The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me.

Part One

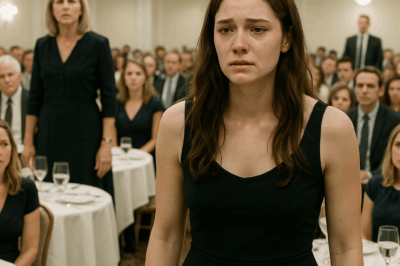

The room was so quiet you could hear the tick of Grandma’s brass clock on the mantel and the soft sigh of the furnace pushing lavender-scented air through the vents. Fifteen relatives sat crammed into her living room, knees touching, shoes lined up like obedient children by the door. I was thirty-two and in my usual chair by the window—one that resigned itself to drafts and disapproval—when my sister stood up in her tailored suit and announced she was tripling my rent.

“Sixty-eight hundred,” Victoria said as if she were handing down a sentence. “Effective next month.”

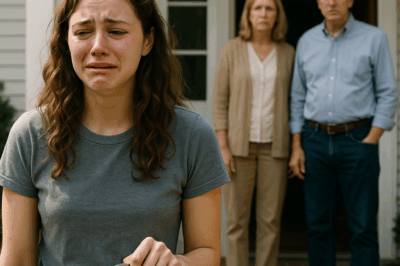

Aunt Patricia made a low, appreciative sound. Cousin Derek smirked. My parents didn’t flinch. The silence of my father’s clasped hands and my mother’s unreadable eyes weighed more than my sister’s voice ever could.

I kept folding laundry on my lap because I needed something to do with my hands. I smoothed the collar of a button-down I’d ironed earlier and set it on the finished pile. I already knew something Victoria didn’t. And her speech—its cadence, the deliberateness of each blow—was almost a relief. We were finally saying out loud what the family had decided a long time ago: her word shaped the world and mine didn’t.

“Your current rent is twenty-two hundred, far below market,” she continued, flipping to a page of color-printed graphs. “Comparable units on Riverside are going for seventy-two, seventy-five, even eight thousand. I’ve subsidized your lifestyle for five years.”

Aunt Patricia touched her pearls like Victoria had personally rescued a child from a burning building. “So generous,” she murmured, loud enough for everyone to hear.

“It isn’t generosity,” Victoria said. “It’s fairness. Madison, you’re thirty-two. It’s time to stand on your own feet.”

The irony of being lectured about standing on my own feet while the floor shifted under me wasn’t lost.

Every family gathering had followed the same script my whole life. Victoria was the golden one—summa cum laude, Harvard Law, making partner at thirty-five, photographed in magazines with a quote about tenacity. I was the ordinary one—state school, property management degree, assistant manager at a midsize firm—doing “that property thing” my aunt never bothered to name.

It wasn’t that I hated my work. I loved it. I loved walking buildings no one else saw value in and imagining new paint, new pipes, new lives; I loved spreadsheets that made sense and roofs that didn’t leak. But fascination isn’t currency in a family that only values headlines.

“Sign the new lease,” Victoria said, clicking her pen and sliding paper across the coffee table toward me.

I looked at the number—$6,800—and felt my heart thud once and then settle into an even rhythm. My phone on the side table buzzed exactly once. I didn’t need to look. The text I’d sent twenty minutes earlier—On my way, documents ready—had received a yes.

“Let me make this educational for everyone,” Victoria said, turning toward the mantel like it was a lecture hall. “Here’s what Madison’s apartment should cost.” She flipped through Zillow listings with an index finger manicured to a point. “Seventy-two hundred, seventy-five, eight thousand. I’m giving her a discount.”

“Guess you’ll need three roommates,” Derek stage-whispered. It was the least creative thing he could have said. It still stung.

No one objected. Not my mother, who smoothed her skirt. Not my father, who studied his interlaced fingers as though they were new. Their quiet hurt worse than the numbers. Silence can be loyalty, I suppose. It can also be permission.

I set the lease down and placed the pen neatly beside it. “No.”

It wasn’t loud. It didn’t need to be. The word cut like a knife through paper.

“What do you mean no?” Victoria’s smile faltered. Her power had always depended on people accepting the premise that she had it.

“I mean,” I said, letting the words sit on my tongue long enough to flavor them with calm, “you don’t have the authority to raise my rent.”

She laughed, and the family laughed with her because that was what we did—a chorus to her solo. “Madison, I manage this building. I set market-rate rents. I’ve already got three applications from Columbia Law students offering seven thousand. Either sign, or start packing.”

The doorbell rang.

I stood. My hands were steady as I tucked a loose seam in my sweater and crossed the room. Aunt Patricia’s eyes tracked me like a cat watches a glass slide toward the edge.

When I opened the door, a man in a dark suit stepped into the foyer, leather briefcase in hand. “Good evening,” he said, with the calm of a person who has spent his life entering rooms at exactly the right moment. “I’m Mr. Carver. I represent Riverside Holdings, LLC. I have documents for the tenants of this building.”

The air changed, the way it does when equal pressure finally meets a room.

“Tenants?” Victoria laughed again, but it sounded thinner. “I manage this property.”

“Not anymore,” Mr. Carver said pleasantly. “Riverside Holdings purchased this building three years ago. I’m here on behalf of the owner.”

“That’s impossible,” Victoria said, looking to our father for confirmation she didn’t get. “I would have known.”

“You didn’t ask,” I said, stepping back into the living room, feeling at once the familiarity of hand-me-down furniture and the newness of the ground beneath it. “You were too busy telling me how to stand on my own feet.”

Mr. Carver set his briefcase on the coffee table and opened it. The scent of leather and paper, ink and inevitability, carried through the room.

He laid out the title deed, tax receipts, renovation permits, rent rolls. My name appeared in neat, legal script more than once. Madison Irving. Three years ago, with Grandma’s quiet inheritance—the thing she’d tucked into my palm with a whisper about the quiet ones being the smartest—and with every dollar I’d saved, I’d bought the building through a holding company. I’d painted trim at night, negotiated with contractors over coffee, swapped out ancient boilers for efficient ones because heat should be dependable. And I’d done it while letting Victoria believe the story that made her feel tallest.

“Ms. Irving is the sole owner of this building,” Mr. Carver said, not unkindly, just stating a fact as he slid the deed toward Victoria. “Every tenant here pays rent directly to her holding company.”

He paused the way professional people do when they’re about to say something human. “Including you,” he added.

Cousin Derek’s smirk disappeared. My mother’s knuckles whitened around her glass. My father’s fingers stopped moving.

“You’re lying,” Victoria said, but the paper in front of her made a liar of her mouth. She looked at me, and in her eyes, I saw the same expression I’d seen a hundred times, inverted—the confusion of someone who miscalculated a climb and found herself at the bottom of a staircase she didn’t see.

“You raised my rent in a building you don’t own,” I said, folding my hands and placing them on my knees so I wouldn’t clench them like I used to when she was right. “You tried to evict me from my property in front of the whole family.” I let the silence do a beat of work, then added, “That must be humiliating.”

It was. Her throat worked, but no sound came out. The room’s quiet rearranged itself, the way spaces do after you move a heavy piece of furniture and notice how the light falls differently.

“You can’t do this,” she finally whispered. “Grandma put me in charge.”

“She asked you to manage,” I said, as gently as I could manage back, “to take care of details. She asked me to listen.”

I remembered Sundays at Grandma’s kitchen table with stacks of statements and a yellow highlighter. The way she’d press a business card into my hand and say, “Not everything important is in the will.” The way she’d look over at the picture of the building on Riverside and sigh. She didn’t like fights. She liked plans.

“I’ve been in charge all along,” I said. “You just preferred a story where I wasn’t.”

Victoria’s lips trembled. “You’re cruel.”

“No,” I said, not bothering to soften the edge the sentence had earned. “I’m done being quiet so you can stay comfortable.”

Mr. Carver closed his briefcase. “That concludes my business,” he said. He shook my hand and nodded at the room before letting himself out. Aunt Patricia’s “oh my heavens” tried to fill the space he left. It didn’t.

I stood. “I’m stepping outside,” I said to no one and everyone. “I need air.”

As I reached for the doorknob, my father finally spoke my name. It was an instinctive reach, not a real invitation. I didn’t turn.

On the sidewalk, the night was cooler than it had any right to be in a city that had baked all day. I looked up at the windows of the building I owned and felt, for the first time in that living room, the truth of my body. Not small. Not shrinking. Just steady.

People think the satisfying part is the reveal, the paper on the table. That helps, sure. But the part that lives in your bones is the moment you realize you stopped needing their noise to know your worth. That’s when quiet becomes power instead of punishment.

Inside, murmurs rose and fell like the tide. Outside, the tick of Grandma’s clock couldn’t reach me. I drove home with the windows cracked and a plan that had taken root long before tonight.

Part Two

The fallout didn’t arrive like thunder. It came like breaking glass—small, sharp, everywhere.

For days after Grandma’s living room, no one called. The group text stayed blank except for a single GIF Derek sent—Michael Scott screaming “No God please no”—and then even he retreated. Silence had always been Victoria’s favorite weapon. I let it be mine.

The tenants, on the other hand, filled the quiet. Mrs. Li from 3B sent a thank-you note with a crocheted coaster. The young couple on 2A knocked to say the hallway light had finally been replaced, and hadn’t the cream paint made the whole space feel warmer? It had. I’d chosen it to match the afternoon light Grandma’s kitchen got in October.

In the office at the end of the first-floor corridor—the one Victoria used as a prop—I set a battered oak desk I’d found on Craigslist, two chairs that didn’t match but belonged to each other somehow, and a coffee machine that made the hallway smell like mornings. I put a jar of dog treats on the windowsill because dogs tell the truth.

We sent new leases—not with $6,800 rents, not with predation masquerading as market rate, but with numbers that made sense because buildings should make neighborhoods better, not bleed them. We wrote a policy about leaks that didn’t include shrugged shoulders. We fixed the boiler before first frost.

A week after the reveal, Victoria called. The number flashed across my screen like a childhood nickname you stopped answering to.

“You can’t expect me to pay rent to you,” she said after I answered. No hello.

“Expect? No,” I said. “Require? Yes.”

“You’re enjoying this,” she said, as if naming pleasure made it petty.

“I’m working,” I said. “You should try it.”

She hung up. Two hours later, my mother called.

“You’ve humiliated your sister,” she said without preamble. “Do you know what people will say?”

“They’ll say exactly what they see,” I said, unwilling to hold the picture for her anymore. “You watched her try to crush me in a room full of people and said nothing.”

“We didn’t want to make a scene,” she said, a familiar defense.

“You didn’t have to,” I said. “You just had to make a sound.”

She hung up without goodbye. I didn’t call back.

Mr. Carver—the attorney who’d lain out my papers like knives—was more talkative. “Renovation permits are approved,” he said when I stopped by his office. “And the contractor likes you.”

“I bake muffins,” I said. “You’d be surprised what they do for compliance.”

He grinned. “There’s one more thing. The bank across town is offering a favorable line if you want to look at the building on Hempstead.”

The building on Hempstead had been stubborn for a decade—bad wiring, worse management, a tenant list married to sorrow. I went to look anyway. Half the windows were open to weather. A man with a pit bull as gentle as a saint held the door for me. He’d lived there twenty-three years. “You the new owner?” he asked, cautious hope tucked in the last word.

“Thinking about it,” I said, stepping over a broken tile. “You like it here?”

“I like what it used to be,” he said. “You could sit on the steps and know everyone’s name.”

I bought Hempstead in a month with muffins and a spreadsheet. Victoria sent a message—You’re reckless with money you didn’t earn—and I laughed in a way that felt less like mean and more like free. I earned every cent of steadiness I now stood on.

Our parents broke their quiet a month later.

“We could have handled that differently,” my father said over coffee in their kitchen. He had aged in weeks. “She was wrong,” he added, as if the admission were a currency he could hand me now to cover a deficit that had accrued interest for years.

“So were you,” I said, too tired to grade the apology. “The day you don’t speak is the day you choose a side.”

He winced. “You always were dramatic.”

“You always were quiet,” I said, and we left it there because the only thing lonelier than being right in a room is being the only one willing to say so.

I saw Victoria at the mailbox in front of the building two days later. The envelope in her hand had my holding company’s name on it. She stood very straight when I approached, chin set like a verdict.

“You changed the lobby,” she said—accusation, not observation.

“I cleaned it,” I said.

“You always liked cleaning up after people,” she said, then faltered when she heard the venom in her own voice.

“You always liked letting me,” I said. “I’m done.”

She stared at the envelope as if it were on fire. “We grew up in the same house,” she said finally, voice cracking. “How did we end up… here?”

“We didn’t,” I said. “You ended up here. I built here.”

I walked away because there are conversations that pretend to care about the past but only seek to negotiate the present.

Six months in, the building’s ledger looked like a heartbeat—steady, honest, sustainable. Hempstead had a new roof. Mrs. Li’s grandson painted a mural in the stairwell—wildflowers that refused to stay in their designated plot. I cried the first time I walked past it, then laughed because no one was there to see.

Grandma’s lawyer—the one she’d kept separate from the family circus—sent a letter pressed with an old-fashioned raised seal. It contained a handwritten note she’d left to be delivered “when the quiet one needed a loud memory.”

Madison, she’d written in her looping hand. Victoria can hold a room. You can hold a building. Don’t let anyone tell you those are the same skill. Love, G.

I framed the note and hung it inside the electrical panel closet where only I would see it. It seemed right.

In spring, I threw the first tenant barbecue the building had seen since before I was born. We borrowed three grills, strung lights that made the back lot look like a photograph of joy, and let the kids chalk the whole world. Mrs. Li made dumplings. The man with the pit bull brought sixty hot dogs and two stories that made everyone cry in a good way. Someone’s uncle sang “Stand By Me” off-key while we clapped like people who mean it.

Halfway through the evening, Victoria appeared at the far end of the lot as if summoned by smoke. She had a foil-covered tray in her hands. Potato salad. It was the only recipe our mother had ever taught us both.

She stood just inside the circle of light and looked unsure for the first time in her life. She found me with her eyes and waited. I walked toward her thinking about wolves and olive branches.

“Do you want help carrying it to the table?” I asked. It was, for both of us, a treaty.

“I made your favorite,” she said instead, and then corrected herself without looking at me. “I made Grandma’s.”

We carried the tray together and set it beside the dumplings. No speech. No apology. We stood in the warmth of lights and char and summer and didn’t talk about the living room with the mantel and the lavender air. Sometimes survival is a boundary. Sometimes justice is a potato salad on a folding table.

A month after that, Victoria knocked on my office door. She looked like a woman who’d walked a long time in shoes that didn’t fit. She sat without waiting to be invited because we were sisters whether I liked it or not.

“I need advice,” she said, the words surprising both of us.

I waited.

“I don’t know how to do anything that isn’t visible,” she said, eyes fixed on the stapler on my desk, as if it held the answer. “I only learned how to hold a room. You learned how to hold… this. I don’t know how to build what doesn’t clap back at me.”

“You start with something that looks small and is everything,” I said. “You fix the boiler. You show up for the tenant meeting. You make muffins for the crew you’ll ask to come in on a Saturday. You stop giving speeches at people and start asking them for their schedule.”

She laughed once without humor. “You always were better at lists.”

“You always were better at walking into rooms,” I said. “Use it for someone else this time.”

She nodded, then surprised me. “I’m stepping away from the firm,” she said quietly. “I don’t like who I am there. I’m not sure I like who I am here.”

“You can be someone else,” I said, and this time, I meant it for both of us.

When she left, she didn’t look taller or smaller. She just looked like a person who had finally stopped performing long enough to feel weather. I felt a tenderness crack through my sternum, the kind Grandma would have told me was a good sign.

Months later, Aunt Patricia stopped me on the sidewalk and said, too loudly, “You always were the smart one,” like it had been her opinion all along. I smiled in a way that closed the conversation.

My parents continued to do what they did best—hold hands at the edge of a thing and call it stability. Our relationship found a new, awkward level. My mother showed up with a fern one morning and asked where it would get the most indirect light. I didn’t tell her I’d learned the answer years ago without her. I just pointed to the back corner of the foyer and watched her smile when the plant lived.

On the first anniversary of the night Victoria tried to triple my rent, I stood in the living room that had always felt too small for my body and watched the light move across the cheap rug someone had bought in a panic when our parents let the good one get stained. The clock on the mantel, Grandma’s brass, ticked loudly. I took it down and wound it. It had been slipping by seconds since she died as if respect for time only lived in the hand that wound it.

I set it back and felt, for the first time, the grief of the girl who didn’t get defended. I let myself cry—not loud, not performative—just enough to let the ache leave my bones. Then I wiped my face with the same care I give windows after painting the trim and went downstairs to meet the electrician because the first-floor hallway light had started to flicker again.

At the end of that day, I wrote three checks—one to the tenant fund for emergency assistance because unexpected bills should not start avalanches, one to a legal aid clinic because leases can be weapons or shelter, and one to a scholarship in Grandma’s name because the quiet ones need loud money sometimes.

I taped a copy of the building’s original permit to the back of my office door. Every morning I touched the edge as I walked out to deal with clogged drains and overdue notices and paint chips the color of cream. It felt like putting my finger on a pulse.

If you ask me now whether the silence of my parents that night still hurts more than Victoria’s words, I will tell you this: their silence built a spine in me I didn’t know I had. Her words sharpened it. My work gave it purpose.

Victoria once told a room that the only way I’d stand on my own feet was if she pushed me. She wasn’t wrong about the standing part. She just didn’t anticipate the ground I’d claim when I did.

So here is the ending you asked for: There is no dramatic reconciliation on a porch in a thunderstorm. There is a building with warm paint and a mural that insists you notice the flowers. There is a sister who is learning to hold rooms differently. There are parents who bring ferns and forget the watering can and let me show them where to put it. There is a woman at an oak desk with a jar of dog treats on the sill and a spreadsheet that balances, who knows the smell of lavender in vents and basements in spring.

There is a clock on a mantel that ticks a little too loudly in a room that is finally mine to fill with sound if I want to.

And there is this sentence—steady, deliberate, earned—that I say to myself when the old story knocks: You own more than the deed. You own the story.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

She laughed in my face, claiming i was never legally married to her son. CH2

She Laughed in My Face, Claiming I Was Never Legally Married to Her Son Part One When people talk…

Why do you hate your parents? CH2

Why Do You Hate Your Parents? My parents kicked me out for getting a job and not being able to…

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was Rich. CH2

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was…

At Brunch, My Mom Smirked “You’re Lucky We Even Include You—Pity Goes A Long Way. CH2

At Brunch, My Mom Smirked “You’re Lucky We Even Include You—Pity Goes A Long Way” Part One They chose…

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left. CH2

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left Part One In…

At Dinner, My Sister Called Me A ‘POOR TRASH WORKER’ — Then A Guest Asked, ‘WHAT’S THE OWNER DOING?’ CH2

At Dinner, My Sister Called Me A “POOR TRASH WORKER” — Then A Guest Asked, “WHAT’S THE OWNER DOING?” …

End of content

No more pages to load