Stepmother Cut Her Hair to Make Her Ugly—But What Happened Next Would Shock You!

Part One

The scissors were older than the woman who held them, older than the mud walls and the hibiscus hedge that fenced the compound in a red embrace. They had belonged to someone’s grandmother once—meant for cutting cloth, not girls. Yet here they were, hungry in the dark, opening and closing in the hand of Madame Obi as she hovered over the sleeping child whose beauty the village could not stop naming.

Amara breathed softly, lashes resting like shadows on mahogany cheeks. Her hair—a river of night, thick and long and faithful—spilled across her mat. The first cut was clean, shockingly easy. A rope of hair dropped to the earth with a sound that was no sound at all. The second cut was ragged, then the third frantic, and by the time the moon slid beyond the rafters, the mat was carpeted with evidence and the girl’s head was a map of cruelty—tufts here, bald there, beads clinging to the ends of orphaned braids like survivors to driftwood.

Madame Obi stood back, chest heaving, mouth curved into a sweet shape that did not reach her eyes. “If I can’t kill her spirit,” she whispered to the white ants busy with the doorframe, “I will dull her glow.” She wiped the scissors on her wrapper, left like a shadow, and the house returned to the sound of a girl sleeping in the ruins of her inheritance.

At dawn Amara woke and met the mirror. She did not scream. The scream belonged to the neighbors and the goats and the birds who burst from the iroko with a clap of wings when word ran around the compound like a child who’d seen a marvel. Amara lifted a hand to the battlefield of her head and felt not grief, not yet, but the strange metallic calm that comes when a blade finds bone and there is nothing left in you that can break.

She reached for her mother’s scarf. It was the last thing that smelled like rain and palm oil and cool laughter. She wrapped her head with the care of a priest dressing a god, tied each knot as if fastening a prayer to a new altar, and walked outside to where her stepmother stood on the veranda in a cloud of menthol smoke with a something-wrong sweetness tugging at her mouth.

“You wanted to go to the palace,” Madame Obi said, voice sugar over ground glass. “Go, then. Let us see if princes love plucked chickens.”

Amara did not look at her. There had been a time for looking—when Madame Obi arrived with a quick smile and a daughter named Adiza who courtesied with the eagerness of a child who knows the sun has moved to a different sky. There had been months of braided hair and shared soup and learning new names for old chores; then there had been the first sharpness (“you misplace too many things, daughter”), then small thefts only noticed when you reached for them, then long lists of tasks that unrolled across the red earth like snakes.

Her father had watched and said little, a man who stitched his grief to his silence after his first wife was returned to the ground. In the evenings he sat with a calabash of palm wine, eyes on the dust where stars should be. “You must endure,” he had said to Amara once, stroking the back of her hand as if smoothing a crease. “It is what is asked of women.” As if endurance were a broom you could lean back in a corner when your wrists tired.

She tied the last knot and walked.

The road to the river was a ribbon of red earth bordered by cassava and gossip. She passed the market women setting up their wares under umbrellas that had seen better rains; she passed the blind potter tapping his way to his corner; she passed the old man who made flutes and was teaching a monkey to dance. Each mouth opened to say something, then closed again because grief recognizes itself and makes room.

Beyond the yam fields, past the palm trees that whispered like old men remembering girls with legs like drumsticks and laughter like rain, stood a hut that had been there before memory decided to keep minutes. The roof was thatched with stubbornness; smoke curled from a hole in its middle like a gray snake. The woman inside was called Mama Nkechi by some, Mama Nchi by others, Witch by those who hadn’t yet needed anything of her and Healer by those who had survived themselves. She opened the door before Amara knocked. She always did.

“They cut your hair,” Mama said, her eyes two moons that did not miss eclipses.

Amara knelt on the threshold and placed her palms on the warm earth like a penitent apprentice. “They cut what the world wanted first.”

Mama touched the scarf. “Mane is not roar.”

She led the girl in. The air smelled of woodsmoke and herbs and something older, the sweetness of things fermented into wisdom. Chickens pecked outside the door. A goatskin drum leaned against a wall. Mama sat Amara on a low stool and unwrapped her head as if unwrapping a gift from a stubborn god. She did not flinch at the bald patches or the uneven tufts; she did not click her tongue with pity; she did not say “what a shame.” She dipped her fingers into palm oil and smoothed it across the girl’s scalp, feeling for heat, for shame lodged like a thorn beneath the skin.

“When the lioness walks into the forest,” she said conversationally, fingers moving like old music, “the trees do not ask her about her hair. They part because they feel her power.”

She reached for cowries polished thin by years of being exchanged for salt, for fish, for the right to cross someone’s land without becoming a story. She reached for thread dyed with leaves that had known grief and survived it. She braided. Not pretty, not intricate—every braid tight as defiance, every row a path that led from a beginning to a decision. She wove in beads—not gold, but wood and bone and shell—and when she finished she untied her wrapper at the waist and tore a strip from its edge, threading it through the braids like a pathway toward the sky.

Mama handed Amara a small mirror. The girl lifted it, found her face, and exhaled a sound that had been waiting at the door of her throat. This was not what the villagers had named beautiful. This was not waterfalls and combs and girls stepping on one another to be the first to touch hair and claim luck. This was architecture. This was a crown built from ruin.

Mama’s hand was on her shoulder. “They tried to humble you with shame,” she said, voice a clay pot cooling in the shade after being shaped in fire. “But shame is afraid of women who rise. Now go wash your feet and your fear. There is a place where your name will be said correctly.”

The royal gong had reached Umulechi the day before like thunder that carried invitations. “By command of Prince Ikenna of Enugu,” the messenger had intoned from the back of a long-suffering horse, “a festival will be held at the palace to celebrate the naming of the future queen. Let every maiden of age come and stand and be seen.” Mothers had flung open boxes of cloth that had been folded since their own girls had been girls. The beadmaker had not slept. The girls had giggled and practiced smiles that said I am shy and owning the world.

By evening the palace was a body beating time. Gold clung to carved pillars like a second skin. Lanterns swung from the arms of acacias, their light catching the dust and turning it into confetti. Drummers made the floor a pulse. Somewhere behind a carved screen, old men argued about bloodlines while drinking palm wine as if it had always been tradition and never preference.

Amara arrived barefoot.

She wore ash-colored cloth that fell in a river around her waist, the kind of dress you can dance and sweep in. Her crown was a geometry of tight cornrows and beads that made their own music when she moved. The laughter began at the edges and moved inward like ants finding sugar. “Who let her in,” someone tsked, sweet poison rolled in leaves. “She must be lost,” someone else smirked. A noble girl, sleek as a cat in silk, raised her voice just loud enough: “Perhaps she cut her hair for attention. There is a sickness—perhaps it is that.”

Madame Obi stood in the shadow of a carved pillar with her daughter at her shoulder, triumphant and anxious, the way people stand when they think they have won and fear the god who might be watching.

Amara felt the words brush her skin and fall like cheap beads. Shame wanted to take her hand. She refused it. She stood with her head high and her breath steady the way women stand when they have scrubbed floors until their hands fell asleep and their dreams kept their eyes open.

At the top of the staircase the prince stopped being bored.

Ikenna had been cataloguing beauty for hours. He knew how lace sat on the shoulders of girls, how beads liked to arrange themselves in patterns that said I have eaten and will eat again. He had learned what the elders wanted him to learn—the lineage histories, the names of a hundred families whose ancestors had given goats on a day when a god had been thirsty. He had smiled and bowed; he had danced with girls whose wrists smelled of fresh kola. And then a girl stood at the bottom of his stairs with a head that had been made into a weapon and a body that did not apologize for having survived.

He did not say “who is she.” Princes do not ask obvious questions when their blood has already answered. He stepped forward and his voice cut across the marble like judgment and grace: “I disagree.”

The hall obeyed his silence. Even the unrepentant drumline paused to see who had dared to object to anything in a room where gold was the last word. Ikenna descended the steps and the echoes counted his steps like witnesses sworn to tell the whole truth. “She is the most beautiful woman in this room,” he said, and did not blink when an aunt whispered too loudly. “Not because of her dress, not because of her hair—because she walked in anyway.”

He stopped before her and opened his palm. “May I have this dance?” he asked, knowing that asking is a power and accepting is another. Amara did not answer at once. She looked across the hall and found a pair of eyes in shadow that had once measured a child and found her too much. Madame Obi’s face had rearranged itself into the shape of a shrine that has not been visited in years—emptiness and dust and the sound of old prayers that do not fit new mouths.

Amara turned back to the prince and let her mouth find a curve. “Yes,” she said, as if agreeing to something she had already agreed to the night her mother wrapped her head for the first time and said remember.

They danced the way people dance who have survived storms alone and find that the floor is not a forest and the music is not the rain and their bodies can belong to a joy that is not borrowed. The beads in Amara’s hair made their own rhythm under the drums. When they turned, her bare feet placed unashamed steps on marble that had only known shoes. It became difficult, watching them, to remember what life had been before this moment. Patterns rearranged themselves in the heads of women in that room, including those who had once laughed because laughter is the hand closest to the mouth when envy catches your throat.

Festivals end and begin the same night. This one ended with a proclamation that raised dust from the feet of the women who ran to carry it outward: “By command of Prince Ikenna of Enugu, the future queen shall be Amara of Umulechi.” The marketplace closed for dancing. Men beat drums until the goats complained and then beat them because the goats were old and did not know what they were missing.

Madame Obi did not come to market the next day. By the time gossip made it to her gate wrapped in leaves, the house was empty. She left noiselessly, the way shame leaves when it refuses to learn another shape.

Amara did not sleep much. Even queens must put their head somewhere when the drums quiet. She sat outside the hut of Mama Nkechi with her head on the elder’s knee and her feet in sand dampened by dawn. “I did not come to thank you,” she said, the sky peach and plum above the palms. “I came to ask how to carry this without my neck breaking.”

Mama’s fingers found the beads again. “You will carry it the way women carry water from the river,” she said. “Straight of back, steady of step, mind on the path and on the mouth of the calabash. When it spills, you do not drink the mud, you go back to the river. When a child begs for a sip before you reach home, you give and you drink last. When the load is too heavy, you ask another woman to walk with you.”

Amara nodded. She had come to the river and would carry the water, but she resolved something else under that blue dawn: her reign would not be a dress. It would be hands and the people they held.

Part Two

There is a kind of silence that arrives after a coronation. Not quiet—nothing quiet lives in a palace where advisors are born with opinions and cousins multiply like yams in good soil—but a pause in the air, right before the new thing speaks its first word. In that silence, Amara took stock.

She walked the corridors in bare feet the first morning because marble has a memory and she wanted it to remember. Servants lifted their eyes and lowered them again as quickly, not out of fear but because love is shy when it is new. She walked beyond the carved doors and gilded verandas and into the kitchens where smoke thanked ceiling beams for keeping it company and women with scarred hands fed a kingdom while the kingdom noticed its own reflection and adjusted its head tie. She walked into the courtyard where guards practiced what to do with their spears besides lean on them. She walked into the stables, into the cloth rooms, into the little dark corners where old people who had been servants longer than kings remembered everything and kept it like coins.

“You are queen,” one of the ancient maids whispered, as if that were a secret that needed to be handled carefully. “Yes,” Amara said, and then, because she had learned the power of adding “and” to “yes,” added, “and a woman. The first is a crown I can remove; the second is a skin. Show me where the roof leaks.”

In every place she entered, she asked two questions: What is broken? What is beautiful? She kept a small book tucked into her wrapper and wrote down the answers even when they made her bite her lip until it dampened. In that book lived a list of things that needed mending: the flood channel on the east wall that overflowed whenever the rains were too eager; the rule that allowed men to bring cases before the council while women brought them to kitchen tables; the levy on market women that had been “temporary” for seven years.

“This tax,” she said in the fifth council meeting of her reign, “will end today. If this council chooses blood, they will bleed. If it chooses justice, the market will feed them.”

Men whose wives had whispered while kneading fufu exchanged glances and weighed their stomachs against their fear. “We must consider the treasury,” the oldest among them said, skin papered with years. “We must consider the women who keep it full,” she said, “and the children who need shoes.”

The levy died without dying dramatically. Some things ought to go quietly to their graves.

She visited Mama Nkechi every seventh day and never wore the same wrapper. It wasn’t vanity; it was a ritual that kept her tethered to the women who saw cloth the way men saw land—an investment, a possibility, a story you tie around your waist. They sat under the almond tree with calabashes of kunu and watched young girls in braids chase chickens who had made rash career choices.

“Queenship is not witchcraft,” Mama said one afternoon. “It is arithmetic. You add women to decisions. You subtract impossible demands. You divide work fairly. You multiply joy where you find it and sometimes where you don’t.”

Amara’s book filled the way a pot fills when the lid is left off and rain decides it loves you. School stipends for children whose mothers were widows. A law that said stepchildren had the right to eat what other children ate. A hair ordinance (they laughed when she wrote the first draft; they did not laugh when she finished) that forbade employers from docking girls’ wages for cutting their hair in mourning because hair is a story for women and men are guests in that house.

Within the palace, resistance rose where water used to be. “It was not done this way before,” someone would say, and she would smile the way women smile when they are about to do something and hate being told they cannot. “Everything was not done this way before,” she would reply, and let it be a proverb.

She instituted a Day of Rest for Servants. The palace stuttered, then learned to cook for itself for twenty-four hours—princes stirring pots, councilors dropping plantain into oil and discovering humility. At the end of the first Day of Rest the kitchens returned to find bouquets of burnt stew and flowers on their tables.

Amara knew how to win, and not only theatrically.

In the fourth month of her reign, the past knocked on a side gate and did not know whether to run after knocking. A palace girl found Madame Obi sitting on a stool under the bougainvillea, her wrapper faded to the color of other people’s memories, hands clenched in her lap because they had learned to make fists too easily. The girl came to Amara with her mouth full of bees.

“Bring her,” Amara said.

They led Madame Obi through a hallway that had never been designed for a woman whose feet remembered market dust. The palace walls narrowed when you remembered you had been unhappy in a small house and decided to be unhappy in a larger one.

They stopped in a room where light repeated itself in mirrors and a jar of kola sat between chairs like a mediator. Amara entered in a plain wrapper with her head unwrapped. The braids had grown in thick as rivers; beads clicked softly, a whisper that had learned to make the air lean in.

“Sit,” Amara said, voice as neutral as water, dangerous in drought and in flood.

Madame Obi sat because she had run out of stations to skip. A guard placed a calabash of water between them and left as if innocence could be restored simply by having witnesses exit.

“The goats did not eat your tongue,” Amara said when the silence had finished searching both faces. “Speak.”

Madame Obi stared at her hands. “The first time my husband looked at you,” she began in a voice that came from a throat that had been a bottleneck too long, “he used the same eyes he used to use when he looked at my daughter. Not because he loved you less, because beauty takes what is in men and returns it as madness. The village called your name like prayer. I counted your beads and counted the days until my own name became a story. I cut you because I wanted to wound the god that kept choosing you.”

She lifted her eyes for the first time, and in them was a girl who had been praised only when praise was cheap and withheld when praise was expensive. “I am sorry,” she said, the words falling clumsy from a mouth that did not practice them. “I ask for forgiveness, not because queens love to forgive and place crowns on their heads for doing it, but because I do not want to die in a house where even the chairs remember me as a villain.”

Amara considered this woman, this old general of envy, this mother whose daughter had been asked to fight a girl because adults had more to fear. She could have summoned guards and laws and punishments. The law was hers to bend and break. She could have made a theater of justice; the village would have come in their wrappers and returned with stories to feed a week. Instead she drew a line with her finger on the table between them.

“Men measure justice by weight,” she said. “Women sometimes measure it by distance traveled. Here is what will happen. You will go back to your village. You will start a school in your courtyard. You will teach girls what to do with hair and envy. You will cut your own hair. Not to be punished—so every morning in the mirror you will remember that crowns are heavy and sometimes better woven with hands that have learned gentleness. You will not call me. When I hear three good things about you from mouths that have no reason to lie, I will come. If I hear three bad things, I will come, too.”

Madame Obi’s mouth trembled around pride and relief until relief won. She stood and reached for the calabash. “Water?”

“Water,” Amara said, and they drank.

That evening, when the palace women gathered under the almond tree to gossip while their hands shelled egusi, the story had already begun to run. “She forgave,” someone said, not with admiration but with the weariness of a person asked to lift something heavy while men watch. “She did not forgive,” someone else corrected. “She made a road and handed someone a load. That is different.”

The work multiplied and so did joy.

Prince Ikenna watched her as a man watches rain arrive after he has convinced himself he can live without it. He was not a storybook prince, not a man who believed his worth was measured by his shadow’s length. He learned to stand back in rooms where she stood forward. He learned to say “We will do as the queen says” without biting the pronoun. He learned to hold babies like they were the nation. He learned to ask his sister for advice and mean it.

They quarreled. She was not a saint; he was not a god. They fought over a land dispute that had swallowed five cousins; they fought over a cousin who had used the treasury like a bamboo that believes it is a river; they fought over a chair someone had moved in the council room because sometimes power arrives in small tantrums. Once he raised his voice and apologized before the echo died; once she walked out and returned with palm wine because nothing that is supposed to last is supposed to be without ceremony.

The people began to say “Amara did this” the way people say seasons’ names. The market tax gone. The school in the slum behind the third gate built with stones that had been bought with money that had previously bought wine. The law that said stepchildren could eat at their stepfather’s table or he would not eat in public without shame. The hair school in the east courtyard—the room with the low round stools and mirrors that did not magnify flaws but made faces look like faces.

Every month Amara opened the doors of that school and sat on a stool while girls with scarred scalps and shy mouths learned the mathematics of their own crowns. “If someone cuts it, it is not the end,” she would say, fingers moving in a rhythm older than mourning. “We will braid truth into it until it becomes a story you tell, not one that keeps telling you.”

Her stepmother arrived quietly one morning and sat in the back and cried without making a mess, then picked up thread and learned to part hair without tugging too hard. After three months a girl from her village came and said she had started a courtyard class. After six months an almond tree in that courtyard wore ribbons like prayers. When Amara went to see, the women ululated, shame having learned how to sing another song.

In the second year of her reign a drought arrived and threatened to teach everyone humility with a dry hand. The river shrank like a wish someone had not watered. Men argued about gods. Amara gathered the women farmers and asked what the ground wanted. They showed her a place where a stream could be cut from a reluctant tributary; she brought the men and the spades and the promise of goats roasted when the work was done. She moved grain from the palace storehouses into the village stores at night so men could pretend in daylight that it had been their idea to feed strangers. The drought learned its place and the rain returned with apologies caught between drops.

When the rains broke over Umulechi and old women stood in their doorways and stuck out their tongues like children to catch water the way it used to taste before the city smelled its own perfume and believed it, Amara stood under the downpour and lifted her face. The beads in her braids were polished with rain. The scar where Madame Obi’s blade had come too close to the space that held her fire glowed like an old lesson.

“I send a decree,” she told the scribe with the fierce eyebrows who always asked impertinent questions like “Will you be remembered?” “And I want it to be delivered loud.”

He dipped his pen. “Speak, my queen.”

“From this day,” she said, “any woman whose hair is shorn as punishment or spite will be brought to the palace school, fed, and taught. Any person who laughs at her will carry water from the market to the palace gate until their back learns manners. Any person who orders the cutting will cut fabric for free in the market until their hands learn compassion. Hair is not a foundation for crowns. The heart is.”

The scribe looked up, eyes bright. “I will add flourish.”

“Do not,” she said, and went to sit with the women who were weaving mats because kingship is for carpets and queenship is for the rooms where people spill palm oil and no one makes a scene.

On the anniversary of the night a pair of old iron scissors tried to teach the moon something new about shadows, the palace held a feast that did not include speeches. They opened the gates to the market women and the goat herders and the boy who had learned to play flute with the monkey. Men with titles sat on the low stools and learned that rice is eaten with hands. Girls with braids of ten thousand designs sat together and traded hair beads like gifts. Madame Obi—hair short and neat, hands busy with thread—arrived with a basket of buns and left with a ribbon tied to her wrist by a girl she had not remembered to love when the world was asking her to choose.

Later, when the lanterns hung low and most of the kingdom yawned, Amara and Ikenna slipped away to the east courtyard. The almond tree made confetti of moonlight. The hair school’s mirrors leaned against the wall like women waiting for the music to start. Amara removed her head wrap and shook out her braids. They had grown heavy and were threaded with cowries polished by thumbprints.

He touched one bead. “When I speak to a room full of men who think they made the world,” he said, smiling without apology, “I think of this courtyard and it makes my voice correct itself.”

She leaned against him. “When I braid hair,” she said, “sometimes I forget you are a prince.”

“Good,” he replied. “That is the crown I’m least interested in.”

They laughed quietly for the sake of the almond tree and the wall that had learned to keep secrets. Then they danced—no drums, no audience—barefoot on warm stone, moving slowly like people who have already done the fast things and have chosen, stubbornly, to keep living.

In a small room at the far edge of the compound—a room that had once been storage for broken chairs and now was a library where women came to borrow paperbacks about other lives—Amara kept a box. In it lay a pair of old iron scissors, wrapped in cloth, not displayed. She had bought them from the blacksmith who bought everything metal and made it useful again. Sometimes she would take out the scissors and hold them the way fishermen hold hooks and tailors hold needles—tools that have made and unmade the world. She never cut. She simply remembered, then put them away because remembering is a door you should close when you leave if you want to sleep.

Years later, girls in Umulechi would stand before mirrors and tie head wraps and tell a joke that made them bold: When a lioness walks into the forest, do the trees ask about her hair? The joke made them brave the way proverbs do when they have learned to laugh at themselves. They would say “Amara” the way people say “rainy season”—with gratitude and a little relief.

And if someone asked—in the market, at a wedding, under the almond tree—how did the queen become a queen without braids long enough to sweep floors, the women would shrug in the direction of the palace and say, “They cut her hair to make her ugly. The gods only laughed and tightened her crown.”

In the end, Madame Obi did not return to the palace to ask for favors. She lived a long time teaching girls to part hair gently and women to measure the cost of envy before borrowing it. When she died, women came to the courtyard and tied ribbons to the almond tree, not because she had been good but because she had learned good. Sometimes this is all heaven asks.

Mama Nkechi went to the part of the world where elders go when they have finished stirring soup and sense that the young have learned how to lift the spoon. The palace built her hut a new roof before she left, not because she needed it but because love is also carpentry. On the day she died, the goats did not bleat. The wind carried her last breath across the yam fields. The almond tree bowed. Amara added a note to her small book: Remember to weep like rain. Remember to plant where tears fall.

And when Amara’s daughter, years later, asked her mother to plait her hair for a dance she had been invited to by a boy whose father cleared throats for a living and had finally learned to eat in the kitchen with a straight back, Amara sat the girl between her knees and said, “Listen,” the way mothers say when stories are about to begin. “Once a woman cut my hair to make me small. I learned I am not my hair. But that day taught me the kind of queen I will be.”

Her fingers moved—the old rhythm, the tight rows, the beads that clicked like the softest thunder. She did not stop when she reached the scar. She braided over it with the gentleness of a woman who knows some crowns grow from wounds.

Outside, the palace hummed like a hive where the bees had decided to be generous with their honey. Inside, a queen braided a child’s hair and thought, not of everything she had endured, but of everything she had built. The scissors slept in their cloth. The almond tree waved a branch like a fan to cool the night. Somewhere in the dark a drum began. And the crown, far removed from gold, sat where it had always belonged—steady, invisible, impossible to steal.

END!

News

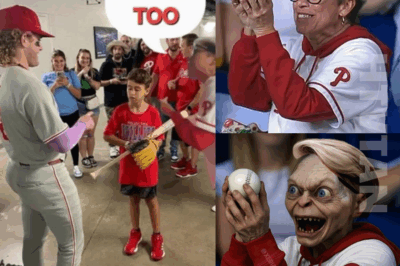

Phillies ‘Karen’ is facing the WORST backlash ever fans are NOT holding back…Should this be stopped?

Phillies “Karen” Faces Brutal Fallout: Viral Shame, Job Rumors, and a Stadium Exit From Outrage to Redemption: The Aftermath…

My Mother Told Me I Couldn’t Afford Dad’s Birthday Dinner — Then The Staff Greeted Me As The Owner.. ch2

My Mother Told Me I Couldn’t Afford Dad’s Birthday Dinner — Then The Staff Greeted Me As The Owner …

She Was Sitting Alone at the Wedding—Until a Stranger Whispered, “Pretend You’re With Me.” CH2

She Was Sitting Alone at the Wedding—Until a Stranger Whispered, “Pretend You’re With Me.” Part One Crystal chandeliers cast…

My Parents Sold My Dream Car For My Sister — They Regretted It When I Made Her Repay Every Cent. ch2

My Parents Sold My Dream Car For My Sister — They Regretted It When I Made Her Repay Every Cent…

Billionaire Lady Sees A Boy Begging In The Rain With Twin Babies, What She Discovered Made Her Cry. ch2

Billionaire Lady Sees a Boy Begging in the Rain With Twin Babies, What She Discovered Made Her Cry Part…

“If You Can Dance This Waltz, I’ll Adopt You”—Millionaire Mocks Black Girl, but Then… ch2

“If You Can Dance This Waltz, I’ll Adopt You”—Millionaire Mocks Black Girl, but Then… Part One “If you can…

End of content

No more pages to load