She Was Just the Cook — Until She Refused a General’s Direct Order

Part 1

The first time Elena Ruiz stepped onto the cracked asphalt outside the mess hall at Fort Bragg, the smell of bleach and bacon hit her like a wall. It was barely dawn, the sky a gray-blue bruise, and the exhaust from a convoy of idling trucks rolled low along the ground. Somewhere downrange, a cadence call rose and fell, boots striking in unison like a giant mechanical heart.

She stood there a moment, duffel at her feet, fingers curled tight around the strap. This wasn’t how she’d imagined following in her father’s footsteps.

Her father’s uniform had always looked too big for him, the fabric hanging off his narrow frame, his medic’s patch fraying at the edges. He used to say the Army was the only place where a quiet man could still make a loud difference. Not by shouting orders. By keeping people alive.

He had told her stories at the kitchen table, his voice low, the ceiling fan ticking above them. Stories about blood and sand and the metallic taste of fear. But he always came back to the same point.

“You don’t stand between bullets and a man’s heart, mija,” he’d say, placing a calloused palm over his chest. “You stand between his heart and the moment it gives up. Sometimes that’s a bandage. Sometimes it’s a hand. Sometimes it’s a bowl of soup.”

He died of a heart attack when she was nineteen, sitting in that same kitchen chair. No bullets. No sand. Just a silent betrayal inside his chest.

Maybe that was why, a year later, Elena signed up.

Not for glory. Not for the stories. She signed the papers because she didn’t know what else to do with the ache that had settled in her ribs, and because the recruiter had said they needed cooks in the 82nd.

“It’s not glamorous,” he’d warned her, shoving a stack of brochures into a folder. “But you’ll never forget what it means. People remember the ones who kept them going.”

She learned quickly that at Fort Bragg, nobody romanticized the mess hall. It was a place of clatter and steam, of shouted orders and overflowing trays. The ovens were temperamental, the dishwashers ancient, the walk-in refrigerators prone to groaning like they were haunted. The air was a constant mix of grease, coffee, and the sour tang of sweat.

Her first week, she burned an entire sheet of biscuits because she’d stopped to watch a platoon jog past the window, lips moving silently to their cadence.

“Hey, Ruiz!” a sergeant had snapped, waving a smoking tray. “You’re not here to spectate the infantry. We don’t feed soldiers, we fuel missions. You wanna watch the show, you sign up for it. You’re in the engine room. Understand?”

She did. And she liked it.

She liked the rhythm of the day: the pre-dawn rush of breakfast, the midmorning lull when she could lean against the counter and sip burnt coffee while the dishwashers hissed. She liked the ritual of preparing lunch and dinner, the chopping and stirring and seasoning, the way a line of tired, hollow-eyed soldiers could walk in and walk out straighter, louder, more themselves.

She learned names without trying—Harper, who always asked for extra eggs; Tran, who swore the Army coffee was what would kill him, not the enemy; Dawson, who joked too much and laughed too loud and always lingered an extra second to tell her thank you.

Sometimes, when the line thinned, they talked.

“You ever think about going combat, Ruiz?” Dawson had asked once, leaning his tray on the sneeze guard.

She shrugged. “My dad was a medic. He said saving lives was more important than taking them. Somebody’s gotta make sure you don’t pass out mid-mission ‘cause you skipped breakfast.”

He grinned. “I like the way you think, cook.”

In the evenings, when the lights were turned down and the last of the dishes rattled through the machine, she’d stand alone in the mess hall and listen to the hum of the base through the walls. Helicopters in the distance. A burst of laughter from a barracks window. A void of silence that said someone, somewhere, was packing for deployment.

Then, one afternoon, her name was called.

They were gathering a unit for Kandahar.

Her section chief broke the news over a crate of potatoes.

“Ruiz, you’re on the list. Congratulations. Or condolences. Depends on how you look at it.”

Her stomach lurched. “Kandahar. That’s… Afghanistan.”

“Good to know geography wasn’t lost on you,” he said dryly. “They need bodies. They need cooks. You’ll keep people fed, same as here. Just a different set of noises outside the walls.”

She thought of her father’s stories. Of sandstorms and helicopters and the way he’d go quiet when he said the word “deployment,” as if it were something you didn’t say too loud in case it heard you and came back.

That night, she sat on her bunk with her phone in her hands and no one to call. Her mother had left when she was ten. She had cousins, but they were distant, orbiting their own lives. The only thing she had was a faded photo of her father in Iraq, dust on his uniform, a tired half-smile on his face.

She propped the photo against her lamp.

“Well, Papa,” she murmured. “Looks like I’m going to see some of what you saw.”

The deployment train-up blurred into a series of shots, briefings, and packing lists. She learned about the burn pits, about the dangers of contaminated water, about how even the smallest slip with food could mean sickness that sidelined an entire squad.

“Out there,” the preventive medicine NCO told them, stabbing a finger at a slide of bacteria magnified a thousand times, “one bad batch can do more damage than a firefight. You think you’re ‘just cooks’? You’re a choke point. You mess up, they pay the price.”

The words dug in deep. She wrote them down in a small notebook she kept in her pocket, under a simple title: Things That Can’t Be Wrong.

Finally, they boarded a plane loaded with rucks and rifles and nervous jokes. The air smelled like jet fuel and fear. Elena sat between Dawson and Tran, hands folded in her lap.

“You ever flown this far?” Dawson asked.

She shook her head. “First time.”

He grinned. “You’ll love it. The in-flight meal is terrible, but I hear the scenery’s unforgettable.”

She forced a smile, but her fingers kept straying to the small card in her pocket—a laminated reference for food safety temps, scribbled over with her own notes. A different kind of weapon.

Five refueling stops and a blur of time zones later, the ramp dropped, and a wave of heat and dust slammed into her.

Kandahar Airfield.

The sky was too bright. The ground, all shades of brown and gray. The air thrummed with the constant roar of engines, the chop of rotors, and the occasional distant boom that nobody flinched at but nobody ignored.

As they shuffled down the ramp, a soldier in dusty fatigues yelled over the noise.

“Welcome to KAF! Don’t touch anything that buzzes, glows, or moves fast. If it smells weird, salute it or step away. That includes the food.”

Dawson muttered, “Comforting.”

Elena tightened her grip on her bag. Somewhere in that chaos was a mess hall, with ovens and freezers and stacks of trays. A place she understood.

Inside the wire, nothing was quite like Fort Bragg. The mess hall here was a cavernous tent reinforced with plywood, the floors a mix of worn linoleum and ground-in sand. There were flags tacked to the rafters, handwritten signs over the serving line, and a constant film of dust no matter how often they wiped.

She met the local staff—contractors, other Army cooks, a few civilians who’d been here longer than anyone could remember.

“You’re Ruiz?” a broad-shouldered staff sergeant asked, looking up from a clipboard. “You’ve got a good record at Bragg. Don’t screw it up here. Things are tight. Supplies come when they come. We make do. But we do it by the book. No shortcuts when soldiers’ guts are on the line.”

“Yes, Sergeant.”

She walked the length of the kitchen, familiarizing herself with the layout. Walk-in coolers lined one wall, their seals caked with dust. Industrial burners hissed under blackened pots. A long prep table held mountains of vegetables, some bruised, some not. A radio crackled in the corner, tuned low to a country station that cut in and out.

She felt the rhythm trying to form, the way it had at Fort Bragg. Breakfast. Lunch. Dinner. Fuel the missions. Keep the engine running.

On the third day in Kandahar, she wrote a new line in her notebook.

You can’t control the war outside the walls. But you can control what goes on a plate.

She underlined it twice.

Part 2

The days melted together, a pattern stitched over sand and steel.

Elena woke before sunrise, sometimes to the call to prayer echoing faintly from beyond the wire, sometimes to the throbbing roar of helicopters coming in heavy with cargo or casualties. She’d swing her legs off the cot, tug on her boots, and walk the gravel path to the mess hall under a sky littered with more stars than she’d ever seen.

Inside, the ovens were already roaring. Coffee pots burbled like cauldrons. Someone would have the radio tuned to an American station so distant it sounded underwater. They moved around each other in practiced silence, a dance of spatulas and ladles.

She found a strange peace in the routine. It distracted from the other sounds—the distant thuds like a giant knocking at the door, the sudden sirens, the momentary lulls where everyone seemed to hold their breath at once.

She didn’t ask about the sirens. She didn’t have to.

Sometimes, a squad would come in late, uniforms streaked with dust, faces drawn and older than they’d been a week before. They moved slower, talked quieter. They ate as if they weren’t sure they remembered how.

She never asked them where they’d been. She just gave them extra helpings, slid an extra cookie or two onto their trays, and said, “Eat. You need it.”

One afternoon, as the heat pressed in like a physical weight, a new face appeared in the serving line. His rank was unmistakable: silver bar, with a red cross patch on his shoulder.

“Lieutenant Hayes,” he introduced himself when the line thinned and he stepped around the counter, offering a hand. “Medical platoon.”

“Elena Ruiz,” she said, shaking his hand. “The one who makes sure your guys don’t pass out from hunger during drills.”

He smiled faintly. “I’ve already treated two heat exhaustion cases this week. So you and I? We’re on the same side.”

“Always good to have medics on my side.”

Over the next weeks, their paths kept crossing. Late-night coffee in the corner of the mess hall. Quick conversations over the clatter of trays.

He talked about triage tents, about IV bags hanging from makeshift stands, about trying to keep infections at bay in conditions that hated cleanliness.

“It’s not the explosions that scare me most,” he admitted once, staring into his mug. “It’s the invisible stuff. Bacteria. Viruses. The things nobody sees until half a platoon is doubled over.”

“Food poisoning,” she said.

“Yeah.” He glanced up. “You’d be surprised how many missions go sideways because a squad got careless at the chow line, or some contractor cut a corner. Cooks like you? You’re my first line of defense.”

The words settled over her like a weight and a gift all at once.

That night, she added to her notebook.

Hayes says we’re his first line of defense. The medic and the cook. Not glamorous. But necessary.

The mess hall in Kandahar served three thousand meals a day when the tempo was high. Supplies came in fits and starts—pallets of canned goods, frozen meat, sacks of rice. They learned to improvise, to stretch what they had without stretching safety.

One evening, as they were inventorying a shipment, Elena noticed a pallet of beef that had arrived later than scheduled. The boxes were beaded with condensation that didn’t look right.

“Thermometer,” she called, reaching for the probe hanging on a hook.

She checked the surface, then asked for a box to be opened. The cold air that should have rolled out was weak, barely cooler than the kitchen itself. She pushed the probe into the thickest part of the meat.

Too warm.

Her section chief glanced at the reading and scratched his jaw. “Reefer truck broke down on the way in, probably. Happens.”

“We can’t serve this,” she said.

He hesitated. “We send this back, who knows when the next shipment comes. We’re already short on protein this week. People are going to notice.”

“People are going to notice more if they spend the night puking their guts out instead of going on patrol.”

He studied her, then nodded once. “You flag it. We’ll see what we can substitute.”

It wasn’t the first time she’d made a call like that. It wouldn’t be the last. Each time, it knotted her stomach, because here, everything was a trade: safety versus scarcity, policy versus reality. But the numbers in her notebook—safe temps, times, risks—didn’t care about supply issues. Biology didn’t care about logistics.

In Kandahar, the hierarchy was as visible as the rank on a chest. From privates to sergeants, captains to colonels, the chain of command was everything. Orders came down like gravity. You followed them because that was how the machine worked.

And yet, her father’s voice kept threading through the days.

“Obedience is a tool,” he’d said once. “Not a religion. You follow orders that keep people alive. You question the ones that don’t. Carefully. Respectfully. But you don’t sell your conscience because someone has more stripes.”

She had believed that was philosophy. Here, it felt like a dangerous luxury.

She heard stories. Everyone did.

A corporal who’d questioned a convoy route and gotten reassigned to a desk until the rotation ended. A sergeant who’d refused to sign off on faulty equipment and found himself suddenly unpopular with his chain of command.

“You keep your head down,” one of the older cooks advised her. “Do your job. Let officers fight their battles. You start playing hero, the system chews you up.”

She nodded, but she kept checking temperatures, kept sending back boxes that smelled wrong, kept scribbling notes in the margins of her notebook.

One morning, weeks into their deployment, the base woke to a buzzing tension.

Rumors moved faster than vehicles. A four-star was coming through.

“General’s doing a tour,” the staff sergeant said, wiping his hands on a towel. “Inspections. Morale visits. Dog and pony show, but a high-stakes one. So today, we do everything by the manual. Smiles, yes-sirs, and no surprises. Got it?”

Elena had never seen a four-star general in person. She’d seen photos—stern faces, rows of ribbons. Men whose decisions rippled across continents.

This one had a name she’d heard in passing briefs: General Daniel Morgan.

“Hard-core,” someone muttered. “Old school. Zero tolerance for sloppy discipline.”

“Lucky us,” someone else said.

Elena moved faster than usual that morning, checking and re-checking the line. Scrambled eggs properly held. Bacon crisp but not charred. Milk and juice in the chillers, temp logs up to date. She pulled trash bags, wiped edges, straightened signs.

Around mid-morning, as the breakfast rush tapered, a supply truck backed up to the loading bay. The driver jumped down, a bandana over his mouth, clipboard in hand.

“Got your meat order,” he called.

She frowned. “That’s tonight’s delivery? It was supposed to be here at oh-five-hundred.”

“Convoy got delayed. You want it or not?”

She felt the prickle of unease. Delayed meant time. Time meant potential temperature abuse.

“Unload it,” she said. “We’ll check it.”

They stacked the boxes on palettes in the corner. The air outside was already hot; sand stuck to sweat, to cardboard, to everything. She took her thermometer and stepped forward.

The first box she opened was cool. The second, suspiciously less so. By the time she probed the third and saw the reading, her throat had gone dry.

“Ruiz?” the staff sergeant asked.

“These aren’t cold enough,” she said. “Looks like the reefer unit cut out at some point. How long were you delayed?” she called to the driver.

He shrugged. “Hour, maybe two. Hard to say. We got stopped at the checkpoint for a while.”

“Did the truck stay running?”

He hesitated. “Mostly.”

Mostly.

Her pen scratched over the sheet, logging the temp. It was above the safe range. Not by a small margin.

Her section chief cursed quietly. “We’ve got three hundred pounds of beef here. That’s the main entrée for tonight. If we toss it, we’re looking at canned beans and rice for everybody. Not exactly morale food.”

“We can’t serve it,” Elena said. Her voice was steady, but she felt the pressure building, like heat behind glass. “Regulations say—”

He cut her off with a raised hand. “I know what the regs say. I’m just telling you what we’re up against.”

A shadow fell over them.

“What exactly are we up against, Sergeant?”

The voice was clipped, calm, and carried an authority that made everyone straighten instinctively.

Elena turned.

General Daniel Morgan stood there, flanked by a pair of aides who looked carved from the same stone. He wore his rank lightly, as if it were just another piece of gear, but there was no mistaking the way people around him shifted, shoulders squaring, spines snapping a little straighter.

The staff sergeant swallowed. “Sir. We, uh, just received tonight’s meat shipment. There appears to be an issue with the refrigeration.”

Morgan’s gaze flicked to the stacked boxes, then to Elena, whose thermometer still protruded from the opened meat.

“You’re the one holding the instrument,” he said. “Report.”

She forced her voice not to tremble. “Sir, the internal temperature of several boxes is above the safe threshold for perishable meats. They were delayed in transit, and it appears the refrigeration unit may have failed. Regulations require we consider this shipment unsafe for consumption.”

He studied her, eyes an unreadable gray.

“What’s your name, Corporal?”

“Ruiz, sir. Corporal Elena Ruiz.”

“How long have you been a cook?”

“Three years, sir. One at Bragg, two here, including deployment.”

“Mm.” He stepped closer to the box, peered at the thermometer, then at the sweat gleaming on the plastic-wrapped beef. “What’s on the menu tonight?”

“Beef stew for the main line, sir,” the staff sergeant answered. “We planned around this shipment.”

“So if you throw this out, what do you serve instead?”

“Canned goods, sir. We can improvise, but it’ll be… limited.”

Morgan’s jaw tightened almost imperceptibly. “The unit rotates out tomorrow for a major operation. They need calories. Real food. Not ration-grade improvisation.” He turned back to Elena. “You said the meat was above safe temps. By how much?”

She told him. He nodded slowly.

“And your recommendation, Corporal Ruiz?”

She knew what he wanted to hear. She could see it in the way the staff sergeant’s fingers twitched on the clipboard, in the way the driver shifted his weight.

“Regulations require we discard this shipment, sir,” she said carefully. “Serving it would pose a significant risk of foodborne illness. With respect, we can’t guarantee it’s safe.”

He held her gaze for a moment that felt too long.

“Then here’s my order,” he said. “Use it anyway. If there are any consequences, I’ll take responsibility. That’s what command is for.”

The staff sergeant exhaled, shoulders dropping a fraction. The driver relaxed.

Elena didn’t move.

Responsibility. The word echoed, hollow.

She imagined three hundred soldiers bent over toilets instead of maps. She imagined Hayes, eyes shadowed, hanging IV bags in a tent that smelled like bleach and sickness. She imagined patrols going out short-handed because half their strength was curled on cots, shivering and clammy.

“Sir,” she heard herself say, “respectfully, that doesn’t change the biology. The risk is the same, regardless of who signs off.”

Several nearby soldiers went very still.

Morgan’s eyes narrowed a fraction. “Are you refusing a direct order, Corporal?”

The mess hall seemed to disappear. The roar of the base receded. All she could hear was her pulse, loud in her ears. She thought of her father, of his stories, of the way his hand had felt over hers on the kitchen table.

You don’t sell your conscience because someone has more stripes.

She swallowed.

“No, sir,” she said. Then, after a heartbeat that felt like a drop off a cliff: “I’m refusing an unsafe one.”

The words hung in the hot, dusty air like a flare.

Part 3

Silence rolled through the loading bay, thick and heavy.

Somewhere behind them, a tray clanged to the floor. No one bent to pick it up.

General Morgan’s expression didn’t change much, but the air around him seemed to harden.

“Corporal Ruiz,” he said quietly, “let me be very clear. I have given you a lawful order. You will use this shipment to feed the unit tonight. Any risk will be assumed by me as the commanding general. That is the chain of command. That is how this works.”

Her mouth had gone dry. Her palms were slick. But beneath the fear was something hard and immovable.

“Sir,” she said, “my duty as a food service specialist is to protect the health of the soldiers we feed. Regulations, training, and medical guidance are explicit. This meat is unsafe. Serving it would knowingly endanger personnel. I cannot, in good conscience, comply.”

A muscle ticked in his jaw. One of his aides shifted, lips parting as if to intervene, but Morgan lifted a hand asking for nothing more than patience.

“Sergeant,” he said, eyes still on Elena, “what’s the penalty for refusing a direct order in a combat zone?”

The staff sergeant’s voice was barely a whisper. “Article 90, sir. Could be court-martial. Imprisonment. Dishonorable discharge.”

Morgan nodded once, then stepped closer until he was only a foot away. Elena smelled dust and starch and something faintly metallic.

“You understand what you are risking,” he said. It wasn’t a question.

She forced herself not to look away. “Yes, sir.”

“You are prepared to face charges. To lose your rank. Your career.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And for what? A truck that was delayed. Meat that is a few degrees outside some textbook range.” His voice sharpened. “Are you telling me, Corporal, that you know better than your commanding general what this unit needs on the eve of a critical operation?”

Her throat tightened. “I’m telling you, sir, that I know what unsafe food does to a human body. That I’ve seen the numbers on foodborne illness in deployed environments. That Lieutenant Hayes, our medic, briefed us—”

“Hayes is not here,” Morgan cut in. “I am.”

She hesitated—only a fraction, but enough.

He pounced.

“You don’t have the luxury of perfection in war,” he said. “You have the reality of tradeoffs. Would you rather they go out hungry and weak? Do you think the enemy will care that their rations were ‘by the book’ when they’re too exhausted to move with speed?”

The question hit like a slap. For a moment, doubt flared.

Then she remembered the training slides. The warning Hayes had given her. One bad batch can do more damage than a firefight.

“Sir,” she managed, “there are alternatives. We can increase portions of the canned goods, add more starch, adjust the menu. It won’t be ideal, but it will be safe. Weak from hunger is one thing. Hospitalized from contamination is another. I’m willing to take responsibility for the menu. I am not willing to take responsibility for an avoidable outbreak.”

He stared at her, and she realized suddenly that it wasn’t anger in his eyes. It was something more complicated. Calculation. Curiosity. Maybe even a flicker of respect that he was shoving down hard.

“Last chance, Corporal,” he said softly. “Comply with my order, or confirm your refusal.”

Her heart hammered. Each beat seemed to drive a spike deeper into the moment, pinning it in place.

She saw two paths.

On one, she stepped aside, swallowed her training, and did what he asked. The headlines, if there were any, would never mention her name. The risk would become just another data point in a system that measured everything but conscience.

On the other path, she plunged into freefall.

Her father’s voice, sharp and clear as if he were beside her, cut through the panic.

Sometimes, the bravest thing you can say is no.

She exhaled.

“I confirm my refusal, sir.”

The aide to Morgan’s left made a quiet sound, like someone stifling a cough. The staff sergeant closed his eyes for a second, then squared his shoulders.

“Very well,” Morgan said.

He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t slam a fist. In some ways, his calm was worse.

“Sergeant, remove Corporal Ruiz from the kitchen. She is relieved of duty, effective immediately. Place her under supervision pending formal charges for insubordination and refusal to obey a lawful order.”

The staff sergeant’s face tightened, but his reply was automatic. “Yes, sir.”

He turned to Elena. For the first time since the confrontation began, there was something almost human in his eyes.

“You have made your choice, Corporal,” he said. “We’ll see what it yields.”

Two MPs appeared with a speed that suggested they’d been hovering nearby, waiting. They weren’t rough, but their presence at her elbows felt like iron.

As they guided her away, she caught glimpses of faces in the kitchen. An older cook with his jaw clenched, staring at a point over her head. A young private, eyes wide, frozen between admiration and horror. The driver gnawing his lip, suddenly fascinated by his boots.

Outside, the sun hit her full in the face. The base was humming, oblivious. A helicopter lifted off in a storm of dust. A convoy rumbled by, soldiers perched in the turrets squinting against the glare.

“You didn’t have to do that,” one MP muttered under his breath as they walked. “Could’ve just logged a complaint later. Chain of command exists for a reason.”

She swallowed. “If someone got sick, later wouldn’t matter.”

He shook his head, but there was a flicker of something in his eyes she couldn’t read.

They didn’t put her in a cell. This wasn’t a movie. They escorted her to a small office near the admin building, sat her in a chair, and closed the door. The hum of an air conditioner rattled overhead. A half-empty coffee mug sat on the desk, abandoned in a ring of its own making.

There was nothing to do but wait.

Her thoughts swarmed. She tried to steady them by focusing on the details—the way the sunlight slanted through the blinds, the faint stain on the carpet, the minute ticking of a clock above the door.

You idiot, one voice whispered. You just threw away everything. For what? For some numbers on a thermometer?

Another voice answered, quieter but steadier. For them. For the ones who trust you to get it right.

Hours seemed to drip by. An officer came in at one point, asked her to recount the events. She did, carefully, aware that every word might end up in a report. He jotted notes, expression unreadable, then left.

At some point, a private slid in with a plastic tray—sandwich, chips, a bottle of water. He didn’t quite meet her eyes.

“I heard what you did, ma’am,” he mumbled.

“I’m not a ma’am,” she said automatically. “Just a corporal.”

He hesitated. “Still. Took guts.”

Before she could answer, he was gone.

Twilight was bleeding into night when the door opened again and Lieutenant Hayes stepped in, dust on his boots, fatigue lines carved deep.

“Elena,” he said, closing the door behind him. “I had to pull a few strings just to get five minutes.”

She looked up, throat tightening. “How bad is it?”

He sat across from her, fingers drumming on his knee.

“Bad enough,” he said. “Rumor mill is on fire. Some say you mouthed off to the general. Some say you threw a tray at him. My favorite is that you threatened to poison his coffee.”

Despite everything, she barked out a laugh.

“Relax,” he said, lips twitching. “I corrected the record where I could.”

The laughter died as quickly as it came. “They’re going to crucify me, aren’t they?”

He didn’t answer immediately.

“You refused a direct order,” he said finally. “In a forward operating base. From a four-star. That’s not something they overlook.”

She swallowed hard.

“But,” he added, leaning forward, “you were right on the facts. I saw the temp logs before they took you out. That shipment was compromised. I’d have backed you on that call.”

“Will that matter?” she whispered.

“It might,” he said. “Depends on what happens next.”

“What happens next?”

He hesitated, as if weighing how much to tell her.

“Another unit got a shipment from the same supplier,” he said. “Different base, few hours north. They didn’t have anyone like you checking temps. Or if they did, nobody listened.”

Her stomach knotted.

“What happened?”

His eyes darkened. “We’re still getting reports. But so far? Over twenty soldiers with acute gastrointestinal symptoms. Vomiting. Diarrhea. Dehydration. A few severe cases. They’ve traced it back to the meat.”

The room seemed to tilt. She gripped the edge of the chair.

“The same batch?” she managed.

“Same supplier. Same lot numbers. Same reefer line. If what we’re hearing is accurate…” He let the implication hang.

If she’d complied. If.

She swallowed hard. “Have they told the general?”

“Oh, they will,” Hayes said. “Central command is already buzzing. Food safety, logistics, preventive med—they’re all over it. Nobody wants a preventable non-combat incident on the stats right now.”

Her pulse thundered. “So maybe…”

“Maybe,” he said, holding up a hand. “Don’t get ahead of yourself. The wheels turn slow, even in a crisis. But one thing’s sure: your decision just became more complicated for them to punish.”

He leaned back, studying her.

“You scared?” he asked.

She let out a breath that was almost a sob. “Terrified.”

“Good,” he said. “Means you understand the stakes. Courage isn’t the absence of fear, Elena. It’s refusing to let fear pick your choices.”

He stood. “I have to go. I’ve got a tent full of sick soldiers and not enough fluids. But I wanted you to know. Whatever happens with the brass? In my book, you did exactly what you were supposed to.”

“Thanks,” she whispered.

He paused at the door. “One more thing. If they try to tell you that you endangered readiness by tossing that meat, remind them of the twenty-plus guys currently stapled to cots. Ask them how ready those missions are.”

And then he was gone.

Night settled over Kandahar like a heavy blanket. Somewhere outside, a helicopter thudded low. Voices rose and fell.

Alone in the office, Elena rested her head in her hands.

She had no control over the investigation that had just begun. No control over what general officers whispered to each other behind closed doors. All she had was the decision she’d made, the thermometer reading burned into her memory, and the knowledge of what had happened up north.

She thought of her father again, of the stories he’d never finished. Had he ever refused an order? Had he ever sat in a room like this, wondering if he’d set his own life on fire for the sake of someone else’s?

“If I did wrong,” she whispered into the empty room, “let it be the kind of wrong I can live with.”

Outside, the base kept humming.

Inside, the clock ticked toward whatever came next.

Part 4

The investigation came not as a single thunderclap, but as a series of controlled detonations.

First, a captain from JAG appeared with a notepad and a voice like sandpaper. He asked Elena to recount the events again, this time with emphasis on exact wording.

“When the general said he’d take responsibility, did you interpret that as a mitigation of risk?”

“Risk doesn’t care about paperwork, sir,” she answered. “Only about conditions.”

He scribbled, mouth twitching, but he didn’t argue.

Next came a major from preventive medicine, eyes sharp behind thin glasses. He carried copies of temp logs, shipping records, and a stack of regulation printouts an inch thick.

“You logged these readings personally?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“You were trained on proper thermometer calibration and insertion?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You are aware that your reading placed the meat well within the documented hazard zone for pathogen growth?”

“Yes, sir.”

He nodded, almost satisfied. “Good. That part, at least, will be simple to prove.”

“Simple to prove?” she echoed.

“That the meat was unsafe,” he said. “Everything else is politics.”

He left her with that and a sinking feeling.

They moved her from the office to a makeshift billet near the admin area—a small, partitioned space in a tent with a cot, a footlocker, and a curtain for privacy. She was technically under supervision, but not confinement. An MP checked in every few hours. She wasn’t allowed near the mess hall.

On her second day of exile, Dawson appeared during visiting hours, smelling faintly of engine grease and dust.

“Damn, Ruiz,” he said, dropping onto the cot next to her. “You really know how to make a splash.”

She tried to smile. “I always wanted to be known for something. I was thinking maybe my chili, not career suicide.”

He snorted. “Half the base is talking about you. Some say you’re crazy. Others think you’re some kind of hero.”

“And you?”

He scratched his jaw. “I think you did what you believed was right. And I think that scares people. Because most of us? We tell ourselves we’d do the same, but we’re not sure.”

She looked down at her hands. “I wasn’t sure either. Not until I heard myself say it.”

“Well,” he said, clapping her on the shoulder, “if they kick you out, you can open a restaurant. Call it ‘The Refusal.’ I’ll be your first regular.”

“I’ll serve you lukewarm meat and see how long you last.”

He laughed, and for a moment the tent felt less like a holding pen and more like a corner table somewhere far from sand and sirens.

Visits became her lifeline. Tran stopped by, leaving a contraband chocolate bar on her pillow with a whispered, “For when the MREs break you.” A young private from the dishwashing crew came in to tell her that the staff sergeant had quietly adopted her food safety log format.

“Guess you made an impression,” the private said.

She heard whispers, too, carried in by those who came and went.

“General Morgan’s been… quiet,” Dawson reported one day. “No yelling. No making an example of anyone. He’s been in meetings, though. Lots of them.”

“Good quiet or bad quiet?” she asked.

“With officers?” Dawson shrugged. “Who knows.”

Meanwhile, the situation at the other base solidified into grim fact.

An email briefing was inadvertently left open on a screen during one of her interviews; she caught a glimpse before they clicked it away. Phrases floated in her mind afterward: “cluster of foodborne illness,” “common exposure,” “operational readiness compromised,” “suspected contaminated beef.”

Hayes confirmed it during another rushed visit, dark circles under his eyes.

“I’ve been consulting over the wire,” he said. “They’re overloaded. Lost a couple of missions this week because too many guys were down. It’s not life-or-death for most of them, but it’s bad. And it was preventable.”

He met her gaze. “Just like you said.”

“Does central command know it’s the same supplier?” she asked.

“Oh, they know,” he said. “Company’s already on a temporary suspension pending investigation. Logistics is scrambling. And word is, someone up the chain connected the dots back to your little standoff.”

Her stomach clenched. “Is that good or bad?”

“Depends on who’s telling the story,” he said. “To some, you’re the cook who disobeyed a general. To others, you’re the one who kept this base from joining that mess.”

“And what about General Morgan?” she asked quietly.

Hayes’s face shifted minutely. “He’s in a tight spot. On paper, he gave a lawful order. You refused. But now that order looks… unwise, in hindsight. Which makes punishing you messy. Nobody up top likes messy.”

“So they’ll find some middle ground,” she guessed. “Slap me on the wrist quietly, move me somewhere nobody sees.”

“Maybe,” he said. “Or maybe something else. I’ve seen careers die over less. I’ve also seen them twist themselves into knots to avoid admitting a lower-ranking soldier was right.”

He stood. “Whatever comes, remember this: you didn’t gamble with their lives. You refused to.”

Days stretched. The world narrowed to the path between her tent and the admin building, the curtained-off interview rooms, the creased edges of the cot where she sat and counted breaths.

In her notebook—returned to her after someone had leafed through it for anything incriminating—she wrote not about temperatures, but about fear.

Fear is like heat. You can’t see it, but you feel it. It grows in certain conditions. But courage is the decision not to let it boil you alive.

One evening, just as the sky outside was turning the color of old bruises, an MP stuck his head through the curtain.

“Corporal Ruiz,” he said. “Command wants to see you in the main briefing room.”

Her pulse spiked. “Now?”

“Now.”

She followed him through the maze of tents and containers, gravel crunching under their boots. They passed soldiers heading to and from shifts, a couple of contractors dragging hoses, a chaplain lighting a cigarette in the shadow of a blast wall. Life went on, steady and indifferent.

The main briefing room was a prefab building with a blast-resistant shell and a dozen rows of folding chairs. She’d been in it before for briefings, sitting in the middle, anonymous. Now, she stepped in and stopped.

The room was full.

Officers in pressed uniforms. NCOs with crossed arms and set jaws. A few civilians in polo shirts with contractor logos. At the front, a podium, a projection screen, and an American flag standing stiff in its base.

And in the center of the front row, General Daniel Morgan.

He wore the same uniform, but something in his posture was different. Less coiled. More… resolved.

As she entered, conversations dipped. Heads turned. A ripple moved through the room.

The MP guided her to a chair at the side, near the front, and retreated to the wall.

For a moment, she felt like she was underwater, sound muffled, vision too sharp. Her gaze snagged on Hayes, standing near the back, his arms folded. He gave her a brief nod.

At exactly nineteen hundred, Morgan stood and moved to the podium.

“Take your seats,” he said.

The murmur died.

He looked out over the crowd. When his gaze slid over her, it paused for a heartbeat, then moved on.

“We are gathered here today,” he began, “because this base recently skirted a disaster.”

The word landed with weight.

“Two days ago,” he continued, “another forward operating base in our theater experienced a significant foodborne illness incident. Over twenty soldiers were rendered temporarily combat-ineffective. Several required intensive medical support. Missions were canceled. Operational readiness was degraded. All because of a failure in something as mundane as refrigeration.”

He let that sink in. No one shifted. No one coughed.

“The meat in question,” he went on, “came from a batch supplied by the same contractor who delivered to this base. Same lot, same transport chain, same potential for temperature abuse.”

A faint stir moved through the room. People glanced at one another.

He lifted a sheet of paper.

“The logs and investigations confirm that our shipment was also compromised. That the temperatures recorded placed it firmly in the hazard zone. That, had it been served, we would likely be having this same conversation about our own sick soldiers.”

He set the paper down.

“We are not having that conversation,” he said, “because one person refused to let it happen.”

His words, and the way he said “refused,” sent a chill down her spine.

He nodded toward the side.

“Corporal Elena Ruiz, please stand.”

Her legs felt like they belonged to someone else. Still, she pushed herself up, every eye in the room turning toward her.

“This soldier,” Morgan said, “was faced with an impossible choice. On one side, the chain of command. The operational need for a high-calorie meal before a major mission. On the other, the clear evidence that the food on hand was unsafe. She was ordered—by me—to use that food anyway, with my assurance that I would ‘take responsibility.’”

A murmur. Some shocked faces. A few expressions quickly schooled to neutrality.

“She refused,” he said simply.

The word hung there, no longer an accusation but something else.

“At the time,” he continued, eyes on her now, “I saw only defiance. A challenge to authority. An obstacle between my intent and my plans. I reacted accordingly, relieving her of duty and initiating proceedings for insubordination.”

The admission felt surreal. A four-star general, saying this out loud, in front of everyone.

“Since then,” he said, “evidence has come to light that her assessment of the risk was correct. In fact, dangerously understated. The outbreak at the other base confirmed what our logs already suggested—that the shipment posed an unacceptable threat to our soldiers’ health and to mission readiness.”

He stepped away from the podium, moving closer, until he was only a few feet from where she stood.

“What I did not see in that moment,” he said, “was that Corporal Ruiz was not defying her duty. She was fulfilling it. Not as a cog in a machine, but as a steward of her fellow soldiers’ welfare.”

His gaze swept the room.

“Too often, we talk about courage as if it wears only one face—the one charging a hill under fire, the one pulling a wounded comrade from a burning vehicle. That courage is real. It is sacred. But there is another kind, quieter and just as vital: the courage to say no when everyone expects you to say yes. The courage to refuse an order that you know, in your bones, will harm the very people you are sworn to protect.”

He turned back to her.

“Corporal Elena Ruiz,” he said, “I owe you something I do not often give.”

He paused.

“An apology.”

The room was utterly silent. Even the air conditioner seemed to hesitate.

“I was wrong,” he said. “Not only in my judgment of the risk, but in my assumption that obedience is the highest virtue in uniform. It is not. Integrity is. You had it. In that moment, I did not.”

Her throat burned. She swallowed hard, fighting the instinct to look at her boots like a chastised recruit. She forced herself to meet his gaze.

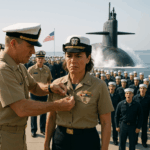

He reached into his pocket and withdrew a small box.

“In light of these events,” he said, “central command has decided to drop all charges against you. Furthermore, they have authorized me to present you with the Army Commendation Medal for exceptionally meritorious service in a combat zone, for decisively acting to prevent a potential mass casualty incident due to foodborne illness.”

He opened the box, revealing the green-and-white ribbon with its bronze medal.

“Step forward, Corporal.”

Her legs carried her to him. She could feel the eyes on her, the weight of the moment pressing in.

He pinned the medal above her heart with practiced hands. For a second, his fingers brushed the fabric where her father’s dog tags rested underneath.

“Leadership isn’t about power,” he said quietly, for her ears and the room’s. “It’s about conscience. You reminded me of that.”

She blinked hard against the sting in her eyes.

“Yes, sir,” she managed.

He stepped back and saluted her.

For a heartbeat, she froze.

Then muscle memory took over. She shot up her hand, returning the salute, her fingers sharp at her brow.

Applause broke out—not tentative, not polite, but full and rolling, like a wave. It startled her more than anything else. She saw Dawson on his feet, whistling. Tran clapping hard enough to redden his palms. Hayes, hands in motion, expression a mix of pride and relief.

For a soldier who’d always worked in the background, the sudden visibility was dizzying. But in the roar of appreciation, there was something else—a collective exhale. It was as if the room had been holding in a question and someone had finally answered it out loud.

When the noise ebbed, Morgan returned to the podium.

“In the aftermath of this incident,” he said, “we are instituting a new policy across all forward operating bases under this command.”

He clicked a remote. A slide appeared on the screen behind him, text stark and simple.

Each soldier, regardless of rank or role, has the duty to refuse any order they reasonably believe is unsafe, unlawful, or grossly negligent regarding the health and welfare of personnel.

“This is not a carte blanche for chaos,” he said. “This is a safeguard. It does not absolve anyone from consequences if their refusal is frivolous or self-serving. But it recognizes that conscience and expertise do not always align neatly with rank. It acknowledges that sometimes, the cook knows more about the food than the general does. And that we would be fools to ignore that.”

He looked at her one more time.

“Sometimes,” he said, voice softer but still carrying, “courage comes wearing an apron, not armor.”

Laughter rustled through the crowd—warm, surprised.

The briefing ended. People surged forward, some to shake her hand, others to clap her shoulder. Words tumbled around her: “Proud of you,” “Hell of a thing you did,” “Remind me never to argue with you about steak.”

Through it all, she felt oddly detached, as if watching it from outside herself. The medal on her chest was solid and light all at once.

When the room finally emptied, Morgan approached her without his entourage.

“Corporal,” he said.

“Sir.”

He studied her for a moment.

“That day,” he said, “when you refused, were you afraid?”

She thought about lying. Instead, she said, “More than I’ve ever been.”

“Good,” he said. “If you hadn’t been, I’d worry you didn’t understand what you were doing.”

He hesitated. “You’ve given me something I needed, Ruiz. A reminder that authority is a responsibility, not a shield. I won’t forget it.”

“Thank you, sir,” she said quietly. “For… saying what you did. You didn’t have to.”

“Oh, I did,” he said. “Maybe not by regulation. But by conscience.”

He offered his hand. She shook it.

Then, without ceremony, he turned and walked away.

She stood alone in the echo of the emptying room, the medal a small weight against her heart, the words “duty to refuse” still glowing on the screen behind her.

She had been ready to lose everything. Instead, something had shifted in the world above her pay grade.

It was not victory. Not exactly. War still raged. People would still cut corners. Not every general would listen. Not every refusal would end in applause.

But somewhere, on some future day, a private or a sergeant or another cook might look at an unsafe order and remember that a corporal once said no, and was heard.

For now, that was enough.

Part 5

Life on the base did not transform overnight into a utopia of ethical clarity.

Two days after the ceremony, a supply clerk tried to pressure a young specialist into signing for a damaged shipment without documenting it. The specialist refused and cited the new policy. Voices were raised; a lieutenant got involved; the shipment was sent back.

“Thanks, Corporal,” the specialist said later, sheepish, as he grabbed his tray. “Guess your drama helped.”

She shrugged, ladling stew. “Just doing my job. So are you.”

The mess hall’s rhythm resumed, but something in the air had changed. People looked at her differently now—not just as the cook who knew their preferences, but as the cook who had stared down a general. Some of them seemed to regard her with awe. Others with wary curiosity, as if proximity might get them caught in collateral defiance.

The older cooks, though, treated her much the same.

“You still have to scrub the pans,” the staff sergeant reminded her with a smirk. “Medal or not.”

“Yes, Sergeant,” she said, grinning, rolling up her sleeves.

Yet, late at night, when the rush was over and the kitchen quieted, she would find herself tracing the outline of the medal through her uniform, feeling its shape as if to confirm it hadn’t been a hallucination.

One evening, as she stood alone by the industrial sink, hands plunged in soapy water, Hayes slipped in through the side door.

“Thought I’d find you here,” he said, leaning against the counter.

“Where else am I going to go?” she replied. “I’ve been restored to my natural habitat.”

He smiled, then sobered.

“You know they’re talking about your case at med conferences already?” he said. “Food safety, ethics, command climate. Your name is going to end up in some PowerPoint somewhere as a bullet point.”

“The dream,” she said dryly. “To be immortalized in PowerPoint.”

“Don’t underestimate it,” he said. “Policy shifts start with stories. And stories stick better when they have faces.”

“Is that supposed to make me feel better?” she asked.

“No,” he said. “It’s supposed to remind you that what you did doesn’t end here. Especially for me.”

He tapped his chest, where his medic’s patch caught a glint of fluorescent light.

“I’ve lost patients to infections that never would’ve happened if someone, somewhere, had said, ‘This isn’t safe.’ You made my job easier. Maybe you saved me from having to look some kid in the eye and tell him he was missing a mission because his dinner betrayed him.”

“Anytime I can prevent betrayal by dinner,” she said, “I consider that a win.”

He laughed softly, then his expression turned thoughtful.

“What are you going to do after this deployment?” he asked.

She blinked. “After?”

“Yeah. You staying in? Getting out? Starting a chain of conscience-driven restaurants?”

She shrugged, staring at the foam swirling in the sink.

“I don’t know,” she admitted. “I joined for my father. Then I stayed because… I was good at it. Because it mattered, even if nobody saw. Now…” She shook her head. “Now everyone sees this one thing I did, and I don’t know if that means I’m supposed to keep going or bow out on a high note.”

“Do you still care?” he asked. “About feeding them. About doing it right.”

“Yes,” she said, without hesitation.

“Then that’s your compass,” he said simply. “Medals tarnish. Policies change. But if you still care, that’s worth something.”

She looked at him. “What about you? Going to be a lifer?”

He snorted. “I said I’d do one tour. Then another. Now I’m on my third ‘just one more.’ I keep telling myself I’ll know when it’s time.”

“And do you?” she asked.

He rubbed the back of his neck. “Not yet. But I’m listening.”

Outside, the base speakers crackled to life with a scratchy rendition of some rock song from twenty years ago. A few soldiers’ voices drifted on the night air, singing along, off-key and wholehearted.

“Whatever you choose,” Hayes said, “don’t let this be the only story you tell yourself about who you are. You were brave that day. But you were already brave before, in a hundred smaller ways nobody pinned a medal on.”

She thought of the early mornings at Fort Bragg. The burned biscuits and the adjustments. The boxes she’d flagged and the quiet arguments she’d won and lost. Of her father, steady and unsung in the back of aid stations.

“I’ll try not to forget that,” she said.

Time in a deployment is measured oddly. Days drag; months disappear. Before she knew it, rotation orders started appearing. Names on lists. Flights scheduled. Cargo packed.

Her unit’s departure was bittersweet. Some were staying on longer. Some were transferring out. There were hugs and jokes and deliberately casual goodbyes.

Dawson slapped her on the shoulder as he hefted his ruck.

“Don’t let them forget what you did,” he said. “And if you open that restaurant, remember: I want free coffee for life.”

“You get one free refill,” she countered. “After that, you pay double for making me listen to your bad jokes for a year.”

“Deal,” he said, grinning.

The last time she saw General Morgan in Kandahar, it was on the tarmac. He stood near a transport plane, nodding to departing troops, his presence a mix of formality and genuine regard.

When she passed, he paused.

“Corporal Ruiz,” he said.

“Sir,” she replied, stopping, her duffel over her shoulder.

“Wherever you go next,” he said, “take that same spine with you. The world beyond these fences could use it.”

“I’ll try, sir,” she said.

He looked like he wanted to say more, then just gave a brief, almost personal smile.

“Safe travels,” he said.

The plane lifted off, leaving Kandahar behind in a haze of brown and gold. As the base shrank below her, Elena pressed her forehead to the small oval window and closed her eyes.

She didn’t know what waited on the other side of the ocean. Only that it would be quieter. That there would be no sirens in the night. No distant booms. No convoys rattling over gravel.

Just… life. Whatever that meant now.

Part 6

Years later, the war existed in Elena’s mind as a collage of sounds and smells.

The drone of generators under a hot sky. The sting of bleach and disinfectant. The thud of boots on gravel. The sharp, clean crack of a thermometer case opening.

Those memories surfaced sometimes when she stood in her diner’s kitchen in North Carolina, the clatter of dishes and the murmur of customers blending into a familiar hum.

The diner had been a dream before it had a name. A way to translate what she’d learned in uniform into something civilian. Something rooted.

She found the building by accident—a squat, brick structure on a corner lot off a state highway, with a faded sign that once advertised “Betty’s Country Kitchen.” The windows were dusty. The parking lot was cracked. The ‘Open’ sign hung askew.

Inside, the vinyl booths were split at the seams, the counter stools loose on their bolts. The back room held an aging grill and a refrigerator with a dented door.

To most, it would have looked like a liability.

To her, it looked like a mess hall without the sand. A place where people would come hungry and leave less burdened.

She used her savings, a small business loan, and more sweat than she thought she had to spare. She scrubbed every surface, replaced appliances, painted walls. She learned about health codes and permits, about payroll and insurance. She hung her Army Commendation Medal in a small, unassuming frame in the office—not in the dining area.

Above the counter, in a spot where every customer could see it while they waited for coffee refills, she hung a simple plaque, the lettering carved by a local woodworker.

Integrity is serving what’s right, not what’s ordered.

People asked about it sometimes.

“What’s that mean?” a trucker asked one morning, hat pushed back, forearms resting on the counter.

She topped off his coffee. “Means if something on the menu isn’t up to standard, I don’t serve it, even if it’s the special of the day.”

He chuckled. “Sounds like common sense to me.”

“Common sense isn’t always common,” she said.

He nodded thoughtfully. “Fair enough.”

Veterans found her place the way they always did—through a network of half-remembered conversations and recommendations with no clear origin.

“You gotta check out this diner off Route 15,” someone would say at a VFW bar. “Run by an Army cook. She makes meatloaf that could raise the dead.”

“Is she the one…” someone else might add, lowering their voice, “who stood up to a general? My cousin told me—”

“Yeah, I heard something like that.”

Some who came knew the story. Some didn’t. She never led with it.

She had regulars. A retired sergeant major who always sat in the same booth and read the paper section by section. A young mechanic from the garage down the street who swore her pancakes were the only thing that made Mondays bearable. A widowed nurse who came every Thursday for the chicken soup and stayed for the conversation.

One rainy afternoon, the bell over the door jingled, and a group of younger veterans stepped in, shaking water off their jackets. Their movements had that familiar mix of awareness and weariness. One of them, a woman in her late twenties with a National Guard shirt, stopped short when she saw the plaque.

“Nice sign,” she said, sliding onto a stool. “You in the service?”

“Was,” Elena said. “Army.”

The woman’s eyes flicked to the modest rack of photos on the wall—snapshots of the diner’s opening day, a picture of Elena in uniform with a mess hall in the background, a Polaroid of a group of soldiers holding trays and grinning.

“What’d you do?” the woman asked.

“Food service,” Elena said. “Cook.”

The woman’s face lit with recognition.

“Wait,” she said slowly. “Like… Corporal Ruiz?”

Elena raised an eyebrow. “Depends on who’s asking.”

“My platoon sergeant used to tell a story,” the woman said, turning to her friends. “About a cook in Kandahar who refused a four-star’s order to serve bad meat. Said it changed the policy in theater. We thought it was one of those legends, like the guy who supposedly punched a colonel.”

One of the men laughed. “Every unit’s got one of those.”

“I always figured it was half-made-up,” the woman continued. “Nice moral, you know? ‘Do the right thing even if the brass tells you otherwise.’ But that name…” She squinted at Elena. “That was you, wasn’t it?”

Elena wiped her hands on her apron. The memories came back in a rush—the heat, the boxes of meat, the steady climb of numbers on the thermometer.

“It was,” she admitted. “Though your sergeant probably told it with more explosions than there actually were.”

The woman’s mouth dropped open.

“No way,” one of her friends said. “You’re like, famous.”

“I’m like, someone who made a very stressful career decision a long time ago,” Elena corrected. “You want coffee?”

They laughed, the tension easing.

As she poured, the woman shook her head in amazement.

“You know,” she said, “they talked about that policy at my basic training. About refusing unsafe or unlawful orders. Your story was the example. They didn’t use your name, but they described the situation. I remember thinking, ‘Whoever that cook was, she had more guts than I do.’”

“Trust me,” Elena said, “my guts were not feeling heroic at the time.”

“But you did it anyway,” the woman said.

“Yeah,” Elena conceded. “I did.”

Later, when the lunch rush ebbed and the younger vets lingered over pie, the bell over the door jingled again.

This time, the man who stepped in wore no uniform, but he carried himself with a bearing she recognized instantly. His hair was thinner, his face lined, but his eyes were the same sharp gray.

For a moment, Elena thought she was hallucinating.

“General,” she said without thinking, then caught herself. “I mean… sir. Or is it ‘mister’ now?”

He smiled, the expression softer than she remembered from Kandahar.

“Daniel is fine,” he said. “We’re both civilians now.”

The younger vets paused mid-bite, eyes widening as they took in the scene.

“What brings you here?” Elena asked, moving instinctively to the coffee pot.

“An old friend in the area told me there was a diner I had to see,” he said. “Said the cook had strong opinions about food safety.”

She poured him a cup and slid it across the counter. “Still do.”

He glanced up at the plaque above the counter, reading the words slowly.

“Serving what’s right, not what’s ordered,” he murmured. “I like that.”

“I had good teachers,” she said.

He took a sip of coffee, then set the mug down, studying her.

“You look… at peace,” he said.

“Some days,” she replied. “Other days the fridge breaks and the dishwasher quits and a server calls in sick and I remember that chaos is universal.”

He chuckled.

“And you?” she asked. “How’s retired life treating you?”

He exhaled. “It’s… different. Fewer briefings. More time to think about the things I did and didn’t do. People you lose in war are one kind of ghost. Decisions are another.”

She nodded slowly.

“I’ve given a few talks,” he continued. “Leadership seminars. Ethics conferences. They always want stories about decisive action in combat. Heroic charges. The usual mythology. Sometimes I give them those. But more and more, I find myself talking about a confrontation in a mess hall instead.”

She raised an eyebrow. “Is that so?”

“I tell them about a general who thought he understood responsibility,” he said, “until a corporal reminded him that responsibility isn’t permission to ignore facts. That conscience doesn’t move up the chain like a requisition form. That sometimes the lowest-ranking person in the room is the one who best understands the risk.”

He smiled faintly.

“They tend to remember that story better,” he said. “Maybe because they can imagine themselves as the corporal, not the general.”

“Do you regret it?” she asked softly. “That day. The way you reacted.”

His eyes darkened. “Every day,” he said. “Not because of how it ended—that, I’m grateful for—but because it revealed something about me I didn’t want to see. That I’d started to treat obedience as the primary virtue, instead of one tool among many. You cracked that open.”

“Better late than never,” she said.

“Better never than too late,” he countered, then shook his head. “Either way, I’m glad you stood your ground.”

They sat in comfortable silence for a moment, the clink of cutlery and murmur of conversation filling the space between them.

One of the younger vets leaned over to her friend and whispered, just loud enough to carry, “That’s him, isn’t it? The general.”

“Shut up and eat your pie,” the friend hissed back, eyes wide.

Morgan’s lips twitched.

“Seems our little story traveled,” he said.

“Stories do that,” she replied. “Especially the ones that scare and comfort people at the same time.”

He finished his coffee and set the cup down with a decisive little tap.

“You know,” he said, “I used to think courage was a scarce resource. Something you rationed for the big moments. Now I think it’s more like seasoning. Something you sprinkle into the small choices every day, so that when the big moment comes, it doesn’t taste so strange.”

“You and your metaphors,” she teased. “Careful, you’re going to end up on a poster.”

He stood, reaching for his wallet.

“Put this on my tab,” he said.

“You don’t have a tab,” she replied.

“Start one,” he said. “I have a feeling I’ll be back.”

As he turned to go, he paused.

“Thank you, Elena,” he said. “For that day. For this one. For proving that a cook’s courage can change more than a menu.”

“Take care, Daniel,” she said. “And remember: if the meat smells off, walk away.”

He laughed aloud, genuine and unguarded, then stepped out into the afternoon light.

The door closed behind him, the bell jingling.

The younger vet at the counter shook her head in disbelief.

“You know,” she said, “if someone wrote a movie about you two, people would say it was unrealistic.”

“That’s how you know it’s true,” Elena said, reaching for the coffee pot again.

The day went on. Orders came in. Plates went out. A kid spilled his milk and cried, and she knelt to mop it up and hand him a fresh glass. The grill sizzled. The dishwasher hummed. The old sergeant major at the corner table grumbled about the sports section.

As the sun dipped low and the last customers drifted out, she wiped down the counter and flipped the sign on the door to Closed. She stood for a moment in the warm quiet, listening to the familiar creaks and clicks.

In the reflection of the front window, she saw herself—older, steadier, apron dusted with flour. The medal in the back office, the plaque above the counter, the invisible line that connected a mess hall in Kandahar to this small diner.

War had taught her many things. That fear was constant. That luck was fickle. That bureaucracy was as real a battlefield as any.

But most of all, it had taught her that integrity was not a grand gesture reserved for rare days. It was a posture. A way of standing in the world. A decision, repeated over and over, to serve what was right even when it cost you.

She turned off the lights, one by one, until only the glow from the sign outside remained, casting the words on the plaque into soft shadow.

Sometimes, the bravest act in uniform is saying no.

Sometimes, the bravest act out of uniform is living as if that no still matters.

She locked the door, pocketed the keys, and stepped out into the night—just a woman who once was “just the cook,” walking toward tomorrow with the quiet courage of someone who had already refused the worst thing she could imagine: betraying her own conscience.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Fake HOA Cop Tries To Undress My Visitor — Stunned When She Turns Out To Be a Detective.

Fake HOA Cop Tries To Undress My Visitor — Stunned When She Turns Out To Be a Detective Part…

They Ripped Her Insignia Before 5,000 Sailors — Until a Phantom Sub Surfaced for Her Alone

They Ripped Her Insignia Before 5,000 Sailors — Until a Phantom Sub Surfaced for Her Alone Part 1 They…

Commander Beats A Female Soldier At Drill Practise 5 Seconds Later,She Destroys Him In Front Of Everyone

Commander Beats A Female Soldier At Drill Practise 5 Seconds Later, She Destroys Him In Front Of Everyone Part…

Racist Commander Threw the New Female Soldier Into Mud — Then She Showed Them Her Real Power

Racist Commander Threw the New Female Soldier Into Mud — Then She Showed Them Her Real Power. The moment everyone…

She Refused to Charge Freezing Soldiers – The Next Morning, the Army Shut Down Her Street!

She Refused to Charge Freezing Soldiers – The Next Morning, the Army Shut Down Her Street! Part 1 The…

Stepmom Made Me Sleep in the Garage for 4 Years—Then Tried to Steal My “Dead” Dad’s Estate

Stepmom Made Me Sleep in the Garage for 4 Years—Then Tried to Steal My “Dead” Dad’s Estate Part 1 …

End of content

No more pages to load