The Bride Slapped a Server at Her Own Wedding, Not Knowing It Was Actually Her Mother-in-Law

Part I — Falling Stars and Shattered Glass

The wedding hall shimmered beneath chandeliers that looked like falling stars, each crystal a captured tear of light. Seattle’s gray had peeled back for the day, leaving a shy sun that slipped through stained-glass windows and embroidered the marble with color. Photographers flitted like dragonflies; a pair of columned doors yawned, and the aisle unfurled—long, perfect, a ribbon of white cutting through bouquets of cream roses and eucalyptus.

Sabrina Collins drank it in as if she’d designed the sky herself. Perfection encircled her: the couture gown heavy with hand-beaded frost, the train that lay behind her like a calm sea, the veil like a suggestion of snow. People in town had been talking about this wedding for months—the designer bride, the tech-genius groom, the vendors whose names sounded like promises. This was the story the city liked best: two meteors colliding in full view.

Near the buffet, a woman in a simple black service dress balanced a silver tray of champagne flutes. She was small, the bones of her wrists like fine branches, her hair pulled into a loose bun that couldn’t decide whether to behave. She had been there since dawn—steadying candles, straightening place cards, carrying things no one would ever notice—because she couldn’t sit still when the day belonged to her son. Moses basket and midnight fevers, scraped knees and scholarship letters, his first suit that didn’t fit until she hemmed it in the kitchen—every version of him walked beside her as she moved.

Her heel caught. Just a slip—the kind that happens when a room has a thousand eyes. The tray tilted, a soft gasp gathered like fog, and a crescent of champagne leapt, flared in the light, and kissed the silk of Sabrina’s dress.

Silence followed, the kind that edits the air.

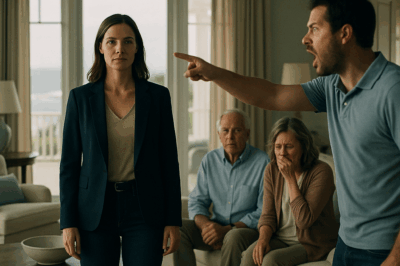

Sabrina turned, mouth an open o of outrage. Her hand flew, a white bird that didn’t hesitate. The slap cracked and ran up the ribbed columns and into the vaulted ceiling. The tray clattered; crystal exploded into small stars and skittered across marble, a constellation collapsing at the feet of the woman on her knees.

“You ruined my dress!” Sabrina’s voice found the room’s corners and tore them. “Do you have any idea how expensive this is? Get out. Before I have security drag you out.”

The elderly woman blinked, hand hovering at the red blooming across her cheek. “I’m sorry, ma’am,” she whispered. “I only wanted to help.” She reached for the shards with shaking fingers.

No one moved. Not the string quartet whose bows hung like punctuation. Not the bridesmaids frozen in their soft-petal gowns. Not the photographers whose lenses had meant to capture grace and now captured something else.

Footsteps echoed in the doorway, measured and unhurried—someone arriving late to a moment that would not forgive it. The groom, in white tuxedo and undone calm, smiled at the hush and then saw what quiet had made. His mother, kneeling. The bride, trembling with anger. The mark on a face he had kissed goodbye a thousand times.

The smile vanished.

For ten small seconds, the world measured itself around a single truth: a bride had slapped a woman she assumed was a server. The server was not a server. She was Aaron Fields’s mother.

Sabrina’s eyes darted to the stain on her hem, then to the faces gathering in a half-circle of witness, then back to the woman on the floor. “Aaron,” she started, too quickly. “She stepped into me—she—she spilled—my gown—this whole thing—”

Aaron’s gaze never left his mother’s cheek. When he spoke, the words were even, the way steel can be even. “You hit her.”

“I thought she was staff,” Sabrina said, a small laugh popping like a bubble and dying in the air. “She shouldn’t have been near me. She’s in the way.”

“That woman,” he said, pointing at the trembling hands gathering pieces of crystal, “is my mother.”

The sentence sliced the room. A bridesmaid sobbed once and choked it back. Somewhere, a camera clicked, apology in its shutter. An aunt in a hat too large whispered a prayer she’d forgotten the words to. Sabrina’s face drained of its careful color. Her hand trembled, the same hand that had flown so readily a moment before.

“I didn’t know,” she whispered, and how small knowledge sounded now. “Aaron, I swear—I didn’t know.”

“You didn’t know,” he said, his voice the quiet between those falling stars, “because you never cared to.”

He knelt. “Mom,” he said, so softly it was almost childhood. “Are you hurt?”

“I’m all right, son,” she lied, because mothers are made of lies that keep sons upright. “Let’s not make a scene.”

But a scene had been made and published inside a hundred eyes.

Part II — Bread, Rain, and Oaths

Long before crystal and chandeliers, there had been a kitchen that smelled like proofed dough and rain. In a weathered house on the edge of Spokane, the wind taught the walls to sing, and a small boy asked why winter made the floor so loud. When Aaron’s father died, grief was a chair at the table; Norah set a plate for it anyway and learned to speak around it.

She woke when the dark was still airtight and kneaded bread with hands that had become maps—lines where years had walked, valleys where water had pooled. She sewed by the window, green thread on a red coat, blue on denim, her work a quiet war against unraveling. Children came with torn sleeves, mothers with hemming pinned in their teeth, winter with bills that didn’t bend. Norah’s life was a ledger of small rescues.

“If he grows up kind,” she would murmur to the coffee, to the empty corner where her husband used to take off his boots, “it will be enough.”

Aaron was curious and useful, which is what kindness looks like at five. He held the thread so it wouldn’t tangle, stirred stew with a solemnity that made everything taste better. “Do you get tired, Mom?” he asked once, his hand warm against her elbow.

“Tiredness means we’re still trying,” she said. “Trying means we haven’t given up.”

There were years when the house answered the wind and the roof held its water with its teeth. There were nights when dinner was bread and water, eyes squeezed shut to conjure feasts. There was a letter waved home in a trembling hand—acceptance to a state university—the page devoured by tears before the words could be.

The day after the letter, she sold her wedding ring quietly. Metal against memory, memory against future—the arithmetic only mothers and saints understand. When he found out, anger ran through him like a storm with nowhere to sit.

“You shouldn’t have—”

“A ring is just metal,” she said, her palm on his chest, feeling the engine of him. “Your future is not.”

He promised. He would make her proud. He would buy her a house where the rain slid down the windows and never came in. Promises are cheap. He made his with fire, which burns longer.

Seattle was a beast—loud and bright and hungry. He wrote code on a laptop that ran hot and burnt his thigh through the blankets he used as insulation. He went to class. He made coffee. He slept in a pattern only the young can survive. When exhaustion pressed its hand over his face, he remembered bread and rain and the quiet clock of his mother’s hands at work.

An idea came—something unnecessary to venture capitalists and vital to the women who wrote lists on the backs of calendars and forgot where they put their glasses. He built an app for the elderly, a small, stubborn thing: reminders for medicine, directions that claimed allies in the form of friendly arrows, an alert that sent a son’s phone ringing in a kitchen far away. Investors called it sentimental. He launched it anyway.

One story. That’s all it takes to change a trajectory. A reporter did a human-interest piece: a son writing code for the woman who stitched his sleeves. Downloads jumped; a partner called; then another. His company stepped out of its dorm room and took an office with windows that overlooked the water.

He took a bus home. When Norah opened the door, he looked like a man the world had decided to listen to, and like a boy waiting for permission to eat before dinner.

“I told you,” he said, placing lilies on her peeled Formica table. “Windows that never leak.”

He put her in a little house on the city’s edge where daisies behaved themselves and the porch made the evening into a ceremony. She still rose at impossible hours and fried eggs and insisted on sending him out the door with advice disguised as requests. He let her, because sometimes letting is the love you hold with both hands.

It was at a gala that Sabrina found him, lacquered and lit, a specimen acquiring everyone’s attention with minimal effort. She smiled the way people smile when cameras are nearby: generously. He had learned to recognize wolves and was tired of them. She wasn’t one—not in that first conversation. They discussed charity, and her sentences came wrapped in laughter that didn’t sound expensive. She knew his story. She admired that he wrote apps for people who actually needed them. He mistook curiosity for care. It happens.

He brought her home, and she came with flowers and chocolates in gold paper and eyes that skimmed the hand-stitched curtains and the plain chairs and catalogued them like errors. Norah offered pie; Sabrina took a mouthful and a photo for a friend later, a caption about bread dough and billionaires. Aaron didn’t hear.

Sabrina bent herself charmingly around his life: suggestions that sounded like favors, edits to wardrobe that read like compliments, a smile that worked on donors and men in suits. To the world, she was a perfect fit. To Norah, there was a draft in the room that hadn’t been there before.

“If she loves him,” Norah told the laundry, folding the corner of an old shirt into obedience, “she’ll learn the language of respect.”

The morning of the wedding arrived with rain soft as breath. Sabrina was a symphony of silk and ambition, the cathedral a gallery built to house her. Norah tied on a plain black apron over the pale dress she’d sewn herself and picked up a tray because small help is still help.

Things break. That’s what they do. A hand flies. That’s what some hands do.

Part III — The Cancelled Future

The video uploaded itself to the world like a confession that wanted witnesses. Sixteen seconds: a bride, a slap, an old woman’s hand to her cheek. Newscasters said the word elder with a solemnity they reserve for anything that makes their lips form into care. Comment sections caught fire. Sponsors called and hung up. Sabrina’s mother sent a statement that sounded like a lawyer had microwaved it twice.

Aaron said nothing for a week. He shut his phone in a drawer and sat with his mother in a kitchen where the rain tapped at the window and the clock ticked like a small, patient animal. The red mark faded in increments that felt like instructions.

“Don’t let hatred grow roots,” Norah said finally, watching his jaw clench against it. “It chokes good things that are trying to bloom.”

He nodded. Then he called a press conference.

He stood beside his mother, did not take her hand because he knew cameras would eat that gesture and spit it out as theater. He spoke calmly. “Respect for parents isn’t a quaint tradition,” he said. “It’s the foundation of any life we hope to build. Wealth means nothing if gratitude has gone missing.”

He filed charges. Public humiliation. Elder abuse. There were those who said he’d ruined a woman’s life for a mistake. He suspected she had done that herself with a lifetime of choices that taught her to swat at anything unpolished that came near her silk.

The judge called Sabrina Ms. Collins and did not soften his face when she cried. The sentence was something that sounded like mercy and functioned like a mirror: community service at a senior center for a year, no contact with Norah or Aaron, a public apology that wasn’t allowed to use the word if. Reporters took photos of Sabrina in a gray volunteer shirt carrying pea soup to a man who asked her to turn up the radio. The internet laughed. Internet laughter is how some people pay the rent on their rage.

The headlines stopped shouting after a while. Tragedy has a short shelf life unless you know someone who keeps it in the pantry. Norah healed where the skin had been insulted. Some bruises stayed in places robes and cameras can’t reach. She didn’t think of Sabrina as often as the world wanted her to, and when she did, it was with a weary kind of pity. People raised on mirrors cannot help you carry anything heavy.

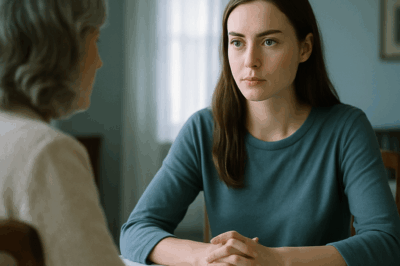

It was a cold afternoon with the sky the color of a sore throat when Norah pushed open the door to a senior center with a bag of donated blankets hanging like a promise from her elbow. She liked these halls: the smell of hand sanitizer that didn’t quite hide the smell of lunch, the sound of a radio turned low and good decisions made often by people very tired of noise. Down the corridor, a young woman in a gray shirt bent toward a man in a wheelchair and said something that made him smile.

Recognition arrived like a small stone thrown gently at her chest. Sabrina. Ponytail, face thinner, arrogance poured out and rinsed away. Not elegant. Not curated. Just a woman doing a task right and kind.

Sabrina looked up and saw her. The blood left her face the way light leaves a room when a cloud moves. She walked over like someone approaching a cliff they deserve to fall from. “Mrs. Fields,” she said softly, eyes swimming. “I didn’t think you’d ever want to see me again.”

Norah didn’t answer. She was busy deciding which part of herself should speak. Woman who had been humiliated? Mother who had been wronged? Baker who had learned mercy early because flour and water only make bread if you are patient?

Sabrina swallowed. “I can’t undo what I did. I don’t ask for forgiveness. I just need you to know I am sorry. Truly sorry. I’m… not the person I was. At least, I’m trying not to be.”

Norah stepped close enough to smell the soap and the ache. She put her hand on Sabrina’s shoulder and felt it shake. “Wrong can ruin you,” she said, voice gentle as flour on wood. “Or it can teach you. What you build next will tell me who you are.”

The girl broke, not loudly, just enough to remind the day it was carrying too much. “I’ve lost everything,” she said.

“Then maybe,” Norah said, “you can build something that wasn’t nothing pretending to be everything.”

They stood in the middle of a hall where a radio was playing a song about a kind of love the world doesn’t sing much anymore. Norah walked away without promises. Forgiveness, she knew, is water: you don’t announce it; you pour it. Sometimes in thimbles. Sometimes in floods.

That evening, Aaron was fixing a hinge on the porch that squeaked when the wind had opinions. “You were gone a while,” he said, the metal behaving under his hands.

“I saw Sabrina,” Norah said.

He stilled. “You talked?”

“I did.”

“Mom,” he started, jaw tightening.

“She’s different,” Norah said. “Life is standing very close to her and asking questions she doesn’t know how to answer.”

“I don’t know if I can ever forgive her.”

“The forgiveness is not for her,” Norah said. “It’s for us. If we don’t drop it, we carry it. And I’m tired of carrying things that aren’t bread.”

They ate in a quiet that didn’t demand language. Soup. Bread. Tea. Rain mapping the window.

“Do you wish it had gone differently?” Aaron asked at last.

“No,” she said. “Pain teaches. That slap didn’t just mark me. It marked what matters.”

“What’s that?”

“Money builds houses,” she said. “Respect builds homes.”

Part IV — The Ruins and the Blueprint

Sabrina learned the names of residents: Mr. Alvarez who told the same story about a baseball game until it turned into an epic; Ruth who had been a nurse when syringes were boiled and telegrams did the work of phones; a man who called everyone Margaret because his mind had edited the cast list. She learned how to lift safely, the kind of lilt that gets people to eat, the art of laughing at jokes whose punchlines got lost on the stairs and never found their way down. She learned humility—the hard way, like most people worth knowing.

Her family’s brand stepped back in steps so soft you might mistake them for good manners. The store went on without her. The friends with rings on their fingers slipped those fingers out of reach. The magazines that called asked for a redemption arc. She said no. She did not need the arc. She needed the work.

She kept her head down on buses and tightened her ponytail like armor. The internet moved on. She stayed. She served. And when a year turned quietly in the calendar’s hands, she didn’t leave the center. Some debts don’t end where the judge thinks they do.

Norah returned sometimes with blankets, with bread, with daisies in jars that used to hold pasta sauce. Sabrina did not ask for approval. She smiled, gentle in a way no one had taught her. Once, in the garden behind the center, they watered tomatoes in silence. “My mother used to grow these,” Sabrina said, surprising herself. “I hated getting dirt under my nails.” She laughed—soft, rusty. “Now I don’t feel clean until I do.”

Norah handed her a towel. “Some lessons you can only learn by kneeling.”

Aaron ignored Sabrina in public and prayed for her in private, which is to say he did what people do when they’re not sure which part of themselves they respect more. He did not date for a while—not because the city stopped offering, but because the men who don’t make a scene are the ones you want at the end of a world, and he was tired of being interesting to people who practiced interest like a sport.

He poured himself into the company. He added a feature to the app that allowed users to record a story each day—memories captured while they still behaved. The servers began to fill with small pieces of human weather: a man describing a bicycle he’d had when the war ended; a woman listing her children’s names in order and then again just to prove she could; a quiet voice reading the recipe for the bread she made on Sundays when there was nothing in the house but hope and flour.

He recorded one too: his mother’s laugh. He played it sometimes when the night wouldn’t sit.

Part V — The Second Chance Nobody Asked For

A year after the slap, a fundraiser for a different charity sent invitations in fat white envelopes. People still wore suits to these things; they still pretended to be natural inside rooms that demanded performance. Aaron saw it as an opportunity to announce a new initiative—free licenses for elder-care facilities—a tangible thing that helped and not an applause line. He told his mother it would be quick. She told him to take an umbrella.

Sabrina was there too—not on a list, not on a red carpet, just… there. She had come as a volunteer to collect silent-auction bid sheets and tell donors their penmanship looked expensive. She kept her hair in a low bun and wore a dress that didn’t require a diagram. She had learned to look people in the eye without flinching. Some of them knew her. Some pretended not to. She had gotten good at reading shoulder blades, the way they tilt when someone is deciding whether you are a shame they can afford.

She saw Aaron across the room and considered exiting her skin. Instead she sat down with a man who was having trouble tearing the paper ribbon from a bouquet. “Let me?” she asked, hands steady, voice kind. She did the thing. He said thanks like he meant it. She didn’t look up when Aaron passed behind her. He did, a little; a small tension moved through his jaw like a rope pulled and eased.

Onstage, he spoke with his usual economy—gratitude, partnership, numbers that landed lightly, not like boasts, but like invitations. “We build tools for people we love,” he said. Camera flashes behaved. Later, in the coatroom where fur pretended to be climate, Norah hugged her son and patted the umbrella she’d insisted he bring. “Proud of you,” she said, because those words don’t get old.

Sabrina stepped into the hall by accident at the same moment. Norah saw her first. She touched Aaron’s sleeve lightly, the universal sign for “choose your best self.” He exhaled. Sabrina froze. The coats watched.

“Ms. Collins,” Aaron said after a second, his voice careful, not cruel.

“Mr. Fields,” she said, matching his formality, the consonants steadying her on a floor that still sometimes moved.

“My mother tells me you’re… still at the center.”

“I am,” she said.

“She says you’re different,” he said, a small astonishment in the words.

“I’m trying to be,” she said.

“Then… good,” he said. It wasn’t forgiveness. It was something else: acknowledgment that people are not museums. They are construction sites.

Norah leaned her head briefly against his upper arm the way you do when neither hug nor distance is right. “Let’s go home,” she said. The umbrella looked delighted to be useful.

Part VI — The Last Lesson

Years resolve themselves into a rhythm when you’re lucky and into an obligation when you’re not. Aaron’s company grew at a merciful pace—fast enough to keep adrenaline interested, slow enough to keep integrity unconfused. He hired people who talked to their grandparents. He learned to leave the office at a reasonable hour. He taught himself to make omelets without Googling it. He found himself laughing at a joke a woman at a bookstore made about the endings of novels, and he let himself ask if she’d like coffee. She would. It wasn’t a movie. That was good.

Norah slowed. The steps up to the porch began to argue. Her hands still remembered knives and needles and heat, but they asked for breaks mid-task. She liked being asked her opinion on things that didn’t matter and giving it as if the world depended on it. She liked daisies; they liked her back. On Sundays she made soup and invited anyone who looked like they might eat soup if told them to. She did not speak often about the slap. When she did, it was to remind herself that anger had tried to rent a room in her chest and she had refused the application.

Sabrina kept working. She finished her required hours long before the calendar expired and didn’t stop. She took classes in caregiving and lifted properly; she learned to say goodbye without taking it personally when someone couldn’t find the word for her name. She saw Norah sometimes. They never pretended to be something they weren’t. They didn’t pretend to be what the internet wanted either: enemies or best friends, narrative conveniences. They were two women, one of whom had done a harm and was doing the work of not being that harm again, the other of whom had been harmed and refused to let it calcify the warm parts of her.

Once, near the end of a day that had asked too much of everyone, Sabrina found Norah in the center’s garden, pruning something that looked like it would stab you for trying to help. “I don’t know how to make it better,” Sabrina said suddenly, the sentence escaping before she could cage it. “The world still hates me. Sometimes I still hate me.”

Norah snipped a thorn and flicked it into the dirt. “Better is not a destination,” she said. “It’s a direction. Face it and keep walking.”

“Do you forgive me?” Sabrina asked after a long breath, a question that deserved to sit in the air for a while.

“I forgive you because I like breathing,” Norah said. “That doesn’t erase it. It makes space around it.”

They stood, two gardeners learning the same lesson from different plants.

On a midsummer evening that smelled like grilled corn and a neighbor’s indecision about music, Aaron carried a box onto the porch. “What’s this?” Norah asked from her chair, the one that had learned her shape.

“A surprise,” he said, an infrequent announcement because he had inherited his mother’s suspicion of surprises.

He opened the box. Inside, wrapped in tissue paper like a gift from a fancy store, lay a dress. Pale blue. Simple. Hand-sewn by a tailor who had listened to a son describe the exact way a stitch should look because he remembered it from a kitchen in Spokane.

“Windows that never leak,” he said, because promises want to be said again.

She laughed, the sound he had recorded and kept in a server and in his phone and in his chest. “You and your oaths.”

He helped her stand. The city did what cities do: shone. Church bells remembered how. Somewhere, a radio played a song so old it had become new again.

“Do you ever wish you’d had the wedding?” Norah asked, not unkindly.

“I do,” he said. “Not that one.”

“Maybe another,” she said, smiling, eyes gone clever. “With someone who knows how to carry a tray. Or at least how to apologize without a camera.”

He rolled his eyes, and love filled the space between them.

“I want to say something,” he told her, sudden and earnest, as if he were five again with a frog cupped in his palms. “Thank you.”

“For what?”

“For the bread,” he said. “For the ring. For the hands that never learned to stop.”

“Then you do something for me,” she said, that old mischief rising. “Call her.”

“Who?”

“The woman with the bookstore laugh. Don’t keep me waiting for grandchildren I can feed soup to.”

“Mom,” he groaned.

“Soup freezes,” she said. “Time doesn’t.”

They watched the light run out of the day in a long, soft pour. After a while, he went inside to call. She sat there, a queen with daisies for scepters, and let memory and the present share a chair.

The clear ending, then, if you need it in words: A wedding ended. A habit began. Sabrina learned to serve for real, without applause. Aaron learned to trust again, this time like a person who knows the value of windows that don’t just look pretty but keep weather where it belongs. Norah did what she had always done: chose kindness with a spine. The scandal became a story the city told itself when it wanted to remember what mattered: that money builds houses and respect builds homes; that a slap can echo, but so can an apology; that a mother’s worth cannot be calculated in silk or sponsors but in the way she turns scarcity into bread and boys into men.

Before bed, Norah checked the locks, watered the stubborn plant, and stood at the window for a moment, fingers resting on the glass. She whispered a sentence that had kept her moving when the world wanted her still.

“Thank you,” she said to the room, to the night, to the chapter behind and the one ahead. “For everything that didn’t happen, and for what did.”

And the rain, polite as ever, stayed on the other side of the window.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

An Unknown Number Called Me It Was His Ex What She Said Shattered Everything I Thought I Knew

An Unknown Number Called Me. It Was His Ex. What She Said Shattered Everything I Thought I Knew Part…

I GIFTED MY PARENTS A $425,000 SEASIDE MANSION FOR THEIR 50TH ANNIVERSARY. WHEN I ARRIVED, MY MOTHER

I gifted my parents a $425,000 seaside mansion for their 50th anniversary. When I arrived, my mother was crying and…

HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am

HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am Part I:…

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side?

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side? Part I — The Unicorn…

“We’re Taking Your Lake House For The Summer!” Sister Announced In A Family Group Chat. I Waited…

“My sister said, “We’re taking your lake house for the summer,” and everyone in my family agreed. They drove six…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes… Part I: The Answer…

End of content

No more pages to load