Sick Wife Alone at Home, Husband Partying Abroad — “Get Better, I’m Busy” → Trip Ends in Surprise

Part One

My name is Mary. I am thirty-five, and for as long as I can remember my body has been a negotiator in a language I never learned. It started with colds that clung like reluctant guests and tests that required more bandages than classmates’ jokes. As a child I learned how slanted looks and whispered doubts could hurt more than any fever; I learned to tuck myself inside sweaters of silence and to make friends with the steady hum of quiet rooms. Illness became a private dimension of life—something I carried like a secret umbrella. People would see the faint shadow beneath my eyes or a pale hand and offer either pity or suspicion. Rarely did they offer simple curiosity: “How are you?” I learned to answer with “I’m fine” and keep the rest for family.

Work was its own education in that language. Early on I discovered this was a place where bodies were expected to stay in check, where sick days were measured and valued like currency. My training supervisor, a man with a voice like gravel and an affection for aphorisms, used to say, “Illness comes from the mind. Show some spirit.” He meant it as encouragement; I heard it as a verdict. So I built routines around staying available. I learned to push the weight of my small epidemics aside, to manage fevers and spreadsheets the way one might juggle ripe fruit—carefully, steadily, without dropping the most important piece.

It was in that rhythm—work, home, the occasional wave of fatigue—that Thomas found me. He was everything my life had not been: polished, outwardly effortless, the kind of man other people accepted as a natural fixture of a crowded room. He was university-elite in that casual, unexamined way, the kind of person whose resume reads like a promise. He worked at the same office and had the kind of smile that made men nod and women look twice. He asked me to dinner without drama and with a frankness that embarrassed me; I’d not been asked out like that for a long time. I misinterpreted the surprise in his invitation as a misdemeanor. “Sure,” I said, and then I spent the next day overthinking how many ways the evening could go wrong.

It did not go wrong. It went luminous—yearning thin as a knife, laughter that surprised us both, the small alchemy of two people noticing each other and liking the noticing. We dated. We bought a small apartment near the train station because it felt possible to live there. We married because one day we simply decided to be the people who made vows to each other. I thought my life had changed for the better. I thought I’d been rescued from the jagged edges of my own fears by a man who wanted the steady, quiet domesticity I’d come to treasure.

But the truths of people unfold like houses under renovation; you get to see wiring and support beams and old flaws once the plaster peels. By the time we had picked a modest table and argued over the color of curtains, Thomas began to show other aspects of himself—small at first, then steadily more insistent. He liked the good seams of civility: the way we presented ourselves at company dinners, the photograph of us at the park that fit so well on social media. He also liked the shape of convenience. The word “help” was elastic around him; when given, it grew thin.

There were nights I came home after long days and the apartment was cool and the dishes untouched, as if the day had not happened at all. The small, nagging pressures of my condition—fevers that made my legs heavy, headaches that made punctuation look like cliffs—grew into broader conversations he did not want to have. “Why do you take so many days off?” someone asked early on; I learned to answer with a guarded inevitability. “I’ll be fine,” I would say, and then work to prove it.

So when I took a day off and my fever climbed beyond the tender scale of “manageable” to a flaming, dizzying 104°, I believed what the body orders with rational insistence: go to the hospital. But before I could gather my things and arrange care, Thomas did something I could not have imagined even in my model of disappointment: he packed his carry-on, kissed my forehead as if stepping into a different apartment, and left without looking back.

“It was planned before,” his text read curtly when I called. “Take care of things here. I’ll be back.”

For thirty minutes after he left I lay beneath the duvet and practiced the shape of panic until it felt like a sculpture—edges manageable, the rest contained. Then the dizziness folded into a fiercer urgency. I called the ambulance on my own. My parents and my brother came after the beep of my message; in their worry there was no performance. The hospital smelled like antiseptic and coffee and the muted hum of life kept going as if nothing had changed. IV lines buzzed gently in my arm. The doctor said things like, “You must rest” and “You’re dehydrated” and “A few days under observation.” My family’s faces were damp with a righteous anger I recognized; they were not prepared to be disappointed by their daughter’s husband.

News travels in strange arcs, and rumors in office hallways are like moths to porch lights—they come because someone else set the light. When I told my brother the story of Thomas’s departure—how he’d left me with the fever and his curt texts—my brother became practical in ways I had known he could be. He asked for details like a detective. Who called? What did the message say? Did he have seats on his trip booked? Did he have a return date? People will surprise you in the way they choose to respond to your suffering.

My brother’s response surprised me. He is not theatrical by nature. He has been my quiet scaffolding for years—the one who comes with tea and a loaded dishwasher and the demeanor of someone who will fix things without announcing the fix. “Let him go,” he said once the facts were in. “Let him see what’s left.”

He had a plan that fit his temperament: it would be a small theater of mirror and consequence. He would, with the help of my parents, stage the subtle collapse of what Thomas took for granted. We would not make a spectacle; we would make a lesson. We agreed on a delicate ruse. I would let him think I’d died.

The thought of it was dangerous in its ethics and awful in its edge. But the truth is this: we had lived with a man who abandoned the woman for whom he had promised care. A fever was not enough to hold him; a woman’s life illness, hospital visits, was not a lever with which he would be moved. People who leave usually do not return out of loyalty; they return when they must salvage their own convenience. My brother’s plan was a mirror polished to show that fact.

We practiced the theatrics with a grim humor. I lay still at home while they arranged a message that would land like a stone in his pool of conveniences. My brother called Thomas pretending to be me at first, then became more somber. “She passed away,” he said in a voice made to be taken as truth. He said it with the sick gravity that the lie required.

For a few minutes Thomas’s reaction was precisely equal parts mechanical and rehearsed. He said the right things into the phone—“I’ll take care of things,” “I will come,” “I’ll inform my family”—and then, in a way that would later make my brother’s jaw drop, he said it as if it were an item on a calendar rather than a rupture. He spoke of “taking care of the necessary procedures” with the same manner as a man describing an errand. The casualness of it was a kind of violence, and it tightened my brother’s jaw.

After the phony “death” and when Thomas had a chance to process the news without the immediate heat of grief, the plan moved to the second act. I returned home to a house tidied to an extent that made the place feel like a museum. I scrubbed surfaces until they shone, folded laundry so precisely that the rooms suddenly seemed altered. It was a stupid, domestic ritual that felt like incantation: I polished things until they gleamed because I wanted to watch the reaction of someone who assumed my absence would be chaos. It is amazing what the absence of mess can do—it makes people look more carefully at emptiness.

That evening the phone rang. It was Thomas again, but there was something else in the tone now: uncertainty. “Hey,” he said with a forced casualness. “It’s odd… the apartment is so clean. Are you sure Mom hasn’t come by?” My brother, with an easy, conspiratorial laugh in his voice, confirmed the lie and let the caller stew in the ghost of propriety. The conversation ended with Thomas’s silence and a thin, unguarded fear that looked like it belonged to someone else.

Rumors spread at work because, of course, they would. Coworkers whispered. The rumor winds hooked into curious ears, and someone mentioned that the place had been cleaned by a ghost. Someone else called the police out of perplexity—there are social vertigo moments when the world is asked to refuse to believe. The officer was, as expected, baffled; nothing illegal had occurred. “Perhaps your grief is making you recall things differently,” he told Thomas with the practiced amnesty of someone who sees too many domestic oddities. The laughter the police officer shared with the story later would be a salve, but for Thomas at the moment it was a strange and prickling humiliation.

The cleaning escalated the small theater of moral truth my brother had built. Thomas began to call more often, the tone in his voice a shade thinner. When he returned home drunk one night—beer cans spiking the coffee table and the apartment smelling like someone else’s party—I rehearsed the most dramatic line I could imagine. I turned on the lights in the dark to stop him mid-snooze, and I walked into the room.

He leapt to his feet like a man tripped by an unexpected plate of glass. He saw me and for a second his face did the nearest thing to fear I had ever seen: not fear for me in any human way, but the fear of being caught in a spectacle. “You—” he stammered. “You’re—” His eyes were wet; his voice cracked into a sob. He fell to his knees as if the sight of me were a funeral rite.

“I’m not a ghost,” I said, voice steady as a thermometer. “I’m right here. The one who’s been left behind.”

And then the third act of the plan began: I called my mother and told her to come to the door, and she arrived with the woman who had shared gossip down the office hallway—a woman whose hands Thomas had been holding too long in the waiting room, a receptionist named Natali. I watched as the illusion disintegrated into the reality he had been hiding; the mistress’s embarrassment turned into a fraught apology. Thomas, suddenly unraveling, tried to make excuses while his mother called like a priest of familial wrath to condemn him. She had not known about the affair; the presence of a woman in the apartment summoned both outrage and the bitter, biblical sentiment of shame: this is not the child we raised.

I wanted to be angry. I was angry. I also wanted to be lucid. The mistress—Natali—bowed deeply and wrote on a notepad a promissory note promising to pay for any damages and to keep away. She was young and frightened and small. The sight of her apology somehow enlarged the absurdity: this was the equation he had chosen—late-night convenience in exchange for my hospital bed. Thomas’s face went pale under the shame, and his mother’s voice rose and broke like a surf of admonition.

There were things to do that night that felt like chores performed by someone new to the position of surviving. My brother made a call to a lawyer just to ensure we were moving with procedural sense rather than theatrical rage. We made a clear, pragmatic choice: I would file for divorce. There were reasons beyond moral failure—beyond the fear and the betrayal—and they were domestic and practical: a husband who leaves his wife while hers runs dangerously high with fever had shown the kind of character that will never build the scaffolding a marriage needs. I did not want a future built on vanishing attendance.

We took out the legal papers with measured hands. When I put my signature down, it was like sealing a letter to an imagined future that no longer included him. Financial settlement expected. Emotional settlements are less quantifiable, but with the help of my family and the lawyer we walked the practical path: damages, divorce, the kind of tidy justice that fits inside forms. I left him the apartment he had imagined he could convert into a cozy nest with another woman; instead I took an equitable share and moved into a small rental not far from the train line. The money from the settlement was not abundance, but it was enough to stitch a life so I could keep going to work, to pay for the bus, and to buy green tea in the mornings.

Part Two

The end of the marriage, with its odd relief and its bruises, was also a beginning in the most unclichéd sense: an opening in time that allowed things to happen one after another without the constant tremor of his presence. I threw myself into my work as one might throw oneself into water after being burned: cautiously, but with a clarity that comes from learned necessity. My boss noticed, as bosses do. “You’re reliable, Mary,” he said during a performance review. “We’d like to offer you a yearlong assignment overseas, if you’re interested.” My breath stopped in the strange, electric silence that follows a good door opening. The world had set out a counteroffer without a wink.

The yearlong posting was in a northern hub of my company—hands-on, single-site consultancy; a place where they needed someone who was fluent in English, meticulous with projects, and resilient enough to manage clients who required nuance. It felt like an answer I had not known to pray for, condensed into a promise the size of a plane ticket. I accepted with the practical joy of someone who marries the world not in romance but in the economy of possibility.

It was around this time that Thomas reemerged in the comedic, groveling way some men do when they have lost too much. He called from an unknown number several times; once he left a voicemail in which his voice unspooled into a mixture of regret and bewilderment. “I just wanted to hear your voice,” he said at one point, as if that were a tidy bridge to return by. It felt like a man offering a tissue in place of real help. I blocked the number. When someone shows up to clean the mess of their choices with apologies, I prefer to let time act as my counsel.

And then—perhaps the most exquisite thread of the years that followed—the company where Thomas had once been the up-and-coming star took notice of his failures. People talk in offices; they cannot help themselves. The Halcyon contract that had once sat like a prize at his firm’s table was quietly pulled away as clients grew protective. The small grace my father had extended by sharing his professional contacts became a story of consequence when a partner mentioned that integrity mattered more than a polished sales presentation. In other words, the social ecosystem moved around Thomas as if the rumor wind were a tide.

He lost prestige. He lost good hours. He kept his job for a while, but things were different. You could see it in how people now scheduled meetings without him as an afterthought. You could see it in the way HR offered a thin-faced “performance improvement plan.” He spiraled in the way men who stand on performance spirals often do—less sex appeal, less luck, more missed deadlines. He tried to repair the domestic ties with his mother and the woman he had married after me. Natali’s apology had been written in a notebook and in the end she did what a frightened young woman would likely do when faced with the margin of scandal: she left. Her career, too, was affected. People were, in small towns and corporate halls, unforgiving.

Several months after my overseas assignment was approved, Thomas called again with a voice I could have placed in a bar: frayed and frenzied. “Mary,” he pleaded, “it’s unbearable. I’m in a mess. She doesn’t cook. She doesn’t clean. My mother is ill. I can’t manage. Please—help me. Take me with you. Let’s start over.”

There was a place for pity, of course, but not a place for the removal of consequence. I had a plane to catch. I had a client waiting. The life I was building required me to be present in a way my marriage had revoked from me. So I refused. Work had become my new hearth; it demanded day-to-day labor, and I could not be a refuge for the man who had chosen a convenience over care. I said as much and then I blocked him once more.

His final attempt at reclamation was, however, more elaborate than a plea. He turned up at my parents’ house one rainy afternoon with eyes like a man who had failed to read a map. He expected me to be there, perhaps soft and ready to accept him back. Instead, he was met by my father’s measured courtesy and a demand for civility. My father had long ago decided that this man had not understood the chequered nature of consequence. He called the police when Thomas refused to leave my parents’ doorstep. The two-hour scene ended with Thomas being taken to the station and a note in his file for harassment.

News of the incident reached his office. The boss who had once praised his “sales charisma” read the police report and had no patience for someone who had become a public liability. He was dismissed. No fanfare, no final dinner—just a sudden end. Word on the street was that he had been “let go” for behavior that threatened their clients and for reputational risk. It was a small, fiscal justice: the man who abandoned his sick wife lost the assets the world had given him to test his character.

What struck me most through it was not the joy of his humiliation but the quiet confirmation that life is often less dramatic than people suppose. There is a string of cause and effect that has little patience for sentiment. He had chosen, through small acts, to be a man who left his partner when she needed him. The world returned those choices in kind.

I left the country six weeks after the divorce was formalized. The yearlong overseas assignment stretched into a life of projects and client-led retreats; I learned to present in auditoriums and to negotiate with people whose English accents made my training years feel like origins. The work itself became a balm—complex, demanding, and honest. When I visited foreign cafés in the evenings, they felt like small festivals in which I was learning a new language for taking care of myself. There were times in my new life when the old grief arrived like a storm in quick passages. But storms are weather; you put on a coat and step into the rain.

In my second year abroad, there was a story that filtered back through the corporate grapevine—Thomas had a new life, but it was not enviable. He worked the family business, a rougher, honest labor that was as grueling as a confession. Relatives reported he tried to leave again and again; they’d drive him back. He had debts incurred in his moment of self-pity. He had been humbled in a way that may, with enough time, have become a crucible for reformation. I did not watch him suffer, per se; I watched from a distance, like someone who notes that a weather pattern had finally changed course. I am not a punitive person. I do not take satisfaction in pain. There is only a long memory I choose to respect.

There were small rewards for my work: promotions, appointments, a sense that my body and mind had finally been allowed to be partners rather than enemies. I met new people and loved the work—enough, in fact, to consider staying abroad beyond the year. My illness, while still a factor, was managed with good doctors who took me seriously. No one laughed at the skeleton of my anxiety now; medical professionals listened with a rigor that my old supervisor’s aphorisms could never have taught.

In the end the trip—his trip—ended in a surprise, but the surprise was not glamorous. The surprise was the mundane justice of life: a man’s choices have costs; women’s choices do, too. The difference was that I had a family who would not drop me, and a world that rewarded steadiness over bravado. Thomas, for his part, had to live with the consequences of his absent kindness. He sought reentry and was refused by a door that had learned to be locked. He found himself asking for the company of someone he had not been willing to care for in sickness. That is, perhaps, the most common kind of punishment.

Once, coming home to visit my parents between contracts, I bumped into Natali at a small bookstore in town. She looked older than the woman I had first seen in his arms, a little stooped with the weight of learning. We spoke oddly, like two strangers who had once been part of the same meandering story. She apologized for everything she had been involved in. She had repaid, as best she could, small debts. She had tried to find work outside of the office where she had been a receptionist and had learned something of humility. “I was young,” she said. “I was stupid.”

We did not become friends. We were both survivors of a certain kind of human fallibility. I forgave her as much as I could—publicly, in that small exchange—but forgiveness has the architecture of a careful building: it doesn’t mean erasing the damage, it means not letting it be the only thing that anchors your life.

The true surprise—if there was one—was not in the humiliations that fell on the man who had left me but in the ways my life reproduced itself in softer, stronger textures. I found work that took my attention and time and grew into steady collaborations. I found friends whose capacity for patience matched my own need for it. I learned to manage the illness that had been the background noise of my life without letting it be the only thing that defined me. I learned to say “no” with the practical kindness of someone whose life is not a deficit to be discussed on a company dinner table.

Years later I would tell friends who asked about that episode the simple wry truth that made them laugh: “He thought my being sick was an inconvenience. So he booked himself a holiday. He returned home and found the holiday came with a babysitter he had not chosen: consequence.”

They laughed, and the laugh felt like a small bell. A man can travel abroad to celebrate a week of ease. He can forget to come home when his wife needs him. The surprise of the trip was its ending: humbleness rather than triumph, labor rather than leisure. It was a conclusion matched to the choices he had made.

In my last meeting with my now-ex-husband, after the divorce had been processed and the forms signed, he said one thing that stuck to me like a damp evening. He said, “I thought I was protecting us by keeping things simple.” It was a clumsy attempt at philosophy.

“You protected your comfort by ignoring my needs,” I said. The words weren’t cruel; they were plain. “You can protect yourself from the truth, but you cannot stop it from having effects.”

He understood that the truth had consequences in the form of lost prestige, awkward reputation, and an empty mantel in a home he once imagined he could reoccupy with a different woman. I did not gloat. I had my life to manage, my career, my health. I did what many people do when they decide that their life, once broken, can be made again: I chose the small acts that mattered over the large gestures that meant little.

The trip had ended in surprise. He came home to find he had nothing left but the consequences of his own choosing. I left and found a world that, for all its cruelties, offered me a steady place at a table I’d helped design. That, ultimately, felt like the best kind of ending: not a finale, but a beginning that was less afraid and more deliberate.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

“I don’t argue about monsters. I expose them.” — Jasmine Crockett’s on-air debacle left Stephen Miller devastated and Washington stunned.

He showed up to defend his wife. Then he walked away with his reputation in tatters. In what was billed…

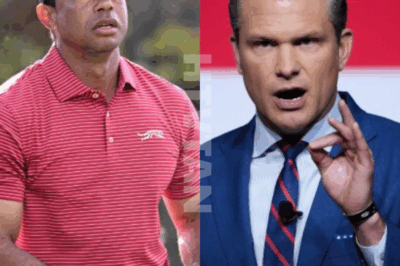

“BEATEN BEATEN – PAY NOW!” – Tiger Woods sues Pete Hegseth and Network for $50 MILLION after shocking direct attack. No one expected it.

What seemed like a normal interview turned into a war when Pete Hegseth directly attacked black golf legend Tiger Woods….

MIND-BLOWING SUPER BOWL REVELATION: Jimmy Kimmel BLASTS the Outrage Over Bad Bunny’s Halftime Performance, HILARIOUSLY Exposing the Absurdity of America’s Cultural Panic — And Drops a SHOCKING SECRET About What Really Went On Behind the Scenes, Revealing Hidden Decisions That Could Change Everything We Thought About the NFL, Pop Culture, and Latin Pride, While Millions Watch in Awe as He Turns Political Hysteria Into Comedy Gold, Sparking a Nationwide Debate That Nobody Saw Coming About Entertainment, Division, and the Truth Behind the Halftime Show!…Read more in comments👇👇

MIND-BLOWING SUPER BOWL REVELATION: Jimmy Kimmel BLASTS the Outrage Over Bad Bunny’s Halftime Performance, HILARIOUSLY Exposing the Absurdity of America’s…

BREAKING: Pete Hegseth BLASTS Harvard for Hiring Drag Professor “LaWhore Vagistan” — “This Isn’t Education, It’s a Circus!”

Could America’s most elite university really be turning classrooms into drag stages? Hegseth’s fiery rant over Harvard’s new courses, RuPaulitics…

“I WILL END MY SUPER BOWL SPONSORSHIP IF THEY LET BAD BUNNY PERFORM AT HALF TIME” — Elon Musk Issues Shocking Ultimatum, NFL’s Response Leaves Millions Stunned!

“I WILL END MY SUPER BOWL SPONSORSHIP IF THEY LET BAD BUNNY PERFORM AT HALF TIME” — Elon Musk Issues…

HOLLYWOOD PANIC: Jeanine Pirro just shocked the industry — praising The Charlie Kirk Show as “one of the most powerful ever” and confirming she’ll join Erika Kirk & Megyn Kelly on the next episode

HOLLYWOOD PANIC: Jeanine Pirro just shocked the industry — praising The Charlie Kirk Show as “one of the most powerful…

End of content

No more pages to load