To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him…

Part One

The morning Michael’s supervisor called the pharmacy, the sky over Portland finally remembered how to be blue.

I had left the apartment late, forgot the umbrella by the door, and jogged the last block to make my shift, the hint of yeast and coffee drifting from the bakery next door. At the counter the regulars lined up with the same paper prescription bags and the same practiced small talk, and for an hour I let my hands go where they knew to go—count, print, staple, smile—until my phone hummed in my pocket like a warning I suddenly understood.

“Hello, is this Julia Dawson?”

“Yes. Who’s calling?”

“This is Brian Simmons. I’m Michael Dawson’s supervisor. There’s been an accident at the site. Your husband was hurt. He’s been taken to Portland General.”

“Is he—” My voice broke in the middle of the verb.

“He’s alive. You should get there now.”

I didn’t even ask Lisa to cover, just met her eyes, grabbed my bag, and ran.

What do you call those corridors in an ER—the ones with the water-stained ceiling tiles and the hand sanitizer dispensers every six feet and a brightness that isn’t light so much as fight? I found a chair and the machines murmured and a clock blinked and I sat inside that thin, sterile time and thought about how my husband was an architectural designer who studied setbacks and egress plans and didn’t climb scaffolding for a living. But of course, clients ask you to walk a site, and of course a stack of drywall doesn’t care what your title is, only where gravity is.

“Mrs. Dawson?” A surgeon with hair mashed down from a cap and eyes that had learned how to tell truths softly reached for the chart in his hand and told me what he could: they’d relieved the pressure, stabilized the damage, did everything you can do when a building decides to borrow somebody’s spine. He couldn’t tell me whether Michael would walk again. He could only say we would know more when Michael woke up.

When they let me see him, he was pale and thinner somehow, like the accident had taken ounces from him as it took feeling.

“Julia,” he whispered.

“I’m here,” I said, taking his hand, pretending my voice didn’t shake.

“I can’t feel them,” he said, looking at the blanket where his legs should have been. “Below my waist. I can’t feel anything.”

“It’s early,” I said, standing upright in a sentence I did not yet trust. “The swelling, the anesthesia. We’ll listen to the doctors. We’ll do the work. I’m with you. We’ll do whatever it takes.”

He closed his eyes and the beeps held us.

The first call I made was to Natalie, our daughter, a sophomore a hundred miles away with a dorm room too small for what she would feel. She offered to drive home and I told her no, to hold steady where she was and let me be the mother who blocked the wind. The second call was to Agnes—my mother-in-law, Michael’s spine inside a woman’s body if you could make a metaphor into a person. She announced she would be on the next bus. “Someone needs to take care of my son,” she said, as if I had spent the morning plucking daisies.

At 7:00 a.m. sharp the next day, she arrived with a wheeled suitcase and a garment bag and the smell of duty like perfume. “I’ll take the guest room,” she said, eyeing the couch I had always apologized for. “Or rather, I’ll make do. You should have thought ahead and prepared a proper space.”

“Coffee?” I asked.

“I brought my own grounds,” she said, which is another way of saying I brought my own way.

At the hospital, she turned into a general. She learned the nurses’ names, used them like rank, adjusted Michael’s blanket every five minutes, scolded the tech for leaving the bed too flat, and told the night nurse the mattress was designed for paper cuts, not spinal trauma. When the PT team arrived, she asked for their credentials. When I suggested we focus on Michael’s breath, she repeated my suggestion louder and pointedly looked at me like a witness to her insight.

I had known Agnes long enough to remember the first dinner she didn’t eat. The night I brought a pie I had braided myself for a woman who doesn’t take sugar and never forgets, she examined me like an architectural drawing and circled every line she didn’t approve of. Before Michael proposed, I overheard her in a kitchen with the lights off telling him I wasn’t extraordinary enough and that life gives you surprises but you don’t have to marry them. At our wedding she toasted me by saying I had “managed to land” a wonderful man. She wore gray.

When Dr. Lee said the word “rehabilitation” and handed me a card for Arthur Blake—a private physical therapist who had a reputation for doing the kind of work that steals miracles—I asked how much it cost and learned I would need to know where money is and where it is not.

“We don’t need some stranger poking him,” Agnes said when I brought it up. “I coached gymnastics for ten years. I know bodies.”

“With respect,” I said, my hands folded so she couldn’t see they were shaking, “this isn’t a sprained ankle. It’s trauma to the spine.”

“I gave birth to him,” she snapped. “I know what his body needs.”

Michael looked at the window and agreed with everyone by staying silent.

I called Arthur and booked him three days a week because you can be outvoted and still move forward if your feet know where love is. We dipped into savings. We adjusted the thermostat and cancelations and expectations. Arthur arrived with equipment and presence, and three times a week he coaxed movement from muscles that had forgotten the word. Agnes hovered with her arms crossed, whispering “waste of time” like a prayer she hoped would come true so she could be right.

Two months of hospital air and coins laid down on a table and hope poured into work: Michael still could not stand. He slept badly, talked little, and kept a bottle hidden beneath the bed the way people hide the thing they think will save them from themselves. I found it changing the sheets, glass cold in my hand, whiskey still in the neck, shame in the shape of a cylinder.

“It helps with the pain,” he said, avoiding my face. “The meds aren’t enough.”

“There are prescriptions for pain,” I said softly. “Things with dosages and oversight. This isn’t about your back, Michael.”

He looked past me at the TV that wasn’t on.

“If you keep numbing instead of working, I can’t—I won’t drown with you,” I said, my voice the smallest and bravest I’ve ever heard it. “I love you, but I won’t sink to prove it.”

Agnes walked in at exactly that moment because she is a playwright with excellent timing and called me a deserter in my own kitchen. I became the kind of woman who doesn’t answer when a storm tells her to wait in it.

A week later Dr. Lee pulled me aside with the file that always looks heavier when you need it to be lighter and said the word “stabilization,” said “surgery,” said “inpatient rehab,” said “not guaranteed,” said “insurance will not cover all of it.” The numbers lined up on the page like a wall. I went to the stairwell and learned how much noise a heart can make without anyone hearing it.

That night I did what women have always done when the ledger doesn’t care about what you owe to love: I made a second column. The next morning I took a lunch break I used to eat and used it to say yes to a job that paid cash on Fridays. The day after, an old classmate named In a walked into the pharmacy wearing a blazer that said she had become someone else and offered me a shift at the boutique hotel she manages downtown. “It isn’t glamorous,” she said. “But the hours play nice with your first job.”

So I worked the pharmacy in the daylight and learned the rhythm of housekeeping after 4:00 p.m.—how to strip a bed and tuck hospital corners so tight it feels like your hands are keeping promises, how to make a bathroom gleam without hating it, how to empty garbage cans and refill people’s faith that they are checked into a life they chose.

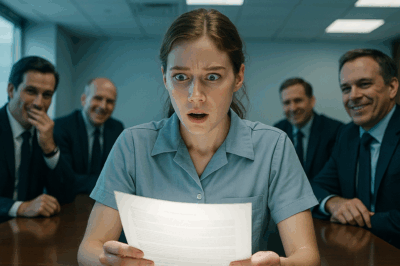

On the tenth day of this new division of myself, I swiped the keycard on 310, said “Housekeeping” in the voice people use when they don’t want to startle a stranger in a towel, and rolled the cart in without looking up because bedsheets do not care who is standing by the window.

He was.

Michael stood without the choreography of pain, without a brace, without his hands searching for a countertop. He stood with a silk-robed girl’s arms looped around his neck and a smile on his face he hadn’t given me in months. She laughed at something private with no hurry in it. He turned at the sound of the cart’s wheels. Our eyes met.

“Julia,” he said.

I backed out, lifted the cart handle like a shield, and learned what it means to walk away from a blast.

He caught up to me on the sidewalk because the elevator always forgets how to come when you need it to and stairs exist for exits and for a man who has been pretending to be too broken to climb them. He called my name and I stopped because I needed to hear what shape a lie takes when it has to stand in daylight.

“It isn’t what you think,” he said, hands up like he was being robbed by a truth he wanted to argue with.

“It looks like you don’t need Arthur,” I said. “It looks like you need a mirror.”

“I was afraid you wouldn’t love me if I couldn’t walk,” he said, and I watched his mouth form the kind of confession people dignify with pity when they don’t have to clean the rooms.

“You let me scrub floors so you could see whether I’d pass your test,” I said, and he winced because even men who use other people’s love to measure themselves sometimes remember shame.

“She’s my boss’s daughter,” he said. “I was trying to get my job back. She said this is how he listens.”

“She said,” I repeated. “You already did the part that matters.”

He reached for me and found air. I drove home through a city that looked the same and felt different and sat down in the living room and found a new ring of the same bell: the phone in my hand lit up with Natalie and a text that said can you talk I’m scared please.

“I’m pregnant,” she said when I answered. “I don’t want to be.”

The room pivoted under me. The wrong man in a hotel fell away. Everything in me that knew how to be a mother stood up.

“You didn’t ruin anything,” I said, because that is the first lie grief tells and the first truth a mother must hand a girl. “You are not alone in this. We will decide together. I will be there tomorrow. We’ll breathe and we’ll make a plan that is about you.”

She cried the kind of crying people do when somebody will sit with them inside a decision.

That night I packed a suitcase in the kitchen because quiet is sometimes more final than a shout and wrote a note to a man who had been pretending to be a story I couldn’t live inside: I told him I would file for divorce. I told him I did not hate him. I told him I no longer recognized him. I told him love does not mean drowning to prove you can.

I slid the note under a paperweight we bought on vacation once because the glass looked like a storm held still, and when the sun came up, I drove toward a campus that still smelled like laundry detergent and pizza at midnight and the life I had built to hold my daughter’s tears.

Part Two

The apartment I found within two weeks had walls thin enough to hear the neighbor’s radio and pipes that groaned like an old man when the shower asked them for hot water. In the morning the eastern light came in slanted and forgiving and made the cheap paint look intentional. The balcony was big enough for two chairs and a gratitude list. It cost less than our old life and gave me back something that had no rent.

Natalie moved in near the end of her second trimester because sometimes bravery is admitting you need somebody to open jars and say “you’re still beautiful” when your ankles don’t believe you. We folded tiny clothes at the same kitchen table where I had written the note to leave a man and learned that when grief and joy sit down together, they end up being very polite to each other. Some nights we laughed at nothing until we cried. Some nights we cried at everything until we laughed. I taught her how to roast chicken and she taught me how to set up a baby registry without accidentally telling the internet you want a giraffe.

She wanted every option and no option. “I’m a bad person,” she said once when sleep made her mouth cruel to her heart. “I thought about not having him.”

“You thought about a hundred futures and chose one,” I said. “That’s not bad. That’s adulthood.”

She named him Elijah because her hands liked the way the name felt and because it sounds like a boy who will learn how to stand even when the world bends. When he came on a rain-pale afternoon in March, the sky washed the roofs clean and somebody put on a playlist that made the nurses hum and I held her hand through the kind of pain that makes you invent new gods and when they put him on her chest he screamed the way the living do when they find out how much it hurts to arrive.

He was beautiful the way every grandchild is: small and angry and perfect. He wrinkled his face and looked exactly like nobody and like everybody in my house. When I held him later by the window at home and the thin curtains turned the light honey, I whispered a verse I hadn’t used since my grandmother died—the kind that says God isn’t ashamed to be thanked in kitchens. He heals the brokenhearted and binds up their wounds, and my chest didn’t break when I said it. It softened.

The divorce moved along the way a boat moves on a river that thinks it is in charge. Papers in envelopes. Courtrooms that smell like dust and decisions. Michael cycled through three lawyers and two versions of himself: the contrite man with a cane and the indignant man with a tan. He asked for grace like it was something you can purchase in a packet at a pharmacy and demanded concessions like a man ordering breakfast. The judge met my eyes and saw a woman who had worked two jobs to buy her husband back a body he used to walk into a hotel, and I did not have to explain.

Agnes called me an ungrateful quitter and then found a support group for women whose sons had become strangers and called me six months later to say she had learned a new word for sorrow and it was forgiveness. We met in the parking lot of a grocery store and hugged harder than either of us expected, and in that brief crumpling of pride, I began to believe we would be okay.

Arthur sent a note on a postcard that had a mountain on it and too much sky and said he was sorry he had been part of a story that hurt me and that if I ever needed a PT friend, the kind who can fix backs and broken chairs, he owed me one.

In the meantime, the boutique hotel taught me things I’m certain I was born knowing and had merely forgotten: how to make a room ready for a person to lay down their bones and trust a bed, how to flatten sheets so clean it feels like a kind of mercy, how to leave a small chocolate on a folded towel and call it hospitality. In the rooms with the view, I learned to look out and thank a horizon for being exactly where it said it would be each day.

In a promoted me to housekeeping supervisor because I do not know how to do a job halfway. She gave me a set of radios and a clipboard and a staff who taught me curse words in languages I want to visit someday. At the pharmacy I moved from the register to tech because my hands know math and mercy. At night I slept in a bed no one had lied in and learned to love the sound of a baby dreaming in the next room.

One afternoon, weeks after Elijah’s colicky phase let us off on a beautiful highway called Sleep, I took him out to the balcony and introduced him to the lemon tree in a terracotta pot I bought from a man who didn’t believe I could keep anything alive. He tried to eat a leaf and I took it out of his mouth and told him he was the best thing I know how to love anyway. In the doorway Natalie watched me watching him and said, “I’m scared I won’t be enough.”

“You won’t,” I said, and she startled like I had slapped her. I reached for her hand. “None of us are. That’s why families are made of more than one person.”

The first time we ran into Michael in a grocery store, Elijah was five months old and had a laugh like a bell. Michael had a limp I couldn’t tell if he had invented or earned. We said hello and it sounded like getting your teeth cleaned. He looked at Elijah and didn’t ask to hold him, which made everything easier. He told me he was seeing someone new, which did not fill me with anything but relief. He said he was sorry for the hotel and I told him I believed him and did not want his apology to bootstrap a conversation about how we might be able to respect each other’s futures. He said okay, like a man laying down a shovel.

A month later a letter arrived from an attorney with paper that felt like it ought to matter. It was a claim against Michael filed by the company whose insurance had paid for a back they thought was still broken. I forwarded it to his new address and left it there. There’s a limit to the number of stories you can be in without losing your own.

The hotel became the kind of place that people write about online when they want to be nice. Ina called me to the lobby one afternoon and pointed to a couple my age clasping hands like they were in a movie. “They’re on their first trip after his accident,” she whispered. “They saved for a year. Upgraded them to a corner room?” I nodded and texted housekeeping to fold the towels into swans because sometimes cliché is exactly what your heart wants. I put a note on the pillow that said you’re doing so well at this and a wrapped chocolate that Elise from nights had brought in from a bakery that adds salt to everything. They cried in the hallway the next morning in a way that let me believe maybe God reads hotel review sites.

Natalie enrolled in a few classes again, the kind you can take with a baby if the baby knows how to sleep at 1:00 p.m. and can be bribed with crinkly paper. She majored in “do not quit on yourself” and minored in “ask for help” and finished the semester with a GPA that made her blush. We celebrated on the balcony with lemonade that tasted like we had earned it.

I heard from Ina that our hotel has a policy about not getting involved in guests’ business unless they ask. I broke it once. A woman checked in with a bruise that looked like a map. She asked for extra towels and looked at me like a person begging a stranger to save her without saying the word please. I handed her a stack I had padded with a card I keep in my pocket with a phone number and the name of a shelter and my own number with the words I will drive written below. She put it in her book and checked out two days later and sent me a text that said I left and I cried into the towel closet because the sheet smell tastes like a sacrament if you hold it together too long.

One evening when the sky decided to be embarrassing about the colors it can make, Agnes arrived at our door with a pie she had bought—bought—and a plastic fork and said she was sorry for being afraid in my direction. She asked if she could hold Elijah and he obliged her by grabbing her pearl earring and trying to eat it. She laughed and said she forgave herself for loving her son so hard it came out wrong. We sat on the floor on a blanket he had already spit up on and learned each other all over again.

I thought about the night on Hawthorne when the sun came through the clouds like a promise and a man began pretending his own legs didn’t work and what rent costs when it’s paid in trust. I thought about a second phone ringing like a prophecy and a girl on a screen who was not a threat but a family letter in a different envelope. I thought about how many times I said yes to something that hurt me because I believed love meant carrying a weight until it broke me, and how many more times I have said yes to something that healed me because I finally believed love is a table you set for more people than you think you can feed.

On the anniversary of Michael’s accident, Natalie asked if we could stop calling it that. “What then?” I asked.

“The day we found our way,” she said, bouncing Elijah on her hip while he practiced his consonants by scolding a lemon. We made a cake. We turned off our phones. We ate on plates my grandmother left me. We told the story of how Nana kept tea bags in a tin and bravery in a jar and how we keep both now because you need both now.

That night I stood on the balcony with Elijah asleep on my chest and the thin curtain pressing into my calves, and I realized there is a particular kind of quiet that belongs only to people who survived themselves. It is not the hush of fear or the pause of waiting for permission. It is the rest of a soul that knows what it can carry and what it can let go.

Somebody once told me that God binds wounds but does not erase scars. I am grateful for that. The scar is a map I read when I forget the story. It runs from the pharmacy to the hospital, from a bottle under a bed to a housekeeping cart in 310, from a call I answered to a phone I no longer fear, from a lemon tree that should not be growing as well as it is to a baby who is the size of a lemon and louder.

We did not end where we planned to. We ended somewhere we could not have imagined. It is better than the plan, which is an act of mercy I am learning how to recognize.

If you asked me now why I took the job at the hotel, I would say “to afford a surgery” and “to save a life” and mean both things in two different ways. If you asked me about the day I saw him standing by the window, I would say, “that was the day I began to see myself.” And if you asked me where we are going next, I would point to a kitchen with two phones charging and a balcony where the morning catches what we forgot to be grateful for, and I would say, “forward.”

END!

News

“Mister, please take my little sister, she’s only six months old and very hungry.” Ethan turned and saw a 7-year-old boy holding a tiny baby close. ch2

The city’s pulse was a frantic drum against Ethan’s ribs. Time was a thief, and it was currently picking his pocket…

The Waitress Said, “My Mother Has the Same Ring.” — The Millionaire Looked at Her and Froze. ch2

Graham Thompson, the 53-year-old founder of Thompson Grand Hotels, sat alone at a corner window table in The Beacon, a warm, wood-paneled…

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… CH2

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… Part One…

My Son’s Family Left Me Stranded on the Highway — So I Sold Their House Without a Second Thought… ch2

Everything began about six months ago, when my son Ethan called me sobbing. “Mom, we’re in trouble,” he choked out,…

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract… CH2

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract……

At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was… CH2

At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was… Part…

End of content

No more pages to load