“What’s that patch even for” then the colonel said, “Only five officers have earned that in 20 years”

Part I — Arrival

Morning sunlight knifed through the tall windows of Fort Bragg’s administrative building and threw hard squares across the polished linoleum like a drill sergeant’s idea of geometry. The air conditioning hummed against the July heat—the kind that pressed your skin and told you without words to respect North Carolina.

I adjusted the webbing of my document bag and checked the time. Early. I prefer early, the quiet ten minutes before a room decides what kind of day it’s going to have. The strap lay just clear of the burgundy-and-gold patch on my right sleeve, faded by a lifetime of wear that was both shorter and longer than it sounds. A quarter-sized insignia: crossed swords, a shield, a single star above. Most days it felt weightless. Somedays it felt like everyone’s eyes.

“You must be Captain Reeves.”

I turned. The lieutenant had a brand-new stiffness to him, the way fabric looks before sweat and time teach it how to be useful. His name tape said HARRIS. His smile widened a little too fast.

“That’s right, Lieutenant.”

“Yes, ma’am. I’m supposed to show you to your desk and brief you on the staff structure.” His gaze flicked to the patch like a moth toward an unfamiliar flame. He blinked, recovered. “Welcome to Joint Operations Planning Division.”

We moved through corridors lined with decades: framed photographs of commanders who learned their lessons the hardest way, group shots of units that had swallowed dust in different decades and different deserts. The hallway smelled like coffee and copier warm-up and the particular disinfectant the Army buys by the lake.

“Most of the planning staff are majors and lieutenant colonels,” Harris said. “You’ll be working directly under Colonel Daniels, though he’s currently overseas for a week. In the meantime, Major Thornton is interim division chief.”

I nodded, mentally mapping exits and fire extinguishers and the precise sound each ID card reader made when it liked you. Old habits are just habits you haven’t apologized for.

Open office space. About twenty officers, each with a desk that spoke the shorthand of its occupant: maps rolled tight, highlighters by color, mugs with unit crests, mugs with jokes. Keyboard clicks layered into the murmuring rhythm of work. The air had the tension of competence—people who like being good at their jobs and like it more when you notice.

“Your desk is in the back corner,” Harris said. “Coffee station is by the south wall. Briefing rooms are down that hallway. Morning staff meeting in conference room B at 0800.”

As I set my bag down, two majors at the next workstation exchanged glances. The broad-shouldered one with gray at his temples let his eyes rest on the patch and smirked like he’d solved a riddle. The woman beside him, lean and sharp-eyed, straightened as if I’d arrived late to a test.

“Lieutenant Harris,” the gray-templed major called, voice pitched to carry. “What’s the new captain’s background?”

Harris, to his credit, glanced at me first. “Major Thornton, this is Captain Reeves. She’s transferring from…” He checked his tablet. “…previous assignment classified.”

Thornton stood and crossed the aisle with the posture of a man who’d practiced entrance. “Welcome, Captain. David Thornton. I’m running things until the colonel gets back.” He extended a hand. His eyes did that quick slide: name tape, badge, patch.

“Thank you, sir,” I said, grip firm. The Army shakes hands the way it drives convoys—short, direct, no weaving.

“What unit is that from?” asked the woman, reading my name tape—PRESTON—off my shoulder like a diagnosis.

“It’s a specialty insignia, ma’am.”

“For what specialty?” A little too much edge to be curiosity.

“That information is restricted, ma’am.”

The room took a breath. Heads pretended to go back to work.

Thornton’s smile went cool. “We value transparency in this division, Captain. Classified backgrounds and mysterious patches don’t mean much when actual planning begins. You’ll find that out soon enough.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, the words as neutral as Norway.

They drifted back to their desks. Harris lingered, a good kid caught between his rank and his sense. “Ma’am, I should mention… the major is very proud of his deployments. Three tours Iraq, two Afghanistan. He’s skeptical of officers from training or admin.”

“I understand,” I said. I didn’t add that skepticism is just fear in nicer shoes.

0800 came fast and loud. The conference room had that institutional hum—projector, HVAC, fluorescent lights resigned to service. I took a seat near the back. Thornton positioned himself at the head of the table, owning the center of gravity like a man who’d memorized gravity’s phone number.

“Before we begin,” he said, “our newest member. Captain Reeves has joined us from a classified assignment she can’t tell us about.” His smile wanted to be a joke. His eyes wanted to put me somewhere. “I’m sure her mysterious background will be useful for planning logistic support operations.”

A few soft laughs. Fine. The Army underestimates quietly and overestimates out loud.

The briefing was routine. Training exercises. Equipment requisitions. Coordination with allies who like us until we ask them to do something with us. I took notes, contributed where the gaps were obvious. Protocols have a music to them. I’ve always been good at harmony.

At the break, a captain with kind eyes and a pilot’s slightly-wrecked sleep pattern approached while I poured coffee that smelled like ambition. CHEN, his tape read.

“Don’t take Thornton personally,” he said. “He’s good. Also convinced that if you haven’t been shot at, you haven’t served.”

“I’ve noticed that bias,” I said, stirring. “The patch though,” he added, tipping his chin at my sleeve. “Twelve years in, never seen it. Is it really that classified?”

“Yes, Captain. It is.”

“Fair enough.” His shrug was respectful. “They’ll speculate. Preston already told someone it’s for a special diversity program.”

“People can speculate,” I said, sipping. “It doesn’t change what it represents.”

By Friday, the rumors had matured like bad wine. Foreign exchange program. Ceremonial trinket. Surplus store special. I heard them the way you hear your own name in a crowded room—not because you want to, but because you’ve learned to.

At 1600, Harris hustled to my desk. “Ma’am, I hate to add to your workload, but Major Thornton wants you to prepare a briefing on alternative supply routes for the exercise. Monday morning.”

“That’s a significant analysis for a weekend,” I said. Out the window, the heat turned the parade field to a mirage.

“I think he’s testing you,” Harris said. Apologetic, like it was his idea.

“I’m sure he is.” I slid a notepad toward me. “Tell the major I’ll have it ready.”

The office is different on weekends—echoey, honest. I spread maps like cards, pulled data, built models, called motor pools while young sergeants said “ma’am” with suspicion until they realized I made their lives easier instead of harder. The patch on my draped jacket caught light and memory. I worked until the building settled around me and started again when it woke.

Monday, 0745. The room had its performative skepticism. Thornton already at the head, Preston sharpening something invisible.

“Ready to dazzle us?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

I started on time. Terrain. Vulnerabilities on Highway 24—bridge load capacities, choke points, weather, accident patterns, what happens when a convoy becomes a parking lot and the enemy knows patience. I included driver rest cycles because human beings do the driving, not algorithms. Fuel consumption tied to real maintenance records. I switched slides. “Three of the assigned trucks have recurring transmission issues. They drop highway speed capability to…”

“How did you access maintenance records?” Preston snapped.

“I called the motor pool, ma’am. Asked.” I offered her a half-smile. “Due diligence.”

Her eyes admitted nothing. Her fingers tapped the table like Morse code for annoyance.

I presented three alternate routes, risks and mitigations, scout vehicles, comms redundancies that wouldn’t collapse when you needed them. Chen leaned forward, tracking my data like a friend following a story.

“You do all this over the weekend?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

Thornton leaned back, arms crossed, skepticism with triceps. “These calculations are conservative. Convoys move faster than this.”

“With respect, sir, not when following the security protocols for this exercise, accounting for driver rest, and factoring in mechanical failure rates,” I said. “My estimates are based on actual fleet capability, not optimistic planning factors.”

“What real-world experience do you have implementing supply operations under field conditions?” he asked, voice even, aiming for mentor but hitting mallet.

I met his eyes. “Extensive field experience, sir. I cannot discuss specifics.”

“Of course not,” he said, acidic. He gestured at the patch. “Just like that mysterious participation trophy.”

The room flinched. Even Preston’s eyebrows moved.

“My record speaks for itself to those with appropriate clearance,” I said calmly. “For everyone else, I demonstrate competence through my work.”

“And what makes you think a route analysis demonstrates competence?” he pressed. “Any fresh lieutenant with a computer—”

“Would not,” I said, “have included pages fourteen through seventeen.” He scrolled. “Threat assessment, interdiction tactics observed in similar terrain, countermeasures, response protocols.”

“Where did this tactical intelligence come from?” he asked, the question a shape he didn’t want to hold.

“Classified sources, cross-referenced with current threat reports and history.”

“Captain,” Preston said, less sharp, “are you suggesting you have intelligence access beyond—”

“I’m not suggesting anything, ma’am. I’m doing my job with the information I have.”

Harris raised a hand, earnest cutting the tension. “On route three, you mark enhanced security at these points. What makes them more vulnerable?”

“Population density increases, previous incidents in similar environments,” I said. “Extra scouts, redundant comms. Patterns matter whether it’s Helmand or I-95.”

Preston’s eyes flicked. She knew enough geography to hear ghosts.

Thornton stood. “This is ridiculous. We’re supposed to accept your recommendations based on data we can’t see? In my experience, people who hide behind classification are covering up a lack of credentials.”

I didn’t stand. I let the room notice that. “I respect your experience, Major. I’m not asking for blind trust. Every assertion is backed by doctrine and data anyone here can review. The rest comes down to whether we respect each other’s lanes long enough to get the mission done.”

He pointed at the patch. “Tell me, Captain, what combat experience does someone with a participation trophy patch actually have?”

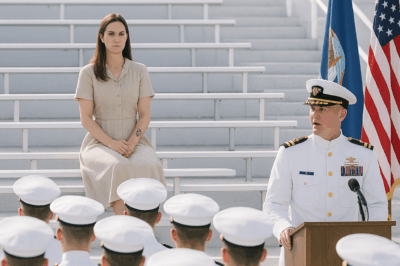

The door opened. All the air left with the colonel’s entrance and came back two seconds later when our spines remembered how to breathe. Silver hair. Weathered face. Ribbons that aren’t for show. “At ease,” he said, gravel calm. “Thought I’d be in Germany until Wednesday. I see you started the party without me. What’d I miss?”

“Sir, welcome back,” Thornton said quickly. “We were finishing a briefing by Captain—”

The colonel’s eyes landed on my sleeve and everything about him rearranged. He stopped, came to attention, and rendered a formal salute.

The room froze a second time in five minutes. I returned the salute. You never forget how.

“Captain,” he said, voice lower. “Honor to have you in my division.”

Thornton’s color moved from pale to dangerous. “Sir, I… I don’t understand.”

The colonel faced the room. “How many of you know what this patch represents?” Silence answered. “Thought not.” His voice hardened like river rock. “This is the Joint Special Operations Command Distinction Award. It is awarded exclusively to officers who have demonstrated extraordinary leadership and tactical excellence during highly classified special operations missions. In the twenty years since it was established, only five officers in the entire U.S. military have earned it.”

You could hear Preston’s tablet hit the table. Chen looked at me with something like recognition. Harris went stock-still.

“Captain Reeves cannot discuss her previous assignments,” the colonel continued, “because they remain classified at levels none of you—including myself—have access to. The operations she participated in shaped national security outcomes you will read about in thirty years, if then. Any discourtesy you’ve extended stems from ignorance, not malice. Let’s keep it that way.”

“No apology necessary, sir,” I said, because grace costs least when you can afford it. “I’m used to questions.”

The colonel scrolled my slides, interest replacing anger. “This analysis is exceptional. The threat assessment shows tactical insight only gained the hard way.” He looked up. “Let me guess: you’ve planned and executed operations in similar terrain.”

“Yes, sir.”

“The after-action reports you drew from?”

“On operations I participated in, sir,” I said, choosing the narrowest accurate square.

He nodded. “This division just got better. I want your eyes on all existing plans. Your perspective is not optional anymore.”

“Yes, sir.”

He dismissed the meeting. People filed out like they were walking past a mirror they didn’t like and weren’t ready to fix. Chen stopped by me first.

“Captain,” he said. “I owe you an apology. I had no idea.”

“You were respectful,” I said. “That’s all I need.”

Harris hovered. “Ma’am, I—”

“You showed me around and told me the truth,” I said. “Keep doing both.”

Preston approached later, contrition not a costume. “I was wrong,” she said. “I thought the patch meant story, not substance. I won’t make that mistake again.”

“Good,” I said. “Because story without substance gets people hurt.”

Thornton waited for the colonel’s office door to close behind them. Through the glass wall, I could see the conversation you only get once from the right leader at the right time. It looked like humility and consequence.

The division shifted the way units do when they realize their definition of expert was too small. People asked better questions. People listened to answers they didn’t already like. People who had once whispered about a patch drifted by my desk with problems that needed better frameworks and got them.

Part II — The Work

Colonel Daniels called me in the next morning. His office had mementos that weren’t trophies—a rock from a mountain pass soldiers still dream about, a coin from a unit that laughs at funerals because they know better than to cry in front of the young. He didn’t posture. He sat like a man who’s carried other men.

“I requested you,” he said. “I read what I could read. I knew what I couldn’t. I want to change how this division plans. Convergence. Conventional and special. Tactics with patience. I needed someone who knows what the ground smells like and what staff officers forget when they chase timelines instead of outcomes.”

“It’s a good staff,” I said. “They want to be better. That’s unusual.”

He smiled for the first time. “You’re going to make them better.”

We began with comms. Chen and I pulled apart communications redundancy like a mechanic with an engine. We added a second layer of frequency hopping to ensure we could steer around jamming without playing charades on the radio. We gave lieutenants pocket cards they could actually use under fire. We trained majors not to create ten-minute radio checks that cost the mission more than a signal ever could.

We rebuilt our “last mile” logistics plans with the humility of people who know yes is a dangerous answer if you’ve asked the wrong question. We shifted convoys to nights that made sense for the terrain and not the staff duty roster. We elevated a staff sergeant from the motor pool to run a portion of the planning session so officers could hear what happened to planners’ assumptions when a gasket failed in the wrong county. It was possible to tell who had paid attention by how many captains showed up in coveralls for the next brief.

Preston came to me with an op-order draft. She had always been competent. Now she was hunting excellence. “You’d add a deception cell here,” she said, tapping the map, a place any enemy with a pulse would focus.

“And here,” I said, tapping a different place, not because I knew more but because I knew how much I didn’t.

She nodded. “I can’t stop hearing it,” she said. “Only five officers.”

“It’s just a patch,” I said.

She laughed, but it wasn’t unkind. “It’s not just a patch.”

I taught a guest session at the Officer Basic Course after Harris asked for the story he couldn’t have. I gave them everything else: how to set a perimeter that doesn’t forget the part most likely to be walked through; what to tell a private on his third convoy when someone asks him to go faster than safety and slower than common sense; how to smell a plan that only exists to make a PowerPoint look heroic. I didn’t tell them anything classified. I told them what their soldiers needed them to know and what their future selves would thank them for doing. The room asked questions like they were paying attention with their lives. I always like that room.

Thornton came by my desk one Thursday afternoon like a man walking into a freezer he’d avoided. He stood hands-in-pockets, posture less colonel-wannabe, more kid-sent-back-to-say-sorry.

“I’d like to learn,” he said. No theater. No qualifiers. “If you’re willing.”

We started with after-action reports and ended with something like friendship. He told me stories that bent my throat and I told him stories that are not mine alone to tell. He learned faster than he liked admitting. He learned that respect doesn’t travel only with rank or ribbon, it travels with readiness to be wrong.

The colonel brought me a challenge coin one afternoon and set it on my desk like a baptism. JSOC Distinction on one side. Five names on the other. He tapped the metal.

“You’re part of a group that wishes it didn’t exist,” he said.

“I know,” I said. Coins are heavy for reasons that don’t always have to do with metal.

At lunch one day, Chen asked about the patch again—but not the way people used to.

“Does it ever feel like wearing a target?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “It feels like wearing a reminder. Not of me. Of them.” I didn’t have to explain who them was. He’s carried his share.

He nodded. “I figured,” he said. “Your work reads like ballast.”

Three months and the division’s tone had changed enough that visitors relaxed faster. We adopted a few of my protocols across two brigades. We wrote them into the joint exercise because doctrine is not holy unless it helps.

The orders came on a Tuesday afternoon—promotion to major and assignment to a joint task force at CENTCOM, developing operational doctrine that would mean our kids got better plans than we got. I showed the colonel and he grinned like a man whose chessboard was working. He scheduled a ceremony that didn’t try to be a parade.

On the day he pinned gold oak leaves on my collar, the room stood with something like pride and not a little relief that the Army sometimes gets it.

After, Thornton shook my hand. “You changed how I lead,” he said. “That patch didn’t do it. You did.”

“Both can be true,” I said, and he chuckled because humility had finally taught him how to laugh.

Preston hugged me. “I will never again confuse secrecy with laziness,” she said.

Harris gave me a thumb drive of lecture notes and begged me to edit them with the cruelty of truth. “Future lieutenants need what you have,” he said.

“Future lieutenants need what you have,” I said. “The willingness to tell a captain the boss is testing her.”

Part III — Memory Work

Leaving any place you’ve made better hurts in the same place that making it better felt good. I packed. I handed off briefings. I wrote an over-detailed transition memo because the Army deserves at least one. I walked through the building one more time at dawn—floors quiet, coffee not yet strong enough to cover the absence of bodies. The patch on my sleeve had weight that morning. Memory does that.

I stood at the window of conference room B, the one with the weird flicker in the light that someone will finally fix next fiscal year. I let myself think about what I never let myself think about in rooms full of people: the Afghan village at 0300 with the dog that wouldn’t stop barking, the plateau in a country I can’t write down where comms went dumb and a corporal’s hand on my elbow kept me from stepping directly into what would have ended the conversation entirely, the heat that smells the same in every desert, the cold that bites different when a helicopter lifts and leaves you to your work. Faces. Voices. Names I carry and will always carry, the living weight of the dead most days and the other kind on others.

The patch doesn’t mean I’m special. It means I remember.

CENTCOM smells different, sounds different, speaks in acronyms that have longer shadows. Tampa is humid in a way that pretends to be kind. The task force was hungry to be better before they met me. That’s my favorite kind of unit. They had puzzles I’d never seen and pieces I recognized blindfolded. We wrote doctrine with verbs that made sense. We re-learned humility and taught it at the same time.

Sometimes strangers in airports ask about the patch and I tell them it was a gift from a friend I can’t talk about. They laugh because they think I’m joking and I smile because I am and I’m not.

Mom calls now on Sundays and asks me bad questions on purpose so I have to answer with a story instead of a shrug. Dad sends articles I read if the headline doesn’t tell me he won’t like my reply. Blair texts videos of her niece (my niece) singing the alphabet like it’s a threat. The family that measured me by clothes now measures me by whether I can make the next brunch. Progress is hilarious that way.

The colonel emails sometimes, just a line. “Miss your eyes on these plans.” “We added your comms protocol—worked.” Once, “Ran into number three on the coin. He says hello.” I sat with that email in my inbox for an hour before answering. There are families you join whose reunions happen in different rooms.

One afternoon I got a package with no return address. The coin. No note. I held it, named the four other names out loud, like a rosary I’ve never been taught but always known.

Part IV — The Last Briefing

You don’t always get a last act, not the one you’d write for yourself, not the one that wraps things clean. But my last day at Bragg gave me a moment I will keep with the pictures in my wallet.

We did one more briefing in conference room B. Not mine. Harris’s. He’d grown into his rank and his haircut. He ran the room like it was a mission, not a meeting. He presented a supply plan that didn’t make any of the mistakes my teenage self would have. He took questions with calm I recognized. He mispronounced one town name and made a joke about never trusting anyone from Ohio to name a road in North Carolina and the room laughed in a way that wasn’t forced.

At the end, he glanced at me. “Ma’am, would you add anything?”

“No,” I said. “You got it.”

Thornton caught me in the hall. “Drink?” he asked, meaning coffee not whiskey for once. We sat on a bench and watched a formation run past, cadence calling out a song that is always the same and always new.

“Are you ever going to tell me any stories?” he asked.

“I told you the ones that mattered,” I said.

He nodded. “Fair.” He looked at my sleeve. “It doesn’t look heavy.”

“It depends what day you’re asking,” I said.

He put a hand on his own shoulder where a patch would go. “I hope I carry what I’ve learned as well as you carry what you’ve earned.”

“That’s the trick,” I said. “Not to let it carry you in the wrong direction.”

He laughed. “We’re getting better at that here.”

“You are,” I said. “Keep doing that.”

Part V — The Ending That Isn’t

A clear ending is a luxury. The Army prefers transitions. But the day I pinned on major and the colonel shook my hand like he didn’t want to let go, I felt something like an ending that earned itself.

I wrote an email to the five on the coin—three addresses that would bounce, two that would not, all of them to people who might never read them. I wrote the names again. I said thank you without saying why. I said I would keep doing the work.

In Tampa, my desk faces a window that turns afternoon sun into a dare. I keep the coin in a drawer I don’t have to open to know it’s there. I keep a spare patch in a Ziploc. I don’t wear it every day. I don’t need to.

“What’s that patch even for?” a young officer asked recently, eyes curious, not cruel, the way questions sound before a unit teaches them to be answers. I thought about saying it’s for remembering. I thought about saying it’s for quiet work and loud results. I thought about saying it’s for five and more than five.

I said this instead: “It’s a reminder that the person you’re questioning might know things you don’t. Treat them accordingly. Treat everyone accordingly.”

He nodded like a man who would.

Weeks later, the colonel visited Tampa. We slipped out for bad coffee and good silence.

“Only five in twenty years,” he said, more to himself than to me.

“Five is enough,” I said. “If we do our jobs well enough, fewer people have to try.”

He laughed. “Always the doctrine writer.”

“Always the captain,” I said. Rank changes. Work doesn’t.

On my last night before the next assignment, I walked alone on the seawall. The air smelled like salt and aviation fuel. Somewhere a frog tried out a sermon. My phone buzzed. Harris. A picture of a slide—his slide now—with a small note in the margin: “Remember page 14.” I laughed out loud and wiped at my face because the sea air is rude like that.

The patch on my sleeve faded a little more that summer. Good. It’s supposed to.

If the question comes again—what’s that patch even for—I’ll answer like this:

It’s for the kind of work you can’t post about and the kind of leadership that doesn’t need to be announced to be believed. It’s for five names and the hundreds behind them. It’s for planning that saves lives you’ll never meet. It’s for the day a colonel walked into a room and reminded a division what respect looks like when it stands up straight. It’s for the lieutenant who watched and learned. It’s for the major who put his ego down and picked his team up. It’s for the captain who refused to be small when being small would have been easy.

It’s for remembering that only five officers have earned it in twenty years—because very few should ever have to, and because the ones who did would give it back if it meant someone else got to come home.

And then the work continues.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood

HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood …

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her Part I —…

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze Part 1…

My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me

My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me. At dinner, my sister…

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence – That Was Their Biggest Mistake

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence — That Was Their Biggest Mistake Part I —…

My husband & I didn’t finish high school & our son’s wife who graduated from an Ivy looks down on us

My husband & I didn’t finish high school & our son’s wife who graduated from an Ivy looks down on…

End of content

No more pages to load