolled out and let the lake’s noise soak my bones. A father taught a child to tie off a boat line. A college couple took a series of photographs that could not all possibly be good. Elderly women in sensible shoes power-walked past us and gossiped about a baking competition as if it were national security.

Tom called while I watched two ducks choose each other again. “I won’t keep you,” he said, unusual for him. “I saw the Design Quarterly piece. It’s… good. So are you, apparently.”

“Apparently,” I said, and we shared a thin, fond laugh stretched across a past tense. He told me his company had stabilized in a smaller form, that he’d sold the last parcel of the Burlington dream. He did not ask me to come see the new office. I told him about the mentorship program and about a grant the foundation had given a single mom for a ramp. He said, “That sounds like you.” We said goodbye and didn’t say take care because we both meant it.

That night I wrote in my journal—something my therapist suggested when too much stayed in my head and turned menacing. I wrote about the first time Tom and I danced and about the last time I let him decide what I needed. I wrote the sentence I had been avoiding in case it broke my heart by being ordinary: My marriage ended for private reasons that deserve to remain private. And then I wrote the sentence that felt like a window open in January: That night, when he called me a burden, I made a different vow—to myself.

A year to the day after my surgery, I rolled into my kitchen and made pancakes. The batter tried to be lumpy and I insisted on smooth. I plated the first one for myself and the second for no one in particular and put it on the counter anyway the way my mother always did, because second pancakes are for hope. The wisteria on the trellis outside was still not what I wanted it to be. Growth takes the time it takes.

An email from the hospital’s patient advocacy program arrived mid-pancake: Would you speak at our fundraiser? We want to tell the story of recovery that looks like a life, not a miracle. I said yes before I had time to be clever.

That evening, I wheeled to the back door, pressed the lever, and rolled out into my garden—the first garden I’d ever planted for myself and not for a magazine spread or a man with opinions about boxwood. Lavender brushed my hand and the scent rose like a memory from before everything. A neighbor waved. Somewhere down the block a child played a trumpet like he meant it and maybe one day he would.

I thought of the version of me who lay in a guest room counting ceiling squares and believing for nine minutes at a time that her life might already be over. I wanted to tell her: you are allowed to make the decisions that keep you alive. You are allowed to change paperwork and locks and the story you tell about who you are. You are allowed to be more than one thing in a single lifetime. You are allowed.

Tom’s words changed everything that night, but not in the way either of us imagined. He thought he’d named my end. He unwittingly named my beginning. When someone who promised to carry your weight decides you are the weight, you stop waiting for rescue and start building a different kind of house—one where the doors open for you, one where beauty is a form of care, one where you are never, ever the burden again.

Part Three

The fundraiser ballroom at Lakeside Memorial smelled like coffee that had tried hard and flowers that didn’t have to. A hundred and fifty people in rented kindness lifted their faces toward the stage where a glossy loop played patient stories edited into triumph. I watched from the wings with my notes folded in half, then quarters, then eighths, until the paper felt like a small, determined talisman in my palm.

“Rebecca, you’re up in two,” said the event coordinator with a voice like a gloved hand.

I rolled into the light and the murmur settled. There are speeches that ask for money and speeches that ask for belief; mine tried to do both. I told them the clean version of a messy year. I talked about beautiful kitchens with counters at two heights so a grandmother could roll and a grandson could stand; about staircases that invited those who climbed and handrails that meant dignity for those who could not. I said the sentence that had carried me from a guest room to this stage: “Beauty is a form of care.” The room didn’t clap at the line. It breathed.

I saw Vanessa near the back, eyes shining like she’d installed them herself. I saw Sandra, hands folded, mouth set in that line advocates wear when they refuse to be thanked for the work. I did not see Tom, and then I did, at the edge of the room, not hiding and not brass enough to be obvious, looking like a man trying to learn a new language in a crowd that spoke it since birth.

After the applause, a woman about my age cornered me near the bar. “My husband says grab bars make a bathroom look like a hospital.”

“Tell him hospitals wish they looked that good,” I said, and she barked a laugh that turned into a promise to call the studio Monday.

Near the coat check, Tom approached with his hands in his pockets like a teenager. “You were… real,” he said.

“That’s the only kind left,” I answered.

“I brought a check,” he added, then grimaced. “That sounded transactional. It isn’t.”

“Even if it were, the ramp still gets built,” I said.

He nodded and looked over my shoulder at the stage. “I’m learning there are ways to build that aren’t about square footage and press releases.”

“You always did like a new project.”

He winced. “I’m working on being someone I didn’t give enough time to before.”

“I hope you like him,” I said, and meant it.

An hour later, in a conference room that smelled like new carpet and second chances, Aria tried on a dress a volunteer had brought—a simple black thing with clever panels. She stood for ten minutes with her exoskeleton whirring like a mechanical prayer and whispered into my shoulder, “I thought standing was an emotion. Turns out it’s a place.”

The gala raised enough to finance ramps, therapy sessions, and a job training pilot. When the final number flashed, the room sounded like a roof lifting. I texted Jen: It’s not a miracle. It’s logistics. She replied: Logistics are miracles built by sisters.

The next week, a developer I swore I’d never share oxygen with again called Vanessa: the Burlington site—Tom’s old white whale—had been purchased by a firm that wanted to rebuild the project from the studs of its reputation out. They wanted an accessible anchor: a community center, public-facing, practical. They wanted me.

“Conflict of interest?” Vanessa asked.

“Conflict of history,” I said. “Different animal.”

We negotiated a contract that read like a boundary. I insisted on public bathrooms that worked for people in chairs and people with strollers and people with bad knees and pride. I insisted on benches that didn’t pinch dignity. I insisted on sightlines that welcomed those who found crowds a bruise. The new firm said yes and meant it.

For the build, we hired Ethan Hall, a general contractor with hands like a blueprint and a habit of listening all the way to the end of a sentence. He’d built houses and barns and a reputation for doing the invisible things right. He showed up to our first meeting with a notebook full of questions and no speech about being the good guy. When I wheeled him through the plans, he asked, “If I put the handrail a half-inch lower, does it keep a kid from feeling like it’s for old people?” It was the right question. He had a face that looked like winter you could trust and a laugh that startled him.

We fought for permits and won them. We fought for budget lines and won some of those too. There was a moment when a city inspector rolled his eyes so hard I thought he might sprain something. Ethan leaned in and said, very mildly, “We build this right in paperwork or we build it again in court.” The stamp hit the page like a confession.

At home, the wisteria offered a few shy blossoms that tried to pretend they’d been there all along. Maria cheered them like a coach.

That spring, I updated my estate plan again. Daniel and I sat in his office with mugs pretending to be coffee and adjusted the trust to include a fellowship for designers with disabilities. “You’re building a guild,” he said.

“Maybe I’m planting a row of people who won’t have to explain why a lever handle is dignity.”

He smiled and slid the documents over. I signed with a hand that now understood its own strength. I included a letter to Jen, simple and spare: If you’re reading this, I hope the wisteria finally did what I saw in my head.

When I left the building, the sky was one of those lake skies that can’t decide, and I thought: me too, and it’s okay.

Part Four

Construction has a sound I learned to love years before I loved a man. The Burlington site clanged and hummed and occasionally swore. Ethan walked the floor with a pencil behind his ear and an attentiveness that made subcontractors behave. He found a way to hide a lift in plain sight so it looked like part of the staircase sculpture, and when I told him I wanted a grab bar that doubled as a shelf for a mother’s purse, he made it out of matte brass that winked and worked.

“We’re designing for how people actually move,” I said to the city council during a site tour.

“Isn’t that expensive?” one of them asked.

“So is redoing a lawsuit,” Ethan said under his breath.

Aria came on site on Fridays as part of the job training pilot. She took measurements, learned the slow romance of a level, and developed an opinion about tile that could start fights. One afternoon, she tapped a drawing with a pencil and said, “This light switch placement isn’t about ADA. It’s about not making a teenager ask for help in front of his friends.” I recommended her for a paid internship before she could blush through the sentence.

The press did what press does when it senses a second chance for a place that embarrassed itself: it arrived with cameras and the hunger to forgive if forgiveness came with a ribbon cutting. They called me an expert and the project a model; they called Ethan the guy who made it real; they called Aria a symbol and then—after I sent a pointed email—called her a designer. Progress.

One morning, Tom showed up at the edge of the site with a paper cup and an expression he used to wear when a deal depended on good weather. He’d kept his distance the past months, a courtesy I registered as respect. Now he stood quietly until I waved him in.

“Old ghosts,” he said, looking around.

“New house,” I answered.

He nodded toward Ethan, who was squinting at a column like it owed him money. “That the contractor?”

“That’s the builder,” I said, and Tom took the cue.

He told me he’d settled a suit with a former partner, that it had cost him more money than he liked and less than he deserved. He said he was leaving town for a while, a development in Colorado that might need a winter coat and a different version of himself. He did not ask if I would miss him. “I’ll send paperwork when the last pawned item is back,” he said.

“Make sure the paperwork is the last thing,” I said. He understood the grammar: give the ring back before the receipt.

When he left, he shook Ethan’s hand. There was a moment where men measure each other and decide not to swing. It passed.

That afternoon, a storm rolled off the lake like a grudge. In twenty minutes, the sky went from moody to medieval. Power snapped off from the north side to the river. The site closed early, and I drove home behind a procession of brake lights.

At dusk, half the neighborhood gathered under my covered back porch like it was a stage and we’d been cast together. The accessible house that had been my private solution became a public plan B. We plugged phones into my backup battery, lit candles at safe heights, and made a ridiculous dinner of pantry pasta and porch laughter. Mrs. Alvarez from two houses down cried when she realized she could roll her husband’s oxygen tank through my wide doors without performing geometry.

“Your house is showing off,” she said.

“It should,” I replied. “It worked hard for this.”

Around nine, a tree on the corner split like a decision and the street went black. Ethan, who had driven over with a chainsaw and the expression of a man who plans on being useful, set to work with two neighbors while the rest of us practiced the underrated art of staying out of the way. When the road was clear enough for emergency vehicles, he came back to the porch soaked and grinning, a collie’s worth of leaves plastered to his jacket.

“You keep a chainsaw in your truck?” I asked.

“Sometimes lumber grows on trees,” he said, then looked at me, surprised at his own joke.

We sat near the edge of the porch and watched the generous dark. Every neighborhood has a night when it becomes itself. That was ours. Teenagers hauled coolers like EMTs. Someone’s dad played harmonica with the seriousness of an oath. The trumpet kid two doors down learned restraint. When the power crept back in sections, it felt like a favor.

Ethan walked me inside at the end of it and stopped just past the threshold like a man who knows too much furniture to think a home is just studs. He ran a hand along the wall at shoulder height. “You can tell this place was built by someone who lives in it,” he said.

“Most places should be,” I answered.

He didn’t touch me—not my shoulder, not my hand—but something in the room did. When he left, I found a card on the console table where my mother’s earrings lived now. It just said: If you ever need a shelf to hold the world while you breathe, call. I didn’t, not that night. But I wanted to.

The next day, Aria texted a photo: her classroom had installed new desks that allowed a kid with a wheelchair to roll in without announcing himself. The caption read, simply, We remembered him on purpose. I stared at the image like a painting that teaches the eye what to look for.

Part Five

The Burlington reopened as the Harbor Center on a Saturday in June when the town remembered how to be a postcard. There were hot dogs and speeches and a ribbon that made everyone cry because it wasn’t red and ceremonial; it was woven from messages we invited people to write in the weeks before—gratitudes, names, small wishes. Ethan cut it with a pair of comically large scissors after I refused and the mayor pretended she insisted.

We’d built a lobby that felt like it was listening. The bench heights varied as if designed by a choir. The bathrooms were so pretty people took selfies in them, which was both the point and the bribe. A toddler ran his chubby hand along the continuous rail and yelled “weee!” as if gravity were a rumor. In the community kitchen, an elderly man with a cane made tea on an induction burner that didn’t care if you got distracted. The place worked the way my good projects always have: people forgot the design because they were too busy living in it.

Ethan found me near the glass wall where the lake pretended to be an ocean. “I have a confession,” he said.

“Those are rarely followed by citations,” I replied.

He looked down, then up, choosing the hard thing. “I lost my wife three years ago. Cancer. For a long time, I built things because I couldn’t build her. Then this project happened and it felt like… not fixing. Just making again. You did that.”

“I drew the lines,” I said. “You made them stand.”

He nodded, eyes shining the way men’s eyes do when they refuse to apologize for feeling. “I don’t know what to do with wanting something like a life again.”

“Start small,” I said. “Install a shelf.”

He laughed. “Dinner?” he asked, then rushed—“Friends or more. Whatever you say is the right answer.”

“Yes,” I said, a word that fit all kinds of futures.

When the speeches ended and the crowd thinned into the first ordinary day of the building’s life, I rolled into the quiet and touched the cool rail we had argued about for weeks. The world goes on. It was a mercy.

Two weeks later, Tom’s manila envelope arrived by certified mail. Inside: a pawn ticket marked redeemed, a receipt with a balance of zero, a final list with boxes checked in a pen I recognized from a decade of shopping lists. There was a note, handwritten in an unsteady block: I don’t know if there’s such a thing as making it right. But I know the difference between less wrong and more wrong now. Thank you for teaching a class I didn’t sign up for.

I placed the note in the drawer with Daniel’s letters and Marjorie’s invoices and felt a small knot loosen in a place surgeons can’t reach. I texted Jen a photo and she wrote back: I hope he finds flat water. I hoped that too.

Work surged in the way a life does when you finally align it with your bodies—your physical one and the one made of choices. We hired Aria full-time. She cried and then hit a deadline with clean drawings and two jokes written in the margins for the contractors. I started a lecture series at the community college: starter courses in inclusive design taught by people who had to navigate one world while dreaming another. We put “beauty as care” on the syllabus with no italics and no fuss.

I went on a first date for the first time in twenty years. Ethan insisted on a place with wide aisles and seating that didn’t turn chairs into obstacles. The hostess—smart, bless her—led us to a table without commentary. We ate grilled peaches and talked about the mechanics of attention. He worked around my story’s sharp edges without bubble-wrapping them. I asked about his wife and he told the truth without making me hold it. He walked me to my door and paused, that old choreography we teach our nervous systems in adolescence.

“Kiss goodnight?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, and he kissed me like a person who had learned to meet people where they are.

I did not combust. The world did not fix. It turned, and so did I.

Summer burned into September like a wick. The trumpet kid up the street got better. Mrs. Alvarez’s wisteria outpaced mine and we both pretended it didn’t matter. Vanessa and I signed a contract for a project in Chicago that meant flights and a hotel and the logistical ballet of travel with a chair. I did it, not because I’m brave, but because sometimes you decide your life will include the world.

At the end of the month, Design Quarterly sent a photographer who knew how to shoot glass without making it sulk. He captured the Harbor Center at dusk when the lobby glowed like a low promise. My wheelchair made it into the frame because it always had a right to be there. The caption didn’t mention it. We had finally learned how to let a tool be a tool and a person be a person.

On a Tuesday, Aria rolled into my office with a grin she couldn’t contain. “They made my temporary position permanent at school,” she said. “I’m teaching an architecture elective in the spring. Accessibility in Practice.”

I hugged her and then scolded my back and then hugged her again. “You’ll be terrible at it at first. Then you’ll be dangerous.”

“I learned from the best,” she said, and my throat did an undignified thing.

That night, I wrote a letter to my future self and dated it five years ahead. I wrote: you are allowed to love twice. You are allowed to be proud of a house and a body and a boundary. You are allowed to know the difference between pity and compassion and to choose only one of them when you look in the mirror. I sealed it and put it in the drawer with the other papers that had saved me.

Part Six

Winters in our town always arrive like they’re late and trying to make up for it. The lake goes stern, the trees stop pretending. Ethan installed a narrow shelf on the wall near my back door—just big enough for keys and letters and the small notion that life can be set down without being dropped. Every time I came in from the cold, I put my gloves there and felt like I’d participated in a ritual older than grief.

We spent holidays with people who had learned to wrap presents without adding a battle I hadn’t agreed to fight. Jen brought her kids, who had opinions about gingerbread architecture. Vanessa came with a pie that looked like it hired a stylist. Maria laughed in my kitchen and told me to stop lifting things I didn’t need to lift. We toasted with sparkling cider and then, later, with the expensive champagne Olivia insisted was an investment in good stories.

In January, the hospital sent me the annual summary of the foundation’s grants. I read every line like a ledger balanced in holy arithmetic: ramps, therapy hours, job training slots, accessible sinks in a daycare that decided to tell toddlers the truth early—this world is for you too. The fellowship application list made me clap in my own kitchen: a veteran with a carpenter’s eye and a sketchbook of public benches; a painter who needed a studio she could reach; a coder who wrote software that mapped routes by ramp and rail instead of stairs and stress.

One afternoon—the kind of winter light that makes you believe in forgiveness—Tom called from Colorado. It had been months. “I wanted to tell you I got married,” he said. There was a smile in his voice that I recognized as genuine. “Her name’s Claire. She’s a landscape architect who insists on native plants and honesty. I think you’d like her.”

“I probably would,” I said, and we both heard the soft door close on a room we no longer needed to enter.

“Thank you,” he added. “For… whatever it is that happens when someone lets you fall apart without letting you ruin them.”

“You figured that one out,” I said. “Good luck.”

After we hung up, I sat very still. There are endings that feel like cliffs and endings that feel like docks. This one had boards and a view.

In March, Ethan and I took the train to Chicago for the project. He slept with his mouth slightly open and I watched the country slide by in its patchwork of winter and almost-spring. At the hotel, they’d given us the room I’d requested: a shower with a bench that didn’t look like a punishment, a bed that wasn’t so high you needed an apology to get into it, a desk that invited elbows. We ordered room service and ate french fries like teenagers.

“You know,” he said between bites, “I keep waiting for the movie moment where we declare something. But I like this. The declaring is in the doing.”

“Declarations are for nations,” I said. “Homes are for people.”

He grinned. “That sounds like something you put on a tote bag.”

“I already did,” I admitted.

The project went well. We built a lobby that could hold a stroller brigade, a rush of commuters, a man with a cane who didn’t want to be noticed, and a woman in a chair who did. We ate at a restaurant that understood aisles, and I didn’t cry, which felt like progress or relief or both.

Spring back home arrived like forgiveness does—slowly, then everywhere. The wisteria finally decided to keep its end of the bargain. It exploded into purple like a controlled accident. I rolled under it and laughed because of course it took two years to look overnight.

On the anniversary of the night I changed my estate plan, I cooked dinner for the people who had stood around me until I could stand my own life. The table was a lesson in design: chairs that slid, a bench for choice, plates that didn’t judge clumsy hands. Olivia made a toast that could have been a comedy routine and a prayer.

“To Rebecca,” she said. “Who turned the ugliest sentence I’ve ever heard into a foundation, a fellowship, a building, and a garden. You were never a burden. You were ballast. And now you’re also wind.”

I cried in a way that didn’t scare my body. I looked around at faces that had carried me and let me carry them. The house held the sound and handed it back warm.

Later, when everyone had gone and the dishwasher hummed its practical lullaby, I wheeled to my desk and pulled out the letter I’d written to myself five years ahead. I didn’t open it; it wasn’t time. Instead, I wrote another, shorter one, addressed to the woman I had been the night a man mistook my weight for something he had to drag.

Dear me,

You did it right. Not perfectly. Right.

You changed papers and doors and your mind. You learned to call a tool a tool and a person a person, including yourself. You built things that make it easier for strangers to be alive. You loved again without pretending the first love didn’t happen. You gave your mother’s earrings a soft place to land. You turned a word meant to shrink you into a room big enough for a town.

When someone called you a burden, you became a builder. That night was the hinge. This house is the door. Walk—or roll—through it as many times as you like.

Love,

Rebecca

I signed it and tucked it beside the others. Then I turned out the lights, rolled to the back door, and listened to the trumpet kid practicing a scale he was finally getting right. The wisteria moved in the dark like a curtain between acts. Somewhere on the lake, a boat bumped its mooring and settled. Inside my chest, something answered: I’m moored. I’m free.

The next morning I woke before the sun and wheeled into the kitchen. The batter tried to be lumpy. I insisted on smooth. I poured a second pancake and set it on the counter for no one in particular and everyone I loved. Growth takes the time it takes. Doors open when they are ready. Foundations hold when you pour them level and honest and let them cure.

This is the life I built on purpose. And it is, finally, light enough to carry.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will Part One I never thought I’d…

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement Part One I never…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then… …

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead Part I — The Test Shot…

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything Part 1: The…

They Begged Me to Pay for Surgery—Then I Found the Sports Car Receipt.

They Begged Me to Pay for Surgery—Then I Found the Sports Car Receipt Part One The call came at…

End of content

No more pages to load