When I Inherited My Grandparents’ $900K Estate, I Quietly Moved It Into…

Part One

My name is Aiden. I’m thirty-two, and for most of my life I was the person you could count on to be quiet, agreeable, and available—the human equivalent of “default settings.” You needed a ride at dawn? I was there. You needed a weekend of heavy lifting? I brought pizza and didn’t complain. Someone forgot whose turn it was to be responsible? The room turned toward me like flowers to the sun. That’s who I was.

Until my grandparents died.

Grandma went first—pneumonia after a winter where the cold got into more than her lungs. Grandpa followed a year later, not from anything dramatic, but because sometimes your reason for staying wears your sweaters and smiles from frames on the wall, and when she packs them away, so does your will to keep showing up. They were the kind of people who lived within their means when their means were tight, and kept doing it after they weren’t. They ate leftovers like it was an ethical stance and ironed foil to reuse it. They loved me in two languages—English and practicality.

I was their person. Not because I was the favorite but because I showed up. I took them to appointments, learned their pharmacy’s hours by heart, deciphered Medicare letters written in hieroglyphics. I fixed the Wi-Fi by turning it off and back on and then got the lecture about how “the internet is in the air now.” I learned which flowers the neighborhood cat refused to dig up. I sat with Grandpa in the den and read, sometimes out loud when the print blurred, sometimes in silence because being alone together is its own kind of generosity.

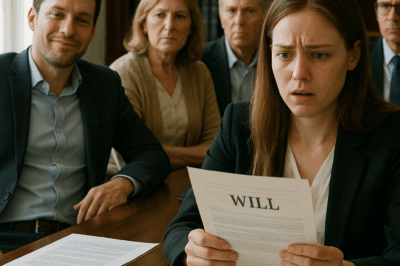

I wasn’t surprised, then, when the will named me. The house. The liquid savings. A modest stock portfolio that turned out to be not that modest after all, thanks to a boring index fund and the magic of compounding interest. Altogether, just under nine hundred thousand dollars. The number sounded like something from a headline about other people. In the attorney’s office, it sat between us on cream paper and made my palms sweat.

What surprised me was the look on my mother’s face as she stared at that paper—a tight-lipped twist that lived somewhere between offense and calculation, like a person who spots something they think they should have already owned. She didn’t say Congratulations. She didn’t say They loved you. She said, later in the parking lot, “Well, your brother was always Grandpa’s favorite,” as if that was an explanation, or a warning.

Tyler is three years younger than me and the human version of a well-lit stage—flashy, loud, charismatic in the way that makes waiters remember his name and landlords forget late fees. He is “next chapter loading” as a personality. He’s had more “sure bets” than my grandparents had birthdays, and I have paid for too many of them in interest and the loss of believing people when they say they’ve changed. He can lie to your face and still leave you wondering whether you misheard him. He once put a credit card in our mother’s name and called it “a surprise.” He once borrowed a friend’s car and returned instead with a story about a tow truck and a misunderstanding. He is the kind of person my mother calls “just figuring things out” and the kind of person I used to call “my problem.”

I am not that person anymore.

The house was the big piece—three stories of red brick and clean lines, tall windows that made the morning a stage, ivy climbing like handwriting along the east wall. A dent in the old banister from the day my grandfather came back from the war and carried my grandmother up the stairs because that’s what the movies told him to do. It was a historic property, officially and intimately. Every house around it had been gutted and flipped as the neighborhood values exploded. My grandparents never sold. They said houses are what you hold on to so there’s a place for people to come back to. Now it was mine.

I didn’t move in. Not right away. I kept my apartment across town and put the Victorian on a diet of deep breaths and dust cloths, getting to know it the way you get to know someone old: by listening for the creaks that mean comfort and the ones that mean trouble. I hired an estate attorney who spoke “future-proof” without sounding like a fortune teller. I had the house appraised (too high for taxes, not high enough for flippers) and sat with a wealth manager long enough to learn what I didn’t know and how not to ruin what my grandparents had built by dying politely.

And then I did the quiet thing that changed everything.

I moved everything—house, savings, shares—into an irrevocable trust, the legal equivalent of putting your most precious thing in a safe only you have the combination to, then welding the safe shut. Not just the title—utilities, insurance, property taxes too. I put them all under a holding company with a name so boring it looked made up. It cost extra. I didn’t care. I knew my people. I knew the storm I saw brewing in the corner of my mother’s mouth.

I told no one. Not Tyler. Not my mother. Not the neighbor who peered over the hedges on Thursdays and collected everyone’s gossip like coupons. I just kept showing up with bags of mulch and sat on the porch with a thermos like I’d always done.

For a while, it stayed quiet—too quiet in that way where you can hear your own heartbeat and the faint hum of someone else’s plans being made. Tyler posted vague inspirational nonsense on his socials. “Big things coming.” “Next chapter loading.” My mother dropped phrases like, “It’s such a burden for one person to handle everything” and “It would be more practical if”—always if, never how—“things were shared.” I changed the subject. I brought her a pie.

And then the storm announced itself.

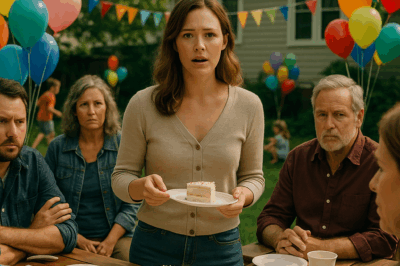

It was a Saturday in late May, bright enough to make the dust look like confetti in the sunlight. I was pulling weeds along the walkway—proving to the planet one fistful at a time that I was not above manual labor—when my mother’s car turned into the driveway. Tyler climbed out first, sunglasses, grin, the kind of walk you use when you pretend to be arriving somewhere you’ve been invited to. My mother followed, clipboard in hand, smile shaped like a ribbon-cutting.

“Hey man,” Tyler said, clapping my shoulder too hard. “Got some news.”

I stood. Brushed dirt from my hands. Raised an eyebrow that felt more like armor than facial expression.

“We spoke to a lawyer,” my mother said, stepping forward. “It turns out the house should have gone to both of you. Your grandfather didn’t update his will properly after your grandmother passed. But don’t worry—we handled it.”

“Handled what?” I asked.

Tyler pulled a folded paper from his back pocket like a magician who still believes his own trick. “We had the title transferred to my name,” he said. “It’s already done. You’ll need to be out by Friday. No hard feelings.”

From the sidewalk, the house creaked in what I swear was amusement.

I looked at them—my mother’s mouth tight, Tyler’s grin wide enough to trip over. My heart didn’t race. My blood stayed where it belonged. I smiled the kind of small smile that makes people nervous because it doesn’t match anything they expected.

“You really think I’d let that happen?” I asked.

“It’s already happening,” Tyler said, as if conjuring something makes it real.

“We’re not trying to be cruel,” my mother added in her best soft-voice disguise for manipulation. “It’s just practical. Tyler can manage the property. Maybe flip it. You’ve got your own place anyway. This way, everyone wins.”

“Got it,” I said.

Then I went inside, locked the front door, and made two phone calls.

They came back on Monday with a rented moving truck and the kind of laughter you use when you want strangers to know you’re in the right. Tyler sat in the passenger seat with a coffee and the confidence of a man who’s never read a statute. My mother threaded the movers toward the front steps with her clipboard held like a passport. They stopped when they saw the porch.

I was there, arms crossed, next to a tall man in a navy suit with a badge clipped to his belt and a folder under his arm with the trust’s boring name printed on the tab.

“Are you Tyler Green?” the man asked when we stepped down.

Tyler frowned. “Who’s asking?”

“I’m with the county office of property records,” he said. “My name is Mr. Leven. I’m here on behalf of the legal trustee of the East Thorn Hill estate.” He gestured toward the house with the folder. “I have documentation showing this property has been held in an irrevocable trust since April of last year, with management vested in the trustee, Aiden Green. Any claims made regarding ownership since that date—including the fraudulent title transfer filed last week—are not just invalid, but criminally prosecutable.”

“Fraudulent?” Tyler sputtered, color draining like someone had opened a valve. He looked at my mother. “What is he talking about?”

“There must be some mistake,” my mother said. “We had a lawyer look at the old deed. It was still in your grandfather’s name. We assumed—”

“You assumed wrong,” I said. I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t need to. “The deed’s in the trust. That’s why you couldn’t find it the way you thought you would. You filed a title through a sketchy online registry in another state using a fake notary and Grandpa’s outdated paperwork. You didn’t handle anything. You attempted to steal my home.”

Mr. Leven consulted his folder with the calm of a person who never needs exclamation points. “We’ve already flagged the attempted filing and forwarded it to the district attorney. Normally we send a warning first. Bringing a moving crew and threatening occupancy qualifies as escalation. If you enter without permission again, you’ll be trespassing. If you file anything else claiming ownership, it will be attached to a criminal complaint that has already been opened.”

The movers put their hands up like a show of good faith to gravity and backed toward their truck. Tyler stared at me as if a stranger had sold him an ocean.

“You’re seriously doing this to family?” he said.

“Family,” I repeated. “You showed up with a forged title and a moving crew. You tried to remove me from the last thing my grandparents asked me to carry. Don’t dress theft up in a sweater and call it Thanksgiving.”

My mother’s jaw clenched. “They were confused. We didn’t understand—”

“No,” I said, and I let the word sit between us like a chair no one wants to pull out. “You didn’t respect me enough to ask. You thought I’d be the same kid who skipped weekend plans to babysit Tyler’s latest disaster. I prepared because Grandpa taught me to listen for creaks. This house creaked before you got here. I heard it.”

Tyler broke eye contact first. He told the movers to leave and didn’t look back. My mother lingered like she wanted to try one last sentence. None came. She followed him to the car with her clipboard hanging in her hands.

When they were gone, the quiet was not victory. It was gravity. I stood on the porch where I’d sat with Grandpa and watched rain, and remembered all the times he’d told me not to judge people by the words they use when the lights are on, but by what they do when they think you’re not looking. I had looked. I had learned. And now I had acted.

Three days later, a letter arrived. Formal letterhead. A law firm with a name that sounded like a tavern. It was from an attorney hired by my mother. In clean paragraphs that hoped their calm would convince me they were reasonable, she claimed emotional distress and “familial obligation.” She argued that as a direct descendant she had a moral and legal right to a portion of the estate. Attached was a list of “reasonable reparations”: a $150,000 cash payment, joint ownership of the home, and a monthly allowance “until further notice.”

I read it six times. The first two passes, I tried to make it fit inside a narrative where my mother was overwhelmed, confused, misled. By the sixth, that narrative had slipped a disk. She wasn’t confused. She wasn’t overwhelmed. She was entitled. And she had found a lawyer to put that entitlement on letterhead.

I took the letter to the person I was paying to keep my head from exploding in a public place—my estate attorney, Sonia Cruz. She was the legal equivalent of a scalpel: soft-spoken, precise, deadly when necessary. I handed her the trust documents and the letter and the thin folder of screenshots I’d already started collecting like a person who had learned the hard way to always save receipts—Tyler’s “big things coming,” my mother’s “we handled it,” texts with timestamps and emojis that would look stupid in a courtroom and powerful in a pattern.

Within a day, Sonia sent a cease-and-desist to my mother’s lawyer and to Tyler. It spelled out in measured sentences what I wanted to shout: the trust was legally sound, their claims had no standing, and any further interference would be met not with patience but with paperwork and the kind of calls that make certain kinds of people think about their sentences before they speak. She also forwarded documentation of the attempted title filing to a fraud investigator at the DA’s office. Turns out the sketchy online registry Tyler had used was already on their radar. He hadn’t discovered a loophole. He had walked into an open case file and hung a name tag on his chest.

I didn’t tell my family that. I didn’t tell them anything. They had chosen their battleground: lies whispered to relatives, an attorney’s letter sent to my mailbox. I chose mine: facts written in black ink on white paper, delivered with certified mail receipts.

It should have ended there. If this were a movie, the scene would cut to Tyler doing community service in a bright vest and my mother sitting with her hands folded, staring at a wall and learning the lesson everyone hoped she would learn. But this wasn’t a movie. It was family.

The smear campaign arrived on little cat feet: a cousin’s text that read, “Just wanted to check in—you okay?” A voicemail from an aunt I hadn’t seen in years: “Heard some things. Hard for me to believe, but… call me.” Then a Facebook message from my cousin Megan, who I hadn’t seen since a wedding three summers ago.

Hey. Can we talk? Your mom’s saying some stuff. People are calling me. Figured you should know.

We met for coffee the next morning. Megan is not a person who likes the sound of her own voice; when she texts you, it’s because she has the kind of information that helps the story along. She showed me screenshots: family group chats where my mother had typed words like “manipulated” and “took advantage” and “changed the will when he was declining.” Voicemails that pitied Tyler’s “dreamer’s heart” and painted me as a cold accountant of other people’s suffering. She was calling everyone. She was calling within the hour of me refusing to pick up. She was building a narrative with speed and confidence. She had miscalculated one thing: her audience. I might be the quiet one, but I am not without people who have practiced listening.

“I don’t believe her,” Megan said. “Neither does Jaime. But she’s not going to stop.”

I went home and built a better machine.

Sonia helped me draft a factual declaration—the kind that has a table of contents and exhibits numbered like a careful teacher’s nap. It included the trust documents, the filing date, the notarized pages with the stamp that had jurisdiction and the ones with the stamp that did not. It included the cease-and-desists, the attempted title transfer with the fake notary that looked like a child had made a forgery kit on a printer, the county’s file number. It included a log of calls and texts and the attorney’s letter demanding “reparations” because nothing says familial love like a demand for $150,000. It included the “big things coming” socials because jurors don’t exist here, but the court of extended family does, and they speak Instagram as a second language.

I wrote a short message and attached the packet. I sent it to every relative I knew my mother had called. Twenty-seven contacts. I didn’t add commentary. I didn’t call names. I wrote, “Before you decide what you believe, here are the facts. After you read them, I won’t be discussing this again.”

My phone buzzed like a trapped hornet for a day and a half. Half of them apologized. A quarter doubled down, said documents could be faked too, and that made me laugh longer than it should have because if I were going to fake something, it would not be a fake notary stamp with a zip code that doesn’t exist. A handful said what I needed someone to say out loud: “I’m sorry we didn’t notice before. We assumed you were fine because you were quiet.” You can’t build back the years with words, but you can lay down a plank.

Once the family had been taught how to read, I turned my attention to the part of the story that could hurt Tyler where he most enjoyed being seen: work.

He’d landed a job at a boutique real estate firm whose website was better at photo filters than disclosure forms. Their “About” page bragged about transparency and ethical transfers with the confidence of people who have never been sued. It also had an anonymous ethics line.

I didn’t call it soaked in rage. I wrote a report like the boring man I have secretly become: exhibits labeled, timeline clear, risk assessment elevated. I branded it with the company’s own language about integrity and asked a polite question at the end: does attempting to steal a historic property using a forged title filed through a registry currently under criminal investigation align with your values?

Two days later, Tyler’s headshot vanished from their website. A week later, I got a text from a college contact who works in state licensing: “FYI: your brother’s license is on ice pending inquiry. Yikes.”

He called me eleven times that day. I let each one go to voice mail like you let a kettle boil dry because you forgot it on the stove. He posted a black square with white text: “Some people will destroy your life and pretend they’re the victim.” I didn’t answer. His audience had gotten smaller.

Then came the official letter from the county: attempted property fraud, submission of falsified documents to a government agency. Arraignment date set. No headlines, no parade. Just paper that weighs the same as other paper and words that take up space in the world in different ways now.

This was never the ending I wanted. I don’t know a brother who dreams about filling out forms that may keep his brother out of a career forever. I don’t know a son who wishes to be the person who teaches his mother that the word “no” can be a complete sentence even when you raised the person saying it. But wanting a different ending doesn’t make this one untrue.

The last piece arrived two months later, in a letter my attorney slid across her desk with one manicured finger. It was from my mother’s lawyer. “All claims withdrawn.” A single sentence requesting “no further contact.” The legal equivalent of a slammed door written in a font that doesn’t do drama.

Later that night, I walked barefoot along the hallway of the Victorian. The floorboards hummed their familiar notes under me; the house sighed the way old houses do when the temperature changes. I stopped in the den where the leather armchair still held the gentle indent of my grandfather’s spine and stood for a moment with the silence he’d liked so much.

“I kept it safe,” I said into that quiet, because I needed to say it out loud once to someone who would have cared. “Just like I promised.”

I went upstairs to the small bedroom with the window that faces the maple tree that outlived three roofs and opened one of the boxes I hadn’t let myself open yet. The top one had photographs in it—grandparents looking like movie stars in black and white, my mother with her hair piled high in a decade that tried to make itself immortal, Tyler grinning in a Christmas sweater he’d ripped a hole in on purpose to call it vintage. Me, sitting on the porch step next to a wrench, looking younger than I remember feeling even then. I put that picture on the mantle. Not because I needed to see my face every day, but because I needed to remember the man who sat there and changed.

The house was quiet. The paper was filed. The phone was off. The trust was real. I went to sleep in a room that belonged to me and to the people who raised me to be boring enough to save important things.

Part Two

After the fight is when you find out how much of you was made of fighting.

Most days after “all claims withdrawn” tasted like water—necessary, almost flavorless, sometimes sweet. Some days the anger arrived late, the way thunder parks itself on a horizon and doesn’t leave even when the rain stops. I accepted both days and learned to put my phone in a drawer when the latter kind showed up.

Once a week I drove across town to the house before dusk when the light makes the ivy look like a story you haven’t read yet and watered the potted herbs my grandmother kept on the stoop. I hired a crew to replace the cracked mortar on the east side and watched them like an old man because sometimes the only thing you can control is whether the job is done right. I learned phrases like “historic district variance” and filled out forms that ask the same question four different ways because that is the price you pay for living in a city that tries to keep its memory intact.

Work became a place that didn’t demand I leave pieces of myself in the parking lot. I caught myself making jokes in meetings. I said “I’m not available then” when people asked me to be, and didn’t follow it with three excuses that made me sound apologetic. My boss stopped prefacing my name with “reliable” like it was a compliment you pin on someone who can’t handle “brilliant” yet. I asked for something I wanted. I got it. It turned out competence looks like magic only to the person who finally allows themselves to call it theirs.

Sometimes, on Saturday mornings, I cooked for just me and ate at the small table in my kitchen without checking my phone to see if anyone needed saving. The first time I made pancakes that weren’t so dense you could use them as coasters, I flipped the extra onto a plate and took them home to the house my grandparents built. I sat on the stoop and ate one cold and laughed out loud at myself. If old houses hold echoes, that laugh sounded like a child learning not to take himself so seriously that he doesn’t enjoy his own breakfast.

People treated me differently because I treated myself differently. It is both cliché and true. The friend who only called when he needed a truck to move his couch stopped calling; the friend who called to ask if I wanted to see a movie I did not want to see kept calling to ask if I wanted to see other things and I started saying yes. My neighbor across the hall who used to borrow sugar like I had stock in a refinery started leaving tomatoes from her garden at my door. I left a note: You are the only one allowed to ask me for things without planning to give me nothing back. She laughed when she read it in the hall. We ate a tomato with salt over the sink and didn’t cry about anything.

Sometimes the old temptation arrived dressed in old clothes. A number I knew but had silenced would flash across my screen and my chest would tighten in a pattern that resembled loyalty and turned out to be habit. I kept letting those calls go to voicemail because sometimes love looks like not picking up.

Then, one day in late autumn, as the last of the maple leaves freckled the front lawn and made the sidewalk look like a mosaic, I opened my mailbox and found a plain envelope with no return address. It wasn’t legal. It wasn’t typed. It was from my mother. I knew because you can recognize a person’s handwriting after the age of five the way you can recognize their laugh at a crowded party.

Inside was a single sheet of paper with six sentences and not a single excuse. She wrote that she was renting an apartment near the bus line. She wrote that Tyler had taken a job he thought was beneath him and found out humility is an elevator. She wrote that she hadn’t spoken to me because she didn’t know how to speak to me without trying to make me smaller. She wrote that she was sorry for the stories she told and the ones she believed. She wrote that she wanted to be better, and if I ever wanted a grocery store conversation that didn’t end in tears, she was available on Thursdays after three. She wrote that my grandmother would have been proud of me, and it did not feel like a manipulation when she wrote it.

I didn’t write back. I didn’t crumple it up either. I put it in the drawer with the other letters—the cease-and-desists and the court numbers and the postcard from Uncle Ray that still made me grin like a child. Letting something live in a drawer is its own answer: I am not throwing you away, but I am not putting you on the fridge yet.

In late November, Uncle Ray invited me to a dinner that was not Thanksgiving. “Burgers,” he said, “and paper plates. No speeches.” I brought a salad because I’ve become that guy and refused to be ashamed. Jordan was there in a shirt that fit his shoulders. He walked over and did not try the hug that belongs to people who haven’t tried to steal houses. He looked me in the eye and said, “I got through the hearing. Probation. Fines. No prison.” He paused. “I don’t deserve it, but I’m grateful for it.”

“Good,” I said.

“I’m working four shifts a week,” he added. “Turns out you can be tired in a respectable way.”

“You always could,” I said, because sometimes generosity sounds like an insult and sometimes it sounds like what it is, and I didn’t want to mix them up.

We ate burgers like the sermon we weren’t giving. My mother arrived late and waved from the sidewalk like she was approaching a tenuous treaty. She didn’t try to sit next to me. She didn’t cry. She took a plate that was already made for her and said thank you. At some point, she tapped my shoulder on her way back from the kitchen and said, “I sold the china,” like the confession it was.

“Good,” I said. “You don’t need dishes to prove anything.”

“You kept the house,” she said, and it came out as a statement, but it asked a question.

“I kept the promise,” I said, and it was both.

A week before Christmas, I took the trust’s binder out of the safe deposit box and brought it home because there are times you need to see the thing that saved you. I sat at the old kitchen table that I’d once convinced myself was too big for a single person to sit at and I opened it up to the first page and read the dullest sentence that had ever protected anything: This trust is irrevocable.

I whispered thank you to the sentence and to the people whose names were written on the backs of photographs in another box in the pantry. I went upstairs and slept in a room with the window that faces the maple now bare.

On Christmas Day, I did not go to the Victorian. I went to the little apartment my neighbor made smell like cinnamon and I brought the salad and a loaf of bread I can bake now without making it sad. In the afternoon, I drove across town and left a paper bag with pancakes and a note on my mother’s stoop: Thursday after three. The grocery store near the bus line. I’ll be there if you are.

She was. We stood in front of canned tomatoes and talked about nothing important for ten minutes. She did not say “I didn’t realize.” I did not say “You should have.” She put a can in her basket. I put the same can in mine. We walked to the checkout without any declarations that required new syllables.

The day after, I drove back to the house with a snow shovel and cleared the sidewalk in a straight line that felt like ceremony. A kid from down the street walked by with a sled and asked me who I was. The kind of question that once would have made me say, “No one important,” because I was very good at smallness. I rested the shovel against my leg and said, “I’m the guy whose grandparents lived here.”

“Cool,” he said, and kept walking.

I am not a person who believes that suffering is required for meaning, but I do believe that endings require clear sentences. Here are mine:

I inherited my grandparents’ estate and quietly moved it into a structure that respected their work and my peace. My brother tried to steal it with a forged title and a moving truck. My mother tried to take it with a lawyer and a story. I met lies with information and theft with paperwork. I turned down the volume on guilt and apology long enough to hear the clean sound of no. I did not give them what they demanded. I gave them, eventually, the chance to live without thinking I was obligated to make it easier.

Tyler lost a job and found his capacity to wash dishes without shame. My mother lost a narrative and found the humility to let her hello be small. I lost the part of myself that made me useful to everyone but me. I kept the house. I kept the promise. I kept, finally, the version of myself that my grandparents would have recognized—the one who shows up, quietly, not to be used, but to honor what he loves.

END!

News

At My Brother’s Wedding, I Was Given a Folding Chair by the Kitchen… ch2

At My Brother’s Wedding, I Was Given a Folding Chair by the Kitchen… Part One My name is Adrien….

At My Nephew’s Birthday Party, I Said, ‘Can’t Wait For The Big Family… ch2

At My Nephew’s Birthday Party, I Said, “Can’t Wait For The Big Family…” Part One My name is Eli….

Found Out My Parents Left Everything To My Brother In Their Will, So I… ch2

Found Out My Parents Left Everything To My Brother In Their Will, So I… Part One My name is…

‘Sorry, This Table’s For Family Only,’ My Brother Smirked, Pointing Toward… ch2

‘Sorry, This Table’s For Family Only,’ My Brother Smirked, Pointing Toward… Part One My name’s Eli. I’m thirty-four. The…

When I Attended My Sister’s Wedding, My Seat Was in the Hallway. MIL Smirked.. ch2

When I Attended My Sister’s Wedding, My Seat Was in the Hallway. MIL Smirked.. Part One My name’s Alex,…

My Aunt Accidentally Sent Me A Video Of My Family Calling Me A ‘Pathetic Failure’.. ch2

My Aunt Accidentally Sent Me A Video Of My Family Calling Me A “Pathetic Failure”.. Part One My name…

End of content

No more pages to load