When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side?

Part I — The Unicorn in the Counselor’s Office

My daughter hit my waist like a fastball, a seven-year-old comet with both arms welded around me. Her heart was beating through her sweatshirt; I could feel it with my palm the way you can feel thunder in a fence post. I set her on the counter, kissed her forehead, and reached for the only medicine I trusted in that moment—French toast. Cinnamon, egg, a splash of milk, the slow golden sizzle. She watched the pan as if the surface might crack and swallow us whole.

“Bad day?” I asked lightly.

Her mouth tugged sideways. “Mommy… something happened, and I think I’m supposed to tell.”

Everything in the kitchen seemed suddenly too loud: the vent humming, the dog’s nails on tile, a distant lawn mower droning like a threat. I slid the plate in front of her, cut the toast into squares, and waited.

She told me about the counselor’s office, about a “special game” with a stuffed unicorn, about hands guiding her in ways no child should be guided. She didn’t have the words—thank God—but she had enough. She said his eyes looked weird. She said he told her secrets were good if they keep adults happy. She said he promised something bad would happen to me if she told.

I didn’t make it to the sink. I folded at the waist, braced on the edge of the counter, and retched until there was nothing left to give back to the world. When I looked up, my daughter’s knees were drawn to her chest on the barstool, ankles crossed, small fingers worrying the seam of her jeans.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, and those words were nowhere near big enough.

I was a doctor—pediatrics before I switched to community medicine, which meant forms and vaccinations and new moms with questions I could answer without thinking. I believed in systems. I believed in the quiet efficiency of good policy. I believed in school counselors. I believed in doors with windows and mandatory reporting and all the ways we have invented to keep children safe.

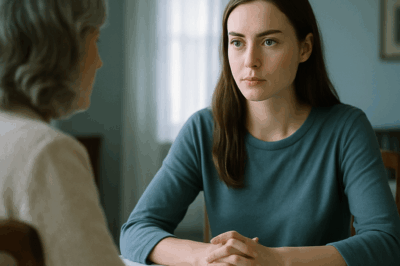

I called the school. The principal invited me to sit in a room that smelled like laminate and lemon-scented wipes. Her smile never reached the bones. “Kids pick up stories,” she said, lacing her fingers. “Sometimes they test boundaries. Sometimes they want attention.”

“She doesn’t make stories,” I said. “She hates the spotlight. She sleeps with a book about frogs. She still thinks mosquitoes are fairies with bad tempers. She is not inventing this.”

“We’ll look into it,” she said, a sentence that means nothing when spoken by people protecting a building’s reputation.

I didn’t call the police next because my brain was still a storm of disbelief and I wanted authority to fix what authority had allowed. That was the mistake I can name now in small, neat letters. The school called the police before I did. By the time I arrived at the station, the desk officer knew my name, my daughter’s teacher, and the phrase the counselor had used for the “game.” He squinted at me the way men squint at women they suspect of being dramatic. “Ma’am,” he said, “we’ll take a report. But be careful not to put ideas in a child’s head.”

I drove home furious enough to raise the temperature of the car. My daughter was building a Lego dragon on the living room rug. I sat with her and made a tail out of yellow bricks and felt like an actor in a play where the audience knows the ending and the cast doesn’t.

It took me until midnight to remember the safe. It lived behind sweaters I never wore in a city that doesn’t do winter with sincerity. Inside: my grandmother’s earrings, a brooch from a yard sale I’ll never forgive myself for buying, and an envelope with a phone number scrawled on cheap paper.

Years ago, when I was very new and very earnest, a man came into the ER with a bullet in his shoulder and tattoos that made other nurses step back. Nobody wanted him. I took him. I numbed, irrigated, stitched, and joked clumsily about staying away from bullets in the future. He laughed once, the kind of laugh that comes up from a place you don’t want to visit, and slid the paper into my palm.

“If you ever need someone taken care of,” he said. “No payment.”

I filed the number under I Will Never Use This alongside the mental list of baby names I’d never get to give and the gratitude I never sent to the woman who held my hand through my husband’s funeral. Now I held the paper like it might burn me and dialed.

“I remember you,” he said. His voice was gravel and midnight.

There was a mirror in the hallway that showed a woman in a T-shirt with bleach spots and a face that had stopped believing in the next five minutes. “It’s about my daughter,” I said. Then I told him. All of it. The unicorn. The counselor’s office. The principal’s pretty smirk. The officer’s patient condescension. My daughter’s small hands making fists around the air.

“Name,” he said. “Address. Car. Routine. Give me everything you know.”

“Are you sure?” I asked, but what I meant was Am I?

“You didn’t call for advice,” he said. “You already stepped over the line.”

I typed out what I had: the counselor’s full name, his morning run route, his habit of buying coffee at the strip mall, the model of his car, the color of his jacket, the picture of him from the school website, chin up like a challenge.

He replied with one word: Understood.

I sat on my daughter’s floor that night and watched her sleep. Her unicorn lay on its side, its plastic eye catching the streetlight and reflecting it back like a question I couldn’t answer. I cried without sound, because sound wakes children and I had taken enough from her day.

Part II — The Call and the Silence

The phone rang at 4:37 the next afternoon.

“It’s done,” he said.

“What does that mean?” I whispered, like the words might crack and cut my mouth.

“It means he won’t look at another child again,” the man said. “Not with eyes, not with anything that lets you see. Move forward.”

He hung up. The room was very quiet. I could hear the dog’s breath. I could hear the little metal tag on my daughter’s backpack knock once against the chair leg in the kitchen. I could hear the refrigerator motor cycling like it had always done, like it always would.

There were no sirens. There were no headlines. There was a call from the principal two days later: “We’re so sorry for the misunderstanding. The counselor has taken a leave to address… personal matters. We’re reevaluating protocols.”

“Now it’s too late,” I said, and in the dead space before I hung up I could hear the shape of what else she wanted to say but didn’t—about donors, about rumor mills, about stubborn women who don’t know how to let things go.

The police came, polite as a casserole. They asked if I had heard anything. They asked if I knew anything. They asked if I had recently been in contact with the counselor. I said no. I said we had filed a report. I said my daughter was in therapy, which was a lie; I was still calling lists and being told about availability as if healing had a calendar.

At night I dreamed of sirens and woke to the house being perfectly itself. My daughter began to have nightmares that sounded like the first five seconds of a scream that had forgotten its way out. She would sit up and clutch her unicorn and whisper that the man was in the closet and promise she hadn’t told the secret and then remember that she had and sob like a faucet with a hand over it.

“He can’t hurt you,” I told her. “Not ever again.”

“How do you know?” she asked.

Because I did something you’ll hate me for someday if you grow up into a person who loves rules more than children, I thought. Because I found someone who takes monsters off the board without needing to read them their rights. Because the light kept flickering and I learned how to strike a match.

I told no one—not my mother, not my oldest friend from residency, not the other parents at the park who adopted a collective tone when they asked how school was going. I went to work and weighed babies and checked ears and put my hand on shoulders and said “this is normal” and “this is fine” and “this is what we do,” and inside I was an engine running red.

A black sedan started appearing at pickup. It sat across the street like a question mark. Two men inside, faces invisible behind the tint. We changed routes home. We changed routines. We changed which lamp I left on in the living room.

The summons came. The detective was a woman with a half-moon scar near her eyebrow and the posture of someone who had spent most of her adult life asking cops to repeat themselves. “Any recent contact with the counselor?” she asked. “Any disputes? Did anyone else express anger toward him? Did he have enemies?”

“If he did what we think he did, everyone should be his enemy,” I said before the part of my brain that moderates tone could catch up.

“Do you know anything that could help us?” she asked, eyes steady.

“No,” I said, because the truth is sometimes a house and sometimes a door.

Afterward I drove to the school anyway and sat in the parking lot and watched the principal usher children into minivans with a smile that had been trained like a dog. I thought of the ER years ago, of the man with tattoos who had thanked me for stitching him with the care I would give anyone. I thought of my husband, five years gone now, and the fierce gentleness he used to deploy when someone else’s opinion of his wife threatened to alter her shape. “You are allowed to be exactly as angry as you are,” he would say. I put my head on the steering wheel and cried like I was trying to clear a windshield with tears.

Part III — Digging

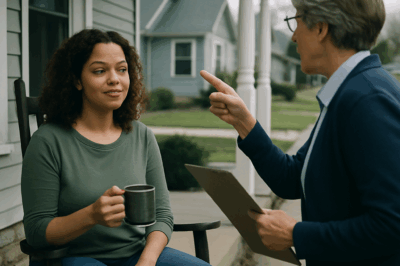

I started digging in the hours that followed bedtime, when the house was quiet and the dog asleep and the choices you make echo. I searched public records: the principal’s name tied to a board, tied to a campaign, tied to an award given by people who had never visited the school during bus duty. I found a complaint from a decade ago about an employee at a different school. The principal’s name appeared in the footnotes like a shadow.

I made an anonymous post in a parents’ group so carefully constructed that I used none of my own words. I asked if anyone had ever felt unsettled by the counselor, if anyone had ever heard about “games,” if anyone had been told their child “made things up.”

The first responses were predictable: Don’t start rumors. Don’t ruin lives. Protect the innocent—but they meant adults in cardigans, not children in sneakers. Then the private messages began like rain after static. A mom whose daughter didn’t want to see the counselor anymore but they told her it was “just anxiety.” A dad whose son had been asked “weird” questions about hygiene with the door closed. A teacher who remembered a girl crying in the hall after being sent to “talk.” None of it would have satisfied a prosecutor. All of it made me sure.

I hired a lawyer who wore rumpled suits like an argument you can’t swat away and had daughter-shaped photos on his desk. He told me to document everything. He told me to write down times, dates, words. He told me to stop talking to people on Facebook. He told me we could do this the clean way.

I also emailed a journalist. He called me that night from a number that didn’t exist. “I’ve heard whispers,” he said. “Now I’m hearing sentences. Can we meet?”

He played me an audio file in his car in a grocery store parking lot. The principal’s voice, identifiable even through the low fidelity, saying, “We have to control the narrative. We can’t allow the doctor to destabilize the school. The media forgets. We just need to ride the cycle. He knows too much.” He. The counselor. He, who had “disappeared.”

The journalist’s hands shook on the wheel, not because of me, but because he has a daughter. “This goes beyond one school,” he said. “It’s a network. It’s everyone protecting the plaque on the wall.”

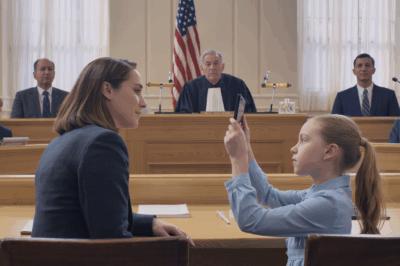

My lawyer took the recording to a prosecutor rumored to be a man whose family photo of three girls on his desk had made him less reckless than his colleagues. He sat with the dossier I had assembled—printouts, screen grabs, an annotated timeline—and he listened the way you listen when your own house lives one street over from the danger. “We’ll move,” he said. “It’ll be glacial until it’s sudden.”

The school wrote a public letter that said they were “deeply saddened” by “unfounded attacks” and “committed to the safety of children” and “already reevaluating our procedures.” The community split. Half wanted to drop their kids at the front door and trust again because trust is easier than vigilance. Half wanted to burn the place down.

My license was put “under review” due to an anonymous complaint about “emotional instability.” My boss asked if I was sleeping. I told her the truth: sometimes. She asked if I had started therapy. I said yes, because if I said no, the conversation would shift into the kind of concern that becomes a memo. I started therapy the next day. I picked a woman who wore linen and didn’t blink when I said, “I think I asked a man with face tattoos to do something I won’t say out loud.”

“Sometimes,” she said after a beat, “we hold the door for the part of ourselves we wish didn’t exist. And sometimes that part carries a child out of a burning house.”

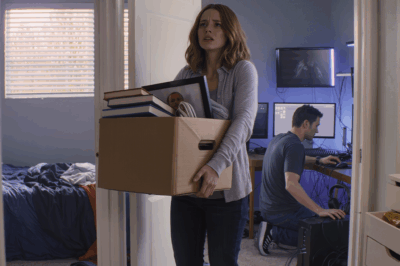

Part IV — The Threat and the Flight

The first direct threat arrived on a Tuesday inside an envelope with a stamp of a lighthouse that felt like a joke. Letters cut from magazines: You’ve caused enough trouble. Stop. It was such a cliché that I laughed, but my hand shook.

Friday, my car door bore a key mark from headlight to trunk. Saturday, a new email: We know where you live. Sunday, a black sedan outside Mrs. Livingston’s home, where my daughter was playing because we don’t do playdates at our place anymore.

My lawyer told us to leave for a while. We went to a cabin rented under a name that wasn’t mine. My mother came, having finally understood the thing she’d been told was “hysteria” was a fire that had burned past polite. She did crosswords at the table while my daughter fed Cheerios to her unicorn and the wind did its old trick with the pines.

On the third night, an envelope slid under the door like a tongue. No return address. One sentence: You are dragging your child into the fire. Stop. My daughter slept in my bed the rest of the week. I held a knife under my pillow and hated every cartoon version of myself that thought weapons made you brave.

We moved again—to a friend’s place with a gate and cameras and a dog that didn’t know how to be quiet. The prosecutor called to say there were warrants for the principal’s devices. The journalist published a story that didn’t use my name but might as well have drawn my face with a crayon. The comments divided exactly as you’d expect: saint and monster, heroine and drama queen, mother and hysteric. I closed the page. I made lunch. I kept moving.

A former teacher met me at a diner with Agnes baked into the carpet and handed me a file folder: memos, policy updates, a complaint she had written and buried in a drawer when the principal told her she’d never work in the district again if she made trouble. I took photos of everything. My lawyer grinned for the first time in months.

Then the call came at midnight. A man’s voice, slick with someone else’s confidence: “Hey, Unicorn Girl’s Mom,” he said. I didn’t know whether to put the phone down or hold it closer. “You think you got one of us, but you touched a web. And you know what the spider does to hands?”

I hung up. I went into my daughter’s room and sat on the floor and watched her sleep and promised the air that if anyone came through the window, I would pull the house down around us before I’d let them through the door.

The next morning, the principal was arrested in a town one highway over for bribery, tampering, conspiracy. She had tried to check into a motel under her sister’s name and left her actual driver’s license on the counter. The mugshot looked like a person who still thought she could talk her way out of a prison made of receipts. It wasn’t my victory, not directly. It was pressure. It was everyone finally looking where the children had already pointed.

Part V — The Flood

Once one story breaks, the others pour out like water from a ceiling with a cracked seam. Mothers called me. Fathers. A teacher who had moved states. A paraprofessional who had raised a complaint, gotten a small settlement, and been told to sign a nondisclosure and keep her conscience on a leash.

The prosecutor called to say there would be a press conference, that it would be messy, that it would help and hurt in equal parts. The journalist asked if I wanted to go on record. I said no; I had a daughter to get to school and a job to keep and a court to appease and a neighborhood to avoid setting on fire.

But I did speak at a town hall where the room split into two colors: people who had been waiting for permission to say what they knew and people who had built careers on telling them to shut up. I told them about the first night. I did not say the word unicorn. I said violation. I said institutional betrayal. I said a phrase I found in a paper years ago that had sat in my mind ever since: “The perpetrator’s best friend is the entitled adult who needs the institution to protect their name.”

The district promised training. The district promised windows in doors. The district promised that two adults would be in any room where a child needed help. The district promised trauma-informed counselors who had been screened in ways that would make the CIA blush. The district promised the moon and then made a nice brochure about the stars.

My daughter began to smile like herself. She still woke in the night sometimes and stood in the doorway like a ghost, and I would lift the blanket and she would slip under it and press her cold feet against my calves and whisper, “He can’t come here,” as if the bed were a sacred place.

She started therapy with a woman who drew feelings as animals and told her that fear is a puppy that needs training and anger is a bear that can learn to dance. I hated how much that helped because I wanted therapy to be as furious as me. But on a Tuesday in June, my daughter handed me a drawing of a unicorn with a sword and said, “She’s a knight now.” I taped it to the fridge like a relic.

My license was reinstated. The hospital gave me a new badge, which is how places say sorry. I went part-time. The rest of the time I answered emails that began I think this happened to my child and ended tell me what to do.

I started writing—not just reports for lawyers and prosecutors, but essays about what mothers do when the world pretends it is safe while it hides knives under pillows. Some magazines said the tone was too angry. Some said it was not angry enough. One printed it with an illustration of a woman holding a torch and a child behind her with a look that said both thanks and I wish you didn’t have to.

Part VI — The Long Year

We moved to a smaller town where the school secretary knows my daughter’s favorite fruit and slips apple slices into baggies with smiley faces drawn on them. I rented a house with a real porch and two locks on the back door and a fence that makes you lift the latch a special way. The dog took to the yard like a letter finally delivered to the right address.

Life didn’t become easy. It became possible. We learned the names of crossing guards. We learned which neighbors return Tupperware and which keep it. We learned who asks kids first before they ask parents. We learned the sound a happy kid makes when they are not trying to be smaller to fit inside someone else’s expectations of quiet.

Sometimes the old shadows visited. A car idled too long. A letter arrived with no return address. A newscaster said the principal’s name and I tasted metal. My daughter traced the scar on the unicorn’s seam where she had hugged it too hard and the thread had given. We sewed it together again on a Sunday and told it to hold.

At the end of that long year, on a day that smelled like chalk and oranges, my daughter climbed into the back seat and said, “Mom, thank you for not pretending nothing happened.”

I pulled into a parking lot and cried because there are sentences you wait your whole life to be worthy of and you never are and you get them anyway.

Part VII — The Web and the Scissors

It turned out the counselor had been moved before. Whispers appeared in files from other schools, notes that sounded like warnings but were written like compliments. The principal’s trial date was set and rescheduled and set again. The counselor remained vanished, a blank the internet poked at every few months when a thread got hot. The man with tattoos never called again. I burned his number and watched the flame flare and die in a kitchen sink that has seen the blood of strawberries and once, infamously, my thumb.

I spoke to parents in church basements and community centers about the difference between privacy and silence. Privacy is a door you close to keep warmth in. Silence is a door someone else closes to keep you out of your own house. I taught them to ask counselors about protocols. I taught them to demand windows. I taught them how to refuse to be soothed by professional smiles. I taught them how to be the problem and then I watched them become it with admiration that tasted like grief.

A journalist wrote a book. He called me “the mother who set silence on fire,” which I find simultaneously corny and correct. He also wrote about the women who tried before me and were dismissed, and I send those pages to my daughter when she is old enough to know the names of the women who fought for her before she existed.

Part VIII — The Question Everyone Asks

“Wasn’t it wrong?” a woman asked me at a Q&A in a library with carpets that never get vacuumed enough.

“You’re asking me about the call,” I said. The room smelled like old paper. I pretended to consider. I had considered for twelve months. “I’m a doctor. I take an oath: first, do no harm. I have dedicated my life to harm reduction. And I made a phone call that harmed someone. I did it because every path the light offered me was blocked by people guarding their own reputations, so I borrowed darkness long enough to clear the way.”

“That’s not an answer,” she said, trying to be kind and failing.

“It’s the only one I have,” I said. “I will live with it. So will my daughter. So will the people who built a school where harm could happen behind a closed door. When you ask me about wrong, ask me about the first wrong. Ask me about the second, when the principal smiled at me. Ask me about the third, when the officer called me hysterical by using other words. Ask me about the one I made after all the others had taught me that right was not available that day.”

Part IX — The Ending You Ordered

You wanted a clear ending. We all do. Here it is, as honest as I can make it.

The principal was convicted on charges of bribery, destruction of evidence, and official misconduct. She cried in the hallway because cameras were there. She will get a pension anyway because systems take care of their own. The district settled with three families in amounts that would not fix anything and drain budgets from art classes. The state mandated windows in every counseling office door by September. The contractor who installed them in our town said he’d never had so many grateful people thank him for doing a thing that should have been done in the first place.

My daughter is ten now. She still sleeps with the unicorn, but sometimes she forgets to bring it on sleepovers, and that’s a victory quiet enough to miss if you don’t know what it means. She plays soccer badly and loves it. She rolls her eyes at me in ways that make me love her more. She tells her friends secrets about crushes and spelling tests and a teacher who laughs like a soda can opening. When she talks about “the bad year,” she does it like it belongs to someone else, and maybe that’s another kind of healing—putting things on shelves where they can be found when needed and ignored when the sun is right.

I practice medicine three days a week and activism the other days and mothering every day. I sleep sometimes. I have nightmares sometimes. I sit on my porch with coffee and listen to a neighborhood that doesn’t know it survived something with me. I plant flowers my mother says will be eaten by squirrels and I plant them anyway.

Do I think about the call? Of course. When sirens pass at night, I think about it. When someone asks me about ethics, I think about it. When my daughter says “thank you for not pretending,” I think about it and then I do not.

If you need me to say I’m sorry, I won’t. If you need me to say I’d do it again, I will. If you need me to offer you a better world where I never had to make that choice, I will point you to a school board meeting and a donation to a journalist’s newsroom and a vote you can cast and a child you can believe. That’s how we build the world where mothers don’t learn to use matches.

Part X — The Light We Carry

On the anniversary of the worst day, my daughter and I drove to the ocean because the ocean is big enough to take it. We wrote words in the wet sand and let the tide erase them. She wrote “fear.” I wrote “silence.” She drew a unicorn with wings. “Pegacorn,” she said confidently. “She flies away from bad places.”

“Where does she go?” I asked.

“Where the kids tell the truth and the grown-ups say okay,” she said, not looking up. “Where the doors are glass and the windows open and the counselor is a nice lady with a rainbow lanyard.”

We stood knee-deep and let the water numb us. The horizon looked like a promise we’re still too tired to make.

On the way home, she fell asleep with her mouth open because children do not care how they look when they’re safe. I watched the road. I thought about the man with tattoos. I thought about the principal. I thought about the detective with the scar. I thought about the journalist who risked his career. I thought about the prosecutor who cried. I thought about Mrs. Livingston, who watched my daughter sometimes with a fierceness I could see from the street. We are a village made of people who learned the hard way to stop being polite when the house is burning.

If you find yourself at the edge of the dark side someday, shaking with a phone in your hand and a child in your house, I cannot tell you what to do. I can only tell you what I did and what it cost and what it bought and how we live now. We sleep. We wake. We hold the line. We tape drawings to the fridge. We demand windows. We point to the closet and show our children how to check it with the light on and then the light off and the light on again. We tell them that secrets that hurt are not secrets; they are lies someone tricked them into holding.

The dark side didn’t swallow me. It singed me. It lit what needed to be seen. Then it went out, and I was left with a different job: carrying a smaller light every day wherever it’s needed—school board meetings, waiting rooms, living rooms, porch steps, court benches, kitchen tables. It’s not dramatic. It’s steady. It’s heavy. It’s enough.

That is the ending: a mother with a flashlight, a daughter who sleeps, a neighborhood that learned to knock on the right doors at the right time, a school with windows in its counseling office doors, a unicorn with a sword drawn in purple marker and taped to a refrigerator in a house with two locks that are mostly habits now.

That is the one time I turned to the dark side. The rest of the time, I chose to stand where the light is, to make it brighter, to aim it, to hold it steady while other mothers find their way to the door.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

“We’re Taking Your Lake House For The Summer!” Sister Announced In A Family Group Chat. I Waited…

“My sister said, “We’re taking your lake house for the summer,” and everyone in my family agreed. They drove six…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes… Part I: The Answer…

When did you FIRST realize that your parents were bad at parenting?

When did you FIRST realize that your parents were bad at parenting? Part I — The Night the House…

HOA Karen Tried to Fine Me for Drinking Coffee in My Front Yard!

HOA Karen Tried to Fine Me for Drinking Coffee in My Front Yard! Part I: The Violation The morning…

My BROTHER got me KICKED out of the house so he could use my room as a game room…

My BROTHER got me KICKED out of the house so he could use my room as a game room… …

MY PARENTS SUED TO EVICT ME SO MY SISTER COULD OWN HER “FIRST HOME.” IN COURT, MY 7-YEAR-OLD ASKED

My parents sued to evict me so my sister could own her “First home.” In court, my 7-year-old asked the…

End of content

No more pages to load