“She’s dead” My father said under oath. The death certificate? It had my name on it. They moved $6m into an offshore account. The room stopped breathing when… I walked in—alive…

Part One

The courtroom held its breath the way a lung holds it before a scream. Fluorescent lights hummed. The judge’s gavel sat like an island of authority on an ocean of polished wood. Papers were shuffled; polite coughs died in throats. My father, pale and composed the way men who do monstrous things can be, had just finished speaking. “She’s dead,” he said under oath. It was a deliberate, ceremonial statement—three syllables meant to close a life.

They had signed the death for me with better manners than they ever used on birthdays. There on the table in the clerk’s hand was the death certificate: my name, my birth date, my mother’s name recorded like a ghostly breadcrumb, the illegible signature of a doctor who, I would later learn, had never touched my pulse. A single stamp, and the paper had become a professional eulogy.

The week after, $6 million moved. Quiet wires, offshore shells, names that sounded like wind. The bank statements that had always been harmless paper became instruments of erasure. I learned where money traveled when it wanted to be unfindable. They thought it was clean. They thought provision under ink and authority would make the world accept a person’s nonexistence.

They built the coffin themselves.

I did not scream, because noise is the first luxury murderers deny to their victims. Instead I learned to breathe slow and quiet, like someone practicing to become invisible.

I wasn’t always a specter. There were lives before that small, poisonous act: childhoods washed with sunlight and the small, foolish certainties that fathers protect daughters and that loyalty is a currency more valuable than cash. My father had been a legend in a particular town: the man who founded a company that built warehouses and a reputation that could not be shaken. People liked him the way they like the taste of something expensive—without necessarily understanding why.

I believed him. I took the weight of his pride as armor. I let him call me “his little proof” of the future he expected to outlive him. In the quiet of an office lined with family portraits, he taught me to value legacy. I learned a language—board meetings, ledgers, the polite arithmetic of taxes and trustees. It was not quite the life I would have written for myself, but when he smiled at me across a table, I believed my place in his plans.

That trust is what made the betrayal surgical.

It did not happen in an instant. Treachery rarely does. It came like rot at the seam of a roof—small at first, then consuming the beams. I noticed minute things. My name was spoken with a softness that sounded like a rehearsal. I watched my father glance at me in a way that belonged more to a hostage negotiator than to a parent: calculation tempered with habit. I found bank statements that were too tidy. Transfers were convoluted, routed through shell entities, creative account names like Orchid Holdings LTD and Sable Trust. There were plausible deniabilities and blank spaces. My cousin Daniel’s name showed up where it shouldn’t: flitting across wires as an authorized signer.

I remember an ordinary evening, a lull of rain, and the lawyer’s voice on a line I’d inadvertently heard. It was supposed to be logistically banal—paperwork, signatures, liquidation of an estate. The lawyer’s words were all protocol and then a fatal phrase: “Once the death certificate clears, the funds are untouchable.” My father’s reply—flat, clinical, final—was the sound of a man pronouncing someone dead before the world had had a chance to object. “She’ll never come back to claim them. She’s gone,” he said.

I went to bed that night with the sound of the lawyer’s voice like a chisel at my ribs. It would have been easier to die once and be gone. It would have been easier to roll over and accept the erasure. But some indignities demand a resistance that is not loud but is slow and relentless. I chose the slow path.

They had to believe I was dead. So I died to them on paper and in silence. I erased my public face. I canceled accounts, I stopped posting, I left my phone to the dark. To the world, I was a name on a certificate. To the people who had been making this quiet murder work, I was the absence they celebrated.

That invisibility was the first weapon they had not anticipated. When the world writes you out of its roster, you step into a place few minds understand: the ability to watch yourself become a rumor and then to watch those who authored the rumor begin to forget why they believed it true. Ghosts move where living people leave footprints. They are, by definition, unbothered by presence. People drop their guard in rooms they believe empty.

I spent months as a ghost. I studied offshore jurisprudence with the curiosity of a person learning the grammar of betrayal. I consumed books on trust structures, the mechanics of shell companies, how funds nest like matryoshka dolls in jurisdictions with names that tasted like secrecy. I watched and I mapped. Each wire transfer, each intermediary bank, every obscure company name became a clue; the so-called tidy list of transactions turned into a pathway leading directly back to a handful of people who had the motive and the audacity to declare me dead.

Running parallel to the financial study was the social study. I had to understand the players—my father’s temperament when cornered, Daniel’s greed, the lawyer’s penchant for risk, the bank manager’s need to avoid scandal. People leave patterns. They have habitual gestures they repeat even in the most elaborate lies. Daniel tapped a pen twice before he lied. The bank manager adjusted his cuff when embarrassed. My father stroked the carafe of water like a man putting down a lit cigarette. I cataloged it all.

I needed allies—intelligence eludes unassisted hands. The ghost does not conjure a battalion. Instead, she aligns with people who spend their lives tracing paper: a forensic accountant with a personal distaste for money laundering, a compliance officer who had been moved to tears in the past by the sight of a child orphaned by greed, an attorney in the city who had broken cases against money players and loved the aesthetic of truth. Their help was not cheap, nor was it free; it was bought with the currency I had left—time, personal accounts secretly maintained, and the truth I promised to deliver.

There was an art to collaboration. You cannot storm into a house of cards and demand everyone clap. You prick at the joints. You get a banker’s assistant to notice that a peculiar payment pattern mirrors another known scheme, and you set up a gentle conversation where someone becomes suspicious enough to place a call. You ask a lowly employee at a registry if a certain notarization has been completed; you discover a mismatched signature. You find that the “doctor” on the certificate is a retired clinician with a reputation for signing forms without seeing faces.

Daniel was a keystone. He was not brilliant; he was hungry. If greed has a smell, Daniel stank of it. I allowed him to find crumbs—a whispered hint that there might be a sliver of money for him if he could prove I had been reckless enough to squander something before my supposed death. He wanted proof of a different, darker pattern: he wanted to believe I had been planning a double life. He didn’t hesitate to show me vulnerability because vulnerability is currency to the people who trade in lies.

In return, he slipped. Human beings are skilled at clicking their tongues and forgetting they have left fingerprints. The passwords he thought were clever were significant footprints nonetheless. He saved a password in a folder called “FamilyAccounts” and wrote a note that meant little to anyone but everything to me. My forensic ally extracted digital breadcrumbs and—without glorifying methods or crossing into the dangerous territory of how-to—redirected me through legal channels. What Daniel thought he gave me out of treacherous comfort was the proof I needed.

I also used narrative. I started to weave a life back into my public presence but in the margins and in others’ rooms. I left a rumor that I had been traveling for a long-term project; I used a quiet, anonymous blog to post a few articles—commentary about estate law and the ethics of inheritance—so when the request for information from certain regulators arrived, it did not look odd that someone with a voice in the area would be checking documents. I sent discreet Freedom of Information inquiries that set bureaucrats to indexing. An avalanche begins with one snowflake.

By the time the courtroom date arrived, I had built a file thicker than many small books. It contained a map: transfers to an account in a small island nation, subsequent splits into corporate accounts, invoices that were boilerplate and obviously never rendered in the real world. It also contained Daniel’s passwords, emails suggesting the doctor’s signatory had been procured in a rushed hotel meeting, and a thin paper trail of corporate shells that suggested the $6 million had been positioned behind a network meant to make retrieval a nightmare.

I had to admit to myself that there was something feral in the preparation. Erasures are acts of intimate violence. Undoing them demands a similar intensity. I used my invisibility like a scalpel. Wherever papers were thin, I made them thicker. Wherever there was silence, I made it a place where people had to speak. The data turned into letters I could present in court.

Courtrooms have a rhythm that is almost theatrical: attorneys offer the music of deposition, the judge taps in baritone, witnesses scrape the proscenium of truth out of memory. My father had rehearsed his role. He believed in the choreography of power. He thought the rest of us would follow the script. He was wrong.

The day of the hearing, I wore dark, unremarkable clothes. Ghosts do not need to be dramatic. Ghosts need the authority of presence. I was not on the list of expected witnesses. That was strategic. The public record had me pronounced deceased. They had arranged their defenses in that certainty. When the judge asked, “Is the account transfer legal, and is the daughter deceased?” my father’s voice answered, “Yes,” with the authority of a man who had negotiated his exit from other people’s lives.

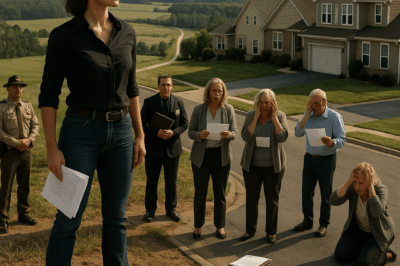

Then the door to the courtroom opened and I walked in alive.

The room stopped breathing in exactly the way it does when someone says something impossible and the brain scrambles to decide between denial and attention. People look at a living thing differently when they were supposed to be looking at an absence. A clerk dropped a pen. Papers halted in mid-shuffle. The heat of expectation cooled into the pinprick freeze of shock.

My father crumpled in his chair as if the floor had been swapped for quicksand. For the men who had been making death instrumental, presence is humiliation. My entry did not need fireworks. Quietly, calmly, I set a stack of papers on the table—carefully bound, annotated, redacted where necessary to protect whistleblowers, flagged in the places that would be impossible to explain away. I placed the forged signature copies, Daniel’s emails, timestamped banking logs that showed transfers to entities that existed on little more than chain-of-title illusions.

The judge’s voice, an instrument tuned to measured surprise, asked, “Who are you?”

My name came out steady. It was a reclamation: the syllables were mine again. The words were heavy. “I am she,” I said. “The one on that so-called certificate. The one who the defendant swore was dead.”

I remember that instant as sharp as a photograph: my father’s face crumpling, folding like old paper; Daniel’s darting eyes; the lawyer’s practiced mask splitting into a thin, human panic. I remember the officer who moved quietly to the doors and the pattern of the crowd’s breath as the room registered betrayal.

There is a peculiar kind of power in watching someone who has arranged a lie be forced to confront its consequences in public. For my father, it was a civil implosion. The legal matter that had been clean on paper was messy in person: signatures could be cross-referenced, bank logs could be subpoenaed, the doctor’s name could be interrogated. A forged certificate is an invitation to a much larger conversation when the person it purported to erase enters the stage and holds the evidence for all to see.

Offshore money is not invisible to the proper authorities if you nudge the right ones. The bank, which had been acting like a neutral instrument, sputtered when the compliance department received simultaneous inquiries: a police tax inquiry, one from the international financial crimes unit, and a subpoena from a court. These are not coincidences. They are the bureaucratic equivalent of closing the net. The $6 million that had seemed to flow into silence began to sputter in its channels. The transfers slowed. A freeze was requested. Letters crossed oceans in certified envelopes, and the language of “good faith” was replaced by the language of “probable cause.”

You might expect that the moment of triumph resolves everything. It does not. It only changes the nature of the fight. A legal freeze means investigations, asset tracing, interrogations, and a set of lawyers who, once they realize the scale of the game, will use every quiet, legal trick to delay, to obfuscate, to wear down resolve. That is when grit—humane, boring, stubborn grit—matters. I had grit. I had allies. I had the truth framed and packaged.

In the days that followed, indictments were quietly prepared. The press called it a scandal: Business tycoon and nephew arrested in multi-million dollar scheme. Headlines do their trade in condensation, but the truth moved in careful, patient detail: the death certificate was exposed as a piece of sophisticated forgery, the offshore accounts were revealed to be a network of conduits intended to hide the trail, and individuals who had signed documents for a fee were called into court to explain a signature they had not witnessed.

My father’s empire—built on concrete and contracts—was not so much battered as undermined. People who once pretended his gravity became concerned about their own reputations. Directors resigned politely; trustees distanced themselves as one would smoke away from a spark. Daniel, who had been the co-conspirator, was arrested when a port operator noticed cargo manifest irregularities linked to an entity he controlled. He tried to run. He could not run fast enough from logs that held his footprints.

It was one thing to catch them on financial perfidy; it was another to confront them on the moral stage. In a hearing that felt at times like a public exorcism, I laid out the narrative—how he had written my death into officialdom, how he had moved $6 million into accounts designed to spin away like eddies. I read my own words from the email I’d intercepted—the one intended to be a snuff that turned my life into an estate file. I let the judge and the gathered attendees hear the casualness of their cruelty.

There was no cinematic execution. No sword of righteous vengeance. There was the quiet efficacy of paperwork and the measured, legal machine. My father’s world began to reorder itself under the weight of facts rather than the vice of habit.

Part Two

After the indictments, the public gaze shifted from surprise to spectacle. Media vans littered the courthouse steps. Opinion pieces debated the ethics of wealth, the corrosive power of entitlement, and the rarity of a woman who had been declared dead appearing at her own hearing. People sent messages: some were condolence, others congratulatory, and many were the blunt, blunt joy of an audience that loves a story of comeuppance.

For me, however, the aftermath was not theater. It was inventory: a careful, domestic, painstaking sorting of what it means to be legally recognized as yourself again. Systems take echoes; bureaucracy requires signatures. I had been “dead” on paper for months, which meant contracts needed revisiting, tax forms needed correction, and an assortment of people who were curious about their own liabilities needed to be addressed. The bank accounts frozen under suspicion remained inaccessible, and the $6 million was tied up in legal knots pending the fruit of the investigations.

I learned the law’s pace—glacial, purposeful, laden with precedent. Every motion filed in my name felt like a pebble thrown into a vast lake; the ripples would be visible, but slowly. I learned to be patient in a way that is not an act of submission but an exercise of endurance.

My father was arraigned, trusting—as some do—that he would wriggle out. Pride is an odd, brittle thing. It does not accept small defeats; it demands spectacles. Watching him in court after seeing his clothes hang on him like a suit of rusted armor, I felt a complex bundle of things: grief for who he might have been before his decisions made cruelty habitual, anger at the coldness with which he had used every tool at his disposal, and a curious, almost theological, peace in knowing that justice—slow and indifferent—had a process and that process was working.

Daniel’s arrest was less complicated. Greed, when it meets proper scrutiny, is clumsy. He had not understood the sophistication of the legal net my allies set in motion. He had thought he was clever because he had practiced dishonesty within a small, private circle. The internet, the authorities, the compliance officers—they move in a different order of scale. His imprudence became a case study in my evidence.

My mother was, if anything, the saddest character in the drama. She had always been an instrument of social performance: invitations, appearances, the maintenance of an image. She had watched her husband make a decision that declared me dead, and she had either understood or been willfully ignorant. Later, when the truth stained her parlor and her name carried the smell of scandal, she found herself playing the role of the accused widow, then the humiliated partner. There is a cruelty to the public’s desire to see the woman who allowed a murder-of-reputation punished. Empathy was thin in those days.

I will not pretend the victory felt whole. Reclaiming identity is quieter than most scripts suggest. There are legal acts—an annulment of the death certificate, a cascade of paperwork in municipal and national registries, notifications to insurers, creditors, to the registry of births and deaths that your name is to be crossed and then uncrossed. But there were human ripples: friends who distanced themselves for fear of association; colleagues who looked at me with the awkward curiosity of people who do not know how to treat a survivor; and, always, my father, whose eyes I could not meet without seeing someone who had tried to buy oblivion.

The courts, however, acted where the world of paper and law can act decisively. Forensic audits separated the tainted funds from legitimate business income. The $6 million—partly recovered, partly contested—was frozen. That money was not going to be quietly reallocated. In a slow-motion drama performed by accountants and jurists, portions of the frozen funds were earmarked for restitution, fines, and legal costs. A portion was set aside pending criminal forfeiture. Lawyers murmured about cross-border complications; governments exchanged notes. It was not a perfect retrieval. That is rarely the case when wealth crosses borders built to harbor secrecy. But the important thing was that the act of theft—the declaration of my death to capture a financial prize—had been recognized in public as a crime.

There were consequences beyond the ledger. A board of directors with which my father had surrounded himself—men who enjoyed his charm and tolerated his misdeeds because they made money—rapidly recast themselves in the post-scandal image. Some resigned. Others pleaded ignorance. The company my father had built entered a transition period that required new governance. That collapse did not thrill me. Corporations are not neat villains; they are collections of people and jobs and communities. I felt discomfort at the ripple effects of the fall. But accountability demanded reconfiguration.

I also had to decide what to do with the part of the money that the courts allowed to remain for restitution and philanthropy. The temptation to use it as a weapon was real. I might have exacted a private revenge that would have felt satisfying. But I had preferred another course. In quiet conversations with the forensic accountant—a woman named Sophie who had the humor of someone who had seen too many men underestimate paperwork—we designed a trust. It would fund scholarships for girls from towns like the one I had grown up in, legal aid for whistleblowers, and a program to support the families of people harmed by white-collar crimes.

There is a grace in converting a wound into public good. The trust was not retribution. It was a reclamation of purpose. The money, tainted by betrayal, was redirected to protect others from similar erasures.

Personal repair is different from legal repair. My relationships with family members were rewoven in a cautious pattern. My father was convicted on several counts of fraud and conspiracy; his sentence was long enough to give him the time to think in a room that had nothing to do with work. Did I feel vindictive pleasure when he lost authority? I did—but it was tempered by the sorrow one feels for a person who has committed to a cruelty that rearranges his entire life. I had a complicated empathy for him: an understanding that choices are always entangled with the person one has been taught to be.

The town outside the courthouse continued to exist. People went to work. The small coffee shop on the corner where my father used to have breakfast closed for a week and then reopened under new management. Life resumed its modest beat. I, too, had to return to the ordinary. I renewed leases, signed paperwork that made my name present and solid in registries, and visited a friend who had been a mirror to me when I was a ghost and who is now a witness when I am a person.

There were quieter victories too. People I had long thought indifferent—neighbors, old teachers, a cousin who had been quietly loyal—reached out in hesitant ways. Forgiveness is not freely given; it is earned. Many of the small courtesies and apologies became behaviors over months and years: a delivered casserole, an offer to watch my son for an afternoon, a phone call that was not an inquiry but a conversation. Those little things, mundane and unrehearsed, mattered more than the headlines.

On a small afternoon in late spring, I walked into the company compound without the weight of being erased on me. The building smelled the same—polished wood and the faint metallic tang of ambition. Men in suits shuffled with the careful choreography of people who have learned the music of power. But this time, I walked in with a different quality of presence. I had been declared dead and had returned. There is an odd humility in knowing that nothing binds you except the truth you hold and the compassion you choose.

My son, who had been young when the scandal broke, is now older—old enough to ask direct questions and to demand honesty. He sat with me one night and, in a voice that sounded like a tomorrow, said, “Will they ever stop thinking I’m less because of what happened?”

I thought of my father’s eyes in court, the way the man had used him as part of a display. “People will have their opinions,” I said. “What matters is what you choose to carry. You can be afraid, sometimes. But you can also choose to be generous. These are both choices.”

He nodded, and in that simple moment I felt the end of a long tunnel. Not the end of consequence, never that; rather the end of a particular kind of fear that sits like static in the brain. We moved on in small steps. We planted a tiny garden in the yard where the money had been discussed in secret. We sat on the porch and watched life happen—not impressed, not triumphant—simply present.

There is one scene that remains crisp in my memory: the day I walked back into the very room where the death certificate had been discussed as if it were parchment. My father was not there then—he was behind bars, silent in a place that would allow him to think or to harden, depending on what you believe about people. Daniel’s trial was a television miniseries of sorts for local press. The courtroom, the judge’s voice, the thud of gavel—these were now ordinary sounds. The extraordinary part was the air inside me: cool, composed, satisfied without the need for vengeance.

When all was said, we had achieved legal restitution. We had restored my name on the registry. We had returned some of the money to accounts that would be used for public good. My father had been removed from his throne of convenience. Daniel had been convicted. The lawyer who had been complicit in the forgery served time for his role in the scheme, and a number of complicit professionals found their licenses revoked.

But what the headlines never captured—no 24-hour news cycle ever could—were the small residues of life: the quiet cups of coffee with friends who had stayed, the laughter at our kitchen table where the older cases of argument had once resembled earthquakes, the daily rhythms that stitch a life after drama. The trust we formed in the shadow of betrayal became something like a new ethic. We rebuilt slowly. The public’s attention drifted. The scandal became another file in the city archives.

And yet, sometimes, late at night, when the house is quiet and the streetlights make ribbons along the pavement, I replay that moment in the courtroom. The silence that had sat like a boulder in my chest cracked, and sunlight poured through. The world had assumed I could be purchased into nonexistence. They had been wrong. The suddenly loud, terrible clarity of my own survival—of going from nameless absence back into speech—was less a spectacle than a reclamation. I had not come back for vengeance alone. I had come back to tell the truth and to possess again the ordinary rights everyone mistakes for trivial: the right to a name, the right to breathe in one’s own life, the right to be recognized as a person.

People sometimes ask if I forgave him. Forgiveness is a private architecture. I do not think of it as an absolution I could give fast or freely. I think of it as a choice I refused to make for a long while, then made in small increments that were more practical than poetic: I forgave him enough to let him be small and human in the place that denies his power; I did not forgive the choice that declared my death as a strategy. That distinction matters. You can separate the person from the crime and refuse to let the crime become the story that defines you.

If there is a moral to this story, it is not the revenge arc so popular in novels or movie screens. It is that names matter, and that the machinery of law—slow, officious, stolid—can do what intention alone cannot always manage: restore name and status and, in so doing, dignity. A death certificate can erase you in paper; it cannot erase you if you choose to return.

In the end, I stood on the courthouse steps with my stack of cleared documents and a passport with my name in it. There was no triumphant music, no film-worthy close; there was only the wind and the ordinary city sounds. I felt a particular, reluctant satisfaction. The people who thought they could bury me had built their own narrative tomb, and the corridor I walked out of was wider than the one they had tried to narrow around me.

They moved $6 million to buy quiet and they discovered too late that some kinds of silence are weapons turned back on the hands that forge them. The room stopped breathing the moment I walked in—alive—and the world remembered how to look at me again. I slept that night, finally, like someone who knows the difference between a life lived and a certificate assigned.

The legal process continued long after that first dramatic day. Appeals, settlements, and whispers of complicity stretched into time like a shadow. But life, in its smaller ways—the garden we planted where the lawn used to be, a new trust that kept watch over something good, the honest watching of my son as he grows—these are the things I measure now. I do not need to be grander than my ordinary acts. I simply need to be here.

The last image I carry forward is not the judge’s gavel or the headline. It is my father’s hand reaching for me as the officers moved in, the tremor in it like a man who has lost everything and is only just discovering the weight of his choices. I did not take his hand. I considered it, as a camera sometimes considers the logistics of mercy. Then I turned instead to the space where my son had been waiting, to the family that had chosen me for who I am, and to the people whose small acts of courage—Sophie the accountant, the compliance officer who filed a late-night report—had made justice possible.

We arranged for the trust to support legal clinics and scholarships and, perhaps most painfully meaningful to me, funding for a small center that helps people whose identities have been erased by fraud. The money, which had almost been the instrument of my erasure, became a tool for protection. The professionals who had worked for me refused to take a public bow. That is how they wanted it. Quiet regained its dignity.

People sometimes ask, when told the story, whether a death on paper is as terrifying as a gun. It is and it is not. Erasure by procedure is a cruelty that moves inside forms because forms have the authority to change lives. That authority required the patience and the stubbornness of many small people’s courage to dismantle. I was one of them. I was also the product of others’ small, brilliant decisions to act.

So if the room ever stops breathing when you walk in, know what that silence might mean: it might be shock. It might be the sudden realization that a life cannot be purchased into oblivion. Walk deliberately into that silence. Gather your evidence: the receipts of memory, the names of allies, the documents that will become threads. And then, when the timing is right, open the door and let yourself be seen. The law will be slow and imperfect; the world will be messy. But names—our fragile, stubborn, luminous names—matter. They are why I returned, and why, in the end, I kept my place in the world.

Part Three

The first time I visited my father in prison, the correctional officer called my name like it was a question someone else should answer.

He read it off his clipboard, frowned, and looked up at me as if a glitch had walked through the metal detector. There was a beat where the universe seemed to remember that, on paper, I was supposed to be gone.

“You’re… her?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “I’m the one who didn’t stay dead.”

Humor is a strange armor. It didn’t fit quite right in that fluorescent-lit corridor with its chemical-cleaned floors and buzzing cameras, but it kept my knees from buckling. The officer shrugged in that institutional way people do when something is above their pay grade. He passed my ID back to me and buzzed open a door.

The sound of that lock disengaging felt like a verdict.

Inside, the visiting room looked like a cafeteria that had given up on joy. Tables bolted to the ground. Chairs that assumed no one would be comfortable for long. The air smelled faintly of instant coffee and disinfectant, like someone had tried to wipe away humanity and only gotten halfway there.

I saw him before he saw me.

He was smaller. That was my first thought, and it landed with a cruelty I hadn’t rehearsed. My father had always filled space—boardrooms, living rooms, the doorway of my childhood home. He’d owned air the way some men own land. Now he sat at a metal table in an orange jumpsuit that made his skin look sallow, his shoulders caved inward like old scaffolding.

For a second, my body tried to offer me an old script: go to him, let him hug you, let the past rearrange itself into anything but this. But then the echo of his voice on the witness stand slid in front of that instinct:

“She’s dead.”

I crossed the room instead and took the chair opposite him.

He looked up, and the expression that crossed his face was not one I had ever seen there. Not the proud father, not the calculating businessman, not even the irritated patriarch who’d grown impatient with my questions over the years. This was something bare and startled—like a man who’d opened the wrong door and found his conscience sitting inside, waiting.

“You came,” he said.

“You asked,” I replied.

He had written from prison exactly twice. The first letter was stiff, a product of a mind more familiar with quarterly reports than apologies. He wrote about “optics” and “unfortunate decisions,” as if my near-erasure had been a bad quarter he meant to correct next fiscal year. I threw that one away.

The second letter had been different. The neat handwriting had turned erratic, the sentences less curated. There were fewer numbers, more pauses. At the bottom, after a paragraph about how the food was terrible and the mattress was thin, he had written: I don’t know how to live in a world where you’re alive and I did what I did. If you want answers, come.

I wanted answers. I also wanted him to have to say them out loud.

“I wasn’t sure you’d… actually walk through that door,” he said now, watching me like a man watches a storm front.

“I wasn’t sure either,” I answered.

We sat in silence while the rest of the room filled. Other inmates trickled in, wearing their own fatigue and regret in varying degrees. Families settled at neighboring tables, their conversations a low, constant hum—children asking when they could go home, women discussing lawyers, men talking about time the way farmers talk about weather.

“I look older, don’t I?” he said finally.

“You look like someone who’s not in control anymore,” I said. “I guess that comes with wrinkles.”

His mouth twitched. It might have been the ghost of a smile, or simply the muscle memory of a man used to turning everything into banter. But whatever comeback he’d once had at the ready, prison had dulled it.

“I need you to tell me the truth,” I said. The words came out calm, but they tasted like iron. “Not the lawyered version. Not the one you practiced with whatever conscience you still listen to. The truth. Why did you do it?”

He folded his hands on the table. In another life, in another outfit, it would have looked like he was about to make a pitch.

“I thought I had more time,” he said.

“More time for what?” I asked.

“To fix what was broken,” he said. “To move some things around, to make sure the business survived… to make sure you—” He paused. “To make sure you were taken care of, even if we… fell out.”

“You don’t fake someone’s death to take care of them,” I said.

His eyes flinched. “You don’t understand what it’s like when everything you’ve built starts to tremble,” he said. “The company was exposed. We’d expanded too quickly, leveraged too much. Some deals went bad. Others were… under investigation. If they came after me, everything—everything—was going to be picked apart.”

“This isn’t about the company,” I said. “This is about the part where you stood up in a courtroom and erased me.”

He exhaled, a sound from somewhere between defeat and irritation. “The estate plan was supposed to protect the assets,” he said. “Move them somewhere safe. Keep them out of reach of lawsuits, government hands, vultures. We’d put you in as a central beneficiary years ago. Too central. They would have come after your share, too. I thought if…”

He stopped.

“If I were dead,” I finished for him, “then there would be no one to question where the money went.”

He met my eyes, and I saw it—the cold math he’d done, the column where I had become a line item.

“It was supposed to be a paper maneuver,” he said more quietly. “Legal fiction. A way to move numbers. Not…” His hand opened in the air, as if he could scatter the consequences like dust. “Not this.”

“You sat on a stand and swore to it,” I reminded him. “Under oath. There’s nothing fictional about that.”

“Sometimes you start playing a role and the stage swallows you,” he said. “One lie to keep regulators calm, another to keep a partner from bolting, another to make sure a cousin stays quiet. Eventually the script’s writing you.”

I thought of how he had once told me, with a kind of smug affection, that business was theater for men who didn’t like costumes. I had been eleven, and I’d thought it was profound. Now I understood it as confession.

“When you said ‘She’s dead,’” I asked, my voice thin, “what did you see in your head?”

He blinked, and his gaze went somewhere over my shoulder, to a memory no one else could watch.

“I saw you at thirteen,” he said slowly. “Standing on that rickety dock at the lake, daring me to jump into the water with my suit on.” He shook his head once. “I saw you at graduation, refusing to smile because you’d decided smiling for cameras was ‘performing capitalism.’” The corner of his mouth curled. “I saw you in my office, arguing with me about why we should stop using one of our contractors because their labor practices were ‘medieval.’”

He swallowed. “I saw all the times you would not let me make you into what I needed you to be.”

“And that made it easier?” I asked.

“That made it… possible,” he admitted. “You were already halfway out of my orbit. You’d quit the company, you were starting your own practice, you were… independent. It was like you’d already died to the life I’d planned for you. So I—” He faltered. “I convinced myself it was… efficient. To make it official. On paper.”

Efficient. The word landed like a slap.

“You turned me into an efficiency,” I said. “A clean line in a ledger.”

His shoulders sagged. “You were never that,” he said. “Not really. But I treated you like it, and that’s the part I can’t… undo.”

We sat in that for a while: the wreckage of choices stacked between us like files.

“Did you ever think I might actually be gone?” I asked, quieter now. “Really gone? That there might be a crash or a disease or a freak accident and the universe would make your lie true?”

His eyes went glassy. “Every night,” he said. “Every night after I signed those papers. I’d wake up and hear a siren and think, That’s her. That’s God making it neat. It didn’t feel like a lie anymore, just… an early obituary.”

“And you were okay with that,” I said.

“No,” he answered. “But I’d built so many rooms inside the lie that I didn’t know how to leave it.”

The thing about finally hearing the truth is that it’s rarely as satisfying as you want it to be. It doesn’t arrive like a glowing sword. It comes hunched and stammering, wrapped in excuses and self-preservation and the kind of half-remorse that still wants to be understood.

“I needed you to say it out loud,” I said. “So that when my son asks me, ‘Why did he do it?’, I can say: ‘Because he loved control more than he loved being honest about his fear. Because he didn’t know how to live without being the one who holds the money and pulls the strings.’”

“I loved you,” he said, the words hitting the table with a dull thud. “I still do.”

“I believe you,” I said, and I did. “That’s what makes it worse.”

He flinched again, but this time there was no comeback, no justification. Just the raw, unpleasant fact of himself.

We talked for an hour. About logistics—appeals he was considering, books he was reading, the mundane humiliations of prison life. About my mother, who had finally stopped hosting charity luncheons and started attending therapy twice a week. About my son, who played basketball and liked math and had inherited a stubborn streak that ran like a musty family heirloom through our bloodline.

He told me about the other men inside—white-collar criminals who couldn’t believe they’d actually been caught, who spoke of their sentences as if they were bad business deals they meant to renegotiate. He told me about the one man who walked the yard every day reciting the names of everyone he’d hurt, like a rosary.

“I tried that,” my father said. “With you at the end of the list. It took a long time to get there.”

“I should be at the beginning,” I said.

“Yes,” he agreed. “You should.”

The loudspeaker crackled, announcing the end of visiting hours. Chairs scraped. Guards moved to their stations, the practiced choreography of separation.

He reached across the table, his hand hovering in that space where a father would normally pull his daughter in, ruffle her hair, squeeze her fingers. This was the same hand that had signed away my life for six million dollars and a sense of safety.

I looked at it. The skin was thinner now, the veins roped and blue. My memories were full of that hand: steadying my bike when I first learned to ride, flipping through documents on a plane, patting my shoulder in a gallery when I’d gotten into a college he approved of.

Somewhere, in an older version of this life, I might have taken it.

In this one, I let it hover.

“I will send you whatever paperwork the lawyers need me to sign,” I said, standing up. “For the restitution. For the trust. For whatever good can still be scraped out of this.”

He nodded, his hand falling back to the table, useless. “Will you come again?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I think I have to live a little more before I decide.”

The guard opened the door. The lock clicked again, the metallic punctuation mark on our conversation.

As I stepped back into the bright corridor, an officer checked my stamp, glanced at my ID, and waved me through. His eyes didn’t linger like the first guard’s had. To the prison’s system, I was just another visitor now. Alive. On the list.

Outside, the air felt too big, like I’d stepped out of a vacuum into open weather. I stood on the sidewalk and watched the razor wire glitter in the sun. Somewhere behind those walls was the man who had written my death certificate into the margins of his empire. Somewhere in front of me was my car, the road, the trust, my son, and a future that no longer had to orbit his choices.

I turned toward the parking lot.

On the drive back, Sophie called.

“How did it go?” she asked.

“He’s smaller,” I said.

“Time has a way of doing that to people who thought they were the largest thing in the room,” she replied. “On a practical note, the judge signed off on the foundation’s tax status. We’re official.”

The foundation. The trust we had set up in the shell of the stolen money. It had a name now: The Registry Center. It sounded bureaucratic and nondescript. That was by design. Buried inside the blandness was a revolt.

“We’re ready to start taking cases?” I asked.

“We already have one,” Sophie said. “A woman in Ohio. Her ex-husband faked her death to cash in a life insurance policy. The insurer’s pretending it’s a clerical error. She’s been fighting alone. She heard about you from a podcast.”

Of course she had. America turns everything into content.

“Send me the file,” I said.

As I hung up, I realized that this was the true aftermath: not just living with what had happened, but choosing what to do with the skills I’d gathered as a ghost. I had become fluent in betrayal’s paperwork. Maybe, just maybe, I could use that fluency so the next woman declared dead on paper wouldn’t have to learn the language alone.

The road unwound ahead of me, strip malls and overpasses and small patches of trees. Ordinary America. It looked nothing like the inside of a courtroom, or a prison, or an offshore bank’s server room. And yet, every house I passed contained people with names—fragile, stubborn, luminous names—that could, under the wrong hands, be turned into lines in someone else’s ledger.

I rolled down the window and let the wind rush in. The noise felt like proof: I existed. The sun was too bright, the air too warm, the future too unwritten to pretend I was a ghost anymore.

Part Four

The Registry Center was born without ceremony. No ribbon-cutting, no speeches, no glossy brochure photos of smiling officials. Just a rented floor in an aging downtown building, a donated set of desks, and a staff that believed, almost to the point of naiveté, that paperwork could be a battleground for justice.

The first day we opened, the elevator stuck between floors.

Sophie and I sat on the gray carpet, our backs against opposite walls, the emergency stop button glowing like a joke between us.

“Symbolic,” Sophie said. “We try to go up, the system panics and traps us.”

“At least there’s phone reception,” I answered, holding my cell up like a flag. “I’d hate to have my second death be in an elevator.”

She snorted. “Too on the nose.”

Maintenance got us out eventually, prying the doors open to reveal the half-lit hallway of the ninth floor. It smelled like old paper and coffee. The Registry Center’s logo was taped to the door—a placeholder sign until we could afford something more permanent. A small, dark-haired woman stood in the corridor, clutching a manila folder to her chest.

“Are you…” she began, reading the sign again as if hoping it might say something else. “…the place that helps with, um, identity… mistakes?”

“Sometimes they’re mistakes,” I said, stepping out of the elevator. “Sometimes they’re not. Come in.”

Her name was Maribel.

She was thirty-six, a dental hygienist from a suburb where cul-de-sacs curled like question marks. Her ex-husband had been charming in the way of men who practice charm on everyone but their conscience. He’d taken out a life insurance policy on her, then, on a Tuesday like any other, filed a death certificate. She discovered she was dead when her debit card stopped working and the bank told her the account belonged to an estate.

“I went to the clerk’s office,” she said, sitting at the secondhand conference table we’d salvaged from a bankruptcy auction. “They told me there must’ve been a typo. I showed them my driver’s license, my Social Security card, my face.” She pointed at herself as if her existence were a PowerPoint slide. “They shrugged. Said, ‘Sometimes the database takes a while to catch up.’”

Her ex-husband had vanished. The insurance company claimed they’d acted in good faith. The police were interested, but only in the way overworked detectives are interested in white-collar crime: academically, with a sigh.

To Maribel, the cruelty wasn’t just the money. It was the surreal experience of being treated like a glitch in her own life. Her utilities refused to start new service because the system flagged her as deceased. Her employer’s HR department had suspended her benefits “pending clarification.” Her mother, deeply religious and deeply gullible, had wondered aloud if this was some “sign from above.”

“I don’t know what to do,” Maribel finished. “Someone needs to tell them I’m not gone.”

“I believe you,” I said. “You’re the most alive person in this building.”

She laughed, but tears slipped sideways down her cheeks.

We took her file apart the way a mechanic disassembles an engine. Sophie traced the insurance forms; I examined the death certificate.

The doctor’s name at the bottom made my blood thrum.

It was familiar.

Not in the way a celebrity’s name is familiar, or an old classmate’s. In the way a ghost’s footprint is familiar. The angled signature, the looping D.

This was the same physician who had “signed” my death certificate.

Retired now. Living two states away. Notorious, Sophie’s notes on my case had said, for signing forms without examining bodies. There’d been talk of charges back when my story exploded, but the prosecutors had gone after bigger game—my father, Daniel, the lawyer. The doctor had faded into the background, a footnote in a scandal people had been eager to move past.

Sophie’s eyes met mine over the paper.

“Well,” she said. “Either the universe doesn’t have much imagination, or we’ve stumbled into a franchise.”

Anger punched through me, sharp and hot. All the work we’d done—the hearings, the audits, the trust, my father’s conviction—and still the same signature could be used like a guillotine on another woman’s life.

“This isn’t just about Maribel,” I said. “This is a pattern.”

Patterns are what systems pay attention to—regulators, journalists, courts. A single forged certificate can be dismissed as a clerical oddity. Two, with the same signatory and the same financial trail, begin to look like policy.

We dug.

Sophie pulled old disciplinary records from medical boards. I filed public-records requests for death certificates bearing the same doctor’s name. We brought in a young attorney named Khalil, fresh from law school and vibrating with the righteous fervor of someone who hadn’t yet been taught to lower his expectations.

Within weeks, we had six more cases on our desks.

A man whose “death” had allowed his business partner to liquidate a company and walk away with the assets. An elderly woman whose “passing” had triggered a will she didn’t remember signing, funneling her house into the hands of a nephew with debts. A farm worker whose so-called death had enabled a labor contractor to collect a payout and leave his family undocumented and stranded.

In some, the doctor’s signature was genuine. In others, it looked forged. In all, the bodies in question were very much alive, walking around in a country that had already started to forget them.

The Registry Center became a hive. Phones rang. Emails stacked up. Volunteers appeared—law students, retired paralegals, a data analyst who insisted on building us a tracking system so we wouldn’t drown in our own evidence. We partnered with legal clinics, immigrant advocacy groups, veteran services. Names poured in, each attached to a story that should have been unremarkable but had been twisted into something grotesque.

One night, long after the building’s other tenants had gone home, I sat at my desk and flipped through copies of death certificates, all bearing familiar shapes: my own, Maribel’s, the others. The heading—STATE OF—looked so official at the top of each. The seal, embossed. The language, solemn. It was astonishing how much power a piece of paper had when everyone agreed it meant something.

“This is bigger than us now,” Khalil said, appearing in my doorway with a stack of takeout containers. “You know that, right?”

“That’s the most terrifying sentence I’ve heard all week,” I replied. “And we’ve been interviewing people who found out they were dead from collection calls.”

He set the food down and leaned against the doorframe. “We could file these one by one. Case by case. Win some, lose some. Maybe get the doctor’s license revoked, maybe push an insurance company into a settlement. Or…”

“Or we build a bonfire,” I said, finishing his thought.

“Exactly,” he said. “We take the pattern to the state attorney general. To the feds. To the press. They listened when you walked into that courtroom alive. They’ll listen now.”

The idea of going public again made something in me recoil. The last time my story hit the news, my face had been plastered on screens with headlines that alternated between awe and gawking. SURPRISE HEIR RETURNS FROM THE DEAD. BUSINESS TYCOON FAKES DAUGHTER’S DEMISE. I had become both symbol and spectacle, my actual life flattened into a morality play.

I had used that spectacle then because I’d had no choice. Now, I did.

“Do we really want cameras back in our faces?” I asked.

“This isn’t about your father anymore,” Sophie said, joining us with her laptop under one arm. “This is about the system that let him do what he did—and is still letting others do it. If we stay quiet, we become what he wanted you to be.”

A ghost.

The word didn’t need to be spoken.

We drafted a report. Not a manifesto, not a melodrama. A document with charts and timelines, with appendices and references and a tone that said: We are not hysterical; we are precise. We mapped the web of signatures, the correlations with payouts, the timelines where people’s lives had been suspended while their paperwork argued otherwise.

When it was done, we sent it to three places at once.

The state attorney general’s office.

The Office of the Inspector General overseeing federal benefit systems.

And a journalist I had come to trust more than most—Elena Cortez, the investigative reporter who had covered my original case with uncommon restraint. She had been the only one who’d asked, on air, “What happens to someone’s sense of self when a government document says they no longer exist?”

Her reply arrived within hours: I’m coming by tomorrow. Don’t clean your office. Audiences trust messy.

She brought a camera crew that smelled of coffee and exhaustion. We cleared a spare desk for her to set up on, and while her team fussed with lights and cables, she sat with me, Maribel, and two other clients in the conference room.

“I know what they did to you,” she said to me. “But I want to talk about what you’re doing now. About why you came back to the same battlefield.”

“I didn’t come back,” I said. “The battlefield moved to where I was standing.”

Maribel told her story, her hands knotting and unknotting on the table. A retired teacher named Harold described how his pension payments had stopped because, in some system, a checkbox had been flipped from LIVING to DECEASED.

“My granddaughter tried to open a TikTok account for me,” he said. “The app said I wasn’t eligible because I was dead. That’s how I found out.”

Elena listened, her pen scratching across her notebook.

“This doesn’t fit neatly into most narratives,” she said after the camera crew had stepped out. “It’s not just one villain. It’s greedy exes, sloppy doctors, overworked bureaucrats, opportunistic corporations. A hydra.”

“That’s why we have to cut off the head we can see,” I said. “If the doctor hadn’t treated his pen like a weapon, none of this would have happened. If the systems that rely on his signature didn’t treat it as gospel, none of this would have stuck.”

Her story aired a week later.

She didn’t start with me. She started with Harold trying to convince a call center that he was eligible for his own birthday discount. With Maribel arguing with a clerk about turning her water back on. With an immigrant father whose son couldn’t enroll in school because the system insisted his father was deceased.

Then, gently, she folded my story in. Not as a headliner, but as an origin point. The scandal-that-was, now spilling into the scandal-that-still-is.

The next morning, our phones exploded.

Calls from people in other states, other cities. Emails from lawyers, from advocacy groups, from a woman who ran a support group for people defrauded by their own families. Then, less expected, a terse voicemail from an assistant in the attorney general’s office:

We’ve reviewed your report and the accompanying media coverage. Our office will be opening a formal investigation into fraudulent death certifications and associated financial crimes. We request a meeting at your earliest convenience.

I played that message three times, just to savor the words formal investigation.

This time, when I walked into a government building, I did so not as a ghost crashing my own funeral, but as an expert witness.

The conference room was bland in the way public offices specialize in: neutral walls, a table that had seen too many elbows, a speakerphone that looked like a small spaceship. The deputy attorney general was a woman in her fifties with sharp eyes and a tired expression. She shook my hand, then Sophie’s, then Khalil’s.

“I remember watching coverage of your case,” she said to me. “I was in a different division then. That death certificate should have been a one-time scandal. The fact that we’re here again means we missed something.”

“What you missed,” I said gently, “was how profitable erasing someone could be.”

They asked us questions—for hours. About methods, about cases, about how we’d found the overlapping patterns. About the doctor, whose name underwrote so many of the lies.

“He’s old,” one of the investigators said. “Retired. He’ll say he was pressured, that he needed money, that he didn’t ‘understand the implications.’ Juries like old men who look confused.”

“Then don’t start with him,” I said. “Start with the companies. The insurers, the banks, the partners who benefited. He’s the pen. They’re the hand.”

The deputy attorney general’s eyes sharpened. “You’ve thought this through,” she said.

“Being declared dead gives you a lot of time to think,” I replied.

In the months that followed, subpoenas went out like seeds on the wind. Some fell on barren ground. Others landed where they could grow.

The doctor was deposed again, this time not as a footnote, but as a focal point. He stammered, pleaded foggy memory, muttered about just wanting to help families “move on.” His lawyer talked about “paper irregularities” and “regrettable misunderstandings.”

But alongside his trembling words were rows of data, lines of money leaking into accounts that had no business existing. The insurers, suddenly faced with the prospect of criminal liability, turned from stone walls into sieves. Emails surfaced. Memos about “expediting claims” in cases where “medical signoff is already secured.” Internal jokes about “ghost clients.”

Sitting in the back of those hearings, I felt a strange detachment. This was, in many ways, a sequel to my own drama. Same signature, different stage. But this time, I wasn’t the one on the stand. I was in the notes, in the footnotes, in the precedents the prosecutors cited.

It was messy. It was slow. It was never as cinematic as the first time I walked into a courtroom alive. No one gasped in unison. No judge asked who I was.

But something deeper shifted.

Policies changed. States noticed each other noticing. Databases began cross-checking death reports against multiple sources before shutting down someone’s life. Medical boards rewrote their guidelines. Insurers instituted extra verification steps for high-value payouts.

Layers. None of them perfect. All of them better than before.

At the Registry Center, we celebrated those bureaucratic victories the way other offices celebrated birthdays—with cake in the break room and a flurry of emails that said, Look. Look what persistence did.

One evening, as we were packing up, Maribel lingered by my office door.

“Do you ever think about how different your life would have been if your father had, I don’t know, just… asked for help?” she said.

“All the time,” I answered.

“What would you have done?”

“If he’d been honest? If he’d said, ‘I’m scared, the company is shaky, I made some bad calls, help me untangle this’?” I considered. “I probably would have told him to hire someone like Sophie ten years earlier and to stop treating money like a personality trait.”

She laughed. Then her face sobered.

“You know, when I first came here, I just wanted my water turned back on,” she said. “Now they’re quoting me in hearings. My mom keeps cutting out newspaper clippings and putting them on her fridge.”

“You’re more than a case,” I said. “You’re a precedent.”

She took that in, then shook her head with a half-smile. “I’m also tired,” she said. “But a good tired.”

“Me too,” I said.

As the lights clicked off, the city beyond the windows glowed with its own dramas—sirens, lullabies, arguments in kitchens, whispered apologies. Somewhere, someone was signing a document that would change another person’s life. Maybe for good. Maybe not.

All I could do was keep watch over the corner of the world I’d staked out: the thin line where a name meets a piece of paper and decides which one is stronger.

Part Five

My father died three years after the Registry Center opened.

The call came on a Wednesday, the kind of midweek day the universe uses for announcements that don’t want to compete with holidays. I was in a workshop with a group of social workers, explaining how to spot the warning signs of identity manipulation in their clients’ paperwork. My phone buzzed in my pocket; I ignored it. It buzzed again. And again.

During a break, I checked.

Three missed calls from an unknown number, one voicemail.

This is the medical supervisor at Clearwater Correctional Facility. Please contact us regarding inmate number—

For a moment, my body reverted to old habits. Courtrooms, gulps of air that wouldn’t go all the way in, the sound of a gavel. Then my rational mind caught up.

I stepped into the hallway and called back.

“Ms.—” the supervisor consulted something, mispronouncing my last name with professional politeness. “I’m sorry to inform you that your father passed away this morning. It appears to have been a heart attack. He was transported to the hospital but could not be resuscitated.”

The words hung in the air between the fluorescent lights and my ear.

“Okay,” I said, because what else do you say when informed that the man who once purchased your legal death has now died a legal death of his own?

“We need to know your wishes regarding the body,” the supervisor continued. “As next of kin, you’re listed as the primary contact.”

Of course I was. Systems love circular irony.

“I’ll… talk to my family,” I said. “I’ll call you back.”

After I hung up, I slid down the wall until I was sitting on the institutional tile floor. My knees didn’t feel like they belonged to me. People walked past with coffee cups and clipboards. No one looked twice. To them, I was just another woman having a hard phone call.

I thought about the first time I’d seen his name on a death certificate—mine. How unreal it had felt, how violently wrong. Now, somewhere, a new document was being drafted. This time, the name and the absence would match.

I didn’t cry. Not then. Grief had been a long, complicated visitor in my life where he was concerned. It had arrived when I first realized he wasn’t the father I’d thought he was, when I’d listened to him testify me out of existence, when I’d walked out of the prison visiting room and left his hand hanging in the air. His physical death felt, in some ways, like paperwork catching up.

Still, there was a weight to it.

I called my mother.

She answered on the second ring. “Sweetheart?” she said, her voice cautious, as if expecting protestors or reporters to have somehow tunneled into her landline.

“He’s gone,” I said.

Silence. Then a small exhale, like the sound of a balloon losing air.

“Oh,” she said. “Oh.”

I could picture her in the kitchen of her condo—the one she’d moved into after selling the family house, the one with potted herbs on the windowsill and magnets from every place she’d traveled post-scandal, as if geography could erase history.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“I don’t know yet,” she said honestly. “I thought… I thought I’d be prepared. After everything. But death is so… final.”

“Paperwork loves final,” I said automatically.

She made a wet, choked sound that might have been a laugh. “He always thought he could negotiate his way out of everything,” she said. “I suppose this is the first deal he can’t amend.”

We arranged a small funeral.

No cameras. No business associates giving eulogies about his “vision” or “tenacity.” The old board members sent flowers. Some sent terse notes: He was a complicated man. Aren’t we all? Others sent nothing at all.

In the end, the group that gathered at the cemetery was small: my mother, myself, my son, a few distant relatives still willing to be seen in public with our last name, and Sophie, who came because she understood that numbers aren’t the only things worth auditing.

The sky was appropriately undecided—thin clouds, pale sun, the weather of noncommittal grief.

The preacher, a man who’d clearly never met my father, said the things preachers say when handed a script and a widow who insists on something “simple.” He spoke of forgiveness, of the mystery of God’s plan, of the hope of redemption. My mother stared at the casket with the brittle posture of someone holding too many memories in place.

When it was my turn to speak, I walked up to the small podium, my shoes sinking slightly into the already disturbed earth.

“I’m not here to rewrite his life,” I said. “Or to pretend it was something it wasn’t. My father did terrible things. He hurt people. He hurt me. He let money and fear and ego rearrange his priorities until his own daughter became, to him, a column in an accounting problem.”

A breeze ruffled the edges of the program in my hand. My son watched me with wide eyes, as if collecting data for the day he might have to stand over my grave and decide what to say.

“But he also taught me to read a balance sheet before I could drive,” I continued. “He taught me that showing up prepared is a kindness to other people’s time. And, accidentally, he taught me that our names matter more than any number in any ledger.”

I thought of the last time I’d seen him, how small he’d looked, how his hand had hovered over the table like a question he was afraid to ask.

“I can’t forgive the choices he made,” I said. “But I can choose what to do with what I learned surviving them. And I choose, today, not to let his worst act be the only story we tell about this family.”

I stepped back. The preacher murmured something closing and official. The casket was lowered. My mother threw in a single white rose. My son tossed in a rock he’d picked up from the path on the way in because, as he whispered to me, “He liked things that weighed a lot.”

After the funeral, people drifted back to their cars with the awkward half-hugs of mourners unsure how sad they’re supposed to be.

My mother and I lingered.

“Do you want to see something?” she asked, her lipstick smeared just enough to break my heart.

“Sure,” I said.

She reached into her purse and pulled out an envelope. Inside was a piece of paper, creased and yellowed at the edges.

For a split second, my stomach clenched. A death certificate. I’d know the layout anywhere.

But this one was different.

It was a birth certificate. Mine. The original, the one from the hospital where I’d come screaming into the world. It had my name, my mother’s name, my father’s, all in type that had long since gone out of fashion. At the bottom, in the doctor’s handwriting, a comment: healthy lungs, loud.

“I found it when I was going through boxes last week,” my mother said. “I’d forgotten I had it. Thought you might want the official proof that, before any scheme, you were born. Loudly.”

I traced the letters with my finger. The ink was faded, but the assertion was as strong as ever: I existed.

“Thank you,” I said.

That night, at home, I pulled out the other document I still had: a certified copy of the annulled death certificate. The one that had started everything. In its corner, in red ink, the word VOID had been stamped over the seal like a scar.

I placed the two documents side by side on my kitchen table.

Birth.

Void.

One said I had arrived. The other acknowledged that someone had tried, and failed, to make that arrival irrelevant.

My son came in, sweaty from a game of pickup basketball with his friends.

“What’s this?” he asked, leaning over my shoulder.

“Proof,” I said. “Of a before and an almost-after.”

He studied them, then looked at me. “Are you going to keep these?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “But not in a box where only I can see them.”

The next week, I donated the annulled death certificate—names redacted, sensitive details obscured—to the small museum area we were putting together in the lobby of the Registry Center.

We called the exhibit Paper Lives.

There were framed copies of other documents: a Social Security statement that had marked a man as deceased, a pension letter returned with “ADDRESSEE UNKNOWN,” a driver’s license stamped INVALID across the face of someone very much alive. Under each, a small plaque told the story not of the paperwork, but of the person.

Mine sat in the center. The caption was simple:

This certificate declared its subject dead so others could profit. She disagreed.

Visitors wandered through, some with professional interest, some with personal. I watched their faces as they paused at various frames, the way their brows furrowed, the way their jaws set.

“It’s just paper,” one teenage girl muttered to her friend.

“So is money,” her friend replied.

One afternoon, as I was refilling the pamphlet stand, a man in a suit hovered near my exhibit longer than most. Late forties, maybe, with the kind of haircut that spoke of corporate barbers and calendar reminders.

“Is this… you?” he asked, gesturing at the redacted document.

“Yes,” I said.

He nodded slowly. “My father left everything to my brother,” he said. “Didn’t fake my death or anything, just pretended I wasn’t worth mentioning in his will. Sometimes I wonder which is worse.”

I thought about that.

“I don’t think pain comes with a ranking system,” I said. “Only with choices about what we do after.”

He smiled, a short, crooked thing. “Fair enough,” he said, and moved on.

The Registry Center grew.

We opened a second location in another state, then a third. We trained social workers and legal advocates, built online tools for people to check their records, lobbied for legislation that would require multiple points of verification before a death could be recorded.

Some nights, the work felt like bailing water from a boat with a colander. For every victory, there were ten new stories of people being swallowed by someone else’s paperwork. But we kept going, driven not by the illusion that we could fix everything, but by the stubborn insistence that we could fix something.

On the anniversary of my father’s death, my son and I went back to the lake where I’d dared him, as a teenager, to jump into the water in his suit. The dock was still rickety. The water still smelled faintly of algae and summer.

“Did he really jump?” my son asked, toes hanging over the edge.

“He did,” I said. “Complained about it the whole time, but he did.”

My son glanced at me sideways. “Are you ever going to tell me his good stories?” he asked. “Not just the bad ones?”

The question surprised me. I realized I had been so careful not to glorify my father’s power that I’d neglected to describe his softness.

“He used to sing off-key in the car,” I said slowly. “Terribly. But he’d do all the voices in the songs. And he made the best pancakes. He’d shape them like animals, even when he was late for work. And once, when I broke my arm falling out of a tree, he carried me two blocks to the car because I refused to let anyone call an ambulance. Said if I wanted to be dramatic, I had to commit.”

My son grinned. “Sounds like you,” he said.

“Unfortunately,” I replied.

We sat in comfortable silence for a while, the water slapping against the pylons beneath us.

“Mom?” he said.

“Yeah?”

“Do you ever get scared it could happen again? To you, or to me?”

The fear was there, of course. It lived in the background like a low-grade fever. Every time the mail brought a letter from a government agency, every time a bank asked for “verification,” a small part of me braced for the universe to declare, once again, that I was gone.

But I had learned something important in the years since I’d walked into that courtroom alive.

“Yes,” I said. “Sometimes I do get scared. Systems are big. People can be greedy or careless. Mistakes happen. But here’s the difference now: we know what to look for. We know where the cracks are. And there are more of us watching.”

“Like superheroes, but with paper,” he said.

“Exactly,” I said. “Bureaucratic Avengers.”

He laughed, then nudged my shoulder with his.

“I’m glad you didn’t stay dead,” he said.

“Me too,” I replied. “It would have really messed up your college applications.”

He rolled his eyes, but the relief in his smile was real.

As the sun dipped lower, turning the water copper, I thought back to the first time the room stopped breathing when I walked in. How every eye had turned to me, not as a daughter or a neighbor or a woman who liked coffee too strong, but as an anomaly. A disruption. A ghost who refused to behave.

Life now was less dramatic. No gavel, no headlines, no collective gasp.

Instead, I had emails to answer, staff meetings to attend, a teenager to nag about homework, a mother to check in on, an aging cat to take to the vet. My days were filled with forms and phone calls, with people crying in my office, with small celebrations over incremental policy changes.

It was, in other words, a life.

And that, ultimately, was the clearest ending I could have asked for. Not a climactic showdown, not a Hollywood freeze-frame, but the stubborn continuation of ordinary days in the face of those who had tried to deny them.

Some nights, when the house was quiet and the only sound was the hum of the refrigerator and my own breath, I’d whisper into the dark, just to hear the line reversed:

“She’s dead,” my father had said under oath.

“No,” the years answered. “She’s not.”

The death certificate had carried my name, but it had failed to carry my story.

They’d moved six million dollars into an offshore account to buy silence, to pay for my absence, to tidy away the inconvenience of my existence. In the end, that money had built scholarships, funded legal aid, kept lights on in offices where other people learned they were not as erasable as someone had hoped.

The room had stopped breathing when I first walked in alive.

Now, when I walked into rooms—courtrooms, classrooms, conference halls—they kept breathing. People shifted their chairs, checked their phones, sipped their coffee. I was, at last, just another person at the table. Present. Accounted for.

And in a world where paper can kill you, being ordinary and undeniable is the most dramatic thing of all.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My stepson thought it was funny to tell his girlfriend I was “clingy” and “desperate for his approval.”

My stepson thought it was funny to tell his girlfriend I was “clingy” and “desperate for his approval.” So I…

“Get out & never come back!” — My parents said. So I left without a word.

“Get out & never come back!” — My parents said. So I left without a word. Three months later, Dad…

My SIL and Her Husband Bullied Me Every Day! But When They Found Out Who They Were Dealing With…

My SIL and Her Husband Bullied Me Every Day! But When They Found Out Who They Were Dealing With… Part…

Married 5 Years, I Found My Husband Cheating Mistress, So I Left With Kid & Wed CEO—Now He’s Gone Mad!

Married 5 Years, I Found My Husband Cheating Mistress, So I Left With Kid & Wed CEO—Now He’s Gone Mad!…

She shaved my daughter’s head at a family party and laughed, calling it a “prank.”

She shaved my daughter’s head at a family party and laughed, calling it a “prank.” They all thought I was…

HOA Illegally Sold My 1500 Acres—So I Turned Around and Sold Their Homes Legally

HOA Illegally Sold My 1500 Acres—So I Turned Around and Sold Their Homes Legally Part 1 By the time…

End of content

No more pages to load