The Judge Froze in Court When He Saw Me — No One Knew Who I Really Was Until…

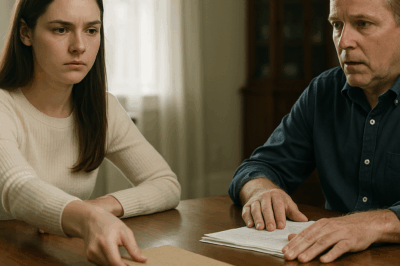

Part One

The morning I climbed the courthouse steps, fog clung to Riverton like a secret. It made the red brick façade look older, as if the building itself had been waiting for me and all the ghosts I brought with me.

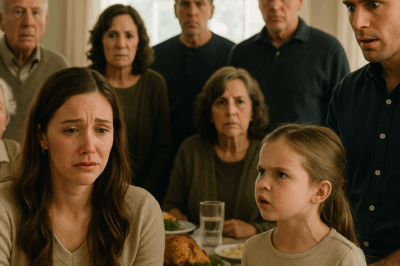

Lena and Trent were already there when I rounded the corner into Courtroom 3B—my daughter in a fitted navy dress with her hair pinned back as tight as her jaw, my son-in-law checking his reflection in the black screen of his phone. When they spotted me, Lena rolled her eyes and leaned toward him, saying something under her breath that made them both smirk. The clerk called the case and the low hum of conversations lifted, drifted, died.

That was when the judge lifted his head from the stack of motions on his desk. His eyes scanned the room, indifferent at first, and then he saw me.

He stopped. His fingers stalled mid-turn on a page. He looked as if the past had just stood up, pulled out a chair, and sat down with him.

In a voice hardly louder than the whisper of paper, he said, “It’s her.”

Silence spread like ink on cloth. A lawyer who’d been gesturing froze, his hand suspended in air. The bailiff shifted nervously. Even the old fluorescent light in the back stopped flickering for a heartbeat. Lena’s smug look wavered. Trent frowned, confusion rippling across his face.

They had no idea what those two words meant. I did.

Every morning in Riverton began the same way for me. I rose at six, filled the battered blue kettle Harold and I had bought the week we were married, and set it on the stove. While the water heated, I moved down the kitchen windowsill, checking the African violets one by one—turning a leaf here, pinching a brown edge there, talking to them in the same soft nonsense I had used when Lena was a baby. Harold had loved those violets. Tending to them kept him on this side of the silence.

It wasn’t an extraordinary life. It was a rhythm of small habits—batches of cornbread for church, hemming Mrs. Ruiz’s slacks for seven dollars and a smile, the quiet thrill of checking a list and crossing off grocery items with a pencil worn to a nub. I worked nights cleaning offices after Harold’s shift at the mill, sewed until my knuckles ached to pay for Lena’s dance lessons, and sold pies at every school fundraiser like they were tickets to her future. If anyone asked me who I was, I would have said “mother” before any other word.

That Thursday, the house smelled like rosemary and flour and the faint, clean scent that clings to old linen. I had laid out the embroidered tablecloth I finished the spring Lena turned fifteen—the one with teacups and vines along the border. It took me months to complete. My eyes went soft and blurry, and back then she had teased me about it, thumbing the uneven stitches while she ate straight from the mixing bowl, laughing with sugar on her lips.

I had made Harold’s favorite chicken and dumplings and arranged peonies in a cracked vase. I had even changed the lightbulb in the hall so the mirror would flatter, the way Harriet from the beauty parlor taught me. I wanted the house to say what my tongue couldn’t: You are still loved here. You are still wanted.

When they arrived, Trent walked into the living room and sank into Harold’s chair, as if it had been waiting for him all along. He didn’t ask. He just pressed the remote, flipped to a sports channel, and made himself comfortable. The chair groaned like a person who knows better but won’t speak up. Lena stood there smoothing her green dress, the one I’d bought her last Christmas, with a mouth as cold as rain.

“Mom, we need to talk,” she said. Her voice was clipped, a blade wrapped in silk. “This house is too big for you. You can’t keep up with it. We’ve found a place—a lovely community. They have activities and a bus so you won’t have to drive. It’s best for everyone.”

I set the ladle down and gripped the edge of the counter to keep my hands from shaking. “This is Harold’s house,” I said. “He died holding my hand in that bedroom. That stoop held Lena’s first steps. Some things you don’t move just because—because you feel crowded.”

“Memories are in hearts, not on walls,” Lena replied, all philosophy and none of the dirt under the nails. She said it the way people say the Pledge when their mind is on traffic.

Three days later, Trent showed up with a stranger in a gray suit who introduced himself as a real estate appraiser. He walked through the rooms with a tape measure and a clipboard and the detached attention of a man inventorying bones.

“The pipes are outdated,” he said, peering beneath the sink. “Tile’s old. This kitchen would need a gut reno.” He pronounced reno like a luxury.

I stood in the doorway and looked at the tile he had dismissed, remembering how Harold had lined them up on the counter in a neat row and turned to me like a boy at a fair, grinning. “We’ll be eating on this when we’re eighty, Nor,” he’d said, touching one with a reverent finger. “We’ll set coffee cups here. We’ll fight and we’ll make up and this will be under us the whole time.” He had sweat running down his temples and the radio on low, and he hummed along without noticing he was off-key.

The appraiser scratched something on his clipboard and moved on to our bedroom.

A week later, they came with a lawyer. Not the family lawyer I knew, but a young man with a square jaw and a briefcase that shouted billable hours. He spread documents across my dining room table, pushing aside the peonies without looking at them. The papers were a forest of small print and rugged words—transfer of ownership, durable power of attorney, permanent, irrevocable.

“Mrs. Whitaker,” he said, with rehearsed politeness. “Once you sign, your daughter will be in safe hands to manage your affairs. The retirement community is lovely. The sooner we finalize, the smoother your transition will be.”

I slid page after page toward me and felt my breath shorten. It wasn’t a sale. It wasn’t even consent. It was a giving over. The legal language coiled around my wrist and squeezed.

“I’m not signing,” I said quietly.

Trent’s mask slipped. “You’re not in a position to decide anything,” he snapped, leaning over the table so close I could count the pores on his nose. “Lena is your heir. She knows what’s best for you.”

“If you don’t cooperate,” the lawyer added softly, as if he cared, “we may have to explore competency proceedings.”

That night I sat in Harold’s armchair and stared at the doorframe he had nailed a growth chart into with a butter knife, when we still measured time in inches and bangs and pencil lines. Sleep avoided me. Doubt didn’t. Maybe I was too tired. Maybe I had been selfish without knowing, insisting on loving a house when I should be loving people faster.

In the heavy quiet, I talked to Harold like a woman who never learned how to stop. “I don’t know what to do,” I said into the room. The clock ticked its patient little ticks. No thunderclap of wisdom came. Just the ordinary sound of time moving whether I liked it or not.

In the afternoon, while dusting shelves where dust keeps coming back like a neighbor with too much time, I slid open Harold’s desk drawer. It was full of the usual: paid bills, rubber bands that had long since given up, a few screws in a matchbox labeled “bedroom lamp?” in his tidy printing. Beneath those, something new: a slim folder bound with a tiny lock.

I hadn’t seen it before. I hadn’t seen a key, either. I went through every drawer in that desk, then the coat closet, then the junk bowl by the phone, then Harold’s books—spines that cracked, pages that fell open to recipes he had marked with stars. Tucked into the back of a book on mutual funds I’d never seen him finish was a small brass key.

My hands shook when the lock gave. The folder creaked open and exhaled paper. Inside: statements, deeds, contracts, a neat list of accounts with balances that made me sit down. Harold, who had hummed along off-key, had also been humming along quietly at something else.

For decades he had taken whatever was left—tips from odd jobs, bonuses, overtime—and tucked it away. While I clipped coupons and rolled quarters for gas, he was buying a small duplex on Elm Street in 1989 at a price that looked like a misprint, putting a hundred dollars a month into a fledgling company called Cascade Logistics, buying a triangle of scrubby land beyond the river that was now surrounded by houses.

But it wasn’t the numbers that made me press a hand to my chest. It was the address on one deed in particular: 216 Carlton Avenue.

Lena and Trent’s building.

I read the line again. Owner of Record: Harold J. Whitaker, now transferrable to surviving spouse per Will dated April 12. The rent stub copies in the folder—every month for two years—came from a management company I’d never heard of. All those checks had been walking right into an account with my name on it. I had never looked. Harold had always been the one to open the mail with numbers on it, and after he passed, I paid what came and saved what I could. I’d assumed their “rent” was going to a mortgage. It had been going to me.

At the bottom of the folder was an envelope addressed in Harold’s hand: For Nora.

I unfolded the letter with the care of a woman pulling a splinter she knows will hurt.

My dearest Nora, he’d written, his blocky letters falling downhill the way they always had. If you are reading this, I am not there to make coffee or curse at the paper. Forgive me for keeping this quiet, but you love peace more than you love numbers. I wanted this to be a gift and not a fight. You worked harder than anyone and spent more nights with bleach on your fingers than I will ever forgive myself for. I want you to live soft at the end, not scared.

One more thing. I never trusted that boy. There’s ambition without a spine in him. I worried he’d make our girl sharp in the wrong places. So I wrote this so you would hold the handle. If she chooses love and respect, she will stand beside you in this. If she lets anyone put a boot on your neck, you will have the power to get up and lock the door. Use it wisely. Not to hurt. To teach.

By dawn, I had made my decision. I watered the violets. I washed my face. I taped the tiny lock back onto the folder and set it on the desk like an answer.

When Lena and Trent arrived with movers that morning, boxing tape at their belts like cowboys, they found me in Harold’s chair with a cup of tea, my feet planted firm on the floor.

“Mom, what are you doing?” Lena asked, irritation peeking out from behind concern. She looked tired—new tired, the kind of tired that comes from secrets that aren’t yours pressing on your ribs.

“I’m not leaving,” I said. “But you are.”

Trent laughed the laugh of a man who had not yet learned my name for steel. “You don’t have a say, Mrs. Whitaker. The papers are ready. So are the boys.” He jerked his head toward the hallway where the movers shifted like men standing in a room with lightning.

“You’re right,” I said. “I don’t have a choice. But it turns out you don’t either.”

I walked to Harold’s desk. My knees complained. I opened the folder and took out one deed. “Did you know,” I asked conversationally, as if we were neighbors at a bake sale, “that the apartment you’ve been living in for three years belongs to me?”

Lena blinked. “We pay rent.”

“To a management company,” I said. “That transfers it to me.” I tapped the deed. “Check the county records if you like. They’ve never cared who I was. They just care who signs.”

Trent’s mouth opened and then closed. His hand went to his hair, pushing it back and leaving a ridge. “This—this is a trick. A fake. You’re bluffing.”

“You can ask Camille,” I said, dialing my attorney on the old landline because calls like that should have weight to them. “She’s very good with men who stop believing in paper the moment paper stops believing in them.”

Camille confirmed the obvious on speaker. The manager’s cheeks flushed three shades of red. The movers looked like men who would rather be anywhere else. Trent’s face went flat, the way a pond does just before it freezes.

“You can’t kick us out,” Lena said, panic shockingly human behind the lawyer’s daughter composure. “I’m—I’m pregnant.”

Words I had imagined for years fell into the room like hailstones. For a moment, joy rose up so strong that I had to grip the back of Harold’s chair to keep from moving toward her. Then I remembered the boxes. The appraiser’s clipboard. The way she had looked at our walls and seen only empty.

“Congratulations,” I said softly. “But my grandchild won’t be raised to believe taking what isn’t yours is just good planning.”

Lena’s eyes filled. She turned to Trent with something like a question forming in her mouth. He jerked his arm away from her touch.

“You’re weak if you give in,” he said, loud enough for the men in the hallway to hear.

Something shifted in my daughter’s face. Not a transformation. A remembering. People think noticing is a small skill. It is not. It is the beginning of every rescue.

“Mom,” she whispered, voice shaking. “I’m sorry. I don’t—I don’t know how to fix this.”

“You don’t fix it,” I said. “You stop breaking it.”

Two weeks later, he showed up at my building again, red-eyed and reeking of bourbon. He jabbed a finger at me in the lobby as if that would hold me to the floor. “You give me back my wife right now,” he said, loud enough for the mailboxes to hear. “Or I’ll call the police and tell them you’re holding her prisoner.”

“She’s upstairs in her mother’s house,” I said. “That’s not a jail. It’s the opposite.”

“This isn’t your building,” he said, and I swore he believed it. Some men assume reality is the story that scares them least.

I held the phone up again so Camille could do what she does best: turn men into witnesses against themselves.

The suit came next. Of course it did. He hired a lawyer who thought adjectives could replace evidence. They painted me as a bitter woman clinging to walls and baseboards out of spite, a cunning matriarch controlling her daughter with money and guilt. He threatened custody. He used words like alienation and elderly and manipulation because he had seen them work on juries on television.

Camille assembled what the truth looks like on paper: texts with threats spelled out in the urgency of drunk thumbs; voicemails that started suave and ended with rage; sworn statements from neighbors who heard him call my daughter names the English language should be ashamed to host; financial records that looked like a cautionary tale; copies of the competency papers they had planned to file. Piece by piece, the story shifted under its own weight.

“Answer directly,” Camille said, the night before the hearing. “No embroidery. No philosophy. The truth doesn’t need lace.”

Lena practiced saying hard sentences out loud at my little table, the same table she did her first-grade spelling at, the same table where one summer Harold helped her color in a map of the United States and made up a song for the capitals. I thought I was protecting my husband when I was just protecting his pride. I was wrong. I chose him over the woman who washed my hair over a kitchen sink and worked nights so I could have dance shoes.

She cried. She kept going. I folded dish towels until they were squares of breath.

We sat on the hard benches the morning of the hearing, hands folded in our laps the way our Sunday school teacher taught us: left over right, thumb over thumb, quiet enough to hear the ceiling buzz.

Trent swaggered in with an attorney at his shoulder, the smell of smug hitting the room like aftershave. He swept his gaze over the benches, lingering on me the way a hawk lingers over a mouse it hasn’t finished eating yet.

The judge slipped onto the bench and the hum of whispering died. He looked down at the docket and then up at the people who had wandered in to watch other people’s trouble.

His eyes found mine.

Something in his face gave way. Not power. Awareness. He took off his glasses and polished the lenses with the hem of his robe, the way people do when they need three extra seconds before they admit they remember you.

“Mrs. Whitaker,” he said, voice softened by surprise. “Do you remember me? Thirty years ago—family court—Harland’s office. You were the secretary who worked late. You helped an intern close his first file. I was that fool.”

Memory arrived like a visitor I’d hoped would come. Under the gray and the gravity, I saw him—the boy with the too-large suit and the hands that shook when he stamped the wrong date, the one who once knocked over a pencil cup and went scarlet, the one I had made tea for because he looked like he needed someone to see him as human and not a machine that made mistakes.

“Marcus,” I said, because that was his name and memory is a kind of debt I like to pay. “Of course I remember.”

The room gathered itself in tighter. Trent’s lawyer popped to his feet with an indignant objection, words like bias and conflict of interest spraying from his mouth like foam.

“There is no conflict here,” Judge Ellery said, the softness gone. “There is only justice. And the evidence.”

He listened. He watched. He interrupted elegantly when Trent’s lawyer tried to turn adjectives into facts. He asked Lena to repeat certain sentences, not to hurt her but to let the record hear her clearly.

When he read his ruling, he did not pause for oxygen. He denied every one of Trent’s claims without ceremony. He named what had happened—intimidation, coercion, emotional abuse—and ordered the exact things that men like Trent pray judges don’t order: a restraining order that bites, a review of parental fitness that doesn’t use words like boys will be boys, court costs that sting, damages that meant something even to a man who thinks paying is humiliation.

As the gavel came down, I looked at Lena. She looked like a woman waking up after a fever—sweaty, shaky, but here.

We walked out of the courthouse like people who had just been released from a story that didn’t belong to them. On the steps, she grabbed my hand like a child, and for the first time since she was ten and fell off her bike on Maple Street, I said, “You’re free.”

She nodded, tears on her cheeks, and whispered, “So are you.”

Freedom didn’t look like a parade. It looked like laundry folded without bitterness. It looked like Lena taking a deep breath before answering Trent’s last late-night call and then blocking his number, not because she was cruel but because she had finally remembered she wasn’t a door.

When she moved back into the house, the air between us was fragile in the way thin glass is—breakable, but worth saving. We spoke carefully around old wounds and only about the present for a while: grocery lists, appointment times, whether the church rummage sale still took electronics. I showed her where Harold had kept the screwdriver, and she showed me how to scan a check with my phone. She washed her dishes. She watered the violets without being asked. She took out the trash on Thursday nights, the way a person who wants to rise in someone’s esteem starts with the simplest verbs.

“Words are beginnings,” I had told her in the kitchen the night she came home with a bag and a face like a bruise. “But actions are the way.”

She nodded then. She showed me now.

When her belly rounded, the house grew a silence that didn’t hurt. There were evenings when we sat on the front steps and watched the neighborhood time itself. The teenagers on the corner practiced their skateboard tricks. Mrs. Ruiz left for the night shift with a thermos and a wave. Cicadas warmed their voices and sang until the dark said stop. We didn’t talk about the trial. We didn’t talk about the letter. We sharpened carrots with a little peeler and made soup.

The day Isla was born—dark hair, mouth like she meant business—the world moved to make room. I held her under the hospital’s baked air and said, “You will not grow up believing love comes with a signature line.” Lena laughed and cried at the same time and said, “Deal.”

Harold had wanted his money to do more than sit and grow numbers. “It’s all paper until it feeds somebody,” he used to say, standing in line at the grocery store with three coupons and a sermon about waste that made the cashier smile.

With Camille’s help, I took some of what he left me and hammered it into walls. We called it Second Porch because some porches collapse under time and some are stolen by people who call theft responsibility. We rented a blue house and a gray one and a squat building that had been a dentist’s office in 1972. We filled them with beds and rocking chairs and a kitchen table at each, and we opened the doors to older women who had been told their usefulness expired the year their knees started hurting.

In the first year, fifteen women found their way to our porch. A woman whose son sold her car while she was in the hospital recovering from surgery; a retired teacher whose daughter moved her into a storage unit when she asked why the mortgage had missed two payments; a woman with hands like mine whose husband of forty years died and left the account to a son who said “we’ll see.” We gave them keys. We gave them a schedule that respected sleep. We gave them coffee and dignity and a way to remember their names without adding the word burden behind it.

Letters began to arrive. Handwriting shaky and fragrant with the smell of drawers. “You gave me back my name,” one read. Another: “When I said I had nowhere to go, you said ‘here,’ and that word saved me.” I tacked those letters to a cork board in the office so I could touch them when I needed to remember why you bother knowing where the screwdriver is.

One afternoon, a thick envelope came with embossed return address: Riverton Retired Judges Association. Inside, an invitation to a banquet honoring “citizens who turned suffering into service.” Judge Ellery’s note was clipped to it: Nora, you taught me stamps were not the same thing as judgment. I’m just paying it forward. He wrote like a man who still stamps things too hard.

We went, Lena and I—me in a dress I bought at a thrift store and altered with darting because new fabric doesn’t make the woman, just the price tag. Marcus stood at the podium with hair thinner than it should have been and a smile that could still redeem a torn out-of-order sign. He told a story about a secretary softening disaster with tea and courage, and I realized I had been someone’s Section Four a lifetime before I ever wrote mine.

Five years after the morning fog thickened at the courthouse, the garden behind my house was loud with spring. Isla ran barefoot across the grass chasing a butterfly and scolding it for not taking turns. Lena stood on the steps with flour on her hands, calling out instructions to me that contradicted the recipe in a way that would’ve made Harold grin. I sat at the picnic table and cut up strawberries for a pie I’d already made in my head a dozen times.

An invitation to the opening of our third Second Porch home sat under a magnet on the fridge. Three. If you’d told me that when I was sitting under a cheap blanket in Harold’s chair telling dead air I didn’t know how to go on, I would’ve asked you to leave because I didn’t have room for miracles on that couch.

Judge Ellery came by that week with his wife and a bouquet of hydrangeas the size of a baby’s head. He stood in the doorway and looked around like he’d been here before in a story someone told him. “You turned a folder into a foundation,” he said, shaking his head. “I retired men think that’s about as good as a bench ever gets.” He presented me with a plaque I didn’t need and a hug I didn’t expect.

Later, after the hydrangeas found water and Isla fell asleep in a heap of books she’d used as stepping stones, Lena and I sat on the porch with two cups of tea and the kind of quiet that makes words unnecessary.

“I used to think strength was loud,” she said at last. “You taught me it can be a woman standing up slowly and saying no once, and then again, and then again.”

“Strength is also folding laundry,” I said. “Don’t forget that part.”

We laughed. We sat. We planned for the day Isla would be old enough to match socks.

The morning I walked into Courtroom 3B and the judge’s face changed, I had no idea the sentence waiting for me had started thirty years earlier with a shy intern and a secretary who stayed late. I had no idea that saying no to a man in my dining room would turn into a set of keys for strangers who would become family. I didn’t know that a piece of paper locked in a little folder with a brass key would hold the shape of the rest of my life.

I know now.

Sometimes the victory isn’t a man pounding a table until the plates rattle. It’s a woman watering violets and quietly saying, not this time. It’s a judge remembering who made him tea when he thought he would drown. It’s a daughter with flour on her hands who learned to say I was wrong and then to mean it. It’s a child named Isla running across a lawn with her arms flung wide, growing up in a world where walls hold stories and porches hold second chances.

It’s a house with old tile and a table with a scar where someone once slammed a spoon. It’s a file folder and a letter and a plan and a garden and a foundation and a courtroom where time looked up, saw kindness, and stopped long enough to let it in.

The Judge Froze in Court When He Saw Me — No One Knew Who I Really Was Until…

Part Two

Spring let go of Riverton (reluctantly, as always), and the heat set to work on the sidewalks. The violets put up a brave fight on my windowsill. Lena insisted on helping me rotate them so the leaves didn’t lean toward the sun like desperate children at a candy store window. Isla learned to say leaf and soft in the same week and used both indiscriminately, patting everything with reverence—books, dogs, the judge’s plaque the retired association sent me, even the cold glass of the front door.

We rebuilt like people who’ve already learned which boards hold and which splinter. Lena’s apologies stopped being nouns and turned into verbs. She kept her appointments. She kept her temper. She kept the receipts. She went back to school with a diaper bag slung over one shoulder and a backpack over the other and came home and boiled pasta and bathed Isla and did not complain out loud even once. She started helping with Second Porch’s books at night—clean columns, quiet totals—and when she caught me making a dime go where it wouldn’t fit, she simply nudged the calculator toward me and said, “Try again, Mom.”

Word about Second Porch traveled the way truth often does—by casseroles and church bulletins and the good kind of gossip. We signed the lease on a third house that used to be a dentist’s office and still smelled faintly of clove oil; then a fourth—a sagging, shuttered motel off Route 17 that other people passed and other people clucked their tongues over and then forgot. We didn’t forget. We measured the rooms with borrowed tape measures. We pulled the carpet staples with pliers. We painted the doors red so the women could find them.

It was almost enough to make me forget about men who think trouble is a pet that will always come when they whistle.

The letter arrived in July.

It was expensive paper with an embossed crest and a tone that believed itself benevolent. Crestline Partners had bought the patchwork of lots between our neighborhood and the old river path—lots that had once belonged to families I could name with my eyes closed; lots the bank had softened and then swallowed after the flood in ’98; lots Harold had once wanted to buy but wouldn’t touch with money that should have been for heat.

Dear Ms. Whitaker, it began. As you are undoubtedly aware, Riverton is evolving. Our firm intends to bring jobs and revitalization to your corridor by constructing a mixed-use development incorporating green space, retail, and transit. We will need to acquire certain parcels, including yours, to complete a connector road. We’re eager to offer you above-market value to ease your transition.

The map attached had a neat gray line drawn straight through our kitchen.

I ran my finger along the route, past the violets, through the space where Harold’s humming still hovers. I took a breath that tasted like old pennies and called Camille.

“They’ll call it progress,” she said, already pulling down a binder. “We’ll call it what it is: lazy engineering and opportunism with a garden. Don’t sign a thing.”

They didn’t wait for our answer. The next week the paper ran a rendering: sunny families strolling with designer strollers, trees in symmetrical planters, a store that sells hats nobody needs. The article quotes were full of words like revitalize and activate. There was also a quote from a consultant Crestline had hired to help “navigate neighborhood relationships.” His name sat there in black print as if the alphabet hadn’t grown sick of holding it: Trent Maddox.

“If I were a man given to drama,” Camille said dryly, “this is where I’d cue the organ.”

We laughed because we could. Then we went to work.

I pulled out the folder with the little brass lock again and laid its contents on the table like a tarot. The deeds, the rent stubs, the letter. I went through each paper slowly, the way I’ve always picked pecans—one by one, careful not to crack what mattered. At the bottom, taped to the inside flap, was a slip I hadn’t noticed before—a copy of a filing from 2001 recording a conservation covenant Harold had placed on a swath of the lowland behind our street.

Riparian corridor preservation, no paved road shall cut, no fill shall be placed that impedes floodplain functionality. Harold had known numbers and he’d known water, but most of all he’d known how to think farther down the road than men with rolled-up plans and a sales pitch. He’d also tucked a second letter to me in that flap.

Nor, he’d written. If anyone tries to turn that mud behind us into money, remember who the river answers to. Not City Hall. Not some firm in a glass box. Use the covenant. Call it a promise, not a weapon. That way, if you win, you’ll still like yourself in the morning.

The city held a “Community Visioning Session” in the high school gym, which is what towns call it when they want to measure the temperature of a room and hope nobody notices them adjusting the thermostat. Crestline set up trifold boards with glossy prints of smiling people. There were bowls of peppermints. There were little stickers for citizens to put on pictures of things they liked—Farmers Market, Public Art, Dog Park. There wasn’t a picture of my kitchen.

Trent hovered near the boards like a man showing off a new sport coat. He had mastered contrition for the camera. His smile was the kind that squeezes someone else’s apology out of them. He did not look at me.

Lena did not look away. When it was our turn at the microphone, she stood and adjusted the sleeve of her sweater and my chest ached with the sight of her finding herself twice in one life.

“My name is Lena Maddox,” she said. Then she shook her head, corrected herself without flinching. “Whitaker. I live on Carlton with my mother and my daughter. I used to think words like ‘revitalize’ meant clean parks and safe sidewalks. But it turns out sometimes they mean ‘move the people who were here so the people who can pay more don’t have to look at what they’re replacing.’ We’re not opposed to change. We’re opposed to erasing.”

A murmur ran through the gym like a wind under a door.

Trent stepped forward, all practiced patience. “With respect,” he said—men like him always lead certain sentences with those two words—“we’ve conducted thorough impact studies. The connector road will improve emergency response times and bring tax revenue.”

He nodded at the pastor of a church that had recently replaced its roof with a donation from someone whose name hath sounded suspiciously like a development firm.

I took my turn. I did not raise my voice. I set the covenant copy on the table where the city planning director could see it.

“Dear,” I said gently, “men can draw all the lines they like on a map. The river and the deed draw their own. This land is conserved. It is documented. It is recorded. And I don’t need to be tall to stand on it.”

The planning director read the document, his eyes widening the way a person’s eyes do when their shoes are not where they remembered leaving them. He coughed into his hand and said something about “needing to review easement conflicts.” Crestline’s public relations woman did a quick calculation in her head and tried to smile past it. Trent’s jaw tightened, the way a door does when the frame swells in the heat.

They pivoted to attacking Second Porch. A letter went around with bullet points about code compliance and neighborhood character. Someone started a rumor that our houses brought crime, as if the only crimes that count are ones committed by poor people. A man wrote that we were “attracting dependency,” as if anyone had ever voluntarily chosen to need help at sixty-eight.

We invited him to the porch. We gave him coffee. We introduced him to Bernice, who taught school for thirty years and shows up every Tuesday with a bag of lemons for the lemon bars the women like; and to Althea, whose son sold her car while she was in rehab and who now runs the check-in desk for our visiting nurses; and to Marisol, who hums when she folds laundry and keeps everyone’s blood pressure pills in order like it’s a kind of prayer.

He wrote a second letter to the editor. It was short and said, “I was wrong.” The paper ran it in small type. I clipped it anyway and tacked it to the cork board under the thank-you notes.

At the zoning hearing, Crestline came with five men in matching ties and a PowerPoint that dimmed the room to make their points look brighter. They lined up words like “activated frontage” and “mixed-income units,” which everyone knows is a way to say not enough. They tried to make the connector road look like a compromise by adding bike lanes. They put a fake tree on the map.

Camille stood with a manila folder and the kind of posture that makes people who lie sit up straighter. She placed the covenant on the lectern and spoke into the microphone like it was a friend who had been waiting for her.

“This riparian corridor is not a suggestion,” she said. “It is an enforceable covenant recorded in 2001. Any road cut through this will violate state law and common sense. Furthermore, the developer’s alternate “S-curve” route would require taking homes—some of which, I must note, provide shelter through a nonprofit whose waiting list currently exceeds one hundred names.”

She did not call Second Porch cute. She did not apologize for the women sleeping under its roof. She let the covenant and the letters and the bodies in the room do what paper alone cannot.

An old man I recognized from the hardware store stepped up to the microphone next. “My name’s Henry,” he said. “This town is in my lungs and my nails. That mud took my father’s boots in ’79, and we dug him out. The river goes where it goes. I ain’t arguing with it, and neither should you.”

The board grumbled in their municipal way. The chair cleared his throat and smiled at us in the way men smile when they are already calculating how much lunch will cost when they’re done pretending. Then he saw the judge in the back row. Judge Ellery had slipped in and sat quietly with his hands on his knees like a churchboy who meant it. He didn’t wave. He didn’t intervene. He just made the room honest by occupying it. Some people carry the smell of oath with them.

Crestline asked for a continuance. They got it. They hired a hydrologist with graphs about floodplain mitigation. They put out a mailer claiming they’d add “affordable artist lofts,” as if rent were a paint medium.

While they scrambled, we worked. We found a land trust three counties over that had been looking for anchor projects. We proposed an easement expansion along the river—turning the line on Harold’s covenant into a thicker marker on the map. We offered to steward it through Second Porch, with our women tending native plants in exchange for stipends. We organized a cleanup day and invited everyone, including Crestline. (They sent a young associate in expensive boots who got stuck in a rut deeper than his doctrine.)

At the second hearing, the board members swapped glances that had the weight of risk in them. The hydrologist admitted that cutting through the corridor would require “major engineered interventions.” “Another flood waiting to happen,” Mrs. Ruiz murmured behind me. The planning director, to his credit, didn’t try to hide. He read the covenant out loud. He checked the date twice. He looked up at me afterward as if Harold might be sitting next to me and he wanted to say sorry to both of us.

“We cannot approve a plan that violates a recorded conservation covenant,” he said into the mic. “The applicant is encouraged to re-design within constraints or pursue an alternate site.”

Crestline’s attorney objected in a way that meant he knew he’d already lost. Trent stood up, his hand half-raised, still forgetting where he was in a room that didn’t ask anything of him. The chair recognized him out of habit.

“My name is Trent Maddox,” he said. He pitched his voice to the tone men use when they want you to remember they wear ties. “We all want what’s best for Riverton. Sometimes that requires difficult decisions. We can’t let emotion override progress.”

Lena rose before I could. She walked to the microphone like it owed her nothing and she owed it honesty.

“My name is Lena Whitaker,” she said. “Progress isn’t paving a road through a woman’s kitchen because a man thinks his map is more real than her breakfast. It isn’t calling code on porches that saved my neighbors when nobody else would answer the door. It isn’t asking a river to behave because it inconveniences you. We are not against change. We’re against pretending people are furniture.”

There was a ripple then—not applause, not quite. A collective exhale that said thank you without making a sound. Trent’s face went pale, the color of paper before ink. He sat down because there was nowhere left to stand.

The board voted. Three to one against the road. The one in favor was the man who always votes in favor of something because his body doesn’t work right if he leaves without saying yes. Crestline’s spokesperson issued a statement about “exploring alternative partnerships.” Their next mailer featured a project on the other side of the highway where the river does not care to talk to them.

On the walk back to the car, Lena took my arm not because I was unsteady but because we both liked the way our shadows looked that way—one taller, one shorter, strings of a kite that refused to come down.

“I’m sorry,” she said again, though that wasn’t the day for it. “I keep finding new corners to sweep. I don’t think I’ll ever be done.”

“Good,” I said. “It’s a big house.”

A year later, the motel on Route 17 didn’t smell like clove oil anymore. It smelled like lemon cleaner and fresh sheets and a little like the stew Bernice made on Tuesday nights. We painted the doors blue this time. Isla learned to count by pointing at them.

We held an open house to thank the people whose hands had held boards and checks and petitions. We strung lights in zigzags across the parking lot and borrowed a speaker from the church youth group. Women who hadn’t danced in fifteen years swung each other around under the bulbs. The judge came and wore a tie that had a stain on it near the third button. He didn’t care. He held coffee like it had forgiven him for every over-brewed cup he’d ever made.

Crestline sent a bouquet. I put it on the welcome table between a stack of flyers and a bowl of peppermints and took a picture because you should always keep proof of the day your enemy remembered the address of grace.

The house on Carlton stayed standing. The carpet was still ugly. The tiles were still Harold’s. The violets leaned toward the sun and back, the way patient things do. On Sunday afternoons Lena made biscuits from the recipe my mama had given me, adding too much salt the first time and not enough the second and just the right amount when she stopped measuring and started listening.

On one of those Sundays, she brought out a small box and sat it on the table.

“I’ve been saving,” she said, and I smiled because saving is a word that sounds like a future. “I want to buy in. Not to take. To carry. I want Second Porch to be ours, not just yours.”

I opened the box. Inside was not money. It was a small brass key on a ribbon, polished where fingers had held it.

“You gave me your name back,” she said. “Let me hold the lock sometimes.”

I closed my hand around the key. It was warm from her palm. It weighed almost nothing and everything.

That evening, after dinner, Isla and I watered the violets together. She held the little tin measuring cup with careful seriousness, tongue poking out a little at the corner of her mouth, the way her grandfather had when he tiled the kitchen.

“What’s that called?” she asked, patting a leaf.

“Violet,” I said.

She smiled like I had given her a sticker for saying it right. “Soft,” she added, practical and holy.

We sat on the porch as the light thinned. The neighborhood made its comfortable noises. Someone hammered a nail three doors down with conviction. A radio played a song I knew all the words to and none of the notes. The porch smelled like lemon cleaner and violets and hot concrete and something I still can’t name. Maybe victory. Maybe peace.

“You were right,” Lena said into the good quiet. “Kindness circles back.”

I considered the judge’s face the morning he’d said it’s her, the hydrangeas, the land trust’s check written with a pen that didn’t tremble, the way Trent’s voice had finally run out of consonants. I considered Harold’s letter, the covenant, the women who wrote to say I am not a burden, the way a young mother who once couldn’t look anyone in the eye now coordinated meal trains like an air traffic controller.

“It does,” I said. “Not quickly. Not to the impatient. But it always knows the address.”

We stayed on the porch until the mosquitoes told us the story was over for the night. I locked the door with the little brass key and set it back in the drawer where it lives with stamps and rubber bands and the matchbox that still says “bedroom lamp?” in Harold’s hand.

Sometimes I catch myself reaching up to touch the place on the wall where Lena’s head hit the growth chart. She’s taller than me now, and better where I hoped, and forgiven where I needed. I am not a woman who wins wars with shouting. I am a woman who survives them with paper and patience and violets and the nerve to say no.

The judge may have frozen the day he saw me in his courtroom, but the truth never did. It kept walking, quiet and sure, right up to our porch, took a seat, and stayed.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money’

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money,’ Brian Kilmeade passionately defended Erika Kirk on…

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent. CH2

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent Part One The rosemary lamb went…

BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions in his final statement and unexplained evidence have shocked the public: Is Robinson blaming someone else?….read more below

💥 BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions…

“I Stared At The Photo—My Son Did This?” — A Sheriff’s Father Breaks His Silence On Utah’s ALLEGED KILLER

At a $600,000 family home in Washington, Utah, a veteran lawman dialed the number no parent imagines: he turned in…

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire : Ava Raine, the daughter of Hollywood legend Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, has ignited one…

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale. CH2

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load