When did you FIRST realize that your parents were bad at parenting?

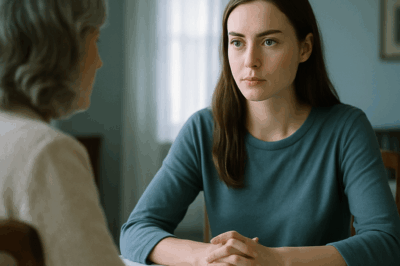

Part I — The Night the House Learned My Name

When I was twelve, my parents began disappearing on Friday afternoons with the same breezy line: “Marriage retreat—food in the fridge, forty dollars on the counter, doors locked, phone off unless it’s an emergency.” They kissed the air near my cheek, hauled two overnight bags to the trunk, and drove away while our neighbor Mr. Johnson pretended to prune his rosebushes and Mrs. Johnson peered through lace curtains that weren’t meant for peering.

At first, the weekends felt like a prize I had somehow won. No bedtime, pizza for breakfast, a video game console humming like a friend who never asked me to lower my voice. I called it freedom because I didn’t have a better word for loneliness yet. I memorized the clunk of the ice maker and the exact second the porch light clicked on. I learned how long microwave popcorn can take before the smell becomes a memory you can’t get out of curtains.

By the third weekend, the thrill thinned. The house began making the kind of noises you only hear when you’re the only one listening—pipes sighing, a window frame shifting, the dryer rumbling like a far train even when you know you never turned it on. I noticed how Mrs. Peterson next door started inventing reasons to drop by: a plate of extra cookies, a question about a book fair, a shy, lopsided smile as she asked if I needed help with homework she knew I’d already finished. She had a son in his twenties and a daughter in high school; she moved like a person who still remembered the tempo of kids’ lives.

On the fourth weekend, a storm rolled in on a Friday evening and took the power with it. The house exhaled and went black. I sat on the living room rug with a flashlight balanced on my shoulder like a nervous parrot and watched the rain peel down the windows in sheets. I told myself I would not cry. I told myself it was just weather. Then I told myself an old lie from childhood: that if I stayed very still, nothing could see me. Sometime after midnight, a soft knock tapped the doorframe, and Mrs. Peterson’s voice gently lifted into the dark.

“Where are your parents, honey?”

“They’re—um—running errands,” I said to a spot over her shoulder.

She looked past me into the house, then back at my face. “Want to come over until the lights come back?”

We crossed our small patch of wet lawn together. At her place we played Scrabble with too many blank tiles because her daughter had lost a few years back and everyone had pretended it was fine. We ate grilled cheese that tasted like the opposite of fear. We watched a movie none of us finished because falling asleep on a couch can feel like being chosen when you’re twelve.

By Sunday evening, I was back in my own dark living room, pizza box on the counter, TV off, pretending the weekend had been easy. When my parents walked in, my mother asked if I’d remembered to water the plant by the sink. My father asked if I’d done the math packet for Monday. “How was the retreat?” I asked, testing the word in my mouth the way people test a new language.

“Good for us,” my mother said, in a tone that suggested the sentence didn’t need a subject.

After that, Mrs. Peterson’s Friday text became a ritual. Power’s looking unstable tonight. Might want to come over just in case. We both knew the grid was fine. I packed a backpack anyway. Her house felt like another weather system—warm front, low pressure, chance of laughter. Her son showed me a trick for beating the chess computer on his battered laptop. Her daughter explained how to make scrambled eggs that didn’t break. On Saturday nights we went to the grocery store together because errands in company are a kind of ceremony. I told myself it was temporary. Temporary can stretch.

One Friday, my parents didn’t leave. My father had a lingering cough; a doctor he liked had told him to rest. The retreat was canceled, the house stayed full of adult footsteps for the first time in weeks, and I felt… disappointed. I stared at the feeling like a strange insect that had landed on my sleeve. That’s when Mrs. Peterson texted the usual line about the power. I told her my parents were home. She replied: Good. I was worried about you spending another weekend alone.

Another weekend alone. She knew. Of course she knew. The world always knows more than you think it does about the things you’re trying to hide.

After dinner, a firm knock took aim at our door. My parents were murmuring in the living room about a work matter that always ended with “you don’t need to worry about that” when I walked down the hall, my sneakers soft on the runner. My father opened the door wearing the face he uses for ushers at church and new neighbors with baked goods.

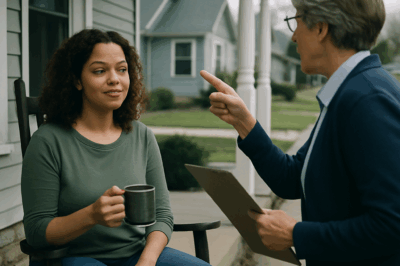

“Good evening, Mr. and Mrs. Miller,” Mrs. Peterson said. She wasn’t alone. A tall man with a vest that said Child Protective Services stood beside her. He had the posture of someone who lets other people decide whether a conversation needs to be loud.

“Is there some emergency in the neighborhood?” my father asked, tone pleasant, volume turned exactly to reasonable.

“It’s about your son,” the man said, glancing past my father toward the hallway where I stood, the old floorboard under my left foot betraying me with a creak.

My mother stepped forward, chin angled. “This is a misunderstanding. We are excellent parents. He is safe at home. Always.”

“We’ve received reports of neglect,” the man said, steady. “Of a minor being left alone for entire days, including during storms and power outages. The neighbor reports having taken him in more than once.” He did not look at Mrs. Peterson when he said neighbor. He didn’t need to.

My father’s posture shifted from chapel to courtroom. “We go on religious retreats. That’s not a crime. We leave food, money. He’s twelve, not a baby.”

“Leaving a minor alone for days is illegal,” the man said. “We need to speak to him now.”

“I’m sleeping,” my mother blurted.

“Son,” the man said, ignoring her, “can you come here for a moment?”

I wanted to bolt to my room and hold the door closed with both hands like I did when I was small and thought latches were promises. Instead I walked toward the open door. Mrs. Peterson’s eyes met mine, warm and steady as a hand on a fevered forehead. “Everything will be okay,” she whispered, a sentence that felt like a life raft even if I didn’t yet believe in boats.

“Were your parents home the last few weekends?” the man asked, squatting so we were parallel.

My parents’ faces floated in the corner of my eye, their expressions trying not to be expressions.

“No,” I said, and something opened in my chest that I’d been holding closed. “They left Friday and came back Sunday night.”

“You’re exaggerating,” my mother said.

“And you were alone? No adult in the home?” he asked.

“Just me and the TV,” I said. “Sometimes the power went out. Mrs. Peterson helped me.”

He nodded, wrote. He asked if we could talk at the gate. Outside, under the porch light, he asked me for dates, times, details I hadn’t realized I’d kept in a neat file inside my skull. He gave me a card. “If this happens again, call me,” he said. “This isn’t your fault.”

When the door closed behind him and Mrs. Peterson, my mother turned, color blooming in her cheeks. “You told them everything. Do you want to destroy our family?” she hissed. The word family sounded like a shield she was too tired to carry properly.

My father didn’t say anything. He stared at a spot on the wall as if somebody had told him there would be a painting there if he was patient. It was the first night I realized they were scared. Not of losing me. Of being seen.

Part II — Cards, Codes, and the House with the Banner

The next morning my mother marched to Mrs. Peterson’s front steps and rang until the bell sounded like a distress call. I watched from my window as Mrs. Peterson opened the door a crack and then wider when she saw it was my mother and no one else. There was no pretense.

“You’ve crossed a line,” my mother declared. “This is slander. If my son is taken from me, you’ll pay.”

“I am not afraid of you,” Mrs. Peterson said, very calmly. “Report again? I will. He deserves parents who are present.”

The door closed with the kind of finality you don’t get from anything that’s only wood.

On Monday, a black sedan idled across the street when I got off the bus. A man with dark glasses sat inside pretending not to be watching. Every afternoon that week the car appeared when I did, waited a while, then left. It should have been ominous. It felt like an escort.

Inside our house, my parents changed their theater. Elaborate dinners appeared: roast chicken, three sides, a bowl of fruit so glossy it might have been wax. They left the front door ajar so anyone walking a dog would see us being normal. My father took calls from his office with the volume low. My mother walked with her heels landing softer than usual. Life took place at an inside voice.

At school, the story spread like a rumor that had finally found the truth to fit its size. One of the Johnson kids told a classmate who told everybody: the boy at eighteen gets left alone. Some kids called me the neighborhood orphan. Some kids stared like I was a sad movie. The principal called me into her office and asked if I wanted the school counselor to follow my case. I said I wanted to study in peace. She said that was also an option.

Friday arrived and my parents tried a new script. “Quick trip,” my mother said, too bright. “Back by dinner.” She didn’t mention the retreat. When they left, a patrol car rolled down the block like a reminder. I locked the door behind me and did not feel like a prisoner. I felt like someone responsible.

Mrs. Peterson opened her door before I could knock. “Lasagna,” she announced, as if that single word were adequate emotional language for boys twelve to eighty. It almost was. Her living room always smelled like something forgiving. We ate at the table with mismatched chairs that had been painted at different times in different colors because life had not stayed steady enough to match anything on purpose. Her daughter, Aubrey, tried to teach me chess again. Her son, Marcus, asked if I wanted to learn how to wire a lamp. I learned both, badly.

On Sunday evening, a social worker met my parents at our front steps when they returned. I watched from Mrs. Peterson’s window as my mother straightened her blouse and my father put the good smile on. The conversation lasted an hour. When the door closed behind the social worker’s careful shoes, my mother hurled a glass at the wall. It shattered into a map of something I didn’t want to learn to read. “What did you want?” she screamed, not a question. “For us to stay here every weekend because you’re afraid of the dark? We’re saving our marriage.”

The next week, envelopes appeared in Mrs. Peterson’s mailbox without stamps. Notes typed in a font that wanted to look like a warning and only managed to look like it had given up on handwriting. It’s dangerous to meddle. Good neighbors mind their own business. Everyone knew the source. Mrs. Peterson pinned one note to a corkboard in her kitchen under a grocery list. She made tea.

On Thursday, a banner appeared on the Johnsons’ porch, hand-painted and crooked. CHILDREN DESERVE PRESENT PARENTS. PROTECT YOUR CHILDREN. I stared at it like you stare at a sky you thought was empty and find a constellation you should have known was there the whole time. My parents saw it too. My mother called it persecution. My father called it a conspiracy. The neighborhood called it a message.

On Friday, the social worker returned with a folder and a decision. “While the investigation proceeds,” she said, “Lucas cannot be left alone. If you go out, he goes too, or a legal guardian stays in the home.”

My mother laughed once, and the laugh cut itself. “This is absurd.”

I said nothing. When she slapped me—open palm, sharp, more punctuation than pain—in front of the social worker, the social worker’s pen paused once and then moved faster. The report would read: physical discipline administered in the presence of CPS personnel. It would be both accurate and not large enough to hold the whole moment.

Mrs. Peterson walked me out onto her porch that afternoon and pressed a laminated card into my hand. It fit my palm like a strange credit card. “If anything happens,” she said, “you call this number. Tell them ‘Lucas, case number 2073.’ You don’t have to wait for the whole world to be ready to help you.”

I tucked the card into the lining of my backpack, beneath the tear I’d once made with a pencil. Some things you keep where you can grab them in the dark.

And then, because people who are losing control rarely choose to lose it gently, my parents changed strategies. They stopped leaving me alone.

They started locking me in.

It began with “We’ll be right back, market run,” and a click I recognized as the sound of a key turning where it shouldn’t. They took their phones. Then they took mine, when they noticed Mrs. Peterson’s name lighting it up.

“You’ve made us look like monsters,” my mother said, handing me my backpack but not my freedom. “You’ll learn.”

Friday evening they left at sunset. The house relaxed into shadows that remembered my name and didn’t answer when I asked them to say it back. Every window had been latched and keyed. I sat on the floor with my back to the bed. I counted my breaths. Then I reached into my backpack, found the card by feel, and dialed.

“This is Child Protective Services,” a voice said, neither hurried nor bored.

“It’s Lucas,” I whispered, like my walls could tattle. “Case 2073. They locked me in. They took the phone. They took everything.”

“Are you hurt?” the voice asked, suddenly closer. “Are you safe where you are?”

“I’m alone,” I said, and it turned out that was both an answer and a request.

“We’re coming,” she said. “Stay by the door.”

Less than twenty minutes later, red strobes painted the living room ceiling. Two cars. One CPS, one police. The social worker I knew came in first, a folder in her hand and eyes like a person who cannot be lied to in the way that matters. A cop popped the front latch with the practiced efficiency of a man who has gotten very good at removing excuses.

“You okay?” she asked, crouching to meet me where I was on the floor.

“I’m okay,” I said, and in saying it I realized I was about to be.

They took me across the lawn to Mrs. Peterson’s house and told me to wait there while they called my parents. Through her curtain, I watched my mother and father arrive, faces pale like bad news. They walked toward our house and were met at the gate by two officers and a legal sentence spoken quietly. Temporary suspension of custody. Emergency placement. Words can be doors.

That night, Mrs. Peterson tucked a blanket around my knees on her couch and handed me a mug of hot chocolate so sweet my teeth almost ached. “You’ll never sleep alone in fear again,” she said, and the sentence fell into my bones and stayed.

Part III — What People Mean When They Say “Home”

The first week under emergency guardianship felt like waking up inside a dream and realizing the part about falling had been rehearsals for flying. I stayed with Mrs. Peterson while the paperwork moved along a track it knew better than I did. The school counselor met me in a quiet office and asked questions that were both careful and necessary. “Do you feel safe where you’re sleeping?” Yes. “Do you want to speak to someone weekly?” Maybe. “Do you need a new spiral notebook, this one has kittens on it?” Absolutely not. We compromised on solid blue.

Mrs. Peterson’s house taught me what people mean when they say home without thinking. Morning smelled like coffee and toast. Evenings sounded like whistling kettles and the news turned down low. There were photos on the walls that didn’t match their frames, kids growing up and out of those wooden rectangles in increments. I washed dishes not because anyone asked but because belonging makes its own chores.

One afternoon she sat me down in the living room and smoothed the edge of her skirt like a person steadying a boat. “I spoke to the social worker,” she said, eyes gentle but bright. “I’m going to file for guardianship. Not because I think I can fix the past. Because I want to give you a future that isn’t waiting for someone else’s plans.”

I didn’t cry. I collapsed into her lap and let my body shake the way a dog shakes after finally making it to shore. I didn’t say thank you. Some gratitude doesn’t come out in words without becoming smaller than the thing itself.

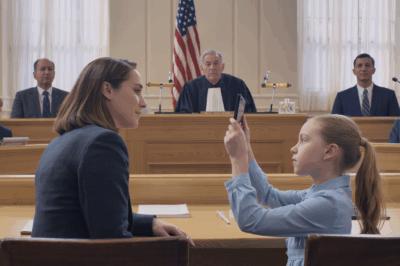

The hearing that made it real happened in a room with carpet that swallowed footsteps and a judge who looked like she still remembered what it felt like to be a rookie. My parents didn’t show. Their lawyer did, in a tie that looked tired. The judge read the reports, the call logs, the notes from the door, the photograph the officer had taken of the lock with the key on the wrong side. She spoke in a voice that knew the difference between mercy and permission. “Guardianship granted,” she said. The gavel touched wood like a light switch.

My parents’ next move was to be present in all the wrong ways. They parked across from my school for an hour on a Tuesday, my father staring through the windshield as if police cars were mythological. They mailed letters that read like scripts for a play about dignity written by someone who had never seen it. They slipped notes through Mrs. Peterson’s gate: He’s been poisoned against us. You destroyed our family. The social worker filed the paperwork, the judge signed the order, and a new sentence joined the stack: restraining order, five hundred meters. My parents moved to another city. Grief didn’t arrive with the news. Relief did.

I started sleeping through the night. When I woke from the occasional bad dream, Mrs. Peterson made tea and sat on the couch with me until the shapes in the corners of the room turned back into furniture. She never asked me to explain the nightmare. She knew explanations have to hatch on their own time.

At school I learned to lift my hand again without sweating. My grades moved from fine to good to excellent the way weather moves across a map when no one is interfering. I brought home a report card with all blue marks and Mrs. Peterson taped it above the coffee maker where no one could miss it. For my next birthday she baked a cake with my name on it in icing that refused to form neat letters. I ate the first crooked slice standing up.

It turned out you can learn to breathe in a house. I learned to breathe in hers. I learned the feel of a key that belongs to you and what it does to your spine. I learned to pack lunches the night before and to coil a hose on the side of a house neatly because you should leave order behind where you can. I learned that love is a long verb, not a loud noun.

Years turned. I changed schools once, then again for high school. I learned to ride the bus with music in my ears and not get off at the wrong stop even when the day felt too big. I fell in with a quiet crowd who liked movies where nothing exploded and board games complicated enough to require little bowls for the pieces. I got my first job bagging groceries and learned that being useful can fix most kinds of sadness in an afternoon.

Mrs. Peterson came to my high school graduation in a dress that made her look like the version of herself in the photograph near the hallway, holding baby Aubrey. She cried throughout the principal’s speech. When I crossed the stage, she cheered like I had invented walking.

I wrote one line for the program because they gave us a box and told us to fill it with gratitude. I wrote: “To the woman who saved me from being invisible—my mother.” The registrar asked if I wanted to change mother to guardian for accuracy. I shook my head.

College was a bus ride away. I found an apartment with a kitchen too small and a window that made up for it. I took a part-time job on campus and studied not because anyone promised me a better life if I did but because the work itself made a human shape around me. Sundays I took the bus back to Mrs. Peterson’s house for lunch. She had a new way of walking, slower, deliberate, but her hands still moved through a room like they knew where everything belonged. We developed the kind of arguments you can have with someone you know won’t leave if you are wrong. We fought about whether cilantro tastes like soap. We fought about whether it matters if a towel is folded in halves or thirds. We fought, kindly, about whether I was eating enough vegetables. She always won. That was the point.

Then, because life enjoys testing what you claim to know, the public defender’s office called. My biological parents had inquired whether a supervised visit would be possible. They had moved again. They said they wanted “closure.” The word landed on my kitchen table like a glass of water you didn’t remember asking for.

I brought the question to Mrs. Peterson over roast chicken and perfectly boiled potatoes. She held her tea in both hands. “I don’t like them,” she said, with her usual gentle honesty. “And I don’t trust them. But I don’t believe in keeping a door closed if you need to open it to see what’s still behind it. Only you can decide.”

I agreed to a meeting in a small, neutral room with a table and a box of tissues placed where everyone could see them—even the people who would not use them. My father had more gray. My mother’s hair had given up pretending to be what it used to be. We sat. They did not apologize. They said they’d tried their best. They hoped I was well. I said I was.

We met again twice more that year. The conversations went like that—polite, distant, factual. I learned the name of the street where they now live. I learned the name of the church where they listen more than they speak. I learned they had not learned the one lesson I needed them to, about presence and children and weather. I walked away with a quiet I could put down and pick up again without cutting my hands.

One Sunday afterward, I found Mrs. Peterson on the porch watering plants in a blue pot she called “the stubborn one.” I sat beside her. She waited for me to start.

“Was it worth it?” she asked finally.

“Yes,” I said. “Now I know who they are. And I know who you are.”

Part IV — Learning the Language of Enough

Time did what it does: softened some edges, sharpened others. I moved from part-time to full-time at work and discovered the modest satisfaction of answering emails the day they arrive. I discovered I cared about calendars more than I thought I would. I mowed Mrs. Peterson’s lawn on Saturdays until she told me I was making the grass arrogant. We compromised on every other week.

The house next door, my old address, sold. A young couple with a toddler moved in. They painted the porch rail yellow. They argued, loudly, about where the bookshelf should go, then kissed in the front yard under the pretense of checking the mailbox. I watched them for a little while and made a choice: to not resent anyone for getting a thing I didn’t get when I wanted it. This is a choice you make daily, like flossing. Some days you do it; some days you promise you will tomorrow.

The Johnsons moved, then moved back two streets over years later, claiming the sun never fell as well in their new kitchen. They came by on Sunday afternoons with pie and gossip that made sense only if you’d lived on the block long enough to know everyone’s maiden names. We referred to the banner they’d once hung only in metaphor. They didn’t put up banners anymore. They didn’t need to. Everyone had gotten the message.

Mrs. Peterson began walking with a cane. She didn’t like it. The cane had opinions. It hit thresholds like punctuation she hadn’t intended. On a Tuesday evening she slipped in the kitchen. I found her sitting on the floor, annoyed, more hurt pride than hip. We laughed because the world insists we do at exactly the wrong times. I helped her up and sat her on a chair with a cushion and an old, reliable joke. “You’re grounded,” I said. “From gravity.”

Her daughter Aubrey visited more often. Marcus came on weekends and fixed a hinge I had been pretending not to notice. I learned how to make the roast the way she did, and I learned that a recipe is a map only if you already know the town. On one quiet afternoon I found a shoebox in her closet labeled in neat block letters: Lucas. Inside were the laminated card, the case number, the first report card with all blue marks, the newspaper clipping about my high school honor roll, a program from graduation. She had kept everything I thought I had to carry alone.

The public defender’s office called again—my parents had inquired about one last visit. The phrase last visit sat in my throat like a pill I didn’t want to swallow with water. We met in the same room as before, but it felt smaller, as if time had crowded the corners. My parents’ faces had softened into the kind of tired we all arrive at, if we’re lucky, after long enough on earth. My father asked what I did with my weekends. I told him about lawn mowing, grocery shopping, a movie I’d liked. My mother asked if I was happy. I said yes. It was true enough.

Afterward I walked the long way home and stopped at the fence line between their former house and Mrs. Peterson’s. The grass did that thing it does in late summer where it believes it could be gold if only you didn’t look at it. I stood a while, then went inside. Mrs. Peterson was watering plants.

“So?” she asked.

“It was worth it,” I said. “To know. To be sure.”

“That’s all any of us get,” she said. “The chance to be sure of what we can be sure of.”

One winter morning she called my name from the bedroom and the voice had a shape I hadn’t heard before. I found her sitting on the edge of the bed with her cane on the floor, her breath tucked high in her chest. We went to the clinic. We went to the hospital. We came home with new instructions. We did the tedious work of obeying them. She whispered an apology the first time I helped her put on socks. “Don’t,” I told her, because sometimes gentleness is a command. “You taught me everything that matters. Let me do this one small, boring, important thing.”

We made new rituals. I labeled pill bottles in block letters big enough for both of us to read. I moved rugs. I learned which doctors deserved their diplomas and which were simply renting the titles. I learned how much salt her soup liked. I learned that a person can remain stubborn and grateful in the same minute, and that minute can last an hour if you sit with it.

On a spring afternoon, we sat on the porch while kids two houses down learned to ride bikes, all elbows and shrieks and bravery. Mrs. Peterson leaned her head back and closed her eyes against the sun. “You know the question,” she said, a smile catching one side of her mouth. “When did you first realize your parents were bad at parenting?”

I laughed; it was an old joke by now. “When the lights went out,” I said. “And the person who came to the door didn’t live in my house.”

“And now?”

“Now I know,” I said. “Parent is something you do. Not something you are.”

Part V — The Clear Ending You Asked For

If you’re waiting for a courtroom twist or a last-minute confession, I can’t give you one. This is not that story. This is the story of a boy who learned the names of his fear and his rescue at the same time. It’s the story of a neighbor who declined to look away and instead looked straight at a problem until it blinked. It’s the story of a house that was too quiet learning to share its noise, and a different house that had just enough noise to teach a kid what normal sounds like.

My biological parents moved again. I don’t know where. We exchange letters some years with weather reports and the names of new churches. We did not install a new relationship. We did something else: we installed a boundary. No contact without notice. No questions without answers. No pretending. We keep it. That is love, too, in a certain light—respect as a distance that protects everyone from the worst versions of themselves.

Mrs. Peterson’s cane got a friend, then a walker. On a Monday she laughed at the television, then nodded mid-afternoon, then slept. The nurse said the phrase “complications.” I said the phrase “thank you” to everyone in scrubs, all day, because gratitude is a habit you learn from people who deserve it. We buried her with a program that listed the names of her children, including mine, and the dates that never tell the whole story, and a hymn that made the room feel like the ceiling had decided to rise.

I cleaned her house the way you clean a beloved book—slowly, with a soft cloth, pausing to let dust be dust and not the past. I found lists tucked into cookbooks, notes to herself written in margins no one else would ever see: Remind Lucas to take an umbrella. Put out towels for him Sunday. Ask him about the class. This is how love hides—folded into sentences too small for posters.

Her will was simple. She left the house to Aubrey and Marcus and a note that said Please water the stubborn plant. She left me her old record player and a stack of albums we’d played on evenings when weather turned itself up and we decided to listen. She left me a letter I won’t quote because some words are meant for exactly two eyes at a time. In mine she wrote the truest thing I know: You saved me right back.

I go by the old house sometimes after work and sit on the porch with the record player humming inside. I watch the neighborhood do its slow ballet—dog walkers stopping to let dogs negotiate the news, delivery drivers jogging back to vans, kids practicing free throws that decide nothing and everything. The Johnsons wave from their new porch. The young couple with the yellow rail hangs paper bats at Halloween and paper hearts in February and paper stars in June for no reason other than joy requires props sometimes.

People still ask, every now and then, the question that launched this story: When did you first realize your parents were bad at parenting? I answer the same way every time. I tell them about the night the power went out and the storm made the house small and a soft knock became a rope. I tell them about a laminated card and a case number and a woman who handed me a future like a folded map. I tell them about a judge who knew how to make a gavel sound like a promise and a neighbor who turned “neighbor” into a job title. I tell them love can be a verb you learn at twelve and practice until you’re old, with volunteers and notes and grocery lists and doorways left open at just the right time.

You asked for a clear ending. Here it is.

I grew up. I stayed. I left, a little, then came back on Sundays. I learned the recipe and the rules and the exceptions. I forgave, in a way that doesn’t require Christmas or hugs or rewriting history. I did not forget. I didn’t have to. The forgetting belongs to people who need to make their stories fit inside smaller rooms.

The first time I brought someone I loved to the block, we walked slowly past both houses. “This is where I learned how to be alone,” I said, nodding at the old address. “And this,” I said, nodding at Mrs. Peterson’s porch, “is where I learned I didn’t have to be.” We climbed the steps; the stubborn plant was blooming. I don’t know what it’s called. I only know it keeps trying, and someone kept watering it, and the combination made a miracle out of something ordinary.

When I go home now—to my own small place with a window that believes in light—I sometimes hear a kettle whistle in my head. I picture a laminated card in a shoebox. I picture a banner on a porch that didn’t fix anything by itself and fixed everything by starting. I picture a boy sitting on a floor with his back to a bed, holding a phone and a breath at the same time.

And I answer the question inside myself again so I never forget. The first time I knew was the night my parents left and a stranger came to my rescue because she refused to stay a stranger. It wasn’t thunder or police lights or a judge’s voice that changed my life. It was a knock. It was a neighbor saying my name like it belonged where she could hear it. It was a woman with a record player and a cane and a way of turning the lights on that made the dark behave.

That’s the ending. No banner drops. No trumpet calls. Just a porch with two chairs. Just a kettle that knows when to sing. Just a life that holds because someone who didn’t have to chose to hold it. And a child—me—who finally understood that the question isn’t when you first realized your parents were bad at parenting.

It’s when you first realized somebody else was good at it.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes… Part I: The Answer…

HOA Karen Tried to Fine Me for Drinking Coffee in My Front Yard!

HOA Karen Tried to Fine Me for Drinking Coffee in My Front Yard! Part I: The Violation The morning…

My BROTHER got me KICKED out of the house so he could use my room as a game room…

My BROTHER got me KICKED out of the house so he could use my room as a game room… …

MY PARENTS SUED TO EVICT ME SO MY SISTER COULD OWN HER “FIRST HOME.” IN COURT, MY 7-YEAR-OLD ASKED

My parents sued to evict me so my sister could own her “First home.” In court, my 7-year-old asked the…

At My Birthday Lunch, My Daughter Whispered “While I Distract Him…” But She Forgot Who Built It.

At My Birthday Lunch, My Daughter Whispered “While I Distract Him…” But She Forgot Who Built It. Part I:…

My Sister Fired Me from Our Family Foundation Then Smirked as Our Parents Called It “Fair”…

My Sister Fired Me from Our Family Foundation Then Smirked as Our Parents Called It “Fair”… Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load