Stepchildren told me to know my place in their house, so I knew exactly where I belonged, gone, along with my financial contributions.

Part One

The first thing I learned about blending a family is that you can sand every sharp corner and still cut yourself on the edges you didn’t see.

I met Rebecca at a service call I wasn’t supposed to take.

Her building’s breaker panel was older than me and the building manager had called our shop. I was supposed to be across town, but Benny’s kid had the flu and I picked up his ticket. When I knocked on the door, a woman with paint on her elbows and a pencil tucked behind one ear opened it like she’d been waiting specifically for me and said, “You look like someone who knows the difference between a neutral and a ground.”

I did. She knew the difference between a real laugh and a polite one, and she gave me the first one three times before I left. She said she was a project manager for an events company and somewhere between replacing a bus bar and explaining the difference between tripping and arcing, I agreed to coffee. The next Sunday, I watched her hand out library books to three kids as if she were dealing cards in Vegas—confident, quick, practiced. Tyler, 14, who wore a baseball cap to the left insistently; Ashley, 12, with glitter on her nails and a point to prove; Jordan, 10, the kind of kid who looks at everything like it might start talking.

I was 36 then. The apartment I rented was clean because I cleaned it, quiet because I lived alone, and orderly because no one else touched my tools. I had a plan: work, save, buy a little two-bedroom somewhere with trees. Then I fell in love with three people I didn’t know how to price into the plan and one person who made me rewrite the whole thing.

We moved after eight months. It felt like a romantic gesture and a practical one—I had good credit and savings for a down payment; she had furniture with more character than structure and three kids who shared a room where the wallpaper peeled itself off the wall. The house I found wasn’t fancy, but it was solid—the kind with hardwood floors that had already forgiven a few lives and a basement that smelled like it had opinions. Four bedrooms. Decent schools. A backyard with a maple old enough to shade the mistakes.

Our deal was simple. I’d cover the mortgage and the big things—roof, HVAC, everything you don’t post about on social media. She’d cover groceries, the little things, and the emotional glue between four people who didn’t know where to sit yet. We were a team. She said it and I believed her.

The first year felt like victory disguised as routine. I worked and came home tired in the way that feels decent. They learned quickly that a man who knows circuit load calculations also knows how to make a grilled cheese that’s hot all the way through. I installed a secondhand surround system in the basement, dragged in a couch that someone rich and bored had left on a curb two streets over, and watched Tyler’s shoulders drop the first time his friends came over and he didn’t feel the need to apologize for anything. Ashley wanted to try the expensive dance academy; I found the money and the schedule. Jordan liked to fall asleep reading on the floor at the foot of our bed; I carried her back to her room and pretended my back didn’t pop.

I learned the location of every teacher’s classroom and which shortcuts around town were faster by five minutes but only if you made the light at Greer. I put a bench next to the door specifically for the purpose of lost shoes and I never moved it again. I hung a pegboard in the garage with outlines for hammers and wrenches and tried to believe that if everything had a place, that meant I did, too.

It was small things at first, the kind of weather changes you could explain away as seasonal. Tyler stopped saying thanks. Ashley started clarifying that she’d already asked her dad about anything expensive, so “we should probably just wait.” Jordan, who had called me “Kev” like it was a nickname on purpose, started saying “Kevin” with the careful diction of a kid calling a teacher they don’t particularly like. Rebecca told me boundaries were being tested, that divorce makes kids weird for a while, that Derek—her ex—said things that didn’t help. I agreed because you do that when you love someone and because there’s no manual for being a step-anything.

Year three tasted different. I learned what it felt like to be the person who sits in the bleachers with a seat cushion and a water bottle and a voice that knows how to cheer on the third down and still not be the person Tyler looked for in the stands. He’d pose with Rebecca for photos under the glow of a stadium light and I would be the one behind the camera saying “one more” while sweat cooled down my back under a hoodie. He had a flat tire on a Tuesday. I fixed it in our driveway with my own jack and he posted a story that said “changing a tire like a boss” with his hat backward and chose a song and never mentioned me. It was fine. Not everything has to be gratitude. But after enough invisibles pile up, you trip on them.

I did what I do when a breaker panel starts buzzing. I listened. I tightened what I could. I told myself hums are normal until they aren’t.

When Rebecca and I got married in a little ceremony behind the maple with a rented arch and a playlist and a few folding chairs borrowed from her cousin’s church, I asked Tyler to stand with me. He said yes in the way people agree to spoon coleslaw onto their plates at a party. Ashley wore a dress that cost an entire week’s paycheck, and I told her she looked like magic because she did. Jordan threw flower petals with every bit of conviction her ten-year-old wrists could muster.

During the reception, I heard Ashley tell her cousin, “Mom married Kevin. He pays for everything, so it makes sense.” It was one sentence. Not untrue. Also not a sentence anyone hopes to be their headline. I swallowed it with a piece of cake.

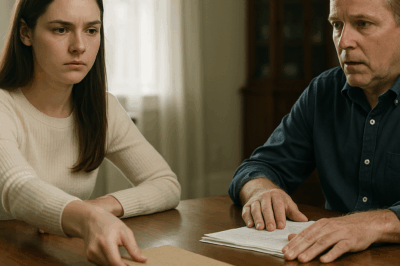

A month later, I took out a piece of paper and wrote a list called Family Rules in block letters. Respect. Try. No phones at dinner. Ask before taking. Rebecca watched me ink the lines and said nothing. We called a meeting at the dining table because families that have meetings are the kind of families that work, I thought. I started to talk about how blended doesn’t mean divided, how every house needs a rulebook, and Tyler cut me off without looking up from his phone.

“Dude,” he said. “Just because you married our mom doesn’t mean you’re our dad. You need to understand that.”

Ashley nodded without adding words; it was more efficient. Jordan, my Jordan, the one who trusted me with fractions and dance recitals and a panic attack that had come out of nowhere on a Tuesday in March, said, “You’re nice and everything, but you’re not really family. You’re more like Mom’s helper.”

Rebecca did not correct them. She pressed her lips together and looked at a water ring on the table and waited for the moment to pass.

That night I fixed the kitchen cabinet door that had been hanging crooked for two years and slept three hours, all of it shallow.

Three months later, the day I knew I was done began with a job I shouldn’t have finished early and ended with me standing in my own hallway hearing my own name the way you hear about someone famous: not as a person but as a concept.

Tyler: “Kevin thinks he’s our dad or something. It’s honestly embarrassing.”

Ashley: “I know, right? Like, dude, you’re not special. You just married our mom.”

Jordan: “He acts like he owns this house or something. Like we should be grateful he exists.”

Tyler: “He needs to know his place. This is our house, our family.”

Ashley: “Exactly. He’s lucky Mom lets him stick around. Most divorced moms wouldn’t put up with some random guy trying to play daddy.”

Jordan: “He’s so desperate for us to like him. It’s actually pathetic.”

They weren’t trying to be cruel. They were being teenagers with an audience and a script they’d been handed by an absence that kept calling itself father. It still cut clean through.

I had time to walk back outside and be a person alone in a truck, which is one of the few places men are allowed to think. I thought for two hours. I came back in and asked Tyler about his day and asked Ashley if she’d decided on the leotard with the copper mesh or the one with the cut-out and helped Jordan find the page in her math book with the problems she pretended not to understand. Then I went into my office and opened Quicken.

I am an electrician. Numbers are the way I keep metal honest. The way to keep people honest is to write them down.

I pulled statements. Mortgage. Utilities. Phone plan. Car insurance on a car I did not drive. Groceries I did not eat because teenagers are locusts and I wake up at 5:45 and eat toast. Dance tuition. Football fees. Tutoring. Streaming. Gas. School clothes. Shoes they wore for three months and declared “dead.” I printed every large receipt because paper makes the truth heavy enough to feel. $400,000 over seven years. Not counting the down payment or what it costs a man to think about other people’s schedules more than his own.

I started recording conversations. Not to catch them. To stop myself from thinking later that marriage had made me a ghost.

A month after the hallway—that day—the three of them told me to know my place at dinner. It was a Tuesday because there are always enough Tuesdays to hold a story together. Rebecca was working late. I bought their favorite takeout because I know everyone in that house by their orders. Tyler accused me of putting “dad rules” on him. Ashley said I didn’t get to “make the vibe weird.” Jordan said, “This isn’t even your house. It’s ours. You need to remember your place.”

I put my fork down carefully so the metal wouldn’t clang and startle anyone.

“You’re right,” I said. “I do need to know my place.”

I stood up, walked into my office, and found the binders I had made because electricians believe in redundancy.

When Rebecca came home, I slid the binders across the table like we were two bankers at a loan origination meeting. I played the recording of three voices I recognized better than my own.

She cried in the way women close to the edge cry—no lips, just water. “They’re just kids. Teenagers. They don’t mean it.”

“They do,” I said. “And that’s okay. Kids are allowed to tell you who you are to them. I’m allowed to stop paying for a version of myself I can’t be.”

I called a realtor the next morning. My lawyer filed the papers that afternoon. Rebecca watched me like she watches a YouTube video on fixing a dishwasher—like she wants to be the kind of person who takes responsibility for a mess but isn’t sure which screws to keep track of. I told her she could buy me out or sell the house and split what the state says is fair. She asked for time. I gave her fifteen days because grace isn’t an infinite resource and I had given eighteen-year-old Kevin’s belief in it to thirty-year-old kids who didn’t know how much they were getting.

The first thing they noticed was the Wi-Fi.

The router blinked a steady blue like it was bored with all of us. I unplugged it, not out of spite, but out of math. Tyler stood over the bare shelf with a look people reserve for caskets.

“This is ridiculous,” he said.

“A little,” I said. “But so were the last seven years. Pick which ridiculous you want to be in charge of.”

Ashley’s dance tuition bounced a week later because autopay works both ways. Jordan’s streaming service asked her to re-enter a password because the family plan was no longer a family. Tyler’s car insurance lapsed and I declined to call as an adult on his behalf. Derek said he’d take care of it and then didn’t. People who say “I got you” rarely do. That’s why people like me exist.

For three days, Rebecca sent messages that sounded like apologies but were actually requests. “We need to talk.” “The kids are upset.” “Could you at least keep the phones on?” “Derek isn’t picking up.” “I know you’re mad.”

“I’m not mad,” I wrote back. “I’m done.”

It took two months to sell the house because it always takes two months to sell a house unless you’re a legend in a small town talking about it on TikTok. We split exactly what we were supposed to split. I moved into a place over a muffler shop with good bones and decent light and a landlord who fixes things because he knows I can tell when he’s lying. Rebecca and the kids moved in with her sister because life without scaffolding is heavy if you can’t afford your own.

They wrote letters because people raised in houses with bulletin boards know that paper is a faster apology than words to your face. Tyler said he “didn’t realize.” Ashley said she “took me for granted.” Jordan drew a picture of me fixing a lamp because kids think love looks like labor when it’s done quietly. I put the letters in a drawer with bolts and nails and fuses because you don’t throw away things that might be useful again even if you can’t fit them into your circuits at the moment.

Six months later, Rebecca wrote to say Derek had “become less available.” That is one way to say a man hides in the word father when it’s convenient. Tyler was failing out. Ashley had quit dance because working the late shift makes pliés impractical. Jordan was crying at night, which is what happens when the adults who taught you not to listen stop talking.

“They need stability,” Rebecca wrote. “They need you.”

“They needed me when I was there,” I typed. Then I turned my phone face down and sat in the quiet so my heart could stop trying to be a boy scout with a pocket knife and too much rope.

A year later, I met Sarah because I fixed her porch light and she gave me lemonade with real sugar in it and asked me what I wanted instead of telling me who I should be. She teaches third graders and laughs at my bad jokes as if I’m not testing her. She knows how to make scrambled eggs the way my mother did—almost dry, somehow still soft. She looks at me like the first person to ever not take her for granted, which is not something any human being can own about another, but it sure is nice to borrow.

When Rebecca and I see each other now—at the grocery store, at the hardware store when she’s buying picture hooks she won’t use correctly—we nod because that is what you do when you are two people who don’t have anything left to apologize or gloat about. The kids became themselves without me, which is an ugly sentence to type when you’re a man who learned how to be useful by putting other people’s names first. Tyler did not finish school because the lure of a paycheck at nineteen is more persuasive than a forty-year-old man saying “later.” Ashley found out that glitter does not adhere to bills the way it does to eyelids. Jordan still writes me letters she folds into halves and halves again until they are so heavy with hope they might break the mailbox.

I don’t answer every envelope. If you think that’s cruel, you must not have done the math on what it costs to keep a generator running for a house that refuses to admit the power is out.

But the thing about telling a story is that once you start, it keeps walking.

Three years after I moved out, I got a call from a number I didn’t recognize at 11:43 p.m. I don’t answer unknown numbers at midnight because that’s a boundary my therapist friend told me to have, except electricians answer phone calls at midnight because it’s always a breaker somewhere and that is how my mortgage gets paid.

“Hello?”

It was Jordan, except she wasn’t fourteen anymore.

“Kevin?” she said. “Don’t hang up. I know you probably—please.”

The words fell over each other the way fear and responsibility do when they don’t match up yet. There was a smell behind her voice I knew too well: ozone and hot dust.

“Where are you?” I asked. She gave me an address halfway across town. “What’s wrong?”

“There was a pop,” she said. “And then we lost power in the kitchen and it smells weird and…” She started crying which I did not take personally because alarms are loud.

“Go outside,” I said. “Don’t touch the panel. Don’t flip anything. I’ll be there in twenty.”

I pulled pants over boxers and grabbed a shirt and my toolbox and keys. I did not think about the story I was about to tell Sarah about why I left. I didn’t need to. Sarah, half asleep on the couch, told me to go and to text her if I needed help and to remember to breathe through my mouth if there was smoke.

When I pulled up, Jordan was on the curb with two little boys pressed under her arms like she’d grown extra bones to hold them. Ashley came out of the dark hallway behind them with her hair up in a knot and a look in her eyes like she had found the edge of the map. The kitchen stank. The outlet behind the fridge had black around it like eyeliner gone wrong.

“Backstabbed outlets,” I said to no one in particular, because that is the kind of thing that makes me angrier than people think I can be.

“It just—” Ashley started.

“I know,” I said. “Let me shut it down so it stops telling you it’s fine.”

I killed the main, opened the panel, and felt the heat pulsing back at me. Someone had double-lugged a breaker because people assume metal is more forgiving than wood. I rerouted. I changed what needed changing. There was a splice behind the drywall that should make whoever did it feel shame in their bones. It took an hour with my headlamp and my hands and a few words no one’s mother should have to hear.

When I was done, the fridge hummed again with the steady arrogance refrigerators have. The kitchen lights did not flicker. I washed my hands in their sink and dried them on a dish towel that said you are here with a dot to indicate now.

“Thank you,” Ashley said. There was something not-yet-practiced in the way she said it that made me feel both older and less alone.

“Send me a bill,” she added, like she had prepared to be a person who could afford things and was determined to try again.

I shook my head. “You can pay me by not dying,” I said. “And by not letting anyone else who doesn’t know what a neutral wire is touch your breaker panel. Ever.”

She laughed and cried at the same time, which is a sound that makes me feel like I finally learned a chord.

On the way out, Jordan stopped me. She had grown exactly into the person you assume a kid like that might be: taller, still drawn to books, eyes that don’t blink just because your voice does. She held out an envelope.

“I wrote it two years ago,” she said. “I didn’t send it because I didn’t know if you wanted me to. I don’t even know if it makes sense anymore.”

I put it in my back pocket and told her I couldn’t promise anything and I meant it and she nodded and that is how you know someone might be okay.

At home, Sarah was asleep on the couch with a book over her face and our porch light, which I finally got around to putting on a sensor, glowing exactly the way I want to be remembered: not dramatic, not dim.

I read the letter at the kitchen table at 1:12 a.m. while the city hummed like a transformer three blocks away. Jordan had written about the day in the hallway and the song she was listening to (it always matters), about the smell of electricity that night and the quiet afterward, about how she had spent two years trying to learn the shape of an apology that wasn’t just a set of syllables. She ended with this:

If you never write back, that is okay. I told my therapist I don’t deserve your presence and she told me it’s not about what I deserve, it’s about what you choose. I hope you get to choose happy. I am trying. You did teach me things. I recognize the sound broken things make before they break.

I wrote back because a tired seventeen-year-old who can name electricity by sound is not a person I want to leave outside my porch light.

I said thank you. I said no to dinner and yes to coffee in a park during daylight with other people around because boundaries are not punishments; they are power strips that keep overloaded circuits from burning down houses. I said I would not go to football games or recitals because those times are given to me by someone else now and I won’t repay them in nostalgia. I said I would answer letters if the letters were about math or books or how to not get scammed by a mechanic. I said I would not be a father but I could be a man who shows up when wires hum wrong.

She wrote back two days later to say thank you and to ask me how to tell if an alternator is dying. I sent her a video I made in my shop with bad lighting and better information. She responded with a picture of a belt and a caption that said this? and I wrote back nope, other side. and it was the first time in eight years I didn’t feel like I had to be a boy scout and a bank and an apology and a clown all in one outfit.

Tyler wrote me from a number I didn’t have. It was one sentence: I was a dick. I did not respond because there are sentences that require more than apology to merit time. Maybe someday.

Rebecca texted me congratulations on my wedding day and Sarah took my phone and responded for me with a heart emoji because sometimes forgiveness is easier to type when it isn’t your history.

We got married under a different maple, this one in a park with a gazebo that always looks like it’s about to be in a movie but never is. Sarah wore a green dress because I like it and because white is tired. The vows were short because I’ve learned long promises are for people who haven’t had to keep them yet. We danced to the music my feet made on the grass.

After the ceremony, while we ate cake that tasted like butter without apology, an envelope appeared on our table under the edge of a napkin. No return address. Inside was a gift card to the hardware store and a note that said, Congratulations. Buy the good anchors.

—L.

I didn’t tell Sarah about it until we got home because I did not want to let a ghost stand in the same room as our dancing. When I did tell her, she said, “It takes people a long time to learn to be new.” Then she kissed my forehead and asked me if I thought the porch light needed a warmer bulb.

It did.

Part Two

The first thing I cut after I left that house was the Wi-Fi because yanking out the cord felt like yanking out a piece of myself I had sutured into their lives. The last thing I cut was the habit of apologizing before I asked for space. It took longer than copper does.

Walking away doesn’t end the story. It just changes your role in it.

I still get pulled into other people’s breakers. Sometimes literally. Sometimes a man calls because his wife is tired of a switch that sparks and I tell him my first open appointment is three days out and he says, “But what am I supposed to do?” and I say, “Turn the breaker off. Light a candle. Take her to dinner.” He sighs and tells me he will see me Tuesday because he is not that man, not yet. Sometimes a woman calls because she is tired of asking and she says she will pay whatever it costs and I say the number slowly and tell her she will not have to call me again if she listens.

I don’t do work exchanges. I don’t let people pay me in favors. I say no enough times to make my throat feel like it belongs to me.

One foggy morning two winters after Sarah and I braided our lives together, I was eating eggs and scrolling the news when I felt a tug in the part of my brain that looks for old trains and newer tracks. The headline was Local Coffee Shop Closes After 18 Years. I recognized the photo immediately. Rebecca had spent half my mortgage there in conversations I will never be invited to remember. The article quoted a city council member who said the shop “failed to innovate” because people who have never paid a barista think cappuccinos are a plot that can be outsmarted.

“That was their place,” Sarah said, reading over my shoulder. “I’m sorry.”

“It was good coffee,” I said. “They didn’t deserve the rent hike.” I sent a donation to the owners’ GoFundMe because I am a man who learned how to look for the people under the noises.

At work, I got a call from a number with a problem I suspected I could name without seeing. It was Ashley. Her voice was measured, the way a person folds a paper they have been writing on.

“I started classes,” she said. “Night ones. For HVAC. I thought you’d laugh.”

“I don’t laugh at people trying to make heat.”

She exhaled and it wasn’t a sob, which felt like progress for the both of us. “I wanted to ask about apprenticeships. I know it’s a lot to ask. I just—I like this. I’m good at it. It’s like dance, except practical.”

I wiped drywall dust off my forearm and put her on speaker so I could write down the names of two people I would trust with anyone I cared about. “You won’t work for me,” I said. “Not because I don’t want to see you. Because you will learn the old habits if you lean on me, and you need new ones. Call these two. Use my name. They’ll teach you right. It’s going to be worse than you think for the first year and better than you imagine in the fifth.”

She paused and then said, “Thank you, Kevin. For the names. For the fifth year.”

I hung up and stared at the imprint my coffee mug had left on my workbench and wondered how many kids think their house stands because walls love them when really it stands because someone checked the load calculation on the second-floor bathroom and said, “Not like that.”

On a cold Saturday in February, the door buzzer in our building hummed and I let the noise sit there to see if it would go away. Sarah was at the sink washing carrots for a soup she insists will save anyone who eats it. I wiped my hands on a towel and pushed the intercom.

“It’s me,” Jordan said. “Please don’t—if you say no, I’ll go.”

I buzzed her up. She stood in my doorway the same way she stood at the curb that night—arms crossed like she’s holding a thing still because it won’t hold itself. She had a book under one arm and a knock-off handbag she had loved into realness and the same eyes that know when an alternator is dying.

“You can come in,” I said. “Our dog is loud for ten seconds and then he remembers he’s a coward.”

She sat on the edge of our couch and let the dog sniff her shoes politely. “I came to give you this.” She handed me a stapled set of papers from a therapist with the kind of letterhead that says here is a place where we try to forgive ourselves out loud. “Eliana asked me to give it to anyone I hurt if I felt safe. You’re the only person I want to give it to.”

It was an apology written in a way teenagers rarely let themselves write. Specifics. The day, the hallway, the smell of garlic on my hands from the takeout, the weight of a word she had not meant the way it landed. It didn’t turn me into a saint or her into a villain. It didn’t add modifiers to make our history easier to say in front of strangers. It closed a circuit I had left open on purpose.

“I forgive you,” I said, because forgiveness is not a reward; it’s a release valve you open when the pressure makes your pipes talk back. “I don’t forget. That’s for fairy tales. This is for grown-ups. The day in the hallway still echoes sometimes. But I believe you meant this letter. And I believe you can be better than the house that taught you to be a consumer.”

She cried. Only a little. Then she wiped her eyes with the back of her hand and said, “I have to go. I have a calculus exam and I hate my professor and if I don’t leave now, I’ll be late.”

“Take the dog,” I said. “He likes calculus. It calms him down.”

She laughed and made a sound that belonged to both of us and then she left.

You might be waiting for the scene where Tyler shows up with a bad beard and a worse attitude and asks me to bail him out of something with money and I tell him to go to his father. That didn’t happen. He texted me once at two a.m. to say a car is easier to dent than a life and then nothing for six months. People choose how they grow. It is not always visible to the people who want to measure it.

Rebecca married a man who knows how to hold grudges gently, which is a skill the world underpays. She sent me a Christmas card the first year with no note and just names under a pre-printed script that said Joy. The second year there was a note that said I’m glad you’re happy. The third year she wrote Thank you for not hating me into a worse version of myself. Sarah stuck each one on the fridge under a magnet shaped like a lightbulb.

On my forty-fifth birthday, Sarah bought me a new toolbox even though my old one had the right dents. She knows better than to try to replace things with memory inside them. It was for the class I started teaching—the one-night-a-month basic wiring class at the community college that fills up with people who don’t want to die trying to install a ceiling fan. Ashley sat in the front row twice under a blue hoodie and did not ask me for anything other than clarity on three-way switch legs. When class ended, she wiped up her own pencil shavings from the table.

I do not live in a movie and I do not need one. I live in a small apartment with the woman I chose and a dog who thinks I should never leave the bathroom without telling him where I’m going. I visit the maple in our old backyard sometimes because I installed the swing there myself and even if the people in the house changed, the knot in that rope belongs to my hands. The new owners ripped out the pegboard I put up in the garage. It hurt in the way stubbed toes hurt—humiliating and outsized. I wrote about it in a group chat full of men who understand how tools keep us from talking about our fathers. They sent me pictures of their own scars.

A year after the day at the hallway, my phone lit up with a number I had labeled DON’T ANSWER because growth is being your own secretary. I let it go to voicemail. It was Derek. “The kids need you,” he said to my voicemail. “I’m tied up.”

I deleted it because there are men who tie themselves up and then expect you to untie them, and I am not a sailor. I texted Rebecca to tell her the call had happened, because co-parents and former halves of a good idea owe each other transparency. She wrote back “thank you” and sent a picture of Jordan holding a certificate from a scholarship fund that had paid for the first semester’s books. It was named after a woman who started an HVAC business forty years ago when men said she couldn’t hold a ladder and now employs twenty people who call her Ma’am with respect.

“Tell her congratulations,” I wrote back, and then I put my phone face down again and drank coffee that had sat too long and was worse for it.

Here is what I learned.

Love doesn’t buy you a seat at a table where people are counting chairs for someone else. Paying for things doesn’t purchase respect. Sacrifice does not generate interest unless both parties deposit into the account. Making yourself small for children teaches them that the person who saves them will never ask to be seen. The house stands because someone checks the load on the joists, not because anyone feels like it should.

You cannot stay where you are not invited and call it noble. You cannot leave where you are required and call it cruel. Boundaries are not walls; they are the instructions on the side of your breaker panel—what each switch controls, how much each circuit can hold, where to turn the power off when something smells like ozone and the dog is barking and a girl you still love calls you at 11:43 p.m.

If I had stayed, I would have taught those kids that women owe men forgiveness they don’t have to earn and men owe families money they don’t get to question and everybody owes a little piece of themselves to the lie that everyone at the table is eating the same meal. If I had stayed, I would have taught my future wife that her love is a quilt for covering my pride and my exhaustion. If I had stayed, the person who needed me most—me—would have become the kind of man who cannot fix a thing without calling it his.

You asked, “What would you have done?”

I answered by leaving. And by answering certain calls. And by not answering others. And by marrying a woman who says “buy the good anchors.” And by showing up with a toolbox when a girl I love more than language hears a smell that means danger and uses my name like a poem: Please.

There is a porch light on outside my door. It turns on by itself now, because I built it that way. It is warm in the way I remember most kindness being. If you are standing in the street tonight looking up and thinking about your place, here is what mine taught me:

Sometimes the place you belong is the first one you walk yourself to after the ones you built for other people throw you a seat at the kids’ table and call it compromise. Sometimes the place you belong is anywhere you can be held by your own choices. Sometimes the place you belong is gone—from the house, from the bills, from the title “Just Kevin.”

I am Kevin. Electrician by trade. Husband by luck. Teacher by accident. Man by decision. I knew exactly where I belonged the night three teenagers told me I didn’t: not at their table, not at their mercy, not at the end of a list of things I pay for so people can pretend I’m temporary.

I belong where boundaries hum quiet and steady like a breaker doing its job. I belong beside someone who would unplug the router for me if I forgot why I did it myself. I belong in letters that say I was wrong and kitchens where the light is warm and the switch doesn’t arc and boys become men without destroying the maps their mothers gave them.

And sometimes I belong on a curb at midnight, telling a girl on the phone to breathe; that help is on the way; that this time, the man who knows how to turn off the power also knows where to stop.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

The judge froze in court when he saw me – no one knew who I really was until… CH2

The Judge Froze in Court When He Saw Me — No One Knew Who I Really Was Until… Part…

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money’

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money,’ Brian Kilmeade passionately defended Erika Kirk on…

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent. CH2

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent Part One The rosemary lamb went…

BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions in his final statement and unexplained evidence have shocked the public: Is Robinson blaming someone else?….read more below

💥 BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions…

“I Stared At The Photo—My Son Did This?” — A Sheriff’s Father Breaks His Silence On Utah’s ALLEGED KILLER

At a $600,000 family home in Washington, Utah, a veteran lawman dialed the number no parent imagines: he turned in…

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire : Ava Raine, the daughter of Hollywood legend Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, has ignited one…

End of content

No more pages to load