“She’s Alive,” I Whispered When I Saw the Photo of the Tycoon’s Deceased Daughter—But Why…

Part One

The July heat clung to me like a suffocating blanket as I sat on a cracked bench near the bus stop. The pavement shimmered in waves. My canvas bag—the last neat remnant of a life that had shrugged me off—rested against my ankle. Three nights without a roof had pared me back to need: water, shade, a plan I could execute with the strength I had left.

A year ago I wore white sneakers and a clipped badge and a smile people trusted. Nurse: the word used to fit my mouth. Then the private clinic in New Haven chose a scapegoat when a patient died on a table that wasn’t ready. Courts drained my savings to a stain. Rumor accomplished the rest. By the time my father’s lungs turned traitor, I sold our little apartment to buy him time I could count in days, not months. When he was gone, the silence arrived like weather and refused to leave.

He had, however, left me one stubborn thing: a letter. Not to me—my father was a proud man who found it easier to love with hands than with words—but to someone he had told me snippets about when we were both younger versions of ourselves. Richard Thompson—boyhood ally, teenage co-conspirator, the friend who left town in a suit when my father stayed behind with a toolbox. Pride had kept them apart. Dying taught my father what pride couldn’t. In tough, square handwriting he wrote Richard and asked him not to let his daughter fall through a world that doesn’t notice when women do.

The envelope had gone soft at the folds where I had pressed it open and shut in cheap motel light. The address on a slip of paper felt like a dare: Greenwich, Connecticut. Old money. Old brick. Iron gates that swing because someone presses a button, not because someone sweats.

I washed my face in a bus-station sink and made the hour count. I rehearsed a posture that didn’t apologize. At 2:00 my watch told me I’d make the three o’clock if I didn’t flinch. I stood, hitched the strap higher on my shoulder, and boarded a bus that might as well have been a border crossing.

Greenwich wears wealth the way some people wear a family ring—unconscious, unashamed, older than the conversation. The Thompson gates opened as quietly as an agreement lawyers had already signed. A man in navy with the precise politeness of someone paid to notice the wrong things escorted me through a hall where oil portraits watched without blinking.

Richard Thompson stood when I entered his study. He moved like a man who had learned to enter rooms as if he expected them to be his. Gray at the temples. A face that had spent as much time learning not to show emotion as it had learning how to win deals. When he took my hand, his grip surprised me: warm, human.

“Miss Whitaker,” he said. “I’m glad you came.”

I handed him the letter with fingers that wanted to shake and told them not to. He read, mouth tightening at the corners once, the way a man tightens a rope when a knot slips and he won’t let it.

“I wish I had known,” he said. “Your father was—” He searched the ceiling for a word the ceiling would approve. “—a proud man.”

So I told him the rest: the clinic, the courtroom, the ward where my father learned to count oxygen in seconds, the garage sale that had turned my life into other people’s bargains. I told it without the edges serrated by pity. He listened the way men like him rarely do, with his phone flat on the desk and his eyes on my face.

“You trained as a nurse,” he said finally. “I need one.”

For a moment I thought the heat had made me hear wrong. He explained: his father, Charles Thompson, stroke six months ago; progress visible but fragile; caregivers who melt away like snow when spring arrives. “He is exacting,” Richard added, which is the word men like him use when they mean difficult but can’t bring themselves to say it. “He’s also…lonely. Work here. Live here. Be compensated fairly.” The offer fell between us like cold water after a desert.

I thought of the bench I had slept on and the way my bones woke me before dawn to remind me they hated concrete. I thought of my father’s handwriting and the way his hands had knelt under sinks so I could stand in white shoes and call myself nurse. “Yes,” I said, before the part of me that had learned to be suspicious could clear its throat.

They took me upstairs to meet the man who would test the promise we had just made.

Charles sat by a window with his back to the light, which meant the first time I saw his eyes they were shadow and the last time I saw his mouth it was not smiling. Silver hair combed with the same discipline he had once demanded of younger men. A cane leaned against a table he probably hated. His voice could have cut glass.

“So,” he said, without preface, “you’re the one who’s supposed to keep me alive. Another jailer.” I said my name and reached for the part of me that had held hands in emergency rooms and told strangers they could, in fact, keep breathing. His gaze went down to my shoes and back up to my face. A huff that might have been laughter. “At least you’re not dull to look at,” he said. “The last one looked like someone had pickled her.”

“Father,” Richard said sharply. “Enough.”

“Good,” Charles said, eyes on me. “You have a spine. We’ll get along.”

Dinner that evening unfolded under a chandelier and a portrait. We were four: Richard at the head as if gravity happened there; Charles to his right, brittle and brilliant; a woman introduced as Margaret Thompson—Richard’s aunt, retired contralto, posture like a moral; and me, seat assigned by the housekeeper as if chairs know where they are supposed to go. Margaret asked questions that could have drawn blood and didn’t. She had the kind of listening face that makes people tell the next thing they didn’t intend to.

The room they gave me afterward had linen that snapped when you shook it and a window that overlooked roses laid out like an apology. I pressed my palms to the duvet to make sure it was real. It was. I slept without hearing footsteps for the first time in three nights.

The house learned my pace. I learned which stairs complained and which doors didn’t. Charles tested me with barbed sentences and the kind of sarcasm someone uses when he once commanded and misses the echo. We struck a truce: I wouldn’t pretend he wasn’t infuriating; he wouldn’t pretend he didn’t need me.

On a day when even the rain refused drama, I found the photograph.

A silver frame sat on Charles’s desk with the deliberateness of an altar. In it, a young woman looked out—chin a thesis on stubbornness, eyes with that glitter that makes love both possible and terrifying. The nameplate below had been polished so hard I could see my city-worn face in it.

Catherine Thompson.

Katie. The daughter who had died in a car that later burned hard enough to convince a coroner. The girl whose funeral this house still attended every time the light fell a certain way.

My fingers knew before my mind did. I leaned in. Scar on the left wrist, faint even in shadow. A tilt to the mouth like someone about to say something you’d better pay attention to. My chest went cold because I had seen that face before—without the hair, without the gloss. I had seen it behind a locked ward’s wired glass, eyes dulled by medication, a name mispronounced by a tired nurse: Yevdokia. Yevdozia. She had rarely looked up. When she did, she looked at me like she couldn’t fit words together but still had something that needed to leave her mouth before it strangled her.

The photograph and the memory argued. The scar ended the fight.

I left the study and closed the door as if loudness could wake the dead.

In the kitchen, lit by a summer that refused to give up the day, I opened a laptop with fingers that thought better of it. Articles conjured themselves: Tragic Fire Claims Tycoon’s Daughter. Dental Records Confirm Identity. A picture of twisted metal. A photograph of Richard in a suit that looked heavier than grief.

I called the psychiatric hospital where I had once memorized the night shift’s timings by the temperature of my coffee. The receptionist heard my name and softened. “I’m looking for a former patient,” I said, keeping my voice between apologetic and bored. “Yevdokia…admitted roughly six months before I left. Research.”

Paper shuffled. Voices murmured. And then: “She’s no longer here. Discharged not long after you left. Guardian signed her out.” The voice dropped. “A man. Well connected. Name was…Griffin. Alex Griffin.”

The name fell into the study like a duffel bag. Alex Griffin—Richard’s partner, smile like a campaign poster, hands like a cabinet you wouldn’t know how to open until it was too late.

The world narrowed to a corridor. I saw pieces, and then I saw the picture they made. The car fire that did not require a body that looks like a daughter if a dentist signs off. The partner who moves money and people with equal skill. The girl’s diary I had not yet found but could already hear: If something happens to me, it won’t be an accident.

I did not sleep. In the morning, the roses looked like blood.

Catherine’s old room had been staged like a museum you visit to pretend grief can be tidied. Books aligned to spines. A scarf across a chair as if she had just left to answer a call. I opened a desk drawer that stuck at the inch where secrets live and pulled out a leather notebook worn in the places hands love most.

Her writing slanted like a girl accustomed to writing in motion. Ink bled where tears must have fallen or where she wrote too fast for the pen to keep up. I know what they’re doing. Forged contracts. Father trusts me more than anyone. I’ll show him. Later: Confronted Alex. Smile wrong. Anthony pretending innocence. Heard them in the study. If I don’t stop them— and then a line that made me put the book down because my hands had started to shake. If I push harder, they will make me disappear.

The day we call the accident happened a page later. The journal ended with a notation that could have been a date or a gasp.

I found Charles in the study that evening staring at the fireplace the way a man stares at a mirror when he wants it to lie. I told him what I had found and didn’t pretend gentleness. He did not flinch as much as I expected.

“She argued with Alex the week before,” he said without turning. “She told me she hated that road. But later someone said that’s where she…went off. She would not have driven there out of choice.”

The night let the words sit in it for a while. I heard gravel in the drive the next morning before the housekeeper opened the curtains. I watched from the edge of a shadow as two men crossed marble like it was theirs: Griffin and Anthony Meyers. Sharks that had learned to wear suits.

Richard met them with a smile that had been filed down. Their voices talked about deals as if deals were people. And then, as if I had asked the air to speak, I heard him admit in a tone he probably hadn’t used since his daughter learned to walk: “She told me she had found documents that didn’t make sense. She wanted to show me. She was going to.”

Griffin’s mouth did something that wasn’t a smile. “The past is best left buried,” he said. “She was…impulsive.”

Anthony stared at the carpet like numbers appear if you look long enough. I pressed my back to the banister until it hurt. The photograph in the silver frame had begun to whisper. I did what women who are tired of being rooms do: I started making a list.

Call Marina.

We had worked nights together once, trading granola bars and jokes at two in the morning to keep from crying. She had a memory for files like other people have for songs. When she answered my call she laughed the way you laugh when the past shows up without knocking.

“I need a record,” I said. “Yevdokia. Admission. Discharge. Guardian.”

“You know I could lose my license for this,” she said, because she is both brave and practical.

“I know,” I said. “I am asking because someone else already has.”

She sighed the sigh nurses sigh when the world asks them to clean up a mess it created. “I’ll call you.”

I started copying pages. I started backing up files. I started noticing the car idling too long at the end of the drive and the silhouette that lingered outside the kitchen window before the porch light snapped it away.

That night I wrote the sentence that would save me. There’s no turning back.

Part Two

Marina called two days later with a voice that was both triumph and fear. “The file’s thin,” she said. “Which is interesting because that place loves paperwork more than it loves people. Admit under the name Yevdokia Morozova—no ID, no history. Discharged under court order. Guardian Alex Griffin. Here’s where it gets weird: the discharge packet includes a lab requisition for a DNA assay that was never processed. The dentist name on the death report? Same one who signs off on the ‘accident’ identification. Same signature. Different handwriting.”

She sent scans. I printed them and pressed the warm paper to the diary and said Catherine’s name aloud in a house that had stopped doing that. I let the living room become a table. Photographs. Ledger copies. A map. A sharpened pencil. I drew lines between people and the lines thickened into ropes.

Richard found me there the way men find a thing they didn’t know they were ready to see. He sank into a chair and put his head in his hands. He did not cry; men like him don’t until it’s too late. He did, however, tell me something he probably hadn’t let himself say: “I failed her.”

“You trusted the wrong people,” I said. “And they taught you to trust them.”

He lifted his head. “What do we do?”

“First, we make them say her name in a place where lies go on record.” I had been a nurse long enough to know that you don’t save a patient by wishing. You document. You testify. You drag the facts into the light and make them squint.

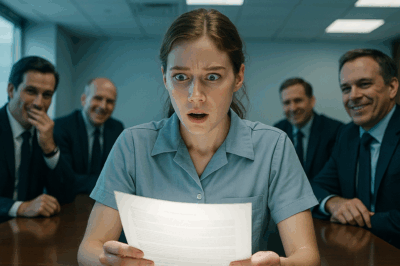

I walked into the district attorney’s office with a file so heavy it forced the young ADA to take me seriously even before I told him what it contained. I knew the language to use: pattern, forgery, coercion, wrongful death. I watched his eyebrows learn from his eyes. When he asked, “Can you produce a witness?” I did not say victim. I said, “Survivor.”

The emergency petition landed on a Family Court docket because that’s where you file when you argue that a death certificate tells the wrong story and a living woman has been deprived of her name. The judge assigned to the hearing was one of those women the law produces every now and then like a miracle: precise, bored by men who try to charm her, respectful of the time of people who have had theirs wasted.

Griffin’s lawyers tried to move the hearing, delay it, drown us in motions written to sound important. The judge gave them deadlines and side-eye. “Produce the ward known as Yevdokia,” she wrote on an order, “or explain, under oath, why you cannot.” I slept for the first time in a week.

We had forty-eight hours to find her. That turned out to be enough only because greed makes men lazy. Marina’s cousin at the psychiatric hospital had a friend at a private rehab that had a side hustle in convalescence for people who had enough money to be dangerously inconvenient. She texted me an address and a warning: They’ll deny it. Bring a court order. Bring a police escort. Bring someone who knows how to breathe when people lie to their face.

Richard called a security chief he trusted because the man had saved him from a mistake once and charged him double for the privilege. We drove to the facility like a timeline coming for a secret. The receptionist smiled with the flat brightness of a person paid to lie. The director—a man with silver hair and a doctor’s coat that hadn’t seen a patient in years—said phrases like “privacy” and “best practices” and “no such person.”

A uniformed officer handed him the judge’s order without blinking. He read it. He smiled like a man who had rehearsed smiling in the mirror. He stepped aside.

They brought her down an elevator that smelled like disinfectant and secrets. She was thinner than when I’d last seen her behind wired glass. Her hair was clean now and bluntly cut. Her eyes weren’t haunted anymore. They were wary. A staff member pushed the wheelchair like she was transporting a case file. I knelt so we could look at each other from the same place in the air.

“Catherine,” I said softly. “I’m Anna. You knew me once as…no one at all. But I knew you.” Her eyes flicked, puzzled. I held out the leather diary, a page folded to a sentence she had written for a future she didn’t expect to reach. She read. Her hand rose to her wrist, to the scar that told the truth when papers did not. She whispered without moving her mouth: “My name is Katie.”

We walked her out under order and stare. Griffin’s car turned the corner a minute too late. His face tried a smile that remembered how and couldn’t manage the trick.

The judge moved the hearing to the largest courtroom because news likes a theater and the public likes a redemption. The town that had mourned a daughter came to watch a rumor become a resurrection. Press sat on the edges like cats.

The opening felt like any other: docket number, counsel names, a gavel that made men behave. Richard took the stand first and said mistake the way men say sin when they can’t bring themselves to admit the word. Charles, in a suit he had never loved more than his dignity, told the court about the arguments, the contract, the daughter who avoided that road as if it owed her money.

Then the judge nodded to me. I stood. My skirt didn’t wrinkle. My hands didn’t shake. I said my name and my license number and the places I had worked and the night a girl with a scar on her wrist stared through me from a locked ward. I said guardian and order and Alex Griffin and the court record turned those words into geography.

The judge looked at me over the top of her reading glasses. “Do you have anything else, Ms. Whitaker?”

I swallowed and let my eyes travel to the doors at the back of the courtroom. “I do, Your Honor,” I said, and then let out the sentence that had been living in my body since the study and the photograph and the burn of belief. “She’s alive.”

The double doors opened as if the building had practiced for this moment. A court officer rolled the wheelchair down the aisle like a man delivering a verdict. It wasn’t spectacle. It was remedy. The room did what rooms do when a story rearranges their furniture. It inhaled and forgot to exhale.

Griffin’s lawyer stood, sat, and stood again because he had been trained to object when the truth walks in wearing a hospital bracelet. The judge put a palm up and he remembered how to sit. She called a recess while she stole her own breath back.

When we resumed, the court knew how to behave. Katie’s voice was small, but not broken. She said her name the way you say a prayer you are learning again: carefully. She told the judge only what the judge needed to hear. She didn’t perform. The diary did the rest. The discharge papers. The dental report that a lab had quietly shown was cut and paste when you knew how to see it. Marina sat in the back with a face you could pour tea into, steady as winter.

Griffin tried to hiss through his teeth: misidentification, trauma misleads, a nurse with a grudge. The judge said words that live in my favorite part of the law: Order to vacate death certificate. Warrant for custodial interference. Referral to the Attorney General. The court reporter looked like she had wanted to type that sentence for years.

The rest wasn’t swift, because justice rarely is, but it was inevitable. Men who build empires on forged signatures forget that ink stains. A junior accountant with ethics and student loans decided he liked sleeping better than he liked Meyers’s lunch invitations and brought emails to the DA the way a boy brings a seashell to his mother: astonished at what he’s found. The AG’s office convened a grand jury. People who had once practiced their smiles for Griffin practiced their immunity agreements instead. Meyers realized he loved not going to prison more than he loved Griffin. Fraud charges made headlines. Accessory charges made better ones. Griffin’s smile fell off his face and no one offered to pick it up.

The Thompson estate modernized: not in marble, in bylaws. Richard fired the right people and hired the ones who told him news he didn’t like to hear. He didn’t rebuild his company with vengeance. He rebuilt it with audits. Charles learned to apologize in full sentences and watched his goddaughter walk under his lindens and didn’t die of the shock.

And me? I sat in a courtroom where the woman who had once been the house’s ghost said thank you with a squeeze of my fingers that almost fractured bone. The judge asked if the record should reflect a new legal name. Katie smiled like the sun finds a window. “The old one,” she said. “It was never dead. It was stolen.”

When the gavel fell, people in the gallery clapped the way people clap at the end of a play when they know the players were, for once, telling the truth. I looked over at Richard. He had one hand on his father’s shoulder. The other was around the back of the chair where Katie sat. He looked at me and didn’t need English.

It was only when we stepped out into the winter air that the sentence I had been carrying for months returned to me not as a warning but as a benediction. She’s alive.

The house in Greenwich learned a new rhythm after that. Charles insisted on breakfast together because, he said, he had wasted enough dinners. Margaret sang again, softly at first, then stronger, as if the house made better acoustics now. Katie walked the path to the garden with a therapist twice a week until the world stopped looking like a door someone might slam.

Richard built a scholarship in her name for the kind of young woman who notices when the numbers don’t add up and says so even when men with expensive pens frown. He asked me to supervise the program until he found someone smarter, and then we both laughed because we had learned how many smart women the world hides until someone bothers to look.

I took the train to New Haven one spring afternoon and walked into the clinic that had tried to make my name a stain. My reinstatement letter lived on the administrator’s desk like a hostage finally released. An HR woman with kind eyes and a dictionary of euphemisms said miscommunication and closure. I said lawsuit settled and shook her hand. I didn’t need that job anymore. But I took back the letter because you take back what’s yours, even if you put it in a box instead of a badge holder.

Richard pressed an envelope into my hand one morning with a look that said consider it an apology on behalf of every man who didn’t say the words when he should have. Inside was a title deed with my name on it—not to a mansion, not to a statement. To a small carriage house on the edge of the property with light in the places a woman would want to sit and read. It wasn’t payment. It was belonging. I hung my father’s letter in the kitchen there, the fold lines smoothed flat, and lit a candle to the boy I had not brought home, and to the man my son had become.

Sometimes I take the train to the city and sit on a bench with a paper cup and watch people forget how much else there is to be. On a day in winter that smelled like oranges and wool, I saw a young woman on a cracked bench near a bus stop count the minutes between options and decide which one would save her. She had a canvas bag that said last and a face that said enough. I wanted to tell her my story, to press a letter into her hand that would carry her over a gate that would open because someone remembered a promise.

Instead, I bought two coffees, sat down in her heat, and said, “You look like you could use something warm.”

She laughed. It sounded like a bruise letting go. “You have no idea.”

I do, I thought, but I simply handed her the cup and told her the bus routes I keep memorized for moments just like this.

When the sun goes down at the Thompson estate now it doesn’t feel like a mansion deciding who is allowed to breathe. It feels like a large house full of voices that have learned to be honest. Katie often sits by the window where her photograph used to stand alone and reads the lines she once wrote too quickly. Sometimes she sings under her breath. Sometimes I do.

If you ask me what the secret was—the one I kept for twenty years and smiled about in a courtroom where men thought the law was a wall—I’ll tell you this: it was never a weapon. It was a life. It was the sentence I spoke to no one and every one the first time I saw a face I recognized in a place that wanted me to look away.

She’s alive.

So am I.

END!

News

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… CH2

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… …

“Mister, please take my little sister, she’s only six months old and very hungry.” Ethan turned and saw a 7-year-old boy holding a tiny baby close. ch2

The city’s pulse was a frantic drum against Ethan’s ribs. Time was a thief, and it was currently picking his pocket…

The Waitress Said, “My Mother Has the Same Ring.” — The Millionaire Looked at Her and Froze. ch2

Graham Thompson, the 53-year-old founder of Thompson Grand Hotels, sat alone at a corner window table in The Beacon, a warm, wood-paneled…

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… CH2

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… Part One…

My Son’s Family Left Me Stranded on the Highway — So I Sold Their House Without a Second Thought… ch2

Everything began about six months ago, when my son Ethan called me sobbing. “Mom, we’re in trouble,” he choked out,…

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract… CH2

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract……

End of content

No more pages to load