They Sold My Late Husband’s Rolex To Fund Their Luxury Vacation. The Pawn Shop Owner Called Me…

Part One

The pawn shop owner called me in the middle of rinsing Frank’s coffee mug.

“Mrs. Sullivan?” A man’s voice—careful, steady, like he’d practiced the line on a sticky note by the phone. “My name’s Danny. I run Golden State Pawn on Milwaukee. I think… I think I have something of your husband’s.”

My hand tightened around the porcelain. We were six months into the ritual I still did without thinking: rinse his mug, set it beside the sink to dry, let the air fill with the smell of a man who wasn’t there. It should have been comforting. Today it tasted like pennies.

“My husband died in January,” I said, too flat for a condolence call.

“I’m sorry for your loss,” he said automatically, then rushed, “A gentleman sold us a vintage Rolex yesterday—old Submariner, serials cleaned up, late ‘70s or thereabout. The back plate had a custom service mark. ‘FS’. We opened it to clean it and, well—there’s something you should see. If you want.”

I didn’t ask how he got my number. I didn’t need to. In my kitchen, an hour earlier, my son had stood with his arms crossed, delivering betrayal like a line from a play he’d practiced.

“Stop whining. It’s already sold. I needed that money for our Italy trip.”

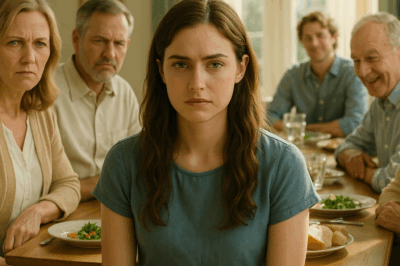

He’d said it so calmly I almost believed him. He’d said it standing under Frank’s photograph, the one where Frank’s laugh lines looked like parentheses around his mouth. Mike had always liked standing in my kitchen to deliver his pronouncements—stood there when he’d announced he and Ashley “couldn’t be running over all the time,” stood there when he’d told me what Frank would have wanted at the funeral, stood there this morning and told me his father’s watch was “just a watch.”

“Which pawn shop?” I’d asked, and Ashley had smiled over her phone like a cat.

“See? She’s being reasonable,” she’d cooed, already half-turned to admire her reflection in the dark microwave door. “Clinging to material possessions isn’t healthy, Dorothy. Therapy might help.”

They hadn’t even closed the door gently when they left. The house held their echo and the smell of their perfume and a version of my own patience I didn’t recognize. I had been a bank manager for forty years. I could smell bad paper across a counter. You don’t survive thirty years in risk management by folding at the first sign of guilt.

“Mrs. Sullivan?” Danny’s voice again, in my ear. “Do you think you could come by?”

“I’m on my way.”

Golden State Pawn was the kind of place that smelled like old metal and stories people didn’t want anymore. Fluorescent lighting cast everything in a hospital pallor. Behind thick glass, jewelry winked like secrets trying to be noticed.

Danny looked younger than I expected; all tattoos and guarded kindness. He had the careful hands of a man who knew how to handle other people’s desperation.

“You sold it to my son for eight hundred,” I said, before he could pitch me a policy. “He didn’t ask.”

His mouth twisted. “He said you might show up. Said you were… having a hard time letting go.”

“If by letting go you mean trying not to drown standing up, then yes,” I said, and was startled by my own bite. Danny winced—not at me, but at the situation. He slid a small manila envelope across the counter like a conspirator passing a note.

“When we opened the case to service it, there was a…professional job. Hidden pocket behind the rotor. Never seen one so clean. Inside was this.”

I unfolded the paper. Frank’s handwriting hit me like a scent. Precise. Careful. The letters leaned forward, always.

Dorothy’s birthday, July 15, 1955. The day I knew I’d marry her.

Underneath, a string of characters: SS4457 CH0815 DS.

I could hear Frank—don’t panic, Dot. Think. The numbers sat there like a door in a wall. SS. CH. 0815. DS. Minimalist, smug, sure I’d recognize the shape.

“Who bought it?” I asked.

“Paid cash,” Danny said. No apology, just tired truth. “Asked after ‘70s Submariners. Mentioned cleaning. When I said we found something, his eyes got real interested. He left fast after he counted the bills.”

“Did he give a name?” I asked.

“Not to me.”

I slipped Frank’s note back into the envelope. “If he comes back, you never saw me.”

Danny held my gaze, then nodded once. That was all.

On the drive home, the paper felt hot in my purse, like it might burn a hole and set the front seat on fire. The house looked the same as it always did—front walk too neat, azaleas half-hearted against the brick—but when I stepped inside Frank’s office, the air changed. He had organized everything into careful stacks like a mind could be filed. Forty-three years of order stared back at me. I stared back.

SS. CH. 0815. DS.

SS—Social Security? No. Frank’s began with 457. CH—Chicago. Or…CH could be a bank. 08/15—our anniversary. Not my birthdate, despite the line above. Frank loved to hide romantic things in plain sight. He’d made me a treasure of our own story and not told me.

I pulled out a laptop and the confidence of a woman who had once closed a hole in a loan portfolio so stubborn it had a personality. I searched for banking conventions, offshores, weird boutique investment naming protocols. Secure Solutions Investment Management—Cayman Islands—tiny web presence, guarded client portal. They wanted a client code and a password. I typed SS4457CH0815DS in the first field. Blue stretched into green. The screen changed.

Valid client number.

The password prompt blinked at me like a raised eyebrow. Frank had been a fan of small jokes. I tried our address. Our wedding date. No. Then I heard him, smiling over a bad ribeye in 1974: “Not your birthday, Dot. The day I knew.”

July 15, 1955. 071555. Access granted.

The number did not make sense at first. It sat there in black on white, obscene.

$2,847,029.67.

I was not a woman easily shocked. I had sat across from grown men and told them they were approved for a mortgage and then told them their wives were not listed on the deed because the men had asked me not to and I had told them no with the authority of a notarized stamp. My face didn’t move easily. But I had to sit down in Frank’s chair and make my body small around the explosion in my chest.

Forty years of “we should wait on that vacation” and “do we need the good olive oil?” turned into investments not in yachts or beach houses but in something Frank had believed worth hiding. They weren’t huge deposits, the early ones. Five hundred here, a thousand there. Then in the last year, big numbers with notes that tasted like code when I said them out loud: Real estate liquidation. Emergency.

Another folder waited under Messages: FOR DOROTHY – EMERGENCY ACCESS ONLY.

I clicked. Frank’s face appeared on the screen. There’s a way men look at you when they know they have to say something you won’t want to hear and love you enough to learn how to say it well. He looked at me that way.

“Dorothy,” he said. “If you’re watching this, I’m gone. And something’s gone wrong.”

He rubbed his temple, the same way he had when the transmission on the Ford had given up the ghost.

“The money isn’t mine,” he said. “It was my father’s, hidden before he died. He saw the Depression hollow men out and wanted a lifeboat no one could steal. He made me promise. I kept it. And I grew it. Carefully.”

He looked up at something just above the camera. His mouth softened.

“I hoped you’d never need it,” he said. “But I think you might. I’m sorry for keeping this. You deserved to know. I didn’t tell you because I needed to keep it from someone else. Thomas will explain.”

Thomas. The name flickered. The private investigator who’d stood by Frank’s coffin and shook my hand and looked like he’d swallow a secret whole before he’d let anyone make me swallow one. The man Frank had introduced as “old friend” and refused to elaborate.

I called him the next morning. “Frank told me you’d call,” Thomas Chen said, as if this were a meeting over a sandwich instead of a breach in my life. “He left you a package. He left you protection.”

“What kind?” I asked.

“The kind that makes men in suits sweat.”

He was not exaggerating.

In Thomas’s office, under glass and pine and expensive floor wax, lay a file that was both a roadmap and a minefield. The map showed my son’s debts—a tangle of offshore gambling accounts, quick loans with Gothic interest rates, fraudulent income on business applications, a whisper campaign Ashley had started about my “confusion” (neighbors too polite to ask and too eager to believe). The minefield was the one Frank had laid under Mike’s feet: asset transfer triggers that would light up if Mike tried to challenge my competency, trust structures that would pour money into a children’s hospital if Mike attempted to touch them, recordings—audio, video—of kitchen conversations Mike and Ashley had had under my roof when they thought grief had made me deaf.

“Your husband wired the house for sound the week after he hired me,” Thomas said, not looking apologetic when my jaw tightened. “He hated doing it. He said you would hate it too. He wanted you safe more than he wanted you to like him.”

“He would have told me,” I said, and felt the lie like a stone in my mouth. Frank had been a man who folded in on himself when afraid. He had not known how to say “our son is a thief.”

“Mike’s been researching how to have you declared incompetent since October,” Thomas said. “He’s met with three lawyers and one doctor who will sign anything for a check. He’s been working on Ashley, too. Good wives talk to neighbors. The neighbors talk to each other.” Thomas pushed a folder across the desk. “Frank made it so any move your son makes triggers a donation to a place that saves kids. He chose the hospital because he knew it would kill Mike not to get the credit.”

I barked a laugh. It came up like a cough and turned into something dangerously close to crying. I swallowed it. There would be time to cry when I wasn’t a target.

“File everything,” I said. “All at once. Start with the FBI. Then the state’s attorney. Then let the IRS have dessert.”

Thomas nodded. He slid a sealed envelope across the desk. “One more thing. Frank wrote you a letter. Don’t read it until you’re sure.”

I didn’t get to wait. Mike and Ashley turned up forty-eight hours later, suitcases rolling, Ashley in sunglasses as wide as her intentions. They stood in my bedroom doorway like two realtors arriving to show me out of my own life.

“We just wanted to say goodbye,” Ashley sang, as if we were traders in pleasantries and not grievances.

“What are you working on?” Mike asked, eyes already scanning Frank’s desk like a boy who had learned where candy was hidden and never unlearned it. He had my father’s jaw and none of my father’s honor. He took a step toward the computer. I put my hand on the screen and closed it gently.

“Your father left me a message,” I said. “No, you cannot see it.”

Ashley moved faster than I’d given her credit for. “Mike, she said—”

“She said ‘message,’ Ashley,” Mike snapped, then turned back, voice modulated to patient, concerned son. “Mom, this is hard for all of us. Let me help.”

“Help,” I said. “Is that what you call selling your father’s watch?”

He flinched. Ashley didn’t. “We needed the money for Italy.”

“You needed the money to escape the net tightening around your neck,” I said. “And you are sloppy fishermen, Michael. This is me telling you that I see the lines you’ve thrown.”

Ashley took a long breath through her nose, a horse considering whether to bolt or bite. She decided on bite. “You crazy old woman, you don’t—”

“Stop,” I said, and she did. Not because I was commanding. Because through the window behind me two black SUVs had rolled to the curb and men in windbreakers were walking up my path with the confidence of men whose paperwork was in order.

Ashley went pale. “What did you—”

“I documented,” I said, and then the doorbell rang.

There is a particular silence in a neighborhood when law enforcement arrives. Curtains shift, dogs stop barking, the casserole in Mrs. Patterson’s oven across the street burns without anyone opening the door to check. The agents filed in like a well-rehearsed apology. They had questions for Mike and papers for Ashley.

“Elder abuse, fraud, attempted theft, conspiracy,” an agent said, reading from a list in a voice designed to be heard and not remembered.

Mike kept it together for three minutes and then cried like the boy who had skinned his knee, except now the knee was his future and I did not have antiseptic or a bandage big enough.

“This will destroy us,” he said into his hands.

“You did that,” I said, not cruel. Just precise.

He called me from the back of a car, and for a flicker of a moment my heart broke along old fault lines. “Mom, please. I never meant it to go this far.”

“‘This far’ is a measurement taken by people who didn’t look before they leapt,” I said, and then I hung up before the apologies I had waited a lifetime to hear could be trotted out like floats in a parade too late in the season.

The days that followed were a sorting of piles. The FBI carried computers out of Mike’s house like coffins. The IRS showed up with a smile and a pen. Ashley screamed at anyone who would listen; when that became tiresome, she went quiet. I found my granddaughter Melissa on my porch one evening with eyes like her father’s and a heart that beat like mine.

“I’m so sorry,” she said. “I knew something was wrong, and I didn’t know what to do.”

“You did the right thing by coming,” I said. We ate spaghetti and she told me about her classroom, twenty-six second-graders with mouths like sparrows and attention spans like fireworks. She cleared the plates and I told her about Frank’s watch, the hidden compartment, the second hidden compartment a retired marshal had brought to Thomas’s office two weeks later with an SD card that had everything: audio of my son’s plans, video of his meetings, the entire conspiracy preserved not like a threat but like insurance. The marshal had explained Frank’s instructions: if Mike ever tried to move me onto a chess square I hadn’t chosen, the hospital got a wing and Mike got a cell.

“Grandpa was… something,” Melissa said, in the voice of a girl who is just now learning her grandparents had lives bigger than the word. “So are you, Grandma.”

I wore Frank’s watch that night and wound it between my forefinger and thumb the way he had taught me. The ritual felt like a prayer, and for the first time since January, it didn’t taste like pennies. It tasted like the first good olive oil we’d bought when we could afford two bottles of something: one for everyday and one for occasions.

I opened Frank’s final envelope then. “You can forgive him,” he had written, “or you can let him face the consequences. The choice is yours.”

I chose both.

I let the state prosecute Mike and Ashley, their charges a neatly stacked mailing tower: elder abuse, fraud, conspiracy, with “attempted murder” penciled on the side by a detective who had taken one look at the lab report on the champagne and then looked at me like she wished she could go back in time and catch the poison as it hit the glass. Jessica—no, Ashley—took eighteen months. Mike took two years and a lifetime of restitution. The court ordered his company’s assets liquidated. Frank’s booby-trap trust emptied what remained into the children’s hospital with Mike’s name on the plaque and “funded by Dorothy Sullivan” in a font a little larger than his. It wasn’t petty. It was fair.

I forgave Mike in the only way forgiveness has ever made sense to me: I took away the power his harm had over my days. I cooked when I wanted to. I joined three book clubs. I donated money to the hospital wing and named the playroom after Frank because if money can make anything right, it’s a room where sick children forget their bodies for ten minutes.

The pawn shop called me again at the end of summer. “Mrs. Sullivan,” Danny said, “you should know the guy who bought your husband’s watch left a note for you. He said he didn’t buy the watch. He bought the man who owned it. He said tell her the right people knew to call because the right woman knew where to hide a note.” He read the note over the phone. “Thank you for telling me the champagne tasted funny,” it said. “The next buyer might not have noticed.”

“Tell him thank you,” I said, and hung up and took my granddaughter to the park.

Frank saved us by listening more than he spoke. I saved myself by remembering his lesson. Mike tried to make my life about his failures; I made it about my choices. The watch keeps time like grief does: not in minutes, but in rituals. I wind it. It winds me.

Part Two

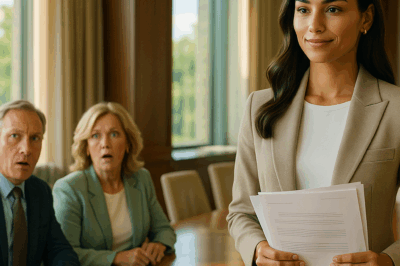

There’s a particular sound a courtroom makes when a prosecutor stops talking. It’s the sound of breath being suspended collectively—not held (that’s fear), not exhaled (that’s relief), suspended, as if everyone in the room has agreed to let gravity decide.

Mike stood when the judge told him to stand. He wore a suit he didn’t buy (public defender’s budget, not his) and a face that tried on remorse like a suit jacket over a T-shirt. The judge spoke in the even cadence of a man who’d said the same sentence to too many people.

“Mr. Sullivan, you took what was not yours, and when you couldn’t take it with a signature, you tried to take it with a lie. This court sentences you to twenty-four months in federal custody, followed by five years probation and full restitution. The elder in your life afforded you care; the least you can offer her now is distance.”

Ashley cried loud and then quieter and eventually in a way that made less sense to her and more sense to the oxygen in the room. Sentences are punctuation; people adapt.

I did not attend. I did not need to be in the room to be recognized by the state. I went to the hospital instead and watched the plastic coverings go up over what would be the Frank Sullivan Memorial Wing. A project manager—sober, efficient—walked me through with a clipboard. “There’ll be a reading room here,” she said, pointing to a corner where sunlight pooled like a cat. “And the chemo bay is down this hall. We’ve left the window low so the kids can see the trees.” She said it like it was pragmatic. It felt like holiness.

“Thank you for telling me about the low windows,” I said, and she blinked as if I’d blessed her.

Frank’s lawyer, Thomas Chen, called two days later to tell me Ashley had taken her eighteen months and a plea and an agreement to never again manage anyone else’s money. “You should know the state will likely pursue additional counts if she breaches any part of her probation,” Thomas said. He had become a friend by then, one of those odd friendships born of crisis—two people bound not by history but by the relief of competence.

He also told me about a box that had sat at his office more months than he’d meant to let it sit. “A retired marshal came in with your husband’s old watch and something else, something we didn’t realize was there—a second hidden compartment. There was an SD card. Frank left us everything. We handed it to the FBI. They called it overkill.”

“Frank never did kill one thing when he could kill three,” I said, and both of us laughed, and the sound made the line click back into a feeling that wasn’t grief; it was gratitude colored by the first degrees of joy.

If there was one nagging thread left, it was the man who had first bought the watch. When Melissa visited on Sundays, we would sometimes spot a well-dressed older man walking past my house at the time of day when shadows make everything an outline. He would tip his hat—a gesture too old-fashioned to be fashion. Once, he stopped at my gate and didn’t open it.

“You were married to a careful man,” he said, not asking, telling me. “Careful men are rare.”

“You’re married to a careful job,” I said, natural instinct telling me not to ask him to define it.

He nodded. “He made sure your grandchildren would understand what honest money is. Not all men can do that.”

He left. The watch on my wrist ticked on quietly, its sound a metronome for a life I had learned to live at my own tempo.

Melissa teaches second grade the way a field commander allocates resources: everyone gets what they need, not what they want. She told me once that if you show a kid where to put their feelings, you rarely have to show them twice. I told her there were grown men who could use her class.

On a blue Tuesday, she brought ramen over and told me about a boy named Antonio who had drawn a picture of a dog that looked like a dragon. “He said he wanted the dog to look big enough to scare sadness away,” she said. “How do you grade that?”

“You give him a sticker the size of a moon,” I said.

“Grandma,” she said, serious now. “I want to ask you something. If Dad writes to you from prison, will you write back?”

I had been thinking about that question long enough not to answer it like it was new.

“I will read his letters,” I said. “I might answer one. I will likely not answer all. I will not apologize for either choice.”

She nodded. “I guess forgiveness looks different on different people.”

“It looks like peace,” I said, “or it isn’t forgiveness.”

She nodded again and then changed the subject ruthlessly, the way women do when they open a door to an ache and then decide to shut it before the wind changes all the furniture. “Tell me about Southern Italy,” she said brightly, the idea of a trip resurfacing.

“I’ve been thinking Greece,” I said. “Frank never wanted to go somewhere he couldn’t order without pointing at a picture.”

“Greek islands.” She sighed. “You’re going to flirt with a fisherman.”

“I’m going to flirt with a waitress and tip her double when she tells me where the good places are,” I said.

We bought tickets that night. When the plane lifted off, I closed my eyes and let the sound of the engines teach me a new prayer.

The phone call came from a number my bones recognized before my brain did. “Mom,” Mike said. The word was the same, but the mouth had learned a different taste for it.

“Hello,” I said.

“They’ll let me out in eight months,” he said. “I’ll have to take the bus to a halfway house. I… would you meet me for coffee? Not at your house. Not at mine. Just—a diner?”

I looked at the watch. It was a Tuesday. The hospital wing would still be there tomorrow. The book club would forgive me for missing a discussion about a book none of us liked anyway.

“Pick a place,” I said. “And be on time.”

He was. He sat in a booth with his hands folded like a kid waiting to be scolded and not quite ready to confess. He looked thin; prison takes weight off men who ate their feelings and leaves only the feelings. He wore cheaper shoes. He looked like my son in a photograph I kept in a drawer—the one where he had a black eye from a baseball and let me put frozen peas on it while he cried and pretended to be brave.

“I’m sorry,” he said, not in the tone of a boy caught; in the tone of a man who had learned something expensive. “I’m not asking for anything. I wanted to say it.”

I put my coffee down.

“You tried to make me into an account,” I said—no heat, just record. “I won’t ever be that for you. If you want a mother, you’ll have to be a man who knows what that word means.”

He nodded. He didn’t argue. That was new.

“Granddaughter tells me you’re volunteering at the hospital,” he said, and the corners of his mouth twitched like he wanted permission to be human.

“She tells me you’ve learned to mop,” I said.

He laughed. It wasn’t the laugh I knew. It was quieter and earned.

We sat like that for a half hour. When we left, we agreed on nothing except that he would send a letter to the hospital thanking them for letting me volunteer. “No mention of you making a donation,” I said, and he nodded. We walked in different directions.

At home, I wound the watch and wrote a check to the schools where Melissa taught. When I put the pen down, the house was not silent the way it had been after Frank died. It was quiet the way a room is quiet when it finally holds only furniture you chose.

A year after Danny called me about the watch, he called again. His voice had changed too—some weights move after you’ve watched a small thread pull a whole tapestry apart.

“The guy who first bought the Rolex came back,” he said. “He wanted me to tell you something. Said ‘tell her the right men watched the pawn shop because they knew it mattered to someone who had done something valuable with a life.’ He said he was trying to keep a promise to your husband.”

“Tell him I said thank you,” I said, and put the phone down and cried for exactly the length of Frank’s favorite Sinatra song. Then I laughed when I remembered that Frank didn’t like Sinatra; he just liked the idea of being a man who liked Sinatra.

On the day the hospital wing opened fully, they asked me to cut a ribbon I didn’t need to cut. I told them kids didn’t need pomp; they needed low windows and shots that didn’t sting as much. They cut the ribbon anyway. The plaque gleamed, names etched in brass, the hospital’s thanks public and sincere. A reporter asked me what I wanted people to take away from the story. “That protection is love,” I said, “not control.” She nodded like she understood. If she didn’t, it didn’t matter. The windows were still low.

At night, the house and I have learned to breathe together. I wind the watch. I water the geraniums. I mail checks and sign petitions. Sometimes I find myself standing in front of Frank’s photograph and saying nothing, which is what we were best at when we were not arguing. Other times I speak out loud to the memory of him and tell him the plot twist of the week. “You would have hated Greece,” I tell him. “Too many cats. I loved it.”

I write letters to women who DM me because my granddaughter insisted I start an Instagram to show “grandma chic.” They tell me their sons are circling. They tell me their daughters-in-law smell like blood. I tell them to file things. I tell them to document every conversation and to get a lawyer who is not a friend of the family. I tell them to listen to the taste in their mouth when someone tells them that grief has an expiration date. “It tastes like pennies,” I write, “but you can spit it out.”

Sometimes in the morning I hold the watch and for a second it feels like Frank’s hand is there: strong, callused, absolutely sure he can fix anything if given enough time and a drawer full of screws. It is magic, of a sort. Not the kind that moves mountains. The kind that helps a woman do the dishes while the roar of her life quiets to a hum she can sleep to.

They sold my late husband’s Rolex to fund their luxury vacation. The pawn shop owner called me. The watch came home. The money kept time. The law kept pace. And I—well, I learned that love foresees, betrayal galvanizes, and old women who look small in their kitchens can still weigh more than a son expects when she finally insists on being counted.

If you’ve read this far, I hope you’ll remember this part more than any bank account number or legal term: if someone tries to turn you into a line item, refuse the audit. You are the ledger. You are the whole book. Woe to anyone who learns that too late.

And if a man calls you about a watch, answer. It might be a clock. It might be a compass. Either way, it will point true.

END!

News

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. ch2

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. But… Part One…

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me. ch2

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… Part…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong. CH2

My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong Part One The roast…

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. CH2

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. Part One…

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… CH2

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… Part One The hallway outside my…

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One. CH2

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load