When In-Laws Boycotted My Daughter’s Birthday, I Gave Them an Unexpected Gift

Part 1

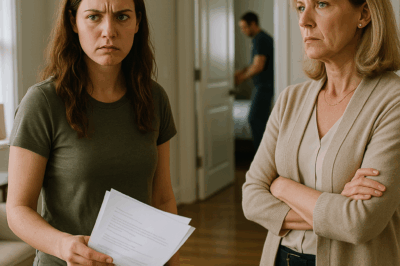

The text from my mother-in-law hit like a slap: We won’t be attending Poppy’s birthday party. I hope you understand that these celebrations are different for girls.

I didn’t throw my phone. I didn’t scream. I pressed my palms flat to the cool quartz of our kitchen island and watched the pale crescents bloom in my knuckles. The afternoon smelled of oranges and dish soap. Outside, our neighbor’s wind chime insisted the world was gentle. Inside, a six-year-old’s joy had just been measured against her chromosomes and found wanting.

“Mommy, is Abuela coming to my party?”

Poppy stood in the doorway clutching her stuffed elephant by one satin ear. Her curls were a halo of sleep. I opened my mouth and found that I had no truthful sentence that wouldn’t crack her heart. Before I could try, the front door opened and Caleb strode in, loosening his tie. He looked at me, really looked, and his expression sobered.

“What happened?”

I handed him my phone with fingers that had stopped feeling like mine. “Your mother happened. Again.”

His eyes skimmed the message. The muscle in his jaw worked. “I’ll call her.”

“Don’t.” I watched Poppy retreat, her exaggerated tiptoes an old habit from the years when we still believed we could keep adult storms from spilling into the children’s weather. “This isn’t the first time and it won’t be the last. Remember Christmas? Your brother’s boys got gaming consoles. Our daughter got a coloring book.”

“They’re… old-fashioned,” he said, rubbing the back of his neck. It’s what he always said, the phrase worn down to something like apology. “They attended Nico’s party last month. They helped with the carnival rentals. I know.”

“Old-fashioned?” I laughed, and if bitterness were a color, it would have stained the kitchen tile. “They threw a mini carnival for your nephew. But their granddaughter? She’s not worth the drive.”

Caleb ran his fingers through his hair, the way he does when the space between his wife and his family turns into a tightrope over a bonfire. “Let me talk to them. Maybe if I explain—”

“Explain what?” I lowered my voice because Poppy was humming in the next room. “That their granddaughter deserves to be celebrated? That she notices when Abuela hugs her cousins longer? That last week she asked me if Abuela likes boys better than girls?”

The pain in his eyes matched mine. I didn’t need pain. I needed a decision.

“I’m done,” I said. “I’m done watching our daughter shrink to make their world feel bigger. This birthday? It’s going to be something they regret missing.”

My phone buzzed again: Prince—Caleb’s brother. Mom told me about the party. Try to see it from their perspective. Girls don’t carry on the family name.

“Your brother’s perspective can go straight to hell,” I said, my smile too stiff to be safe. “I need you to choose, Caleb. Right now. Are you with your daughter or with them?”

“That’s not fair,” he said without heat. “They’re my family.”

“What are we?”

Before he could answer, Poppy raced back in, waving her hand-drawn invitation. “Mommy, can I show you my drawing for the party?” She spread a sheet of paper on the island—a riot of crayon color. A circus tent tipped with stars. A lion mid-roar. Elephants with heavily lashed eyes. Her joy was earnest enough to make the room tilt back on its axis.

“See? There’s going to be a lion. And elephants!” She pointed with a flourish only six-year-olds and magicians get right.

Something clicked into place. This wasn’t about revenge anymore. It wasn’t about fighting smallness with smaller. It was about building a party sized to the measure of my daughter’s worth. She would not learn to calibrate her joy to someone else’s narrowness. Not at six. Not ever.

I picked up my phone and dialed Angela.

“Hey, trouble,” she said by way of greeting. “You surviving the pre-party sugar tornado?”

“Remember that event company you worked with last summer?” I asked. “The one that did that celebrity kid’s party? I need their number.”

“What are you planning?” she asked, instantly alert.

“Something big,” I said, watching Poppy color the ribbon on an elephant’s hat with careful stripes. “Something magical. Something that makes it obvious exactly what the Salazars are missing.”

“I’m in,” she said. “Text me your budget. And don’t you dare say ‘modest.’”

“Caleb,” I said as I hung up. “I need you to decide where you stand. Because this party isn’t just a party anymore. It’s a statement.”

He looked at Poppy, at me, at his hands. He nodded. “With you. With her. Always.”

“Good,” I said, and if my voice shook, it wasn’t fear. It was the tremble of a fuse being set.

“This is insane,” my mother said, delight disguising itself as disapproval. Her name is Adeline. She can negotiate a florist into agreeing daisies are peonies if you let her.

“We’re calling in favors,” my father—Frank—said, already writing a check with the flourish of a man who has been waiting for this moment since the day he became a grandfather. “No one messes with my granddaughter.”

We spread plans across their dining table: a tent the size of a small cathedral; a stage; aerial rigging; cotton candy machines; a real calliope because my father has a sense of humor that can only be cured by spectacle.

“We won’t need a tent that big,” I said weakly. “We invited fifty kids.”

“People are going to invite themselves,” Angela said, bursting in with fabric swatches and a laptop. “I already posted a teaser. The hashtag is #MsBigTop.”

“Wait, who’s Ms.?” I asked.

“You,” she said. “But the internet thinks it’s Poppy. Double win.”

My phone pinged. “You won’t believe who just RSVPed,” Angela said, wiggling her eyebrows. “Marcel Price’s assistant. As in Marcel Price, the media mogul. Twins. Six. He ‘heard’ we’re building the most magical party in the city.”

“How did he hear?” I asked.

“I may have mentioned that elephants were involved,” she said with the kind of smile that gets people into VIP sections and out of tickets. “Speaking of—Adeline?”

Mom had her phone to her ear. “James? It’s Adeline from The Conservatory. Remember the gala with the peacocks? Yes. I’m calling in that favor. How do you feel about bringing your girls to a birthday party?”

“Girls?” Poppy said, appearing like she’d heard candy sing. “What girls?”

“Rose and Daisy,” Dad said, already scrolling through his camera roll to show Poppy a picture of two gentle giants he’d met once at a fundraiser. “They’re elephants.”

Her eyes went huge. “Real elephants?”

“Real,” Mom said, covering the mouthpiece with one manicured finger. “If James can get the permit and if we promise to do this safely, Summer.”

“Safely,” I said, meaning it. Joy that costs someone else their dignity or their creatures their comfort isn’t joy. It’s theater. We would not do theater. We would do magic.

The veteran party planners and time-serving vendors in our orbit turned the house into a staging ground for delight. Angela posted a countdown. The hashtag seeped into corners of the internet I didn’t know existed. With Marcel Price’s twins on the list, RSVPs multiplied. Caleb raised a practical eyebrow at the guest count. Dad wrote another check.

“We’re leasing the field behind the house,” he said. “And the church lot for parking.”

“And a generator,” Mom added. “I will not have the popcorn machines die in Act One.”

“What’s Act Two?” I asked.

“The opening number, obviously,” she said, as if we had always discussed our lives in acts.

Poppy practiced in the living room to music from a Bluetooth speaker and Miss Rachel’s voice in her head. Her ribbon traced arcs of purple through the air that felt like a bow across the last six years of her life. Sometimes people mistake sparkles for frivolity. But when she danced, I could see the muscle memory of every time she had asked whether Abuela loved boys more. I could see her self-worth recalculating itself on a stage built for her.

“Invite your whole class,” Dad said when she ran out of paper for her list of names. “Invite the class next door.”

“I want to invite Maria and Sophie and Lucas and Miss Rachel and also…the elephants,” she said.

“The elephants have a hard stop at nap time,” Angela said. “But we’ll write them a proper invitation.”

Prince texted again: Mom says you’re turning this into a circus just to spite her.

“Tell her she hasn’t seen anything yet,” Dad said, without looking up from his spreadsheet labeled Cotton Candy Logistics.

Caleb came home each night with vendor confirmations and a bruise of stress on his brow. Between calls to rental companies and texts from his mother, I watched him become a man who understood that love is not a spectator sport. When Prince sent a screenshot of Yolanda’s group chat with a circle around the words Girls don’t carry on the name, Caleb put his phone down and held my face in his hands. “I should have stood up sooner,” he said.

“Yes,” I said, meeting him where he was. “And you’re standing now.”

The day before the party, our yard turned into a fairytale. The tent rose up like a grounded cloud—red and white stripes stitched with lights. Workers hung chandeliers in the oaks like they were bare shoulders. The air filled with popcorn and spun sugar and possibility. When James’ truck pulled in with Rose and Daisy, the street went from curious to carnival. Children pressed against fences. Grownups tried not to, and failed.

Marcel arrived early with the kind of low-slung car that makes neighbors forgive people their success. He stepped out with twins who wore expressions that said they’d seen everything twice and still considered delight a useful currency.

“We came to look,” Marcel said, and shook my hand like a man who knows exactly how often his handshake gets asked for. He watched Poppy offer Rose a carrot and whispered to his assistant, who typed.

“She has presence,” he said. “Most kids perform at you. She performs with you.”

“She loves people,” I said. “Even when people are not…lovable.”

He tilted his head, amused. “Are you describing your in-laws or my industry?”

“Both,” I said.

He laughed. I watched his twins watch my daughter and felt something loosen in my throat that had been tight since Yolanda’s text. Sometimes you measure your wins by the things you don’t have to say.

Cameras arrived. The smell of microphones is an odd thing to admit. It smells like dust, fabric, breath. It smells like a story being measured for its angle. When the first camera pointed at Poppy, I felt my body go somewhere ancestral: shield, shield, shield. “We won’t film anything without release forms,” Marcel’s assistant said, gentler than necessary.

“That isn’t my worry,” I said. “She’s six.”

“It’s mine,” Marcel said. “I have six-year-olds at home. We’re here because I’m a father. The cameras are along for the ride.”

Later, we would find out Marcel’s twins had told him in the car that they were tired of shows where girls existed mostly to have things done to them. They wanted to watch a girl doing things—and making adults catch up.

A familiar SUV crawled past the house. Prince. He didn’t stop. I felt the old urge to wave and the newer one to let absence teach what presence hadn’t. Let them watch. Let them count the elephants and the cameras and the joy and realize that influence requires investment. Let them understand that you can’t withdraw from a childhood you never deposited into.

As dusk fell, Poppy showed Marcel’s twins her ribbon moves. Rose and Daisy snored like old men in a warm room. The camera crew caught everything with the quiet hunger of people who know when they’ve gotten lucky. Caleb closed the back gate and stood beside me, smelling like stress and gratitude.

“Your mother will say we did this to spite her,” I said.

“We did this because she hurt Poppy,” he said. “If spite were a party, it wouldn’t look like this.”

“Good,” I said. “Help me figure out where to put the trapeze.”

He blinked, then laughed and shook his head. “How did I underestimate your capacity for wonder?”

“You only know my rage setting,” I said. “This is my wonder setting.”

The morning of the party was absolute joyful chaos. Greeters at the gate. Acrobats warming up. Vendors hauling bags of ice. The MC ran through his script. The concession stands exhaled steam. Volunteers pinned nametags to small chests. I pinned down a halo of curls long enough to fix a rhinestone tiara.

“Is it straight?” Poppy asked, forehead wrinkled.

“It’s perfect,” I said, and meant more than the angle of her crown. “If you forget any steps, smile like you mean it and make up a new one. Real performers borrow from the present.”

“Like Miss Rachel says,” she said. “Second chances take full attention.”

“Exactly,” I said, wondering when my six-year-old had become a philosopher.

Angela burst in. “You need to see this.” She held up her phone—our street on a local news live feed. A block away, cars lined the curb. In one, Yolanda sat in the passenger seat with her hand over her mouth. Next to her, Prince stared ahead like a man reading a language he doesn’t speak. Cousins’ faces hovered in other windows. Let them watch, I thought again. There are truths that refuse to be delivered through arguments. They require windows.

The tent hummed. The announcer cleared his throat. The lights dimmed and the sound of drums rose. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he sang, and the words were as corny as they were correct, “welcome to Poppy’s Big Top!”

Trapeze artists floated. Jugglers flicked knives and then passed them to each other like gossip. A contortionist made adulthood seem overrated. James led Rose and Daisy into a circle. Children squealed. Adults squealed. It was a squeal symphony. Then the music shifted to the one Poppy knows best. She stepped through the curtain in lavender sequins and purple ribbon and breathed into the space like she’d been filling rooms her whole life.

She danced. She told the story of a child building a tent in a world that told her she didn’t need one. She spun grief into arcs of grace and fear into footwork. She finished with a split that made a woman in the third row cry as if blood were leaving her in some old shape and coming back different.

The crowd stood. Camera flashes popped like popcorn. Marcel’s twins jumped up and down. Marcel didn’t hide his grin. “We need to talk about a screen test,” he said to Caleb, to me, to the part of me that wasn’t sure I’d ever get to enjoy good news without bracing for shame.

And then—they arrived. Yolanda at the gate, cheeks wet. The rest behind her, uncomfortable in the way people are when they are losing a story they’ve told themselves about the world.

“Please,” she said—soft, nothing like the woman who’d texted me about family names. “Please let me see my granddaughter.”

“Now you want to see her,” I said. “Now that there are cameras.”

“I was wrong,” she said, and the words sounded like they were new on her tongue. “I was wrong, Summer. I was wrong. I stood on the corner and watched her dance and I was wrong.” Her voice broke. “I don’t know how to fix it.”

“That isn’t my decision,” I said. “It’s Poppy’s.”

And fate—or Miss Rachel’s choreography—brought Poppy to my side. She stopped when she saw Yolanda. Children are clear. They understand boundaries better than adults who vote.

“Abuela,” she said, quietly.

“Mamore,” Yolanda said, using the nickname only Poppy loved. She knelt. “I’m so sorry. I missed things. I believed things. I want to be here now. If you’ll let me. If your mother and father will let me.”

Poppy looked up at me. Then back at Yolanda. “You missed my other party,” she said, matter-of-fact. “Don’t miss anymore, okay?”

Yolanda cried in a way that made television producers salivate and grandmother hearts split. She nodded. “Never again,” she said into Poppy’s hair. “Never again.”

Marcel materialized beside me, conspiratorially quiet. “That,” he said, “is why cameras exist.”

“Find another story,” I said. Then, because the look he gave me was not predatory so much as paternal, I reconsidered. “Maybe later.”

We ate cake. Children rode elephants in loops that were more ceremonial than circus. Poppy taught Marcel’s twins how to ribbon dance with paper streamers because they were lighter and less apt to give a child a concussion. The acrobats ate sandwiches. The camera crew caught laughter and light and the way pride looks when it learns a new language.

When the last guest left, the tent breathed out. Angela toed off her shoes and collapsed onto the stage. Dad turned off the calliope and wiped his eyes. Marcel shook Caleb’s hand and said, “Tuesday, screen test. Bring the ribbon.”

That night, after everyone had gone, I stood in the yard under the strings of lights and breathed. Caleb slid an arm around my waist. “I know you wanted revenge,” he said.

“I wanted celebration,” I said. “Turns out they’re not the same.”

“They can look similar from a distance,” he said.

“Not up close,” I said, leaning into him. Poppy slept inside with a stuffed elephant tucked under her arm and rhinestones still in her hair.

And down the street, in a house that had been built out of tradition and teeth, a grandmother stared at her phone through a night that would last exactly as long as it takes to choose different.

Part 2

Three days can turn a life. The first one you blow balloons and call vendors. The second one you watch your six-year-old stand on a stage and the truth rearrange itself around her. The third one, the doorbell rings and success arrives in a manila envelope with Marcel Price’s logo and eighty-three pages of contracts.

We spent the morning around our dining table with coffee and caution and a highlighter that ran out of ink. Marcel’s assistant explained residuals like a math teacher with patience. The clause that made me unclench my jaw was the one that said School First in all caps. When you’ve waited for your child’s worth to be allowed, paperwork looks like prayer.

“Do we want this?” Caleb asked.

“I want what lets her joy be her own,” I said.

“And if that’s on television?”

“Then television can come to the table,” I said. “Not the other way around.”

I didn’t want my daughter to become the family’s savior or its scapegoat. I wanted to build a bridge where tradition could walk toward the future without losing its shoes.

Yolanda arrived with a gift bag and an expression that looked new because it didn’t have pride pretending it was principle. From the bag she pulled combs—silver, delicate, etched with dancers—and photographs of a young woman with strong arms and a daring chin. “Your great-great grandmother,” she said to Poppy. “A ballerina in Mexico City. I never told anyone because my mother taught me that performing wasn’t respectable. I was wrong. I thought tradition meant forgetting what made us move.”

Poppy reached for the combs and then stopped, looking to me, to Caleb, to some internal rulebook she keeps. “Are they fragile?” she asked.

“Yes,” Yolanda said. “And strong. Like you.”

We put them in her hair and watched a mirror turn a child into a lineage.

The screen test studio smelled like fresh paint, hairspray, coffee. Poppy took it in the way she takes in new classrooms—spine straight, eyes open, nervousness translating into behavior instead of meltdown. “Ready?” I asked.

She nodded like a dancer. “Ribbon first.”

She did the ribbon first. Marcel nodded to his camera crew. The ribbon arcs caught light like truth. Then she did lines with a boy named Tommy Turner—a pro at eight, if that makes sense. They did improv about a circus behind a grocery store. Poppy said, “The lettuce is the audience,” and I fell a little in love with my child’s brain.

Marcel turned to me after and said, “We want her. Not just for the show we have. For the one we don’t know we’re making yet.”

“Can we call it Poppy’s Grand?” Poppy asked, overhearing because she is her mother’s daughter.

“What would it be about?” Marcel asked, playing.

“About me and Abuela,” she said, as if the answer were obvious. “About how I dance and she tells stories.”

Marcel smiled at me in a way that felt like permission. “We’ll call you,” he said, and meant before dinner.

He called with a contract that said Pilot + Full Season Option and Creative Consulting: Yolanda + Summer and Educational Partner: Salazar Cultural Center because the world we built in our yard begged for a home.

“I’m not signing to spite my mother,” I told Caleb that night.

“I know,” he said. “You’re signing because you believe children can hold tradition in one hand and joy in the other.”

“Exactly,” I said. “And because I believe Yolanda can learn to use both hands, too.”

“You are very generous,” he said, kissing my forehead.

“I am very practical,” I said. “Revenge can’t get you a grant. Cultural centers can.”

We opened the Salazar Cultural Center in a storefront space that used to be a furniture store and then a church and then a storage facility. We painted the walls a yellow that looks like morning. Yolanda curated a Heritage Hall with photos and recipes and stories scribbled on index cards in three languages. I wrote a bulletin board full of Know Your Rights flyers in the hallway to the bathrooms. Angela designed logos that made the building look like it had always been this.

We built two dance studios with sprung floors and mirrors that kids kiss when they think no one is looking. We filled a closet with ballet slippers sorted by size and a stack of white shoes we dyed brown because quite a few of our students have feet that were not part of the original business model for ballet. Miss Rachel set up a scholarship fund with Dad and Mom’s checks. Parents brought tamales and empanadas and rice krispie treats because tradition cannot be taught hungry.

Marcel’s crew filmed quietly, like librarians. They caught Poppy teaching Tommy how to say zapateado and Tommy teaching Poppy how to land a joke so the mic picks it up but the audience thinks it’s a secret. They caught Yolanda figuring out how to do a plié with new knees and Miss Rachel crying in the hallway because she’d never seen her separate worlds meet and not argue over the bill.

The pilot aired on a Tuesday at 7 p.m. It was about a girl who uses dance to understand her family and a family who uses love to understand itself. It trended in places we didn’t know cared about trend. The comments were not all nice because this is the internet, but enough of them were that I cried on the couch and did not hide it from Poppy.

“Why are you crying?” she asked, climbing into my lap.

“Because you are beautiful,” I said.

“That makes you cry?”

“Yes,” I said. “And because other people see it.”

“They don’t all see it,” she said, because she is not naive.

“No,” I said. “But they don’t have to. Enough is enough.”

Good Morning America called. Bring Poppy and Abuela. Yolanda practiced walking in heels and saying “representación” in English. We flew to New York. Poppy danced in front of a skyline that didn’t know it had room for a six-year-old. The host cried. Yolanda cried. I laughed into my hands the way you do when you don’t know what else would hold you.

We came home to a real letter—a paper one with a stamp—from Yolanda’s sister in Mexico City. I watched the segment. I never understood. I was taught a narrowness I mistook for faith. Please send me the museum link when the Cultural Center opens an exhibit. We passed the letter around the table and toasted with horchata because tequila would have been too on the nose at noon.

The first season shot across months that wore me out in ways no party planning had. We learned what call time means and how to say no to things that looked like opportunities but were actually obligations disguised as favors. Poppy learned to ask, “Who owns this footage?” and “Will I still be able to eat my snack?” We called a child labor advocate. We called a lawyer whose office smells like paper and principle. We called Miss Rachel when the set felt too adult.

Yolanda opened the Cultural Center’s doors every morning at nine. She greeted kids by name and put her phone in a basket that says Manners. She also took a beginner ballet class, which might be the bravest thing I’ve seen a sixty-year-old woman do in public. She hung a black-and-white photograph of her grandmother in the Heritage Hall and told children stories about a Mexico City stage and a girl who defied a father who defied a grandmother who would have defied God if she’d had the words.

We built an afterschool program where kids could finish math and then pirouette. We built a Dad & Me class because fatherhood looks better in motion. Prince signed his boys up. He sat on a metal folding chair and watched them try pliés and laughed until he had to stand to stop laughing.

One afternoon, Poppy dragged me by the hand to the Hall. “Look,” she said. There, next to some program flyers and a notice about a tamale sale, hung a card written in a looping script: Thank you for letting me change. —Yolanda She’d copied an old photograph of herself at twenty-two with hair down to her waist and pasted it next to a new one of her teaching a line of small girls how to curtsy.

“You kept it?” I asked.

“She asked,” Poppy said. “She said second chances need witnesses.”

We launched Poppy’s Grand with a live special at the city theater. The lobby smelled like roses and popcorn. The mezzanine was full of executives who wear matching smiles. The balcony had my parents and Angela and Miss Rachel and a lot of people who believed the world can be rearranged with sequins.

The special mixed clips from the show with live performances. Yolanda and Poppy danced together in a piece that Miss Rachel titled Inheritance. It began with Yolanda alone under a single light performing small careful steps, the way you test a floor you don’t trust, and ended with Poppy skipping across the stage on pointe—which she is not technically old enough for, don’t @ me—and Yolanda following with a flourish that said age can be an instrument, not an obstacle.

Marcel announced a foundation—the Poppy’s Grand Initiative—to fund arts education in neighborhoods where budgets think creativity is extra. Caleb spoke into a microphone with a hand that didn’t shake and said, “We’re here for the kids who are told there isn’t a stage for them. We’re building stages.”

Prince came onstage with his sons like a man who has been trying on humility and found that it is not a sweater; it is a skin. He did not apologize into the mic because public apologies are frosted like cakes. He apologized in a side hallway to Poppy and me and then to Yolanda, who cried and said, “I am trying,” and he kissed her forehead like he did when he was six and thought band-aids were magic.

After the show, a woman in a gray suit with a lanyard handed me a card. “National distribution,” she said. “Let’s talk.” I put it in my pocket with a hair tie and a lollipop wrapper because my child needed my hands more than business did.

We went home to a house that had been a circus and then a set and now was just a house again. Poppy put the silver combs on the dresser and said, “We shouldn’t lose them.” I said, “We won’t.” Caleb brushed glitter out of the couch with a lint roller that looked defeated.

“Do you miss the part where you wanted revenge?” Angela asked later, when we sat on the back steps with our feet in the dew.

“No,” I said. “I don’t miss being angry. I feel… awake.”

“You started a revolution,” she said, not looking at me because looking at someone when you compliment them can make them reject it.

“Poppy did,” I said.

“Sure,” she said. “Okay.”

At the Cultural Center’s grand opening, a line curled around the block. A news van. A mariachi band. Miss Rachel crying again. Yolanda stood at the door and hugged people in a non-Latina way that made me laugh. The Heritage Hall had new photos—kids in paper costumes, elders with ledgers of recipes, Poppy holding a girl’s hand and pointing to the silver combs under glass.

“Does it feel like revenge?” Angela whispered.

“It feels like home,” I said.

Poppy and Tommy led a demonstration class. Yolanda showed a little boy how to hold his hands in first position and then congratulated him for trying, which is more than my childhood ever taught me to do. Prince’s boys asked if they could learn guitar. A grandfather offered to teach them. A mother wrote me a note that said I never knew I was allowed to want this for my kids.

Good Morning America did a follow up. They filmed Poppy teaching Yolanda a TikTok dance and Yolanda teaching Poppy a waltz step from a family wedding in 1978. The internet called it intergenerational excellence because the internet gets it right sometimes.

We hung a bulletin board in the lobby titled Second Chances. People pinned photos next to sentences: I apologized to my daughter for believing things I should have questioned. I signed up for adult ballet. I brought my son to Folklórico. I stopped calling my mother every time I needed to feel right. Yolanda taped up a picture of herself in soft pink ballet slippers, smile wide enough to be ridiculous, and wrote: I learned a split. Underneath, Poppy had drawn a star.

On the first anniversary of the party, Poppy insisted we reenact the ribbon dance in the tent we rented mostly because Dad wanted to make hotdogs for one hundred again. Yolanda stood at the edge of the circle, a reflective smile on her face like she was watching a house she’d built get a new wing. Marcel called to say Season Two was greenlit. Miss Rachel announced a scholarship in Yolanda’s grandmother’s name. Angela orchestrated a balloon drop that somehow did not terrify any toddlers.

Yolanda pulled me aside during cleanup. “I wanted to hate you,” she said, without the usual sugar. “When you didn’t answer my calls. When you stood at the gate and made me talk to Poppy. I wanted to hate you. It felt easier than changing.”

“And?” I asked.

“And I am so grateful you didn’t accept easy.”

“I didn’t,” I said. “I accepted honest.”

We stood in the yard under a string of lights that had become the architecture of our life. The elephants were back in their pastures. Rose and Daisy had become legends for toddlers and a metaphor for me. The tent glowed like a memory and then deflated like a lung releasing a held breath as the crew began to pack it. Poppy ran by with Tommy and Prince’s boys and someone’s poodle, and Yolanda laughed like a woman who hadn’t forgotten how.

“You gave me a gift,” she said.

“I didn’t invite you to the party,” I said.

“No,” she said. “The other gift. The one where you let me change.”

I thought back to the text that started all this—We won’t be attending. I thought about how soft “no” can be when it is wielded by someone who doesn’t understand what it can build. I thought about how my own “no” had become scaffolding and then stairs.

Sometimes the best gift you can give people who hurt you is not what they expect. Not a spectacle designed to cut them. Not a silence designed to starve them. Sometimes the best gift is the chance to grow—and the space to fail at it without taking you down with them.

We closed the gates and the last light. Poppy fell asleep in the backseat holding her stuffed elephant, the silver combs safe on the dresser at home. Caleb reached for my hand at a red light and I let him, because keeping score is not the same as keeping house.

When we pulled into our driveway, we could see through the kitchen window the remains of a circus—ribbon tape on the floor, a rhinestone, a glitter footprint that would haunt me for a week. I unlocked the door. The house smelled like sugar and clean sweat and lemon—things you can’t despise unless you’ve never been loved by people who smell like those things.

“Mommy?” Poppy mumbled from her car seat. “Can Abuela come to dance class tomorrow?”

“If that’s what you want,” I said.

“I want to show her the new move,” she said, and fell back into sleep.

We carried her inside. We put her to bed. I stood in the doorway for a long time, looking at a little girl who had brought a grandmother to her knees and a network to their senses. Angela texted a photo of the Cultural Center’s bulletin board. The newest card said: I apologized to my granddaughter for believing the wrong things. Then I learned a split.

I set my phone face down on the counter and listened to our quiet. It sounded like laughter that hasn’t happened yet. It sounded like forgiveness built in layers, not granted in one dramatic moment. It sounded like a life you make when you decide to stop attending other people’s versions of your story.

When in-laws boycotted my daughter’s birthday, I did not give them the party they demanded. I didn’t even give them the party they deserved. I gave my daughter a stage. I gave my mother-in-law a chance. I gave my family a movement. And in the lights and the music and the small brown girl who danced like she trusted the floor, I found the only gift that had ever mattered.

We didn’t get even.

We got bigger.

END!

News

My Cousins Mocked Me—Then Learned I Inherited Grandma’s $8.2M Estate. ch2

My Cousins Mocked Me—Then Learned I Inherited Grandma’s $8.2M Estate Part 1 “Oh, look. It’s the spinster with cats.” The…

My Family Mocked Me for Taking a Law Course—Until I Faced My Brother in Court. ch2

My Family Mocked Me for Taking a Law Course—Until I Faced My Brother in Court Part 1 I walked into…

Mom Said I Owed Her Half My $4.2M—Then She Let My Abusive Ex Stay in My Guest Room. ch2

Mom Said I Owed Her Half My $4.2M—Then She Let My Abusive Ex Stay in My Guest Room Part 1…

At Noon, I Came Home to Check on My Sick Husband—And Overheard the Secret That Destroyed Everything. ch2

At Noon, I Came Home to Check on My Sick Husband—And Overheard the Secret That Destroyed Everything Part 1 I…

I Went Into Labor at Night, My Husband Ignored My Calls—And the Wrong Text for Help Changed My Life. ch2

I Went Into Labor at Night, My Husband Ignored My Calls—And the Wrong Text for Help Changed My Life Part…

My Mother Called After Years to Invite Me to a Family Reunion: ‘You’ve Proven Yourself Now’ ch2

My Mother Called After Years to Invite Me to a Family Reunion: “You’ve Proven Yourself Now” Part 1 Success tastes…

End of content

No more pages to load