The Bank Told Me I Owed $600K on a Mortgage I Never Signed Turns Out, My Dad Used My Name!

PART 1

The pediatric wing smells like antiseptic and orange juice. It smells of disinfectant and small triumphs: a temperature back down to normal, a stitch that held, a fever that finally broke. On most days that was enough to keep me walking steady, to anchor me in the rhythm of the hospital—vitals, charts, syringe trays, the hum of the suction machine. I was mid-shift, leaning against the doorframe of Tyler’s room while he proudly rebuilt a Lego tower he insisted would never fall, when my phone vibrated in my pocket.

I almost let it go. We learn to be absent to interruptions when a child’s oxygen level is the thing that matters. But it was a local number. Against my better instinct I answered.

“This is Sable Whitaker,” I said, expecting perhaps a vendor or a coworker.

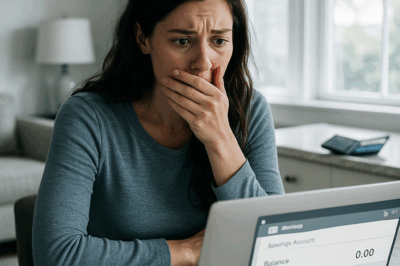

A man’s voice responded—crisp, corrected. “Ms. Whitaker? This is Craig Donovan with Cascadia Bank. I’m calling in regards to your mortgage for Highland Drive. Our records show you are ninety days delinquent.”

There are few sounds that carry the weight of a life rearranged. His words hit like one of those small yet sharp punches you never anticipate: mortgage, sixty thousand, three months overdue—no, not sixty—six hundred thousand. I braced myself on the hospital hallway wall, the fluorescent lights turning everything a little too honest.

“No,” I said, because denial was the only immediate tool my mind offered. “I don’t have a mortgage. I don’t—”

He asked me to confirm the last four of my Social Security number. I hesitated. Then I gave them. He read them off. Correct. He rattled off a listed income that was nearly double anything I made as a pediatric nurse. He had a credit score in the high 700s associated with my name that I had only ever dreamed of. He read off the address: Highland Drive, a house on Queen Anne with the view people in the city whisper about when they want their friends to be a little jealous.

When I hung up, my hands shook. Tyler dropped a small Lego piece down the vent with a thud and looked at me with the solemnity of a person who had just watched gravity do its work. I forced a smile, swept the Lego from the carpet, and told him we’d build it again. It was what nurses did: we held small worlds steady even when our own spun.

That night I slept little. My life was modest—an apartment above a coffee shop in Ballard, a mail locker I’d reinforced after someone lifted my neighbor’s packages, plants that leaned into light like eager students. I paid bills on time, lived within the clean lines I’d drawn after my parents’ death, felt comfortable in the even ache of routine. I had never applied for a mortgage and certainly not for a house that cost six hundred thousand dollars.

When I went to Cascadia the next morning, rain made the city a smear of grey and sound. Richard Peterson met me in a glass-walled office and slid a thick file across the desk. He tapped the header where my name sat beneath the notation: loan application—Highland Drive. The pages smelled faintly of toner and sealant.

There was my signature on line after line, an elegant curve I recognized because my father had taught me how to sign properly when I was young—how to press a pen so the stroke could not be lifted, a sort of defense against fraud. Whoever had forged it had known that detail. Whoever had forged it had copied the way I had been taught to make my name irrevocable.

There were pay stubs I had never given, an income inflated as if someone wanted to qualify me for the highest loan tier, a notary’s seal—real, registered, the name of a notary I had seen on county documents. The deed of trust recorded at the county recorder’s office. Everything looked legal, immaculately prepared. Everything shouted a lie.

I walked out of the bank carrying copies, the drizzle through the office window making my cheeks cold. I put fraud alerts on all three bureaus, filed an affidavit with the Federal Trade Commission, and called the Seattle Police Department’s Financial Crimes Unit. Detective Rowan Hail, who smelled faintly of coffee and wore an expression that never quite allowed for hope or panic, took my statements.

“We traced the application to a fixed IP in Georgetown,” he told me, which should have been meaningless until he added, “where your father’s workshop is registered.”

Georgetown. I could smell it in my mind: sawdust, oil, the bitter tang of stain, the memory of small hands sweeping floors to earn ice cream coins. That place had been a backyard kingdom when I was a child. Now the map had folded on itself and returned my home in the most treacherous way.

Detective Hail showed me title searches, rapid closings, a cash-out refinance scheduled like a second theft. Contractor liens stacked behind the property—bills unpaid, invoices floating like paper boats in a storm. My father, Dorian Whitaker, had been a builder long enough that neighbors came to him when they wanted a porch that would last generations. They trusted his name because he had built it into the wood and foundation of the community. Watching those files was like watching the scaffoldings of that trust fall away.

I called my mother first because she was the one who preferred to keep scaffolds upright. “Don’t go to the police,” she said in a voice that trembled as if the walls of the house might listen. “We should handle this as a family. Dorian—he’s proud, but he’s not a criminal.” The word ruin trembled from her lips in a quiet panic. As far as she was concerned, everything could be smoothed over. As far as I was concerned, my name, my credit, my life had already been used as plywood in some desperate structure.

I didn’t tell her that the IP address matched my father’s workshop. I didn’t tell her that a title officer named Tessy had pointed out preparer phone numbers and circled my father’s cell on the deed. She might say, Let us fix it, or worse, make it small. Families fix their own walls, she had said. I thought about the unbalanced ledger: parents who asked their children to be the scaffolding of their later lives, then quietly remodeled those scaffolds into cages.

If you forge someone’s name to buy a house, if you draw their life into debt, if you plan their future as if it were a ledger to be manipulated, you are not saving a family. You are collapsing a person into a line item.

Detective Hail did what detectives do well: he turned a personal crisis into an investigation with steps. He pulled IP addresses, examined handwriting samples, traced cell phone registrations, and seized a laptop. He found spreadsheets in which a bankruptcy petition had been prefilled with my name, Social Security number, employment data—letters of hardship already drafted as if the plan were to throw me into court as the author of my own ruin. It was not panic. It was calculated.

The day I walked into my childhood house with the police report in hand, I felt like I was balancing something that should not be in my palms. The maple table held the entire history of birthdays and fights, pies and reconciliations. I set the packet down and the paper sounded like a hammer against wood, an insistence in the dining room’s soft conversation.

My father’s fork clattered onto porcelain. He looked smaller than a memory should. “What is this?” he demanded, eyes darting to the header, to his own hand’s shakiness I had seen in the years after projects began drying up.

“It’s the police report,” I said, and the voice felt both distant and bright. “You filed a mortgage in my name. You forged my signature. You attempted to sign me into bankruptcy.”

It happened like a slow, fatal unfolding. He tried the old defenses—a laugh, a joke, a petition to family—before the documentary truth took its place. Detective Hail, whom I had asked to call, spoke. He explained the IP traces, the bank statements, the title preparer number with my father’s cell. The room condensed.

“You meant well,” my mother whispered, as if intention could be a blanket for a house on fire. “You meant to save us.” I thought—then and many nights after—about the difference between intent and impact. The desire to keep a family afloat can’t become a boat built on someone else’s life.

My father’s admission in court was not cinematic. There were no grand denials. There was a tired acceptance and then, when the judge asked him to state his name and acknowledge the charges, a kind of collapse. He used my information, he told the courtroom in a voice small as a nail. He admitted to copying documents and to filing documents under my name without my knowledge because he thought he was saving the family business by borrowing my credit as collateral. The judge’s gavel fell like a deliberate punctuation: 18 months, restitution, supervised release.

The legal consequences were not the end of suffering; they were the only formal measure of justice available. Cascadia Bank removed the mortgage from my file. The bureaus scrubbed derogatory marks. The King County Recorder’s records were annotated. A reconveyance moved through the clerk’s office like a quiet editorial correction. The Highland Drive property—already a charred symbol of my father’s hubris—fell out of his ownership as contractors and banks and courts negotiated the pieces. He took his sentence and left me with the echo of his explanation: because family, he had said. Because I was his child; because the building of a legacy is a kind of claim.

Neighbors who had once admired his porches now whispered as I walked through the market. People who had seen him as a standard of workmanship pointed and closed their doors. I walked back into the Georgetown workshop the day the police hauled boxes of invoices and laptops. The smell of sawdust, once warm, had turned clinical: evidence tags, numbered boxes, a quiet that had the rhythm of loss. The childhood memory of hammering alongside him dissolved into an adult understanding of how someone can bury greed under the guise of craftsmanship.

At the table that night, my mother wept in a way I had not seen since my father’s falls from grace became visible. She was not weeping for the man who had broken the law; she was weeping for the child who had to choose between filial piety and self-preservation. She had wanted walls that could be repaired within the family circle. But the family was a house with cracked supports, and the only way to keep the rest standing was to expose the rot.

The weeks after the indictment were a blur of court dates and paperwork and the slow, practical work of repair. Detective Hail was efficient and unromantic. He coordinated with Cascadia to ensure that any notes or liens were held from my file. The bank’s legal team worked with my lawyer to rescind the loan applications associated with my identity. It took time; bureaucracies move with a sluggishness that is patient on the side of wrongdoers.

There were small humiliations that lawyers can’t fix: an awkward conversation with the HR director at the hospital about the credit report, a supervisor’s raised eyebrow when an employment reference required a background check. Each time I showed the documents—police reports, court dates, the judge’s order—people’s faces shifted from a rumpled skepticism to an embarrassed kindness. There is a half-grace in being believed once a credible authority confirms your truth. There is also a long tail of consequences when your name has been used as a tool.

When my father was convicted, the immediate practical consequence was the removal of his access to assets. He owed restitution, and he owed the emotional work of facing not just the law but the people he had betrayed. The sentence was, in a way, a kind of cleavage in our family story. Some relatives called me venomous for what they called “airing private business.” Others, more quietly, thanked me for choosing truth over an easier silence.

I felt neither triumph nor simple sorrow. What I felt most was relief, threaded with an ache that no court could return to its rightful place—the comfortable assumption that parents are the shelter of children. My father had become the kind of danger I used to protect others from as a nurse but could not patch at home with a bandage.

A month later, contractors served mechanic’s liens, and neighbors filed claims. The Highland Drive house—a taut dream of views and barbecues—slid through the procedural gears toward foreclosure and eventual reconveyance. Cascadia accelerated the loan as per their terms before rescinding due course, and in the interim the property’s window gleam became a public symbol of his loss rather than the private vantage point he had imagined.

I sat in courtrooms and watched my father sit next to the defense attorney, hands folded, his face hollow, the man who once taught me how to wield a hammer reduced to a figure who had misused his child’s life. When the judge read the sentence she looked at him as if she saw the blueprint of his life and the cracks that had formed. “You are not above the law,” she said, in her steady tone. “Entitlement does not make a crime humane.”

That image stayed with me: the judge’s hand on the gavel like a compass pointing to a kind of moral north. There was a safety in the accountability of systems, in the way law could, however slowly, right a wrong done on paper. But law does not stitch closed the absences left in the heart. My mother moved out for a while to a sister’s house in West Seattle; she needed distance to breathe without the possibility of being pulled back into the drama. Contact with my father became structured and supervised. We spoke in narrow channels.

Two months after the last hearing, I signed papers for a small bungalow in Ballard. The mortgage—my mortgage—was modest and clean. I signed each page with the careful, deliberate pressure my father had taught me but this time the pen pressed for me and by my choice alone. When the notary slid the new deed across the table and I felt the cool plastic sleeve, it had the weight of a small redemption. It was a house with a yard, a shed, a mailbox that did not need bolting. The first thing I planted was a young dogwood. It seemed, in a way that made my chest ache, like an act of naming: a small tree for a new beginning.

At night I would lie awake and think of that maple table, of the cracked china and the slurred apologies my parents would make when they thought the house of their choices could be repaired by regret. My mother called often. Her voice still carried shame that I could feel under the words. Sometimes she asked what she might do to help me heal. “You hurt,” she said once, and I could hear the force of honesty in it. “And I didn’t see it.”

I wanted to be firm and kind both, because our history was complicated and I was not a cruel person. I told her I loved her but that protecting myself had to be the priority; that lessons about boundaries were also lessons of survival. She began counseling and we began to meet with a therapist arranged through the hospital’s employee assistance program—to untangle the threads of my obligations and her defenses, to turn suffering into something we could speak of instead of a buried thing we avoided.

There is a particular kind of stubborn feminist resilience in nurses: a willingness to keep showing up. I returned to the pediatric wing with a smaller heart ache and a new handle on the ways people manipulate loved ones. The patients’ victories—glasses of water kept down, the relieved cough after the wheeze glided away—felt meaningful in a world that had otherwise tried to map my life as a ledger. I poured my attention into practical things: freezing my credit, re-checking my accounts, locking down my health records, putting my deed in a safe.

Tessy the title officer was a narrow woman with sharp, practical eyes who sent occasional emails checking in. Detective Hail called less frequently but adequately; the case wound through the legal gears, and there were consequences: court dates, restitution orders, a sentence that felt like both a legal and moral verdict. My mother visited my new house once; when I opened the door I saw her move as if into a new room in her life, her feet unsure of the floorboards, but steadier with each step.

I taught myself, painfully, the difference between love that stifles and love that supports: parents who see their children as an extended resource for their own shame or failings are, in effect, taking from the future of their children to prop up their present. There are times when family cares for each other without asking for payment; there are other times when generosity becomes an expectation—an unpaid bill. I decided to refuse the role of unpaid bank in my life. I refused it with the firmness that courts could measure and with the softer bravery that the heart must hold.

When the first spring after the trial arrived, the dogwood in my yard bloomed a tentative white. It looked like the answer to something, like the best small mercy you can plant for yourself: something that grows slowly and will stand for years you might not be around to see. I pruned its branches, fed the soil, and told it, once, under my breath, that it should be stubborn.

PART 2

It’s strange how, after a storm, the clean-up is the part that takes the most honest time. The legal machinery did what it did: my father served his sentence, the bank adjusted its ledgers, and my name stopped carrying the weight of a debt I had never authorized. But the more intimate work—healing the hollow places, reweaving the threads of trust that had frayed—slid along a slower, invisible clock.

I started going to counseling regularly. The hospital’s employee assistance program offered sessions with a therapist who specialized in trauma and family dynamics. Her name was Dr. Morrison, and her office smelled of pencils and quiet blue paint. We talked about betrayal in layers: the pragmatic betrayal that had come with forged documents, and the deeper, quieter betrayal of a child who felt used by a parent.

“You have rights,” she told me on the first session with an evenness that felt like a lamp put on in a room I’d been sitting in with the lights off. “You also have grief. You have the right to both.”

I hadn’t known that the two could sit together—I’d thought reclaiming my name meant I couldn’t feel anything softer. But grief arrived like winter light, clear and cold and precise. I grieved not only the future my father had stolen from me but also the man I once knew—a hammer in the hand, his laugh in the workshop—who had turned into someone capable of forging a child’s life. Grief, I learned, is not the same as hatred. It is a landscape through which you build pathsto rebuild.

Volunteering eased me. I began working with a nonprofit that supported victims of identity theft and mortgage fraud—people whose identities had been used like scaffolding and then abandoned. I sat with them across small cafeteria tables, showing them how to file affidavits, how to freeze credit, and how to call the recorder’s office. Sitting with their stories made my own less solitary. We would trade the small rituals of proof: printouts of deeds, redacted bills, notarized affidavits. It turned raw paperwork into something that was, at least, useful.

There were still awkward moments. My father reached out through structured channels for the months he was released under supervised terms. We had two conversations, both mediated by a probation officer. The first was raw. He said, “I thought I was saving the family.” Saying those words aloud felt like tearing a scab. I said, quietly, “You did this to me. That is hard to undo.”

“How can I make this right?” he asked, and for the first time in my life he didn’t ask me to pretend the answer was easy.

“You can accept the consequences,” I said. “You can make restitution. You can understand what you did. You can show up, not as someone who expects forgiveness, but as someone who respects the process of being forgiven.”

He tried. He did some of the things: restitution, a letter to the court with contrition, participation in a program on ethical decision-making for small-business owners. Whether those efforts would sew him back into the fabric of family was another matter. My mother visited him in the halfway house once, bringing a pie she didn’t finish. She told me afterward that those visits were a kind of confession for both of them: acknowledging collateral damage and trying to pick up some thread.

There are people who write that forgiveness is a requirement of the wounded. It isn’t true. Forgiveness is the wounded person’s luxury—or perhaps their tool; you choose. I chose to set boundaries first and consider forgiveness later, if at all. I could not unmake the past. I could, however, build a future that wasn’t a copy of the one he had designed using my name.

Work remained my anchor. In the hospital I had a different kind of authority: the power to help a child breathe or to explain to a frightened parent how a course of antibiotics would heal their child’s chest. Those moments—small, human—became my daily proof that life is about living into care, not into debt. The families I helped often reminded me of resilience in ways no courtroom ever could. One evening a mother told me, half out of breath and half laughing, “We got through this, Sable. Kids forgive easy. It teaches you how to forgive yourself. Maybe that’s a thing you’re teaching adulthood too.” I nodded at her and felt the truth of it: people survive; they forgive some things and not others; they keep building.

As months turned to a year, I noticed the dogwood in my yard had small buds. Spring arrived like a patient student. White flowers unfolded in groups, each petal soft as an apology and bold as a demand. I trimmed the branches and watched bees find the blossom like they always have for flowers. Neighbors would ask me what kind of tree it was, and I would tell them: dogwood. They would smile and say it was beautiful. The dogwood became my small victory: a living proof of a plan that didn’t borrow from anyone else’s life to survive.

The nonprofit’s director asked me to speak at a workshop for small-business owners about the ethical use of names and signatures. I prepared a talk that was half practical—how to avoid falling prey to identity theft—and half personal. I told the room about signatures taught as a defense and then weaponized. I told them about the courage it takes to call the police on your own parent. There were quiet faces and hands raised slowly. No one judged me for the choice. Their silence was a kind of respect for the hardness of what I had done.

Family things, as they do, had moments of softness and relapse. My mother and I began a rhythm of weekly calls that were honest but not raw, a way to practice being present without reopening the wound. She apologized in a way that made sense for her: not a single dramatic confession but a change of pattern—more calls, small gifts (a jar of jam she made), a willingness to come to counseling with me. She began to see how her desire to keep the family’s mess private had inadvertently benefited the person who committed the fraud. “I wanted to protect him,” she said in a counseling session, “because I couldn’t watch him fall apart.” We unpacked that impulse together.

As for my father, he mailed letters from the halfway house. In one, he wrote, “I see now how wrong I was. You were a scaffolding, not because I loved you less but because I loved the idea of my family’s safety more than your life.” He wrote poorly and in a hand that trembled. I never answered the letters in anything like a full reconciliation. Sometimes I would write a line or two: “I received your letter. I am getting the support I need. That is what matters.”

There were social consequences too. People who had once assumed my father’s correctness closed their houses to us, and some neighbors who had admired his work were now suspicious. The gossip teeth had their own appetite. I learned to accept small social casualties as the price of a stable identity. You cannot keep everyone on the same page when your family’s story has been rewritten.

Two years after the trial, my mother suggested a family gathering that would include my father. I resisted at first and then agreed to a short lunch at a neutral café, because I wanted to measure what, if anything, had changed. The meeting was small—my mother, my brother who lived in Tacoma and who had been mostly quiet throughout the whole ordeal, Detective Hail (quietly invited as a presence to defuse tension), and my father, who had the pallor of someone who had paid a kind of public cost. The conversation was halting. At one point my father said, simply and plainly, “I’m sorry.” He had to do it more than once before I felt it permeate, and even then I understood apology is only a paper patch over a larger structural problem: trust.

After lunch I walked to my car and thought about the dogwood, how small it had seemed when I planted it and how now it shaded my yard with blossoms. I felt something like relief. Not the ring of absolute restoration, but the peace of forward motion.

In the third spring a neighbor—a retired carpenter—told me he’d been at a job and saw the footprint of my father’s earlier craftsmanship and had an odd pity for the man who had once been so precise. “People make mistakes,” he said. “Some are tools; others are terrible things, but the work remains.” I listened and thought about the difference between tools and people.

There was a peculiar secondary victory that is, in many ways, less satisfying but practical: as I helped others navigate the confusing world of credit bureaus and recorder’s offices, I began to build a reputation for being thorough. I was invited to a radio show to talk about identity theft, and a local newspaper did a feature about how families could recover from internal financial betrayals—how to push back without erupting into ruin. My presence in that story became something like a public armature for private healing: the quiet woman in Ballard planting trees and speaking up.

Repair is not linear. There were nights—like the ones after the signature had been found, after the hearing—when the old memories would rush in: a smell of sawdust, a laugh in a voice that had once been an anchor. I would think of small, banal things he used to say—“Press hard so no one can lift the signature”—and feel the double-edgedness of memory. I would also think of the children I helped in the hospital, of the little victories of a child’s fever breaking, of a mother’s grateful clasp of my hand. Those were the truths that were big enough to be the foundation.

Midway through my new life I found my father outside my house once, long after his release. He had a long way to go before I could accept unmeasured visits; part of the supervised plan was to allow minimal contact. We spoke over a fence, because boundaries felt like a good way to protect both us. He apologized again. “I tried to give you something I thought a Whitaker should have,” he said. “But I wrapped it in your life and I didn’t ask.”

“I don’t want the house you built on me,” I said. “I want your presence in the life you have. If we can’t do better than that, then the arrangement is not worth it.” He nodded. He had no tidy answers. He had a probation officer’s list and a restitution plan. It was a sober transaction.

When the dogwood bloomed, I invited my mother over and we sat under the tree and ate strawberries. The air smelled like wet leaves and the city’s mundane hum in the distance. My mother told me she had started to teach a small community class on budgeting to older women in her church—practical things, she said, the kind of skills she had never taken time to learn. The small things—budgets, letters of an apology, the willingness to go to counseling—are the scaffolding of a life that refuses to repeat the same erasures. They are not spectacular. They are durable.

Years passed in that steady pulse. I dated in small, cautious ways. I dated men who cared for the world in small hands-on manners: a bike mechanic who taught me to fix a flat tire and a teacher who loved the quiet of suburban mornings. Relationships with my family were redefined. My mother and I had rituals: we spoke twice a week and she came on Sunday mornings to drink a cup of coffee and fold laundry with me. My father remained in the outer circles of my life—not erased, but rearranged. He volunteered in a community program where he taught skills to young men, supervised by a nonprofit that had a clause for people rebuilding after felony convictions. It felt like a kind of penitent work; I liked that he did it, though I never allowed him full access to my life.

Sometimes people ask me if I regret what I did, if turning in your own father is a moral line that you cross only once. My answer is always the same: I don’t regret protecting the life I had to keep for myself. I regret the suffering that the truth caused. I regret that my parents were broken in ways that had to be exposed in the public record. But I don’t regret that I chose my name.

On quiet Sundays I would sit in the kitchen, watch the sunlight make dust motes into galaxies, and think about the signature I press down hard now. It’s a small ritual that no longer carries the weight of inheritance but the measure of choice. Sometimes I write letters to people I’ve met through the nonprofit—names of other victims—and I sign the bottom: Stay steady. It feels like a small survival liturgy.

The dogwood’s first big storm taught me another lesson: roots are surgical. They split in search of water, they bend toward the light, and they hold fast when the wind tries to tear them. I pruned it one night after a gale had broken a small limb. The next spring the tree was taller; the break had made room for two new branches that reached further into the sky. I thought of that when I went to bed: a tree can be broken and still grow; people can be too.

If there is a tidy ending to this story—and tidy is a dangerous word for anything grown of people and law—it is that I learned to build a life that cannot be stolen on paper. I learned to keep my documents in a safe, to check my credit twice a year, to teach the tools of protection to others, to plant trees and listen to their slow progress. My father carried his sentence and his restitution and the private mourning of a man who preferred the idea of legacy to the life of a child. My mother learned to choose openness over protection of a man who had been wrong. The hospital work kept me rooted in a practical compassion that always returned me to the present.

A decade later, when the dogwood had grown tall enough to shade the front porch and the neighbors stopped by for lemonade, someone asked me what I had wanted most in that year of storms.

“Stability,” I said.

“And did you get it?”

I looked at the blossoms and then at my hands. “Yes,” I said. “In the way a house is a plan and a tree becomes a shade. I got something I paid for with knowledge and courage and a lot of paperwork.”

The legal records remained in the county archives. The Highland Drive address was an errant footnote in my father’s story. My name was in my own deeds. The dogwood bloomed each spring as a small witness. It is not the dramatic epiphany some expect in a story of family betrayal and restitution. It is the ordinary accumulation of a life made steady again: a job that matters, friends who know the old story and still come to visit, a mother who learned to ask before she saved, and a father who learned the price of misguided protection.

If someone asks me what I would say to my younger self—the one who signed forms without seeing the architecture of consequences—I would tell her to learn the word boundaries as early as she learned thrift. I’d tell her that signatures are not a shield unless you sleep under a roof you chose. I would tell her that the law may take a long time to be neat, but there is a kind of legal housekeeping worth doing: your name is yours.

The last time I saw my father in person was on a late-spring afternoon at the halfway house release center. He came with a box of tools he had stripped down and re-oiled, like a man who had learned to do small things well again. We sat on a bench outside and watched two teenagers kick a soccer ball across a patch of grass. He said nothing for a long time and then simply asked, “How is the dogwood?”

“It’s blooming,” I answered. “It’s stubborn.”

He smiled, the way a man smiles when survival has taught him humility. “Good,” he said.

It felt like a small, working reconciliation—less a full forgiveness than an acknowledgment of consequence. I kept my safe, my deed, and my phone. The milestones I marked were modest: final restitution paid, the dogwood’s third year of bloom, a community workshop that suddenly had double the turnout because word had spread of it being useful. The small joys were enough.

The house I bought with my own name on it held the morning light differently each day, and I learned, finally, to look at the horizon not as a place someone else had plotted for me but as a space I could choose to build in. The bank had once told me I owed six hundred thousand on a mortgage I never signed. The truth turned out to cost more than money; it cost the illusion of a simple, comfortable family myth. But perhaps the better price was paid when I reclaimed my name, planted a tree, and learned the length of roots. The cost of that lesson was real. The life I rebuilt is steadier.

My mail comes under my name now. My mother visits for Sunday coffee. I teach workshops for people who come with sealed packets and frightened eyes. I show them how to see the numbers and the signatures and the small signs that build into a life. And when the dogwood blooms each year, white as a soft defiant thumbprint against the gray Seattle sky, I go outside with a cup of tea and tell it, quietly, that it is allowed to claim space and grow.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Mom Stole My Credit Card and Drained My Savings Because I Refused to Pay $15K for My Sister’s. CH2

My Mom Stole My Credit Card and Drained My Savings Because I Refused to Pay $15K for My Sister’s. PART…

‘You need to move out. I’m pregnant and can’t have an outsider in MY home.’ That’s what she said. In MY house. That I bought with MY parents’ life insurance. CH2

“You need to move out. I’m pregnant and can’t have an outsider in MY home.” That’s what she said. In…

WOW: Under huge public pressure, Bad Bunny finally announced that he would not perform at the Super Bowl halftime show.

Immediately, Pete Hegseth added fuel to the fire when he affirmed: “It was the right decision, otherwise he would have…

Behind the scenes, producers were scrambling. The supposedly controlled segment descended into chaos as Karoline Leavitt revealed a series of shocking truths that Crockett had no time to defend. Witnesses say she called out to the host for help, but no one came. Then she walked away. Fans quickly nicknamed Karoline Leavitt “The Hammer of Truth,” praising her calm hosting and fearless tone. And while critics were harsh, they also admitted: Crockett was unprepared, and the consequences were dire…

🔥🎙️ “THE HAMMER OF TRUTH: Karoline Leavitt Silences Jasmine Crockett in Live TV Showdown — Chaos Erupts Behind the Scenes as…

THE CAMERA DIDN’T BLINK — AND NEITHER DID PETE HEGSETH.

On live television, with millions watching, he broke ranks in a way no one saw coming. ABC thought they were…

Pam Bondi, Erika Kirk, and Megyn Kelly Took The Mic.

THE ROOM FROZE WHEN SHE WALKED IN — AND EVERY CAMERA TURNED. Pam Bondi, Erika Kirk, and Megyn Kelly Took…

End of content

No more pages to load