“Sit Down and Be Grateful,” He Barked at Me at Christmas Dinner—Then I Put on My Uniform

When Army Lieutenant Colonel Lisa Monroe came home for the holidays, all she wanted was a peaceful Christmas dinner with her mother. Instead, she walked into a house ruled by her mom’s new controlling boyfriend, Ron — a man who mocked her military service, dismissed her identity, and thought he could dominate the dinner table.

Part 1: Home, But Not Really

The plane dropped through the clouds over Texas like it had forgotten how to land.

People around me gasped, grabbed armrests, crossed themselves. I just tightened my seatbelt and stared out over the scattered lights of Austin. After a year in a place where turbulence came with tracer fire and sirens, a little shaking at 30,000 feet barely registered.

My name is Lisa Monroe. Lieutenant Colonel, United States Army. Forty-six years old, three deployments, two divorces, zero children, and one mother who still calls me “my girl” in every voicemail.

I’d missed last Christmas. And the one before that. This year, the stars finally aligned—or at least the duty roster did. I traded an inspection trip so I could get home for a full week. No staff meetings, no secure briefings, no sand in my boots.

Just my mother’s kitchen. Cinnamon, nutmeg, her old chipped mixing bowl. That was the picture in my head as the plane’s wheels hit the runway hard enough to jolt everyone upright.

Mom texted once I landed:

can’t wait to see you

Ron will pick you up!! red truck

The double exclamation points were new. So was Ron.

I’d heard about him in fragments over patchy video calls. A nice man, she’d said. Solid. Former Marine. Helped around the house. Good with tools. “You’ll like him,” she insisted. “You’ll respect him. He served, too.”

I’d nodded for the camera, said we’d see, and changed the subject. It’s hard to picture your mother with someone new when your father’s photo still hangs in your memory wearing a 1980s mustache and a Christmas sweater.

Outside baggage claim, December air bit my cheeks with that damp Texas chill—never quite cold enough for real winter, just mean enough to make you wish you’d worn more layers. Cars streamed past, drivers scowling, carols playing from somewhere too faint to place.

Then I saw him.

Big man, barrel-chested, late fifties maybe. Red flannel tucked into khakis so sharply you could’ve cut yourself on the crease. Thick gray hair buzzed short. He leaned against a red pickup, arms crossed, scanning the crowd like he was sizing up a squad.

When his eyes found me, his mouth stretched into a grin that didn’t quite touch his eyes.

“You must be the soldier,” he said, pushing off the truck.

“Lisa,” I said, shifting my duffel higher on my shoulder and offering my hand. “Good to meet you.”

He squeezed my hand with that over-eager firmness some men think is a personality trait. Not painful, exactly, but deliberate. A pressure that said, I want you to feel this later.

“Ron Caldwell,” he said. “Marine Corps. Back in the day. Your mom’s told me all about you. Whole career in uniform, huh? Impressive.”

The word didn’t sound like praise. It sounded like a card he was laying down in a game only he knew the rules to.

“Thank you,” I said evenly. “She’s told me about you, too.”

“Yeah?” He popped the tailgate, grabbed my duffel before I could. “Hope she told you I’m the one keeping that old house from falling apart. She’d burn water if I let her near the stove.”

He laughed. Loud. Like he expected the sidewalk to laugh with him.

I didn’t.

On the drive home he talked almost nonstop. About his days “over there” with the Marines, never specifying which war. About “kids these days” wanting everything handed to them. About how he believed in tough love, in discipline, in “men being men and women not trying to be men.”

He asked only one question about me: “So you mostly do desk stuff now, right? Paperwork? You’re pretty high up there.”

“Operations and logistics,” I said. “I run planning cells, oversee—”

“Ah, yeah,” he cut in. “The brain stuff. Keeping the printer fed. Somebody’s got to do it.”

He chuckled. I let the words slide past like static.

We turned onto my mother’s street—narrow, tree-lined, houses hunched under tangles of Christmas lights. Hers used to be easy to spot: the slightly crooked snowman she painted herself, the handmade wreath of cinnamon sticks and red ribbon hanging on the door, the colored lights she refused to replace even when half the strands went dark.

The snowman was gone.

The lights were white and perfectly spaced.

And the wreath… the wreath was new.

Too round. Too perfect. Artificial pine bristling like plastic teeth, symmetrical gold berries spaced at mathematically flawless intervals. It looked like it had come out of a catalog, not a memory.

Something in my chest tightened.

Ron noticed my stare as we walked up the path.

“Nice, right?” he said. “I told her we had to class the place up a bit. That old thing she had? Cute, but… child stuff.”

“I made that old thing,” I said before I could stop myself. “When I was ten.”

He shrugged, unbothered. “Well, you grew up. House had to, too.”

The door opened before I could reply.

There she was. Smaller than I remembered, or maybe the house was bigger. Her hair had more silver, pulled back in a neat twist. There were new lines at the corners of her mouth, the kind you get from pressing your lips together instead of speaking.

“Lisa,” she breathed, and for a moment everything else dropped away.

I dropped my duffel and folded her into my arms, breathing in the clean powder smell of her detergent, the faint scent of the perfume she’d worn since my childhood. Underneath it all, I expected cinnamon, roasting turkey, something warm.

Instead, the air held the sharp tang of leather polish and some expensive candle that smelled like “mountain lodge” or whatever they’re marketing sterile air as these days.

“Hi, Mom,” I murmured into her shoulder.

When we separated, she kept one hand on my arm like she was afraid I’d vanish.

“Look at you,” she said. “You look tired.”

“Occupational hazard.”

Ron stepped past me into the foyer like he’d done it a thousand times. He took my duffel to the hallway without asking where my old room was.

Mom ushered me inside, talking fast—about how happy she was, how different things were, how “Ron’s been such a help.” Her voice had that bright, brittle quality of someone narrating a slideshow they didn’t choose.

I scanned the living room. The tree was tall, symmetrical, wrapped in white lights and matching gold ornaments. No lopsided styrofoam bauble with my second-grade photo. No string of popcorn we’d always half-finish before eating the rest on the couch. No felt stocking with my name crookedly stitched.

The furniture gleamed like it had been shined within an inch of its life. The old crocheted blanket my grandmother made was gone from the back of the couch, replaced by a beige throw that looked like it came with the catalog wreath.

“This looks… different,” I said carefully.

“Doesn’t it?” Mom said quickly. “Ron helped me update things. Said I deserved a grown-up house.”

She looked at him when she said it, eyes flicking to his face, gauging his reaction. He nodded, satisfied.

In that second, watching my mother wait for a man’s micro-expression like it was a weather report, I felt more off-balance than during any air assault I’d ever flown into.

Home, but not really.

I wrapped my hands around the mug of coffee Ron handed me later, fingers absorbing its heat even as everything else in the room felt cold. I listened to him talk. About discipline. About respect. About how he was “old-fashioned” and proud of it.

He called me “soldier” instead of by my name. Not once did he ask where I’d been this year or what I’d seen.

He didn’t need to.

He’d already decided who I was.

And the worst part was, my mother seemed to believe him.

Part 2: The Man at the Head of the Table

The next morning smelled like… nothing.

Growing up, Christmas morning meant waking to the assault of cinnamon rolls and turkey already in the oven, coffee so strong it could stand on its own. This time, I woke to silence and the faint scent of that fake “mountain lodge” candle.

I showered, pulled on jeans and a sweater, and headed downstairs.

Mom was in the kitchen, moving like a guest in her own home. The counters were clear except for ingredients laid out in precise rows. The knives were lined up by size. The salt and pepper shakers sat exactly parallel to the edge of the stove.

Ron leaned against the counter, arms crossed, overseeing everything like a foreman.

“Morning, soldier,” he said. “You sleep okay? Jet lag’ll knock you on your ass if you let it.”

“I’m fine,” I said. “Can I help with anything?”

Mom opened her mouth, but Ron cut in. “Nah, I’ve got a system. Your mom’s used to my way of doing things, right honey?”

She gave him a quick glance, lips twitching. “Yes, dear.”

The words sounded foreign in her mouth.

I stood there uselessly for a second, then reached for a cutting board.

“I can peel potatoes, at least,” I said. “I think I remember how.”

Ron chuckled. “We like them a little chunky around here. Her old way was like baby food. I taught her better.”

Mom’s hand hesitated over the bowl of potatoes, just a flicker, before she passed one to me.

“Chunky it is,” I said.

As we worked, he paced. He rechecked the oven even though the timer was running. He lifted the lid on the pot to sniff the gravy, then told Mom she’d probably overseason it. He moved the salt shaker a quarter inch to the left.

“You know,” he said, “back in the Corps, our mess hall operated like a machine. Everything had its place. That’s how it should be in a kitchen. None of this chaos.”

Mom laughed lightly. “I thought I was pretty organized before,” she said. “But Ron’s really helped streamline things.”

She said it like she was reading lines.

“You ran this house just fine,” I said, a little sharper than I meant to. “For a few decades.”

Ron waved his hand. “She managed. But every woman needs a man to take the lead, especially in a home. That’s just how life works.”

He said it in front of her like it was weather talk. Like declaring my mother incapable of steering her own life was just another opinion on football scores.

I felt the familiar warmth of anger starting low in my stomach. The sort that had nowhere to go in this tiny, spotless kitchen.

In Kandahar, when we walked into a room, I was the highest-ranking person there more often than not. My orders moved aircraft, rerouted convoys, redirected resources. Men twice my size snapped to attention when I walked in. Not because I shouted, but because the rank on my chest carried weight.

In my mother’s house, a stranger in a red flannel shirt carried more authority than I did.

It would’ve been funny if it hadn’t been so wrong.

By late afternoon, the table was set.

The “good” china, the one set I remembered from childhood, gleamed under the dining room light. But everything around it was changed. The handmade table runner was gone, replaced by a sleek gold one. The old mismatched chairs had been swapped out for six identical ones that matched nothing and everything at once.

Ron took the head of the table without question, like it had been carved there with his name. Mom started to sit across from him—where Dad used to sit—then hesitated and moved one seat down.

My chair was on the side. It felt symbolic.

Ron lifted the carving knife and fork like he was about to be photographed for an ad. He sliced into the turkey with exaggerated precision, glancing up each time to see who was watching.

“Now this,” he announced, “is a man’s job. Real men carve the turkey. Ladies relax. You’ve done enough.”

He winked at me. “Except for you, soldier. Bet you’d try to take the knife away if I let you.”

I forced a thin smile. “I’m perfectly happy with a fork, thanks.”

He laughed and looked to my mother for backup. She laughed, too, a second late.

We all bowed our heads for grace when he told us to.

“Lord,” he began, voice booming, “we thank you for this food, for this home, and for the strength you give to men to lead their families.”

He went on. About discipline. About sacrifice. About how “too many people today don’t know what it means to serve.” He never once glanced at me, the only person at the table still on active duty.

I stared at my clasped hands, jaw clenched, counting breaths.

On base, I sit at tables with generals who have learned that true authority doesn’t need volume. Here I was, sitting through a monologue disguised as prayer.

When we finally picked up our forks, the turkey was perfect. The potatoes were smooth. The gravy was rich.

The food tasted like remembering a song but not the words.

Ron poured himself another glass of wine. Mom took a half glass. I waved it away when the bottle tilted toward me.

“No thanks,” I said. “I’m fine with water.”

He arched a brow. “What, the Army doesn’t let you have a little fun? Or are you just that strict?”

“I’m on body clock time,” I replied. “Alcohol won’t help.”

He smirked. “That’s the thing about women who try to live like men. You get all tense and wound up. Can’t even relax on Christmas.”

He said it lightly, but the jab was clear. To him, my discipline was a flaw, not a strength.

Mom’s fork slowed. She didn’t look at me. Or at him. Just down at her plate.

“Anyway,” he continued, apparently bored with my refusal to react, “what is it you do again, exactly? In the Army. Paperwork, right? Logistics?”

He said “logistics” like it was a punchline.

“I oversee operational planning and—”

“So you’re the one typing up the reports,” he interrupted. “Making sure the printer’s got ink.”

He laughed at his own joke. “Hey, that’s important too. Keep the wheels turning, huh?”

I met his eyes. Held them for a beat.

“I’ve done my share of typing,” I said. “I’ve also been the one approving missions that sent aircraft into combat. The one whose signature moved entire units. The one your old sergeants would be snapping to attention for.”

The words lined up in my mouth. They wanted out. But I swallowed them.

Not because I was ashamed. Not because I was afraid.

Because I’ve spent twenty-three years learning that arguments with men like Ron rarely end with, “You’re right, I misjudged you.”

They end with shouting, slammed doors, or women left cleaning up the emotional mess.

So I let him think what he wanted. Let him keep his little fantasy of me as a glorified secretary with a neat uniform.

He kept talking. About “kids these days.” About “women who don’t understand their place.” About how lucky my mother was to have a man willing to take charge.

The room grew smaller with every word.

And somewhere between the mashed potatoes and the second helping of turkey, he decided he’d earned the right to break out the knives he liked more than the carving one.

Part 3: “Sit Down and Be Grateful”

He had one hand on his wine glass and the other stabbing the air like a conductor.

“I’m just saying,” Ron drawled, “a woman your age ought to be grateful there’s still a man willing to lead the table.”

The words floated for a second before they sank in, heavy as stones.

I set my fork down gently. “A woman my age?”

He nodded, oblivious. Or pretending to be.

“You know.” He swirled his wine, eyes on the deep red, not on me. “No husband. No kids. Always in charge at work, I bet. That’s lonely stuff. You get so used to barking orders, you forget how to let a man be a man.”

He finally looked at me, smiling like a doctor delivering a diagnosis he was proud of.

“That’s why your mom’s so blessed,” he continued. “She finally found someone who can take charge. You should respect that. Sit down, enjoy the meal, and be grateful you’ve got a man in the house who knows how to run things.”

The room didn’t spin. It didn’t explode. It just… crystallized.

My mother’s hand was on her napkin, twisting the corner. Her eyes were fixed on the tablecloth like the pattern might save her.

Somewhere inside me, something that had been rattling all evening clicked into place.

I’ve stood in rooms with maps spread out under harsh fluorescent lights, knowing that the lines I drew would change lives. I’ve listened to young soldiers argue, boast, crumble. I’ve heard fear in men’s voices and arrogance, and I know the difference.

What I heard in Ron’s voice wasn’t confidence. It was hunger. A need to be bigger than he was, fed by shrinking someone else.

He didn’t just dislike that I outranked him. He needed me to be smaller in front of my mother to feel big in front of himself.

I could have unleashed on him right there. I could have listed my rank, my years, my missions. I could have twisted the knife of his own mediocrity in his gut.

Instead, I felt a slow, steady calm roll over me.

“Jet lag’s catching up,” I said quietly, pushing my chair back. “I’m going to lie down for a minute.”

Ron snorted. “Fragile, huh? Guess all that paperwork wears you out.”

Mom opened her mouth. Closed it. Her fingers tightened on the napkin until her knuckles turned white.

I pushed my chair fully back, stood up, and left the table.

Not because I was retreating.

Because I was choosing my ground.

On the stairs, the house felt hollow. The photographs along the wall—old family vacations, school pictures, my father in his uniform—were still there. But some frames were missing, replaced by generic landscapes.

Half our story had been taken down and replaced by nothing.

In my old room, the furniture had been updated, but the bones were the same. The bed, the window, the crack in the corner of the ceiling where I’d once taped glow-in-the-dark stars.

My suitcase sat by the closet. I flipped it open, sifting past folded civilian clothes until my fingers brushed the smooth green of my dress uniform.

I hadn’t meant to wear it this trip. I brought it out of habit. There’s always a chance you’ll be needed somewhere formal, somewhere official. Military life is one long string of “just in case.”

I pulled it out, laid it on the bed.

The jacket was pressed, the creases crisp. My name—MONROE—gleamed on the brass plate. The silver oak leaves on my shoulders shone softly. Service ribbons, badges, all the little colored squares that meant something very specific to the people who knew how to read them.

I ran my fingertips over each row. Years of my life represented in threads and metal. Times I’d missed holidays, birthdays, funerals. Nights I’d sat in tents under humming fluorescent lights, writing letters to families of soldiers who didn’t come home.

Ron thought I ran the printer.

I unbuttoned my sweater, kicked off my jeans, and stepped into the uniform pants. The motion was automatic, muscle memory older than my last two relationships.

As I slid my arms into the jacket, something inside me straightened along with my spine.

This wasn’t about ego. It wasn’t about showing off.

It was about truth.

In uniform, I am myself in full. There is no shrinking, no downplaying. There is only fact: this is who I am, what I’ve done, what I’ve earned. To some people, that’s threatening. To others, it’s a relief.

Tonight, it was a line in the sand.

I fastened the last button, adjusted the collar. Checked the mirror.

A face stared back at me, harder around the eyes than the girl who’d first put this uniform on at twenty-three. Hair pulled back regulation tight. Jaw set, not in anger, in certainty.

The same calm I feel before a classified briefing settled over me. Focused, sharp.

Downstairs, muffled through the floor, I could hear Ron’s voice. Still talking. Still filling the air.

I smoothed the front of my jacket, squared my shoulders, and opened the door.

Each step down the stairs felt like part of a countdown. The carpet muffled my boots. The house, for once, didn’t creak.

When I reached the bottom, I paused at the edge of the living room.

Ron was mid-sentence, wine glass in hand, gesturing toward my empty chair. Mom’s shoulders hunched inward.

He looked up first. His words stopped. His eyes tracked from my boots to my rank to my face. His mouth fell slightly open.

Mom turned in her chair. Her hands flew to her lips. A sound escaped her—half-laugh, half-sob.

The Christmas tree lights blinked softly behind them, casting a faint reflection on the glass of the framed photo of my father in uniform on the opposite wall.

Three uniforms in one room. Only two of them had ever understood what that meant.

Part 4: The Confrontation

I walked into the dining room and took my place at the side of the table, where I’d been sitting in jeans and a sweater ten minutes earlier.

I did not sit down.

“Lisa,” Mom whispered. “You…”

Her voice trailed off. Her eyes glistened. Pride, fear, something else I couldn’t name yet.

Ron set his glass down. His hand shook just enough to make it clink against the wood.

“Wow,” he said, forcing a laugh. “Bringing out the big guns, huh? You didn’t need to dress up for me.”

I held his gaze. “I didn’t dress up for you.”

He tried on a smirk. It sat wrong on his face.

“Look,” he started, “if I upset you back there, I was just—”

“Ron,” I said, my voice low but carrying, “you are addressing a lieutenant colonel in the United States Army. You don’t speak over me. You don’t belittle my service. And you do not talk to my mother like she’s your subordinate.”

The words didn’t come out loud. They came out steady. Years of command briefings honed them into something sharper than shouting.

His spine snapped a little straighter. Old training, buried deep, surfaced. He might have left the Marines decades ago, but his body still knew what rank sounded like.

He pushed his chair back and rose, maybe out of some ingrained instinct to stand when addressed like that.

“Now, hold on,” he said. “I was just—”

“You were just what?” I asked. “Reminding me I should be grateful a man like you is willing to ‘lead the table’? That my mother should be grateful she finally found someone to ‘take charge’?”

Color rose in his neck. “You’re twisting my words.”

“I don’t need to,” I said. “They were crystal clear.”

I stepped closer, hands behind my back, parade rest without thinking.

“You think you understand power,” I said quietly. “You think it lives at the head of a table, in the volume of your voice, in the way people flinch when you correct them. You think leadership means never being wrong and never being questioned.”

He opened his mouth. I didn’t give him the chance.

“Real power doesn’t need to control every detail to feel safe,” I went on. “Real leadership isn’t rearranging salt shakers and criticizing mashed potatoes until the people you claim to love can’t breathe in their own home.”

Mom’s breath hitched. She covered her mouth with her hand again, but she didn’t tell me to stop.

“What you’ve been doing,” I said, “is not leadership. It’s control. It’s insecurity dressed up as authority. And you’ve been using my mother’s fear of being alone to justify it.”

Ron’s eyes flicked to Mom, searching for backup.

She didn’t look at him. Her gaze was fixed on me, overflowing now.

“That’s not fair,” he said hoarsely. “I’ve done a lot for this house. For her. I’ve been good to her.”

“Have you?” I asked. “When you correct her cooking in her own kitchen? When you talk about her like she’s lucky to have you instead of the other way around? When you erase her traditions because they’re ‘childish’? When you mock her daughter’s career in front of her to prove that you’re the only ‘real man’ at the table?”

He flinched like I’d slapped him.

“You don’t know what it’s like to come back to an empty house,” he snapped. “To eat alone. To—”

“I know exactly what it’s like to come back to an empty room,” I cut in. “To miss Christmases, birthdays, anniversaries. To lose people under my command and carry that loss alone. But I have never used my loneliness as an excuse to make someone else small.”

Silence wrapped itself around the room, thick and humming.

I turned to my mother.

She looked older and younger at the same time. Lines deepened by stress, eyes shining like I remembered when she’d watch me march across fields at basic training graduation.

“Mom,” I said softly, “you do not owe anyone your peace. Not me, not him, not anybody. You don’t owe anyone your silence so they can feel comfortable. You taught me that, remember?”

Her lips parted. For a moment, I saw the woman who’d stood in the schoolyard and told a bully’s mother, “My daughter will not apologize for speaking up.”

Somewhere along the way, that woman had started apologizing for existing in her own kitchen.

“I thought…” Her voice shook. She swallowed hard. “I thought it would be easier. Having someone here. Someone to… help. The house felt so empty after your father.”

“I know,” I said. “But easier doesn’t mean better if the price is you shrinking inside your own life.”

Ron took a step toward her, hand out. “Honey, don’t listen to this. She’s been gone. She doesn’t see—”

“Enough,” I said sharply.

He stopped.

“You told me to sit down and be grateful,” I said. “That’s a phrase you like, isn’t it? Puts people in their place. Makes you feel large.”

I met his eyes and let every ounce of rank, every hour in command, pour into my voice.

“So here’s what’s going to happen, Ron. You are going to sit down. You are going to listen. And you are going to be grateful that this conversation is happening in a dining room and not in front of a judge.”

His jaw clenched. “Are you threatening me?”

“I am reminding you,” I said evenly, “that intentionally damaging someone’s property and making a false report about them to law enforcement—both of which you’ve bragged about doing, by the way—are crimes. I am choosing not to pick up the phone right now. That is grace, not weakness. Do not confuse the two.”

His face went pale.

I hadn’t told Mom about the 911 call yet, the one he’d made earlier that week when a neighbor’s cousin parked “in his spot” in front of the house. How he’d exaggerated, how he’d puffed his chest and called it “putting people in their place.” I’d heard it on speaker when I called to say my flight was delayed.

It hadn’t sounded like a funny story then. It sounded worse now.

“You need to leave,” I said. “Tonight. Right now. This is my mother’s house. Not your barracks. Not your command center. You are not her CO, and you are not mine.”

He stared at me. At the uniform. At my mother.

“You’re making a mistake,” he muttered. “She needs me. You’re not here. You can’t—”

Mom’s voice cut through his.

“Ron.”

She said his name quietly. No tremor. No apology.

He turned, startled. In all his monologues, I wondered how often he’d actually heard her speak to him that way.

“This is my house,” she said. “My table. My life.”

Her hands were still shaking, but words flowed now like something dammed up for too long.

“I have been grateful,” she said. “Grateful for company. For help. For not eating alone. So grateful I let you move the furniture, change my recipes, take my wreath off the door. I thought that was compromise.”

She shook her head slowly.

“But I will not be grateful for being made small,” she went on. “I will not be grateful for being corrected like a child. I will not be grateful for you talking to my daughter like she’s less than you.”

Her chin lifted. For a moment, I saw the woman who’d marched into my principal’s office when I punched a boy for snapping my bra strap and said, “Next time, call me before you punish her.”

“If you cannot be in this house without needing to own it,” she finished, “you cannot be in this house at all.”

Silence. A deep, thick pause.

Then Ron grabbed for the one weapon he had left.

“You’re throwing away a good man,” he snapped. “For what? For her? She’ll be gone again in a week. Back to playing soldier. You’ll be alone. Don’t come crying to me then.”

My mother flinched as if the words had weight.

I stepped between them, not physically, but with my presence.

“If being alone is the price of not being controlled,” I said, “it’s a bargain.”

We held there for a long second.

Then Ron scoffed, low and ugly. He grabbed his coat off the back of the chair, knocked his wine glass over without bothering to set it upright, and stalked toward the front door.

At the threshold, he turned, looked back at me in my uniform, my mother at the table.

“You think that rank makes you better than me?” he spat.

“I think my actions do,” I said.

He shook his head, muttered something about “ungrateful women,” and yanked the door open. Cold air gusted in. Then the door slammed shut behind him.

The house rang with the absence of his voice.

For the first time all night, the quiet felt like quiet instead of tension.

Part 5: Afterwards, and the Years Beyond

We didn’t move for a long time.

The heater kicked on with a familiar wheeze. Somewhere in the distance, a neighbor’s stereo cycled into another Christmas song. The lights on the tree blinked, their reflection dancing in a half-spilled circle of wine on the table.

My mother stared at the door.

Then her shoulders slumped—not in defeat, but in release. Like someone finally putting down a bag they’d been carrying too long.

“I didn’t see it,” she said eventually. Her voice was soft and raw. “Not at first. It was… little things. He fixed the leaky sink. He carried in the groceries. He told me the TV was too loud, so I turned it down. He moved the furniture. He… moved the furniture,” she repeated, almost laughing. “And I let him. I told myself it didn’t matter. It was just stuff.”

I pulled out the chair next to her and sat, uniform creaking quietly.

“Then it was how I cooked,” she went on. “How I folded dish towels. What I watched. Who I called. I stopped telling you some things on the phone because I didn’t want to upset him. I told myself I was choosing peace.”

She looked at me, eyes shiny but steady.

“But it wasn’t peace,” she said. “It was… silence. And those are not the same thing.”

I covered her hand with mine. It felt smaller than I remembered.

“Loneliness can make a lot of things look like love,” I said. “Especially when the person knows exactly what to say and do at the beginning.”

She smiled sadly. “You sound like you’ve lived that.”

“I have,” I admitted. “Twice.”

We both chuckled, the sound fragile but real.

“I wasn’t planning to fight tonight,” I added. “I wanted to come home, eat your cooking, fall asleep on that couch watching bad Christmas movies.”

“You always fall asleep ten minutes in,” she said. “Your father used to take pictures of you snoring with your mouth open.”

We laughed a little harder. The room felt bigger.

“I didn’t want to cause trouble,” she said after a moment. “Didn’t want you to feel like you had to fix my life on your leave. You fix enough over there.”

“You’re not trouble,” I said. “You’re my mother. You’re the reason I know how to stand up for anyone at all.”

She looked at my uniform. “I always imagined you wearing that in big rooms. Important rooms. I never thought you’d have to wear it in my dining room just so someone would listen.”

“I didn’t put it on for him,” I said. “I put it on for me. To remember who I am. To remember that I’m allowed to take up space in this house, too.”

She nodded slowly.

We cleaned up together.

Ron’s spilled wine wiped away easily. The turkey went back into the oven to stay warm. The mashed potatoes reheated in the microwave tasted just as good.

We ate at the same table, two chairs this time, my uniform jacket hanging over the back of mine. We talked about small things and big ones. About my deployment. About her book club. About the neighbor’s new dog that barked at everything but butterflies.

When the dishes were done and the leftovers tucked into the fridge, we moved to the living room. I dug through the hall closet until I found the old crocheted blanket, stuffed behind a box of things Ron had labeled “donate?”

I wrapped it around her legs.

“Thought this was gone,” I said.

“So did I,” she replied.

We watched a movie we’d both seen a dozen times. Halfway through, she leaned her head on my shoulder like she used to when I was small enough to fit under her arm.

“You know,” she said quietly, “if you had not said anything tonight, I think I would have kept shrinking. Until one day I’d look in the mirror and not recognize myself.”

I swallowed.

“If you had not said anything,” I said, “I would have flown back, wondering if I’d left you in a place that wasn’t safe. And I would have carried that with me into every briefing, every bed, every holiday after this.”

We sat with that for a while.

Later, in my old room, I hung my uniform jacket on the back of the chair. The oak leaves glinted in the dim light.

I thought about all the tables I’d sat at where I didn’t speak. Where women swallowed their opinions to keep the peace. Where men like Ron filled the silence with their own comfort.

There’s a particular kind of strength in holding your tongue when you could lash out. There’s another in knowing when that silence has stopped being strategy and started being surrender.

I’d waited as long as I could. Tonight, I’d finally drawn a line. Not with anger, but with truth said plainly.

I slept better than I expected.

In the morning, Mom was in the kitchen, alone. Flour dusted the counter. Cinnamon filled the air. The wreath on the door was still the new one, but a box sat open on the table, the old cinnamon-stick wreath lying inside like an artifact ready to be restored.

“I saved it,” she said when she saw me looking. “He wanted it gone. Said it was ‘tacky.’ I told myself I didn’t care anymore. But I… I couldn’t throw it out.”

“Good,” I said. “It’s ours.”

We hung it together, the old wreath beside the new. Imperfect and perfect, side by side.

For the rest of my leave, the house felt lighter. She talked more on the phone, even when I was in the next room. She turned the TV up to the volume she liked. She burned the cookies one afternoon and laughed instead of apologizing.

Ron called twice. She let it go to voicemail. I didn’t ask what he said. She didn’t offer. Some doors, once closed, don’t need to be reopened for inspection.

A year later, I made it home for Christmas again.

The tree had mismatched ornaments. The popcorn garland was only halfway done because we’d eaten too much of it. The wreath on the door was the cinnamon one. The new one hung in the hall, demoted but still present.

Mom had joined a volunteer group, she told me, reading to kids at the library. She’d taken a painting class. She’d made new friends, the sort who texted to ask if she wanted to join them for lunch on days when the house felt too quiet.

“I’m not afraid of quiet anymore,” she said one evening, stirring a pot on the stove. “Because I know it’s my quiet. Not something someone handed me as a punishment.”

We ate at the same table. No head seat. We moved around, sometimes at opposite ends, sometimes side by side.

After dinner, we sat on the couch. She looked at me for a long moment.

“You know,” she said, “I didn’t realize how much I needed you to say something that night. I thought I was protecting you from worry. I thought I was protecting myself from loneliness. Really, I was protecting him from consequences.”

I thought of the countless people out there sitting at tables like that. Swallowing words. Telling themselves they were protecting the peace.

“If you ever feel yourself doing that again,” I said, “call me. Even if I’m twelve time zones away. I’ll remind you.”

She smiled. “You always do.”

That night, in my old room, I opened my laptop and wrote.

Not a report. Not an operational summary. A letter. To no one and everyone.

I wrote about that dinner. About the new wreath and the missing ornaments. About the man who mistook volume for strength. About the woman who almost disappeared under the weight of “be grateful.”

I wrote about the moment I walked down those stairs in uniform and about how the rank on my chest didn’t create my power—it just made it harder to ignore.

And at the end, I wrote this:

If you’ve ever sat at a table and felt yourself shrinking, you are not alone.

If you’ve ever listened to someone rewrite who you are to make themselves feel bigger, you are not crazy.

Silence can be strategic, but it is not a long-term home.

You don’t need a uniform to stand up. You don’t need medals to draw a line. You just need to believe that your peace is worth more than someone else’s comfort.

The world will tell you to sit down and be grateful.

Sometimes, the bravest thing you can do is stand up and say, “No.”

I hit save.

Outside, the house was quiet. The good kind.

The kind we’d fought for.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

“Die, Btch” Recruits Pushed Her Off the Rooftop | Then The SEAL Admiral Saluted Her

“Die, Btch” Recruits Pushed Her Off the Rooftop | Then The SEAL Admiral Saluted Her Part 1 The first…

He Laughed at My Outfit During the Ceremony — Then the Judge Introduced Me as “Major General”..

He Laughed at My Outfit During the Ceremony — Then the Judge Introduced Me as “Major General”.. Part 1…

My Dad Said I Was “Just Support Staff” — Then His Pilot Buddy Found Out I Led Delta Echo

My Dad Said I Was “Just Support Staff” — Then His Pilot Buddy Found Out I Led Delta Echo …

Karen Took My Son’s Dialysis Supplies at Gate – TSA Gave Medical Priority, 4-Hour Hold

Karen Took My Son’s Dialysis Supplies at Gate – TSA Gave Medical Priority, 4-Hour Hold Part 1 If I…

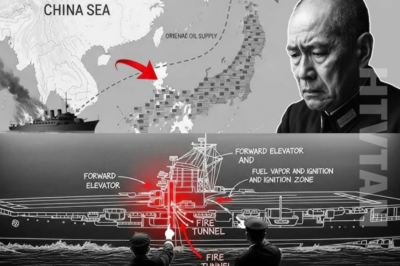

CH2. The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight

The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight The convoy moved like a wounded animal…

CH2. How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster Liverpool, England. January 1942. The wind off…

End of content

No more pages to load